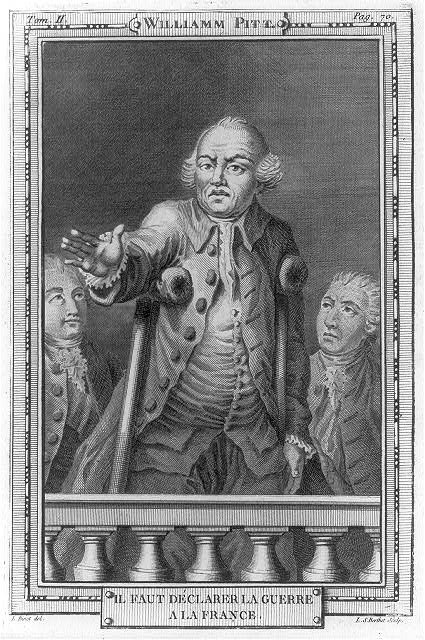

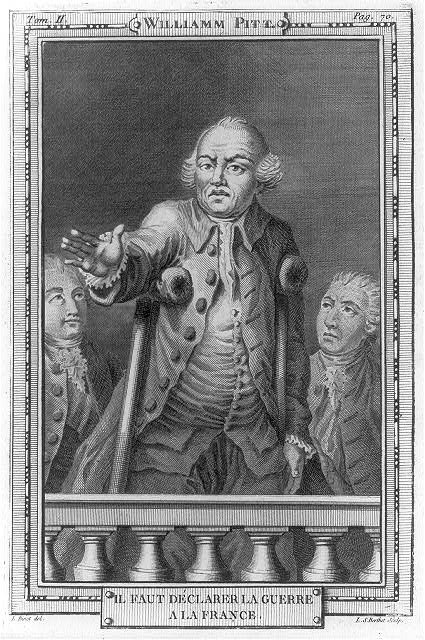

William Pitt the Elder on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham, (15 November 170811 May 1778) was a British statesman of the Whig group who served as

William's father was

William's father was

On Pitt's return home it was necessary for him, as the younger son, to choose a profession and he opted for a career in the army. He obtained a

On Pitt's return home it was necessary for him, as the younger son, to choose a profession and he opted for a career in the army. He obtained a

Walpole and Newcastle were now giving the war in Europe a much higher priority than the colonial conflict with Spain in the Americas.

Walpole and Newcastle were now giving the war in Europe a much higher priority than the colonial conflict with Spain in the Americas.

Despite his disappointment there was no immediate open breach. Pitt continued at his post; and at the general election which took place during the year he even accepted a nomination for the Duke's

Despite his disappointment there was no immediate open breach. Pitt continued at his post; and at the general election which took place during the year he even accepted a nomination for the Duke's  Eager to prevent the war spreading to Europe, Newcastle now tried to conclude a series of treaties that would secure Britain allies through the payment of subsidies, which he hoped would discourage France from attacking Britain. Similar subsidies had been an issue of past disagreement, and they were widely attacked by Patriot Whigs and Tories. As the government came under increasing attack, Newcastle replaced Robinson with Fox who it was acknowledged carried more political weight and again slighted Pitt.

Finally in November 1755, Pitt was dismissed from office as paymaster, having spoken during a debate at great length against the new system of continental subsidies proposed by the government of which he was still a member. Fox retained his own place, and though the two men continued to be of the same party, and afterwards served again in the same government, there was henceforward a rivalry between them, which makes the celebrated opposition of their sons,

Eager to prevent the war spreading to Europe, Newcastle now tried to conclude a series of treaties that would secure Britain allies through the payment of subsidies, which he hoped would discourage France from attacking Britain. Similar subsidies had been an issue of past disagreement, and they were widely attacked by Patriot Whigs and Tories. As the government came under increasing attack, Newcastle replaced Robinson with Fox who it was acknowledged carried more political weight and again slighted Pitt.

Finally in November 1755, Pitt was dismissed from office as paymaster, having spoken during a debate at great length against the new system of continental subsidies proposed by the government of which he was still a member. Fox retained his own place, and though the two men continued to be of the same party, and afterwards served again in the same government, there was henceforward a rivalry between them, which makes the celebrated opposition of their sons,

In December 1756, Pitt, who now sat for

In December 1756, Pitt, who now sat for

A coalition with Newcastle was formed in June 1757, and held power until October 1761. It brought together several various factions and was built around the partnership between Pitt and Newcastle, which a few months earlier had seemed impossible. The two men used

A coalition with Newcastle was formed in June 1757, and held power until October 1761. It brought together several various factions and was built around the partnership between Pitt and Newcastle, which a few months earlier had seemed impossible. The two men used

In France a new leader, the Étienne François, duc de Choiseul, Duc de Choiseul, had recently come to power and 1759 offered a duel between their rival strategies. Pitt intended to continue with his plan of tying down French forces in Germany while continuing the assault on France's colonies. Choiseul hoped to repel the attacks in the colonies while seeking total victory in Europe.

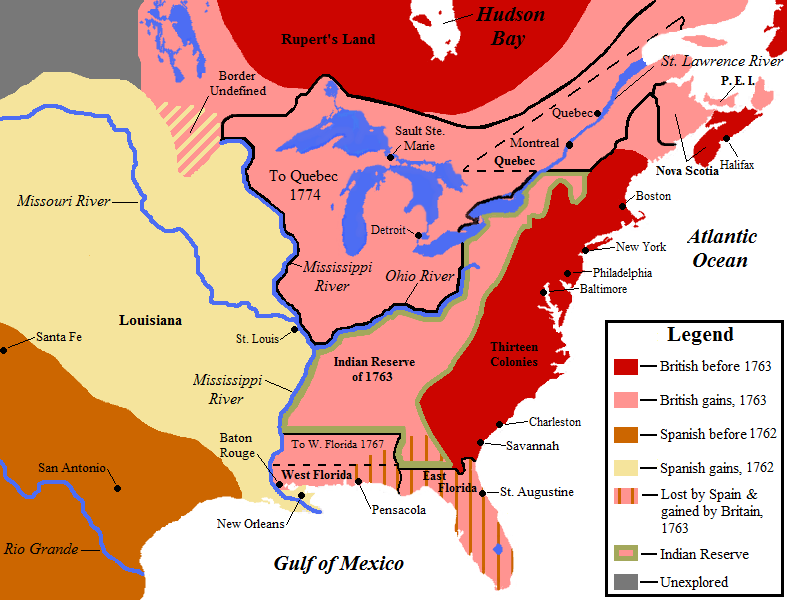

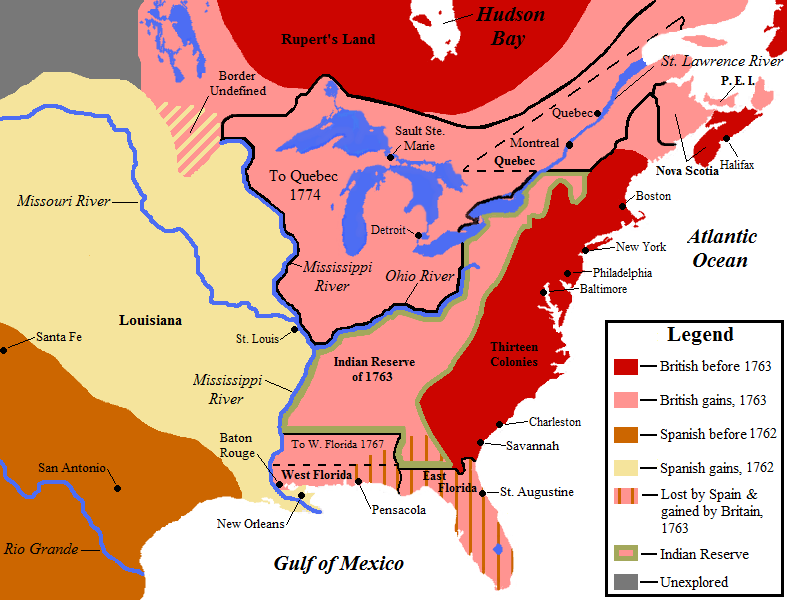

Pitt's war around the world was largely successful. While a British Invasion of Martinique (1759), invasion of Martinique failed, they Invasion of Guadeloupe (1759), captured Guadeloupe shortly afterwards. In India, a French Siege of Madras, attempt to capture Madras was repulsed. In North America, British troops closed in on France's Canadian heartland. A British force under James Wolfe moved up the Saint Lawrence River, Saint Lawrence with the aim of capturing Quebec. After initially Battle of Beauport, failing to penetrate the French defences at the Montmorency Falls, Wolfe later led his men Battle of the Plains of Abraham, to a victory to the west of the city allowing the British forces to capture Quebec.

