Yangsheng (Daoism) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In

''Shēng'' (生) means

:1. Live, be alive, exist; life; living being; the act of living; lifetime, lifespan.

:2. Cause to live, bring into existence; give birth to, bear; originate; come forth, appear; to grow, develop.

:3. Fresh; green; unripe, raw; uncooked; unfamiliar; unacquainted; unskillful, clumsy, inept, awkward, unrefined.

:4. Nature, natural instinct, inherent character, intrinsic quality. (Kroll 2017: 408, condensed).

Ancient characters for ''sheng'' (生) were

''Shēng'' (生) means

:1. Live, be alive, exist; life; living being; the act of living; lifetime, lifespan.

:2. Cause to live, bring into existence; give birth to, bear; originate; come forth, appear; to grow, develop.

:3. Fresh; green; unripe, raw; uncooked; unfamiliar; unacquainted; unskillful, clumsy, inept, awkward, unrefined.

:4. Nature, natural instinct, inherent character, intrinsic quality. (Kroll 2017: 408, condensed).

Ancient characters for ''sheng'' (生) were

In

In

Classics from the

Classics from the

The Jin dynasty (266–420)#Eastern Jin (317–420), Eastern Jin dynasty official and ''Liezi'' commentator Zhang Zhan 張湛 (fl. 370) wrote one of the most influential works of the Six Dynasties period, the ''Yangsheng yaoji'' (養生要集, "Essentials of Nourishing Life"). For ''yangsheng'' health and immortality seekers, this text is said to be equally important as the ''Daodejing'' and ''Huangtingjing'' (黃庭經, "Yellow Court Classic"), it was "a widely available source of information for the educated but not necessarily initiated reader", until it was lost during the eighth century (Despeux 2008: 1149). The ''Yangsheng yaoji'' is important in the history of ''yangsheng'' techniques for three reasons: it cites from several earlier works that would have otherwise been lost, it presents a standard textbook model for many later works, and it is the earliest known text to systematize and classify the various longevity practices into one integrated system (Engelhardt 2000: 91). In the present day, the text survives in numerous fragments and citations, especially in the ''Yangxing yanming lu'' (養性延命錄, "On Nourishing Inner Nature and Extending Life"), ascribed to Tao Hongjing (456–536), Sun Simiao's 652 ''Qianjin fang'' (千金方, "Prescriptions Worth a Thousand Gold [Pieces]"), as well as in early Japanese medical texts such as the 984 ''Ishinpō'' ("Methods from the Heart of Medicine"). (Barrett and Kohn 2008: 1151).

During the Northern and Southern dynasties (420–589), ''yangsheng'' incorporated Chinese Buddhism, Chinese Buddhist meditation techniques (especially ''Ānāpānasati'' "mindfulness of breathing") and Indian gymnastic exercises. Daoist ''zuowang'' ("sitting and forgetting") and ''qingjing'' (清静, "clarity and stillness") meditating were influenced by Buddhist practices (Despeux 2008: 1149).

The Jin dynasty (266–420)#Eastern Jin (317–420), Eastern Jin dynasty official and ''Liezi'' commentator Zhang Zhan 張湛 (fl. 370) wrote one of the most influential works of the Six Dynasties period, the ''Yangsheng yaoji'' (養生要集, "Essentials of Nourishing Life"). For ''yangsheng'' health and immortality seekers, this text is said to be equally important as the ''Daodejing'' and ''Huangtingjing'' (黃庭經, "Yellow Court Classic"), it was "a widely available source of information for the educated but not necessarily initiated reader", until it was lost during the eighth century (Despeux 2008: 1149). The ''Yangsheng yaoji'' is important in the history of ''yangsheng'' techniques for three reasons: it cites from several earlier works that would have otherwise been lost, it presents a standard textbook model for many later works, and it is the earliest known text to systematize and classify the various longevity practices into one integrated system (Engelhardt 2000: 91). In the present day, the text survives in numerous fragments and citations, especially in the ''Yangxing yanming lu'' (養性延命錄, "On Nourishing Inner Nature and Extending Life"), ascribed to Tao Hongjing (456–536), Sun Simiao's 652 ''Qianjin fang'' (千金方, "Prescriptions Worth a Thousand Gold [Pieces]"), as well as in early Japanese medical texts such as the 984 ''Ishinpō'' ("Methods from the Heart of Medicine"). (Barrett and Kohn 2008: 1151).

During the Northern and Southern dynasties (420–589), ''yangsheng'' incorporated Chinese Buddhism, Chinese Buddhist meditation techniques (especially ''Ānāpānasati'' "mindfulness of breathing") and Indian gymnastic exercises. Daoist ''zuowang'' ("sitting and forgetting") and ''qingjing'' (清静, "clarity and stillness") meditating were influenced by Buddhist practices (Despeux 2008: 1149).

''Yangsheng'' practices underwent significant changes from the Song dynasty (960-1279) onward. They integrated many elements drawn from ''neidan'' ("inner alchemy") practices, and aroused the interest of scholars. For the Song dynasty alone, there are about twenty books on the subject. An important author of the time was Zhou Shouzhong (周守中), who wrote the ''Yangsheng leizuan'' (養生類纂, "Classified Compendium on Nourishing Life"), the ''Yangsheng yuelan'' (養生月覽, "Monthly Readings on Nourishing Life"), and other books (Despeux 2008: 1150). Famous Song Scholar-official, literati and poets, such as Su Shi (1007-1072) and Su Dongpo (1037-1101), wrote extensively about their longevity practices. The Song author Chen Zhi's (陳直) ''Yanglao Fengqin Shu'' (養老奉親書, "Book on Nourishing Old Age and Taking Care of One's Parents") was the first Chinese work dealing exclusively with geriatrics (Engelhardt 2000: 81). Along the development of Neo-Confucianism and the growth of syncretism among Daoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism in the Ming dynasty, Ming (1368–1644) and Qing dynasty, Qing (1636–1912) periods, a number of ethical elements were incorporated into ''yangsheng'' (Despeux 2008: 1150).

During the Ming period, various collections and compendia of longevity writings appeared. Hu Wenhuan (胡文焕), editor of the 1639 edition ''Jiuhuang Bencao'' ("Famine Relief Herbal"), wrote the main work on ''yangsheng'', the c. 1596 ''Shouyang congshu'' (壽養叢書, "Collectanea on Longevity and Nourishment [of Life]"), which includes the ''Yangsheng shiji'' (養生食忌, "Prohibitions on Food for Nourishing Life") and the ''Yangsheng daoyin fa'' (養生導引法, "''Daoyin'' Methods for Nourishing Life"). Some works are inclusive treatments of diverse longevity techniques, for example, the dramatist Gao Lian (dramatist), Gao Lian's (fl. 1573-1581) ''Zunsheng bajian'' (遵生八笺, "Eight Essays on Being in Accord with Life") described ''yangsheng'' diets, breathing methods, and medicines. Other works focus entirely on a single method, such as ''Tiaoxi fa'' (調息法, "Breath Regulation Methods") by the Neo-Confucian philosopher Wang Ji (philosopher), Wang Ji (1498-1582) (Engelhardt 2000: 81). Another new development under the Ming is the increased integration and legitimization of ''yangsheng'' techniques into medical literature. For example, Yang Jizhou's (楊繼洲) extensive 1601 ''Zhenjiu dacheng'' (針灸大成, "Great Compendium on Acupuncture and Moxibustion"), which remains a classic to the present day, presents gymnastic exercises for the various ''qi''-Meridian (Chinese medicine), meridians (Engelhardt 2000: 82).

Unlike the Ming dynasty, the Qing dynasty produced no important work on ''yangsheng''. In the twentieth century, ''yangsheng'' evolved into the modern Westernized science of ''weisheng'' (衛生, "hygiene, health, sanitation") on the one hand, and into ''qigong'' on the other (Despeux 2008: 1150).

Dear's anthropological study of ''yangsghengs popularity and commercialization in early twenty-first century China makes a contrast with Qigong fever, ''Qigong'' fever, a 1980s and 1990s Chinese social phenomenon in which the practice of ''qigong'' rose to extraordinary popularity, estimated to have reached a peak number of practitioners between 60 and 200 million. While the Qigong fever had a "somewhat austere and Salvationist aspect", the more recent Yangsheng fever, "which covers so much of the same ground in the quest for health and identity, has a certain low-key decadence about it." For instance, using the term ''yangsheng'' to advertise deluxe villas in the suburbs, luxury health spas, extravagantly packaged expensive medicines like ''chongcao'' (蟲草, ''Ophiocordyceps sinensis''), and tourism to naturally beautiful landscapes, "are some of the markers of the new ''Yangsheng''." (Dear 2012: 29).

''Yangsheng'' practices underwent significant changes from the Song dynasty (960-1279) onward. They integrated many elements drawn from ''neidan'' ("inner alchemy") practices, and aroused the interest of scholars. For the Song dynasty alone, there are about twenty books on the subject. An important author of the time was Zhou Shouzhong (周守中), who wrote the ''Yangsheng leizuan'' (養生類纂, "Classified Compendium on Nourishing Life"), the ''Yangsheng yuelan'' (養生月覽, "Monthly Readings on Nourishing Life"), and other books (Despeux 2008: 1150). Famous Song Scholar-official, literati and poets, such as Su Shi (1007-1072) and Su Dongpo (1037-1101), wrote extensively about their longevity practices. The Song author Chen Zhi's (陳直) ''Yanglao Fengqin Shu'' (養老奉親書, "Book on Nourishing Old Age and Taking Care of One's Parents") was the first Chinese work dealing exclusively with geriatrics (Engelhardt 2000: 81). Along the development of Neo-Confucianism and the growth of syncretism among Daoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism in the Ming dynasty, Ming (1368–1644) and Qing dynasty, Qing (1636–1912) periods, a number of ethical elements were incorporated into ''yangsheng'' (Despeux 2008: 1150).

