Xinwei Expressway on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The sexagenary cycle, also known as the Stems-and-Branches or ganzhi ( zh, 干支, gānzhī), is a cycle of sixty terms, each corresponding to one year, thus a total of sixty years for one cycle, historically used for recording time in China and the rest of the East Asian cultural sphere. It appears as a means of recording days in the first Chinese written texts, the Shang dynasty, Shang oracle bones of the late second millennium BC. Its use to record years began around the middle of the 3rd century BC. The cycle and its variations have been an important part of the traditional calendrical systems in Chinese-influenced Asian states and territories, particularly those of Japanese calendar, Japan, Korean calendar, Korea, and Vietnamese calendar, Vietnam, with the old Chinese system still in use in Taiwanese calendar, Taiwan, and to a lesser extent, in Mainland China.

This traditional method of numbering days and years no longer has any significant role in modern Chinese time-keeping or the official calendar. However, the sexagenary cycle is used in the names of many historical events, such as the Chinese Xinhai Revolution, the Japanese Boshin War, the Korean Imjin War and the Vietnamese Tet Offensive, Tet Mau Than. It also continues to have a role in contemporary Chinese astrology and Chinese fortune telling, fortune telling. There are some parallels in this with the current 60-year cycle of the Samvatsara, Hindu calendar.

Each term in the sexagenary cycle consists of two Chinese characters, the first being one of the ten Heavenly Stems of the Chinese ten-day week, Shang-era week and the second being one of the twelve Earthly Branches representing the years of Jupiter (planet), Jupiter's wikt:duodecennial, duodecennial orbital cycle. The first term ''jiǎzǐ'' () combines the first heavenly stem with the first earthly branch. The second term ''yǐchǒu'' () combines the second stem with the second branch. This pattern continues until both cycles conclude simultaneously with ''guǐhài'' (), after which it begins again at ''jiǎzǐ''. This termination at ten and twelve's least common multiple leaves half of the combinations—such as ''jiǎchǒu'' ()—unused; this is traditionally explained by reference to pairing the stems and branches according to their yin and yang properties.

This combination of two sub-cycles to generate a larger cycle and its use to record time have parallels in other calendrical systems, notably the Akan calendar.

Each term in the sexagenary cycle consists of two Chinese characters, the first being one of the ten Heavenly Stems of the Chinese ten-day week, Shang-era week and the second being one of the twelve Earthly Branches representing the years of Jupiter (planet), Jupiter's wikt:duodecennial, duodecennial orbital cycle. The first term ''jiǎzǐ'' () combines the first heavenly stem with the first earthly branch. The second term ''yǐchǒu'' () combines the second stem with the second branch. This pattern continues until both cycles conclude simultaneously with ''guǐhài'' (), after which it begins again at ''jiǎzǐ''. This termination at ten and twelve's least common multiple leaves half of the combinations—such as ''jiǎchǒu'' ()—unused; this is traditionally explained by reference to pairing the stems and branches according to their yin and yang properties.

This combination of two sub-cycles to generate a larger cycle and its use to record time have parallels in other calendrical systems, notably the Akan calendar.

