Yates Stirling, Jr. on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Yates Stirling Jr. (April 30, 1872 ŌĆō January 27, 1948) was a decorated and controversial

Yates Stirling Jr. was born in

Yates Stirling Jr. was born in  When Stirling was nearly fifteen, his father was given command of the old

When Stirling was nearly fifteen, his father was given command of the old  During the three-month, first-class training cruise on the pre-

During the three-month, first-class training cruise on the pre-

rear admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star "admiral" rank. It is often regarde ...

in the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

whose 44-year career spanned from several years before the SpanishŌĆōAmerican War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

to the mid-1930s. He was awarded the Navy Cross

The Navy Cross is the United States Navy and United States Marine Corps' second-highest military decoration awarded for sailors and marines who distinguish themselves for extraordinary heroism in combat with an armed enemy force. The medal is eq ...

and French Legion of Honor

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la L├®gion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon B ...

for distinguished service during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. The elder son of Rear Admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star "admiral" rank. It is often regarde ...

Yates Stirling, he was an outspoken advocate of American sea power as a strong deterrent to war and to protect and promote international commerce. During Stirling's naval career and following retirement, he was a frequent lecturer, newspaper columnist and author of numerous books and articles, including his memoirs, ''Sea Duty: The Memoirs of a Fighting Admiral'', published in 1939. Describing himself, Stirling wrote, "All my life I have been called a stormy petrel. I have never hesitated to use the pen to reveal what I considered should be brought to public attention, usually within the Navy, but often to a wider public. I seem to see some benefits that have come through those efforts. I have always believed that a naval man is disloyal to his country if he does not reveal acts that are doing harm to his service and show, if he can, how to remedy the fault. An efficient Navy cannot be run with 'yes men' only."The New York Times, ''Yates Stirling Jr., Navy Veteran, Dies'' January 28, 1948. p. 23

Early life and education

Yates Stirling Jr. was born in

Yates Stirling Jr. was born in Vallejo, California

Vallejo ( ; ) is a city in Solano County, California and the second largest city in the North Bay region of the Bay Area. Located on the shores of San Pablo Bay, the city had a population of 126,090 at the 2020 census. Vallejo is home to the ...

, in 1872 to Lieutenant Commander

Lieutenant commander (also hyphenated lieutenant-commander and abbreviated Lt Cdr, LtCdr. or LCDR) is a commissioned officer rank in many navies. The rank is superior to a lieutenant and subordinate to a commander. The corresponding rank i ...

Yates Stirling Sr. (1843ŌĆō1929) (United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (US Naval Academy, USNA, or Navy) is a federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as Secretary of the Navy. The Naval Academy ...

Class of 1863) and his wife, Ellen Salisbury (n├®e Hale) Stirling. At the time of Yates Jr.'s birth, his father was assigned to the , receiving ship

A hulk is a ship that is afloat, but incapable of going to sea. Hulk may be used to describe a ship that has been launched but not completed, an abandoned wreck or shell, or to refer to an old ship that has had its rigging or internal equipmen ...

at Mare Island Naval Shipyard

The Mare Island Naval Shipyard (MINSY) was the first United States Navy base established on the Pacific Ocean. It is located northeast of San Francisco in Vallejo, California. The Napa River goes through the Mare Island Strait and separates th ...

. From an established Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

family, Stirling was a great-grandson of Thomas Yates (1740ŌĆō1815), captain, Fourth Battalion, Maryland Regulars during the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 ŌĆō September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

. When he was about four, Stirling's family moved to Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

, Maryland, the home of his father and grandfather. He was one of five children that survived to adulthood and the oldest of two boys, both of whom followed their father's footsteps to the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis

Annapolis ( ) is the capital city of the U.S. state of Maryland and the county seat of, and only incorporated city in, Anne Arundel County. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east o ...

. His younger brother, Commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countries this naval rank is termed frigate captain.

...

Archibald G. Stirling (1884ŌĆō1963) (United States Naval Academy Class of 1906) retired in 1933 but returned to active duty from 1942 to 1945 during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countriesŌĆöincluding all of the great powersŌĆöforming two opposin ...

. The Yates Stirling family was the second in U.S. Naval history to have father and son flag officers (rear admirals) living at the same time. The first were Rear Admirals Thomas O. Selfridge Sr. and Jr.

As a boy living in Baltimore's upper west side, Stirling attended public schools where, despite a professed dislike of physical combat, he had a reputation of being a fighter. While his father was at sea for as long as three years at a time, Stirling had a happy home life with a mother that instilled a love for reading and provided private teachers that enabled him to skip grades at school, though Stirling admitted he was not a good student. During his father's cruise absences, the family's only knowledge of his well-being came in bulky packets of letters arriving in bunches over long intervals that Stirling's mother, Ellen, would read aloud to her children. The exciting details of life on a warshipŌĆö"gales, tropical coral reefs, savage people, hunting, and yellow fever"ŌĆöinfluenced Stirling's desire for the naval life. But he saw that it was not without sacrifice. A younger brother was about three when Stirling's father left Baltimore for a long cruise. A few months later, the boy contracted diphtheria and died. Another younger brother, Archie, was born shortly after that. Yates Stirling Jr. wondered how his father must have felt when he returned home and saw a new son that was nearly the same age as the one he had lost.

When Stirling was nearly fifteen, his father was given command of the old

When Stirling was nearly fifteen, his father was given command of the old sloop-of-war

In the 18th century and most of the 19th, a sloop-of-war in the Royal Navy was a warship with a single gun deck that carried up to eighteen guns. The rating system covered all vessels with 20 guns and above; thus, the term ''sloop-of-war'' enc ...

, the receiving ship at the Washington Navy Yard

The Washington Navy Yard (WNY) is the former shipyard and ordnance plant of the United States Navy in Southeast Washington, D.C. It is the oldest shore establishment of the U.S. Navy.

The Yard currently serves as a ceremonial and administrativ ...

. CDR Stirling moved his family from Baltimore to Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, where the family set up comfortable, but cramped living quarters on the ''Dale''. Stirling was delighted with the change, and when he wasn't at school, enjoyed sailing on the Anacostia

Anacostia is a historic neighborhood in Southeast Washington, D.C. Its downtown is located at the intersection of Good Hope Road and Martin Luther King Jr. Avenue. It is located east of the Anacostia River, after which the neighborhood is na ...

and Potomac River

The Potomac River () drains the Mid-Atlantic United States, flowing from the Potomac Highlands into Chesapeake Bay. It is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map. Retrieved Augus ...

s in a boat that the ''Dale's'' sailors had rigged for him. Thrown in with the sons of naval officers at the Navy Yard, he soon realized that like himself, most aspired to naval careers. When Yates Jr. was fifteen, his father had taken him to the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

for the purpose of meeting President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966ŌĆō2010 Japanese ful ...

Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

and requesting an appointment to Annapolis for his son. Dressed in shorts, that Stirling later regretted wearing since they accentuated his youthful looks, he recalled Cleveland telling his father, "Why, Commander, your son looks too young to go to Annapolis this year. Maybe next, it will be possible. Shall I have his name put down for an appointment then?"Stirling, p. 8

Although a Marylander, Stirling secured his appointment to the Naval Academy the following year from William Whiting, congressman from Massachusetts's 11th congressional district

Massachusetts's 11th congressional district is an obsolete congressional district in eastern Massachusetts. It was eliminated in 1993 after the 1990 U.S. census. Its last congressman was Brian Donnelly; its most notable were John Quincy Adams ...

. Whiting was a family friend and Stirling's frequent ice-skating companion on the Potomac. Since no one from Whiting's district had sought an appointment that year, it could be filled by the Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the se ...

