Names

The term ''world war'' was first coined in September 1914 by German biologist and philosopher Ernst Haeckel. He claimed that "there is no doubt that the course and character of the feared 'European War' ... will become the first world war in the full sense of the word," in ''Background

Political and military alliances

Arms race

German industrial strength significantly increased after 1871, driven by the creation of a unified Reich,

German industrial strength significantly increased after 1871, driven by the creation of a unified Reich, Conflicts in the Balkans

The years before 1914 were marked by a series of crises in the Balkans as other powers sought to benefit from Ottoman decline. While

The years before 1914 were marked by a series of crises in the Balkans as other powers sought to benefit from Ottoman decline. While Prelude

Sarajevo assassination

On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, heir presumptive to Emperor

On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, heir presumptive to Emperor Expansion of violence in Bosnia and Herzegovina

The Austro-Hungarian authorities encouraged the subsequent

The Austro-Hungarian authorities encouraged the subsequent July Crisis

The assassination initiated the At a meeting on 29 July, the British cabinet had narrowly decided its obligations to Belgium under the 1839 Treaty of London did not require it to oppose a German invasion with military force. However, this was largely driven by Prime Minister

At a meeting on 29 July, the British cabinet had narrowly decided its obligations to Belgium under the 1839 Treaty of London did not require it to oppose a German invasion with military force. However, this was largely driven by Prime Minister Progress of the war

Opening hostilities

Confusion among the Central Powers

The strategy of the Central Powers suffered from miscommunication. Germany had promised to support Austria-Hungary's invasion of Serbia, but interpretations of what this meant differed. Previously tested deployment plans had been replaced early in 1914, but those had never been tested in exercises. Austro-Hungarian leaders believed Germany would cover its northern flank against Russia. Germany, however, envisioned Austria-Hungary directing most of its troops against Russia, while Germany dealt with France. This confusion forced the Austro-Hungarian Army to divide its forces between the Russian and Serbian fronts.Serbian campaign

Beginning on 12 August, the Austrian and Serbs clashed at the battles of the Battle of Cer, Cer and Battle of Kolubara, Kolubara; over the next two weeks, Austrian attacks were repulsed with heavy losses, dashing their hopes of a swift victory and marking the first major Allied victories of the war. As a result, Austria had to keep sizeable forces on the Serbian front, weakening its efforts against Russia. Serbia's defeat of the 1914 invasion has been called one of the major upset victories of the twentieth century. In spring 1915, the campaign saw the first use of anti-aircraft warfare after an Austrian plane was shot down with Surface-to-air missile, ground-to-air fire, as well as the first medical evacuation by the Serbian army in autumn 1915.

Beginning on 12 August, the Austrian and Serbs clashed at the battles of the Battle of Cer, Cer and Battle of Kolubara, Kolubara; over the next two weeks, Austrian attacks were repulsed with heavy losses, dashing their hopes of a swift victory and marking the first major Allied victories of the war. As a result, Austria had to keep sizeable forces on the Serbian front, weakening its efforts against Russia. Serbia's defeat of the 1914 invasion has been called one of the major upset victories of the twentieth century. In spring 1915, the campaign saw the first use of anti-aircraft warfare after an Austrian plane was shot down with Surface-to-air missile, ground-to-air fire, as well as the first medical evacuation by the Serbian army in autumn 1915.

German Offensive in Belgium and France

Upon mobilisation in 1914, 80% of the German Army order of battle (1914), German Army was located on the Western Front, with the remainder acting as a screening force in the East; officially titled ''Aufmarsch II West,'' it is better known as the

Upon mobilisation in 1914, 80% of the German Army order of battle (1914), German Army was located on the Western Front, with the remainder acting as a screening force in the East; officially titled ''Aufmarsch II West,'' it is better known as the  The initial German advance in the West was very successful and by the end of August the Allied left, which included the British Expeditionary Force (World War I), British Expeditionary Force (BEF), was in Great Retreat, full retreat. At the same time, the French offensive in Alsace-Lorraine was a disastrous failure, with casualties exceeding 260,000, including 27,000 killed on 22 August during the Battle of the Frontiers. German planning provided broad strategic instructions, while allowing army commanders considerable freedom in carrying them out at the front; this worked well in 1866 and 1870 but in 1914, Alexander von Kluck, von Kluck used this freedom to disobey orders, opening a gap between the German armies as they closed on Paris. The French and British exploited this gap to halt the German advance east of Paris at the First Battle of the Marne from 5to 12 September and push the German forces back some .

In 1911, the Russian Stavka had agreed with the French to attack Germany within fifteen days of mobilisation, ten days before the Germans had anticipated, although it meant the two Russian armies that entered East Prussia on 17 August did so without many of their support elements. Although the 2nd Army (Russian Empire), Russian Second Army was effectively destroyed at the Battle of Tannenberg on 26–30 August, their advance caused the Germans to re-route their 8th Army (German Empire), 8th Field Army from France to East Prussia, a factor in Allied victory on the Marne.

By the end of 1914, German troops held strong defensive positions inside France, controlled the bulk of France's domestic coalfields and had inflicted 230,000 more casualties than it lost itself. However, communications problems and questionable command decisions cost Germany the chance of a decisive outcome, while it had failed to achieve the primary objective of avoiding a long, two-front war. As was apparent to a number of German leaders, this amounted to a strategic defeat; shortly after the Marne, Wilhelm, German Crown Prince, Crown Prince Wilhelm told an American reporter; "We have lost the war. It will go on for a long time but lost it is already."

The initial German advance in the West was very successful and by the end of August the Allied left, which included the British Expeditionary Force (World War I), British Expeditionary Force (BEF), was in Great Retreat, full retreat. At the same time, the French offensive in Alsace-Lorraine was a disastrous failure, with casualties exceeding 260,000, including 27,000 killed on 22 August during the Battle of the Frontiers. German planning provided broad strategic instructions, while allowing army commanders considerable freedom in carrying them out at the front; this worked well in 1866 and 1870 but in 1914, Alexander von Kluck, von Kluck used this freedom to disobey orders, opening a gap between the German armies as they closed on Paris. The French and British exploited this gap to halt the German advance east of Paris at the First Battle of the Marne from 5to 12 September and push the German forces back some .

In 1911, the Russian Stavka had agreed with the French to attack Germany within fifteen days of mobilisation, ten days before the Germans had anticipated, although it meant the two Russian armies that entered East Prussia on 17 August did so without many of their support elements. Although the 2nd Army (Russian Empire), Russian Second Army was effectively destroyed at the Battle of Tannenberg on 26–30 August, their advance caused the Germans to re-route their 8th Army (German Empire), 8th Field Army from France to East Prussia, a factor in Allied victory on the Marne.

By the end of 1914, German troops held strong defensive positions inside France, controlled the bulk of France's domestic coalfields and had inflicted 230,000 more casualties than it lost itself. However, communications problems and questionable command decisions cost Germany the chance of a decisive outcome, while it had failed to achieve the primary objective of avoiding a long, two-front war. As was apparent to a number of German leaders, this amounted to a strategic defeat; shortly after the Marne, Wilhelm, German Crown Prince, Crown Prince Wilhelm told an American reporter; "We have lost the war. It will go on for a long time but lost it is already."

Asia and the Pacific

African campaigns

Some of the first clashes of the war involved British, French, and German colonial forces in Africa. On 6–7 August, French and British troops invaded the German protectorate of Togoland and Kamerun. On 10 August, German forces in German South West Africa, South-West Africa attacked South Africa; sporadic and fierce fighting continued for the rest of the war. The German colonial forces in German East Africa, led by Colonel Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, fought a guerrilla warfare campaign during World WarI and only surrendered two weeks after the armistice took effect in Europe.Indian support for the Allies

Prior to the war, Germany had attempted to use Indian nationalism and pan-Islamism to its advantage, a policy continued post-1914 by Hindu–German Conspiracy, instigating uprisings in India, while the Niedermayer–Hentig Expedition urged Afghanistan to join the war on the side of Central Powers. However, contrary to British fears of a revolt in India, the outbreak of the war saw a reduction in nationalist activity. This was largely because leaders from the Indian National Congress and other groups believed support for the British war effort would hasten Indian Home Rule movement, Indian Home Rule, a promise allegedly made explicit in 1917 by Edwin Montagu, then Secretary of State for India.

In 1914, the British Indian Army was larger than the British Army itself, and between 1914 and 1918 an estimated 1.3 million Indian soldiers and labourers served in Europe, Africa, and the Middle East, while the British Raj, Government of India and their princely state, princely allies supplied large quantities of food, money, and ammunition. In all, 140,000 soldiers served on the Western Front and nearly 700,000 in the Middle East, with 47,746 killed and 65,126 wounded.

The suffering engendered by the war, as well as the failure of the British government to grant self-government to India after the end of hostilities, bred disillusionment and fuelled Indian independence movement, the campaign for full independence that would be led by Mahatma Gandhi and others.