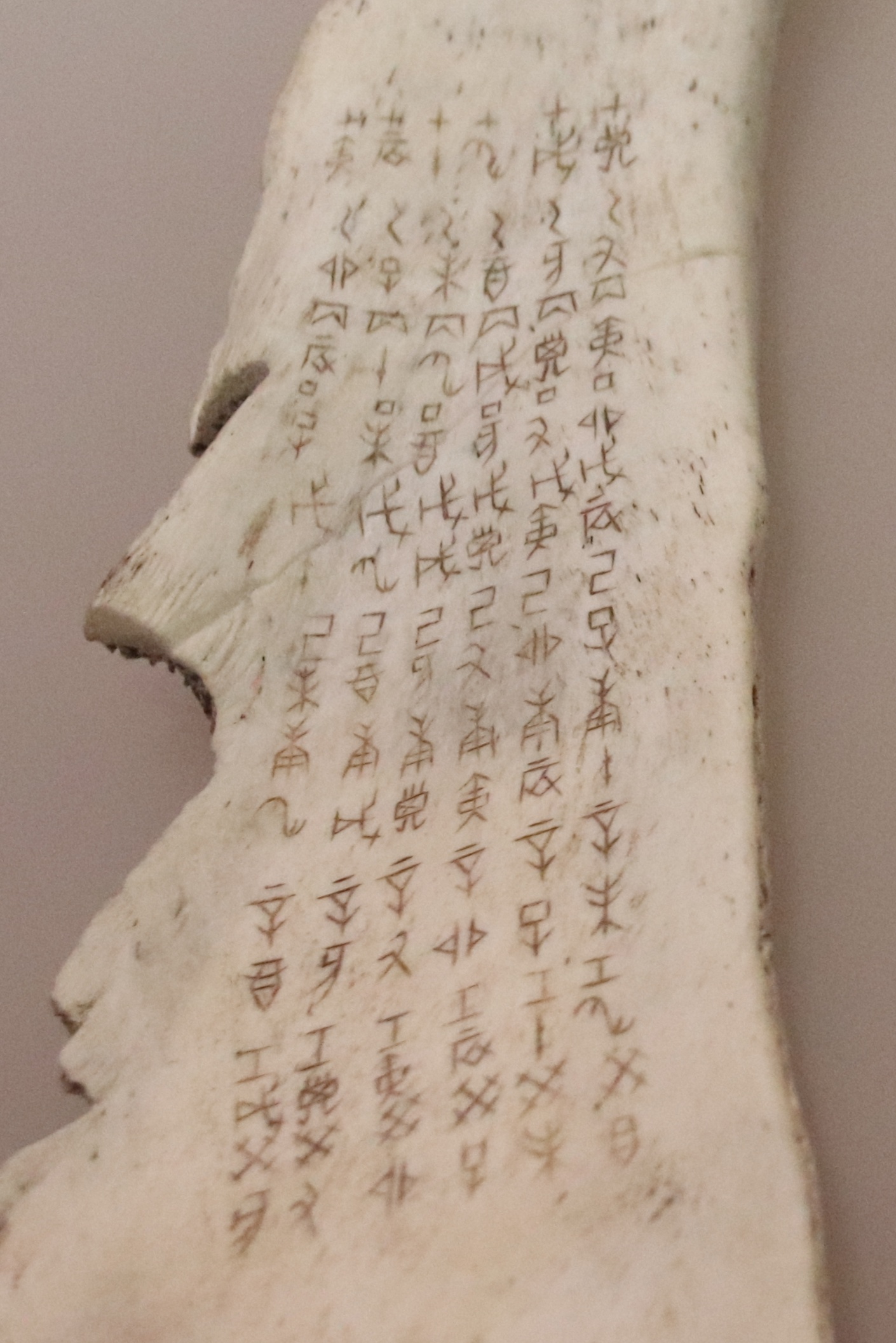

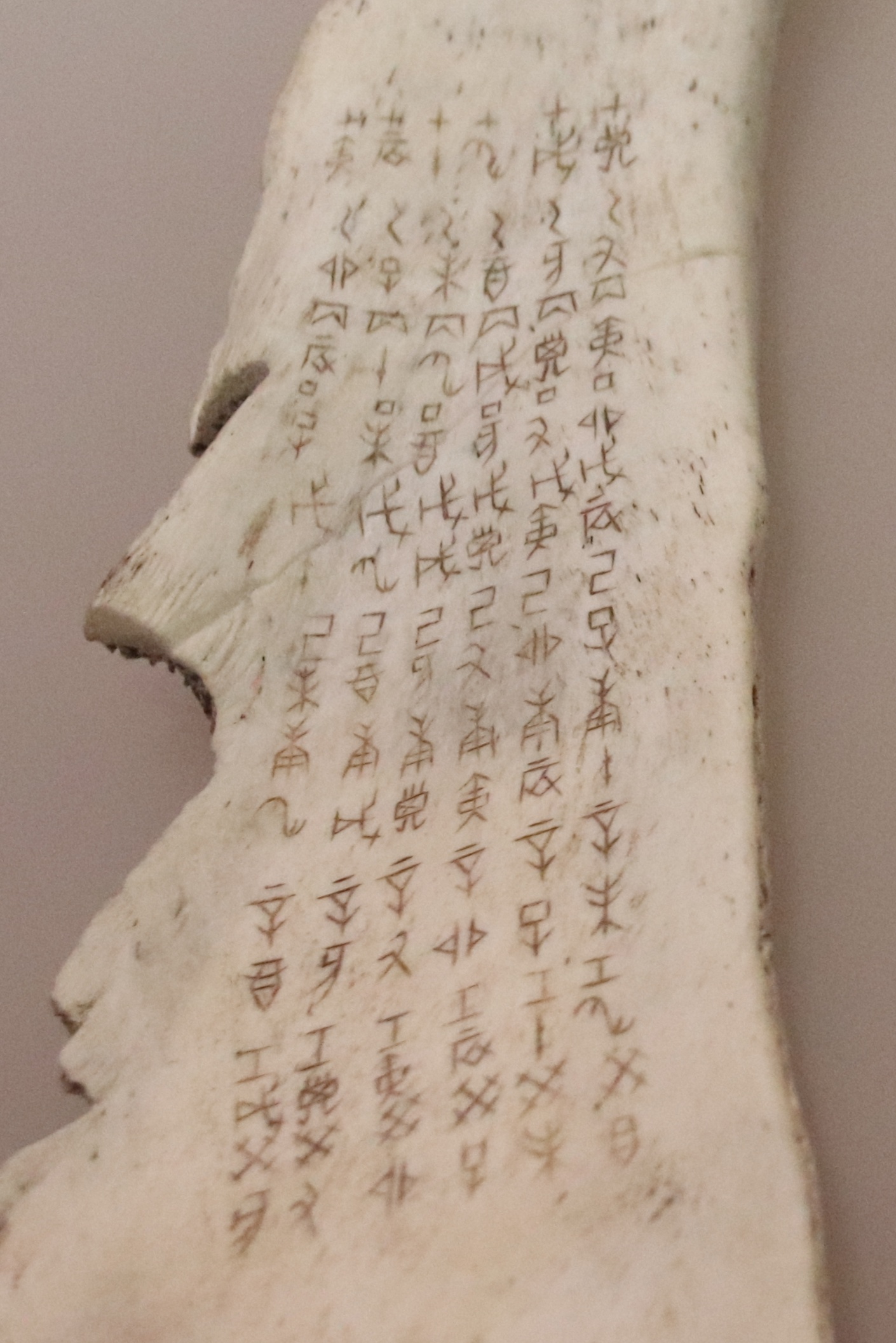

The sexagenary cycle is attested as a method of recording days from the earliest written records in China, oracle bone inscriptions, records of divination on oracle bones, beginning ca. 1100 BC. Almost every oracle bone inscription includes a date in this format. This use of the cycle for days is attested throughout the Zhou dynasty and remained common into the Han dynasty, Han period for all documentary purposes that required dates specified to the day.

Almost all the dates in the ''Spring and Autumn Annals'', a chronological list of events from 722 to 481 BC, use this system in combination with regnal years and months (lunations) to record dates. Eclipses recorded in the Annals demonstrate that continuity in the sexagenary day-count was unbroken from that period onwards. It is likely that this unbroken continuity went back still further to the first appearance of the sexagenary cycle during the Shang period.

The use of the sexagenary cycle for recording years is much more recent. The earliest discovered documents showing this usage are among the silk manuscripts recovered from Mawangdui, Mawangdui tomb 3, sealed in 168 BC. In one of these documents, a sexagenary grid diagram is annotated in three places to mark notable events. For example, the first year of the reign of Qin Shi Huang (), 246 BC, is noted on the diagram next to the position of the 60-cycle term ''yǐ-mǎo'' (, 52 of 60), corresponding to that year. Use of the cycle to record years became widespread for administrative time-keeping during the Western Han dynasty (202 BC – 8 AD). The count of years has continued uninterrupted ever since: the year 1984 began the present cycle (a —''jiǎ-zǐ'' year), and 2044 will begin another. Note that in China the new year, when the sexagenary count increments, is not January 1, but rather the Chinese new year, lunar new year of the traditional Chinese calendar. For example, the ji-chou year (coinciding roughly with 2009) began on January 26, 2009. (However, for astrology, the year begins with the first solar term "Lìchūn" (), which occurs near February 4.)

In Japan, according to ''Nihon shoki'', the calendar was transmitted to Japan in 553. But it was not until the Empress Suiko, Suiko era that the calendar was used for politics. The year 604, when the Japanese officially adopted the Chinese calendar, was the first year of the cycle.

The Korean ( hwangap) and Japanese tradition ( ''kanreki'') of celebrating the 60th birthday (literally 'return of calendar') reflects the influence of the sexagenary cycle as a count of years.