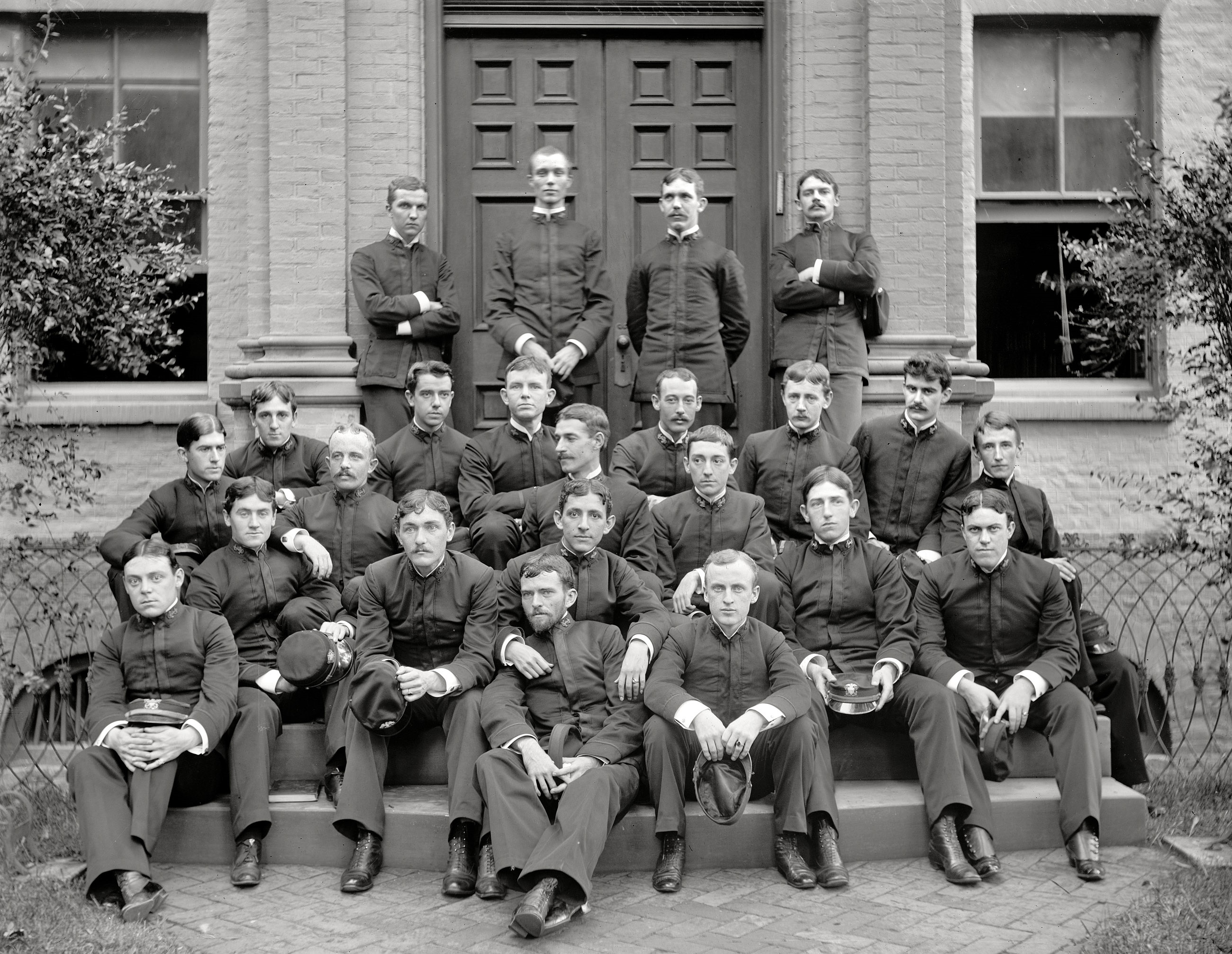

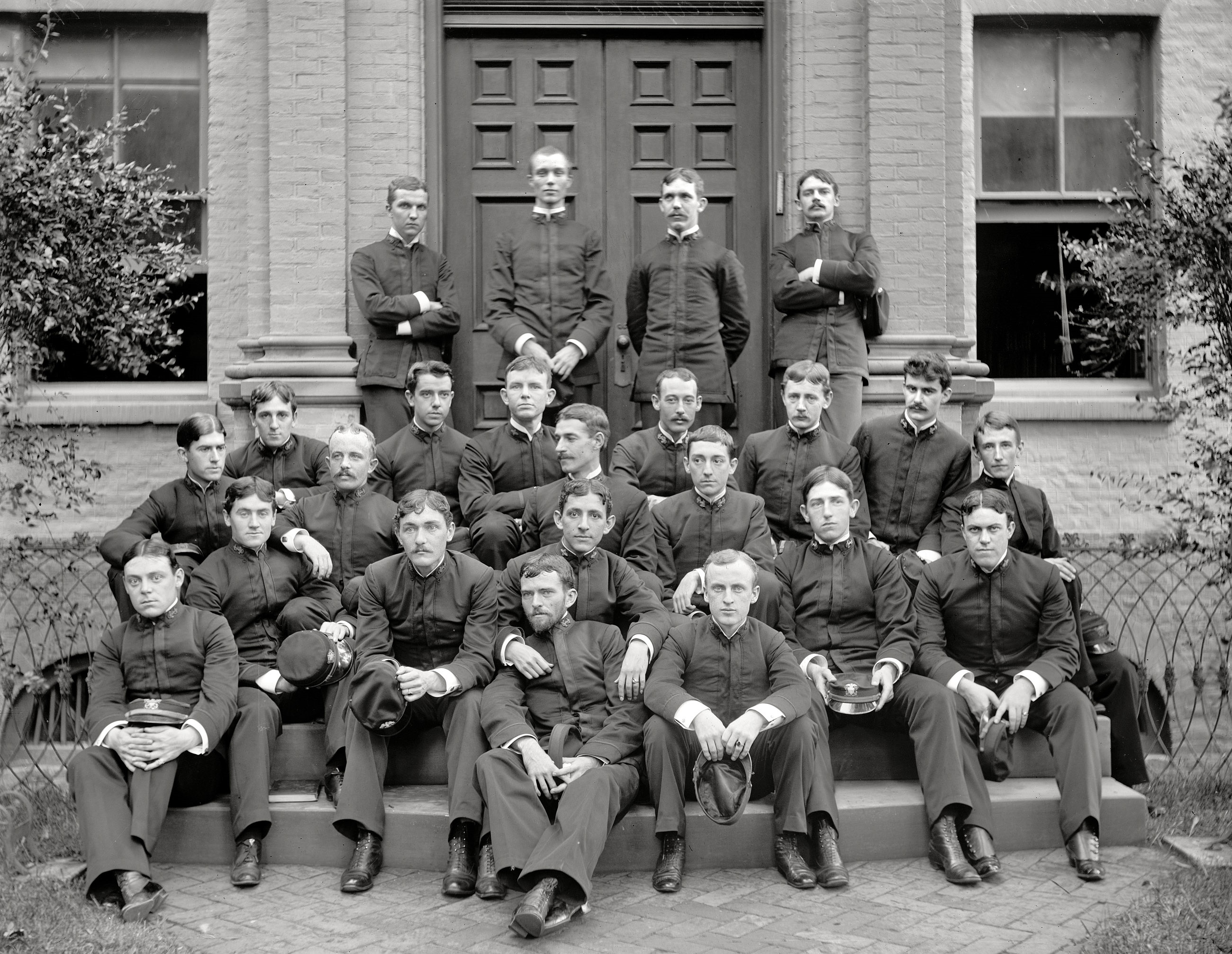

at the Congressman's request. Whiting wrote the Secretary and it was done. Stirling reported for examinations that he passed and entered Annapolis on September 6, 1888. Naval Cadet Stirling continued his less than stellar academic endeavors at Annapolis. "I lacked fundamental grounding in the various basic subjects, but, even worse, I had not formed the habit of close application and was much keener for games and pranks than for my studies. At times, however, things seemed easy enough, showing that after all my brain was sound but that it needed much disciplining."