Choiseul had pinned much of his hopes on Planned French Invasion of Britain (1759), a French invasion of Britain, which he hoped would knock Britain out of the war and make it surrender the colonies it had taken from France. Pitt had stripped the home islands of troops to send on his expeditions, leaving Britain guarded by poorly trained militia and giving an opportunity for the French if they could land in enough force. The French did build a large invasion force. However the French naval defeats at Battle of Lagos, Lagos and Battle of Quiberon Bay, Quiberon Bay forced Choiseul to abandon the invasion plans. France's other great hope, that their armies could make a breakthrough in Germany and invade Hanover, was thwarted at the Battle of Minden. Britain ended the year victorious in every theatre of operations in which it was engaged, with Pitt receiving the credit for this.

In France a new leader, the Étienne François, duc de Choiseul, Duc de Choiseul, had recently come to power and 1759 offered a duel between their rival strategies. Pitt intended to continue with his plan of tying down French forces in Germany while continuing the assault on France's colonies. Choiseul hoped to repel the attacks in the colonies while seeking total victory in Europe.

Pitt's war around the world was largely successful. While a British Invasion of Martinique (1759), invasion of Martinique failed, they Invasion of Guadeloupe (1759), captured Guadeloupe shortly afterwards. In India, a French Siege of Madras, attempt to capture Madras was repulsed. In North America, British troops closed in on France's Canadian heartland. A British force under James Wolfe moved up the Saint Lawrence River, Saint Lawrence with the aim of capturing Quebec. After initially Battle of Beauport, failing to penetrate the French defences at the Montmorency Falls, Wolfe later led his men Battle of the Plains of Abraham, to a victory to the west of the city allowing the British forces to capture Quebec.

Choiseul had pinned much of his hopes on Planned French Invasion of Britain (1759), a French invasion of Britain, which he hoped would knock Britain out of the war and make it surrender the colonies it had taken from France. Pitt had stripped the home islands of troops to send on his expeditions, leaving Britain guarded by poorly trained militia and giving an opportunity for the French if they could land in enough force. The French did build a large invasion force. However the French naval defeats at Battle of Lagos, Lagos and Battle of Quiberon Bay, Quiberon Bay forced Choiseul to abandon the invasion plans. France's other great hope, that their armies could make a breakthrough in Germany and invade Hanover, was thwarted at the Battle of Minden. Britain ended the year victorious in every theatre of operations in which it was engaged, with Pitt receiving the credit for this.

To the preliminaries of the Treaty of Paris (1763), peace concluded in February 1763 he offered an indignant resistance, considering the terms quite inadequate to the successes that had been gained by the country. When the treaty was discussed in parliament in December of the previous year, though suffering from a severe attack of gout, he was carried down to the House, and in a speech of three hours' duration, interrupted more than once by paroxysms of pain, he strongly protested against its various conditions. These conditions included the return of the sugar islands (but Britain retained Dominica); trading stations in West Africa (won by Boscawen); Pondicherry (city), Pondicherry (French India, France's Indian colony); and fishing rights in Newfoundland. Pitt's opposition arose through two heads: France had been given the means to become once more formidable at sea, whilst Frederick the Great, Frederick of Prussia had been betrayed.

Pitt believed that the task had been left half-finished and called for a final year of war which would crush French power for good. Pitt had long-held plans for further conquests which had been uncompleted. Newcastle, by contrast, sought peace but only if the war in Germany could be brought to an honourable and satisfactory conclusion (rather than Britain suddenly bailing out of it as Bute proposed). However the combined opposition of Newcastle and Pitt was not enough to prevent the Treaty passing comfortably in both Houses of Parliament.

However, there were strong reasons for concluding the peace: the National Debt had increased from £74.5m. in 1755 to £133.25m. in 1763, the year of the Treaty of Paris (1763), peace. The requirement to pay down this debt, and the lack of French threat in Canada, were major movers in the subsequent American War of Independence.

The physical cause which rendered this effort so painful probably accounts for the infrequency of his appearances in parliament, as well as for much that is otherwise inexplicable in his subsequent conduct. In 1763 he spoke against the unpopular Cider Bill of 1763, tax on cider, imposed by his brother-in-law, George Grenville, and his opposition, though unsuccessful in the House, helped to keep alive his popularity with the country, which cordially hated the excise and all connected with it. When next year the question of general warrants was raised in connexion with the case of John Wilkes, Pitt vigorously maintained their illegality, thus defending at once the privileges of Parliament and the freedom of the press.

During 1765 he seems to have been totally :wikt:incapacitation, incapacitated for public business. In the following year he supported with great power the proposal of the Charles Watson-Wentworth, 2nd Marquess of Rockingham, Rockingham administration for the repeal of the Stamp Act 1765, Stamp Act, arguing that it was unconstitutional to impose taxes upon the colonies. He thus endorsed the contention of the colonists on the ground of principle, while the majority of those who acted with him contented themselves with resisting the disastrous taxation scheme on the ground of expediency.

The Repeal (1766) of the Stamp Act, indeed, was only passed ''pari passu'' with Declaratory Act, another censuring the American Deliberative assembly, assemblies, and declaring the authority of the British parliament over the colonies "in all cases whatsoever". Thus the House of Commons repudiated in the most formal manner the principle Pitt laid down. His language in approval of the resistance of the colonists was unusually bold, and perhaps no one but himself could have employed it with impunity at a time when the freedom of debate was only imperfectly conceded.

Pitt had not been long out of office when he was solicited to return to it, and the solicitations were more than once renewed. Unsuccessful overtures were made to him in 1763, and twice in 1765, in May and June—the negotiator in May being the king's uncle, the Prince William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, Duke of Cumberland, who went down in person to Hayes, Bromley, Hayes, Pitt's seat in Kent. It is known that he had the opportunity of joining the Marquess of Rockingham's short-lived administration at any time on his own terms, and his conduct in declining an arrangement with that minister has been more generally condemned than any other step in his public life.

To the preliminaries of the Treaty of Paris (1763), peace concluded in February 1763 he offered an indignant resistance, considering the terms quite inadequate to the successes that had been gained by the country. When the treaty was discussed in parliament in December of the previous year, though suffering from a severe attack of gout, he was carried down to the House, and in a speech of three hours' duration, interrupted more than once by paroxysms of pain, he strongly protested against its various conditions. These conditions included the return of the sugar islands (but Britain retained Dominica); trading stations in West Africa (won by Boscawen); Pondicherry (city), Pondicherry (French India, France's Indian colony); and fishing rights in Newfoundland. Pitt's opposition arose through two heads: France had been given the means to become once more formidable at sea, whilst Frederick the Great, Frederick of Prussia had been betrayed.

Pitt believed that the task had been left half-finished and called for a final year of war which would crush French power for good. Pitt had long-held plans for further conquests which had been uncompleted. Newcastle, by contrast, sought peace but only if the war in Germany could be brought to an honourable and satisfactory conclusion (rather than Britain suddenly bailing out of it as Bute proposed). However the combined opposition of Newcastle and Pitt was not enough to prevent the Treaty passing comfortably in both Houses of Parliament.