The Tibetan calendar also counts years using a 60-year cycle based on 12 animals and 5 elements, but while the first year of the Chinese cycle is always the year of the Wood Rat (zodiac), Rat, the first year of the Tibetan cycle is the year of the Fire Rabbit (zodiac), Rabbit (—''dīng-mǎo'', year 4 on the Chinese cycle).

The sexagenary cycle is attested as a method of recording days from the earliest written records in China, oracle bone inscriptions, records of divination on oracle bones, beginning ca. 1100 BC. Almost every oracle bone inscription includes a date in this format. This use of the cycle for days is attested throughout the Zhou dynasty and remained common into the Han dynasty, Han period for all documentary purposes that required dates specified to the day.

Almost all the dates in the ''Spring and Autumn Annals'', a chronological list of events from 722 to 481 BC, use this system in combination with regnal years and months (lunations) to record dates. Eclipses recorded in the Annals demonstrate that continuity in the sexagenary day-count was unbroken from that period onwards. It is likely that this unbroken continuity went back still further to the first appearance of the sexagenary cycle during the Shang period.

The use of the sexagenary cycle for recording years is much more recent. The earliest discovered documents showing this usage are among the silk manuscripts recovered from Mawangdui, Mawangdui tomb 3, sealed in 168 BC. In one of these documents, a sexagenary grid diagram is annotated in three places to mark notable events. For example, the first year of the reign of Qin Shi Huang (), 246 BC, is noted on the diagram next to the position of the 60-cycle term ''yǐ-mǎo'' (, 52 of 60), corresponding to that year. Use of the cycle to record years became widespread for administrative time-keeping during the Western Han dynasty (202 BC – 8 AD). The count of years has continued uninterrupted ever since: the year 1984 began the present cycle (a —''jiǎ-zǐ'' year), and 2044 will begin another. Note that in China the new year, when the sexagenary count increments, is not January 1, but rather the Chinese new year, lunar new year of the traditional Chinese calendar. For example, the ji-chou year (coinciding roughly with 2009) began on January 26, 2009. (However, for astrology, the year begins with the first solar term "Lìchūn" (), which occurs near February 4.)

In Japan, according to ''Nihon shoki'', the calendar was transmitted to Japan in 553. But it was not until the Empress Suiko, Suiko era that the calendar was used for politics. The year 604, when the Japanese officially adopted the Chinese calendar, was the first year of the cycle.