Prior to the war, Germany had attempted to use Indian nationalism and pan-Islamism to its advantage, a policy continued post-1914 by Hindu–German Conspiracy, instigating uprisings in India, while the Niedermayer–Hentig Expedition urged Afghanistan to join the war on the side of Central Powers. However, contrary to British fears of a revolt in India, the outbreak of the war saw a reduction in nationalist activity. This was largely because leaders from the Indian National Congress and other groups believed support for the British war effort would hasten Indian Home Rule movement, Indian Home Rule, a promise allegedly made explicit in 1917 by Edwin Montagu, then Secretary of State for India.

In 1914, the British Indian Army was larger than the British Army itself, and between 1914 and 1918 an estimated 1.3 million Indian soldiers and labourers served in Europe, Africa, and the Middle East, while the British Raj, Government of India and their princely state, princely allies supplied large quantities of food, money, and ammunition. In all, 140,000 soldiers served on the Western Front and nearly 700,000 in the Middle East, with 47,746 killed and 65,126 wounded.

The suffering engendered by the war, as well as the failure of the British government to grant self-government to India after the end of hostilities, bred disillusionment and fuelled Indian independence movement, the campaign for full independence that would be led by Mahatma Gandhi and others.

Western Front 1914 to 1916

Trench warfare begins

Pre-war military tactics that emphasised open warfare and the individual rifleman proved obsolete when confronted with conditions prevailing in 1914. Technological advances allowed the creation of strong defensive systems largely impervious to massed infantry advances, such as barbed wire, machine guns and above all far more powerful artillery, which dominated the battlefield and made crossing open ground extremely difficult. Both sides struggled to develop tactics for breaching entrenched positions without suffering heavy casualties. In time, however, technology began to produce new offensive weapons, such as Chemical weapons in World War I, gas warfare and the Tanks in World War I, tank.

After the First Battle of the Marne in September 1914, Allied and German forces unsuccessfully tried to outflank each other, a series of manoeuvres later known as the "Race to the Sea". By the end of 1914, the opposing forces confronted each other along an uninterrupted line of entrenched positions from the English Channel, Channel to the Swiss border. Since the Germans were normally able to choose where to stand, they generally held the high ground, while their trenches tended to be better built; those constructed by the French and English were initially considered "temporary", only needed until an offensive would smash the German defences. Both sides tried to break the stalemate using scientific and technological advances. On 22 April 1915, at the Second Battle of Ypres, the Germans (violating the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907, Hague Convention) used chlorine gas for the first time on the Western Front. Several types of gas soon became widely used by both sides, and though it never proved a decisive, battle-winning weapon, it became one of the most-feared and best-remembered horrors of the war.

Pre-war military tactics that emphasised open warfare and the individual rifleman proved obsolete when confronted with conditions prevailing in 1914. Technological advances allowed the creation of strong defensive systems largely impervious to massed infantry advances, such as barbed wire, machine guns and above all far more powerful artillery, which dominated the battlefield and made crossing open ground extremely difficult. Both sides struggled to develop tactics for breaching entrenched positions without suffering heavy casualties. In time, however, technology began to produce new offensive weapons, such as Chemical weapons in World War I, gas warfare and the Tanks in World War I, tank.

After the First Battle of the Marne in September 1914, Allied and German forces unsuccessfully tried to outflank each other, a series of manoeuvres later known as the "Race to the Sea". By the end of 1914, the opposing forces confronted each other along an uninterrupted line of entrenched positions from the English Channel, Channel to the Swiss border. Since the Germans were normally able to choose where to stand, they generally held the high ground, while their trenches tended to be better built; those constructed by the French and English were initially considered "temporary", only needed until an offensive would smash the German defences. Both sides tried to break the stalemate using scientific and technological advances. On 22 April 1915, at the Second Battle of Ypres, the Germans (violating the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907, Hague Convention) used chlorine gas for the first time on the Western Front. Several types of gas soon became widely used by both sides, and though it never proved a decisive, battle-winning weapon, it became one of the most-feared and best-remembered horrors of the war.

Continuation of trench warfare

Neither side proved able to deliver a decisive blow for the next two years. Throughout 1915–17, the British Empire and France suffered more casualties than Germany, because of both the strategic and tactical stances chosen by the sides. Strategically, while the Germans mounted only one major offensive, the Allies made several attempts to break through the German lines. In February 1916 the Germans attacked French defensive positions at the Battle of Verdun, lasting until December 1916. The Germans made initial gains, before French counter-attacks returned matters to near their starting point. Casualties were greater for the French, but the Germans bled heavily as well, with anywhere from 700,000 to 975,000 casualties suffered between the two combatants. Verdun became a symbol of French determination and self-sacrifice.

The Battle of the Somme was an Anglo-French offensive of July to November 1916. The first day on the Somme, opening day on 1 July 1916 was the bloodiest single day in the history of the British Army, which suffered 57,470 casualties, including 19,240 dead. As a whole, the Somme offensive led to an estimated 420,000 British casualties, along with 200,000 French and 500,000 German. Gun fire was not the only factor taking lives; the diseases that emerged in the trenches were a major killer on both sides. The living conditions made it so that countless diseases and infections occurred, such as trench foot, shell shock, blindness/burns from mustard gas, louse, lice, trench fever, "cooties" (body louse, body lice) and the 'Spanish flu'.

In February 1916 the Germans attacked French defensive positions at the Battle of Verdun, lasting until December 1916. The Germans made initial gains, before French counter-attacks returned matters to near their starting point. Casualties were greater for the French, but the Germans bled heavily as well, with anywhere from 700,000 to 975,000 casualties suffered between the two combatants. Verdun became a symbol of French determination and self-sacrifice.

The Battle of the Somme was an Anglo-French offensive of July to November 1916. The first day on the Somme, opening day on 1 July 1916 was the bloodiest single day in the history of the British Army, which suffered 57,470 casualties, including 19,240 dead. As a whole, the Somme offensive led to an estimated 420,000 British casualties, along with 200,000 French and 500,000 German. Gun fire was not the only factor taking lives; the diseases that emerged in the trenches were a major killer on both sides. The living conditions made it so that countless diseases and infections occurred, such as trench foot, shell shock, blindness/burns from mustard gas, louse, lice, trench fever, "cooties" (body louse, body lice) and the 'Spanish flu'.

Naval war

At the start of the war, German cruisers were scattered across the globe, some of which were subsequently used to attack Allied maritime transport, merchant shipping. The British Royal Navy systematically hunted them down, though not without some embarrassment from its inability to protect Allied shipping. For example, the light cruiser , which was part of the German East Asia Squadron stationed at Qingdao, seized or sank 15 merchantmen, as well as a Russian cruiser and a French destroyer. Most of the squadron was returning to Germany when it sank two British warships armoured cruisers at the Battle of Coronel in November 1914, before being virtually destroyed at the Battle of the Falkland Islands in December. The SMS Dresden (1907), SMS Dresden escaped with a few auxiliaries, but after the Battle of Más a Tierra, these too had either been destroyed or interned.

Soon after the outbreak of hostilities, Britain began a naval blockade of Germany. The strategy proved effective, cutting off vital military and civilian supplies, although this blockade violated accepted international law codified by several international agreements of the past two centuries. Britain mined international waters to prevent any ships from entering entire sections of ocean, causing danger to even neutral ships. Since there was limited response to this tactic of the British, Germany expected a similar response to its unrestricted submarine warfare.

The Battle of Jutland (German: ''Skagerrakschlacht'', or "Battle of the Skagerrak") in May/June 1916 developed into the largest naval battle of the war. It was the only full-scale clash of battleships during the war, and one of the largest in history. The Kaiserliche Marine's High Seas Fleet, commanded by Vice Admiral Reinhard Scheer, fought the Royal Navy's Grand Fleet, led by Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, 1st Earl Jellicoe, John Jellicoe. The engagement was a stand off, as the Germans were outmanoeuvred by the larger British fleet, but managed to escape and inflicted more damage to the British fleet than they received. Strategically, however, the British asserted their control of the sea, and the bulk of the German surface fleet remained confined to port for the duration of the war.

At the start of the war, German cruisers were scattered across the globe, some of which were subsequently used to attack Allied maritime transport, merchant shipping. The British Royal Navy systematically hunted them down, though not without some embarrassment from its inability to protect Allied shipping. For example, the light cruiser , which was part of the German East Asia Squadron stationed at Qingdao, seized or sank 15 merchantmen, as well as a Russian cruiser and a French destroyer. Most of the squadron was returning to Germany when it sank two British warships armoured cruisers at the Battle of Coronel in November 1914, before being virtually destroyed at the Battle of the Falkland Islands in December. The SMS Dresden (1907), SMS Dresden escaped with a few auxiliaries, but after the Battle of Más a Tierra, these too had either been destroyed or interned.

