William Withering on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

William Withering FRS (17 March 1741 – 6 October 1799) was an English

Born in England, Withering attended Edinburgh Medical School from 1762 to 1766. In 1767 he started as a consultant at Stafford Royal Infirmary. He married Helena Cookes (an amateur botanical illustrator, and a former patient of his) in 1772; they had three children (the first, Helena was born in 1775 but died a few days later, William was born in 1776, and Charlotte in 1778). In 1775 he was appointed physician to

Born in England, Withering attended Edinburgh Medical School from 1762 to 1766. In 1767 he started as a consultant at Stafford Royal Infirmary. He married Helena Cookes (an amateur botanical illustrator, and a former patient of his) in 1772; they had three children (the first, Helena was born in 1775 but died a few days later, William was born in 1776, and Charlotte in 1778). In 1775 he was appointed physician to

/ref> During the Birmingham riots of 1791 (in which

In 1776, he published ''The botanical arrangement of all the vegetables naturally growing in Great Britain'', an early and influential British

In 1776, he published ''The botanical arrangement of all the vegetables naturally growing in Great Britain'', an early and influential British

In reality "Mother Hutton" was created in 1928 in an illustration by William Meade Prince as part of an advertising campaign by Parke-Davis who marketed digitalis preparations. There is no mention of a Mother Hutton in Withering's works or anyone else's and no mention of him meeting any old woman directly. In his account he states that he is merely asked to comment on a family recipe that was originally an old woman's receipt or recipe (that she had long kept secret) by a colleague. Since 1928, Mother Hutton's status has grown from being an image in an advertising poster to an acclaimed wise woman, herbalist, pharmacist and medical practitioner in Shropshire who was cheated out of her true recognition by Dr. Withering's unscrupulous methods. The story often written around this is also totally apocryphal. Withering was in fact informed of the Brasenose College, Oxford case by one of his medical colleagues Dr. Ash at Birmingham Hospital and the Dean was treated with digitalis root not leaves. The myth of Mother Hutton and how Withering chased her around Shropshire has been created by authors not going back to primary sources but instead copying and then embellishing the unreferenced work of others. See "Withering and The Foxglove; the making of a myth" by D.M. Krikler (British Heart Journal, 1985, 54: 256–257). In Withering's ''Account of the Foxglove'' printed in 1785 Withering mentions seven different occasions when foxglove was brought to his attention. Recognising that foxglove was the active ingredient in a family recipe (that was long kept secret by an old woman in Shropshire) would not have been difficult with his expert botanical knowledge. Withering had first published his ''Botanical Arrangement'' in 1776 and in it suggested foxglove deserved looking at in more detail. Erasmus Darwin tried to take the credit for foxglove and failed. Erasmus Darwin then attempted to try and discredit Withering behind the scenes with the unwitting help of his son Robert having earlier used the thesis of his dead son Charles to try and establish priority. Charles Darwin in fact had been friendly with Withering (as had Robert) and had talked in Edinburgh University about Withering's experiments with foxglove. Erasmus Darwin was probably jealous that Withering had become the most famous and sought-after doctor outside London and that Withering's English Botanical Arrangement became the standard reference source and far exceeded the botanical publications of Erasmus (all published semi-anonymously) in popularity. Withering's Botanical Arrangement, although now almost forgotten, became the standard reference for English Botany for almost the next 100 years.