The Korean ( hwangap) and Japanese tradition ( ''kanreki'') of celebrating the 60th birthday (literally 'return of calendar') reflects the influence of the sexagenary cycle as a count of years.

The Tibetan calendar also counts years using a 60-year cycle based on 12 animals and 5 elements, but while the first year of the Chinese cycle is always the year of the Wood Rat (zodiac), Rat, the first year of the Tibetan cycle is the year of the Fire Rabbit (zodiac), Rabbit (—''dīng-mǎo'', year 4 on the Chinese cycle).

* The names of several animals can be translated into English in several different ways. The Vietnamese Earthly Branches use cat instead of Rabbit (zodiac), Rabbit.

As mentioned above, the cycle first started to be used for indicating years during the Han dynasty, but it also can be used to indicate earlier years retroactively. Since it repeats, by itself it cannot specify a year without some other information, but it is frequently used with the Chinese era name (年号; "niánhào") to specify a year. The year starts with the new year of whoever is using the calendar. In China, the cyclic year normally changes on the Chinese Lunar New Year. In Japan until recently it was the Japanese lunar new year, which was sometimes different from the Chinese; now it is January 1. So when calculating the cyclic year of a date in the Gregorian year, one has to consider what their "new year" is. Hence, the following calculation deals with the Chinese dates ''after'' the Lunar New Year in that Gregorian year; to find the corresponding sexagenary year in the dates before the Lunar New Year would require the Gregorian year to be decreased by 1.

As for example, the year 2697 BC (or −2696, using the astronomical year count), traditionally the first year of the reign of the legendary Yellow Emperor, was the first year (甲子; ''jiǎ-zǐ'') of a cycle. 2700 years later in 4 AD, the duration equivalent to 45 60-year cycles, was also the starting year of a 60-year cycle. Similarly 1980 years later, 1984 was the start of a new cycle.

Thus, to find out the Gregorian calendar, Gregorian year's equivalent in the sexagenary cycle use the appropriate method below.

# For any year number greater than 4 AD, the equivalent sexagenary year can be found by subtracting 3 from the Gregorian year, dividing by 60 and taking the remainder. See example below.

# For any year before 1 AD, the equivalent sexagenary year can be found by adding 2 to the Gregorian year number (in BC), dividing it by 60, and subtracting the remainder from 60.

# 1 AD, 2 AD and 3 AD correspond respectively to the 58th, 59th and 60th years of the sexagenary cycle.

#The formula for years AD is (year – 3 or + 57) mod 60 and for years BC is 60 – (year + 2) mod 60.

The result will produce a number between 0 and 59, corresponding to the year order in the cycle; if the remainder is 0, it corresponds to the 60th year of a cycle. Thus, using the first method, the equivalent sexagenary year for 2012 AD is the 29th year (壬辰; ''rén-chén''), as ''(2012–3) modulo operation, mod 60 = 29'' (i.e., the remainder of (2012–3) divided by 60 is 29). Using the second, the equivalent sexagenary year for 221 BC is the 17th year (庚辰; ''gēng-chén''), as ''60- [(221+2) mod 60] = 17'' (i.e., 60 minus the remainder of (221+2) divided by 60 is 17).

As mentioned above, the cycle first started to be used for indicating years during the Han dynasty, but it also can be used to indicate earlier years retroactively. Since it repeats, by itself it cannot specify a year without some other information, but it is frequently used with the Chinese era name (年号; "niánhào") to specify a year. The year starts with the new year of whoever is using the calendar. In China, the cyclic year normally changes on the Chinese Lunar New Year. In Japan until recently it was the Japanese lunar new year, which was sometimes different from the Chinese; now it is January 1. So when calculating the cyclic year of a date in the Gregorian year, one has to consider what their "new year" is. Hence, the following calculation deals with the Chinese dates ''after'' the Lunar New Year in that Gregorian year; to find the corresponding sexagenary year in the dates before the Lunar New Year would require the Gregorian year to be decreased by 1.

As for example, the year 2697 BC (or −2696, using the astronomical year count), traditionally the first year of the reign of the legendary Yellow Emperor, was the first year (甲子; ''jiǎ-zǐ'') of a cycle. 2700 years later in 4 AD, the duration equivalent to 45 60-year cycles, was also the starting year of a 60-year cycle. Similarly 1980 years later, 1984 was the start of a new cycle.

Thus, to find out the Gregorian calendar, Gregorian year's equivalent in the sexagenary cycle use the appropriate method below.

# For any year number greater than 4 AD, the equivalent sexagenary year can be found by subtracting 3 from the Gregorian year, dividing by 60 and taking the remainder. See example below.

# For any year before 1 AD, the equivalent sexagenary year can be found by adding 2 to the Gregorian year number (in BC), dividing it by 60, and subtracting the remainder from 60.

# 1 AD, 2 AD and 3 AD correspond respectively to the 58th, 59th and 60th years of the sexagenary cycle.

#The formula for years AD is (year – 3 or + 57) mod 60 and for years BC is 60 – (year + 2) mod 60.