However, there were strong reasons for concluding the peace: the National Debt had increased from £74.5m. in 1755 to £133.25m. in 1763, the year of the Treaty of Paris (1763), peace. The requirement to pay down this debt, and the lack of French threat in Canada, were major movers in the subsequent American War of Independence.

The physical cause which rendered this effort so painful probably accounts for the infrequency of his appearances in parliament, as well as for much that is otherwise inexplicable in his subsequent conduct. In 1763 he spoke against the unpopular Cider Bill of 1763, tax on cider, imposed by his brother-in-law, George Grenville, and his opposition, though unsuccessful in the House, helped to keep alive his popularity with the country, which cordially hated the excise and all connected with it. When next year the question of general warrants was raised in connexion with the case of John Wilkes, Pitt vigorously maintained their illegality, thus defending at once the privileges of Parliament and the freedom of the press.

During 1765 he seems to have been totally :wikt:incapacitation, incapacitated for public business. In the following year he supported with great power the proposal of the Charles Watson-Wentworth, 2nd Marquess of Rockingham, Rockingham administration for the repeal of the Stamp Act 1765, Stamp Act, arguing that it was unconstitutional to impose taxes upon the colonies. He thus endorsed the contention of the colonists on the ground of principle, while the majority of those who acted with him contented themselves with resisting the disastrous taxation scheme on the ground of expediency.

The Repeal (1766) of the Stamp Act, indeed, was only passed ''pari passu'' with Declaratory Act, another censuring the American Deliberative assembly, assemblies, and declaring the authority of the British parliament over the colonies "in all cases whatsoever". Thus the House of Commons repudiated in the most formal manner the principle Pitt laid down. His language in approval of the resistance of the colonists was unusually bold, and perhaps no one but himself could have employed it with impunity at a time when the freedom of debate was only imperfectly conceded.

Pitt had not been long out of office when he was solicited to return to it, and the solicitations were more than once renewed. Unsuccessful overtures were made to him in 1763, and twice in 1765, in May and June—the negotiator in May being the king's uncle, the Prince William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, Duke of Cumberland, who went down in person to Hayes, Bromley, Hayes, Pitt's seat in Kent. It is known that he had the opportunity of joining the Marquess of Rockingham's short-lived administration at any time on his own terms, and his conduct in declining an arrangement with that minister has been more generally condemned than any other step in his public life.

Pitt's particular genius was to finance an army on the continent to drain French men and resources so that Britain might concentrate on what he held to be the vital spheres: Canada and the West Indies; whilst Clive successfully defeated Siraj ud-Daulah, (the last independent Nawab of Bengal) at Plassey (1757), securing India. The Continental campaign was carried on by Prince William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, Cumberland, defeated at Battle of Hastenbeck, Hastenbeck and forced to surrender at

Pitt's particular genius was to finance an army on the continent to drain French men and resources so that Britain might concentrate on what he held to be the vital spheres: Canada and the West Indies; whilst Clive successfully defeated Siraj ud-Daulah, (the last independent Nawab of Bengal) at Plassey (1757), securing India. The Continental campaign was carried on by Prince William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, Cumberland, defeated at Battle of Hastenbeck, Hastenbeck and forced to surrender at

George II died on 25 October 1760, and was succeeded by his grandson, George III of the United Kingdom, George III. The new king was inclined to view politics in personal terms and taught to believe that "Pitt had the blackest of hearts". The new king had counsellors of his own, led by John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute, Lord Bute. Bute soon joined the cabinet as a secretary of state, Northern Secretary and Pitt and he were quickly in dispute over a number of issues.

In 1761 Pitt had received information from his agents about a secret Pacte de Famille, Bourbon Family Compact by which the House of Bourbon, Bourbons of France and Spain bound themselves in an offensive alliance against Britain. Spain was concerned that Britain's victories over France had left them too powerful, and were a threat in the long term to Spain's Spanish Empire, own empire. Equally they may have believed that the British had become overstretched by fighting a global war and decided to try to seize British possessions such as

George II died on 25 October 1760, and was succeeded by his grandson, George III of the United Kingdom, George III. The new king was inclined to view politics in personal terms and taught to believe that "Pitt had the blackest of hearts". The new king had counsellors of his own, led by John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute, Lord Bute. Bute soon joined the cabinet as a secretary of state, Northern Secretary and Pitt and he were quickly in dispute over a number of issues.

In 1761 Pitt had received information from his agents about a secret Pacte de Famille, Bourbon Family Compact by which the House of Bourbon, Bourbons of France and Spain bound themselves in an offensive alliance against Britain. Spain was concerned that Britain's victories over France had left them too powerful, and were a threat in the long term to Spain's Spanish Empire, own empire. Equally they may have believed that the British had become overstretched by fighting a global war and decided to try to seize British possessions such as

Soon after his resignation a renewed attack of gout freed Chatham from the mental disease under which he had so long suffered. He had been nearly two years and a half in seclusion when, in July 1769, he again appeared in public at a royal levee. It was not, however, until 1770 that he resumed his seat in the House of Lords.

Soon after his resignation a renewed attack of gout freed Chatham from the mental disease under which he had so long suffered. He had been nearly two years and a half in seclusion when, in July 1769, he again appeared in public at a royal levee. It was not, however, until 1770 that he resumed his seat in the House of Lords.

Pitt had now almost no personal following, mainly owing to the grave mistake he had made in not forming an alliance with the Rockingham party, but his eloquence was as powerful as ever, and all its power was directed against the government policy in the contest with America, which had become the question of all-absorbing interest. His last appearance in the House of Lords was on 7 April 1778, on the occasion of the Charles Lennox, 3rd Duke of Richmond, Duke of Richmond's motion for an address praying the king to conclude peace with America on any terms.

In view of the hostile demonstrations of France the various parties had come generally to see the necessity of such a measure but Chatham could not brook the thought of a step which implied submission to the "natural enemy" whom it had been the main object of his life to humble, and he declaimed for a considerable time, though with diminished vigour, against the motion. After the Duke of Richmond had replied, he rose again excitedly as if to speak, pressed his hand upon his breast, and fell down in a fit. His last words before he collapsed were: "My Lords, any state is better than despair; if we must fall, let us fall like men." James Harris, 1st Earl of Malmesbury, James Harris MP, however, recorded that Robert Nugent, 1st Earl Nugent, Lord Nugent had told him that Chatham's last words in the Lords were: "If the Americans defend independence, they shall find me in their way" and that his very last words (spoken to John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham, his soldier son John) were: "Leave your dying father, and go to the defence of your country".

He was moved to his home at Hayes, where his middle son William Pitt the Younger, William read to him Homer's passage about the death of Hector. Chatham died on 11 May 1778, aged 69. Although he was initially buried at Hayes, with graceful unanimity all parties combined to show their sense of the national loss and the Commons presented an address to the king praying that the deceased statesman might be buried with the honours of a public funeral. A sum was voted for a public monument which was erected over a new grave in Westminster Abbey. The monument, by the sculptor John Bacon (sculptor, born 1740), John Bacon, has a figure of Pitt above statues of Britannia and Neptune (mythology), Neptune with figures representing Prudence, Fortitude, the Earth and also a sea creature.

In the Guildhall, London, Guildhall Edmund Burke's inscription summed up what he had meant to the city: he was "the minister by whom commerce was united with and made to flourish by war". Soon after the funeral a bill was passed bestowing a pension of £4,000 a year on his successors in the earldom. He had a family of three sons and two daughters, of whom the second son, William Pitt the Younger, William, was destined to add fresh lustre to a name that many regarded as one of the greatest in the history of England.

Pitt had now almost no personal following, mainly owing to the grave mistake he had made in not forming an alliance with the Rockingham party, but his eloquence was as powerful as ever, and all its power was directed against the government policy in the contest with America, which had become the question of all-absorbing interest. His last appearance in the House of Lords was on 7 April 1778, on the occasion of the Charles Lennox, 3rd Duke of Richmond, Duke of Richmond's motion for an address praying the king to conclude peace with America on any terms.

