William Morrison, 1st Viscount Dunrossil on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

William Shepherd Morrison, 1st Viscount Dunrossil, (10 August 1893 – 3 February 1961), was a British politician. He was a long-serving cabinet minister before serving as

Morrison held the post of Speaker until 1959, when he announced that he would not be contesting the forthcoming general election but retiring for reasons of health. As was customary for former Speakers, he was made a Viscount, taking the title Viscount Dunrossil, of Vallaquie in the Isle of North Uist and County of Inverness. Given his health, it surprised many when it was announced shortly thereafter that he had been chosen to succeed Sir William Slim as

Morrison held the post of Speaker until 1959, when he announced that he would not be contesting the forthcoming general election but retiring for reasons of health. As was customary for former Speakers, he was made a Viscount, taking the title Viscount Dunrossil, of Vallaquie in the Isle of North Uist and County of Inverness. Given his health, it surprised many when it was announced shortly thereafter that he had been chosen to succeed Sir William Slim as

Morrison was unusual in having separate, and entirely different, grants of arms from both the College of Arms in England and the Lyon Court in Scotland.

Morrison was unusual in having separate, and entirely different, grants of arms from both the College of Arms in England and the Lyon Court in Scotland.

ADB Entry

{{DEFAULTSORT:Dunrossil, William Morrison, 1st Viscount 1893 births 1961 deaths Morrison, William Alumni of the University of Edinburgh British Army personnel of World War I English King's Counsel Chairmen of the 1922 Committee Morrison, William Morrison, William Conservative Party (UK) hereditary peers Governors-General of Australia Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Ministers in the Chamberlain peacetime government, 1937–1939 Ministers in the Chamberlain wartime government, 1939–1940 Ministers in the Churchill caretaker government, 1945 Ministers in the Churchill wartime government, 1940–1945 Viscounts created by Elizabeth II People educated at George Watson's College Politicians awarded knighthoods Recipients of the Military Cross Royal Artillery officers Morrison, William Morrison, William Morrison, William Morrison, William Morrison, William Morrison, William Morrison, William Morrison, William UK MPs who were granted peerages Morrison, William Viscounts in the Peerage of the United Kingdom British King's Counsel

Speaker of the House of Commons Speaker of the House of Commons is a political leadership position found in countries that have a House of Commons, where the membership of the body elects a speaker to lead its proceedings.

Systems that have such a position include:

* Speaker of ...

from 1951 to 1959. He was then appointed as the 14th Governor-General of Australia

The governor-general of Australia is the representative of the monarch, currently King Charles III, in Australia.Torinturk

Torinturk () is a village in Argyll and Bute, Scotland.

Torinturk is from Tarbert. Torinturk comes from the Gaelic for the hill of the boar. This is where the last wild boar

The wild boar (''Sus scrofa''), also known as the wild swine ...

, Argyll

Argyll (; archaically Argyle, in modern Gaelic, ), sometimes called Argyllshire, is a historic county and registration county of western Scotland.

Argyll is of ancient origin, and corresponds to most of the part of the ancient kingdom of ...

. He attended George Watson's College

George Watson's College is a co-educational Independent school (United Kingdom), independent day school in Scotland, situated on Colinton Road, in the Merchiston area of Edinburgh. It was first established as a Scottish education in the eight ...

and then went on to the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

; his studies were interrupted by World War I, where he served with the Royal Field Artillery and won the Military Cross

The Military Cross (MC) is the third-level (second-level pre-1993) military decoration awarded to officers and (since 1993) other ranks of the British Armed Forces, and formerly awarded to officers of other Commonwealth countries.

The MC i ...

. Training as a lawyer, Morrison was called to the bar

The call to the bar is a legal term of art in most common law jurisdictions where persons must be qualified to be allowed to argue in court on behalf of another party and are then said to have been "called to the bar" or to have received "call to ...

in 1923 and began working as a private secretary to Thomas Inskip

Thomas Walker Hobart Inskip, 1st Viscount Caldecote, (5 March 1876 – 11 October 1947) was a British politician who served in many legal posts, culminating in serving as Lord Chancellor from 1939 until 1940. Despite legal posts dominating his ...

, the Solicitor General. After several previous attempts, he was elected to the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

in 1929, representing a constituency in Gloucestershire

Gloucestershire ( abbreviated Glos) is a county in South West England. The county comprises part of the Cotswold Hills, part of the flat fertile valley of the River Severn and the entire Forest of Dean.

The county town is the city of Gl ...

for the Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

.

In 1936, after several years as a junior minister

A minister is a politician who heads a ministry, making and implementing decisions on policies in conjunction with the other ministers. In some jurisdictions the head of government is also a minister and is designated the ‘prime minister’, � ...

, Morrison was made Minister of Agriculture and Fisheries

The Minister of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food was a United Kingdom cabinet position, responsible for the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food. The post was originally named President of the Board of Agriculture and was created in 1889. ...

by Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, (3 August 186714 December 1947) was a British Conservative Party politician who dominated the government of the United Kingdom between the world wars, serving as prime minister on three occasions, ...