During the Ming period, various collections and compendia of longevity writings appeared. Hu Wenhuan (胡文焕), editor of the 1639 edition ''Jiuhuang Bencao'' ("Famine Relief Herbal"), wrote the main work on ''yangsheng'', the c. 1596 ''Shouyang congshu'' (壽養叢書, "Collectanea on Longevity and Nourishment [of Life]"), which includes the ''Yangsheng shiji'' (養生食忌, "Prohibitions on Food for Nourishing Life") and the ''Yangsheng daoyin fa'' (養生導引法, "''Daoyin'' Methods for Nourishing Life"). Some works are inclusive treatments of diverse longevity techniques, for example, the dramatist Gao Lian (dramatist), Gao Lian's (fl. 1573-1581) ''Zunsheng bajian'' (遵生八笺, "Eight Essays on Being in Accord with Life") described ''yangsheng'' diets, breathing methods, and medicines. Other works focus entirely on a single method, such as ''Tiaoxi fa'' (調息法, "Breath Regulation Methods") by the Neo-Confucian philosopher Wang Ji (philosopher), Wang Ji (1498-1582) (Engelhardt 2000: 81). Another new development under the Ming is the increased integration and legitimization of ''yangsheng'' techniques into medical literature. For example, Yang Jizhou's (楊繼洲) extensive 1601 ''Zhenjiu dacheng'' (針灸大成, "Great Compendium on Acupuncture and Moxibustion"), which remains a classic to the present day, presents gymnastic exercises for the various ''qi''-Meridian (Chinese medicine), meridians (Engelhardt 2000: 82).

Unlike the Ming dynasty, the Qing dynasty produced no important work on ''yangsheng''. In the twentieth century, ''yangsheng'' evolved into the modern Westernized science of ''weisheng'' (衛生, "hygiene, health, sanitation") on the one hand, and into ''qigong'' on the other (Despeux 2008: 1150).

Dear's anthropological study of ''yangsghengs popularity and commercialization in early twenty-first century China makes a contrast with Qigong fever, ''Qigong'' fever, a 1980s and 1990s Chinese social phenomenon in which the practice of ''qigong'' rose to extraordinary popularity, estimated to have reached a peak number of practitioners between 60 and 200 million. While the Qigong fever had a "somewhat austere and Salvationist aspect", the more recent Yangsheng fever, "which covers so much of the same ground in the quest for health and identity, has a certain low-key decadence about it." For instance, using the term ''yangsheng'' to advertise deluxe villas in the suburbs, luxury health spas, extravagantly packaged expensive medicines like ''chongcao'' (蟲草, ''Ophiocordyceps sinensis''), and tourism to naturally beautiful landscapes, "are some of the markers of the new ''Yangsheng''." (Dear 2012: 29).

Etymology of the Word “Macrobiotic:s”[''sic''

and Its Use in Modern Chinese Scholarship], ''Sino-Platonic Papers'' 113. *Dear, David (2012),

Chinese Yangsheng: Self-help and Self-image

, ''Asian Medicine'' 7: 1-33. *DeFrancis, John, genl. ed. (1996), ''ABC Chinese-English Dictionary'', University of Hawaii Press. *Despeux, Catherine (2008), "Yangsheng 養生 Nourishing Life", in Fabrizio Pregadio, ed., ''The Encyclopedia of Taoism'', Routledge, 1148-1150. *Engelhardt, Ute (1989), "Qi for Life: Longevity in the Tang," in Kohn (1989) ''Taoist Meditation and Longevity Techniques'', University of Michigan, 263-96. *Engelhardt, Ute (2000), "Longevity Techniques and Chinese Medicine," in Kohn ''Daoism Handbook'', E. J. Brill, 74-108. *Forke, Alfred, tr. (1907)

Lun-hêng, Part 1, Philosophical Essays of Wang Ch'ung

Harrassowitz. *Harper, Donald (1998, 2009), ''Early Chinese Medical Literature: The Mawangdui Medical Manuscripts'', Kegan Paul. *Kohn, Livia, ed. (1989), ''Taoist Meditation and Longevity Techniques'', University of Michigan. *Lau, D. C. (1970)

''Mencius''

Penguin Books. *Mair, Victor H., tr. (1994), ''Wandering on the Way, Early Taoist Tales and Parables of Chuang Tzu'', Bantam. *Mair, Victor H. (2007), ''The Art of War: Sun Zi's Military Method'', Columbia University Press. *Major, John S., Sarah Queen, Andrew Meyer, and Harold D. Roth (2010), ''The Huainanzi: A Guide to the Theory and Practice of Government in Early Han China'', Columbia University Press. *Maspero, Henri (1981), ''Taoism and Chinese Religion'', tr. by Frank A. Kierman, University of Massachusetts Press. *Needham, Joseph and Lu Gwei-djen (1974), ''Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 5 Chemistry and Chemical Technology Part 2: Spagyrical Discovery and Inventions: Magisteries of Gold and Immortality'', Cambridge University Press. *Needham, Joseph and Lu Gwei-djen (2000), ''Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 6, Biology and Biological Technology, Part VI: Medicine'', Cambridge University Press. *Theobald, Ulrich (2010), "Baopuzi 抱朴子", Chinaknowledge. *Ware, James R., tr. (1966), ''Alchemy, Medicine and Religion in the China of A.D. 320: The'' Nei Pien'' of Ko Hung'', Dover. *Yang, Dolly (2022), "Therapeutic Exercise in the Medical Practice of Sui China (581-618 CE)", in ''Routledge Handbook of Chinese Medicine'', ed. by Vivienne Lo, Michael Stanley-Baker, and Dolly Yang, 109-119, Routledge.

Daoist Health Cultivation

FYSK: Daoist Culture Centre, 19 September 2009 {{Traditional Chinese medicine Life extension Meditation Taoist practices Traditional Chinese medicine

religious Taoism

Chinese theology, which comes in different interpretations according to the classic texts and the common religion, and specifically Confucian, Taoist and other philosophical formulations, is fundamentally monistic, that is to say it sees the w ...

and Traditional Chinese medicine

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is an alternative medical practice drawn from traditional medicine in China. It has been described as "fraught with pseudoscience", with the majority of its treatments having no logical mechanism of action ...

, ''yangsheng'' (養生, "nourishing life"), refers to various self-cultivaton practices aimed at enhancing health and longevity. ''Yangsheng'' techniques include calisthenics

Calisthenics (American English) or callisthenics (British English) ( /ˌkælɪsˈθɛnɪks/) is a form of strength training consisting of a variety of movements that exercise large muscle groups (gross motor movements), such as standing, graspi ...

, self-massage, breath exercises, meditation

Meditation is a practice in which an individual uses a technique – such as mindfulness, or focusing the mind on a particular object, thought, or activity – to train attention and awareness, and achieve a mentally clear and emotionally cal ...

, internal

Internal may refer to:

*Internality as a concept in behavioural economics

*Neijia, internal styles of Chinese martial arts

*Neigong or "internal skills", a type of exercise in meditation associated with Daoism

*''Internal (album)'' by Safia, 2016

...

and external

External may refer to:

* External (mathematics), a concept in abstract algebra

* Externality

In economics, an externality or external cost is an indirect cost or benefit to an uninvolved third party that arises as an effect of another party' ...

Taoist alchemy

Chinese alchemy is an ancient Chinese scientific and technological approach to alchemy, a part of the larger tradition of Taoist / Daoist body-spirit cultivation developed from the traditional Chinese understanding of medicine and the body. Accor ...

, sexual activities

Human sexual activity, human sexual practice or human sexual behaviour is the manner in which humans experience and express their sexuality. People engage in a variety of sexual acts, ranging from activities done alone (e.g., masturbation) t ...

, and dietetics

A dietitian, medical dietitian, or dietician is an expert in identifying and treating disease-related malnutrition and in conducting medical nutrition therapy, for example designing an enteral tube feeding regimen or mitigating the effects of ...

.

Most ''yangsheng'' methods are intended to increase longevity, a few to achieve "immortality"— in the specialized Taoist sense of transforming into a ''Xian'' ("transcendent", who typically dies after a few centuries, loosely translated as "immortal"). While common longevity practices (such as eating a healthy diet or exercising) can increase one's lifespan and well-being, some esoteric transcendence practices (such as "grain avoidance" diets where an adept eats only '' qi''/breath instead of foodstuffs, or drinking frequently poisonous Taoist alchemical elixirs of life) can ironically be deadly.

Terminology

The word ''yangsheng'' is a linguisticcompound

Compound may refer to:

Architecture and built environments

* Compound (enclosure), a cluster of buildings having a shared purpose, usually inside a fence or wall

** Compound (fortification), a version of the above fortified with defensive struct ...

of two common Chinese words. ''Yǎng'' (養) means

:1. Nurture; rear, raise, foster; nourish; tend, care for, look after.

:2. Support by providing basic necessities; provide for; maintain, keep in good condition; preserve; watch over.

:3. Train; groom; educate in the proper way of carrying out one's responsibilities; cultivate.