In view of the hostile demonstrations of France the various parties had come generally to see the necessity of such a measure but Chatham could not brook the thought of a step which implied submission to the "natural enemy" whom it had been the main object of his life to humble, and he declaimed for a considerable time, though with diminished vigour, against the motion. After the Duke of Richmond had replied, he rose again excitedly as if to speak, pressed his hand upon his breast, and fell down in a fit. His last words before he collapsed were: "My Lords, any state is better than despair; if we must fall, let us fall like men." James Harris, 1st Earl of Malmesbury, James Harris MP, however, recorded that Robert Nugent, 1st Earl Nugent, Lord Nugent had told him that Chatham's last words in the Lords were: "If the Americans defend independence, they shall find me in their way" and that his very last words (spoken to John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham, his soldier son John) were: "Leave your dying father, and go to the defence of your country".

He was moved to his home at Hayes, where his middle son William Pitt the Younger, William read to him Homer's passage about the death of Hector. Chatham died on 11 May 1778, aged 69. Although he was initially buried at Hayes, with graceful unanimity all parties combined to show their sense of the national loss and the Commons presented an address to the king praying that the deceased statesman might be buried with the honours of a public funeral. A sum was voted for a public monument which was erected over a new grave in Westminster Abbey. The monument, by the sculptor John Bacon (sculptor, born 1740), John Bacon, has a figure of Pitt above statues of Britannia and Neptune (mythology), Neptune with figures representing Prudence, Fortitude, the Earth and also a sea creature.

In the Guildhall, London, Guildhall Edmund Burke's inscription summed up what he had meant to the city: he was "the minister by whom commerce was united with and made to flourish by war". Soon after the funeral a bill was passed bestowing a pension of £4,000 a year on his successors in the earldom. He had a family of three sons and two daughters, of whom the second son, William Pitt the Younger, William, was destined to add fresh lustre to a name that many regarded as one of the greatest in the history of England.

Horace Walpole, not an uncritical admirer, wrote of Pitt:

Horace Walpole, not an uncritical admirer, wrote of Pitt:

/ref> The American city of

"Lines To A Gentleman"

which Burns composed in response to being sent a newspaper, which the gentlemen sender offered to continue providing free of charge. The poet's satirical summary of events makes clear that he has no interest in the reports contained in the newspaper. The poem's section on events in Parliament, which refers to Pitt as 'Chatham Will', is as follows:

online

older classic recommended by Jeremy Black (1992) * Sherrard, O. A. ''Lord Chatham: A War Minister in the Making; Pitt and the Seven Years War; and America'' (3 vols, The Bodley Head, 1952–58) * * Williams, Basil. ''The Life of William Pitt, Earl of Chatham'' (2 vols, 1915

vol 1 onlinevol 2 online free

online

587pp; useful old classic, strong on politics 1714–1815. * Robertson, Charles. Grant ''Chatham and the British empire'' (1948

online

* Rodger N. A. M. ''Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain, 1649–1815''. Penguin Books, 2006. * * Charles Chenevix Trench, Trench, Chenevix Charles. ''George II''. Allen Lane, 1973 * Turner, Michael J. ''Pitt the Younger: A Life''. Hambledon & London, 2003. * Williams, Basil. '' "The Whig Supremacy, 1714–1760'' (2nd ed. 1962) pp 354–77, on his roles 1756–63. * Wolfe, Eugene L. ''Dangerous Seats: Parliamentary Violence in the United Kingdom'' Amberley, 2019. * Woodfine, Philip. ''Britannia's Glories: The Walpole Ministry and the 1739 War with Spain''. Boydell Press, 1998.

More about The Earl of Chatham, William Pitt 'The Elder'

on the Downing Street website.

William Pitt's Defense of the American Colonies

Bronze Bust of William Pitt

by William Reid Dick (1922) to Pittsburgh Mayor William A. Magee, by Charles Wakefield, 1st Viscount Wakefield * hdl:10079/fa/beinecke.pitt, William Pitt Collection. General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. {{DEFAULTSORT:Chatham, William Pitt, 1st Earl Of 1708 births 1778 deaths People from Westminster People educated at Eton College, Pitt, William Alumni of Trinity College, Oxford Members of the Parliament of Great Britain for English constituencies, Pitt, William British MPs 1734–1741 British MPs 1741–1747 British MPs 1747–1754 British MPs 1754–1761 British MPs 1761–1768 Prime Ministers of Great Britain Secretaries of State for the Southern Department Paymasters of the Forces Lords Privy Seal Whig (British political party) MPs for English constituencies Members of the Privy Council of Great Britain British people of the French and Indian War Earls in the Peerage of Great Britain Peers of Great Britain created by George III Burials at Westminster Abbey 18th-century heads of government Leaders of the House of Commons of Great Britain Fellows of the Royal Society Pitt family, William Parents of prime ministers of the United Kingdom 1st King's Dragoon Guards officers British people of the Seven Years' War MPs for rotten boroughs Members of the Parliament of Great Britain for Okehampton

Prime Minister of Great Britain

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As modern pri ...

from 1766 to 1768. Historians call him Chatham or William Pitt the Elder to distinguish him from his son William Pitt the Younger

William Pitt the Younger (28 May 175923 January 1806) was a British statesman, the youngest and last prime minister of Great Britain (before the Acts of Union 1800) and then first prime minister of the United Kingdom (of Great Britain and Ire ...

, who was also a prime minister. Pitt was also known as the Great Commoner, because of his long-standing refusal to accept a title until 1766.

Pitt was a member of the British cabinet and its informal leader from 1756 to 1761 (with a brief interlude in 1757), during the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

(including the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the ...

in the American colonies). He again led the ministry, holding the official title of Lord Privy Seal

The Lord Privy Seal (or, more formally, the Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal) is the fifth of the Great Officers of State (United Kingdom), Great Officers of State in the United Kingdom, ranking beneath the Lord President of the Council and abov ...

, between 1766 and 1768. Much of his power came from his brilliant oratory. He was out of power for most of his career and became well known for his attacks on the government, such as those on Walpole's corruption in the 1730s, Hanoverian subsidies in the 1740s, peace with France in the 1760s, and the uncompromising policy towards the American colonies in the 1770s.

Pitt is best known as the wartime political leader of Britain in the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

, especially for his single-minded devotion to victory over France, a victory which ultimately solidified Britain's dominance over world affairs. He is also known for his popular appeal, his opposition to corruption in government, his support for the American position in the run-up to the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, his advocacy of British greatness, expansionism and empire, and his antagonism towards Britain's chief enemies and rivals for colonial power, Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

. Marie Peters argues his statesmanship was based on a clear, consistent, and distinct appreciation of the value of the Empire.

The British parliamentary historian P. D. G. Thomas

Peter David Garner Thomas ( 1 May 1930 - 7 July 2020) was a Welsh historian specialising in 18th-century British and American politics.

Thomas was born in Bangor, Wales, and educated at the University College of North Wales and University College ...

argued that Pitt's power was based not on his family connections but on the extraordinary parliamentary skills by which he dominated the House of Commons. He displayed a commanding manner, brilliant rhetoric, and sharp debating skills that cleverly utilised broad literary and historical knowledge. Scholars rank him highly among all British prime ministers.

Early life

Family

Pitt was the grandson ofThomas Pitt

Thomas Pitt (5 July 1653 – 28 April 1726) of Blandford St Mary in Dorset, later of Stratford in Wiltshire and of Boconnoc in Cornwall, known during life commonly as ''Governor Pitt'', as ''Captain Pitt'', or posthumously, as ''"Diamond" ...

(1653–1726), the governor of Madras

Chennai (, ), formerly known as Madras ( the official name until 1996), is the capital city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost Indian state. The largest city of the state in area and population, Chennai is located on the Coromandel Coast of th ...