Soon after the outbreak of hostilities, Britain began a naval blockade of Germany. The strategy proved effective, cutting off vital military and civilian supplies, although this blockade violated accepted international law codified by several international agreements of the past two centuries. Britain mined international waters to prevent any ships from entering entire sections of ocean, causing danger to even neutral ships. Since there was limited response to this tactic of the British, Germany expected a similar response to its unrestricted submarine warfare.

The Battle of Jutland (German: ''Skagerrakschlacht'', or "Battle of the Skagerrak") in May/June 1916 developed into the largest naval battle of the war. It was the only full-scale clash of battleships during the war, and one of the largest in history. The Kaiserliche Marine's High Seas Fleet, commanded by Vice Admiral Reinhard Scheer, fought the Royal Navy's Grand Fleet, led by Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, 1st Earl Jellicoe, John Jellicoe. The engagement was a stand off, as the Germans were outmanoeuvred by the larger British fleet, but managed to escape and inflicted more damage to the British fleet than they received. Strategically, however, the British asserted their control of the sea, and the bulk of the German surface fleet remained confined to port for the duration of the war.

German U-boats attempted to cut the supply lines between North America and Britain. The nature of submarine warfare meant that attacks often came without warning, giving the crews of the merchant ships little hope of survival. The United States launched a protest, and Germany changed its rules of engagement. After the sinking of the passenger ship RMS Lusitania, RMS ''Lusitania'' in 1915, Germany promised not to target passenger liners, while Britain armed its merchant ships, placing them beyond the protection of the "Prize (law), cruiser rules", which demanded warning and movement of crews to "a place of safety" (a standard that lifeboats did not meet). Finally, in early 1917, Germany adopted a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare, realising the Americans would eventually enter the war. Germany sought to strangle Allied sea lanes before the United States could transport a large army overseas, but after initial successes eventually failed to do so.

The U-boat threat lessened in 1917, when merchant ships began travelling in Convoys in World War I, convoys, escorted by destroyers. This tactic made it difficult for U-boats to find targets, which significantly lessened losses; after the hydrophone and depth charges were introduced, accompanying destroyers could attack a submerged submarine with some hope of success. Convoys slowed the flow of supplies since ships had to wait as convoys were assembled. The solution to the delays was an extensive program of building new freighters. Troopships were too fast for the submarines and did not travel the North Atlantic in convoys. The U-boats had sunk more than 5,000 Allied ships, at a cost of 199 submarines.

World War I also saw the first use of aircraft carriers in combat, with launching Sopwith Camels in a successful raid against the Zeppelin hangars at Tondern raid, Tondern in July 1918, as well as blimps for antisubmarine patrol.

German U-boats attempted to cut the supply lines between North America and Britain. The nature of submarine warfare meant that attacks often came without warning, giving the crews of the merchant ships little hope of survival. The United States launched a protest, and Germany changed its rules of engagement. After the sinking of the passenger ship RMS Lusitania, RMS ''Lusitania'' in 1915, Germany promised not to target passenger liners, while Britain armed its merchant ships, placing them beyond the protection of the "Prize (law), cruiser rules", which demanded warning and movement of crews to "a place of safety" (a standard that lifeboats did not meet). Finally, in early 1917, Germany adopted a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare, realising the Americans would eventually enter the war. Germany sought to strangle Allied sea lanes before the United States could transport a large army overseas, but after initial successes eventually failed to do so.

The U-boat threat lessened in 1917, when merchant ships began travelling in Convoys in World War I, convoys, escorted by destroyers. This tactic made it difficult for U-boats to find targets, which significantly lessened losses; after the hydrophone and depth charges were introduced, accompanying destroyers could attack a submerged submarine with some hope of success. Convoys slowed the flow of supplies since ships had to wait as convoys were assembled. The solution to the delays was an extensive program of building new freighters. Troopships were too fast for the submarines and did not travel the North Atlantic in convoys. The U-boats had sunk more than 5,000 Allied ships, at a cost of 199 submarines.

World War I also saw the first use of aircraft carriers in combat, with launching Sopwith Camels in a successful raid against the Zeppelin hangars at Tondern raid, Tondern in July 1918, as well as blimps for antisubmarine patrol.

Southern theatres

War in the Balkans

Ottoman Empire

The Ottomans threatened Russia's Caucasus, Caucasian territories and Britain's communications with India via the Suez Canal. As the conflict progressed, the Ottoman Empire took advantage of the European powers' preoccupation with the war and conducted large-scale ethnic cleansing of the indigenous Armenians, Armenian, Greeks, Greek, and Assyrian people, Assyrian Christian populations, known as the Armenian genocide, Greek genocide, and Sayfo, Assyrian genocide.

The British and French opened overseas fronts with the Gallipoli (1915) and Mesopotamian campaigns (1914). In Gallipoli, the Ottoman Empire successfully repelled the British, French, and Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZACs). In Mesopotamia, by contrast, after the defeat of the British defenders in the siege of Kut by the Ottomans (1915–16), British Imperial forces reorganised and captured Baghdad in March 1917. The British were aided in Mesopotamia by local Arab and Assyrian fighters, while the Ottomans employed local Kurds, Kurdish and Iraqi Turkmen, Turcoman tribes.

The Ottomans threatened Russia's Caucasus, Caucasian territories and Britain's communications with India via the Suez Canal. As the conflict progressed, the Ottoman Empire took advantage of the European powers' preoccupation with the war and conducted large-scale ethnic cleansing of the indigenous Armenians, Armenian, Greeks, Greek, and Assyrian people, Assyrian Christian populations, known as the Armenian genocide, Greek genocide, and Sayfo, Assyrian genocide.

The British and French opened overseas fronts with the Gallipoli (1915) and Mesopotamian campaigns (1914). In Gallipoli, the Ottoman Empire successfully repelled the British, French, and Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZACs). In Mesopotamia, by contrast, after the defeat of the British defenders in the siege of Kut by the Ottomans (1915–16), British Imperial forces reorganised and captured Baghdad in March 1917. The British were aided in Mesopotamia by local Arab and Assyrian fighters, while the Ottomans employed local Kurds, Kurdish and Iraqi Turkmen, Turcoman tribes.

Further to the west, the Suez Canal was defended from Ottoman attacks in 1915 and 1916; in August, a German and Ottoman force was defeated at the Battle of Romani by the ANZAC Mounted Division and the 52nd (Lowland) Infantry Division. Following this victory, an Egyptian Expeditionary Force advanced across the Sinai Peninsula, pushing Ottoman forces back in the Battle of Magdhaba in December and the Battle of Rafa on the border between the Egyptian Sinai Peninsula, Sinai and Ottoman Palestine in January 1917.

Russian armies generally had success in the Caucasus campaign. Enver Pasha, supreme commander of the Ottoman armed forces, was ambitious and dreamed of re-conquering central Asia and areas that had been lost to Russia previously. He was, however, a poor commander. He launched an offensive against the Russians in the Caucasus in December 1914 with 100,000 troops, insisting on a frontal attack against mountainous Russian positions in winter. He lost 86% of his force at the Battle of Sarikamish.

Further to the west, the Suez Canal was defended from Ottoman attacks in 1915 and 1916; in August, a German and Ottoman force was defeated at the Battle of Romani by the ANZAC Mounted Division and the 52nd (Lowland) Infantry Division. Following this victory, an Egyptian Expeditionary Force advanced across the Sinai Peninsula, pushing Ottoman forces back in the Battle of Magdhaba in December and the Battle of Rafa on the border between the Egyptian Sinai Peninsula, Sinai and Ottoman Palestine in January 1917.

Russian armies generally had success in the Caucasus campaign. Enver Pasha, supreme commander of the Ottoman armed forces, was ambitious and dreamed of re-conquering central Asia and areas that had been lost to Russia previously. He was, however, a poor commander. He launched an offensive against the Russians in the Caucasus in December 1914 with 100,000 troops, insisting on a frontal attack against mountainous Russian positions in winter. He lost 86% of his force at the Battle of Sarikamish.

The Ottoman Empire, with German support, invaded Persia (modern Iran) in December 1914 in an effort to cut off British and Russian access to petroleum reservoirs around Baku near the Caspian Sea. Persia, ostensibly neutral, had long been under the spheres of British and Russian influence. The Ottomans and Germans were aided by Kurds, Kurdish and Azerbaijanis, Azeri forces, together with a large number of major Iranian tribes, such as the Qashqai people, Qashqai, Tangestan County, Tangistanis, Lurs, and Khamseh, while the Russians and British had the support of Armenian and Assyrian forces. The Persian campaign (World War I), Persian campaign was to last until 1918 and end in failure for the Ottomans and their allies. However, the Russian withdrawal from the war in 1917 led to Armenian and Assyrian forces, who had hitherto inflicted a series of defeats upon the forces of the Ottomans and their allies, being cut off from supply lines, outnumbered, outgunned and isolated, forcing them to fight and flee towards British lines in northern Mesopotamia.