During the three-month, first-class training cruise on the pre-

During the three-month, first-class training cruise on the pre-Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

sloop-of-war , before beginning his final academic year, Stirling and another cadet were ordered aloft during a severe squall

A squall is a sudden, sharp increase in wind speed lasting minutes, as opposed to a wind gust, which lasts for only seconds. They are usually associated with active weather, such as rain showers, thunderstorms, or heavy snow. Squalls refer to the ...

to shorten sail and send down the topgallant and royal sail

A royal is a small sail flown immediately above the topgallant on square rigged sailing ships. It was originally called the "topgallant royal" and was used in light and favorable winds.

Royal sails were normally found only on larger ships with m ...

yards

The yard (symbol: yd) is an English unit of length in both the British imperial and US customary systems of measurement equalling 3 feet or 36 inches. Since 1959 it has been by international agreement standardized as exactly 0.914 ...

. " ueezing out tar on every handhold to prevent being blown out into space by the great force of the wind and the pressure of the solid sheets of rain", Stirling climbed up two vertical shrouds

Shroud usually refers to an item, such as a cloth, that covers or protects some other object. The term is most often used in reference to '' burial sheets'', mound shroud, grave clothes, winding-cloths or winding-sheets, such as the famous S ...

and Jacob's ladders to the top gallant yard, 120 feet above the deck. Succeeding in furling the sails and lowering the yards by "exerting every ounce of strength we could muster and while the gale was at its height", Stirling wrote in his memoirs forty years later, "The physical condition and the confidence acquired that enable you to hang, without batting an eye, by one hand in space with a yawning drop below you are things the modern sailor never attains. That sense of exaltation was well worth the price paid." Having been in the bottom third of his class during the first three years at Annapolis, in his final year of studies, Stirling found the courses more practical to the knowledge and skill he would need as a naval officer. Applying himself to ensure his standing would be high enough to be offered a commission, he improved his academic ranking that year and graduated from the United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (US Naval Academy, USNA, or Navy) is a federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as Secretary of the Navy. The Naval Academy ...

on June 3, 1892, twenty-second in a class of forty.

Naval career

Early years

During the two years at sea then required of a naval cadet that had passed his academic studies before commissioning as anensign

An ensign is the national flag flown on a vessel to indicate nationality. The ensign is the largest flag, generally flown at the stern (rear) of the ship while in port. The naval ensign (also known as war ensign), used on warships, may be diffe ...

, Stirling was first assigned to the protected cruiser

Protected cruisers, a type of naval cruiser of the late-19th century, gained their description because an armoured deck offered protection for vital machine-spaces from fragments caused by shells exploding above them. Protected cruisers re ...

that he and four other cadets joined in the Sandwich Islands

The Hawaiian Islands ( haw, N─ü Mokupuni o HawaiŌĆśi) are an archipelago of eight major islands, several atolls, and numerous smaller islets in the North Pacific Ocean, extending some from the island of Hawaii in the south to northernmost Kur ...

, (as the Territory of Hawaii

The Territory of Hawaii or Hawaii Territory ( Hawaiian: ''Panalāʻau o Hawaiʻi'') was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from April 30, 1900, until August 21, 1959, when most of its territory, excluding ...

was also known) in July 1892. Seeing these exotic islands that he had heard about in his father's stories, despite the tropical setting Stirling was somewhat disappointed to find no "truly Hawaiian villages" and that "Hawaiian life even then had merged into Western civilization or Oriental."Stirling, p. 17 Observing the miscegenation

Miscegenation ( ) is the interbreeding of people who are considered to be members of different races. The word, now usually considered pejorative, is derived from a combination of the Latin terms ''miscere'' ("to mix") and ''genus'' ("race") ...

of whites with the indigenous

Indigenous may refer to:

*Indigenous peoples

*Indigenous (ecology), presence in a region as the result of only natural processes, with no human intervention

*Indigenous (band), an American blues-rock band

*Indigenous (horse), a Hong Kong racehorse ...

Hawaiians during the few weeks his ship was at Hawaii, he later wrote in his memoirs, "I found them most wholesome companions, although I had the feeling that I must be careful not to fall in love. It seemed strange to see a dignified white official surrounded by children with skins as dark as a mulatto." Stirling's nineteenth century ethnic and cultural beliefs aside, he noted the geopolitical

Geopolitics (from Greek ╬│ß┐å ''g├¬'' "earth, land" and ŽĆ╬┐╬╗╬╣Žä╬╣╬║╬« ''politikßĖŚ'' "politics") is the study of the effects of Earth's geography (human and physical) on politics and international relations. While geopolitics usually refers to ...

undercurrents of the importance of Hawaii to the United States, Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

and Japan

Japan ( ja, µŚźµ£¼, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

as each maintained a naval presence. "All three nations were watching each other to be sure no one would obtain advantage over another and become too powerful in Court circles. Hawaii was known to be an important strategical location with great commercial prospects. The United States would not have permitted any other nation to seize the Islands, yet at that time, the Administration in Washington, under President Cleveland, did not feel itself strong enough to take them for this country. Our method, therefore, was one of watchful waiting and maintaining friendly relations with the Hawaiian Queen ( Liliuokalani) and her government."Stirling, p. 18 Japan's long-standing ambitions in the Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

were driving a naval buildup for the First Sino-Japanese War

The First Sino-Japanese War (25 July 1894 ŌĆō 17 April 1895) was a conflict between China and Japan primarily over influence in Korea. After more than six months of unbroken successes by Japanese land and naval forces and the loss of the po ...

two years later and eventually for war with the U.S., as Stirling would predict in articles and lectures in the 1930s and as others such as Homer Lea

Homer Lea (November 17, 1876 ŌĆō November 1, 1912) was an American adventurer, author and geopolitical strategist. He is today best known for his involvement with Chinese reform and revolutionary movements in the early twentieth century and as ...

, had foretold as early as the first decade of the twentieth century.

''San Francisco'' was relieved of duty in Hawaii in mid-August 1892 and set out for repairs at Mare Island. Following repairs, Stirling's ship joined a squadron of two other cruisers, , and a gunboat

A gunboat is a naval watercraft designed for the express purpose of carrying one or more guns to bombard coastal targets, as opposed to those military craft designed for naval warfare, or for ferrying troops or supplies.

History Pre-steam ...

, bound for a large naval review

A fleet review or naval review is an event where a gathering of ships from a particular navy is paraded and reviewed by an incumbent head of state and/or other official civilian and military dignitaries. A number of national navies continue to ...

at New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

as part of the following year's (1893) Chicago World's Fair. At Acapulco Bay, Mexico, "celebrated for its manŌĆæeating sharks", Stirling was visiting ''Charleston'' and accepted the challenge of the Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

chaplain

A chaplain is, traditionally, a cleric (such as a Minister (Christianity), minister, priest, pastor, rabbi, purohit, or imam), or a laity, lay representative of a religious tradition, attached to a secularity, secular institution (such as a hosp ...

, Father William H. Reaney, to swim off the anchored ship. "We donned our bathing trunks. The chaplain dove first off the gangway, and I followed him. When I struck the water, all the ghastly stories I had ever heard of sharks came into my mind. I swam swiftly back to the gangway, getting there just as (chaplain) Rainnie (sic) reached it. He said, breathlessly: 'I don't think we should put too much confidence in the Lord's being able to protect us from our own stupidity. Back aboard, the officer of the deck pointed out several black fins where Stirling had been swimming moments earlier. During the voyage around South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the southe ...

and through the Straits of Magellan

The Strait of Magellan (), also called the Straits of Magellan, is a navigable sea route in southern Chile separating mainland South America to the north and Tierra del Fuego to the south. The strait is considered the most important natural pass ...

, the ship made ports of call at Callao, Peru

Callao () is a Peruvian seaside city and region on the Pacific Ocean in the Lima metropolitan area. Callao is Peru's chief seaport and home to its main airport, Jorge Ch├Īvez International Airport. Callao municipality consists of the whole C ...

