Yevgenia Bosch on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

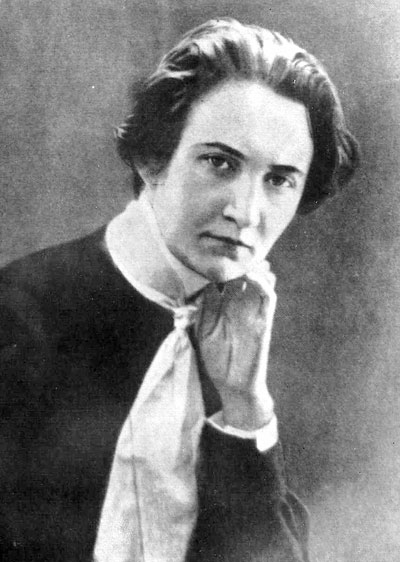

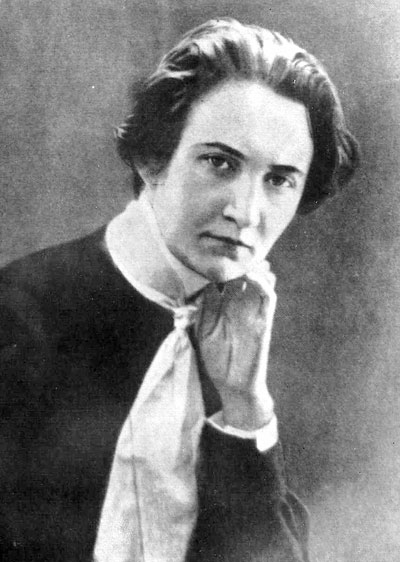

Yevgenia Bogdanovna; russian: Го́тлибовна) Bosch; russian: Евге́ния Богда́новна Бош; german: Jewgenija Bogdanowna Bosch ( née Meisch ; – 5 January 1925) was a Ukrainian Bolshevik revolutionary, politician, and member of the Soviet government in Ukraine during the revolutionary period in the early 20th century.

Yevgenia Bosch is sometimes considered the first modern woman leader of a national government, having been Minister of Interior and the Acting Leader of the provisional Soviet government of Ukraine in 1917. For that reason she is also sometimes considered the first Prime Minister of independent Ukraine.

Bosch had a growing interest in radical politics. She had limited involvement with the Social Democrats. In 1901, at 22, she became a member of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) and after the II Party Congress joined the

Bosch had a growing interest in radical politics. She had limited involvement with the Social Democrats. In 1901, at 22, she became a member of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) and after the II Party Congress joined the

Biography of Bosch

Ukrayinska Pravda {{DEFAULTSORT:Bosch, Yevgenia 1879 births 1925 suicides People from Ochakiv People from Odessky Uyezd People from the Russian Empire of German descent Ukrainian people of German descent Ukrainian people of Moldovan descent Soviet women in politics 20th-century Ukrainian women politicians Russian Social Democratic Labour Party members Old Bolsheviks Russian Constituent Assembly members Lithuanian–Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic people Soviet interior ministers of Ukraine Soviet people of the Ukrainian–Soviet War Ukrainian exiles in the Russian Empire Expatriates from the Russian Empire in Switzerland Suicides by firearm in the Soviet Union Politicians who committed suicide Soviet politicians who committed suicide Women in war Female revolutionaries

Early life and family

Officially, Bosch was born in Adjigiol village near Ochakiv, in the Kherson Governorate of theRussian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the List of Russian monarchs, Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended th ...

, but some records report that she was born in Ochakiv, Kherson Governorate in a family of a German colonist, mechanic, and landowner Gotlieb Meisch and Bessarabian noblewoman Maria Krusser. Yevgenia Bosch was the fifth and the youngest child in the family. Soon after the death of Gotlieb Meisch, Maria Krusser married her husband's brother, Theodore Meisch.