, known as "Diamond" Pitt for having discovered a diamond of extraordinary size and sold it to the Duke of Orléans

Duke of Orléans (french: Duc d'Orléans) was a French royal title usually granted by the King of France to one of his close relatives (usually a younger brother or son), or otherwise inherited through the male line. First created in 1344 by King ...

for around £135,000. This transaction, as well as other trading deals in India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, established the Pitt family fortune. After returning home the Governor was able to raise his family to a position of wealth and political influence: in 1691 he purchased the property of Boconnoc

Boconnoc ( kw, Boskennek) is a civil parishes in England, civil parish in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom, approximately four miles east of the town of Lostwithiel. According to the UK census 2011, 2011 census the parish had a population of 9 ...

in Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a historic county and ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people. Cornwall is bordered to the north and west by the Atlantic ...

, which gave him control of a seat in Parliament. He made further land purchases and became one of the dominant political figures in the West Country

The West Country (occasionally Westcountry) is a loosely defined area of South West England, usually taken to include all, some, or parts of the counties of Cornwall, Devon, Dorset, Somerset, Bristol, and, less commonly, Wiltshire, Gloucesters ...

, controlling seats such as the rotten borough

A rotten or pocket borough, also known as a nomination borough or proprietorial borough, was a parliamentary borough or constituency in England, Great Britain, or the United Kingdom before the Reform Act 1832, which had a very small electorat ...

of Old Sarum

Old Sarum, in Wiltshire, South West England, is the now ruined and deserted site of the earliest settlement of Salisbury. Situated on a hill about north of modern Salisbury near the A345 road, the settlement appears in some of the earliest re ...

.

William's father was

William's father was Robert Pitt

Robert Pitt (1680 – 21 May 1727) was a British politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1705 to 1727. He was the father and grandfather of two prime ministers, William Pitt the elder and William Pitt the younger.

Early life

Pitt was th ...

(1680–1727), the eldest son of Governor Pitt, who served as a Tory

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. Th ...

Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

from 1705 to 1727. His mother was Harriet Villiers, the daughter of Edward Villiers-FitzGerald and the Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

heiress Katherine FitzGerald. Both William's paternal uncles Thomas

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the A ...

and John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

were MPs, while his aunt Lucy

Lucy is an English feminine given name derived from the Latin masculine given name Lucius with the meaning ''as of light'' (''born at dawn or daylight'', maybe also ''shiny'', or ''of light complexion''). Alternative spellings are Luci, Luce, Lu ...

married the leading Whig politician and soldier General James Stanhope. From 1717 to 1721, Stanhope served as effective First Minister in the Stanhope–Sunderland Ministry, and was a useful political contact for the Pitt family until the collapse of the South Sea Bubble

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþaz ...

, a disaster which engulfed the government.

Birth and Education

William Pitt was born atGolden Square

Golden Square, in Soho, the City of Westminster, London, is a mainly hardscaped garden square planted with a few mature trees and raised borders in Central London flanked by classical office buildings. Its four approach ways are north and sou ...

, Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Bu ...

, on 15 November 1708. His older brother Thomas Pitt

Thomas Pitt (5 July 1653 – 28 April 1726) of Blandford St Mary in Dorset, later of Stratford in Wiltshire and of Boconnoc in Cornwall, known during life commonly as ''Governor Pitt'', as ''Captain Pitt'', or posthumously, as ''"Diamond" ...

had been born in 1704. There were also five sisters: Harriet, Catherine, Ann, Elizabeth, and Mary. From 1719 William was educated at Eton College

Eton College () is a public school in Eton, Berkshire, England. It was founded in 1440 by Henry VI under the name ''Kynge's College of Our Ladye of Eton besyde Windesore'',Nevill, p. 3 ff. intended as a sister institution to King's College, C ...

along with his brother. William disliked Eton, later claiming that "a public school

Public school may refer to:

* State school (known as a public school in many countries), a no-fee school, publicly funded and operated by the government

* Public school (United Kingdom), certain elite fee-charging independent schools in England an ...

might suit a boy of turbulent disposition but would not do where there was any gentleness". It was at school that Pitt began to suffer from gout

Gout ( ) is a form of inflammatory arthritis characterized by recurrent attacks of a red, tender, hot and swollen joint, caused by deposition of monosodium urate monohydrate crystals. Pain typically comes on rapidly, reaching maximal intensit ...

. Governor Pitt died in 1726, and the family estate at Boconnoc passed to William's father. When he died the following year, Boconnoc was inherited by William's elder brother, Thomas Pitt of Boconnoc

Thomas Pitt (''c.'' 1705 – 17 July 1761), of Boconnoc, Cornwall, was a British landowner and politician who sat in the House of Commons between 1727 and 1761. He was Lord Warden of the Stannaries from 1742 to 1751.

Pitt was the grandson an ...

.

In January 1727, William was entered as a gentleman commoner

A commoner is a student at certain universities in the British Isles who historically pays for his own tuition and commons, typically contrasted with scholars and exhibitioners, who were given financial emoluments towards their fees.

Cambridge

...

at Trinity College, Oxford

(That which you wish to be secret, tell to nobody)

, named_for = The Holy Trinity

, established =

, sister_college = Churchill College, Cambridge

, president = Dame Hilary Boulding

, location = Broad Street, Oxford OX1 3BH

, coordinates ...

. There is evidence that he was an extensive reader, if not a minutely accurate classical scholar. Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: t ...

was his favourite author. William diligently cultivated the faculty of expression by the practice of translation and re-translation. In these years he became a close friend of George Lyttelton, who would later become a leading politician. In 1728 a violent attack of gout compelled him to leave Oxford without finishing his degree. He then chose to travel abroad, from 1728 attending Utrecht University

Utrecht University (UU; nl, Universiteit Utrecht, formerly ''Rijksuniversiteit Utrecht'') is a public research university in Utrecht, Netherlands. Established , it is one of the oldest universities in the Netherlands. In 2018, it had an enrollme ...

in the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands (Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiography ...

, gaining a knowledge of Hugo Grotius

Hugo Grotius (; 10 April 1583 – 28 August 1645), also known as Huig de Groot () and Hugo de Groot (), was a Dutch humanist, diplomat, lawyer, theologian, jurist, poet and playwright.

A teenage intellectual prodigy, he was born in Delft ...

and other writers on international law and diplomacy. It is not known how long Pitt studied at Utrecht; by 1730 he had returned to his brother's estate at Boconnoc.

He had recovered from the attack of gout, but the disease proved intractable, and he continued to be subject to attacks of growing intensity at frequent intervals until his death.

Military career

On Pitt's return home it was necessary for him, as the younger son, to choose a profession and he opted for a career in the army. He obtained a

On Pitt's return home it was necessary for him, as the younger son, to choose a profession and he opted for a career in the army. He obtained a cornet

The cornet (, ) is a brass instrument similar to the trumpet but distinguished from it by its conical bore, more compact shape, and mellower tone quality. The most common cornet is a transposing instrument in B, though there is also a sopr ...

's commission in the dragoons with the King's Own Regiment of Horse (later 1st King's Dragoon Guards). George II George II or 2 may refer to:

People

* George II of Antioch (seventh century AD)

* George II of Armenia (late ninth century)

* George II of Abkhazia (916–960)

* Patriarch George II of Alexandria (1021–1051)

* George II of Georgia (1072–1089) ...

never forgot the jibes of "the terrible cornet of horse". It was reported that the £1,000 cost of the commission had been supplied by Robert Walpole

Robert Walpole, 1st Earl of Orford, (26 August 1676 – 18 March 1745; known between 1725 and 1742 as Sir Robert Walpole) was a British statesman and Whig politician who, as First Lord of the Treasury, Chancellor of the Exchequer, and Leader ...

, the prime minister, out of Treasury

A treasury is either

*A government department related to finance and taxation, a finance ministry.

*A place or location where treasure, such as currency or precious items are kept. These can be state or royal property, church treasure or i ...

funds in an attempt to secure the support of Pitt's brother Thomas in Parliament. Alternatively the fee may have been waived by the commanding officer of the regiment, Lord Cobham, who was related to the Pitt brothers by marriage.

Pitt was to grow close to Cobham, whom he regarded as almost a surrogate father. He was stationed for much of his service in Northampton

Northampton () is a market town and civil parish in the East Midlands of England, on the River Nene, north-west of London and south-east of Birmingham. The county town of Northamptonshire, Northampton is one of the largest towns in England; ...

, on peacetime duties. Pitt was particularly frustrated that, owing to Walpole's isolationist policies, Britain had not entered the War of the Polish Succession

The War of the Polish Succession ( pl, Wojna o sukcesję polską; 1733–35) was a major European conflict sparked by a Polish civil war over the succession to Augustus II of Poland, which the other regional power, European powers widened in p ...

which began in 1733, and he had not been able to test himself in battle. Pitt was granted extended leave in 1733, and toured France and Switzerland. He briefly visited Paris but spent most of his time in the French provinces, spending the winter in Lunéville

Lunéville ( ; German, obsolete: ''Lünstadt'' ) is a commune in the northeastern French department of Meurthe-et-Moselle.

It is a subprefecture of the department and lies on the river Meurthe at its confluence with the Vezouze.

History

Lun ...

in the Duchy of Lorraine

The Duchy of Lorraine (french: Lorraine ; german: Lothringen ), originally Upper Lorraine, was a duchy now included in the larger present-day region of Lorraine in northeastern France. Its capital was Nancy.

It was founded in 959 following t ...

.

Pitt's military career was destined to be relatively short. His elder brother Thomas was returned at the general election of 1734 for two separate seats, Okehampton

Okehampton ( ) is a town and civil parish in West Devon in the English county of Devon. It is situated at the northern edge of Dartmoor, and had a population of 5,922 at the 2011 census. Two electoral wards are based in the town (east and west) ...

and Old Sarum

Old Sarum, in Wiltshire, South West England, is the now ruined and deserted site of the earliest settlement of Salisbury. Situated on a hill about north of modern Salisbury near the A345 road, the settlement appears in some of the earliest re ...

, and chose to sit for Okehampton, passing the vacant seat to William who accordingly, in February 1735, entered parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

as member for Old Sarum. He became one of a large number of serving army officers in the House of Commons.

Rise to prominence

Patriot Whigs

Pitt soon joined a faction of discontented Whigs known as the Patriots who formed part of the opposition. The group commonly met at Stowe House, the country estate of Lord Cobham, who was a leader of the group. Cobham had originally been a supporter ofthe government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is a ...

under Sir Robert Walpole, but a dispute over the controversial Excise Bill

The Excise Bill of 1733 was a proposal by the British government of Robert Walpole to impose an excise tax on a variety of products. This would have allowed Customs officers to search private dwellings to look for contraband untaxed goods. The per ...

of 1733 had seen them join the opposition. Pitt swiftly became one of the faction's most prominent members.

Pitt's maiden speech

A maiden speech is the first speech given by a newly elected or appointed member of a legislature or parliament.

Traditions surrounding maiden speeches vary from country to country. In many Westminster system governments, there is a convention th ...

in the Commons was delivered in April 1736, in the debate on the congratulatory address to George II George II or 2 may refer to:

People

* George II of Antioch (seventh century AD)

* George II of Armenia (late ninth century)

* George II of Abkhazia (916–960)

* Patriarch George II of Alexandria (1021–1051)

* George II of Georgia (1072–1089) ...

on the marriage of his son Frederick, Prince of Wales

Frederick, Prince of Wales, (Frederick Louis, ; 31 January 170731 March 1751), was the eldest son and heir apparent of King George II of Great Britain. He grew estranged from his parents, King George and Queen Caroline. Frederick was the fath ...

. He used the occasion to pay compliments, and there was nothing striking in the speech as reported, but it helped to gain him the attention of the House when he later took part on debates on more partisan subjects. In particular, he attacked Britain's non-intervention in the ongoing European war, which he believed was in violation of the Treaty of Vienna and the terms of the Anglo-Austrian Alliance

The Anglo-Austrian Alliance connected the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Habsburg monarchy during the first half of the 18th century. It was largely the work of the British whig statesman Duke of Newcastle, who considered an alliance with Austri ...

.

He became such a troublesome critic of the government that Walpole moved to punish him by arranging his dismissal from the army in 1736, along with several of his friends and political allies. This provoked a wave of hostility to Walpole because many saw such an act as unconstitutional

Constitutionality is said to be the condition of acting in accordance with an applicable constitution; "Webster On Line" the status of a law, a procedure, or an act's accordance with the laws or set forth in the applicable constitution. When l ...

—that members of Parliament were being dismissed for their freedom of speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The right to freedom of expression has been recogni ...

in attacking the government, something protected by Parliamentary privilege. None of the men had their commissions reinstated, however, and the incident brought an end to Pitt's military career. The loss of Pitt's commission was soon compensated. The heir to the throne, Frederick, Prince of Wales

Frederick, Prince of Wales, (Frederick Louis, ; 31 January 170731 March 1751), was the eldest son and heir apparent of King George II of Great Britain. He grew estranged from his parents, King George and Queen Caroline. Frederick was the fath ...

, was involved in a long-running dispute with his father, George II, and was the patron of the opposition

Opposition may refer to:

Arts and media

* ''Opposition'' (Altars EP), 2011 EP by Christian metalcore band Altars

* The Opposition (band), a London post-punk band

* '' The Opposition with Jordan Klepper'', a late-night television series on Com ...

. He appointed Pitt one of his Grooms of the Bedchamber as a reward. In this new position his hostility to the government did not in any degree relax, and his oratorical gifts were substantial.

War

Spanish war

During the 1730s Britain's relationship with Spain had slowly declined. Repeated cases of reported Spanish mistreatment of British merchants, whom they accused of smuggling, caused public outrage, particularly the incident of Jenkins' Ear. Pitt was a leading advocate of a more hard-line policy against Spain, and often castigated Walpole's government for its weakness in dealing withMadrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

. Pitt spoke out against the Convention of El Pardo which aimed to settle the dispute peacefully. In the speech against the Convention in the House of Commons on 8 March 1739 Pitt said:

When trade is at stake, it is your last entrenchment; you must defend it, or perish ... Sir, Spain knows the consequence of a war in America; whoever gains, it must prove fatal to her ... is this any longer a nation? Is this any longer an English Parliament, if with more ships in your harbours than in all the navies of Europe; with above two millions of people in your American colonies, you will bear to hear of the expediency of receiving from Spain an insecure, unsatisfactory, dishonourable Convention?Owing to public pressure, the British government was pushed towards declaring war with Spain in 1739. Britain began with a success at Porto Bello. However the war effort soon stalled, and Pitt alleged that the government was not prosecuting the war effectively—demonstrated by the fact that the British waited two years before taking further offensive action fearing that further British victories would provoke the French into declaring war. When they did so, a failed attack was made on the South American port of Cartagena which left thousands of British troops dead, over half from disease, and cost many ships. The decision to attack during the

rainy season

The rainy season is the time of year when most of a region's average annual rainfall occurs.

Rainy Season may also refer to:

* ''Rainy Season'' (short story), a 1989 short horror story by Stephen King

* "Rainy Season", a 2018 song by Monni

* ''T ...

was held as further evidence of the government's incompetence.

After this, the colonial war against Spain was almost entirely abandoned as British resources were switched towards fighting France in Europe as the War of the Austrian Succession

The War of the Austrian Succession () was a European conflict that took place between 1740 and 1748. Fought primarily in Central Europe, the Austrian Netherlands, Italy, the Atlantic and Mediterranean, related conflicts included King George's W ...

had broken out. The Spanish had repelled a major invasion intended to conquer Central America and succeeded in maintaining their trans-Atlantic convoys while causing much disruption to British shipping and twice broke a British blockade to land troops in Italy, but the war with Spain was treated as a draw. Many of the underlying issues remained unresolved by the later peace treaties leaving the potential for future conflicts to occur. Pitt considered the war a missed opportunity to take advantage of a power in decline, although later he became an advocate of warmer relations with the Spanish in an effort to prevent them forming an alliance with France.

Hanover

Walpole and Newcastle were now giving the war in Europe a much higher priority than the colonial conflict with Spain in the Americas.

Walpole and Newcastle were now giving the war in Europe a much higher priority than the colonial conflict with Spain in the Americas. Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

and Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

went to war in 1740, with many other European states soon joining in. There was a fear that France would launch an invasion of Hanover

Hanover (; german: Hannover ; nds, Hannober) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Lower Saxony. Its 535,932 (2021) inhabitants make it the 13th-largest city in Germany as well as the fourth-largest city in Northern Germany ...

, which was linked to Britain through the crown of George II George II or 2 may refer to:

People

* George II of Antioch (seventh century AD)

* George II of Armenia (late ninth century)

* George II of Abkhazia (916–960)

* Patriarch George II of Alexandria (1021–1051)

* George II of Georgia (1072–1089) ...

. To avert this Walpole and Newcastle decided to pay a large subsidy

A subsidy or government incentive is a form of financial aid or support extended to an economic sector (business, or individual) generally with the aim of promoting economic and social policy. Although commonly extended from the government, the ter ...

to both Austria and Hanover, in order for them to raise troops and defend themselves.

Pitt now launched an attack on such subsidies, playing to widespread anti-Hanoverian feelings in Britain. This boosted his popularity with the public, but earned him the lifelong hatred of the King, who was emotionally committed to Hanover, where he had spent the first thirty years of his life. In response to Pitt's attacks, the British government decided not to pay a direct subsidy to Hanover, but instead to pass the money indirectly through Austriaa move which was considered more politically acceptable. A sizeable Anglo-German army was formed which George II himself led to victory at the Battle of Dettingen

The Battle of Dettingen (german: Schlacht bei Dettingen) took place on 27 June 1743 during the War of the Austrian Succession at Dettingen in the Electorate of Mainz, Holy Roman Empire (now Karlstein am Main in Bavaria). It was fought between a ...

in 1743, reducing the immediate threat to Hanover.

Fall of Walpole

Many of Pitt's attacks on the government were directed personally at Walpole who had now been Prime Minister for twenty years. He spoke in favour of the motion in 1742 for aninquiry

An inquiry (also spelled as enquiry in British English) is any process that has the aim of augmenting knowledge, resolving doubt, or solving a problem. A theory of inquiry is an account of the various types of inquiry and a treatment of the ...

into the last ten years of Walpole's administration. In February 1742, following poor election results and the disaster at Cartagena, Walpole was at last forced to succumb to the long-continued attacks of opposition, resigned and took a peerage

A peerage is a legal system historically comprising various hereditary titles (and sometimes non-hereditary titles) in a number of countries, and composed of assorted noble ranks.

Peerages include:

Australia

* Australian peers

Belgium

* Belgi ...

.

Pitt now expected a new government to be formed led by Pulteney and dominated by Tories

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. Th ...

and Patriot Whigs

The Patriot Whigs, later the Patriot Party, were a group within the Whig Party in Great Britain from 1725 to 1803. The group was formed in opposition to the government of Robert Walpole in the House of Commons in 1725, when William Pulteney (l ...

in which he could expect a junior position. Walpole was instead succeeded as Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

by Lord Wilmington

Spencer Compton, 1st Earl of Wilmington, (2 July 1743) was a British Whig statesman who served continuously in government from 1715 until his death. He sat in the English and British House of Commons between 1698 and 1728, and was then raise ...

, though the real power in the new government was divided between Lord Carteret

John Carteret, 2nd Earl Granville, 7th Seigneur of Sark, (; 22 April 16902 January 1763), commonly known by his earlier title Lord Carteret, was a British statesman and Lord President of the Council from 1751 to 1763; he worked extremely clos ...

and the Pelham brothers (Henry

Henry may refer to:

People

*Henry (given name)

* Henry (surname)

* Henry Lau, Canadian singer and musician who performs under the mononym Henry

Royalty

* Portuguese royalty

** King-Cardinal Henry, King of Portugal

** Henry, Count of Portugal, ...

and Thomas, Duke of Newcastle). Walpole had carefully orchestrated this new government as a continuance of his own, and continued to advise it up to his death in 1745. Pitt's hopes for a place in the government were thwarted, and he remained in opposition. He was therefore unable to make any personal gain from the downfall of Walpole, to which he had personally contributed a great deal.

The administration formed by the Pelhams in 1744, after the dismissal of Carteret, included many of Pitt's former Patriot allies, but Pitt was not granted a position because of continued ill-feeling by the King and leading Whigs about his views on Hanover. In 1744 Pitt received a large boost to his personal fortune when the Dowager Duchess of Marlborough died leaving him a legacy

In law, a legacy is something held and transferred to someone as their inheritance, as by will and testament. Personal effects, family property, marriage property or collective property gained by will of real property.

Legacy or legacies may refer ...

of £10,000 as an "acknowledgment of the noble defence he had made for the support of the laws of England and to prevent the ruin of his country". It was probably as much a mark of her dislike of Walpole as of her admiration of Pitt.

In Government

Paymaster of the Forces

Reluctantly the King finally agreed to give Pitt a place in the government. Pitt had changed his stance on a number of issues to make himself more acceptable to George, most notably the heated issue of Hanoverian subsidies. To force the matter, the Pelham brothers had to resign on the question whether he should be admitted or not, and it was only after all other arrangements had proved impracticable, that they were reinstated with Pitt appointed asVice Treasurer of Ireland

A vice is a practice, behaviour, or Habit (psychology), habit generally considered immorality, immoral, sinful, crime, criminal, rude, taboo, depraved, degrading, deviant or perverted in the associated society. In more minor usage, vice can refe ...

in February 1746. George continued to resent him however.

In May of the same year Pitt was promoted to the more important and lucrative office of paymaster-general

His Majesty's Paymaster General or HM Paymaster General is a ministerial position in the Cabinet Office of the United Kingdom. The incumbent Paymaster General is Jeremy Quin MP.

History

The post was created in 1836 by the merger of the posit ...

, which gave him a place in the Privy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mon ...

, though not in the cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filing ...

. Here he had an opportunity of displaying his public spirit and integrity in a way that deeply impressed both the king and the country. It had been the usual practise of previous paymasters to appropriate to themselves the interest of all money lying in their hands by way of advance, and also to accept a commission of % on all foreign subsidies. Although there was no strong public sentiment against the practice, Pitt completely refused to profit by it. All advances were lodged by him in the Bank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694 to act as the English Government's banker, and still one of the bankers for the Government of ...

until required, and all subsidies were paid over without deduction, even though it was pressed upon him, so that he did not draw a shilling

The shilling is a historical coin, and the name of a unit of modern currencies formerly used in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, other British Commonwealth countries and Ireland, where they were generally equivalent to 12 pence o ...

from his office beyond the salary

A salary is a form of periodic payment from an employer to an employee, which may be specified in an employment contract. It is contrasted with piece wages, where each job, hour or other unit is paid separately, rather than on a periodic basis.

...

legally attaching to it. Pitt ostentatiously made this clear to everyone, although he was in fact following what Henry Pelham

Henry Pelham (25 September 1694 – 6 March 1754) was a British Whig statesman who served as 3rd Prime Minister of Great Britain from 1743 until his death in 1754. He was the younger brother of Thomas Pelham-Holles, 1st Duke of Newcastle, who ...

had done when he had held the post between 1730 and 1743. This helped to establish Pitt's reputation with the British people for honesty and placing the interests of the nation before his own.

The administration formed in 1746 lasted without major changes until 1754. It would appear from his published correspondence that Pitt had a greater influence in shaping its policy than his comparatively subordinate position would in itself have entitled him to. His support for measures, such as the Spanish Treaty and the continental subsidies, which he had violently denounced when in opposition was criticised by his enemies as an example of his political opportunism

Opportunism is the practice of taking advantage of circumstances – with little regard for principles or with what the consequences are for others. Opportunist actions are expedient actions guided primarily by self-interested motives. The term ...

.

Between 1746 and 1748 Pitt worked closely with Newcastle in formulating British military and diplomatic strategy. He shared with Newcastle a belief that Britain should continue to fight until it could receive generous peace terms, in contrast to some such as Henry Pelham

Henry Pelham (25 September 1694 – 6 March 1754) was a British Whig statesman who served as 3rd Prime Minister of Great Britain from 1743 until his death in 1754. He was the younger brother of Thomas Pelham-Holles, 1st Duke of Newcastle, who ...

who favoured an immediate peace. Pitt was personally saddened when his friend and brother-in-law Thomas Grenville

Thomas Grenville (31 December 1755 – 17 December 1846) was a British politician and bibliophile.

Background and education

Grenville was the second son of Prime Minister George Grenville and Elizabeth Wyndham, daughter of Sir William Wynd ...

was killed at the naval First Battle of Cape Finisterre

The First Battle of Cape Finisterre (14 May 1747in the Julian calendar then in use in Britain this was 3 May 1747) was waged during the War of the Austrian Succession. It refers to the attack by 14 British ships of the line under Admiral Georg ...

in 1747. However, this victory helped secure British supremacy of the sea which gave the British a stronger negotiating position when it came to the peace talks that ended the war. At the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748 British colonial conquests were exchanged for a French withdrawal from Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

. Many saw this as merely an armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the La ...

and awaited an imminent new war.

Dispute with Newcastle

In 1754, Henry Pelham died suddenly, and was succeeded as Prime Minister by his brother, the Duke of Newcastle. As Newcastle sat in theHouse of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the Bicameralism, upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by Life peer, appointment, Hereditary peer, heredity or Lords Spiritual, official function. Like the ...

, he required a leading politician to represent the government in the House of Commons. Pitt and Henry Fox were considered the two favourites for the position, but Newcastle instead rejected them both and turned to the less well-known figure of Sir Thomas Robinson Thomas, Tom or Tommy Robinson may refer to:

Artists

* Thomas Robinson (composer) (c. 1560 – after 1609), English composer and music teacher

* Thomas Heath Robinson (1869–1954), British book illustrator

Politicians

* Thomas Robinson, 1st Baron ...

, a career diplomat

A diplomat (from grc, δίπλωμα; romanized ''diploma'') is a person appointed by a state or an intergovernmental institution such as the United Nations or the European Union to conduct diplomacy with one or more other states or internati ...

, to fill the post. It was widely believed that Newcastle had done this because he feared the ambitions of both Pitt and Fox, and believed he would find it easier to dominate the inexperienced Robinson.

Despite his disappointment there was no immediate open breach. Pitt continued at his post; and at the general election which took place during the year he even accepted a nomination for the Duke's

Despite his disappointment there was no immediate open breach. Pitt continued at his post; and at the general election which took place during the year he even accepted a nomination for the Duke's pocket borough

A rotten or pocket borough, also known as a nomination borough or proprietorial borough, was a parliamentary borough or constituency in England, Great Britain, or the United Kingdom before the Reform Act 1832, which had a very small electorat ...

of Aldborough. He had sat for Seaford since 1747. The government won a landslide

Landslides, also known as landslips, are several forms of mass wasting that may include a wide range of ground movements, such as rockfalls, deep-seated grade (slope), slope failures, mudflows, and debris flows. Landslides occur in a variety of ...

, further strengthening its majority in parliament.

When parliament met, however, he made no secret of his feelings. Ignoring Robinson, Pitt made frequent and vehement attacks on Newcastle himself, though still continued to serve as Paymaster under him. From 1754 Britain was increasingly drawn into conflict with France during this period, despite Newcastle's wish to maintain the peace. The countries clashed in North America, where each had laid claim to the Ohio Country. A British expedition under General Braddock had been despatched and defeated in summer 1755 which caused a ratcheting up of tensions.

Eager to prevent the war spreading to Europe, Newcastle now tried to conclude a series of treaties that would secure Britain allies through the payment of subsidies, which he hoped would discourage France from attacking Britain. Similar subsidies had been an issue of past disagreement, and they were widely attacked by Patriot Whigs and Tories. As the government came under increasing attack, Newcastle replaced Robinson with Fox who it was acknowledged carried more political weight and again slighted Pitt.

Finally in November 1755, Pitt was dismissed from office as paymaster, having spoken during a debate at great length against the new system of continental subsidies proposed by the government of which he was still a member. Fox retained his own place, and though the two men continued to be of the same party, and afterwards served again in the same government, there was henceforward a rivalry between them, which makes the celebrated opposition of their sons,

Eager to prevent the war spreading to Europe, Newcastle now tried to conclude a series of treaties that would secure Britain allies through the payment of subsidies, which he hoped would discourage France from attacking Britain. Similar subsidies had been an issue of past disagreement, and they were widely attacked by Patriot Whigs and Tories. As the government came under increasing attack, Newcastle replaced Robinson with Fox who it was acknowledged carried more political weight and again slighted Pitt.

Finally in November 1755, Pitt was dismissed from office as paymaster, having spoken during a debate at great length against the new system of continental subsidies proposed by the government of which he was still a member. Fox retained his own place, and though the two men continued to be of the same party, and afterwards served again in the same government, there was henceforward a rivalry between them, which makes the celebrated opposition of their sons, William Pitt the Younger

William Pitt the Younger (28 May 175923 January 1806) was a British statesman, the youngest and last prime minister of Great Britain (before the Acts of Union 1800) and then first prime minister of the United Kingdom (of Great Britain and Ire ...

and Charles James Fox

Charles James Fox (24 January 1749 – 13 September 1806), styled ''The Honourable'' from 1762, was a prominent British Whig statesman whose parliamentary career spanned 38 years of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. He was the arch-riv ...

, seem like an inherited quarrel.

Pitt's relationship with the Duke slumped further in early 1756 when he alleged that Newcastle was deliberately leaving the island of Menorca

Menorca or Minorca (from la, Insula Minor, , smaller island, later ''Minorica'') is one of the Balearic Islands located in the Mediterranean Sea belonging to Spain. Its name derives from its size, contrasting it with nearby Majorca. Its capi ...

ill-defended so that the French would seize it, and Newcastle could use its loss to prove that Britain was not able to fight a war against France and sue for peace. When in June 1756 Menorca fell after a failed attempt by Admiral Byng to relieve it, Pitt's allegations fuelled the public anger against Newcastle, leading him to be attacked by a mob in Greenwich

Greenwich ( , ,) is a town in south-east London, England, within the ceremonial county of Greater London. It is situated east-southeast of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime history and for giving its name to the Greenwich ...

. The loss of Menorca shattered public faith in Newcastle, and forced him to step down as Prime Minister in November 1756.

Secretary of State

In December 1756, Pitt, who now sat for

In December 1756, Pitt, who now sat for Okehampton

Okehampton ( ) is a town and civil parish in West Devon in the English county of Devon. It is situated at the northern edge of Dartmoor, and had a population of 5,922 at the 2011 census. Two electoral wards are based in the town (east and west) ...

, became Secretary of State for the Southern Department

The Secretary of State for the Southern Department was a position in the cabinet of the government of the Kingdom of Great Britain up to 1782, when the Southern Department became the Home Office.

History

Before 1782, the responsibilities of ...

, and Leader of the House of Commons

The leader of the House of Commons is a minister of the Crown of the Government of the United Kingdom whose main role is organising government business in the House of Commons. The leader is generally a member or attendee of the cabinet of the ...

under the premiership of the Duke of Devonshire. Upon entering this coalition, Pitt said to Devonshire: "My Lord, I am sure I can save this country, and no one else can".