, Valparaiso, Chile and Montevideo, Uruguay

Montevideo () is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Uruguay, largest city of Uruguay. According to the 2011 census, the city proper has a population of 1,319,108 (about one-third of the country's total population) in an area of . M ...

to show the flag

{{Short pages monitor

In 1914, Stirling assumed command of Submarine Flotilla, Atlantic Fleet, attached successively to the and . In April 1914, he led a flotilla of torpedo boats into Mexican waters off Vera Cruz during the

In 1914, Stirling assumed command of Submarine Flotilla, Atlantic Fleet, attached successively to the and . In April 1914, he led a flotilla of torpedo boats into Mexican waters off Vera Cruz during the

Sterling relieved RADM Henry H. Hough, as commander of the

Sterling relieved RADM Henry H. Hough, as commander of the

Stirling married the former Adelaide Egbert, daughter of

Stirling married the former Adelaide Egbert, daughter of ''The San Francisco Call'', May 25, 1899

/ref>

Aubin, J. Harris (1906) ''Register of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion'', Boston, Press of Edwin L. Slocomb.

Hamersly, Lewis Randolph. (1902). ''The Records of Living Officers of the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps, Seventh Edition'', New York: L. R. Hamersly Company.

* Ō

online, complete

* Ō¢

online, partial

* Ō¢

* * Ō¢

online, partial

Arlington National Cemetery

{{DEFAULTSORT:Stirling, Yates Jr. 1872 births 1948 deaths United States Naval Academy alumni Naval War College alumni United States Navy admirals United States submarine commanders American military personnel of the SpanishŌĆōAmerican War American military personnel of the PhilippineŌĆōAmerican War United States Navy personnel of World War I Recipients of the Navy Cross (United States) Officiers of the L├®gion d'honneur Burials at Arlington National Cemetery Military personnel from Vallejo, California Recipients of the Order of the Crown (Italy)

Manila

Manila ( , ; fil, Maynila, ), officially the City of Manila ( fil, Lungsod ng Maynila, ), is the capital of the Philippines, and its second-most populous city. It is highly urbanized and, as of 2019, was the world's most densely populate ...

, Philippines; Yokohama

is the second-largest city in Japan by population and the most populous municipality of Japan. It is the capital city and the most populous city in Kanagawa Prefecture, with a 2020 population of 3.8 million. It lies on Tokyo Bay, south of To ...

, Japan; Colombo

Colombo ( ; si, ÓČÜÓĘ£ÓĘģÓČ╣, translit=KoßĖĘam╠åba, ; ta, Ó«ĢÓ»ŖÓ«┤Ó»üÓ««Ó»ŹÓ«¬Ó»ü, translit=KoßĖ╗umpu, ) is the executive and judicial capital and largest city of Sri Lanka by population. According to the Brookings Institution, Colombo me ...

, Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ÓĘüÓĘŖÓČ╗ÓĘō ÓČĮÓČéÓČÜÓĘÅ, ┼Ür─½ Laß╣ģk─ü, translit-std=ISO (); ta, Ó«ćÓ«▓Ó«ÖÓ»ŹÓ«ĢÓ»ł, Ilaß╣ģkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

; arriving at Suez

Suez ( ar, ž¦┘äž│┘ł┘Ŗž│ '; ) is a seaport city (population of about 750,000 ) in north-eastern Egypt, located on the north coast of the Gulf of Suez (a branch of the Red Sea), near the southern terminus of the Suez Canal, having the same boun ...

, Egypt, on 3 January 1909.

While the fleet was in Egypt, word was received of a severe earthquake in Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

that presented an opportunity for the United States to show its friendship to Italy by offering aid to the survivors. ''Connecticut'', , , and were dispatched to Messina, Italy

Messina (, also , ) is a harbour city and the capital of the Italian Metropolitan City of Messina. It is the third largest city on the island of Sicily, and the 13th largest city in Italy, with a population of more than 219,000 inhabitants in t ...

, at once. , the Fleet's station ship at Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, ┘éž│žĘ┘åžĘ┘Ŗ┘å┘Ŗ┘ć

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

, and , a refrigerator ship fitted out in New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, were hurried to Messina

Messina (, also , ) is a harbour city and the capital of the Italian Metropolitan City of Messina. It is the third largest city on the island of Sicily, and the 13th largest city in Italy, with a population of more than 219,000 inhabitants in ...

, relieving ''Connecticut'' and ''Illinois'', so that they could continue on the cruise. Leaving Messina on 9 January 1909 the fleet stopped at Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, ╬Ø╬Ą╬¼ŽĆ╬┐╬╗╬╣Žé, Ne├Īpolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

, Italy, thence to Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

, arriving at Hampton Roads on 22 February 1909. There President Roosevelt reviewed the fleet as it passed into the roadstead and delivered an address to ''Connecticut''s officers and crew. Stirling detached from ''Connecticut'' in 1910.

The following year, he commanded the Eighth Torpedo Division, Atlantic Torpedo Fleet, his pennant in the which he also commanded as the plank owner A plankowner"U.S. Navy Style Guide", Navy.mil website (also referred to a plank ownerCutler and Cutler, p 167 and sometimes a plank holder) is an individual who was a member of the crew of a United States Navy ship or United States Coast Guard Cutt ...

captain. In 1911, he was among the first four students to attend the "long course" (16 months) at the Naval War College

The Naval War College (NWC or NAVWARCOL) is the staff college and "Home of Thought" for the United States Navy at Naval Station Newport in Newport, Rhode Island. The NWC educates and develops leaders, supports defining the future Navy and associat ...

, Newport, Rhode Island. Promoted to commander in June 1912, after completing the long course he had duty on the staff at the Naval War College. Later in 1912 he joined the as executive officer.

Submarine Flotilla, Atlantic Fleet and Submarine Base, New London

In 1914, Stirling assumed command of Submarine Flotilla, Atlantic Fleet, attached successively to the and . In April 1914, he led a flotilla of torpedo boats into Mexican waters off Vera Cruz during the

In 1914, Stirling assumed command of Submarine Flotilla, Atlantic Fleet, attached successively to the and . In April 1914, he led a flotilla of torpedo boats into Mexican waters off Vera Cruz during the Tampico Affair

The Tampico Affair began as a minor incident involving U.S. Navy sailors and the Mexican Federal Army loyal to Mexican dictator General Victoriano Huerta. On April 9, 1914, nine sailors had come ashore to secure supplies and were detained by Me ...

. In April 1915, Stirling along with Assistant Secretary of the Navy

Assistant Secretary of the Navy (ASN) is the title given to certain civilian senior officials in the United States Department of the Navy.

From 1861 to 1954, the Assistant Secretary of the Navy was the second-highest civilian office in the Depar ...

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

and Admiral Bradley A. Fiske

Rear Admiral Bradley Allen Fiske (June 13, 1854 ŌĆō April 6, 1942) was an officer in the United States Navy who was noted as a technical innovator. During his long career, Fiske invented more than a hundred and thirty electrical and mechanic ...

appeared before Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of a ...

concerning the deplorable condition of the Atlantic submarine fleet. Stirling testified that of the twelve submarines under his command outside of the Canal Zone

The Panama Canal Zone ( es, Zona del Canal de Panam├Ī), also simply known as the Canal Zone, was an unincorporated territory of the United States, located in the Isthmus of Panama, that existed from 1903 to 1979. It was located within the terri ...

, only one could get under way when the fleet was mobilized in November 1914 during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. From June 1915 until June 1916 he commanded the and served additionally as aide on the Staff of Commander Submarine Flotilla, Atlantic. Speaking before private groups, Stirling continued to raise the ire of Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the se ...

Josephus Daniels with statements criticizing the inadequate readiness of the Navy, "It is because the Navy has been the "ham bone" of politicians that the United States finds itself so unprepared on the seas. Aside from giving us ships and men we must get action from Congress that will let the Navy conduct its own affairs. We have had to take what they gave us- navy yards where we didn't want them, ships of a type we didn't need. During the last 10 years we have spent more money on our navy than Germany, yet the German navy is twice as large and twice as efficient." Stirling's critical outspokenness prompted the press to speculate, not if but when Daniels would order him court-martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

ed.

Next assigned as Commander of the newly established Submarine Flotilla

A flotilla (from Spanish, meaning a small ''flota'' (fleet) of ships), or naval flotilla, is a formation of small warships that may be part of a larger fleet.