:4. Nurse; treat so as to aid in recuperation. (Kroll 2017: 533, condensed)

Besides the usual third tone

In music, 72 equal temperament, called twelfth-tone, 72-TET, 72- EDO, or 72-ET, is the tempered scale derived by dividing the octave into twelfth-tones, or in other words 72 equal steps (equal frequency ratios). Each step represents a frequency ...

reading ''yǎng'' this character has an uncommon alternate fourth tone pronunciation ''yàng'' (養) meaning "support and take care of (especially one's parents)". For instance, ''yàngshēng'' occurs in the late 4th-century BCE '' Mengzi'', "Keeping one's parents when they are alive ��生者is not worth being described as of major importance; it is treating them decently when they die that is worth such a description." (1.13, tr. Lau 1970: 130). Note that the regular and seal

Seal may refer to any of the following:

Common uses

* Pinniped, a diverse group of semi-aquatic marine mammals, many of which are commonly called seals, particularly:

** Earless seal, or "true seal"

** Fur seal

* Seal (emblem), a device to impr ...

characters (e.g., 養) combine a ''yáng'' (羊, "sheep", originally picturing a ram's head) phonetic component and ''shí'' (食, "food, feed") radical

Radical may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

*Radical politics, the political intent of fundamental societal change

*Radicalism (historical), the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and ...

denoting "feed animals", while the ancient oracle

An oracle is a person or agency considered to provide wise and insightful counsel or prophetic predictions, most notably including precognition of the future, inspired by deities. As such, it is a form of divination.

Description

The word '' ...

and bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals, such as phosphorus, or metalloids such ...

characters (e.g., 䍩) combine ''yáng'' (羊, "sheep) and ''pū'' (攵, "hit lightly; tap") denoting "shepherd; tend sheep".

pictographs

A pictogram, also called a pictogramme, pictograph, or simply picto, and in computer usage an icon, is a graphic symbol that conveys its meaning through its pictorial resemblance to a physical object. Pictographs are often used in writing and gr ...

showing a plant growing out of the earth (土).

The unabridged Chinese-Chinese ''Hanyu Da Cidian

The ''Hanyu Da Cidian'' () is the most inclusive available Chinese dictionary. Lexicographically comparable to the ''Oxford English Dictionary'', it has diachronic coverage of the Chinese language, and traces usage over three millennia from Chi ...

'' ("Comprehensive Chinese Word Dictionary"), lexicographically

In mathematics, the lexicographic or lexicographical order (also known as lexical order, or dictionary order) is a generalization of the alphabetical order of the dictionaries to sequences of ordered symbols or, more generally, of elements of a ...

comparable to the ''Oxford English Dictionary

The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (''OED'') is the first and foundational historical dictionary of the English language, published by Oxford University Press (OUP). It traces the historical development of the English language, providing a com ...

'', gives five definitions of ''yǎngshēng'' (養生):

:1. 保养生命; 维持生. ake good care of one's health, preserve one's lifespan:2. 摄养身心使长寿. ourish one's body and mind for longevity:3. 畜养生物. aise animals:4. 谓驻扎在物产丰富, 便于生活之处. e stationed in a healthy location with abundant produce:5. 生育. ive birth; raiseThe specialized fourth meaning quotes Zhang Yu's (張預) commentary to ''The Art of War

''The Art of War'' () is an ancient Chinese military treatise dating from the Late Spring and Autumn Period (roughly 5th century BC). The work, which is attributed to the ancient Chinese military strategist Sun Tzu ("Master Sun"), is com ...

'' that says, "An army ordinarily likes heights and dislikes depths, values brightness and disparages darkness, nourishes itself on vitality and places itself on solidity. Thus it will not fall prey to a host of ailments and may be declared 'invincible'." (9, tr. Mair 2007: 109)]. The ''Hanyu Da Cidian'' also gives a definition of ''yàngshēng'' (養生), see the ''Mencius'' above:

:1. 指奉养父母. upport and take care of one's parents(1984: 12, 522).

The idea of ''yang'' (養, "nourishing") is prominent in Chinese thought. There is a semantic field

In linguistics, a semantic field is a lexical set of words grouped semantically (by meaning) that refers to a specific subject.Howard Jackson, Etienne Zé Amvela, ''Words, Meaning, and Vocabulary'', Continuum, 2000, p14. The term is also used in ...

that includes ''yangsheng'' (養生, "nourish life"), ''yangxing'' (養形, "nourish the body"), ''yangshen'' (養身, "nourish the whole person"), ''yangxing'' (養性, "nourish the inner nature"), ''yangzhi'' (養志, "nourish the will"), and ''yangxin'' (養心, "nourish the mind") (Despeux 2008: 1148).

Translations

"Nourishing life" is the common English translation equivalent for ''yangsheng''. Some examples of other renderings include "keep in good health; nourish one's vital principle" (DeFrancis 1996), "nurturing vitality", "nourishing the vitality" (Needham and Lu 2000: 72, 115), longevity techniques" (Engelhardt 2000: 74), and "nurturing life”, “cultivating life” (Dear 2012: 1). Some sinologists translate ''yangsheng'' and ''yangxing'' (養性) as "macrobiotic", using Englishmacrobiotic

A macrobiotic diet (or macrobiotics) is a fad diet based on ideas about types of food drawn from Zen Buddhism. The diet tries to balance the supposed yin and yang elements of food and cookware. Major principles of macrobiotic diets are to reduce ...

in its original meaning "Inclined or tending to prolong life; relating to the prolongation of life" instead of its more familiar macrobiotic diet

A macrobiotic diet (or macrobiotics) is a fad diet based on ideas about types of food drawn from Zen Buddhism. The diet tries to balance the supposed yin and yang elements of food and cookware. Major principles of macrobiotic diets are to reduce ...

meaning, "Of or pertaining to a Zen Buddhist dietary system intended to prolong life, comprising pure vegetable foods, brown rice, etc." (''OED

The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (''OED'') is the first and foundational historical dictionary of the English language, published by Oxford University Press (OUP). It traces the historical development of the English language, providing a co ...

'' 2009). The first example was Alfred Forke's 1907 translation of Wang Chong

Wang Chong (; 27 – c. 97 AD), courtesy name Zhongren (仲任), was a Chinese astronomer, meteorologist, naturalist, philosopher, and writer active during the Han Dynasty. He developed a rational, secular, naturalistic and mechanistic account ...

's 80 CE ''Lunheng

The ''Lunheng'', also known by numerous English translations, is a wide-ranging Chinese classic text by Wang Chong (27- ). First published in 80, it contains critical essays on natural science and Chinese mythology, philosophy, and literature ...

'', mentioned below. Wang's autobiography says that near the end of his life, "he wrote a book on Macrobiotics ��性in sixteen chapters. To keep himself alive, he cherished the vital fluid ��氣" (tr. Forke 1907: 348). Joseph Needham

Noel Joseph Terence Montgomery Needham (; 9 December 1900 – 24 March 1995) was a British biochemist, historian of science and sinologist known for his scientific research and writing on the history of Chinese science and technology, in ...

and Lu Gwei-djen

Lu Gwei-djen (; July 22, 1904 – November 28, 1991) was a Chinese biochemist and historian. She was an expert on the history of science and technology in China and a researcher of nutriology. She was an important researcher and co-author of ...

say,

Macrobiotics is a convenient term for the belief that it is possible to prepare, with the aid of botanical, zoological, mineralogical and above all chemical, knowledge, drugs or elixirs 'dan'' 丹which will prolong human life beyond old age 'shoulao'' 壽老 rejuvenating the body and its spiritual parts so that the adept 'zhenren'' 真人can endure through centuries of longevity 'changsheng'' 長生 finally attaining the status of eternal life and arising with etherealised body a true Immortal 'shengxian'' 升仙(Needham and Lu 1974: 11).Donald Harper translates ''yangsheng'' and ''changsheng'' (長生, "long life") in the

Mawangdui Silk Texts The Mawangdui Silk Texts () are Chinese philosophical and medical works written on silk which were discovered at the Mawangdui site in Changsha, Hunan, in 1973. They include some of the earliest attested manuscripts of existing texts (such as the ' ...

as "macrobiotic hygiene" (2009). ''Changsheng'' is used in the Mawangdui medical manuscripts to designate "a somatic form of hygiene centering mainly on controlled breathing in conjunction with yogic exercises", comparable with the classical Greek gymnosophists

Gymnosophists ( grc, γυμνοσοφισταί, ''gymnosophistaí'', i.e. "naked philosophers" or "naked wise men" (from Greek γυμνός ''gymnós'' "naked" and σοφία ''sophía'' "wisdom")) is the name given by the Greeks to certain anc ...

(Collins and Kerr 2001: 14).

Historical developments

Information about ''yangsheng'' "nourishing life" health cultivation was traditionally limited to received texts including theChinese classics

Chinese classic texts or canonical texts () or simply dianji (典籍) refers to the Chinese texts which originated before the imperial unification by the Qin dynasty in 221 BC, particularly the "Four Books and Five Classics" of the Neo-Confucian ...

, until this corpus was augmented by some second-century BCE medical manuscripts discovered in the 1970s.

Han manuscripts

In

In Western Han dynasty

The Han dynasty (, ; ) was an imperial dynasty of China (202 BC – 9 AD, 25–220 AD), established by Liu Bang (Emperor Gao) and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by the short-lived Qin dynasty (221–207 BC) and a war ...

(202 BCE – 9 CE) tombs, Chinese archeologists excavated manuscript copies of ancient texts, some previously unknown, which included several historically important medical books that came to be known as the "medical manuals." Scribes

A scribe is a person who serves as a professional copyist, especially one who made copies of manuscripts before the invention of automatic printing.