The Ottoman Empire, with German support, invaded Persia (modern Iran) in December 1914 in an effort to cut off British and Russian access to petroleum reservoirs around Baku near the Caspian Sea. Persia, ostensibly neutral, had long been under the spheres of British and Russian influence. The Ottomans and Germans were aided by Kurds, Kurdish and Azerbaijanis, Azeri forces, together with a large number of major Iranian tribes, such as the Qashqai people, Qashqai, Tangestan County, Tangistanis, Lurs, and Khamseh, while the Russians and British had the support of Armenian and Assyrian forces. The Persian campaign (World War I), Persian campaign was to last until 1918 and end in failure for the Ottomans and their allies. However, the Russian withdrawal from the war in 1917 led to Armenian and Assyrian forces, who had hitherto inflicted a series of defeats upon the forces of the Ottomans and their allies, being cut off from supply lines, outnumbered, outgunned and isolated, forcing them to fight and flee towards British lines in northern Mesopotamia.

General Nikolai Yudenich, Yudenich, the Russian commander from 1915 to 1916, drove the Turks out of most of the southern Caucasus with a string of victories. During the 1916 campaign, the Russians defeated the Turks in the Erzurum offensive, also Trebizond Campaign, occupying Trabzon. In 1917, Russian Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich of Russia (1856–1929), Grand Duke Nicholas assumed command of the Caucasus front. Nicholas planned a railway from Georgia within the Russian Empire, Russian Georgia to the conquered territories so that fresh supplies could be brought up for a new offensive in 1917. However, in March 1917 (February in the pre-revolutionary Russian calendar), the Tsar abdicated in the course of the February Revolution, and the Caucasus Army (Russian Empire, 1914–1917), Russian Caucasus Army began to fall apart.

The Arab Revolt, instigated by the Arab bureau of the British Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, Foreign Office, started June 1916 with the Battle of Mecca (1916), Battle of Mecca, led by Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca, Sharif Hussein of Mecca, and ended with the Ottoman surrender of Damascus. Fakhri Pasha, the Ottoman commander of Medina, resisted for more than two and half years during the siege of Medina before surrendering in January 1919.

The Senusiyya, Senussi tribe, along the border of Italian Libya and British Egypt, incited and armed by the Turks, waged a small-scale Guerrilla warfare, guerrilla war against Allied troops. The British were forced to dispatch 12,000 troops to oppose them in the Senussi campaign. Their rebellion was finally crushed in mid-1916.

Total Allied casualties on the Ottoman fronts amounted 650,000 men. Total Ottoman casualties were 725,000, with 325,000 dead and 400,000 wounded.

General Nikolai Yudenich, Yudenich, the Russian commander from 1915 to 1916, drove the Turks out of most of the southern Caucasus with a string of victories. During the 1916 campaign, the Russians defeated the Turks in the Erzurum offensive, also Trebizond Campaign, occupying Trabzon. In 1917, Russian Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich of Russia (1856–1929), Grand Duke Nicholas assumed command of the Caucasus front. Nicholas planned a railway from Georgia within the Russian Empire, Russian Georgia to the conquered territories so that fresh supplies could be brought up for a new offensive in 1917. However, in March 1917 (February in the pre-revolutionary Russian calendar), the Tsar abdicated in the course of the February Revolution, and the Caucasus Army (Russian Empire, 1914–1917), Russian Caucasus Army began to fall apart.

The Arab Revolt, instigated by the Arab bureau of the British Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, Foreign Office, started June 1916 with the Battle of Mecca (1916), Battle of Mecca, led by Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca, Sharif Hussein of Mecca, and ended with the Ottoman surrender of Damascus. Fakhri Pasha, the Ottoman commander of Medina, resisted for more than two and half years during the siege of Medina before surrendering in January 1919.

The Senusiyya, Senussi tribe, along the border of Italian Libya and British Egypt, incited and armed by the Turks, waged a small-scale Guerrilla warfare, guerrilla war against Allied troops. The British were forced to dispatch 12,000 troops to oppose them in the Senussi campaign. Their rebellion was finally crushed in mid-1916.

Total Allied casualties on the Ottoman fronts amounted 650,000 men. Total Ottoman casualties were 725,000, with 325,000 dead and 400,000 wounded.

Italian Front

Although Italy joined the Triple Alliance in 1882, a treaty with its traditional Austrian enemy was so controversial that subsequent governments denied its existence and the terms were only made public in 1915. This arose from Italian nationalism, nationalist designs on Austro-Hungarian territory in Trentino, the Austrian Littoral, Rijeka and Dalmatia, which were considered vital to secure the borders established in Third Italian War of Independence, 1866. In 1902, Rome secretly agreed with France to remain neutral if the latter was attacked by Germany, effectively nullifying its role in the Triple Alliance.

Although Italy joined the Triple Alliance in 1882, a treaty with its traditional Austrian enemy was so controversial that subsequent governments denied its existence and the terms were only made public in 1915. This arose from Italian nationalism, nationalist designs on Austro-Hungarian territory in Trentino, the Austrian Littoral, Rijeka and Dalmatia, which were considered vital to secure the borders established in Third Italian War of Independence, 1866. In 1902, Rome secretly agreed with France to remain neutral if the latter was attacked by Germany, effectively nullifying its role in the Triple Alliance.

When the war began in 1914, Italy argued the Triple Alliance was defensive in nature and it was not obliged to support an Austrian attack on Serbia. Opposition to joining the Central Powers increased when Turkey became a member in September, since in Italo-Turkish War, 1911 Italy had occupied Ottoman possessions in Italian Libya, Libya and the Dodecanese islands. To secure Italian neutrality, the Central Powers offered them the French protectorate of Tunisia, while in return for an immediate entry into the war, the Allies agreed to their demands for Austrian territory and sovereignty over the Dodecanese. Although they remained secret, these provisions were incorporated into the April 1915 Treaty of London (1915), Treaty of London; Italy joined the Triple Entente and on 23 May declared war on Austria-Hungary, followed by Germany fifteen months later.

The pre-1914 Italian army was the weakest in Europe, short of officers, trained men, adequate transport and modern weapons; by April 1915, some of these deficiencies had been remedied but it was still unprepared for the major offensive required by the Treaty of London. The advantage of superior numbers was offset by the difficult terrain; much of the fighting took place at altitudes of over 3000 metres in the Alps and Dolomites, where trench lines had to be cut through rock and ice and keeping troops supplied was a major challenge. These issues were exacerbated by unimaginative strategies and tactics. Between 1915 and 1917, the Italian commander, Luigi Cadorna, undertook Battles of the Isonzo, a series of frontal assaults along the Isonzo which made little progress and cost many lives; by the end of the war, total Italian combat deaths totalled around 548,000.

In the spring of 1916, the Austro-Hungarians counterattacked in Asiago in the ''Battle of Asiago, Strafexpedition'', but made little progress and were pushed by the Italians back to the Tyrol. Although an Italian corps occupied southern Albania during World War I, Albania in May 1916, their main focus was the Isonzo front which after the Battle of Doberdò, capture of Gorizia in August 1916 remained static until October 1917. After a combined Austro-German force won a major victory at Battle of Caporetto, Caporetto, Cadorna was replaced by Armando Diaz who retreated more than before holding positions along the Second Battle of the Piave River, Piave River. A second Austrian Second Battle of the Piave River, offensive was repulsed in June 1918 and by October it was clear the Central Powers had lost the war. On 24 October, Diaz launched the Battle of Vittorio Veneto and initially met stubborn resistance, but with Austria-Hungary collapsing, Hungarian divisions in Italy now demanded they be sent home. When this was granted, many others followed and the Imperial army disintegrated, the Italians taking over 300,000 prisoners. On 3November, the Armistice of Villa Giusti ended hostilities between Austria-Hungary and Italy which occupied Trieste and areas along the Adriatic Sea awarded to it in 1915.

When the war began in 1914, Italy argued the Triple Alliance was defensive in nature and it was not obliged to support an Austrian attack on Serbia. Opposition to joining the Central Powers increased when Turkey became a member in September, since in Italo-Turkish War, 1911 Italy had occupied Ottoman possessions in Italian Libya, Libya and the Dodecanese islands. To secure Italian neutrality, the Central Powers offered them the French protectorate of Tunisia, while in return for an immediate entry into the war, the Allies agreed to their demands for Austrian territory and sovereignty over the Dodecanese. Although they remained secret, these provisions were incorporated into the April 1915 Treaty of London (1915), Treaty of London; Italy joined the Triple Entente and on 23 May declared war on Austria-Hungary, followed by Germany fifteen months later.