Composition

A flotilla is usually composed of a homogeneous group of the same class ...

, New London, Connecticut

New London is a seaport city and a port of entry on the northeast coast of the United States, located at the mouth of the Thames River in New London County, Connecticut. It was one of the world's three busiest whaling ports for several decades ...

, he was also the first commander of the Submarine Base New London and the Submarine School during the period June 1916 until July 1917. In December 1916, "hydro-aeroplanes" were flown from the sub base to test their ability to spot submarines under water. Taking off from the Thames River

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after the R ...

, Stirling rode along in flights at 1,000' altitude where the fliers were able to spot the boats submerged at depth of 30ŌĆō40' in the harbor. Stirling had additional duty after the American entry into World War I

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry

...

in April 1917 commanding the . During that time, he advocated for and eventually chaired a board on submarine design. Stirling was at ease with the press

Press may refer to:

Media

* Print media or news media, commonly called "the press"

* Printing press, commonly called "the press"

* Press (newspaper), a list of newspapers

* Press TV, an Iranian television network

People

* Press (surname), a fam ...

and had a good relationship with them throughout his long and outspoken public life. He was described by the ''New York Tribune

The ''New-York Tribune'' was an American newspaper founded in 1841 by editor Horace Greeley. It bore the moniker ''New-York Daily Tribune'' from 1842 to 1866 before returning to its original name. From the 1840s through the 1860s it was the domi ...

'' in July 1917 near the end of his high-profile command of the New London submarine base and flotilla as "a fine specimen of the typical navy officer: tight lipped, kind eyed and keen faced hohad nothing to say about the plans of the base, though willing to discuss the importance of the submarine." Stirling authored a comprehensive article on the modern history, design, operation, and strategic applications of the submarine and submersible for the United States Naval Institute

The United States Naval Institute (USNI) is a private non-profit military association that offers independent, nonpartisan forums for debate of national security issues. In addition to publishing magazines and books, the Naval Institute holds se ...

''Proceedings

In academia and librarianship, conference proceedings is a collection of academic papers published in the context of an academic conference or workshop. Conference proceedings typically contain the contributions made by researchers at the confere ...

'' in July 1917. Asserting that "In the past the instruments of sea power have consisted of surface ships. New instruments now existŌĆöthe aircraft and the submarine. Air power can be overcome by superior air power. Undersea power can not be overcome by undersea power alone. To destroy this new powerŌĆöfast surface vessels and aircraft offer the best chance of success," Stirling maintained that, "The submarine is the weapon of the weaker belligerent. It constantly points a dagger at the heart of the stronger fleet; provided it actively enjoys its command of the sea."

World War I

He then fitted out and assumed command of the at her commissioning on 26 June 1917. Stirling detached from ''President Lincoln'' on 12 December 1917 and assumed command of , the ex-German raider, ''SS Kronprinz Wilhelm'', on 20 December 1917. He was awarded the Navy Cross for World War I service and cited as follows: "For distinguished service In the line of his profession as Commanding Officer of the USS ''PRESIDENT LINCOLN'' and the USS ''VON STEUBEN'', engaged in the important, exacting and hazardous duty of transporting and escorting troops and supplies to European ports through waters infested with enemy submarines and mines."Post-war

In March 1919 he was ordered to duty in command of the and in April of the next year was detached for duty as Captain of the Yard, Navy Yard, Philadelphia. While at Philadelphia, he received his Navy Cross in October 1920 that had been awarded him the previous year. In a 1921 letter to the Secretary of the Navy, during angry disagreements over technical flaws in the diesel systems supplied by Electric Boat, Stirling forcefully pointed out numerous design and reliability problems of the boats then in service, especially the new 800-ton S class. His comments sparked a tumultuous strategy, mission, and design debate that lasted for another decade, coming to a climax between 1928 and 1930 when then Commander Thomas Withers Jr., commanding officer of Submarine Division Four, called repeatedly for an offensive strategy and solo tactics similar to those employed by the Imperial German Navy during World War I. He remained at Philadelphia for two years, then served from June 1922 until June 1924 as commanding officer of the battleship , Battleship Division 5,Battle Fleet

The United States Battle Fleet or Battle Force was part of the organization of the United States Navy from 1922 to 1941.

The General Order of 6 December 1922 organized the United States Fleet, with the Battle Fleet as the Pacific presence. This f ...

, based at San Pedro, California

San Pedro ( ; Spanish: " St. Peter") is a neighborhood within the City of Los Angeles, California. Formerly a separate city, it consolidated with Los Angeles in 1909. The Port of Los Angeles, a major international seaport, is partially located wi ...

. That month Stirling was appointed chairman

The chairperson, also chairman, chairwoman or chair, is the presiding officer of an organized group such as a board, committee, or deliberative assembly. The person holding the office, who is typically elected or appointed by members of the grou ...

of the Naval Board of Inquiry

Naval Board of Inquiry and Naval Court of Inquiry are two types of investigative court proceedings, conducted by the United States Navy in response to an event that adversely affects the performance, or reputation, of the fleet or one of its shi ...

into the No. 2 turret explosion of the ''New Mexico's'' sister ship

A sister ship is a ship of the same class or of virtually identical design to another ship. Such vessels share a nearly identical hull and superstructure layout, similar size, and roughly comparable features and equipment. They often share a ...

, , on June 12, 1924, that killed 48 men.

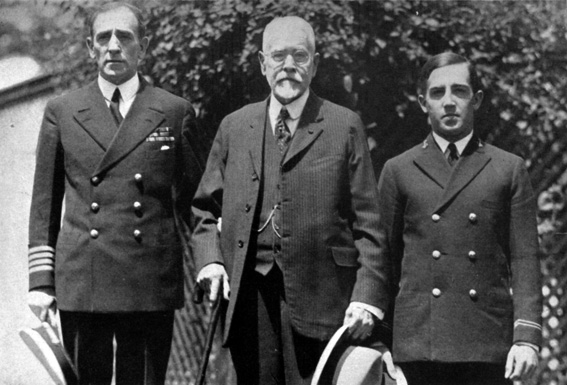

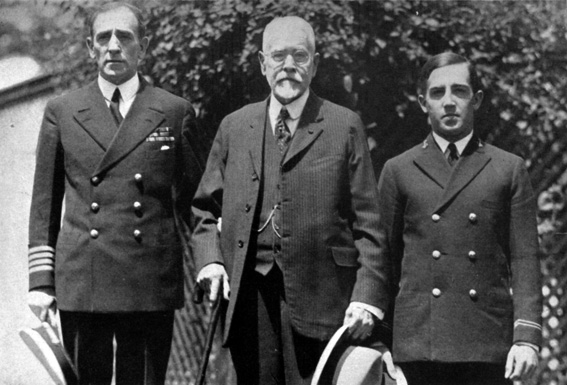

On July 20, 1924, he became Captain of the Yard, Navy Yard, Washington, D.C., with additional duty as assistant superintendent of the Naval Gun Factory. He was promoted to rear admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star "admiral" rank. It is often regarde ...

on October 6, 1926, and in December that year Stirling was designated Chief of Staff

The title chief of staff (or head of staff) identifies the leader of a complex organization such as the armed forces, institution, or body of persons and it also may identify a principal staff officer (PSO), who is the coordinator of the supporti ...

to Admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet, ...

Charles F. Hughes, commander in chief, U.S. Fleet, based at San Pedro, California

San Pedro ( ; Spanish: " St. Peter") is a neighborhood within the City of Los Angeles, California. Formerly a separate city, it consolidated with Los Angeles in 1909. The Port of Los Angeles, a major international seaport, is partially located wi ...

. At the October 27, 1927 Navy Day Ceremonies at San Pedro harbor, despite an all-day downpour, thousands of Southern Californians gathered for the festivities, including ships' tours, band performances of patriotic music and the key-note address given by Stirling, "Merchant Marine, the Navy and the Nation".