The profession of the scribe, previously widespread across cultures, lost most of its promi ...

occasionally copied texts on valuable silk

Silk is a natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoons. The best-known silk is obtained from the coc ...

but usually on bamboo and wooden slips, which were the common media for writing documents in China before the widespread introduction of paper during the Eastern Han

The Han dynasty (, ; ) was an imperial dynasty of China (202 BC – 9 AD, 25–220 AD), established by Liu Bang (Emperor Gao) and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by the short-lived Qin dynasty (221–207 BC) and a warr ...

(25 BCE–220 CE). Fifteen medical manuscripts, among the Mawangdui Silk Texts The Mawangdui Silk Texts () are Chinese philosophical and medical works written on silk which were discovered at the Mawangdui site in Changsha, Hunan, in 1973. They include some of the earliest attested manuscripts of existing texts (such as the ' ...

, were excavated in 1973 at the Mawangdui archaeological site

An archaeological site is a place (or group of physical sites) in which evidence of past activity is preserved (either prehistoric or historic or contemporary), and which has been, or may be, investigated using the discipline of archaeology an ...

(modern Changsha

Changsha (; ; ; Changshanese pronunciation: (), Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is the capital and the largest city of Hunan Province of China. Changsha is the 17th most populous city in China with a population of over 10 million, an ...

, Hunan

Hunan (, ; ) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, part of the South Central China region. Located in the middle reaches of the Yangtze watershed, it borders the province-level divisions of Hubei to the north, Jiangxi to ...

). Two others, among the Zhangjiashan Han bamboo texts The Zhangjiashan Han bamboo texts are ancient Han Dynasty Chinese written works dated 196–186 BC. They were discovered in 1983 by archaeologists excavating tomb no. 247 at Mount Zhangjia () of Jiangling County, Hubei Province (near modern Jing ...

, were discovered in 1983 at Mount Zhangjia (張家山) (Jiangling County

Jiangling () is a county in southern Hubei province, People's Republic of China. Administratively, it is under the jurisdiction of Jingzhou City.

History

The county name derived from the old name of Jingzhou.

Liang dynasty Prince Xiao Yi 蕭繹 ( ...

, Hubei

Hubei (; ; alternately Hupeh) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, and is part of the Central China region. The name of the province means "north of the lake", referring to its position north of Dongting Lake. The prov ...

). Both locations were in the Han-era Changsha Kingdom

The Changsha Kingdom was a kingdom within the Han Empire of China, located in present-day Hunan and some surrounding areas. The kingdom was founded when Emperor Gaozu granted the territory to his follower Wu Rui in 203 or 202 BC, around the sa ...

(202 BCE-33 CE) (Engelhardt 2000: 85-86).

The Mawangdui manuscripts were found in a tomb dated 168 BCE, while Harper places the redaction of the manuscripts in the third century BCE (1998: 4). Six of the fifteen texts can be directly related to the ''yangsheng'' medical tradition of nourishing life. Two, the ''He yinyang'' (合陰陽, "Conjoining Yin and Yang") and the ''Tianxia zhidao tan'' (天下至道谈, "Discussion of the Perfect Way in All Under Heaven"), mainly focus on techniques of sexual cultivation. Two others, the ''Yangshengfang'' (養生方, "Recipes for Nourishing Life") and the ''Shiwen'' (十問, "Ten Questions"), similarly have sections on sexology, but also discuss breathing techniques, food therapies, and medicines (Harper 1998: 22-30). The ''Quegu shiqi'' (卻穀食氣, "The Rejection of Grains and Absorption of ''Qi'') deals mainly with techniques of eliminating grains and ordinary foodstuffs from the diet and replacing them with medicinal herbs and ''qi'' through special ''fuqi'' (服氣, "breath ingestion") exercises. The text repeatedly contrasts "those who eat ''qi''" with "those who eat grain" and explains this in cosmological terms, "Those who eat grain eat what is square; those who eat ''qi'' eat what is round. Round is heaven; square is earth." (tr. Harper 1998: 130). The ''Daoyin tu'' (導引圖, "Gymnastics Chart") above contains color illustrations of human figures performing therapeutic gymnastics. Some of the recognizable captions refer to the names of exercises, such as ''xiongjing'' (熊經, "bear hangs") and ''niaoshen'' (鳥伸, "bird stretches"), mentioned in the ''Zhuangzi'' and other texts below (Engelhardt 2000: 86).

The Zhangjiashan cache of manuscripts written on bamboo slips were excavated from a tomb dated 186 BCE, and contained two medical books. The '' Maishu'' (脈書, "Book on Meridians") comprises several texts that list ailments and describe the eleven (not modern twelve) meridian channels. The collection is closely related to the Mawangdui meridian texts and both briefly describe ''yangsheng'' practices of nourishing life. The ''Yinshu'' (引書, "Book on Pulling") outlines a daily and seasonal health regimen, including hygiene, dietetics, and sleeping; then it details fifty-seven preventative and curative gymnastic exercises, and massage techniques; and concludes with the etiology and the prevention of diseases. The text recommends various therapies, such as breathing exercises, bodily stretches, and careful treatment of the interior ''qi''. It says: "If you can pattern your ''qi'' properly and maintain your ''yin'' energy in fullness, then. the whole person will benefit". The ''Yinshu'' considered longevity techniques as limited to the aristocracy and upper classes, and makes a distinction between "upper class people" who fall ill owing to uncontrolled emotions such as extreme joy or rage, and less-fortunate individuals whose diseases tend to be caused by excessive labor, hunger, and thirst. Since the latter have no opportunity to learn the essential breathing exercises, they consequently become sick and die an early death. (Engelhardt 2000: 88). The ''Yinshu'' manuscript is the "earliest known systematized description of therapeutic exercise in China, and possibly anywhere in the world." (Yang 2022: 110).

Han texts

Classics from the

Classics from the Han dynasty

The Han dynasty (, ; ) was an imperial dynasty of China (202 BC – 9 AD, 25–220 AD), established by Liu Bang (Emperor Gao) and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by the short-lived Qin dynasty (221–207 BC) and a warr ...

(202 BCE-220 CE) first mentioned ''yangsheng'' techniques. The Daoist ''Zhuangzi'' has early descriptions of ''yangsheng'', notably Chapter 3 titled ''Yangsheng zhu'' (養生主, "Essentials for Nurturing Life"), which is in the pre-Han "Inner Chapters" attributed to Zhuang Zhou

Zhuang Zhou (), commonly known as Zhuangzi (; ; literally "Master Zhuang"; also rendered in the Wade–Giles romanization as Chuang Tzu), was an influential Chinese philosopher who lived around the 4th century BCE during the Warring States ...

(c. 369-286 BCE). In the fable about Lord Wenhui (文惠君) coming to understand the Dao while watching Cook Ding (庖丁) cut up an ox, he exclaims how wonderful it is "that skill can attain such heights!"

The cook replies, "What your servant loves is the Way, which goes beyond mere skill. When I first began to cut oxen, what I saw was nothing but whole oxen. After three years, I no longer saw whole oxen. Today, I meet the ox with my spirit rather than looking at it with my eyes. My sense organs stop functioning and my spirit moves as it pleases. In accord with the natural grain ��乎天理 I slice at the great crevices, lead the blade through the great cavities. Following its inherent structure, I never encounter the slightest obstacle even where the veins and arteries come together or where the ligaments and tendons join, much less from obvious big bones." ... " "Wonderful!" said Lord Wenhui. "From hearing the words of the cook, I have learned how to nourish life ��生" (3, tr. Mair 1994: 26-27)Two other ''Zhuangzi'' chapters mention ''yangsheng''. In the former context, Duke Wei (威公), the younger brother of

King Kao of Zhou

King Kao of Zhou (), alternatively King Kaozhe of Zhou (周考哲王), personal name Jī Wéi, was the thirty first king of the Chinese Zhou dynasty and the nineteenth of the Eastern Zhou. He reigned from 440 BC to 426 BC.

King Kao's father wa ...

(r. 440-426 BCE), asked Tian Kaizhi (田開之) what he had learned from his master Zhu Shen (祝腎, "Worthy Invoker"), who replied, "I have heard my master say, 'He who is good at nurturing life ��養生者is like a shepherd ��羊 If he sees one of his sheep lagging behind, he whips it forward'." In order to explain what this means, Tian contrasted a frugal Daoist hermit named Solitary Leopard (單豹) who lived in the cliffs, only drank water, and was healthy until the age of seventy when a tiger killed him, with a wealthy businessman named Chang Yi (張毅) who rushed about in search of profits, but died of typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several ...

at the age of forty. "Leopard nourished his inner being and the tiger ate his outer person. Yi nourished his outer person and sickness attacked his inner being. Both of them failed to whip their laggards forward." (19, tr. Mair 1994: 179).

This shepherding wordplay recalls the ancient characters for ''yang'' (養, "nourish"), such as 䍩 combining ''yáng'' (羊, "sheep") and ''pū'' (攵, "hit lightly; tap") denoting "shepherd; tend sheep", discussed above.

The latter story concerns the Lord of Lu (魯君) who heard that the Daoist Yan He (顏闔) had attained the Way and dispatched a messenger with presents for him. Yan "was waiting by a rustic village gate, wearing hempen clothing and feeding a cow by himself." When the messenger tried to convey the gifts, Yan said, "I'm afraid that you heard incorrectly and that the one who sent you with the presents will blame you. You had better check." The messenger went back to the ruler, and was told to return with the presents, but he could never again find Yan He, who disliked wealth and honor. "Judging from this, the achievements of emperors and kings are the leftover affairs of the sages, not that which fulfills the person or nourishes life ��身養生 Most of the worldly gentlemen of today endanger their persons and abandon life in their greed for things. Is this not sad?" (28, tr. Mair 1994: 287-288).