. He also served as a minister under Neville Chamberlain and Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

, including as Minister of Food

The Minister of Food Control (1916–1921) and the Minister of Food (1939–1958) were British government ministerial posts separated from that of the Minister of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, Minister of Agriculture. In the Great War the Minist ...

(1939–1940), Postmaster General

A Postmaster General, in Anglosphere countries, is the chief executive officer of the postal service of that country, a ministerial office responsible for overseeing all other postmasters. The practice of having a government official responsib ...

(1940–1943), and Minister of Town and Country Planning (1943–1945). Morrison was elevated to the speakership following the 1951 general election. He was praised for his impartiality, especially during the heated debate on the Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, or the Second Arab–Israeli war, also called the Tripartite Aggression ( ar, العدوان الثلاثي, Al-ʿUdwān aṯ-Ṯulāṯiyy) in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel,Also known as the Suez War or 1956 Wa ...

, and was raised to the viscountcy when his term ended. Lord Dunrossil became governor-general in 1960, on the nomination of Robert Menzies

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of ''Hrōþ, Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory ...

, but served only a year before dying in office.

Early life

Morrison was born inTorinturk

Torinturk () is a village in Argyll and Bute, Scotland.

Torinturk is from Tarbert. Torinturk comes from the Gaelic for the hill of the boar. This is where the last wild boar

The wild boar (''Sus scrofa''), also known as the wild swine ...

, Argyll

Argyll (; archaically Argyle, in modern Gaelic, ), sometimes called Argyllshire, is a historic county and registration county of western Scotland.

Argyll is of ancient origin, and corresponds to most of the part of the ancient kingdom of ...

, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

, the son of Marion (née McVicar) and John Morrison. His father was a farmer who had previously spent time working in South Africa's diamond industry. Morrison was educated at George Watson's College

George Watson's College is a co-educational Independent school (United Kingdom), independent day school in Scotland, situated on Colinton Road, in the Merchiston area of Edinburgh. It was first established as a Scottish education in the eight ...

and the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

. He joined the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

as an officer in the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

and served with an artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

regiment in France, where he won the Military Cross

The Military Cross (MC) is the third-level (second-level pre-1993) military decoration awarded to officers and (since 1993) other ranks of the British Armed Forces, and formerly awarded to officers of other Commonwealth countries.

The MC i ...

. In 1919 he left the Army with the rank of captain. He married Katharine Swan in 1924, with whom he had four sons.

Political career

Morrison was elected to theHouse of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

as Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization i ...

Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

(MP) for Cirencester and Tewkesbury

Cirencester and Tewkesbury was a parliamentary constituency in Gloucestershire which returned one Member of Parliament (MP) to the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It was created for the 1918 general election and abolish ...

in 1929. In Parliament he acquired the nickname "Shakes", from his habit of quoting from the works of William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

.

Government minister

Morrison had a long ministerial career under four Prime Ministers ( Ramsay MacDonald,Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, (3 August 186714 December 1947) was a British Conservative Party politician who dominated the government of the United Kingdom between the world wars, serving as prime minister on three occasions, ...

, Neville Chamberlain and Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

).

He was:

* Parliamentary Secretary to the Attorney-General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

1931–35,

* Financial Secretary to the Treasury

The financial secretary to the Treasury is a mid-level ministerial post in HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. It is nominally the fifth most significant ministerial role within the Treasury after the First Lord of the Treasury, first lord of th ...

1935–36,

* Minister of Agriculture and Fisheries

The Minister of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food was a United Kingdom cabinet position, responsible for the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food. The post was originally named President of the Board of Agriculture and was created in 1889. ...

1936–39,

* Minister of Food

The Minister of Food Control (1916–1921) and the Minister of Food (1939–1958) were British government ministerial posts separated from that of the Minister of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, Minister of Agriculture. In the Great War the Minist ...

1939–40,

* Postmaster-General

A Postmaster General, in Anglosphere countries, is the chief executive officer of the postal service of that country, a Ministry (government department), ministerial office responsible for overseeing all other postmasters. The practice of having ...

1940–43

* Minister for Town and Country Planning

Minister may refer to:

* Minister (Christianity), a Christian cleric

** Minister (Catholic Church)

* Minister (government), a member of government who heads a ministry (government department)

** Minister without portfolio, a member of government w ...

1943–45.

Morrison was referred to in the book "Guilty Men

''Guilty Men'' is a short book published in Great Britain in July 1940 that attacked British public figures for their failure to re-arm and their appeasement of Nazi Germany in the 1930s. A classic denunciation of the former government policy, i ...

" by Michael Foot

Michael Mackintosh Foot (23 July 19133 March 2010) was a British Labour Party politician who served as Labour Leader from 1980 to 1983. Foot began his career as a journalist on ''Tribune'' and the ''Evening Standard''. He co-wrote the 1940 p ...