Yangtze Patrol

Sterling relieved RADM Henry H. Hough, as commander of the

Sterling relieved RADM Henry H. Hough, as commander of the Asiatic Fleet

The United States Asiatic Fleet was a fleet of the United States Navy during much of the first half of the 20th century. Before World War II, the fleet patrolled the Philippine Islands. Much of the fleet was destroyed by the Japanese by Februar ...

's storied Yangtze Patrol

The Yangtze Patrol, also known as the Yangtze River Patrol Force, Yangtze River Patrol, YangPat and ComYangPat, was a prolonged naval operation from 1854ŌĆō1949 to protect American interests in the Yangtze River's treaty ports. The Yangtze P ...

on December 2, 1927. The Patrol, formally organized in December 1919 as a U.S. Naval unit with its first commander, CAPT Thomas A. Kearney, had a legacy dating back to the mid-19th century. Then it had been the ''fanquei'' (foreign devils') warships against Imperial Peking. Following the fifteen-year Taiping Rebellion

The Taiping Rebellion, also known as the Taiping Civil War or the Taiping Revolution, was a massive rebellion and civil war that was waged in China between the Manchu-led Qing dynasty and the Han, Hakka-led Taiping Heavenly Kingdom. It lasted fr ...

, bandits proliferated on the Yangtze until Peking finally restored order. With the abdication

Abdication is the act of formally relinquishing monarchical authority. Abdications have played various roles in the succession procedures of monarchies. While some cultures have viewed abdication as an extreme abandonment of duty, in other societ ...

of the last Chinese Emperor, Puyi

Aisin-Gioro Puyi (; 7 February 1906 ŌĆō 17 October 1967), courtesy name Yaozhi (µø£õ╣ŗ), was the last emperor of China as the eleventh and final Qing dynasty monarch. He became emperor at the age of two in 1908, but was forced to abdicate on 1 ...

, following the October 1911 Wuchang Uprising

The Wuchang Uprising was an armed rebellion against the ruling Qing dynasty that took place in Wuchang (now Wuchang District of Wuhan), Hubei, China on 10 October 1911, beginning the Xinhai Revolution that successfully overthrew China's last i ...

, disorder would prevail on the river during the nearly two decades that the provincial warlord

A warlord is a person who exercises military, economic, and political control over a region in a country without a strong national government; largely because of coercive control over the armed forces. Warlords have existed throughout much of h ...

s maintained power, unchecked but for the gunboat diplomacy

In international politics, the term gunboat diplomacy refers to the pursuit of foreign policy objectives with the aid of conspicuous displays of naval power, implying or constituting a direct threat of warfare should terms not be agreeable to th ...

primarily maintained by the American and British gunboat

A gunboat is a naval watercraft designed for the express purpose of carrying one or more guns to bombard coastal targets, as opposed to those military craft designed for naval warfare, or for ferrying troops or supplies.

History Pre-steam ...

s that operated cooperatively in protecting each other's interests.Tolley, p. 177.

In 1921, the Yangtze Patrol's command billet was upgraded to a rear admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star "admiral" rank. It is often regarde ...

and it came under the operational control of the Asiatic Fleet

The United States Asiatic Fleet was a fleet of the United States Navy during much of the first half of the 20th century. Before World War II, the fleet patrolled the Philippine Islands. Much of the fleet was destroyed by the Japanese by Februar ...

. The Navy Department proclaimed that, "The mission of the Navy on the Yangtze River is to protect United States interests, lives and property, and to maintain and improve friendly relations with the Chinese people." The ships comprising the Patrol were the USS Isabel (flagship) and five gunboats, based at Hankow

Hankou, alternately romanized as Hankow (), was one of the three towns (the other two were Wuchang and Hanyang) merged to become modern-day Wuhan city, the capital of the Hubei province, China. It stands north of the Han and Yangtze Rivers whe ...

, 700 miles from the mouth of the river. The Yangtze River, the main artery of China, was then navigable for 1,750 miles, floated about 59 per cent of China's commerce, and reached over 50 per cent of its population of 159,000,000. In 1920 the United States exports to China were valued at $119,000,000 and imports from there at $227,000,000. At least half of this, and probably more, were handled via the Yangtze River. As the Navy's Annual Report stated, "Considering the perpetual banditry, piracy, and revolutionary conditions obtaining in this area, without the protection of our Navy this commerce would be practically nonexistent."

The year 1923 was a particularly chaotic one on the Yangtze. By the early 1920s, the Patrol found itself fighting river bandits while maintaining neutrality between the regional warlord

A warlord is a person who exercises military, economic, and political control over a region in a country without a strong national government; largely because of coercive control over the armed forces. Warlords have existed throughout much of h ...

s that were battling the Nationalist Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Tai ...

forces and Communist Forces in an ongoing civil war. To accommodate this difficult military balancing act and the increased perils to U.S. citizens and economic interests, in 1925 Congress authorized the construction of six new shallow-draft gunboats. Construction took place in Shanghai at Kiangnan Dock and Engineering Works during 1926ŌĆō27, with the "new six" launched in 1927ŌĆō28, and all commissioned by late 1928 during Stirling's time as "COMYANGPAT". These powerful new river gunboats, expressly designed to navigate the treacherous Yangtze and the 250 miles of rapids "upriver" from Ichang

Yichang (), alternatively romanized as Ichang, is a prefecture-level city located in western Hubei province, China. It is the third largest city in the province after the capital, Wuhan and the prefecture-level city Xiangyang, by urban populati ...

(1,000 mi. upriver) to Chungking

Chongqing ( or ; ; Sichuanese pronunciation: , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ), alternately romanized as Chungking (), is a municipality in Southwest China. The official abbreviation of the city, "" (), was approved by the State Counc ...

, were to replace the three coal-fired

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal is formed when dea ...

SpanishŌĆōAmerican War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

gunboats seized from Spain in the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, Rep├║blica de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

more than a quarter century earlier. ''Elcano'', ''Villalobos'', and ''Quiros'' had been patrolling the Yangtze since 1903; however age and their deeper drafts

Draft, The Draft, or Draught may refer to:

Watercraft dimensions

* Draft (hull), the distance from waterline to keel of a vessel

* Draft (sail), degree of curvature in a sail

* Air draft, distance from waterline to the highest point on a vessel ...

were proving increasingly problematic. The two gunboats built in the United States for service on the Yangtze, ''Palos'' and ''Monocacy'' were "obsolete even as they slid down the launching ways in 1914."

All of the new oil-burning, triple-expansion steam engine gunboats were capable of cruising at 15 knots and reaching Chungking, 1,250 miles upriver from Shanghai, at high water during the summer. Their principal armaments were two (2) high-angle 3" guns fore and aft and eight (8) .30-caliber Lewis machine guns in swivelling bullet proof mounts. The two smallest gunboats, and with the shallowest draft, could reach Chungking year-round, including the winter when the river depth decreased by as much as thirty feet. During the high-water season, they could reach Suifu, 1,500 miles upriver. and were the largest and and were next in size. These vessels gave the navy the capability it needed at a critical time of expanding operational needs. Stirling detached from the Yangtze Patrol in April 1929 and upon his return to the United States, was appointed president of the Naval Examining Board, Navy Department, Washington.

Fourteenth Naval District, Pearl Harbor, Territory of Hawaii

In September 1931 he was designated Commandant, Fourteenth Naval District, with additional duty as Commandant Naval Operating Base, Pearl Harbor, T.H. In 1932, theMassie Trial The Massie Trial, for what was known as the Massie Affair, was a 1932 criminal trial that took place in Honolulu, Hawaii Territory. Socialite Grace Fortescue, along with several accomplices, was charged with the murder of the well-known local prizef ...

was conducted in Honolulu

Honolulu (; ) is the capital and largest city of the U.S. state of Hawaii, which is in the Pacific Ocean. It is an unincorporated county seat of the consolidated City and County of Honolulu, situated along the southeast coast of the island ...

, Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only stat ...