The result will produce a number between 0 and 59, corresponding to the year order in the cycle; if the remainder is 0, it corresponds to the 60th year of a cycle. Thus, using the first method, the equivalent sexagenary year for 2012 AD is the 29th year (壬辰; ''rén-chén''), as ''(2012–3) modulo operation, mod 60 = 29'' (i.e., the remainder of (2012–3) divided by 60 is 29). Using the second, the equivalent sexagenary year for 221 BC is the 17th year (庚辰; ''gēng-chén''), as ''60- [(221+2) mod 60] = 17'' (i.e., 60 minus the remainder of (221+2) divided by 60 is 17).

for Jan or Feb in a common year and in a leap year. *Stem-branch for February 22, 720 BC (−719). :y = 5 x (720–719) + [1/4] = 5 :c = 8 :m = 30 + [0.6 x 15 – 3] – 5 = 31 :d = 22 :SB = 5 + 8 + 31 + 22 – 60 = 6 :S = B = 6, 己巳 *Stem-branch for November 1, 211 BC (−210). :y = 5 x (240–210) + [30/4] = 5 x 6 + 7 = 37 :c = 8 :m = 0 + [0.6 x 12 – 3] = 4 :d = 1 :SB = 37 + 8 + 4 + 1 = 50 :S = 0, B = 2, 癸丑 *Stem-branch for February 18, 1912. :y = 5 x (1912–1920) + [-8/4] + 60 = 18 :c = 4 – 19 + 10 = -5 :m = 30 + [0.6 x 15 – 3] – 6 = 30 :d = 18 :SB = 18 – 5 + 30 + 18 – 60 = 1 :S = B = 1, 甲子 *Stem-branch for October 1, 1949. :y = 5 x (1949–1920) + [29/4] = 5 x 5 + 7 = 32 :c = -5 :m = 30 + [0.6 x 11 -3] = 33 :d = 1 :SB = 32 – 5 + 33 + 1 – 60 = 1 :S = B = 1, 甲子

Ganzhi.io

An Open Source application and implementation of Gan & Zhi as well as Jeiqi {{Authority control Chinese calendars Chinese astrology Units of time Sexagenary cycle

Overview

Each term in the sexagenary cycle consists of two Chinese characters, the first being one of the ten Heavenly Stems of the Chinese ten-day week, Shang-era week and the second being one of the twelve Earthly Branches representing the years of Jupiter (planet), Jupiter's wikt:duodecennial, duodecennial orbital cycle. The first term ''jiǎzǐ'' () combines the first heavenly stem with the first earthly branch. The second term ''yǐchǒu'' () combines the second stem with the second branch. This pattern continues until both cycles conclude simultaneously with ''guǐhài'' (), after which it begins again at ''jiǎzǐ''. This termination at ten and twelve's least common multiple leaves half of the combinations—such as ''jiǎchǒu'' ()—unused; this is traditionally explained by reference to pairing the stems and branches according to their yin and yang properties.

This combination of two sub-cycles to generate a larger cycle and its use to record time have parallels in other calendrical systems, notably the Akan calendar.

Each term in the sexagenary cycle consists of two Chinese characters, the first being one of the ten Heavenly Stems of the Chinese ten-day week, Shang-era week and the second being one of the twelve Earthly Branches representing the years of Jupiter (planet), Jupiter's wikt:duodecennial, duodecennial orbital cycle. The first term ''jiǎzǐ'' () combines the first heavenly stem with the first earthly branch. The second term ''yǐchǒu'' () combines the second stem with the second branch. This pattern continues until both cycles conclude simultaneously with ''guǐhài'' (), after which it begins again at ''jiǎzǐ''. This termination at ten and twelve's least common multiple leaves half of the combinations—such as ''jiǎchǒu'' ()—unused; this is traditionally explained by reference to pairing the stems and branches according to their yin and yang properties.

This combination of two sub-cycles to generate a larger cycle and its use to record time have parallels in other calendrical systems, notably the Akan calendar.

History

The sexagenary cycle is attested as a method of recording days from the earliest written records in China, oracle bone inscriptions, records of divination on oracle bones, beginning ca. 1100 BC. Almost every oracle bone inscription includes a date in this format. This use of the cycle for days is attested throughout the Zhou dynasty and remained common into the Han dynasty, Han period for all documentary purposes that required dates specified to the day.

Almost all the dates in the ''Spring and Autumn Annals'', a chronological list of events from 722 to 481 BC, use this system in combination with regnal years and months (lunations) to record dates. Eclipses recorded in the Annals demonstrate that continuity in the sexagenary day-count was unbroken from that period onwards. It is likely that this unbroken continuity went back still further to the first appearance of the sexagenary cycle during the Shang period.