The pre-1914 Italian army was the weakest in Europe, short of officers, trained men, adequate transport and modern weapons; by April 1915, some of these deficiencies had been remedied but it was still unprepared for the major offensive required by the Treaty of London. The advantage of superior numbers was offset by the difficult terrain; much of the fighting took place at altitudes of over 3000 metres in the Alps and Dolomites, where trench lines had to be cut through rock and ice and keeping troops supplied was a major challenge. These issues were exacerbated by unimaginative strategies and tactics. Between 1915 and 1917, the Italian commander, Luigi Cadorna, undertook Battles of the Isonzo, a series of frontal assaults along the Isonzo which made little progress and cost many lives; by the end of the war, total Italian combat deaths totalled around 548,000.

In the spring of 1916, the Austro-Hungarians counterattacked in Asiago in the ''Battle of Asiago, Strafexpedition'', but made little progress and were pushed by the Italians back to the Tyrol. Although an Italian corps occupied southern Albania during World War I, Albania in May 1916, their main focus was the Isonzo front which after the Battle of Doberdò, capture of Gorizia in August 1916 remained static until October 1917. After a combined Austro-German force won a major victory at Battle of Caporetto, Caporetto, Cadorna was replaced by Armando Diaz who retreated more than before holding positions along the Second Battle of the Piave River, Piave River. A second Austrian Second Battle of the Piave River, offensive was repulsed in June 1918 and by October it was clear the Central Powers had lost the war. On 24 October, Diaz launched the Battle of Vittorio Veneto and initially met stubborn resistance, but with Austria-Hungary collapsing, Hungarian divisions in Italy now demanded they be sent home. When this was granted, many others followed and the Imperial army disintegrated, the Italians taking over 300,000 prisoners. On 3November, the Armistice of Villa Giusti ended hostilities between Austria-Hungary and Italy which occupied Trieste and areas along the Adriatic Sea awarded to it in 1915.

Romanian participation

Despite secretly agreeing to support the Triple Alliance in 1883, Romania increasingly found itself at odds with the Central Powers over their support for Bulgaria in the 1912 to 1913 Balkan Wars and the status of ethnic Romanian communities in Kingdom of Hungary, Hungarian-controlled Transylvania, which comprised an estimated 2.8 million of the 5.0 million population. With the ruling elite split into pro-German and pro-Entente factions, Romania remained neutral in 1914, arguing like Italy that because Austria-Hungary had declared war on Serbia, it was under no obligation to join them. They maintained this position for the next two years, while allowing Germany and Austria to transport military supplies and advisors across Romanian territory. In September 1914, Russia had acknowledged Romanian rights to Austro-Hungarian territories including Transylvania and Banat, whose acquisition had widespread popular support, and Russian success against Austria led Romania to join the Entente in the August 1916 Treaty of Bucharest. Under the strategic plan known as Hypothesis Z, the Romanian army planned an offensive into Transylvania, while defending Southern Dobruja and Giurgiu County, Giurgiu against a possible Bulgarian counterattack. On 27 August 1916, they Battle of Transylvania, attacked Transylvania and occupied substantial parts of the province before being driven back by the recently formed 9th Army (German Empire), German 9th Army, led by former Chief of Staff Falkenhayn. A combined German-Bulgarian-Turkish offensive captured Dobruja and Giurgiu, although the bulk of the Romanian army managed to escape encirclement and retreated to Bucharest, which Battle of Bucharest, surrendered to the Central Powers on 6 December 1916. Approximately 16% of the pre-war Austro-Hungarian population consisted of ethnic Romanians, whose loyalty faded as the war progressed; by 1917, they made up more than 50% of the 300,000 deserters from the Imperial army. Prisoners of war held by the Russian Empire formed the Romanian Volunteer Corps in Russia, Romanian Volunteer Corps who were repatriated to Romania in 1917. Many fought in the battles of Răcoasa, Mărăști, Mărășești and Oituz, where with Russian support the Romanian army managed to defeat an offensive by the Central Powers and even take back some territory. Left isolated after the October Revolution forced Russia out of the war, Romania signed an armistice on 9 December 1917. Shortly afterwards, fighting broke out in the adjacent Russian territory of Bessarabia between Bolsheviks and Romanian nationalists, who requested military assistance from their compatriots. Following their intervention, the independent Moldavian Democratic Republic was formed in February 1918, which voted for union with Romania on 27 March. On 7 May 1918 Romania signed the Treaty of Bucharest (1918), Treaty of Bucharest with the Central Powers, which recognised Romanian sovereignty over Bessarabia in return for ceding control of passes in the Carpathian Mountains to Austria-Hungary and granting oil concessions to Germany. Although approved by Parliament of Romania, Parliament, Ferdinand I of Romania, Ferdinand I refused to sign the treaty, hoping for an Allied victory; Romania re-entered the war on 10 November 1918 on the side of the Allies and the Treaty of Bucharest was formally annulled by the Armistice of 11 November 1918. Between 1914 and 1918, an estimated 400,000 to 600,000 ethnic Romanians served with the Austro-Hungarian army, of whom up to 150,000 were killed in action; total military and civilian deaths within contemporary Romanian borders are estimated at 748,000.

On 7 May 1918 Romania signed the Treaty of Bucharest (1918), Treaty of Bucharest with the Central Powers, which recognised Romanian sovereignty over Bessarabia in return for ceding control of passes in the Carpathian Mountains to Austria-Hungary and granting oil concessions to Germany. Although approved by Parliament of Romania, Parliament, Ferdinand I of Romania, Ferdinand I refused to sign the treaty, hoping for an Allied victory; Romania re-entered the war on 10 November 1918 on the side of the Allies and the Treaty of Bucharest was formally annulled by the Armistice of 11 November 1918. Between 1914 and 1918, an estimated 400,000 to 600,000 ethnic Romanians served with the Austro-Hungarian army, of whom up to 150,000 were killed in action; total military and civilian deaths within contemporary Romanian borders are estimated at 748,000.

Eastern Front

Initial actions

As previously agreed with France, Russian plans at the start of the war were to simultaneously advance into Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, Austrian Galicia and East Prussia as soon as possible. Although their Battle of Galicia, attack on Galicia was largely successful, and the invasions achieved their aim of forcing Germany to divert troops from the Western Front, the speed of mobilisation meant they did so without much of their heavy equipment and support functions. These weaknesses contributed to Russian defeats at Battle of Tannenberg, Tannenberg and the First Battle of the Masurian Lakes, Masurian Lakes in August and September 1914, forcing them to withdraw from East Prussia with heavy losses. By spring 1915, they had also retreated from Galicia, and the May 1915 Gorlice–Tarnów offensive then allowed the Central Powers to invade Congress Poland, Russian-occupied Poland. On 5August, the loss of Warsaw forced the Russians to abandon their Polish territories.

Despite the successful June 1916 Brusilov offensive against the Austrians in eastern Galicia, shortages of supplies, heavy losses and command failures prevented the Russians from fully exploiting their victory. However, it was one of the most significant and impactful offensives of the war, diverting German resources from

As previously agreed with France, Russian plans at the start of the war were to simultaneously advance into Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, Austrian Galicia and East Prussia as soon as possible. Although their Battle of Galicia, attack on Galicia was largely successful, and the invasions achieved their aim of forcing Germany to divert troops from the Western Front, the speed of mobilisation meant they did so without much of their heavy equipment and support functions. These weaknesses contributed to Russian defeats at Battle of Tannenberg, Tannenberg and the First Battle of the Masurian Lakes, Masurian Lakes in August and September 1914, forcing them to withdraw from East Prussia with heavy losses. By spring 1915, they had also retreated from Galicia, and the May 1915 Gorlice–Tarnów offensive then allowed the Central Powers to invade Congress Poland, Russian-occupied Poland. On 5August, the loss of Warsaw forced the Russians to abandon their Polish territories.

Despite the successful June 1916 Brusilov offensive against the Austrians in eastern Galicia, shortages of supplies, heavy losses and command failures prevented the Russians from fully exploiting their victory. However, it was one of the most significant and impactful offensives of the war, diverting German resources from Central Powers peace overtures

On 12 December 1916, after ten brutal months of the Battle of Verdun and a Romania in World War I#The counteroffensive of the Central Powers, successful offensive against Romania, Germany attempted to negotiate a peace with the Allies. However, this attempt was rejected out of hand as a "duplicitous war ruse".

Soon after, US president Woodrow Wilson attempted to intervene as a peacemaker, asking in a note for both sides to state their demands and start negotiations. David Lloyd George, Lloyd George's War Cabinet considered the German offer to be a ploy to create divisions amongst the Allies. After initial outrage and much deliberation, they took Wilson's note as a separate effort, signalling that the United States was on the verge of entering the war against Germany following the "submarine outrages". While the Allies debated a response to Wilson's offer, the Germans chose to rebuff it in favour of "a direct exchange of views". Learning of the German response, the Allied governments were free to make clear demands in their response of 14 January. They sought restoration of damages, the evacuation of occupied territories, reparations for France, Russia and Romania, and a recognition of the principle of nationalities. This included the liberation of Italians, Slavs, Romanians, Czecho-Slovaks, and the creation of a "free and united Poland". On the question of security, the Allies sought guarantees that would prevent or limit future wars, complete with sanctions, as a condition of any peace settlement. The negotiations failed and the Entente powers rejected the German offer on the grounds that Germany had not put forward any specific proposals.