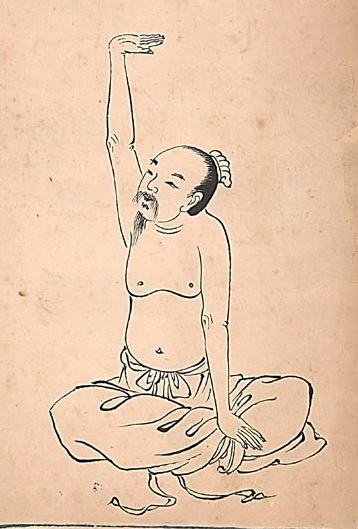

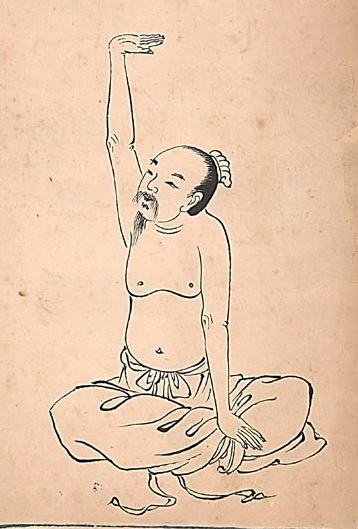

Three ''Zhuangzi'' chapters mention ''yangxing'' (養形, "nourishing the body"). One has the earliest Chinese reference to ways of controlling and regulating the breath (Engelhardt 2000: 101). It describes ''daoyin

Daoyin is a series of cognitive body and mind unity exercises practiced as a form of Taoist neigong, meditation and mindfulness to cultivate '' jing'' (essence) and direct and refine '' qi'', the internal energy of the body according to Traditio ...

'' ("guiding and pulling f ''qi'') calisthenics that typically involving bending, stretching, and mimicking animal movements (Despeux 2008: 1148).

Blowing and breathing, exhaling and inhaling, expelling the old and taking in the new, bear strides and bird stretches—all this is merely indicative of the desire for longevity. But it is favored by scholars who channel the vital breath and flex the muscles and joints, men who nourish the physical form ��形so as to emulate the hoary age of Progenitor P'eng. (15, tr. Mair 1994: 145).Although the ''Zhuangzi'' considers physical calisthenics inferior to more meditative techniques, this is a highly detailed description (Engelhardt 2000: 75). Another ''Zhuangzi'' chapter describes the limitations of ''yangxing'' (養形, "nourishing the body") (Maspero 1981: 420-421); "How sad that the people of the world think that nourishing the physical form ��形is sufficient to preserve life! But when it turns out that nourishing the physical form ��形s insufficient for the preservation of life, what in the world can be done that is sufficient?" (19, tr. Mair 1994: 174-175) The 139 BCE ''

Huainanzi

The ''Huainanzi'' is an ancient Chinese text that consists of a collection of essays that resulted from a series of scholarly debates held at the court of Liu An, Prince of Huainan, sometime before 139. The ''Huainanzi'' blends Daoist, Confuci ...

'' is an eclectic compilation, attributed to Liu An

Liú Ān (, c. 179–122 BC) was a Han dynasty Chinese prince, ruling the Huainan Kingdom, and an advisor to his nephew, Emperor Wu of Han (武帝). He is best known for editing the (139 BC) ''Huainanzi'' compendium of Daoist, Confucianist, an ...

, from various Hundred Schools of Thought

The Hundred Schools of Thought () were philosophies and schools that flourished from the 6th century BC to 221 BC during the Spring and Autumn period and the Warring States period of ancient China.

An era of substantial discrimination in China, ...

, especially Huang–Lao

''Huang–Lao'' or ''Huanglao'' () was the most influential Chinese school of thought in the early 2nd-century BCE Han dynasty, having its origins in a broader political-philosophical drive looking for solutions to strengthen the feudal order as ...

religious Daoism. ‘’Huainanzi’’ Chapter 7 echoes ‘’Zhuangzi’’ 15 disparaging ''yangsheng'' techniques because they require external supports.

If you huff and puff, exhale and inhale, blow out the old and pull in the new, practice the Bear Hang, the Bird Stretch, the Duck Splash, the Ape Leap, the Owl Gaze, and the Tiger Stare: This is what is practiced by those who nurture the body ��形 They are not the practices of those who polish the mind .g., the Perfected, 至人 They make their spirit overflow, without losing its fullness. When, day and night, without injury, they bring the spring to external things �� they unite with, and give birth to, the seasons in their own minds. (7.8, tr. Major 2010: 250).This criticism "gives a fascinating glimpse into the similarities", perceived even in the second century BCE, "between the ''qi'' cultivation practiced for physical benefits and the ''qi'' cultivation practiced for more transformative and deeply satisfying spiritual benefits, which seems to have involved more still sitting than active movement." (Major 2010: 236). The ''Huainanzi'' uses the term ''yangxing'' (養性, "nourishing one's inner nature") to denote mind-body techniques such as dietary regimens, breathing meditation, and macrobiotic yoga. "Since nature is the controlling mechanism of both consciousness and vitality, 'nourishing one's nature' produces both elevated states of consciousness and beneficial conditions of bodily health and longevity." (Major 2010: 907). For instance,

Tranquility and calmness are that by which the nature is nourished ��性 Harmony and vacuity are that by which Potency is nurtured ��德 When what is external does not disturb what is internal, then our nature attains what is suitable to it. When the harmony of nature is not disturbed, then Potency will rest securely in its position. Nurturing life ��生so as to order the age, embracing Potency so as to complete our years, this may be called being able to embody the Way. (2.13, Major 2010: 103).Another ''Huainanzi'' context compares five ''yang-'' "nourish; nurture" techniques.

In governing the self, it is best to nurture the spirit 'yangshen'' 養神 The next best is to nurture the body 'yangxing'' 養形 In governing the state, it is best to nurture transformation 'yanghua'' 養化 The next best is to correct the laws. A clear spirit and a balanced will, the hundred joints all in good order, constitute the root of nurturing vitality 'yangxing'' 養性 To fatten the muscles and skin, to fill the bowel and belly, to satiate the lusts and desires, constitute the branches of nurturing vitality 'yangsheng'' 養生” (20.18, tr. Major 2010: 815)The circa first century BCE ''

Huangdi Neijing

''Huangdi Neijing'' (), literally the ''Inner Canon of the Yellow Emperor'' or ''Esoteric Scripture of the Yellow Emperor'', is an ancient Chinese medical text or group of texts that has been treated as a fundamental doctrinal source for Chines ...

'' ("Inner Classic of the Yellow Emperor") discusses varied healing therapies, including medical acupuncture, moxibustion, and drugs as well as life-nourishing gymnastics, massages, and dietary regulation. The basic premise of longevity practices, which permeates the entire text "like a red thread", is to avoid diseases by maintaining the vital forces for as long as possible (Engelhardt 2000: 89). The ''Suwen'' (素問, "Basic Questions"), section echoes the early immortality cult, and says the ancient sages who regulated life in accordance with the Dao could easily live for a hundred years, yet complained that "these good times are over now, and people today do not know how to cultivate their life". (Engelhardt 2000: 90).

The astronomer, naturalist, and skeptical philosopher Wang Chong

Wang Chong (; 27 – c. 97 AD), courtesy name Zhongren (仲任), was a Chinese astronomer, meteorologist, naturalist, philosopher, and writer active during the Han Dynasty. He developed a rational, secular, naturalistic and mechanistic account ...

's c. 80 CE ''Lunheng

The ''Lunheng'', also known by numerous English translations, is a wide-ranging Chinese classic text by Wang Chong (27- ). First published in 80, it contains critical essays on natural science and Chinese mythology, philosophy, and literature ...

'' ("Critical Essays") criticizes many Daoist beliefs particularly ''yangxing'' (養性, "nourishing one's inner nature") (Despeux 2008: 1149). The ''Lunheng'' only uses ''yangsheng'' once; the "All About Ghosts" (訂鬼) chapter explains how heavenly '' qi'' (tr. "fluid") develops into ghosts and living organisms, "When the fluid is harmonious in itself, it produces and develops things [養生], when it is not, it does injury. First, it takes a form in heaven, then it descends, and becomes corporeal on earth. Hence, when ghosts appear, they are made of this stellar fluid." (tr. Forke 1907: 241).

Wang Chong's "Taoist Untruths" (道虛) chapter (tr. Forke 1907: 332-350) debunks several ''yangsheng'' practices, especially taking "immortality" drugs, Bigu (grain avoidance), ''bigu'' grain avoidance, and Daoist yogic breathing exercises.

Daoist ''waidan'' alchemists frequently compounded elixir of life, elixirs of "immortality", some of which contained lethal ingredients such as Mercury (element), mercury and arsenic that could cause Chinese alchemical elixir poisoning, elixir poisoning or death. One ''Lunheng'' anti-drug passage repeats the phrase ''tunyao yangxing'' (吞藥養性, "gulp down drugs and nourish one's nature") in a botanical example of natural aging.

The human hair and beard, and the different colours of things, when young and old, afford another cue. When a plant comes out, it has a green colour, when it ripens, it looks yellow. As long as man is young, his hair is black, when he grows old, it turns white. Yellow is the sign of maturity, white of old age. After a plant has become yellow, it may be watered and tended ever so much, it does not become green again. When the hair has turned white, no eating of drugs nor any care bestowed upon one’s nature [吞藥養性] can make it black again. Black and green do not come back, how could age and decrepitude be laid aside? ... Heaven in developing things can keep them vigorous up till autumn, but not further on till next spring. By swallowing drugs and nourishing one's nature [吞藥養性] one may get rid of sickness, but one cannot prolong one's life, and become an immortal. (tr. Forke 1907: 337).Admitting that while some medicines could improve one's health, Wang Chong denied that any could transform one into a Xian (Taoism), ''xian'' transcendent.