The use of the sexagenary cycle for recording years is much more recent. The earliest discovered documents showing this usage are among the silk manuscripts recovered from Mawangdui, Mawangdui tomb 3, sealed in 168 BC. In one of these documents, a sexagenary grid diagram is annotated in three places to mark notable events. For example, the first year of the reign of Qin Shi Huang (), 246 BC, is noted on the diagram next to the position of the 60-cycle term ''yǐ-mǎo'' (, 52 of 60), corresponding to that year. Use of the cycle to record years became widespread for administrative time-keeping during the Western Han dynasty (202 BC – 8 AD). The count of years has continued uninterrupted ever since: the year 1984 began the present cycle (a —''jiǎ-zǐ'' year), and 2044 will begin another. Note that in China the new year, when the sexagenary count increments, is not January 1, but rather the Chinese new year, lunar new year of the traditional Chinese calendar. For example, the ji-chou year (coinciding roughly with 2009) began on January 26, 2009. (However, for astrology, the year begins with the first solar term "Lìchūn" (), which occurs near February 4.)

In Japan, according to ''Nihon shoki'', the calendar was transmitted to Japan in 553. But it was not until the Empress Suiko, Suiko era that the calendar was used for politics. The year 604, when the Japanese officially adopted the Chinese calendar, was the first year of the cycle.

The Korean ( hwangap) and Japanese tradition ( ''kanreki'') of celebrating the 60th birthday (literally 'return of calendar') reflects the influence of the sexagenary cycle as a count of years.

The Tibetan calendar also counts years using a 60-year cycle based on 12 animals and 5 elements, but while the first year of the Chinese cycle is always the year of the Wood Rat (zodiac), Rat, the first year of the Tibetan cycle is the year of the Fire Rabbit (zodiac), Rabbit (—''dīng-mǎo'', year 4 on the Chinese cycle).

The sexagenary cycle is attested as a method of recording days from the earliest written records in China, oracle bone inscriptions, records of divination on oracle bones, beginning ca. 1100 BC. Almost every oracle bone inscription includes a date in this format. This use of the cycle for days is attested throughout the Zhou dynasty and remained common into the Han dynasty, Han period for all documentary purposes that required dates specified to the day.

Almost all the dates in the ''Spring and Autumn Annals'', a chronological list of events from 722 to 481 BC, use this system in combination with regnal years and months (lunations) to record dates. Eclipses recorded in the Annals demonstrate that continuity in the sexagenary day-count was unbroken from that period onwards. It is likely that this unbroken continuity went back still further to the first appearance of the sexagenary cycle during the Shang period.

The use of the sexagenary cycle for recording years is much more recent. The earliest discovered documents showing this usage are among the silk manuscripts recovered from Mawangdui, Mawangdui tomb 3, sealed in 168 BC. In one of these documents, a sexagenary grid diagram is annotated in three places to mark notable events. For example, the first year of the reign of Qin Shi Huang (), 246 BC, is noted on the diagram next to the position of the 60-cycle term ''yǐ-mǎo'' (, 52 of 60), corresponding to that year. Use of the cycle to record years became widespread for administrative time-keeping during the Western Han dynasty (202 BC – 8 AD). The count of years has continued uninterrupted ever since: the year 1984 began the present cycle (a —''jiǎ-zǐ'' year), and 2044 will begin another. Note that in China the new year, when the sexagenary count increments, is not January 1, but rather the Chinese new year, lunar new year of the traditional Chinese calendar. For example, the ji-chou year (coinciding roughly with 2009) began on January 26, 2009. (However, for astrology, the year begins with the first solar term "Lìchūn" (), which occurs near February 4.)

In Japan, according to ''Nihon shoki'', the calendar was transmitted to Japan in 553. But it was not until the Empress Suiko, Suiko era that the calendar was used for politics. The year 604, when the Japanese officially adopted the Chinese calendar, was the first year of the cycle.

The Korean ( hwangap) and Japanese tradition ( ''kanreki'') of celebrating the 60th birthday (literally 'return of calendar') reflects the influence of the sexagenary cycle as a count of years.

The Tibetan calendar also counts years using a 60-year cycle based on 12 animals and 5 elements, but while the first year of the Chinese cycle is always the year of the Wood Rat (zodiac), Rat, the first year of the Tibetan cycle is the year of the Fire Rabbit (zodiac), Rabbit (—''dīng-mǎo'', year 4 on the Chinese cycle).

Ten Heavenly Stems

Twelve Earthly Branches

Sexagenary years

Conversion between cyclic years and Western years

Examples

Step-by-step example to determine the sign for 1967: #1967 – 3 = 1964 ("subtracting 3 from the Gregorian year") #1964 ÷ 60 = 32 ("divide by 60 and discard any fraction") #1964 – (60 × 32) = 44 ("taking the remainder") #Show one of the Sexagenary Cycle tables (the following section), look for 44 in the first column (No) and obtain Fire Goat (zodiac), Goat (丁未; ''dīng-wèi''). Step-by-step example to determine the cyclic year of first year of the reign of Qin Shi Huang (246 BC): #246 + 2 = 248 ("adding 2 to the Gregorian year number (in BC)") #248 ÷ 60 = 4 ("divide by 60 and discard any fraction") #248 – (60 × 4) = 8 ("taking the remainder") #60 – 8 = 52 ("subtract the remainder from 60") #Show one of the Sexagenary Cycle table (the following section), look for 52 in the first column (No) and obtain Wood Rabbit (zodiac), Rabbit (乙卯; ''yǐ-mǎo'').A shorter equivalent method

Start from the AD year (1967), take directly the remainder mod 60, and look into column AD of the table "Sexagenary years" (just above). *1967 = 60 × 32 + 47. Remainder is therefore 47 and the AD column says 'Fire Goat (zodiac), Goat' as it should be. For a BC year: discard the minus sign, take the remainder of the year mod 60 and look into column BC. Applied to year -246, this gives: *246 = 60 × 4 + 6. Remainder is therefore 6 and the BC column of table "Sexagenary years" (just above) gives 'Wood Rabbit (zodiac), Rabbit'. When doing these conversions, year 246 BC cannot be treated as −246 AD due to the lack of a year 0 in the Gregorian AD/BC system. ---- The following tables show recent years (in the Gregorian calendar) and their corresponding years in the cycles:1804–1923

1924–2043

Sexagenary months

The branches are used marginally to indicate months. Despite there being twelve branches and twelve months in a year, the earliest use of branches to indicate a twelve-fold division of a year was in the 2nd century BC. They were coordinated with the orientations of the Great Dipper, (: ''jiànzǐyuè'', : ''jiànchǒuyuè'', etc.). There are two systems of placing these months, the lunar one and the solar one. One system follows the ordinary Chinese calendar, Chinese lunar calendar and connects the names of the months directly to the central solar term (; ''zhōngqì''). The ''jiànzǐyuè'' (()) is the month containing the winter solstice (i.e. the Dongzhi (solar term), Dōngzhì) ''zhōngqì''. The ''jiànchǒuyuè'' (()) is the month of the following ''zhōngqì'', which is Dahan (solar term), Dàhán (), while the ''jiànyínyuè'' (()) is that of the Yushui (solar term), Yǔshuǐ () ''zhōngqì'', etc. Intercalary months have the same branch as the preceding month. In the other system (; ''jiéyuè'') the "month" lasts for the period of two solar terms (two ''qìcì''). The ''zǐyuè'' () is the period starting with Daxue (solar term), Dàxuě (), i.e. the solar term ''before'' the winter solstice. The ''chǒuyuè'' () starts with Xiaohan, Xiǎohán (), the term before Dàhán (), while the ''yínyuè'' () starts with Lichun, Lìchūn (), the term before Yǔshuǐ (), etc. Thus in the solar system a month starts anywhere from about 15 days before to 15 days after its lunar counterpart. The branch names are not usual month names; the main use of the branches for months is astrological. However, the names are sometimes used to indicate historically which (lunar) month was the first month of the year in ancient times. For example, since the Han dynasty, the first month has been ''jiànyínyuè'', but earlier the first month was ''jiànzǐyuè'' (during the Zhou dynasty) or ''jiànchǒuyuè'' (traditionally during the Shang dynasty) as well. For astrological purposes stems are also necessary, and the months are named using the sexagenary cycle following a five-year cycle starting in a ''jiǎ'' (; 1st) or ''jǐ'' (; 6th) year. The first month of the ''jiǎ'' or ''jǐ'' year is a ''bǐng-yín'' (; 3rd) month, the next one is a ''dīng-mǎo'' (; 4th) month, etc., and the last month of the year is a ''dīng-chǒu'' (, 14th) month. The next year will start with a ''wù-yín'' (; 15th) month, etc. following the cycle. The 5th year will end with a ''yǐ-chǒu'' (; 2nd) month. The following month, the start of a ''jǐ'' or ''jiǎ'' year, will hence again be a ''bǐng-yín'' (3rd) month again. The beginning and end of the (solar) months in the table below are the approximate dates of current solar terms; they vary slightly from year to year depending on the leap days of the Gregorian calendar.Sexagenary days

*N for the year: (5y + [y/4]) mod 10, y = 0–39 (stem); (5y + [y/4]) mod 12, y = 0–15 (branch) *N for the Gregorian century: (4c + [c/4] + 2) mod 10 (stem); (8c + [c/4] + 2) mod 12 (branch), c ≥ 15 *N for the Julian century: 5c mod 10, c = 0–1 (stem); 9c mod 12, c = 0–3 (branch) The table above allows one to find the stem & branch for any given date. For both the stem and the branch, find the N for the row for the century, year, month, and day, then add them together. If the sum for the stems' N is above 10, subtract 10 until the result is between 1 and 10. If the sum for the branches' N is above 12, subtract 12 until the result is between 1 and 12. For any date before October 15, 1582, use the Julian calendar, Julian century column to find the row for that century's N. For dates after October 15, 1582, use the Gregorian calendar, Gregorian century column to find the century's N. When looking at dates in January and February of leap years, use the bold & italic ''Feb'' and ''Jan''.Examples