On 12 December 1916, after ten brutal months of the Battle of Verdun and a Romania in World War I#The counteroffensive of the Central Powers, successful offensive against Romania, Germany attempted to negotiate a peace with the Allies. However, this attempt was rejected out of hand as a "duplicitous war ruse".

Soon after, US president Woodrow Wilson attempted to intervene as a peacemaker, asking in a note for both sides to state their demands and start negotiations. David Lloyd George, Lloyd George's War Cabinet considered the German offer to be a ploy to create divisions amongst the Allies. After initial outrage and much deliberation, they took Wilson's note as a separate effort, signalling that the United States was on the verge of entering the war against Germany following the "submarine outrages". While the Allies debated a response to Wilson's offer, the Germans chose to rebuff it in favour of "a direct exchange of views". Learning of the German response, the Allied governments were free to make clear demands in their response of 14 January. They sought restoration of damages, the evacuation of occupied territories, reparations for France, Russia and Romania, and a recognition of the principle of nationalities. This included the liberation of Italians, Slavs, Romanians, Czecho-Slovaks, and the creation of a "free and united Poland". On the question of security, the Allies sought guarantees that would prevent or limit future wars, complete with sanctions, as a condition of any peace settlement. The negotiations failed and the Entente powers rejected the German offer on the grounds that Germany had not put forward any specific proposals.

1917; Timeline of Major Developments

March to November 1917; Russian Revolution

By the end of 1916, Russian casualties totalled nearly five million killed, wounded or captured, with major urban areas affected by food shortages and high prices. In March 1917, Tsar Nicholas ordered the military to forcibly suppress a wave of strikes in Saint Petersburg, Petrograd but the troops refused to fire on the crowds. Revolutionaries set up the Petrograd Soviet and fearing a left-wing takeover, the State Duma forced Nicholas to abdicate and established the Russian Provisional Government, which confirmed Russia's willingness to continue the war. However, the Petrograd Soviet refused to disband, creating Dual power, competing power centres and caused confusion and chaos, with frontline soldiers becoming increasingly demoralised and unwilling to fight on. In the summer of 1917 aApril 1917: the United States enters the war

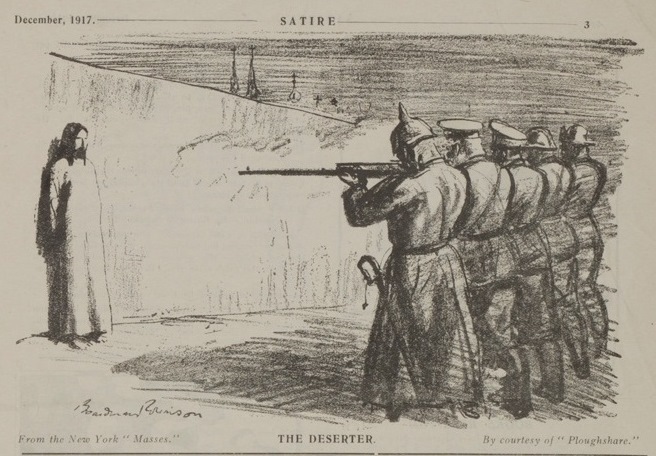

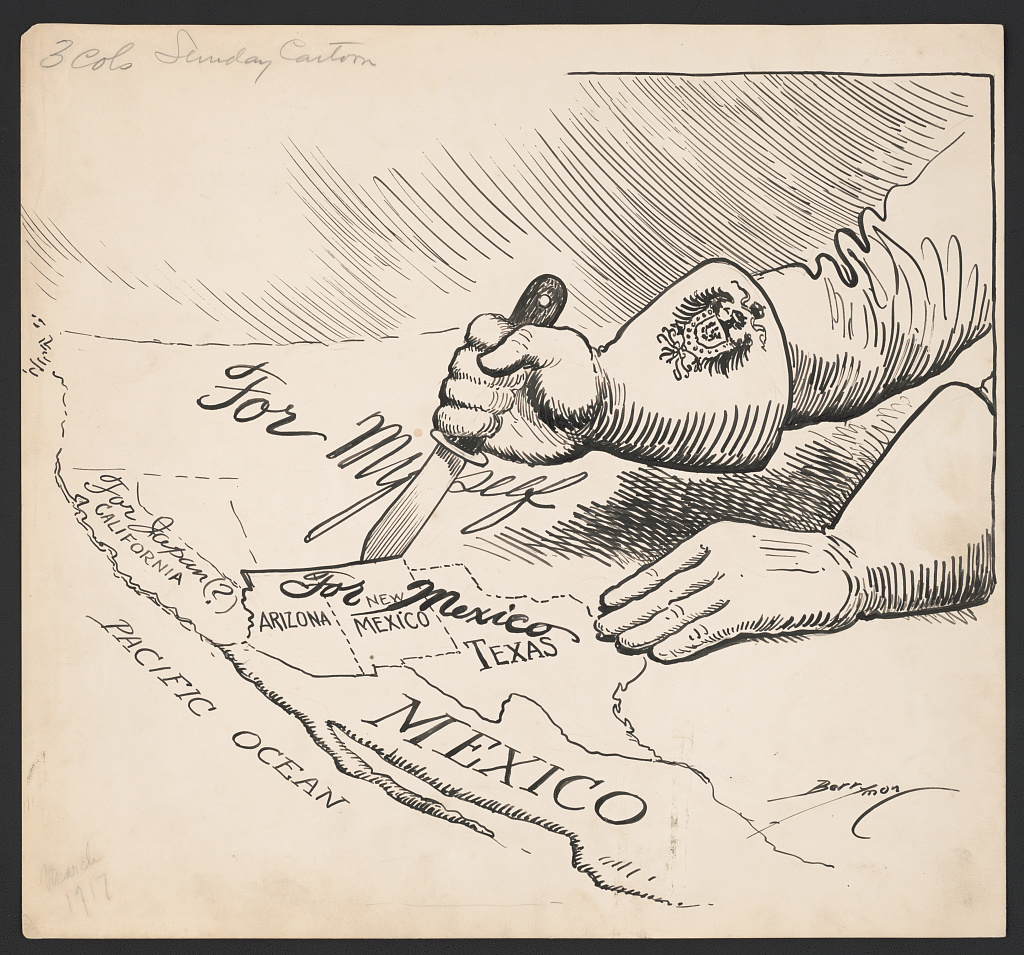

The United States was a major supplier of war materiel to the Allies but remained neutral in 1914; many opposed the idea of involvement in "foreign wars", while German Americans made up over 10% of the total population in 1913. On 7May 1915, 128 Americans died when the British Passenger ship Sinking of the RMS Lusitania, ''Lusitania'' was sunk by a German SM U-20 (Germany), submarine. President Woodrow Wilson demanded an apology and warned the United States would not tolerate unrestricted submarine warfare but refused to be drawn into the war. When more Americans died after the sinking of SS Arabic (1902), SS Arabic in August, Bethman-Hollweg ordered an end to such attacks. Wilson argued he was "too proud to fight", although former president Theodore Roosevelt denounced the idea of "setting a spiritual example [to others] by sitting idle, uttering cheap platitudes and picking up their trade". Despite growing pro-war sentiment, Wilson was narrowly re-elected as president in 1916 United States presidential election, 1916. By the end of 1916, the British naval blockade was causing serious shortages in Germany and Wilhelm approved the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare on 1 February 1917. While the German government recognised this action was likely to bring America into the war, the navy claimed they could starve Britain into submission in less than six months. The military position also appeared stable, at least for the foreseeable future. Despite heavy losses at Verdun and the Somme during 1916, withdrawal to the newly created Hindenburg Line would enable the ''Westheer'' to conserve its troops, while it was clear Russia was on the brink of revolution. The combination meant Germany was willing to gamble it could force the Allies to make peace before the US could intervene in any meaningful way. Although Wilson severed diplomatic relations on 2 February, he was reluctant to start hostilities without overwhelming public support. On 24 February, he was presented with the Zimmermann Telegram; drafted in January by German Foreign Secretary Arthur Zimmermann, it was intercepted and decoded by British intelligence, who shared it with their American counterparts. Already financing Russian The most significant factor in creating the support Wilson needed was the German submarine offensive, which not only cost American lives, but paralysed trade as ships were reluctant to put to sea. This caused food shortages in cities along the East Coast of the United States, East Coast and on 22 March, United States Congress, Congress approved the arming of merchant ships. Now committed to war, in his speech to Congress on 2 April Wilson presented it as a crusade "against human greed and folly, against Germany, and for justice, peace and civilisation". On 6 April, Congress United States declaration of war on Germany (1917), declared war on Germany as an "Associated Power" of the Allies. At this stage they were not at war with the other Central Powers.