For three years, Yevgenia attended Voznesensk Female Gymnasium, after which, due to her health condition, she worked for her stepfather as a secretary. Being stuck in her parents' household Yevgenia sought means to leave. Her older brother Oleksiy acquainted her with his friend Peter Bosch, who was an owner of a local small wagon shop. At 16, Yevgenia married Bosch, and later gave birth to two daughters.

According to another source, Yevgenia Bosch was born in Ukraine to Gottlieb Meisch, an ethnic German immigrant from Luxembourg

Luxembourg ( ; lb, Lëtzebuerg ; french: link=no, Luxembourg; german: link=no, Luxemburg), officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, ; french: link=no, Grand-Duché de Luxembourg ; german: link=no, Großherzogtum Luxemburg is a small land ...

, and his Moldavian wife. Bosch's parents quarrelled often and her childhood was reportedly an unhappy one. She was educated at the Voznesensk women's gymnasium. At age 17, her parents attempted to arrange her marriage to an older man, but she rebelled and married a bourgeois businessman named Peter Bosch. They had two children.

Radical politics

Bosch had a growing interest in radical politics. She had limited involvement with the Social Democrats. In 1901, at 22, she became a member of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) and after the II Party Congress joined the

Bosch had a growing interest in radical politics. She had limited involvement with the Social Democrats. In 1901, at 22, she became a member of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) and after the II Party Congress joined the Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

faction in 1903. She tried to educate herself while raising her two daughters.

In the meantime, her younger sister, Elena Rozmirovich

Elena Fedorovna Rozmirovich-Troyanovskaya (russian: Елена Федоровна Розмирович, 10 March 1886 – 30 August 1953) was a Russian revolutionary and politician and later an official in the Soviet Union. In 1917 she was one of ...

, was a dedicated revolutionary. The Bosch house was searched by the police for illegal political literature in 1906. The police search was unsuccessful, but Bosch left her husband and fled to Kyiv, where she joined the revolutionary underground. In 1907, she divorced her husband and moved to Kyiv

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the List of European cities by populat ...

where Bosch lived at vulytsia Velyka Pidvalna, 25 (today vulytsia Yaroslaviv Val).

In Kyiv, she established contact with the local Bolshevik faction, and together with her younger sister Elena Rozmirovich (future wife of Nikolai Krylenko, chekist), conducted underground revolutionary activities. Much of the Kyiv group was arrested and exiled in 1910, but Bosch remained in Kyiv and found a lover and revolutionary partner in Georgy Pyatakov. Bosch was head of the Kyiv Committee of the Russian Social Democratic Worker's Party (RSDRP). Bosch and Pyatakov led the Kyiv committee until their arrest and exile to Irkutsk Governorate Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part o ...

in 1912. During her imprisonment, she fell ill with tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in w ...

.

Alongside Pyatakov, Bosch managed to escape from Kachuga volost (Upper-Lena uyezd, Irkutsk Governorate), first to Vladivostok

Vladivostok ( rus, Владивосто́к, a=Владивосток.ogg, p=vɫədʲɪvɐˈstok) is the largest city and the administrative center of Primorsky Krai, Russia. The city is located around the Zolotoy Rog, Golden Horn Bay on the Sea ...

, and then, with a short stint in Japan, to the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., federal district, five ma ...

.

Afterwards, Bosch and Pyatakov made their way to Switzerland where an émigré group of revolutionaries was active. Bosch accepted Lenin's invitation and attended the conference of Russian revolutionaries in Bern in 1915 (the ''Bern conference''). She was initially opposed to Lenin's desire to urge the proletariat towards revolution. Still in Switzerland, together with Georgy Pyatakov they established the so-called ''Baugy group'' (Baugy is a suburb of Lausanne

Lausanne ( , , , ) ; it, Losanna; rm, Losanna. is the capital and largest city of the Swiss French speaking canton of Vaud. It is a hilly city situated on the shores of Lake Geneva, about halfway between the Jura Mountains and the Alps, and fac ...