In reality "Mother Hutton" was created in 1928 in an illustration by William Meade Prince as part of an advertising campaign by Parke-Davis who marketed digitalis preparations. There is no mention of a Mother Hutton in Withering's works or anyone else's and no mention of him meeting any old woman directly. In his account he states that he is merely asked to comment on a family recipe that was originally an old woman's receipt or recipe (that she had long kept secret) by a colleague. Since 1928, Mother Hutton's status has grown from being an image in an advertising poster to an acclaimed wise woman, herbalist, pharmacist and medical practitioner in Shropshire who was cheated out of her true recognition by Dr. Withering's unscrupulous methods. The story often written around this is also totally apocryphal. Withering was in fact informed of the Brasenose College, Oxford case by one of his medical colleagues Dr. Ash at Birmingham Hospital and the Dean was treated with digitalis root not leaves. The myth of Mother Hutton and how Withering chased her around Shropshire has been created by authors not going back to primary sources but instead copying and then embellishing the unreferenced work of others. See "Withering and The Foxglove; the making of a myth" by D.M. Krikler (British Heart Journal, 1985, 54: 256–257). In Withering's ''Account of the Foxglove'' printed in 1785 Withering mentions seven different occasions when foxglove was brought to his attention. Recognising that foxglove was the active ingredient in a family recipe (that was long kept secret by an old woman in Shropshire) would not have been difficult with his expert botanical knowledge. Withering had first published his ''Botanical Arrangement'' in 1776 and in it suggested foxglove deserved looking at in more detail. Erasmus Darwin tried to take the credit for foxglove and failed. Erasmus Darwin then attempted to try and discredit Withering behind the scenes with the unwitting help of his son Robert having earlier used the thesis of his dead son Charles to try and establish priority. Charles Darwin in fact had been friendly with Withering (as had Robert) and had talked in Edinburgh University about Withering's experiments with foxglove. Erasmus Darwin was probably jealous that Withering had become the most famous and sought-after doctor outside London and that Withering's English Botanical Arrangement became the standard reference source and far exceeded the botanical publications of Erasmus (all published semi-anonymously) in popularity. Withering's Botanical Arrangement, although now almost forgotten, became the standard reference for English Botany for almost the next 100 years.

Withering was an enthusiastic chemist and geologist. He conducted a series of experiments on ''Terra Ponderosa'', a heavy ore from Cumberland, England. He deduced that it contained a hitherto undescribed element which he was unable to characterise. It was later shown to be

Withering was an enthusiastic chemist and geologist. He conducted a series of experiments on ''Terra Ponderosa'', a heavy ore from Cumberland, England. He deduced that it contained a hitherto undescribed element which he was unable to characterise. It was later shown to be

/ref> The

Wellington News

July 2011

This list is drawn from Sheldon, 2004:Sheldon, Peter (2004). ''The Life and Times of William Withering: His Work, His Legacy''.

*1766 Dissertation on ''angina gangrenosa''

*1773 "Experiments on different kinds of Marle found in Staffordshire" ''Phil Trans. 63: 161-2''

*

*

*1779 "An account of the scarlet fever and sore throat, or scarlatina; particularly as it appeared at Birmingham in the year 1778" Publ Cadell London

*1782 "An analysis of two mineral substance, vz. the Rowley rag-stone and the toad stone" ''Phil Trans 72: 327-36''

*1783 "Outlines of mineralogy" Publ Cadell, London (a translation of Bergmann's Latin original)

*1784 "Experiments and observations on the terra ponderosa" Phil trans 74: 293-311

*1785 "An account of the foxglove and some of its medical uses; with practical remarks on the dropsy, and some other diseases" Publ Swinney, Birmingham

*1787 "A botanical arrangement of British plants..." 2nd ed. Publ Swinney, London

*1788 Letter to

This list is drawn from Sheldon, 2004:Sheldon, Peter (2004). ''The Life and Times of William Withering: His Work, His Legacy''.

*1766 Dissertation on ''angina gangrenosa''

*1773 "Experiments on different kinds of Marle found in Staffordshire" ''Phil Trans. 63: 161-2''

*

*

*1779 "An account of the scarlet fever and sore throat, or scarlatina; particularly as it appeared at Birmingham in the year 1778" Publ Cadell London

*1782 "An analysis of two mineral substance, vz. the Rowley rag-stone and the toad stone" ''Phil Trans 72: 327-36''

*1783 "Outlines of mineralogy" Publ Cadell, London (a translation of Bergmann's Latin original)

*1784 "Experiments and observations on the terra ponderosa" Phil trans 74: 293-311

*1785 "An account of the foxglove and some of its medical uses; with practical remarks on the dropsy, and some other diseases" Publ Swinney, Birmingham

*1787 "A botanical arrangement of British plants..." 2nd ed. Publ Swinney, London

*1788 Letter to

Edgbaston Hall Nature ReserveRevolutionary Players website'An account of the foxglove' book

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Withering, William 18th-century British botanists British phycologists British pteridologists Bryologists English mycologists 1741 births 1799 deaths Botanists with author abbreviations Fellows of the Royal Society Members of the Lunar Society of Birmingham Alumni of the University of Edinburgh People from Wellington, Shropshire 18th-century English medical doctors

botanist

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek wo ...