The United States Navy sent a United States Battleship Division Nine (World War I), battleship group to Scapa Flow to join the Grand Fleet and provided convoy escorts. In April 1917, the United States Army had fewer than 300,000 men, including Army National Guard, National Guard units, compared to British and French armies of 4.1 and 8.3 million respectively. The Selective Service Act of 1917 drafted 2.8 million men, although training and equipping such numbers was a huge logistical challenge. By June 1918, over 667,000 members of the American Expeditionary Forces, or AEF, had been transported to France, a figure which reached 2 million by the end of November. However, American tactical doctrine was still based on pre-1914 principles, a world away from the combined arms approach used by the French and British in 1918. US commanders were initially slow to accept such ideas, leading to heavy casualties and it was not until the last month of the war that these failings were rectified.

Despite his conviction Germany must be defeated, Wilson went to war to ensure the US played a leading role in shaping the peace, which meant preserving the AEF as a separate military force, rather than being absorbed into British or French units as his Allies wanted. He was strongly supported by AEF commander General John J. Pershing, a proponent of pre-1914 "open warfare" who considered the French and British emphasis on artillery as misguided and incompatible with American "offensive spirit". Much to the frustration of his Allies, who had suffered heavy losses in 1917, he insisted on retaining control of American troops and refused to commit them to the front line until able to operate as independent units. As a result, the first significant US involvement was the Meuse–Argonne offensive in late September 1918.

The most significant factor in creating the support Wilson needed was the German submarine offensive, which not only cost American lives, but paralysed trade as ships were reluctant to put to sea. This caused food shortages in cities along the East Coast of the United States, East Coast and on 22 March, United States Congress, Congress approved the arming of merchant ships. Now committed to war, in his speech to Congress on 2 April Wilson presented it as a crusade "against human greed and folly, against Germany, and for justice, peace and civilisation". On 6 April, Congress United States declaration of war on Germany (1917), declared war on Germany as an "Associated Power" of the Allies. At this stage they were not at war with the other Central Powers.

The United States Navy sent a United States Battleship Division Nine (World War I), battleship group to Scapa Flow to join the Grand Fleet and provided convoy escorts. In April 1917, the United States Army had fewer than 300,000 men, including Army National Guard, National Guard units, compared to British and French armies of 4.1 and 8.3 million respectively. The Selective Service Act of 1917 drafted 2.8 million men, although training and equipping such numbers was a huge logistical challenge. By June 1918, over 667,000 members of the American Expeditionary Forces, or AEF, had been transported to France, a figure which reached 2 million by the end of November. However, American tactical doctrine was still based on pre-1914 principles, a world away from the combined arms approach used by the French and British in 1918. US commanders were initially slow to accept such ideas, leading to heavy casualties and it was not until the last month of the war that these failings were rectified.

Despite his conviction Germany must be defeated, Wilson went to war to ensure the US played a leading role in shaping the peace, which meant preserving the AEF as a separate military force, rather than being absorbed into British or French units as his Allies wanted. He was strongly supported by AEF commander General John J. Pershing, a proponent of pre-1914 "open warfare" who considered the French and British emphasis on artillery as misguided and incompatible with American "offensive spirit". Much to the frustration of his Allies, who had suffered heavy losses in 1917, he insisted on retaining control of American troops and refused to commit them to the front line until able to operate as independent units. As a result, the first significant US involvement was the Meuse–Argonne offensive in late September 1918.

April to June; Nivelle Offensive and French Army mutinies

Verdun cost the French nearly 400,000 casualties, while the horrific conditions severely impacted morale, leading to a number of incidents of indiscipline. Although relatively minor, they reflected a belief among the rank and file that their sacrifices were not appreciated by their government or senior officers. Combatants on both sides claimed the battle was the most psychologically exhausting of the entire war; recognising this, Philippe Pétain frequently rotated divisions, a process known as the noria system. While this ensured units were withdrawn before their ability to fight was significantly eroded, it meant a high proportion of the French army was affected by the battle. By the beginning of 1917, morale was brittle, even in divisions with good combat records.

In December 1916, Robert Nivelle replaced Pétain as commander of French armies on the Western Front and began planning a Nivelle offensive, spring attack in Champagne (province), Champagne, part of a joint Franco-British operation. Nivelle claimed the capture of his main objective, the Chemin des Dames, would achieve a massive breakthrough and cost no more than 15,000 casualties. Poor security meant German intelligence was well informed on tactics and timetables, but despite this, when the attack began on 16 April the French made substantial gains, before being brought to a halt by the newly built and extremely strong defences of the Hindenburg Line. Nivelle persisted with frontal assaults and by 25 April the French had suffered nearly 135,000 casualties, including 30,000 dead, most incurred in the first two days.

Concurrent British attacks at Battle of Arras (1917), Arras were more successful, although ultimately of little strategic value. Operating as a separate unit for the first time, the Canadian Corps capture of Battle of Vimy Ridge, Vimy Ridge during the battle is viewed by many Canadians as a defining moment in creating a sense of national identity. Although Nivelle continued the offensive, on 3 May the 21st Infantry Division (France), 21st Division, which had been involved in some of the heaviest fighting at Verdun, refused orders to go into battle, initiating the 1917 French Army mutinies, French Army mutinies; within days, acts of "collective indiscipline" had spread to 54 divisions, while over 20,000 deserted. Unrest was almost entirely confined to the infantry, whose demands were largely non-political, including better economic support for families at home, and regular periods of leave, which Nivelle had ended.

Verdun cost the French nearly 400,000 casualties, while the horrific conditions severely impacted morale, leading to a number of incidents of indiscipline. Although relatively minor, they reflected a belief among the rank and file that their sacrifices were not appreciated by their government or senior officers. Combatants on both sides claimed the battle was the most psychologically exhausting of the entire war; recognising this, Philippe Pétain frequently rotated divisions, a process known as the noria system. While this ensured units were withdrawn before their ability to fight was significantly eroded, it meant a high proportion of the French army was affected by the battle. By the beginning of 1917, morale was brittle, even in divisions with good combat records.

In December 1916, Robert Nivelle replaced Pétain as commander of French armies on the Western Front and began planning a Nivelle offensive, spring attack in Champagne (province), Champagne, part of a joint Franco-British operation. Nivelle claimed the capture of his main objective, the Chemin des Dames, would achieve a massive breakthrough and cost no more than 15,000 casualties. Poor security meant German intelligence was well informed on tactics and timetables, but despite this, when the attack began on 16 April the French made substantial gains, before being brought to a halt by the newly built and extremely strong defences of the Hindenburg Line. Nivelle persisted with frontal assaults and by 25 April the French had suffered nearly 135,000 casualties, including 30,000 dead, most incurred in the first two days.

Concurrent British attacks at Battle of Arras (1917), Arras were more successful, although ultimately of little strategic value. Operating as a separate unit for the first time, the Canadian Corps capture of Battle of Vimy Ridge, Vimy Ridge during the battle is viewed by many Canadians as a defining moment in creating a sense of national identity. Although Nivelle continued the offensive, on 3 May the 21st Infantry Division (France), 21st Division, which had been involved in some of the heaviest fighting at Verdun, refused orders to go into battle, initiating the 1917 French Army mutinies, French Army mutinies; within days, acts of "collective indiscipline" had spread to 54 divisions, while over 20,000 deserted. Unrest was almost entirely confined to the infantry, whose demands were largely non-political, including better economic support for families at home, and regular periods of leave, which Nivelle had ended.

Although the vast majority remained willing to defend their own lines, they refused to participate in offensive action, reflecting a complete breakdown of trust in the army leadership. Nivelle was removed from command on 15 May and replaced by Pétain, who resisted demands for drastic punishment and set about restoring morale by improving conditions. While exact figures are still debated, only 27 men were actually executed, with another 3,000 sentenced to periods of imprisonment; however, the psychological effects were long-lasting, one veteran commenting "Pétain has purified the unhealthy atmosphere...but they have ruined the heart of the French soldier".

The last large-scale offensive of this period was a British attack (with French support) at Battle of Passchendaele, Passchendaele (July–November 1917). This offensive opened with great promise for the Allies, before bogging down in the October mud. Casualties, though disputed, were roughly equal, at some 200,000–400,000 per side.

The victory of the Central Powers at the Battle of Caporetto led the Allies to convene the Rapallo and Peschiera conferences, Rapallo conference at which they formed the Supreme War Council to co-ordinate planning. Previously, British and French armies had operated under separate commands.

In December, the Central Powers signed an armistice with Russia, thus freeing large numbers of German troops for use in the west. With German reinforcements and new American troops pouring in, the outcome was to be decided on the Western Front. The Central Powers knew that they could not win a protracted war, but they held high hopes for success based on a final quick offensive. Furthermore, both sides became increasingly fearful of social unrest and revolution in Europe. Thus, both sides urgently sought a decisive victory.