. The Hawaiian Islands were at the time part of the 14th Naval District, commanded by Stirling. Stirling's strong belief in the guilt of the five Native Hawaiian

Native Hawaiians (also known as Indigenous Hawaiians, K─ünaka Maoli, Aboriginal Hawaiians, First Hawaiians, or simply Hawaiians) ( haw, k─ünaka, , , and ), are the indigenous ethnic group of Polynesian people of the Hawaiian Islands.

Hawaii ...

men charged with rape and assault of a young naval officer's socially prominent wife was well-known, as was his displeasure at the result of a mistrial. "Our first inclination is to seize the brutes and string them up on the trees," he stated, later tempering his reaction with, "we must give the authorities a chance to carry out the law and not interfere." Later, he defended the actions of those involved in the events that led to the homicide of one of the accused, Joseph Kahahawai

Joseph "Joe" Kahahawai Jr. (25 December 1909 ŌĆō 8 January 1932) was a Native Hawaiian prizefighter accused of the rape of Thalia Massie. He was abducted and killed after an inconclusive court case ended with a hung jury mistrial.

Early life

Kah ...

. Stirling's public statements concerning the Massie Trial would be impolitic and offensive by current social standards nearly a century later; however, they were mostly supported by the contemporary mainstream media

In journalism, mainstream media (MSM) is a term and abbreviation used to refer collectively to the various large mass news media that influence many people and both reflect and shape prevailing currents of thought.Chomsky, Noam, ''"What makes mai ...

, the Navy and Washington. Admiral William V. Pratt

William Veazie Pratt (28 February 1869 ŌĆō 25 November 1957) was an admiral in the United States Navy. He served as the President of the Naval War College from 1925 to 1927, and as the 5th Chief of Naval Operations from 1930 to 1933.

Early l ...

, Chief of Naval Operations

The chief of naval operations (CNO) is the professional head of the United States Navy. The position is a statutory office () held by an admiral who is a military adviser and deputy to the secretary of the Navy. In a separate capacity as a memb ...

, announced that, "American men will not stand for the violation of their women under any circumstances. For this crime they have taken the matter into their own hands repeatedly when they have felt that the law has failed to do justice." In a book review of Stirling's 1939 autobiography, the ''Oakland Tribune

The ''Oakland Tribune'' is a weekly newspaper published in Oakland, California, by the Bay Area News Group (BANG), a subsidiary of MediaNews Group.

Founded in 1874, the ''Tribune'' rose to become an influential daily newspaper. With the declin ...

'' wrote, "One of the most difficult tasks of Admiral Stirling's career arose when, as Commandant in Hawaii, he had to handle the Massie tragedy. The chapter devoted to this case will make unpleasant reading for those who insist that polyracial Oriental Hawaii is fit candidate for Statehood." In the 1986 made-for-television movie about the trial, ''Blood & Orchids

''Blood & Orchids'' is a 1986 made-for-TV crime-drama film. Written for the screen by Norman Katkov, it was an adaptation of Katkov's own novel which, in turn, was inspired by the 1932 Massie Trial in Honolulu, Hawaii. It was typical of many c ...

'', the name of the character representing Stirling was changed to Glenn Langdon.

Third Naval District, New York, New York

On June 30, 1933, Stirling became commandant, Third Naval District, Headquarters at New York, New York, and of theBrooklyn Navy Yard

The Brooklyn Navy Yard (originally known as the New York Navy Yard) is a shipyard and industrial complex located in northwest Brooklyn in New York City, New York. The Navy Yard is located on the East River in Wallabout Bay, a semicircular bend ...

, succeeding retiring RADM W. W. Phelps. In an interview following the change of command ceremony, Stirling was asked whether he thought battleships were obsolete, responding, "I would not go so far as that. I do think that battleships have become too expensive, but they are still the greatest offensive and defensive naval weapon. My thought is that an intelligent projectile, like a man-piloted airplane might be better than a projectile from a gun which has to go where it is sent." As to submarines, he commented, "I do think submarines make a battleship feel uncomfortable at sea but submarines and airplanes are still auxiliaries of the battleship." Stirling recalled that his last connection to the Third Naval District was in the closing months of the First World War when he was chief of staff and "trying to put the one-year-old chicken back into its eggshellŌĆö that is demobilize". Further demonstrating the characteristic dry-wit and sense of humor that made Stirling a favorite of the press of his day, after reporters had been admitted to his quarters by his aide, Commander Bruce Ware, the new commandant glanced at the varied assortment of naval pictures adorning the walls and laughingly described it as "the chamber of horrors". Stirling declined to comment on his future plans for the Brooklyn Naval Yard and when questioned about the highly publicized events of his just completed command of the Fourteenth Naval District at Hawaii, said that it was "a closed book".

Although Stirling's three years as commandant of the Third Naval District and the Brooklyn Navy Yard were during the depths of the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

, under his command the facility saw increased production and workforce. The heavy cruiser was commissioned in February 1934, the destroyer and gunboat were both built and commissioned along with a few Coast Guard cutters. Construction began on the light cruisers and . While he was commandant at New York, Stirling's official duties saw him frequently receiving foreign dignitaries, including Air Marshall Italo Balbo

Italo Balbo (6 June 1896 ŌĆō 28 June 1940) was an Italian fascist politician and Blackshirts' leader who served as Italy's Marshal of the Air Force, Governor-General of Libya and Commander-in-Chief of Italian North Africa. Due to his young a ...

during the famed Italian aviator's widely covered 1933 trans-Atlantic crossing with twenty-four Savoia-Marchetti S.55

The Savoia-Marchetti S.55 was a double-hulled flying boat produced in Italy, beginning in 1924. Shortly after its introduction, it began setting records for speed, payload, altitude and range.

Design and development

The S.55 featured many in ...

seaplanes

A seaplane is a powered fixed-wing aircraft capable of takeoff, taking off and water landing, landing (alighting) on water.Gunston, "The Cambridge Aerospace Dictionary", 2009. Seaplanes are usually divided into two categories based on their tec ...

for the Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

Century of Progress

A Century of Progress International Exposition, also known as the Chicago World's Fair, was a world's fair held in the city of Chicago, Illinois, United States, from 1933 to 1934. The fair, registered under the Bureau International des Expositi ...

. When Balbo's air armada stopped at New York City on the first leg of its return flight to Rome in July 1933, Stirling's admiral's barge

Barge nowadays generally refers to a flat-bottomed inland waterway vessel which does not have its own means of mechanical propulsion. The first modern barges were pulled by tugs, but nowadays most are pushed by pusher boats, or other vessels ...

met Balbo's plane when it landed in Jamaica Bay

Jamaica Bay is an estuary on the southern portion of the western tip of Long Island, in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. The estuary is partially man-made, and partially natural. The bay connects with Lower New York Bay to the west, ...

off Floyd Bennett Field

Floyd Bennett Field is an airfield in the Marine Park neighborhood of southeast Brooklyn in New York City, along the shore of Jamaica Bay. The airport originally hosted commercial and general aviation traffic before being used as a naval air ...

. Stirling and his Army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''arm─üre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

counterpart, Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Dennis E. Nolan, commanding general of Second Corps Area, in charge of army units and facilities in New York, New Jersey, Delaware and Puerto Rico, accompanied Balbo's police escort

A police escort, also known as a law enforcement escort, is a service offered by police and law enforcement to assist in transporting important individuals or resources.

This is done by means of assigning police vehicles, primarily cars or motor ...

motorcade to the Mayflower Hotel. Stirling had requested an allowance from the Navy Department for the purpose of hosting a dinner for Balbo on his first night in New York. Receiving only $50 from Washington, the socially-connected and popular Stirling was undeterred. "Through the support of men of means who were Navy admirers, I gave to General Balbo and his officers a most elaborate dinner at the Columbian Yacht Club on the Hudson River, now demolished in the development of the Park project. How such a dinner could be given, with over a hundred guests and champagne flowing freely, on the small voucher that I signed, would be no mystery when the guest list is read. Among them were Vincent Astor

William Vincent Astor (November 15, 1891 ŌĆō February 3, 1959) was an American businessman, philanthropist, and member of the prominent Astor family.