), which included Nikolai Bukharin

Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin (russian: Никола́й Ива́нович Буха́рин) ( – 15 March 1938) was a Bolshevik revolutionary, Soviet politician, Marxist philosopher and economist and prolific author on revolutionary theory. ...

, Nikolai Krylenko and others, and stood in opposition to Lenin concerning the nationalities factor. Her newspaper ''Social Democratic Voice'' argued:

Afterwards she lived for some time with Pyatakov in Stockholm, Sweden, and in Oslo

Oslo ( , , or ; sma, Oslove) is the capital and most populous city of Norway. It constitutes both a county and a municipality. The municipality of Oslo had a population of in 2022, while the city's greater urban area had a population of ...

, Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and t ...

(then called Christiania).

After the February Revolution, Bosch and Pyatakov were among the first Bolshevik emigres to return to Petrograd. She moved soon afterwards to Kyiv, where she was elected chairman of the party committee for the Southwestern region. She then returned to what was then the Russian Republic, originally aiming at organizing an opposition to Lenin. After the April conference of the RSDLP, Bosch came to change her position, adhering to Lenin's ideas. Her reconciliation with Lenin cost her her marriage. She was elected chairman of a district (okrug) Party Committee and then of a provincial (oblast) Party Committee in the Southwestern Krai.

Declaration of Soviet Ukraine

Bosch was instrumental in launching the First All-Ukrainian Congress of Soviets (December 11–12, 1917, Kharkiv). At this Congress, the Ukrainian People's Republic was proclaimed to be the Soviet Republic, and its membership in a federation with Soviet Russia was also declared. She was elected to the People's Secretariat of the Bolshevik government of Ukraine. The Congress also denounced the Central Council of Ukraine, also known as the Central Rada, as well as its laws and instructions. The decrees of the Petrograd Council of People's Commissars extended to Ukraine and an official alliance with the Russia Red Army was declared. Bosch became Minister of the Interior when the Bolsheviks took control of the government in January 1918. As Soviet Ukraine's first Minister of the Interior and Head of the Secret Police, Evgenia Bosch was effectively head of the government, responsible for taking direct charge of the Soviet fight against the bourgeois business owners' and landlords' counter-revolution.Opposition to the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

In March, Bosch was outraged when the Soviets signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with Germany, which gave control of territories in western Ukraine to Germany. She resigned her government post in protest and organised worker battalions to resist the advance of the German army through Ukraine. She enlisted, along with Pyatakov and her daughter Maria, in the Red Army forces led by Vladimir Antonov-Ovseyenko. She became ill with tuberculosis and heart disease, however, and after several months of recuperation, she left Ukraine for Russia, where she filled political and military administrative posts for the next few years as the civil war continued. In August 1918, she was the chairwoman of the Penza Governorate Party Committee during the controversy that led to the issue of the so-called Lenin's Hanging Order. She was then posted to the Caspian-Caucasus front, and later to Astrakhan. In 1919, she was a member of the committee for the defence of Lithuania and Belarus, and then served as a political commissar for the war againstGeneral Denikin

Anton Ivanovich Denikin (russian: Анто́н Ива́нович Дени́кин, link= ; 16 December Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_December.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New St ...

. Throughout this civil war period, she is reputed to have slept with a revolver under her pillow.

During the period after November 1919 she was under treatment for her tuberculosis and related ailments. She occasionally held secondary positions in the Central Committee of the All-Russian Union of Land and Forest Workers, the People's Commissariat of Education, the Central Union Commission and the People's Commissariat of Food for the provision of aid to the starving, and the People's Commissariat of Workers' and Peasants' Inspection and wrote her memoirs. In 1920–22, she chaired the Military Historical Commission, but from 1922, she was incapacitated by severe illness.