In 1917, Emperor Charles I of Austria secretly attempted separate peace negotiations with Clemenceau, through his wife's brother Prince Sixtus of Bourbon-Parma, Sixtus in Belgium as an intermediary, without the knowledge of Germany. Italy opposed the proposals. When the negotiations failed, his attempt was revealed to Germany, resulting in a diplomatic catastrophe.

Although the vast majority remained willing to defend their own lines, they refused to participate in offensive action, reflecting a complete breakdown of trust in the army leadership. Nivelle was removed from command on 15 May and replaced by Pétain, who resisted demands for drastic punishment and set about restoring morale by improving conditions. While exact figures are still debated, only 27 men were actually executed, with another 3,000 sentenced to periods of imprisonment; however, the psychological effects were long-lasting, one veteran commenting "Pétain has purified the unhealthy atmosphere...but they have ruined the heart of the French soldier".

The last large-scale offensive of this period was a British attack (with French support) at Battle of Passchendaele, Passchendaele (July–November 1917). This offensive opened with great promise for the Allies, before bogging down in the October mud. Casualties, though disputed, were roughly equal, at some 200,000–400,000 per side.

The victory of the Central Powers at the Battle of Caporetto led the Allies to convene the Rapallo and Peschiera conferences, Rapallo conference at which they formed the Supreme War Council to co-ordinate planning. Previously, British and French armies had operated under separate commands.

In December, the Central Powers signed an armistice with Russia, thus freeing large numbers of German troops for use in the west. With German reinforcements and new American troops pouring in, the outcome was to be decided on the Western Front. The Central Powers knew that they could not win a protracted war, but they held high hopes for success based on a final quick offensive. Furthermore, both sides became increasingly fearful of social unrest and revolution in Europe. Thus, both sides urgently sought a decisive victory.

In 1917, Emperor Charles I of Austria secretly attempted separate peace negotiations with Clemenceau, through his wife's brother Prince Sixtus of Bourbon-Parma, Sixtus in Belgium as an intermediary, without the knowledge of Germany. Italy opposed the proposals. When the negotiations failed, his attempt was revealed to Germany, resulting in a diplomatic catastrophe.

Ottoman Empire conflict, 1917–1918

In March and April 1917, at the First Battle of Gaza, First and Second Battle of Gaza, Second Battles of Gaza, German and Ottoman forces stopped the advance of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, which had begun in August 1916 at the Battle of Romani.

At the end of October, the Sinai and Palestine campaign resumed, when General Edmund Allenby, 1st Viscount Allenby, Edmund Allenby's XX Corps (United Kingdom), XXth Corps, XXI Corps (United Kingdom), XXI Corps and Desert Mounted Corps won the Battle of Beersheba (1917), Battle of Beersheba. Two Ottoman armies were defeated a few weeks later at the Battle of Mughar Ridge and, early in December, Jerusalem was captured following another Ottoman defeat at the Battle of Jerusalem. About this time, Friedrich Freiherr Kress von Kressenstein was relieved of his duties as the Eighth Army's commander, replaced by Cevat Çobanlı, Djevad Pasha, and a few months later the commander of the Military of the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman Army in Palestine, Erich von Falkenhayn, was replaced by Otto Liman von Sanders.

In early 1918, the front line was Capture of Jericho, extended and the British occupation of the Jordan Valley, Jordan Valley was occupied, following the First Transjordan attack on Amman, First Transjordan and the Second Transjordan attack on Shunet Nimrin and Es Salt, Second Transjordan attacks by British Empire forces in March and April 1918. In March, most of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force's British infantry and Yeomanry cavalry were sent to the Western Front as a consequence of the Spring Offensive. They were replaced by Indian Army units. During several months of reorganisation and training of the summer, a Sinai and Palestine campaign#Jordan Valley operations, number of attacks were carried out on sections of the Ottoman front line. These pushed the front line north to more advantageous positions for the Entente in preparation for an attack and to acclimatise the newly arrived Indian Army infantry. It was not until the middle of September that the integrated force was ready for large-scale operations.

In March and April 1917, at the First Battle of Gaza, First and Second Battle of Gaza, Second Battles of Gaza, German and Ottoman forces stopped the advance of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, which had begun in August 1916 at the Battle of Romani.

At the end of October, the Sinai and Palestine campaign resumed, when General Edmund Allenby, 1st Viscount Allenby, Edmund Allenby's XX Corps (United Kingdom), XXth Corps, XXI Corps (United Kingdom), XXI Corps and Desert Mounted Corps won the Battle of Beersheba (1917), Battle of Beersheba. Two Ottoman armies were defeated a few weeks later at the Battle of Mughar Ridge and, early in December, Jerusalem was captured following another Ottoman defeat at the Battle of Jerusalem. About this time, Friedrich Freiherr Kress von Kressenstein was relieved of his duties as the Eighth Army's commander, replaced by Cevat Çobanlı, Djevad Pasha, and a few months later the commander of the Military of the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman Army in Palestine, Erich von Falkenhayn, was replaced by Otto Liman von Sanders.

In early 1918, the front line was Capture of Jericho, extended and the British occupation of the Jordan Valley, Jordan Valley was occupied, following the First Transjordan attack on Amman, First Transjordan and the Second Transjordan attack on Shunet Nimrin and Es Salt, Second Transjordan attacks by British Empire forces in March and April 1918. In March, most of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force's British infantry and Yeomanry cavalry were sent to the Western Front as a consequence of the Spring Offensive. They were replaced by Indian Army units. During several months of reorganisation and training of the summer, a Sinai and Palestine campaign#Jordan Valley operations, number of attacks were carried out on sections of the Ottoman front line. These pushed the front line north to more advantageous positions for the Entente in preparation for an attack and to acclimatise the newly arrived Indian Army infantry. It was not until the middle of September that the integrated force was ready for large-scale operations.

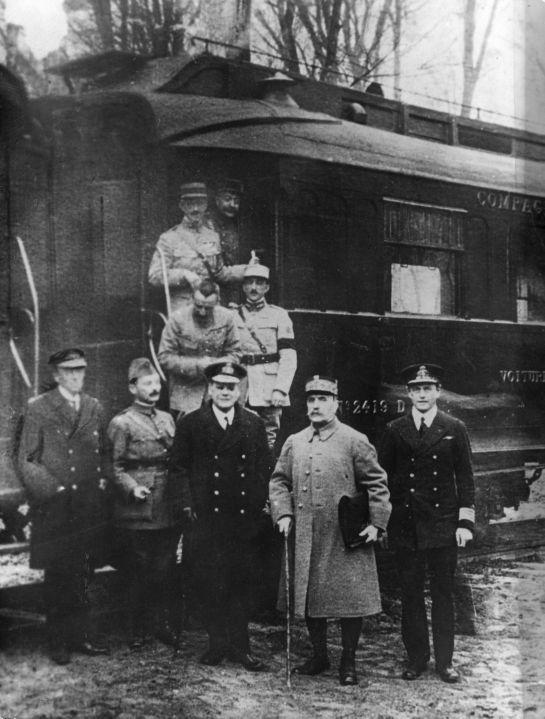

The reorganised Egyptian Expeditionary Force, with an additional mounted division, broke Ottoman forces at the Battle of Megiddo (1918), Battle of Megiddo in September 1918. In two days, the British and Indian infantry, supported by a creeping barrage, broke the Ottoman front line and captured the headquarters of the Eighth Army (Ottoman Empire) at Battle of Tulkarm, Tulkarm, the continuous trench lines at Battle of Tabsor, Tabsor, Battle of Arara, Arara, and the Seventh Army (Ottoman Empire) headquarters at Battle of Nablus (1918), Nablus. The Desert Mounted Corps rode through the break in the front line created by the infantry. During virtually continuous operations by Australian Light Horse, British mounted Yeomanry, Indian Lancers, and New Zealand Mounted infantry, Mounted Rifle brigades in the Jezreel Valley, they captured Battle of Nazareth, Nazareth, Capture of Afulah and Beisan, Afulah and Beisan, Capture of Jenin, Jenin, along with Battle of Haifa (1918), Haifa on the Mediterranean coast and Daraa east of the Jordan River on the Hejaz railway. Battle of Samakh, Samakh and Tiberias on the Sea of Galilee were captured on the way northwards to Damascus. Meanwhile, Third Transjordan attack, Chaytor's Force of Australian light horse, New Zealand mounted rifles, Indian, British West Indies and Jewish infantry captured the crossings of the Jordan River, Al-Salt, Es Salt, Amman and at Ziza most of the Fourth Army (Ottoman Empire). The Armistice of Mudros, signed at the end of October, ended hostilities with the Ottoman Empire when fighting was continuing north of Aleppo.