Early life

Called Vincent, he was born in New York City on November 15, 1891. Astor was the eld ...

, Grover Whalen, Ellery W. Stone, E. J. Sadler, and W. S. Farish, all public spirited citizens and some of them members of the Naval Reserve. It has always been difficult for the services to interest Congress in the advantage of appropriating sufficient funds for official entertaining. Balbo enjoyed himself at the dinner, and we were all glad to have such an intimate view of him and his daring men. I regretted that I did not speak Italian or he English, but there was a fellowship developed that evening between the Italian flyers and our other guests, in spite of the handicap of language. I was surprised months later to receive from the great Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

the decoration of the Crown of Italy

A crown is a traditional form of head adornment, or hat, worn by monarchs as a symbol of their power and dignity. A crown is often, by extension, a symbol of the monarch's government or items endorsed by it. The word itself is used, partic ...

. It was in recognition of the Navy's help to Balbo and his airplanes while in New York."

Stirling retired on May 1, 1936, when he was transferred to the Navy Retired List, having reached the statutory retirement age of 64. He and Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Dennis E. Nolan had been born eight days apart and faced mandatory service retirement at the same time. The two retiring two-star flag officers, who had frequently appeared together during their respective last commands, were jointly honored with a retirement banquet at the Hotel St. George by naval, military and New York society, led by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

's mother, Sara Roosevelt

Sara Ann Roosevelt ( Delano; September 21, 1854 ŌĆō September 7, 1941) was the second wife of James Roosevelt I (from 1880), the mother of President of the United States Franklin Delano Roosevelt, her only child, and subsequently the mother ...

, who posed for photos arm in arm with both men and declared, "I am very fond of and have the highest regard and admiration for both of the honored guests"

Post Naval career

Admiral Stirling, self-styled "stormy petrel" of the Naval Service, devoted his energies after retirement to writing books, newspaper articles and lecturing. Outspoken and critical of naval policies and procedures as well as U. S. international policies, he had long urged a two-ocean Navy second to none. He published a controversial anti-Soviet article in 1935 while still on active duty that evoked a proclamation from the Secretary of the Navy that active duty naval officers were not to speak out on international policy. He urged U.S. intervention against Germany in 1939 and failing to interest the country, pleaded that the American people at least pray for a British-French victory. Speaking before the national convention of theVeterans of Foreign Wars

The Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW), formally the Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States, is an organization of US war veterans, who, as military service members fought in wars, campaigns, and expeditions on foreign land, waters, or a ...

in Philadelphia that year, Stirling warned that "the framing of neutrality laws to keep us out of warŌĆöwithout taking into consideration the terrible result to us of a dictatorial victoryŌĆöis like 'whistling in the dark' or 'fiddling while Rome is burning. There is but one way to keep us out of war; for the war not to happen. Therefore, as an important organ of this complicated world, we should, instead of keeping out of foreign disputes that will threaten our security and prosperity, go into them with both feet. The present neutrality law, placing an embargo on arms to nations at war, surely will cause us great economic painsŌĆöif not complete disaster to our entire industrial structure; for in the next war we shall find that all goods and supplies will be declared contraband by all belligerents." When Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

's Italian air force attacked and bombed Haifa

Haifa ( he, ūŚųĄūÖūżųĖūö ' ; ar, žŁ┘Ä┘Ŗ┘Æ┘ü┘Äž¦ ') is the third-largest city in IsraelŌĆöafter Jerusalem and Tel AvivŌĆöwith a population of in . The city of Haifa forms part of the Haifa metropolitan area, the third-most populous metropol ...

, in the British mandate of Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

in July 1940, destroying oil refineries and storage tanks, Stirling penned an article which drew national attention in which he proclaimed that "all the high cards" in the Mediterranean are in the hands of "Italian air power". Just two days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii, ju ...

, Stirling wrote a prescient article wherein he laid out eight predicted Japanese strategic goals and concluded ultimate Japanese defeat, "To this naval observer, intimately familiar with the whole pattern of events in the PacificŌĆömilitary, political and economicŌĆöfor many years, the Japanese action appears suicidal. ... We may be in for a long and hard war, but the Japanese can not win. We are likely to suffer initial reverses but for them we will obtain a terrible vengeance."

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countriesŌĆöincluding all of the great powersŌĆöforming two opposin ...

, Stirling penned scores of articles as a syndicated columnist

A columnist is a person who writes for publication in a series, creating an article that usually offers commentary and opinions. Columns appear in newspapers, magazines and other publications, including blogs. They take the form of a short essay ...

expressing his opinions on war-time strategies and tactics, under the byline

The byline (or by-line in British English) on a newspaper or magazine article gives the name of the writer of the article. Bylines are commonly placed between the headline and the text of the article, although some magazines (notably ''Reader's D ...

, "United Press

United Press International (UPI) is an American international news agency whose newswires, photo, news film, and audio services provided news material to thousands of newspapers, magazines, radio and television stations for most of the 20th c ...

Naval Critic" or "United Press Naval Analyst". In 1942, he advocated building a fleet of small, wooden, V-bottom, 30ŌĆō60' long craft, capable of 30 knots, with two machine guns and six depth charge racks, manned by 3 to 7 men, to patrol the 35,000 miles of U.S. coastline and protect shipping. When Stirling sought to return to active duty in 1944, Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the se ...

James Forrestal

James Vincent Forrestal (February 15, 1892 ŌĆō May 22, 1949) was the last Cabinet-level United States Secretary of the Navy and the first United States Secretary of Defense.

Forrestal came from a very strict middle-class Irish Catholic fami ...

wrote back that there was no post available "suitable to your rank and attainments". Yates Stirling's last book, touting the strategic importance of his beloved Navy, "Why Sea Power Will Win the War", was published in 1944.

Personal life

Stirling married the former Adelaide Egbert, daughter of

Stirling married the former Adelaide Egbert, daughter of Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

Harry C. Egbert, in 1903 when he was 31. They had five children, two boys and three girls. His eldest son, Yates Stirling, III became a captain in the Navy. His younger son, Harry, also served in the Navy and attained the rank of commander.

RADM Stirling was a hereditary companion of the California Commandery of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States

The Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States (MOLLUS), or simply the Loyal Legion is a United States patriotic order, organized April 15, 1865, by three veteran officers of the Army. The original membership was composed of members ...

by right of his father's service in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 ŌĆō May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

having been elected to membership while an ensign in 1899./ref>

Death

Rear Admiral Stirling died in his sleep on January 27, 1948, after three months' illness in Baltimore, Maryland, his home for many years, and was buried atArlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is one of two national cemeteries run by the United States Army. Nearly 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington, Virginia. There are about 30 funerals conducted on weekdays and 7 held on Sa ...

. He and his wife had two sons, Captain Yates Stirling, III, USN (Ret.) of Norfolk, Virginia, and Commander Harry E. Stirling USN; and three daughters, Katharine (Mrs. William R. Ilk) of Los Angeles, California

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world' ...

, and Misses Ellen and Adelaide Stirling of Baltimore.

Dates of rank

:

United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (US Naval Academy, USNA, or Navy) is a federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as Secretary of the Navy. The Naval Academy ...

Passed Naval Cadet

Officer Cadet is a rank held by military cadets during their training to become commissioned officers. In the United Kingdom, the rank is also used by members of University Royal Naval Units, University Officer Training Corps and University A ...

ŌĆō June 3, 1892

* Commodore

Commodore may refer to:

Ranks

* Commodore (rank), a naval rank

** Commodore (Royal Navy), in the United Kingdom

** Commodore (United States)

** Commodore (Canada)

** Commodore (Finland)

** Commodore (Germany) or ''Kommodore''

* Air commodore ...

ŌĆō no longer a rank in the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

, was previously reserved for wartime use and was not in use at the time of Stirling's promotion to Flag Rank

A flag officer is a commissioned officer in a nation's armed forces senior enough to be entitled to fly a flag to mark the position from which the officer exercises command.

The term is used differently in different countries: