X-Ray Diffraction on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

X-ray diffraction is a generic term for phenomena associated with changes in the direction of X-ray beams due to interactions with the electrons around atoms. It occurs due to

X-ray diffraction is a generic term for phenomena associated with changes in the direction of X-ray beams due to interactions with the electrons around atoms. It occurs due to

Crystals are regular arrays of atoms, and X-rays are electromagnetic waves. Atoms scatter X-ray waves, primarily through the atoms' electrons. Just as an ocean wave striking a lighthouse produces secondary circular waves emanating from the lighthouse, so an X-ray striking an electron produces secondary spherical waves emanating from the electron. This phenomenon is known as

Crystals are regular arrays of atoms, and X-rays are electromagnetic waves. Atoms scatter X-ray waves, primarily through the atoms' electrons. Just as an ocean wave striking a lighthouse produces secondary circular waves emanating from the lighthouse, so an X-ray striking an electron produces secondary spherical waves emanating from the electron. This phenomenon is known as

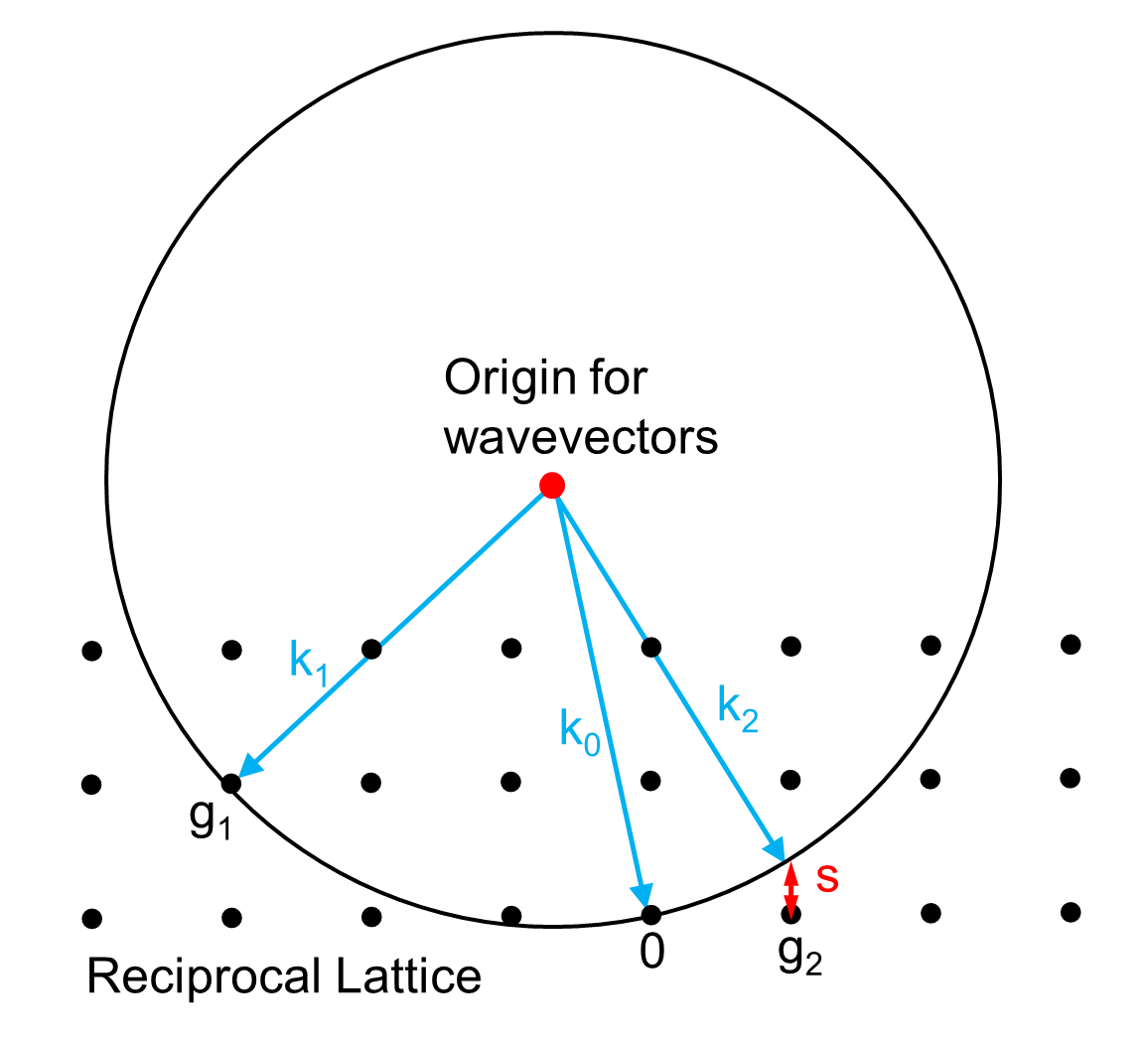

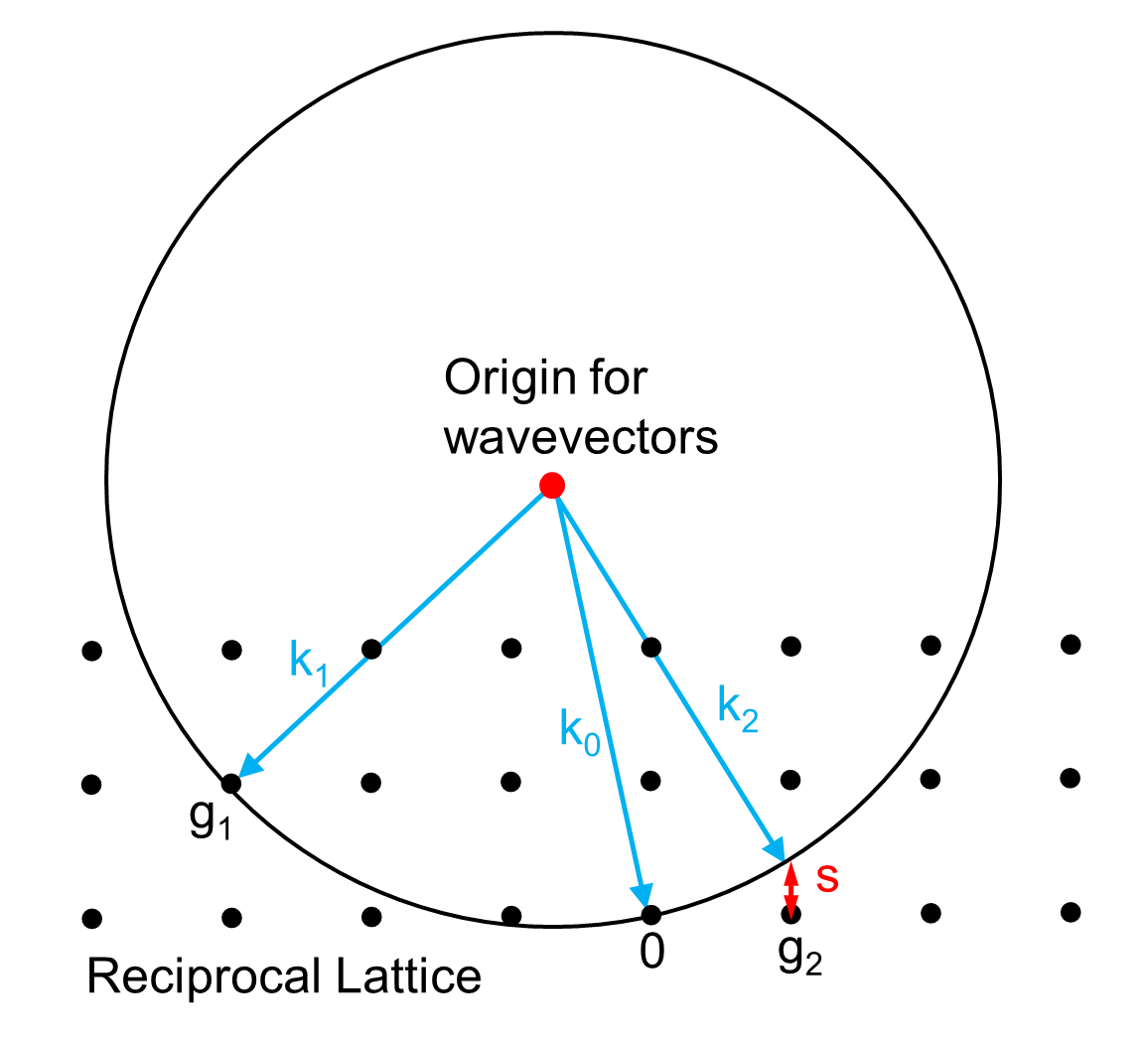

Each X-ray diffraction pattern represents a spherical slice of reciprocal space, as may be seen by the Ewald sphere construction. For a given incident wavevector k0 the only wavevectors with the same energy lie on the surface of a sphere. In the diagram, the wavevector k1 lies on the Ewald sphere and also is at a reciprocal lattice vector g1 so satisfies Bragg's law. In contrast the wavevector k2 differs from the reciprocal lattice point and g2 by the vector s which is called the excitation error. For large single crystals primarily used in crystallography only the Bragg's law case matters; for electron diffraction and some other types of x-ray diffraction non-zero values of the excitation error also matter.

Each X-ray diffraction pattern represents a spherical slice of reciprocal space, as may be seen by the Ewald sphere construction. For a given incident wavevector k0 the only wavevectors with the same energy lie on the surface of a sphere. In the diagram, the wavevector k1 lies on the Ewald sphere and also is at a reciprocal lattice vector g1 so satisfies Bragg's law. In contrast the wavevector k2 differs from the reciprocal lattice point and g2 by the vector s which is called the excitation error. For large single crystals primarily used in crystallography only the Bragg's law case matters; for electron diffraction and some other types of x-ray diffraction non-zero values of the excitation error also matter.

X-ray diffraction is a generic term for phenomena associated with changes in the direction of X-ray beams due to interactions with the electrons around atoms. It occurs due to

X-ray diffraction is a generic term for phenomena associated with changes in the direction of X-ray beams due to interactions with the electrons around atoms. It occurs due to elastic scattering

Elastic scattering is a form of particle scattering in scattering theory, nuclear physics and particle physics. In this process, the internal states of the Elementary particle, particles involved stay the same. In the non-relativistic case, where ...

, when there is no change in the energy of the waves. The resulting map of the directions of the X-rays far from the sample is called a diffraction pattern. It is different from X-ray crystallography

X-ray crystallography is the experimental science of determining the atomic and molecular structure of a crystal, in which the crystalline structure causes a beam of incident X-rays to Diffraction, diffract in specific directions. By measuring th ...

which exploits X-ray diffraction to determine the arrangement of atoms in materials, and also has other components such as ways to map from experimental diffraction measurements to the positions of atoms.

This article provides an overview of X-ray diffraction, starting with the early history

History is the systematic study of the past, focusing primarily on the Human history, human past. As an academic discipline, it analyses and interprets evidence to construct narratives about what happened and explain why it happened. Some t ...

of x-rays and the discovery that they have the right spacings to be diffracted by crystals. In many cases these diffraction patterns can be Interpreted using a single scattering or kinematical theory with conservation of energy (wave vector

In physics, a wave vector (or wavevector) is a vector used in describing a wave, with a typical unit being cycle per metre. It has a magnitude and direction. Its magnitude is the wavenumber of the wave (inversely proportional to the wavelength) ...

). Many different types of X-ray sources exist, ranging from ones used in laboratories to higher brightness synchrotron light sources. Similar diffraction patterns can be produced by related scattering techniques such as electron diffraction or neutron diffraction

Neutron diffraction or elastic neutron scattering is the application of neutron scattering to the determination of the atomic and/or magnetic structure of a material. A sample to be examined is placed in a beam of Neutron temperature, thermal or ...

. If single crystals of sufficient size cannot be obtained, various other X-ray methods can be applied to obtain less detailed information; such methods include fiber diffraction, powder diffraction and (if the sample is not crystallized) small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS).

History

WhenWilhelm Röntgen

Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen (; 27 March 1845 – 10 February 1923), sometimes Transliteration, transliterated as Roentgen ( ), was a German physicist who produced and detected electromagnetic radiation in a wavelength range known as X-rays. As ...

discovered X-rays in 1895 physicists were uncertain of the nature of X-rays, but suspected that they were waves of electromagnetic radiation

In physics, electromagnetic radiation (EMR) is a self-propagating wave of the electromagnetic field that carries momentum and radiant energy through space. It encompasses a broad spectrum, classified by frequency or its inverse, wavelength ...

. The Maxwell

Maxwell may refer to:

People

* Maxwell (surname), including a list of people and fictional characters with the name

** James Clerk Maxwell, mathematician and physicist

* Justice Maxwell (disambiguation)

* Maxwell baronets, in the Baronetage of N ...

theory of electromagnetic radiation

In physics, electromagnetic radiation (EMR) is a self-propagating wave of the electromagnetic field that carries momentum and radiant energy through space. It encompasses a broad spectrum, classified by frequency or its inverse, wavelength ...

was well accepted, and experiments by Charles Glover Barkla

Charles Glover Barkla (7 June 1877 – 23 October 1944) was an English physicist who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1917 for his discovery of characteristic X-rays.

Life

Barkla was born in Widnes, England, to John Martin Barkla, a sec ...

showed that X-rays exhibited phenomena associated with electromagnetic waves, including transverse polarization and spectral line

A spectral line is a weaker or stronger region in an otherwise uniform and continuous spectrum. It may result from emission (electromagnetic radiation), emission or absorption (electromagnetic radiation), absorption of light in a narrow frequency ...

s akin to those observed in the visible wavelengths. Barkla created the x-ray notation for sharp spectral lines, noting in 1909 two separate energies, at first, naming them "A" and "B" and, supposing that there may be lines prior to "A", he started an alphabet numbering beginning with "K."Michael Eckert, Disputed discovery: the beginnings of X-ray diffraction in crystals in 1912 and its repercussions, January 2011, Acta crystallographica. Section A, Foundations of crystallography 68(1):30–39 This Laue centennial article has also been published in Zeitschrift für Kristallographie ckert (2012). Z. Kristallogr. 227, 27–35 Single-slit experiments in the laboratory of Arnold Sommerfeld suggested that X-rays had a wavelength

In physics and mathematics, wavelength or spatial period of a wave or periodic function is the distance over which the wave's shape repeats.

In other words, it is the distance between consecutive corresponding points of the same ''phase (waves ...

of about 1 angstrom

The angstrom (; ) is a unit of length equal to m; that is, one ten-billionth of a metre, a hundred-millionth of a centimetre, 0.1 nanometre, or 100 picometres. The unit is named after the Swedish physicist Anders Jonas Ångström (1814–18 ...

. X-rays are not only waves but also have particle properties causing Sommerfeld to coin the name Bremsstrahlung for the continuous spectra when they were formed when electrons bombarded a material. Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein (14 March 187918 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist who is best known for developing the theory of relativity. Einstein also made important contributions to quantum mechanics. His mass–energy equivalence f ...

introduced the photon concept in 1905, but it was not broadly accepted until 1922, when Arthur Compton

Arthur Holly Compton (September 10, 1892 – March 15, 1962) was an American particle physicist who won the 1927 Nobel Prize in Physics for his discovery of the Compton effect, which demonstrated the particle nature of electromagnetic radiati ...

confirmed it by the scattering of X-rays from electrons. The particle-like properties of X-rays, such as their ionization of gases, had prompted William Henry Bragg to argue in 1907 that X-rays were ''not'' electromagnetic radiation. Bragg's view proved unpopular and the observation of X-ray diffraction by Max von Laue in 1912 confirmed that X-rays are a form of electromagnetic radiation.

The idea that crystals could be used as a diffraction grating

In optics, a diffraction grating is an optical grating with a periodic structure that diffraction, diffracts light, or another type of electromagnetic radiation, into several beams traveling in different directions (i.e., different diffractio ...

for X-ray

An X-ray (also known in many languages as Röntgen radiation) is a form of high-energy electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength shorter than those of ultraviolet rays and longer than those of gamma rays. Roughly, X-rays have a wavelength ran ...

s arose in 1912 in a conversation between Paul Peter Ewald and Max von Laue in the English Garden in Munich. Ewald had proposed a resonator model of crystals for his thesis, but this model could not be validated using visible light

Light, visible light, or visible radiation is electromagnetic radiation that can be perceived by the human eye. Visible light spans the visible spectrum and is usually defined as having wavelengths in the range of 400–700 nanometres (nm ...

, since the wavelength was much larger than the spacing between the resonators. Von Laue realized that electromagnetic radiation of a shorter wavelength was needed, and suggested that X-rays might have a wavelength comparable to the spacing in crystals. Von Laue worked with two technicians, Walter Friedrich and his assistant Paul Knipping, to shine a beam of X-rays through a copper sulfate crystal and record its diffraction pattern on a photographic plate. After being developed, the plate showed rings of fuzzy spots of roughly elliptical shape. Despite the crude and unclear image, the image confirmed the diffraction concept. The results were presented to the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities

The Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities () is an independent public institution, located in Munich. It appoints scholars whose research has contributed considerably to the increase of knowledge within their subject. The general goal of th ...

in June 1912 as "Interferenz-Erscheinungen bei Röntgenstrahlen" (Interference phenomena in X-rays).

After seeing the initial results, Laue was walking home and suddenly conceived of the physical laws describing the effect. Laue developed a law that connects the scattering angles and the size and orientation of the unit-cell spacings in the crystal, for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics

The Nobel Prize in Physics () is an annual award given by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences for those who have made the most outstanding contributions to mankind in the field of physics. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the ...

in 1914.

After Von Laue's pioneering research the field developed rapidly, most notably by physicists William Lawrence Bragg

Sir William Lawrence Bragg (31 March 1890 – 1 July 1971) was an Australian-born British physicist who shared the 1915 Nobel Prize in Physics with his father William Henry Bragg "for their services in the analysis of crystal structure by ...

and his father William Henry Bragg. In 1912–1913, the younger Bragg developed Bragg's law, which connects the scattering with evenly spaced planes within a crystal. The Braggs, father and son, shared the 1915 Nobel Prize in Physics for their work in crystallography. The earliest structures were generally simple; as computational and experimental methods improved over the next decades, it became feasible to deduce reliable atomic positions for more complicated arrangements of atoms; see X-ray crystallography

X-ray crystallography is the experimental science of determining the atomic and molecular structure of a crystal, in which the crystalline structure causes a beam of incident X-rays to Diffraction, diffract in specific directions. By measuring th ...

for more details.

Introduction to x-ray diffraction theory

Basics

elastic scattering

Elastic scattering is a form of particle scattering in scattering theory, nuclear physics and particle physics. In this process, the internal states of the Elementary particle, particles involved stay the same. In the non-relativistic case, where ...

, and the electron (or lighthouse) is known as the ''scatterer''. A regular array of scatterers produces a regular array of spherical waves. Although these waves cancel one another out in most directions through destructive interference, they add constructively in a few specific directions.

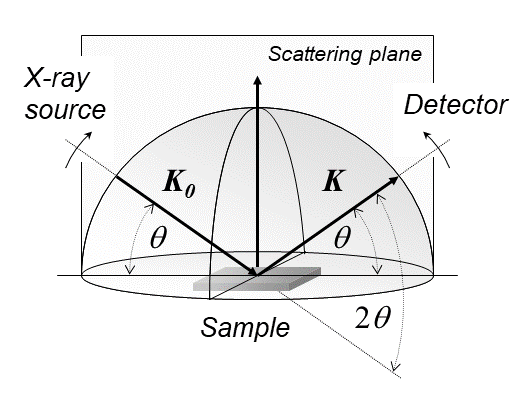

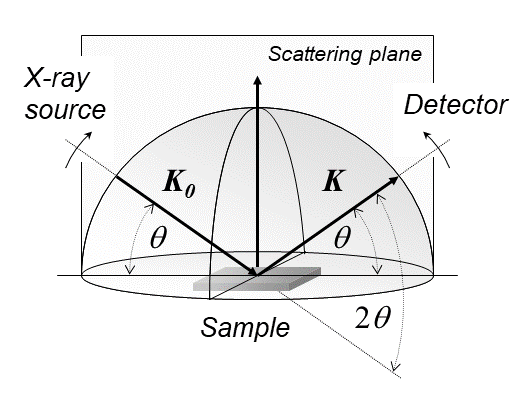

An intuitive understanding of X-ray diffraction can be obtained from the Bragg model of diffraction. In this model, a given reflection is associated with a set of evenly spaced sheets running through the crystal, usually passing through the centers of the atoms of the crystal lattice. The orientation of a particular set of sheets is identified by its three Miller indices (''h'', ''k'', ''l''), and their spacing by ''d''. William Lawrence Bragg proposed a model where the incoming X-rays are scattered specularly (mirror-like) from each plane; from that assumption, X-rays scattered from adjacent planes will combine constructively ( constructive interference) when the angle θ between the plane and the X-ray results in a path-length difference that is an integer multiple ''n'' of the X-ray wavelength λ.

:

A reflection is said to be ''indexed'' when its Miller indices (or, more correctly, its reciprocal lattice

Reciprocal lattice is a concept associated with solids with translational symmetry which plays a major role in many areas such as X-ray and electron diffraction as well as the energies of electrons in a solid. It emerges from the Fourier tran ...

vector components) have been identified from the known wavelength and the scattering angle 2θ. Such indexing gives the unit-cell parameters, the lengths and angles of the unit-cell, as well as its space group

In mathematics, physics and chemistry, a space group is the symmetry group of a repeating pattern in space, usually in three dimensions. The elements of a space group (its symmetry operations) are the rigid transformations of the pattern that ...

.

Ewald's sphere

Each X-ray diffraction pattern represents a spherical slice of reciprocal space, as may be seen by the Ewald sphere construction. For a given incident wavevector k0 the only wavevectors with the same energy lie on the surface of a sphere. In the diagram, the wavevector k1 lies on the Ewald sphere and also is at a reciprocal lattice vector g1 so satisfies Bragg's law. In contrast the wavevector k2 differs from the reciprocal lattice point and g2 by the vector s which is called the excitation error. For large single crystals primarily used in crystallography only the Bragg's law case matters; for electron diffraction and some other types of x-ray diffraction non-zero values of the excitation error also matter.

Each X-ray diffraction pattern represents a spherical slice of reciprocal space, as may be seen by the Ewald sphere construction. For a given incident wavevector k0 the only wavevectors with the same energy lie on the surface of a sphere. In the diagram, the wavevector k1 lies on the Ewald sphere and also is at a reciprocal lattice vector g1 so satisfies Bragg's law. In contrast the wavevector k2 differs from the reciprocal lattice point and g2 by the vector s which is called the excitation error. For large single crystals primarily used in crystallography only the Bragg's law case matters; for electron diffraction and some other types of x-ray diffraction non-zero values of the excitation error also matter.

Scattering amplitudes

X-ray scattering is determined by the density of electrons within the crystal. Since the energy of an X-ray is much greater than that of a valence electron, the scattering may be modeled as Thomson scattering, the elastic interaction of an electromagnetic ray with a charged particle. The intensity of Thomson scattering for one particle with mass ''m'' and elementary charge ''q'' is: : Hence the atomic nuclei, which are much heavier than an electron, contribute negligibly to the scattered X-rays. Consequently, the coherent scattering detected from an atom can be accurately approximated by analyzing the collective scattering from the electrons in the system. The incoming X-ray beam has a polarization and should be represented as a vector wave; however, for simplicity, it will be represented here as a scalar wave. We will ignore the time dependence of the wave and just concentrate on the wave's spatial dependence. Plane waves can be represented by awave vector

In physics, a wave vector (or wavevector) is a vector used in describing a wave, with a typical unit being cycle per metre. It has a magnitude and direction. Its magnitude is the wavenumber of the wave (inversely proportional to the wavelength) ...

kin, and so the incoming wave at time ''t'' = 0 is given by

:

At a position r within the sample, consider a density of scatterers ''f''(r); these scatterers produce a scattered spherical wave of amplitude proportional to the local amplitude of the incoming wave times the number of scatterers in a small volume ''dV'' about r

:

where ''S'' is the proportionality constant.

Consider the fraction of scattered waves that leave with an outgoing wave-vector of kout and strike a screen (detector) at rscreen. Since no energy is lost (elastic, not inelastic scattering), the wavelengths are the same as are the magnitudes of the wave-vectors , kin, = , kout, . From the time that the photon is scattered at r until it is absorbed at rscreen, the photon undergoes a change in phase

:

The net radiation arriving at rscreen is the sum of all the scattered waves throughout the crystal

:

which may be written as a Fourier transform

:

where g = kout – kin is a reciprocal lattice vector that satisfies Bragg's law and the Ewald construction mentioned above. The measured intensity of the reflection will be square of this amplitude

:

The above assumes that the crystalline regions as somewhat large, for instance microns

The micrometre (English in the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth English as used by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures; SI symbol: μm) or micrometer (American English), also commonly known by the non-SI term micron, is a uni ...

across, but also not so large that the X-rays are scattered more than once. If either of these is not the case then the diffracted intensities will be e more complicated.

X-ray sources

Rotating anode

Small scale diffraction experiments can be done with a local X-ray tube source, typically coupled with an image plate detector. These have the advantage of being relatively inexpensive and easy to maintain, and allow for quick screening and collection of samples. However, the wavelength of the X-rays produced is limited by the availability of differentanode

An anode usually is an electrode of a polarized electrical device through which conventional current enters the device. This contrasts with a cathode, which is usually an electrode of the device through which conventional current leaves the devic ...

materials. Furthermore, the intensity is limited by the power applied and cooling capacity available to avoid melting the anode. In such systems, electrons are boiled off of a cathode and accelerated through a strong electric potential of ~50 kV; having reached a high speed, the electrons collide with a metal plate, emitting '' bremsstrahlung'' and some strong spectral lines corresponding to the excitation of inner-shell electrons of the metal. The most common metal used is copper, which can be kept cool easily due to its high thermal conductivity

The thermal conductivity of a material is a measure of its ability to heat conduction, conduct heat. It is commonly denoted by k, \lambda, or \kappa and is measured in W·m−1·K−1.

Heat transfer occurs at a lower rate in materials of low ...

, and which produces strong Kα and Kβ lines. The Kβ line is sometimes suppressed with a thin (~10 μm) nickel foil. The simplest and cheapest variety of sealed X-ray tube has a stationary anode (the Crookes tube

A Crookes tube: light and dark. Electrons (cathode rays) travel in straight lines from the cathode ''(left)'', as shown by the shadow cast by the metal Maltese cross on the fluorescence of the righthand glass wall of the tube. The anode is the ...

) and runs with ~2 kW of electron beam power. The more expensive variety has a rotating-anode type source that runs with ~14 kW of e-beam power.

X-rays are generally filtered (by use of X-ray filter An X-ray filter (or compensating filter) is a device placed in front of an X-ray source in order to reduce the intensity of particular wavelengths from its spectrum and selectively alter the distribution of X-ray wavelengths within a given beam befo ...

s) to a single wavelength (made monochromatic) and collimated to a single direction before they are allowed to strike the crystal. The filtering not only simplifies the data analysis, but also removes radiation that degrades the crystal without contributing useful information. Collimation is done either with a collimator (basically, a long tube) or with an arrangement of gently curved mirrors. Mirror systems are preferred for small crystals (under 0.3 mm) or with large unit cells (over 150 Å).

Microfocus tube

A more recent development is the microfocus tube, which can deliver at least as high a beam flux (after collimation) as rotating-anode sources but only require a beam power of a few tens or hundreds of watts rather than requiring several kilowatts.Synchrotron radiation

Synchrotron radiation sources are some of the brightest light sources on earth and are some of the most powerful tools available for X-ray diffraction and crystallography. X-ray beams are generated in synchrotrons which accelerate electrically charged particles, often electrons, to nearly the speed of light and confine them in a (roughly) circular loop using magnetic fields. Synchrotrons are generally national facilities, each with several dedicated beamlines where data is collected without interruption. Synchrotrons were originally designed for use by high-energy physicists studyingsubatomic particle

In physics, a subatomic particle is a particle smaller than an atom. According to the Standard Model of particle physics, a subatomic particle can be either a composite particle, which is composed of other particles (for example, a baryon, lik ...

s and cosmic phenomena. The largest component of each synchrotron is its electron storage ring. This ring is not a perfect circle, but a many-sided polygon. At each corner of the polygon, or sector, precisely aligned magnets bend the electron stream. As the electrons' path is bent, they emit bursts of energy in the form of X-rays.

The intense ionizing radiation

Ionizing (ionising) radiation, including Radioactive decay, nuclear radiation, consists of subatomic particles or electromagnetic waves that have enough energy per individual photon or particle to ionization, ionize atoms or molecules by detaching ...

can cause radiation damage to samples, particularly macromolecular crystals. Cryo crystallography can protect the sample from radiation damage, by freezing the crystal at liquid nitrogen

Liquid nitrogen (LN2) is nitrogen in a liquid state at cryogenics, low temperature. Liquid nitrogen has a boiling point of about . It is produced industrially by fractional distillation of liquid air. It is a colorless, mobile liquid whose vis ...

temperatures (~100 K). Cryocrystallography methods are applied to home source rotating anode sources as well. However, synchrotron radiation frequently has the advantage of user-selectable wavelengths, allowing for anomalous scattering experiments which maximizes anomalous signal. This is critical in experiments such as single wavelength anomalous dispersion (SAD) and multi-wavelength anomalous dispersion (MAD).

Free-electron laser

Free-electron laser

A free-electron laser (FEL) is a fourth generation light source producing extremely brilliant and short pulses of radiation. An FEL functions much as a laser but employs relativistic electrons as a active laser medium, gain medium instead of using ...

s have been developed for use in X-ray diffraction and crystallography. These are the brightest X-ray sources currently available; with the X-rays coming in femtosecond bursts. The intensity of the source is such that atomic resolution diffraction patterns can be resolved for crystals otherwise too small for collection. However, the intense light source also destroys the sample, requiring multiple crystals to be shot. As each crystal is randomly oriented in the beam, hundreds of thousands of individual diffraction images must be collected in order to get a complete data set. This method, serial femtosecond crystallography, has been used in solving the structure of a number of protein crystal structures, sometimes noting differences with equivalent structures collected from synchrotron sources.

Related scattering techniques

Other X-ray techniques

Other forms of elastic X-ray scattering besides single-crystal diffraction include powder diffraction, small-angle X-ray scattering ( SAXS) and several types of X-ray fiber diffraction, which was used by Rosalind Franklin in determining the double-helix structure ofDNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

. In general, single-crystal X-ray diffraction offers more structural information than these other techniques; however, it requires a sufficiently large and regular crystal, which is not always available.

These scattering methods generally use ''monochromatic'' X-rays, which are restricted to a single wavelength with minor deviations. A broad spectrum of X-rays (that is, a blend of X-rays with different wavelengths) can also be used to carry out X-ray diffraction, a technique known as the Laue method. This is the method used in the original discovery of X-ray diffraction. Laue scattering provides much structural information with only a short exposure to the X-ray beam, and is therefore used in structural studies of very rapid events ( time resolved crystallography). However, it is not as well-suited as monochromatic scattering for determining the full atomic structure of a crystal and therefore works better with crystals with relatively simple atomic arrangements.

The Laue back reflection mode records X-rays scattered backwards from a broad spectrum source. This is useful if the sample is too thick for X-rays to transmit through it. The diffracting planes in the crystal are determined by knowing that the normal to the diffracting plane bisects the angle between the incident beam and the diffracted beam. A Greninger chart

In crystallography, a Greninger chartIt is named after Alden Buchanan Greninger (17 September 1907, Glendale, Oregon20 April 1998). is a chart that allows angular relations between zones and planes in a crystal to be directly read from an x-ray d ...

can be used to interpret the back reflection Laue photograph.

Electron diffraction

Because they interact via the Coulomb forces the scattering of electrons by matter is 1000 or more times stronger than for X-rays. Hence electron beams produce strong multiple or dynamical scattering even for relatively thin crystals (>10 nm). While there are similarities between the diffraction of X-rays and electrons, as can be found in the book by John M. Cowley, the approach is different as it is based upon the original approach of Hans Bethe and solvingSchrödinger equation

The Schrödinger equation is a partial differential equation that governs the wave function of a non-relativistic quantum-mechanical system. Its discovery was a significant landmark in the development of quantum mechanics. It is named after E ...

for relativistic electrons, rather than a kinematical or Bragg's law approach. Information about very small regions, down to single atoms is possible. The range of applications for electron diffraction, transmission electron microscopy

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) is a microscopy technique in which a beam of electrons is transmitted through a specimen to form an image. The specimen is most often an ultrathin section less than 100 nm thick or a suspension on a g ...

and transmission electron crystallography with high energy electrons is extensive; see the relevant links for more information and citations. In addition to transmission methods, low-energy electron diffraction

Low-energy electron diffraction (LEED) is a technique for the determination of the surface structure of single crystal, single-crystalline materials by bombardment with a collimated beam of low-energy electrons (30–200 eV) and observation o ...

is a technique where electrons are back-scattered off surfaces and has been extensively used to determine surface structures at the atomic scale, and reflection high-energy electron diffraction is another which is extensively used to monitor thin film growth.

Neutron diffraction

Neutron diffraction is used for structure determination, although it has been difficult to obtain intense, monochromatic beams of neutrons in sufficient quantities. Traditionally,nuclear reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a Nuclear fission, fission nuclear chain reaction. They are used for Nuclear power, commercial electricity, nuclear marine propulsion, marine propulsion, Weapons-grade plutonium, weapons ...

s have been used, although sources producing neutrons by spallation are becoming increasingly available. Being uncharged, neutrons scatter more from the atomic nuclei rather than from the electrons. Therefore, neutron scattering is useful for observing the positions of light atoms with few electrons, especially hydrogen

Hydrogen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol H and atomic number 1. It is the lightest and abundance of the chemical elements, most abundant chemical element in the universe, constituting about 75% of all baryon, normal matter ...

, which is essentially invisible in X-ray diffraction. Neutron scattering also has the property that the solvent can be made invisible by adjusting the ratio of normal water, H2O, and heavy water

Heavy water (deuterium oxide, , ) is a form of water (molecule), water in which hydrogen atoms are all deuterium ( or D, also known as ''heavy hydrogen'') rather than the common hydrogen-1 isotope (, also called ''protium'') that makes up most o ...

, D2O.

References

{{Reflist, 30em Laboratory techniques in condensed matter physics Crystallography Diffraction Materials science Synchrotron-related techniquesCrystallography

Crystallography is the branch of science devoted to the study of molecular and crystalline structure and properties. The word ''crystallography'' is derived from the Ancient Greek word (; "clear ice, rock-crystal"), and (; "to write"). In J ...