, geologist

A geologist is a scientist who studies the solid, liquid, and gaseous matter that constitutes Earth and other terrestrial planets, as well as the processes that shape them. Geologists usually study geology, earth science, or geophysics, althou ...

, chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''chēm(ía)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a scientist trained in the study of chemistry. Chemists study the composition of matter and its properties. Chemists carefully describe th ...

, physician

A physician (American English), medical practitioner (Commonwealth English), medical doctor, or simply doctor, is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through th ...

and first systematic investigator of the bioactivity of digitalis

''Digitalis'' ( or ) is a genus of about 20 species of herbaceous perennial plants, shrubs, and biennials, commonly called foxgloves.

''Digitalis'' is native to Europe, western Asia, and northwestern Africa. The flowers are tubular in shap ...

.

Withering was born in Wellington

Wellington ( mi, Te Whanganui-a-Tara or ) is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the second-largest city in New Zealand by ...

, Shropshire

Shropshire (; alternatively Salop; abbreviated in print only as Shrops; demonym Salopian ) is a landlocked historic county in the West Midlands region of England. It is bordered by Wales to the west and the English counties of Cheshire to ...

, the son of a surgeon. He trained as a physician

A physician (American English), medical practitioner (Commonwealth English), medical doctor, or simply doctor, is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through th ...

and studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh Medical School

The University of Edinburgh Medical School (also known as Edinburgh Medical School) is the medical school of the University of Edinburgh in Scotland and the United Kingdom and part of the University of Edinburgh College of Medicine and Veterinar ...

. He worked at Birmingham General Hospital

Birmingham General Hospital was a teaching hospital in Birmingham, England, founded in 1779 and closed in the mid-1990s.

History Summer Lane

In 1765, a committee for a proposed hospital, formed by John Ash and supported by Sir Lister ...

from 1779. The story is that he noticed a person with dropsy

Edema, also spelled oedema, and also known as fluid retention, dropsy, hydropsy and swelling, is the build-up of fluid in the body's tissue. Most commonly, the legs or arms are affected. Symptoms may include skin which feels tight, the area ma ...

(swelling from congestive heart failure

Heart failure (HF), also known as congestive heart failure (CHF), is a syndrome, a group of signs and symptoms caused by an impairment of the heart's blood pumping function. Symptoms typically include shortness of breath, excessive fatigue, ...

) improve remarkably after taking a traditional herbal remedy

Herbal medicine (also herbalism) is the study of pharmacognosy and the use of medicinal plants, which are a basis of traditional medicine. With worldwide research into pharmacology, some herbal medicines have been translated into modern remedies ...

; Withering became famous for recognising that the active ingredient in the mixture came from the foxglove

''Digitalis'' ( or ) is a genus of about 20 species of herbaceous perennial plants, shrubs, and biennials, commonly called foxgloves.

''Digitalis'' is native to Europe, western Asia, and northwestern Africa. The flowers are tubular in shap ...

plant. The active ingredient is now known as digoxin

Digoxin (better known as Digitalis), sold under the brand name Lanoxin among others, is a medication used to treat various heart conditions. Most frequently it is used for atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, and heart failure. Digoxin is o ...

, after the plant's scientific name. In 1785, Withering published ''An Account of the Foxglove and some of its Medical Uses'', which contained reports on clinical trial

Clinical trials are prospective biomedical or behavioral research studies on human participants designed to answer specific questions about biomedical or behavioral interventions, including new treatments (such as novel vaccines, drugs, diet ...

s and notes on digitalis's effects and toxicity

Toxicity is the degree to which a chemical substance or a particular mixture of substances can damage an organism. Toxicity can refer to the effect on a whole organism, such as an animal, bacterium, or plant, as well as the effect on a subs ...

.

Biography

Birmingham General Hospital

Birmingham General Hospital was a teaching hospital in Birmingham, England, founded in 1779 and closed in the mid-1990s.

History Summer Lane

In 1765, a committee for a proposed hospital, formed by John Ash and supported by Sir Lister ...

(at the suggestion of Erasmus Darwin, a physician and founder member of the Lunar Society

The Lunar Society of Birmingham was a British dinner club and informal learned society of prominent figures in the Midlands Enlightenment, including industrialists, natural philosophers and intellectuals, who met regularly between 1765 and 1813 ...

), but in 1783 he diagnosed himself as having pulmonary tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

and went twice to Portugal hoping the better winter climate would improve his health; it did not. On the way home from his second trip there, the ship he was in was chased by pirates. In 1785 he was elected a Fellow of the prestigious Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

and also published his ''Account of the Foxglove'' (see below). The following year he leased Edgbaston Hall, in Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands (county), West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1. ...

. He was one of the members of the Lunar Society

The Lunar Society of Birmingham was a British dinner club and informal learned society of prominent figures in the Midlands Enlightenment, including industrialists, natural philosophers and intellectuals, who met regularly between 1765 and 1813 ...

."William Withering (1741-1799): A Birmingham Lunatic" ''Proc R Coll Physicians Edinb 2001; 31:77-83.'' Accessed 28 June 2009/ref> During the Birmingham riots of 1791 (in which

Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley (; 24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, natural philosopher, separatist theologian, grammarian, multi-subject educator, and liberal political theorist. He published over 150 works, and conducted exp ...

's home was demolished) he prepared to flee from Edgbaston Hall, but his staff kept the rioters at bay until the military arrived. In 1799 he decided that he could not tolerate another winter in the cold and draughty Hall, so he bought "The Larches" in the nearby Sparkbrook

Sparkbrook is an inner-city area in south-east Birmingham, England. It is one of the four wards forming the Hall Green formal district within Birmingham City Council.

Etymology

The area receives its name from Spark Brook, a small stream that f ...

area; his wife did not feel up to the move and remained at Edgbaston Hall. After moving to The Larches on 28 September, he died on 6 October 1799.

Botany

In 1776, he published ''The botanical arrangement of all the vegetables naturally growing in Great Britain'', an early and influential British

In 1776, he published ''The botanical arrangement of all the vegetables naturally growing in Great Britain'', an early and influential British Flora

Flora is all the plant life present in a particular region or time, generally the naturally occurring (indigenous (ecology), indigenous) native plant, native plants. Sometimes bacteria and fungi are also referred to as flora, as in the terms '' ...

. It was the first in English based on the then new Linnaean taxonomy

Linnaean taxonomy can mean either of two related concepts:

# The particular form of biological classification (taxonomy) set up by Carl Linnaeus, as set forth in his ''Systema Naturae'' (1735) and subsequent works. In the taxonomy of Linnaeus t ...

— a classification of all living things — devised by the Swedish botanist and physician Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his Nobility#Ennoblement, ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalise ...

(1707–1778). At the time he was criticised for having produced a bowdlerised

Expurgation, also known as bowdlerization, is a form of censorship that involves purging anything deemed noxious or offensive from an artistic work or other type of writing or media.

The term ''bowdlerization'' is a pejorative term for the practi ...

version of Linnaeus, deliberately omitting any references to sexual reproduction, out of a desire to protect 'female modesty', notably by 'A Botanical Society, at Lichfield' - almost always incorrectly named as The Botanical Society of Lichfield or the Lichfield Botanical Society. Withering explained on the title page and his introduction that he avoided being explicit to allow his book to be used without any problems by a wider audience and in particular women."Dr. Withering...has translated parts of the ''Genera'' and ''Species Plantarum'' of LINNEUS; but has entirely omitted the sexual distinctions, which are essential to the philosophy of the system" However he found support for his position, and botany was considered a subject suitable for many women during the next century. A talented illustrator herself, his wife, Helena, sketched plants he collected.

Withering wrote two more editions of this work in 1787 and 1792, in collaboration with fellow Lunar Society member Jonathan Stokes, and after his death his son (also William) published four more. It continued being published under various authors until 1877. Withering senior also carried out pioneering work into the identification of fungi

A fungus ( : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as a kingdom, separately from ...

and invented a folding pocket microscope for use on botanical field trips. He also introduced to the general audience the screw down plant press and the vasculum. In 1787 he was elected a Fellow of the Linnaean Society in recognition of his contribution to botany. Subsequently, the plant ''Witheringia

''Witheringia'' is a genus of flowering plants in the family Solanaceae, with a neotropical distribution. It is closely related to ''Physalis

''Physalis'' (, , , , from φυσαλλίς ''phusallís'' "bladder") is a genus of approximately 7 ...

solanacea'' was named in his honour, and he became known on the continent of Europe as "The English Linnaeus". The William Withering Chair in Medicine at the University of Birmingham Medical School is named after him, as is the medical school's annual William Withering Lecture.

Discovery of digitalis

Allegedly, Withering first learned of the use of digitalis in treating "dropsy" ( œdema) from " Mother Hutton", an old woman who practised as a folk herbalist in Shropshire, who used the plant as part of apolyherbal formulation Polyherbal formulation (PHF) is the use of more than one herb in a medicinal preparation. The concept is found in Ayurvedic and other traditional medicinal systems where multiple herbs in a particular ratio may be used in the treatment of illness. ...

containing over 20 different ingredients to successfully treat this condition. Withering deduced that digitalis was the active ingredient in the formulation, and over the ensuing nine years he carefully tried out different preparations of various parts of the plant (collected in different seasons) documenting 156 cases where he had employed digitalis, and describing the effects and the best - and safest - way of using it. At least one of these cases was a patient for whom Erasmus Darwin had asked Withering for his second opinion. In January 1785 Darwin submitted a paper entitled "An Account of the Successful Use of Foxglove in Some Dropsies and in Pulmonary Consumption" to the College of Physicians in London;Medical Transactions, Volume 3, 1785, published by the College of Physicians, London. Transaction XVI, pp 255-286 it was presented by Darwin in March of that year. A postscriptMedical Transactions, Volume 3, 1785, published by the College of Physicians, London. Transaction XXVIII, p 448 at the end of the published volume of transactions containing Darwin's paper states that "Whilst the last pages of this volume were in the press, Dr Withering of Birmingham... published a numerous collection of cases in which foxglove has been given, and frequently with good success". After this, Darwin and Withering became increasingly estranged, and eventually an argument broke out apparently resulting from Robert Darwin having accused Withering of unprofessional behaviour by effectively poaching patients. This is a very early example of medical academic plagiarism. This was in reality orchestrated by Erasmus Darwin, a man whose anger and sarcasm when he felt slighted had in all likelihood contributed to the suicide of his own son and later to the estrangement of his son Robert.

In reality "Mother Hutton" was created in 1928 in an illustration by William Meade Prince as part of an advertising campaign by Parke-Davis who marketed digitalis preparations. There is no mention of a Mother Hutton in Withering's works or anyone else's and no mention of him meeting any old woman directly. In his account he states that he is merely asked to comment on a family recipe that was originally an old woman's receipt or recipe (that she had long kept secret) by a colleague. Since 1928, Mother Hutton's status has grown from being an image in an advertising poster to an acclaimed wise woman, herbalist, pharmacist and medical practitioner in Shropshire who was cheated out of her true recognition by Dr. Withering's unscrupulous methods. The story often written around this is also totally apocryphal. Withering was in fact informed of the Brasenose College, Oxford case by one of his medical colleagues Dr. Ash at Birmingham Hospital and the Dean was treated with digitalis root not leaves. The myth of Mother Hutton and how Withering chased her around Shropshire has been created by authors not going back to primary sources but instead copying and then embellishing the unreferenced work of others. See "Withering and The Foxglove; the making of a myth" by D.M. Krikler (British Heart Journal, 1985, 54: 256–257). In Withering's ''Account of the Foxglove'' printed in 1785 Withering mentions seven different occasions when foxglove was brought to his attention. Recognising that foxglove was the active ingredient in a family recipe (that was long kept secret by an old woman in Shropshire) would not have been difficult with his expert botanical knowledge. Withering had first published his ''Botanical Arrangement'' in 1776 and in it suggested foxglove deserved looking at in more detail. Erasmus Darwin tried to take the credit for foxglove and failed. Erasmus Darwin then attempted to try and discredit Withering behind the scenes with the unwitting help of his son Robert having earlier used the thesis of his dead son Charles to try and establish priority. Charles Darwin in fact had been friendly with Withering (as had Robert) and had talked in Edinburgh University about Withering's experiments with foxglove. Erasmus Darwin was probably jealous that Withering had become the most famous and sought-after doctor outside London and that Withering's English Botanical Arrangement became the standard reference source and far exceeded the botanical publications of Erasmus (all published semi-anonymously) in popularity. Withering's Botanical Arrangement, although now almost forgotten, became the standard reference for English Botany for almost the next 100 years.

In reality "Mother Hutton" was created in 1928 in an illustration by William Meade Prince as part of an advertising campaign by Parke-Davis who marketed digitalis preparations. There is no mention of a Mother Hutton in Withering's works or anyone else's and no mention of him meeting any old woman directly. In his account he states that he is merely asked to comment on a family recipe that was originally an old woman's receipt or recipe (that she had long kept secret) by a colleague. Since 1928, Mother Hutton's status has grown from being an image in an advertising poster to an acclaimed wise woman, herbalist, pharmacist and medical practitioner in Shropshire who was cheated out of her true recognition by Dr. Withering's unscrupulous methods. The story often written around this is also totally apocryphal. Withering was in fact informed of the Brasenose College, Oxford case by one of his medical colleagues Dr. Ash at Birmingham Hospital and the Dean was treated with digitalis root not leaves. The myth of Mother Hutton and how Withering chased her around Shropshire has been created by authors not going back to primary sources but instead copying and then embellishing the unreferenced work of others. See "Withering and The Foxglove; the making of a myth" by D.M. Krikler (British Heart Journal, 1985, 54: 256–257). In Withering's ''Account of the Foxglove'' printed in 1785 Withering mentions seven different occasions when foxglove was brought to his attention. Recognising that foxglove was the active ingredient in a family recipe (that was long kept secret by an old woman in Shropshire) would not have been difficult with his expert botanical knowledge. Withering had first published his ''Botanical Arrangement'' in 1776 and in it suggested foxglove deserved looking at in more detail. Erasmus Darwin tried to take the credit for foxglove and failed. Erasmus Darwin then attempted to try and discredit Withering behind the scenes with the unwitting help of his son Robert having earlier used the thesis of his dead son Charles to try and establish priority. Charles Darwin in fact had been friendly with Withering (as had Robert) and had talked in Edinburgh University about Withering's experiments with foxglove. Erasmus Darwin was probably jealous that Withering had become the most famous and sought-after doctor outside London and that Withering's English Botanical Arrangement became the standard reference source and far exceeded the botanical publications of Erasmus (all published semi-anonymously) in popularity. Withering's Botanical Arrangement, although now almost forgotten, became the standard reference for English Botany for almost the next 100 years.

Chemistry and geology

Withering was an enthusiastic chemist and geologist. He conducted a series of experiments on ''Terra Ponderosa'', a heavy ore from Cumberland, England. He deduced that it contained a hitherto undescribed element which he was unable to characterise. It was later shown to be

Withering was an enthusiastic chemist and geologist. He conducted a series of experiments on ''Terra Ponderosa'', a heavy ore from Cumberland, England. He deduced that it contained a hitherto undescribed element which he was unable to characterise. It was later shown to be barium carbonate

Barium carbonate is the inorganic compound with the formula BaCO3. Like most alkaline earth metal carbonates, it is a white salt that is poorly soluble in water. It occurs as the mineral known as witherite. In a commercial sense, it is one of ...

and in 1789 the German geologist Abraham Gottlob Werner named the mineral ''Witherite

Witherite is a barium carbonate mineral, Ba C O3, in the aragonite group. Witherite crystallizes in the orthorhombic system and virtually always is twinned. The mineral is colorless, milky-white, grey, pale-yellow, green, to pale-brown. The spec ...

'' in his honour."William Withering (1741-1799): a biographical sketch of a Birmingham Lunatic." M R Lee, ''James Lind Library'', accessed 25 September 2006/ref> The

Matthew Boulton

Matthew Boulton (; 3 September 172817 August 1809) was an English manufacturer and business partner of Scottish engineer James Watt. In the final quarter of the 18th century, the partnership installed hundreds of Boulton & Watt steam engin ...

mineral collection of Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery

Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery (BM&AG) is a museum and art gallery in Birmingham, England. It has a collection of international importance covering fine art, ceramics, metalwork, jewellery, natural history, archaeology, ethnography, local ...

may contain one of the earliest known specimens of witherite. A label in Boulton's handwriting records; "No.2 Terra Ponderosa Aerata, given me by Dr. Withering"

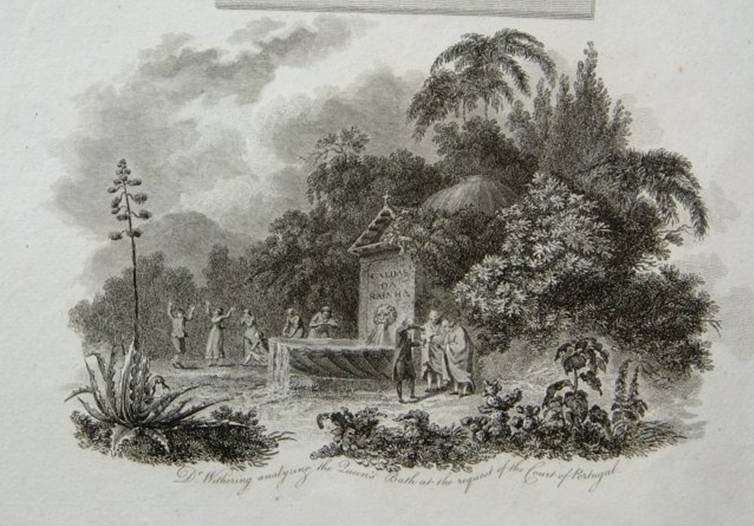

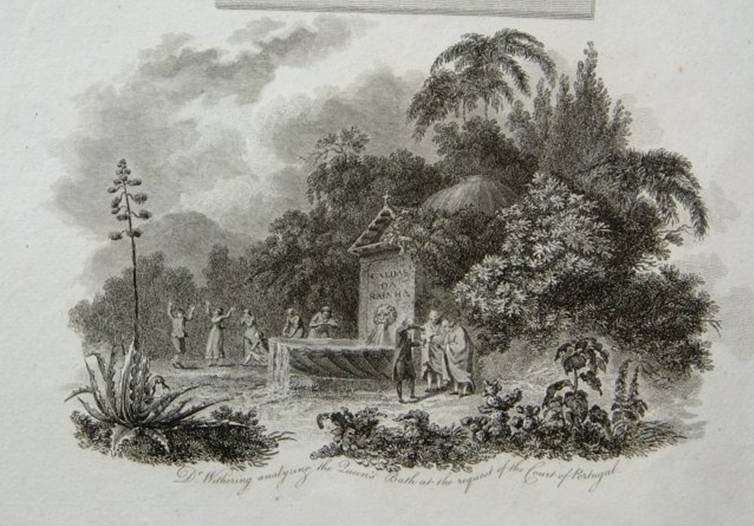

Withering also undertook analyses of the mineral content of a number of spa waters in England and abroad, notably at the medicinal spa at Caldas da Rainha

Caldas da Rainha () is a medium-sized Portuguese city in the Oeste region, in the historical province of Estremadura, and in the district of Leiria. The city serves as the seat of the larger municipality of the same name and of the Comunidad ...

in Portugal. This latter undertaking occurred during the winter of 1793–4, and he was subsequently elected to the Fellowship of the Royal Academy of Sciences of Portugal.

Memorials

He was buried on 10 October 1799 in Edgbaston Old Church next to Edgbaston Hall, Birmingham, although the exact site of his grave is unknown. The memorial stone, now moved inside the church, has foxgloves and ''Witheringia solanaceae'' carved upon it to commemorate his discovery and his wider contribution to botany. He is also remembered by one of the Lunar Society Moonstones in Birmingham and by a blue plaque at Edgbaston Hall.Birmingham University

, mottoeng = Through efforts to heights

, established = 1825 – Birmingham School of Medicine and Surgery1836 – Birmingham Royal School of Medicine and Surgery1843 – Queen's College1875 – Mason Science College1898 – Mason Univers ...

School of Medicine established a Chair of Medicine post in his honour, named after him.

In July 2011 a J D Wetherspoon

J D Wetherspoon plc (branded variously as Wetherspoon or Wetherspoons, and colloquially known as Spoons) is a pub company operating in the United Kingdom and Ireland. The company was founded in 1979 by Tim Martin and is based in Watford. It o ...

public house

A pub (short for public house) is a kind of drinking establishment which is licensed to serve alcoholic drinks for consumption on the premises. The term ''public house'' first appeared in the United Kingdom in late 17th century, and wa ...

opened in Withering's birthplace, Wellington, and has been named after him.July 2011

Publications

Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley (; 24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, natural philosopher, separatist theologian, grammarian, multi-subject educator, and liberal political theorist. He published over 150 works, and conducted exp ...

on the principle of acidity, the decomposition of water. Phil Trans 78: 319-330

*1790 "An account of some extraordinary effects of lightning" ''Phil Trans 80: 293-5''

*1793 "An account of the scarlet fever and sore throat..." 2nd ed Publ Robinson, London

*1793 "A chemical analysis of waters at Caldas" extract from ''Actas da Academica real das Sciencias''

*1794 "A new method for preserving fungi, ascertained by chymical experiments" ''Trans Linnean Soc 2: 263-6''

*1795 "Analyse chimica da aqua das Caldas da Rainha" Lisbon (a chemical analysis of the water of Caldas da Rainha)

*1796 "Observations on the pneumatic medicine" Ann Med 1: 392-3

*1796 "An arrangement of British plants..." 3rd ed. Publ Swinney, London

*1799 "An account of a convenient method of inhaling the vapour of volatile substances" ''Ann Med 3: 47-51''

Notes

References

Further reading

* * William Withering Junior (1822). ''Miscellaneous Tracts''. Two volumes: a memoir by Withering's son, and a collection of many of his writings * Louis H Roddis (1936). ''William Withering - The Introduction of Digitalis into Clinical Practice''. A brief biography * TW Peck and KD Wilkinson (1950). ''William Withering of Birmingham''. A detailed biography * * J K Aronson (1985). ''An Account of the Foxglove and its Medical Uses 1785-1985''. An annotated version of the Withering's work, with a modern analysis of the cases described * Jenny Uglow (2002). ''The Lunar Men''. . An account of the members of the Lunar Society, their endeavours, and relationships * *External links

Edgbaston Hall Nature Reserve

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Withering, William 18th-century British botanists British phycologists British pteridologists Bryologists English mycologists 1741 births 1799 deaths Botanists with author abbreviations Fellows of the Royal Society Members of the Lunar Society of Birmingham Alumni of the University of Edinburgh People from Wellington, Shropshire 18th-century English medical doctors