* Step-by-step example to determine the stem-branch for October 1, 1949. **Stem ***(day stem N + month stem N + year stem N + century stem N) = number of stem. If over 10, subtract 10 until within 1 – 10. ****Day 1: N = 1, ****Month of October: N = 1, ****Year 49: N = 7, *****49 isn't on the table, so we'll have to Modulo operation, mod 49 by 40. This gives us year 9, which we can follow to find the N for that row. ****Century 19: N = 2. ***(1 + 1 + 7 + 2) = 11. This is more than 10, so we'll subtract 10 to bring it between 1 and 10. ****11 – 10 = 1, ****Stem = 1, . **Branch ***(day branch N + month branch N + year branch N + century branch N)= number of branch. If over 12, subtract 12 until within 1 – 12. ****Day 1: N = 1, ****Month of October: N = 5, ****Year 49: N = 5, *****Again, 49 is not in the table for year. Modding 49 by 16 gives us 1, which we can look up to find the N of that row. ****Century 19: N = 2. ***(1 + 5 + 5 + 2) = 13. Since 13 is more than 12, we'll subtract 12 to bring it between 1 and 12. ****13 – 12 = 1, ****Branch = 1, . **Stem-branch = 1, 1 (, 1 in sexagenary cycle = 32 – 5 + 33 + 1 – 60). *Stem-branch for December 31, 1592 **Stem = (day stem N + month stem N + year stem N + century stem N) ***Day 31: N = 1; month of December: N = 2; year 92 (92 mod 40 = 12): N = 3; century 15: N = 5. ***(1 + 2 + 3 + 5) = 11; 11 – 10 = 1. ***Stem = 1, . **Branch = (day branch N + month branch N + year branch N + century branch N) ***Day 31: N = 7; month of December: N = 6; year 92 (92 mod 16 = 12): N = 3; century 15: N = 5. ***(7 + 6 + 3 + 5) = 21; 21 – 12 = 9. ***Branch = 9, **Stem-branch = 1, 9 (, 21 in cycle = – 42 – 2 + 34 + 31 = 21) *Stem-branch for August 4, 1338 **Stem = 8, ***Day 4: N = 4; month of August: N = 0; year 38: N = 9; century 13 (13 mod 2 = 1): N = 5. ***(4 + 0 + 9 + 5) = 18; 18 – 10 = 8. **Branch = 12, ***Day 4: N = 4; month of August: N = 4; year 38 (38 mod 16 = 6): N = 7; century 13 (13 mod 4 = 1): N = 9. ***(4 + 4 + 7 + 9) = 24; 24 – 12 = 12 **Stem-branch = 8, 12 (, 48 in cycle = 4 + 8 + 32 + 4) *Stem-branch for May 25, 105 BC (−104). **Stem = 7, ***Day 25: N = 5; month of May: N = 8; year −4 (−4 mod 40 = 36): N = 9; century −1 (−1 mod 2 = 1): N = 5. ***(5 + 8 + 9 + 5) = 27; 27 – 10 = 17; 17 – 10 = 7. **Branch = 3, ***Day 25: N = 1; month of May: N = 8; year −4 (−4 mod 16 = 12): N = 3; century −1 (−1 mod 4 = 3): N = 3. ***(1 + 8 + 3 + 3) = 15; 15 – 12 = 3. **Stem-branch = 7, 3 (, 27 in cycle = – 6 + 8 + 0 + 25) **Alternately, instead of doing both century and year, one can exclude the century and simply use −104 as the year for both the stem and the branch to get the same result. Algorithm for mental calculation : : : : for Gregorian calendar and for Julian calendar. :for Jan or Feb in a common year and in a leap year. *Stem-branch for February 22, 720 BC (−719). :y = 5 x (720–719) + [1/4] = 5 :c = 8 :m = 30 + [0.6 x 15 – 3] – 5 = 31 :d = 22 :SB = 5 + 8 + 31 + 22 – 60 = 6 :S = B = 6, 己巳 *Stem-branch for November 1, 211 BC (−210). :y = 5 x (240–210) + [30/4] = 5 x 6 + 7 = 37 :c = 8 :m = 0 + [0.6 x 12 – 3] = 4 :d = 1 :SB = 37 + 8 + 4 + 1 = 50 :S = 0, B = 2, 癸丑 *Stem-branch for February 18, 1912. :y = 5 x (1912–1920) + [-8/4] + 60 = 18 :c = 4 – 19 + 10 = -5 :m = 30 + [0.6 x 15 – 3] – 6 = 30 :d = 18 :SB = 18 – 5 + 30 + 18 – 60 = 1 :S = B = 1, 甲子 *Stem-branch for October 1, 1949. :y = 5 x (1949–1920) + [29/4] = 5 x 5 + 7 = 32 :c = -5 :m = 30 + [0.6 x 11 -3] = 33 :d = 1 :SB = 32 – 5 + 33 + 1 – 60 = 1 :S = B = 1, 甲子

Sexagenary hours

See also

* Doumu (斗母元君) * Tai Sui (太歲) * Chinese calendar * Chinese era name * Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–98) – Korean name of the event, "Imjin War", named after the "Yang Water (im) Dragon (zodiac), Dragon (jin)" year 1592. * Koshien Stadium (Japan), named after the "Yang Wood (kō) Rat (shi)" year 1924. One of the last examples of general usage of the cycle in Japan. * Lunisolar calendar * Xinhai Revolution (China), named after the "Yin Metal (xin) Pig (zodiac), Pig (hai)" year 1911References

Citations

Sources

* * *External links

*Ganzhi.io

An Open Source application and implementation of Gan & Zhi as well as Jeiqi {{Authority control Chinese calendars Chinese astrology Units of time Sexagenary cycle