The Taoists sometimes use medicines [服食藥物] with a view to rendering their bodies more supple and their vital force stronger, hoping thus to prolong their years and to enter a new existence. This is a deception likewise. There are many examples that by the use of medicines the body grew more supple and the vital force stronger, but the world affords no instance of the prolongation of life and a new existence following. … The different physics cure all sorts of diseases. When they have been cured, the vital force is restored, and then the body becomes supple again. According to man’s original nature his body is supple of itself, and his vital force lasts long of its own accord. … Therefore, when by medicines the various diseases are dispelled, the body made supple, and the vital force prolonged, they merely return to their original state, but it is impossible to add to the number of years, let alone the transition into another existence. (tr. Forke 1907: 349).The "Taoist Untruths" chapter describes Daoist grain-free diets in terms of Bigu (grain avoidance), ''bigu'' (辟穀, "avoiding grains") and ''shiqi'' (食氣, "eat/ingest breath"). It says that Wangzi Qiao (王子喬), a son of King Ling of Zhou (571-545 BCE), practiced ''bigu'', as did Li Shaojun#Lunheng, Li Shaojun (fl. 133 BCE).

The idea prevails that those who abstain from eating grain [辟穀], are men well versed in the art of Tao. They say e.g., that [Wangzi Qiao] and the like, because they did not touch grain, and lived on different food than ordinary people, had not the same length of life as ordinary people, in so far as having passed a hundred years, they transcended into another state of being, and became immortals. That is another mistake. Eating and drinking are natural impulses, with which we are endowed at birth. Hence the upper part of the body has a mouth and teeth, the inferior part orifices. With the mouth and teeth one chews and eats, the orifices are for the discharge. Keeping in accord with one's nature, one follows the law of heaven, going against it, one violates one's natural propensities, and neglects one's natural spirit before heaven. How can one obtain long life in this way? … For a man not to eat is like not clothing the body. Clothes keep the skin warm, and food fills the stomach. With a warm epidermis and a well-filled belly the animal spirits are bright and exalted. If one is hungry, and has nothing to eat, or feels cold, and has nothing to warm one’s self, one may freeze or starve to death. How can frozen and starved people live longer than others? Moreover, during his life man draws his vital force from food, just as plants and trees do from earth. Pull out the roots of a plant or a tree, and separate them from the soil, and the plant will wither, and soon die. Shut a man's mouth, so that he cannot eat, and he will starve, but not be long-lived. (tr. Forke 1907: 347).Another passage describes ''shiqi'' (食氣, "eating/ingesting breath", tr. "eats the fluid") as a means to avoid eating grains.

The Taoists exalting each other's power assert that the Zhenren, "pure man" [真人] eats the fluid [食氣], that the fluid is his food. Wherefore the books say that the fluid-eaters live long, and do not die, that, although they do not feed on cereals, they become fat and strong by the fluid. This too is erroneous. What kind of fluid is understood by fluid? If fluid of the Yin and the Yang be meant, this fluid cannot satiate people. They may inhale this fluid, so that it fills their belly and bowels, yet they cannot feel satiated. If the fluid inherent in medicine be meant, man may use and eat a case full of dry drugs, or swallow some ten pills. But the effects of medicine are very strong. They cause great pain in the chest, but cannot feed a man. The meaning must certainly be that the fluid-eaters breathe, inhaling and exhaling, emitting the old air and taking in the new. Of old, Pengzu, P'êng Tsu used to practise this. Nevertheless he could not live indefinitely, but died of sickness. (tr. Forke 1907: 347-348).Besides ''shiqi'' ("eating ''qi''/breath") above, the ''Lunheng'' also refers to Daoist breath yoga as ''daoqi'' (導氣, "guide the ''qi''/breath").

Many Taoists hold that by regulating one's breath one can nourish one's nature [導氣養性], pass into another state of being, and become immortal. Their idea is that, if the blood vessels in the body be not always in motion, expanding and contracting, an obstruction ensues. There being no free passage, constipation is the consequence, which causes sickness and death. This is likewise without any foundation. Man’s body is like that of plants and trees. … When plants and trees, while growing, are violently shaken, they are injured, and pine away. Why then should man by drawing his breath and moving his body gain a long life and not die? The blood arteries traverse the body, as streams and rivers flow through the land. While thus flowing, the latter lose their limpidity, and become turbid. When the blood is moved, it becomes agitated also, which causes uneasiness. Uneasiness is like the hardships man has to endure without remedy. How can that be conducive to a long life? (tr. Forke 1907: 348-349).The Han Confucian moralist Xun Yue's (148-209) ''Shenjian'' (申鋻, Extended Reflections) has a viewpoint similar with Wang Chong's interpretation of cultivating the vital principle. One should seek moderation and harmony and avoid any excesses, and the breath should be circulated to avoid blocks and stagnation, just as the mythical Yu the Great did when he succeeded in quelling the flood waters (Despeux 2008: 1149).

Six Dynasties texts

During the Six Dynasties (222-589), ''yangsheng'' continued to develop and diversify in Daoist, ''Xuanxue'' ("Arcane Learning"), and medical circles. The polymath Ji Kang (223-262), one of the Daoist Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove, wrote a text titled ''Yangsheng lun'' (飬生論, "Essays on Nourishing Life"). The early ''Zhuangzi'' commentator Xiang Xiu (227-272) wrote a criticism with the same title, and Ji replied in his ''Danan Yangsheng lun'' (答難飬生論, "Answer to [Xiang Xiu's] Refutation of 'Essays on Nourishing Life'"). Ji Kang believed that achieving immortality was attainable, but only for those who have extraordinary ''qi'', yet even those without it who practice longevity techniques can achieve a lifespan of several hundred years (Engelhardt 2000: 90). The Daoist scholar Ge Hong's 318 CE ''Baopuzi'' ("Master Who Embraces Simplicity") describes many techniques of ''yangsheng'' (養生) and ''changsheng'' (長生, "longevity"), which Ware (1966) translates as "nurturing of life" and "fullness of life". Methods of ''neixiu'' (內修, "inner cultivation") include ''tuna'' (吐納, "breathing techniques"), ''taixi'' (胎息, "embryonic breath"), Daoyin, ''daoyin'' (導引, "gymnastics"), and ''xingqi'' (行氣, "circulation of breath/energy"), which are all old forms of what is today known as ''qigong'' (氣功). Methods of ''waiyang'' (外養, "outer nourishment") include ''xianyao'' (仙藥, "herbs of immortality"), Bigu (grain avoidance), ''bigu'' (辟穀, "avoiding grains"), Taoist sexual practices, ''fangzhongshu'' (房中術, "bedchamber arts"), ''jinzhou'' (禁咒, "curses and incantations"), and Fulu, ''fulu'' (符籙, "talismanic registers") (Theobald 2010). Ge Hong quotes the ''Huangdi jiuding shendan jing'' (黄帝九鼎神丹經, "The Yellow Emperor's Manual of the Nine-Vessel Magical Elixir").The Yellow Emperor rose into the sky and became a genie after taking this elixir. It adds that by merely doing the breathing exercises and calisthenics and taking herbal medicines one may extend one's years but cannot prevent ultimate death. Taking the divine elixir, however, will produce an interminable longevity and make one coeval with sky and earth; it lets one travel up and down in Paradise, riding clouds or driving dragons. (4, tr Ware 1966: 75)The ''Baopuzi'' makes a clear distinction between longevity and immortality, listing Xian (Taoism)#Baopuzi, three types of immortals: celestial (''tiānxiān'', 天仙), earthly (''dìxiān'', 地仙), and corpse-liberated (''shījiě xiān'', 尸解仙). Engelhardt says, "The foundation of immortality in any form, then, is a healthy life. This means that one must avoid all excesses and prevent or heal all diseases." Taking a fundamentally pragmatic position on ''yangsheng'' and ''changsheng'' practices, Ge Hong asserts that "the perfection of any one method can only be attained in conjunction with several others." (Engelhardt 2000: 77).

The taking of medicines [服藥] may be the first requirement for enjoying Fullness of Life [長生], but the concomitant practice of breath circulation [行氣] greatly enhances speedy attainment of the goal. Even if medicines [神藥] are not attainable and only breath circulation is practiced, a few hundred years will be attained provided the scheme is carried out fuIly, but one must also know the art of sexual intercourse [房中之術] to achieve such extra years. If ignorance of the sexual art causes frequent losses of sperm to occur, it will be difficult to have sufficient energy to circulate the breaths. (5, tr. Ware 1966, 105).There are inherent dangers for adepts who overspecialize in studying a particular technique.

In everything pertaining to the nurturing of life ��生one must learn much and make the essentials one's own; look widely and know how to select. There can be no reliance upon one particular specialty, for there is always the danger that breadwinners will emphasize their personal specialties. That is why those who know recipes for sexual intercourse [房中之術] say that only these recipes can lead to geniehood. Those who know breathing procedures [吐納] claim that only circulation of the breaths [行氣] can prolong our years. Those knowing methods for bending and stretching [屈伸] say that only calisthenics can exorcize old age. Those knowing herbal prescriptions [草木之方] say that only through the nibbling of medicines can one be free from exhaustion. Failures in the study of the divine process are due to such specializations. (6, tr. Ware 1966: 113).Ge Hong advises how to avoid illness.