Trotskyism, death and legacy

Bosch joined the Left Opposition in 1923. She was harshly critical of the “bureaucratic group” she saw controlling the Soviet government. She was a supporter of Leon Trotsky and signed The Declaration of 46, the first official statement by the opposition toJoseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

.

Bosch fell out of favour with the Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

-Nikolai Bukharin

Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin (russian: Никола́й Ива́нович Буха́рин) ( – 15 March 1938) was a Bolshevik revolutionary, Soviet politician, Marxist philosopher and economist and prolific author on revolutionary theory. ...

leadership. In 1924, she succumbed to despair after hearing that Trotsky had been forced to resign as leader of the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

, as well as in pain from her heart condition and tuberculosis; she died by suicide by self-inflicted gunshot in January 1925.

Her suicide was met with an immediate, deliberate effort by the Soviet government to suppress official acknowledgement of her status as a major Bolshevik leader.

Her memoirs, ''A Year of Struggle'', were published posthumously in 1925.

A large suspension bridge over the Dnieper

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine ...

in Kyiv

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the List of European cities by populat ...

was named in Bosch's honour when it was raised in 1925. Yevgeniya Bosch Bridge, which existed in Kyiv from 1925 to 1941, was named after her. The bridge was constructed by Evgeny Paton on the base of the remnants of Nicholas Chain Bridge

The Nicholas Chain Bridge (or Nikolaevsky Chain Bridge; uk, Миколаївський ланцюговий міст; russian: Николаевский цепной мост) was a chain bridge over the Dnieper that existed from 1855 to 1920 in ...

blown up by retreating Polish troops in 1920. The bridge was destroyed during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. The site of the Bosch bridge is now the location of the Metro Bridge.

A number of other important objects in Ukraine and other places in the Soviet Union were given her name, most of which were renamed after 1991 and particularly since 2015, when communist monuments, communist street names and other toponyms have been outlawed in Ukraine under decommunization laws.

Her daughter Olha married Yuriy Kotsyubynsky

Yuriy Mykhailovych Kotsiubynsky ( uk, Юрій Михайлович Коцюбинський) (December 7, 1896 – March 8, 1937) was a Bolshevik politician, activist, member of the Soviet government in Ukraine, one of the co-founders of Re ...

and gave birth to Oleh Yuriyovych Kotsyubynsky.

See also

* Rosalia ZemlyachkaNotes

References

Bibliography

* Bosch, Evgenia. The National Government and Soviet Power in Ukraine (1919) * Bosch, Evgenia. "October days in the Kyiv region" ''Proletarian revolution'' No. 11. pp. 52–67 (1923) * Bosch, Evgenia. "Regional Party Committee of the S.-D (B-Kov) of the South-Western Region" ''Proletarian revolution'' No. 5. pp. 128-149 (1924) * Bosch, Evgenia. "Meetings and conversations with Vladimir Ilyich (1915-1918)" ''Proletarian revolution'' No. 3. pp. 155-173 (1924) * Bosch, Evgenia. ''A Year of Struggle: The Struggle for the Régime in the Ukraine from April 1917 to the German Occupation'' (''God Borby: Borba Za Vlast Na Ukraine'') (Moscow) 1925, republished 1990. *External links

Biography of Bosch

Ukrayinska Pravda {{DEFAULTSORT:Bosch, Yevgenia 1879 births 1925 suicides People from Ochakiv People from Odessky Uyezd People from the Russian Empire of German descent Ukrainian people of German descent Ukrainian people of Moldovan descent Soviet women in politics 20th-century Ukrainian women politicians Russian Social Democratic Labour Party members Old Bolsheviks Russian Constituent Assembly members Lithuanian–Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic people Soviet interior ministers of Ukraine Soviet people of the Ukrainian–Soviet War Ukrainian exiles in the Russian Empire Expatriates from the Russian Empire in Switzerland Suicides by firearm in the Soviet Union Politicians who committed suicide Soviet politicians who committed suicide Women in war Female revolutionaries