If you are going to do everything possible to nurture your life [養生], you will take the divine medicines [神藥]. In addition, you will never weary of circulating your breaths [氣不]; morning and night you will do calisthenics [導引] to circulate your blood and breaths and see that they do not stagnate. In addition to these things, you will practice sexual intercourse in the right fashion; you will eat and drink moderately; you will avoid drafts and dampness; you will not trouble about things that are not within your competence. Do all these things, and you will not fall sick. (15, tr. Ware 1966: 252)The ''Baopuzi'' bibliography lists a no-longer extant ''Yangshengshu'' (養生書, "Book for Nurturing Life") in 105 ''juan'' (卷, "scrolls; fascicles; volumes") (Ware 1966: 383).

The Jin dynasty (266–420)#Eastern Jin (317–420), Eastern Jin dynasty official and ''Liezi'' commentator Zhang Zhan 張湛 (fl. 370) wrote one of the most influential works of the Six Dynasties period, the ''Yangsheng yaoji'' (養生要集, "Essentials of Nourishing Life"). For ''yangsheng'' health and immortality seekers, this text is said to be equally important as the ''Daodejing'' and ''Huangtingjing'' (黃庭經, "Yellow Court Classic"), it was "a widely available source of information for the educated but not necessarily initiated reader", until it was lost during the eighth century (Despeux 2008: 1149). The ''Yangsheng yaoji'' is important in the history of ''yangsheng'' techniques for three reasons: it cites from several earlier works that would have otherwise been lost, it presents a standard textbook model for many later works, and it is the earliest known text to systematize and classify the various longevity practices into one integrated system (Engelhardt 2000: 91). In the present day, the text survives in numerous fragments and citations, especially in the ''Yangxing yanming lu'' (養性延命錄, "On Nourishing Inner Nature and Extending Life"), ascribed to Tao Hongjing (456–536), Sun Simiao's 652 ''Qianjin fang'' (千金方, "Prescriptions Worth a Thousand Gold [Pieces]"), as well as in early Japanese medical texts such as the 984 ''Ishinpō'' ("Methods from the Heart of Medicine"). (Barrett and Kohn 2008: 1151).

During the Northern and Southern dynasties (420–589), ''yangsheng'' incorporated Chinese Buddhism, Chinese Buddhist meditation techniques (especially ''Ānāpānasati'' "mindfulness of breathing") and Indian gymnastic exercises. Daoist ''zuowang'' ("sitting and forgetting") and ''qingjing'' (清静, "clarity and stillness") meditating were influenced by Buddhist practices (Despeux 2008: 1149).

The Jin dynasty (266–420)#Eastern Jin (317–420), Eastern Jin dynasty official and ''Liezi'' commentator Zhang Zhan 張湛 (fl. 370) wrote one of the most influential works of the Six Dynasties period, the ''Yangsheng yaoji'' (養生要集, "Essentials of Nourishing Life"). For ''yangsheng'' health and immortality seekers, this text is said to be equally important as the ''Daodejing'' and ''Huangtingjing'' (黃庭經, "Yellow Court Classic"), it was "a widely available source of information for the educated but not necessarily initiated reader", until it was lost during the eighth century (Despeux 2008: 1149). The ''Yangsheng yaoji'' is important in the history of ''yangsheng'' techniques for three reasons: it cites from several earlier works that would have otherwise been lost, it presents a standard textbook model for many later works, and it is the earliest known text to systematize and classify the various longevity practices into one integrated system (Engelhardt 2000: 91). In the present day, the text survives in numerous fragments and citations, especially in the ''Yangxing yanming lu'' (養性延命錄, "On Nourishing Inner Nature and Extending Life"), ascribed to Tao Hongjing (456–536), Sun Simiao's 652 ''Qianjin fang'' (千金方, "Prescriptions Worth a Thousand Gold [Pieces]"), as well as in early Japanese medical texts such as the 984 ''Ishinpō'' ("Methods from the Heart of Medicine"). (Barrett and Kohn 2008: 1151).

During the Northern and Southern dynasties (420–589), ''yangsheng'' incorporated Chinese Buddhism, Chinese Buddhist meditation techniques (especially ''Ānāpānasati'' "mindfulness of breathing") and Indian gymnastic exercises. Daoist ''zuowang'' ("sitting and forgetting") and ''qingjing'' (清静, "clarity and stillness") meditating were influenced by Buddhist practices (Despeux 2008: 1149).

Sui to Tang texts

In the Sui dynasty, Sui (561-618) and Tang dynasty, Tang (618-907) dynasties, Daoist and medical circles transmitted essential ''yangsheng'' techniques for gymnastics and breathing (Despeux 2008: 1149). The number of medical texts increased significantly from 36 in the Yiwenzhi, Catalog of the Imperial Library of the Han to 256 in the Catalog of the Imperial Library of the Sui (Yang 2002: 111-112). The 610 ''Zhubing yuanhou lun'' (諸病源候論, "Treatise on the Origin and Symptoms of Diseases") was compiled upon imperial orders by an editorial committee supervised by the Sui physician and medical author Chao Yuanfang. This work is of "unprecedented scope", and the first systematic treatise on the etiology and pathology of Chinese medicine. It categorizes 1,739 diseases according to different causes and clinical symptoms, and most entries cite from an anonymous text titled ''Yangsheng fang'' (養生方, "Recipes for Nourishing Life"), which closely resembles the fourth-century ''Yangsheng yaoji''. The ''Zhubing yuanhou lun'' does not prescribe standard herbal or acupuncture therapies for clinical cases but rather specific ''yangxing'' (養性) techniques of hygienic measures, diets, gymnastics, massages, breathing, and visualization (Engelhardt 2000: 79, 91-92). The famous physician Sun Simiao devoted two chapters (26 "Dietetics" and 27 "Longevity Techniques") of his 652 ''Qianjin fang'' (千金方, "Prescriptions Worth a Thousand Gold [Pieces]", see above) to life-nourishing methods. The ''Qianjin fang'' is a huge compendium of all medical knowledge in the Tang period, the oldest source on Chinese therapeutics that has survived in its entirety, and is still being used to train traditional physicians today (Engelhardt 2000: 93). Sun also wrote the ''Sheyang zhenzhong fang'' (攝養枕中方, "Pillow Book of Methods for Nourishing Life") is divided into five parts: prudence, prohibitions, ''daoyin'' gymnastics, guiding the ''qi'', and Taoist meditation#Other key words, guarding the One (''shouyi'' 守一). The text identifies overindulgence of any sort as the main reason for illness. (Engelhardt 1989: 280, 294). Some shorter texts are also attributed to Sun Simiao, including the ''Yangxing yanming lu'' (養性延命錄, "On Nourishing Inner Nature and Extending Life"), the ''Fushou lun'' (福壽論, "Essay on Happiness and Longevity"), and the ''Baosheng ming'' (保生銘, "Inscription on Protecting Life") (Despeux 2008: 1150). The Daoist Shangqing School patriarch Sima Chengzhen (司馬承禎, 647-735) composed the 730 ''Fuqi jingyi lun'' (服氣精義論, "Essay on the Essential Meaning of Breath Ingestion"), which presented integrated outlines of health practices, with both traditional Chinese physical techniques and the Buddhist-inspired practice of Taoist meditation#Types of meditation, ''guan'' (觀, "insight meditation"), as preliminaries for the attainment and realization or the Dao (Engelhardt 2000: 80). The work relies on both Shangqing religious sources and major medical references such as the ''Huangdi Neijing

''Huangdi Neijing'' (), literally the ''Inner Canon of the Yellow Emperor'' or ''Esoteric Scripture of the Yellow Emperor'', is an ancient Chinese medical text or group of texts that has been treated as a fundamental doctrinal source for Chines ...

'', and groups all the various longevity techniques around the central notion or absorbing ''qi''. The practical instructions on specific exercises are supplemented by theoretical medical knowledge, such as the Zang-fu#Zang, five orbs, healing of diseases, and awareness of symptoms. (Engelhardt 2000: 93).

Song to Qing texts

''Yangsheng'' practices underwent significant changes from the Song dynasty (960-1279) onward. They integrated many elements drawn from ''neidan'' ("inner alchemy") practices, and aroused the interest of scholars. For the Song dynasty alone, there are about twenty books on the subject. An important author of the time was Zhou Shouzhong (周守中), who wrote the ''Yangsheng leizuan'' (養生類纂, "Classified Compendium on Nourishing Life"), the ''Yangsheng yuelan'' (養生月覽, "Monthly Readings on Nourishing Life"), and other books (Despeux 2008: 1150). Famous Song Scholar-official, literati and poets, such as Su Shi (1007-1072) and Su Dongpo (1037-1101), wrote extensively about their longevity practices. The Song author Chen Zhi's (陳直) ''Yanglao Fengqin Shu'' (養老奉親書, "Book on Nourishing Old Age and Taking Care of One's Parents") was the first Chinese work dealing exclusively with geriatrics (Engelhardt 2000: 81). Along the development of Neo-Confucianism and the growth of syncretism among Daoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism in the Ming dynasty, Ming (1368–1644) and Qing dynasty, Qing (1636–1912) periods, a number of ethical elements were incorporated into ''yangsheng'' (Despeux 2008: 1150).

During the Ming period, various collections and compendia of longevity writings appeared. Hu Wenhuan (胡文焕), editor of the 1639 edition ''Jiuhuang Bencao'' ("Famine Relief Herbal"), wrote the main work on ''yangsheng'', the c. 1596 ''Shouyang congshu'' (壽養叢書, "Collectanea on Longevity and Nourishment [of Life]"), which includes the ''Yangsheng shiji'' (養生食忌, "Prohibitions on Food for Nourishing Life") and the ''Yangsheng daoyin fa'' (養生導引法, "''Daoyin'' Methods for Nourishing Life"). Some works are inclusive treatments of diverse longevity techniques, for example, the dramatist Gao Lian (dramatist), Gao Lian's (fl. 1573-1581) ''Zunsheng bajian'' (遵生八笺, "Eight Essays on Being in Accord with Life") described ''yangsheng'' diets, breathing methods, and medicines. Other works focus entirely on a single method, such as ''Tiaoxi fa'' (調息法, "Breath Regulation Methods") by the Neo-Confucian philosopher Wang Ji (philosopher), Wang Ji (1498-1582) (Engelhardt 2000: 81). Another new development under the Ming is the increased integration and legitimization of ''yangsheng'' techniques into medical literature. For example, Yang Jizhou's (楊繼洲) extensive 1601 ''Zhenjiu dacheng'' (針灸大成, "Great Compendium on Acupuncture and Moxibustion"), which remains a classic to the present day, presents gymnastic exercises for the various ''qi''-Meridian (Chinese medicine), meridians (Engelhardt 2000: 82).

Unlike the Ming dynasty, the Qing dynasty produced no important work on ''yangsheng''. In the twentieth century, ''yangsheng'' evolved into the modern Westernized science of ''weisheng'' (衛生, "hygiene, health, sanitation") on the one hand, and into ''qigong'' on the other (Despeux 2008: 1150).

Dear's anthropological study of ''yangsghengs popularity and commercialization in early twenty-first century China makes a contrast with Qigong fever, ''Qigong'' fever, a 1980s and 1990s Chinese social phenomenon in which the practice of ''qigong'' rose to extraordinary popularity, estimated to have reached a peak number of practitioners between 60 and 200 million. While the Qigong fever had a "somewhat austere and Salvationist aspect", the more recent Yangsheng fever, "which covers so much of the same ground in the quest for health and identity, has a certain low-key decadence about it." For instance, using the term ''yangsheng'' to advertise deluxe villas in the suburbs, luxury health spas, extravagantly packaged expensive medicines like ''chongcao'' (蟲草, ''Ophiocordyceps sinensis''), and tourism to naturally beautiful landscapes, "are some of the markers of the new ''Yangsheng''." (Dear 2012: 29).

''Yangsheng'' practices underwent significant changes from the Song dynasty (960-1279) onward. They integrated many elements drawn from ''neidan'' ("inner alchemy") practices, and aroused the interest of scholars. For the Song dynasty alone, there are about twenty books on the subject. An important author of the time was Zhou Shouzhong (周守中), who wrote the ''Yangsheng leizuan'' (養生類纂, "Classified Compendium on Nourishing Life"), the ''Yangsheng yuelan'' (養生月覽, "Monthly Readings on Nourishing Life"), and other books (Despeux 2008: 1150). Famous Song Scholar-official, literati and poets, such as Su Shi (1007-1072) and Su Dongpo (1037-1101), wrote extensively about their longevity practices. The Song author Chen Zhi's (陳直) ''Yanglao Fengqin Shu'' (養老奉親書, "Book on Nourishing Old Age and Taking Care of One's Parents") was the first Chinese work dealing exclusively with geriatrics (Engelhardt 2000: 81). Along the development of Neo-Confucianism and the growth of syncretism among Daoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism in the Ming dynasty, Ming (1368–1644) and Qing dynasty, Qing (1636–1912) periods, a number of ethical elements were incorporated into ''yangsheng'' (Despeux 2008: 1150).

During the Ming period, various collections and compendia of longevity writings appeared. Hu Wenhuan (胡文焕), editor of the 1639 edition ''Jiuhuang Bencao'' ("Famine Relief Herbal"), wrote the main work on ''yangsheng'', the c. 1596 ''Shouyang congshu'' (壽養叢書, "Collectanea on Longevity and Nourishment [of Life]"), which includes the ''Yangsheng shiji'' (養生食忌, "Prohibitions on Food for Nourishing Life") and the ''Yangsheng daoyin fa'' (養生導引法, "''Daoyin'' Methods for Nourishing Life"). Some works are inclusive treatments of diverse longevity techniques, for example, the dramatist Gao Lian (dramatist), Gao Lian's (fl. 1573-1581) ''Zunsheng bajian'' (遵生八笺, "Eight Essays on Being in Accord with Life") described ''yangsheng'' diets, breathing methods, and medicines. Other works focus entirely on a single method, such as ''Tiaoxi fa'' (調息法, "Breath Regulation Methods") by the Neo-Confucian philosopher Wang Ji (philosopher), Wang Ji (1498-1582) (Engelhardt 2000: 81). Another new development under the Ming is the increased integration and legitimization of ''yangsheng'' techniques into medical literature. For example, Yang Jizhou's (楊繼洲) extensive 1601 ''Zhenjiu dacheng'' (針灸大成, "Great Compendium on Acupuncture and Moxibustion"), which remains a classic to the present day, presents gymnastic exercises for the various ''qi''-Meridian (Chinese medicine), meridians (Engelhardt 2000: 82).

Unlike the Ming dynasty, the Qing dynasty produced no important work on ''yangsheng''. In the twentieth century, ''yangsheng'' evolved into the modern Westernized science of ''weisheng'' (衛生, "hygiene, health, sanitation") on the one hand, and into ''qigong'' on the other (Despeux 2008: 1150).

Dear's anthropological study of ''yangsghengs popularity and commercialization in early twenty-first century China makes a contrast with Qigong fever, ''Qigong'' fever, a 1980s and 1990s Chinese social phenomenon in which the practice of ''qigong'' rose to extraordinary popularity, estimated to have reached a peak number of practitioners between 60 and 200 million. While the Qigong fever had a "somewhat austere and Salvationist aspect", the more recent Yangsheng fever, "which covers so much of the same ground in the quest for health and identity, has a certain low-key decadence about it." For instance, using the term ''yangsheng'' to advertise deluxe villas in the suburbs, luxury health spas, extravagantly packaged expensive medicines like ''chongcao'' (蟲草, ''Ophiocordyceps sinensis''), and tourism to naturally beautiful landscapes, "are some of the markers of the new ''Yangsheng''." (Dear 2012: 29).

References

*Barrett, T.H. and Livia Kohn (2008), "''Yangsheng yaoji''", in Fabrizio Pregadio, ed., ''The Encyclopedia of Taoism'', Routledge, 1151-1152. *Collins, Roy and David Kerr (2001)Etymology of the Word “Macrobiotic:s”[''sic''

and Its Use in Modern Chinese Scholarship], ''Sino-Platonic Papers'' 113. *Dear, David (2012),

Chinese Yangsheng: Self-help and Self-image

, ''Asian Medicine'' 7: 1-33. *DeFrancis, John, genl. ed. (1996), ''ABC Chinese-English Dictionary'', University of Hawaii Press. *Despeux, Catherine (2008), "Yangsheng 養生 Nourishing Life", in Fabrizio Pregadio, ed., ''The Encyclopedia of Taoism'', Routledge, 1148-1150. *Engelhardt, Ute (1989), "Qi for Life: Longevity in the Tang," in Kohn (1989) ''Taoist Meditation and Longevity Techniques'', University of Michigan, 263-96. *Engelhardt, Ute (2000), "Longevity Techniques and Chinese Medicine," in Kohn ''Daoism Handbook'', E. J. Brill, 74-108. *Forke, Alfred, tr. (1907)

Lun-hêng, Part 1, Philosophical Essays of Wang Ch'ung

Harrassowitz. *Harper, Donald (1998, 2009), ''Early Chinese Medical Literature: The Mawangdui Medical Manuscripts'', Kegan Paul. *Kohn, Livia, ed. (1989), ''Taoist Meditation and Longevity Techniques'', University of Michigan. *Lau, D. C. (1970)

''Mencius''

Penguin Books. *Mair, Victor H., tr. (1994), ''Wandering on the Way, Early Taoist Tales and Parables of Chuang Tzu'', Bantam. *Mair, Victor H. (2007), ''The Art of War: Sun Zi's Military Method'', Columbia University Press. *Major, John S., Sarah Queen, Andrew Meyer, and Harold D. Roth (2010), ''The Huainanzi: A Guide to the Theory and Practice of Government in Early Han China'', Columbia University Press. *Maspero, Henri (1981), ''Taoism and Chinese Religion'', tr. by Frank A. Kierman, University of Massachusetts Press. *Needham, Joseph and Lu Gwei-djen (1974), ''Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 5 Chemistry and Chemical Technology Part 2: Spagyrical Discovery and Inventions: Magisteries of Gold and Immortality'', Cambridge University Press. *Needham, Joseph and Lu Gwei-djen (2000), ''Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 6, Biology and Biological Technology, Part VI: Medicine'', Cambridge University Press. *Theobald, Ulrich (2010), "Baopuzi 抱朴子", Chinaknowledge. *Ware, James R., tr. (1966), ''Alchemy, Medicine and Religion in the China of A.D. 320: The'' Nei Pien'' of Ko Hung'', Dover. *Yang, Dolly (2022), "Therapeutic Exercise in the Medical Practice of Sui China (581-618 CE)", in ''Routledge Handbook of Chinese Medicine'', ed. by Vivienne Lo, Michael Stanley-Baker, and Dolly Yang, 109-119, Routledge.

External links

Daoist Health Cultivation

FYSK: Daoist Culture Centre, 19 September 2009 {{Traditional Chinese medicine Life extension Meditation Taoist practices Traditional Chinese medicine