, Frank Owen and Peter Howard (writing under the pseudonym 'Cato'), published in 1940 as an attack on public figures for their failure to re-arm and their appeasement of Nazi Germany. However, as noted in the diaries of Chips Channon, he was part of the Insurgents, the faction of the Conservative party that worked in secret against appeasement, to oust Chamberlain and replace him with Churchill ahead of the war.

Campaigning during the general election of 1945, Morrison attacked Socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

and pointed out that Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and then ...

and Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

began as Socialists. He further claimed that although Labour objected to the Conservatives calling themselves 'National', the Conservatives had no objection in their opponents labelling themselves National-Socialists. In 1947 he attacked identity card

An identity document (also called ID or colloquially as papers) is any documentation, document that may be used to prove a person's identity. If issued in a small, standard credit card size form, it is usually called an identity card (IC, ID c ...

s which had been introduced during the war because he believed they were a nuisance to law-abiding people and also because the cards were ineffective.

Speaker of the House of Commons

In 1951, when the Conservatives returned to power, Morrison waselected Elected may refer to:

* "Elected" (song), by Alice Cooper, 1973

* ''Elected'' (EP), by Ayreon, 2008

*The Elected, an American indie rock band

See also

*Election

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population ...

Speaker of the House of Commons Speaker of the House of Commons is a political leadership position found in countries that have a House of Commons, where the membership of the body elects a speaker to lead its proceedings.

Systems that have such a position include:

* Speaker of ...

. He was opposed by Labour

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

MP Major James Milner

James Philip Milner (born 4 January 1986) is an English professional footballer who plays as a midfielder for club Liverpool. A versatile player, Milner has played in multiple positions, including on the wing, in midfield and at full-back.

...

, who said it was his party's turn to have a Speaker of the House. It was the first contested election for the post in the twentieth century. Morrison was elected in a vote on party lines.

Governor-General of Australia

Morrison held the post of Speaker until 1959, when he announced that he would not be contesting the forthcoming general election but retiring for reasons of health. As was customary for former Speakers, he was made a Viscount, taking the title Viscount Dunrossil, of Vallaquie in the Isle of North Uist and County of Inverness. Given his health, it surprised many when it was announced shortly thereafter that he had been chosen to succeed Sir William Slim as

Morrison held the post of Speaker until 1959, when he announced that he would not be contesting the forthcoming general election but retiring for reasons of health. As was customary for former Speakers, he was made a Viscount, taking the title Viscount Dunrossil, of Vallaquie in the Isle of North Uist and County of Inverness. Given his health, it surprised many when it was announced shortly thereafter that he had been chosen to succeed Sir William Slim as Governor-General of Australia

The governor-general of Australia is the representative of the monarch, currently King Charles III, in Australia.Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is a British order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George IV, Prince of Wales, while he was acting as prince regent for his father, King George III.

It is named in honour ...

(GCMG) that year. By this time support for the idea of British governors-general was declining in Australia, but the Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

, Robert Menzies

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of ''Hrōþ, Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory ...

, was determined to maintain the British link (and, in particular, the Scottish link).

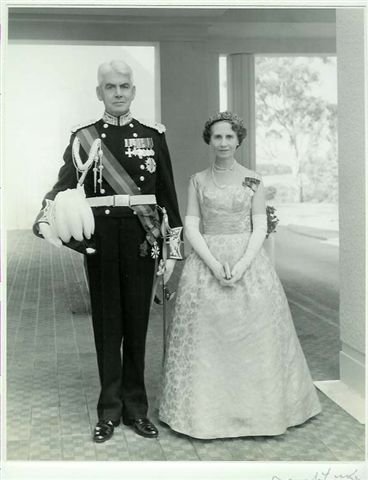

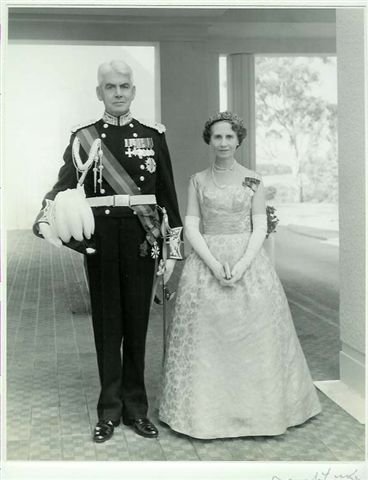

Dunrossil took office on 2 February 1960. He was the first governor-general since Isaac Isaacs

Sir Isaac Alfred Isaacs (6 August 1855 – 11 February 1948) was an Australian lawyer, politician, and judge who served as the ninth Governor-General of Australia, in office from 1931 to 1936. He had previously served on the High Court of Au ...

(1931–1936) to wear the full ceremonial vice-regal uniform, but despite this was known for having a more relaxed approach than his predecessor. Dunrossil suffered from ill health while in office, and his wife frequently deputised for him at ceremonial events. He suffered a pulmonary embolism

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is a blockage of an pulmonary artery, artery in the lungs by a substance that has moved from elsewhere in the body through the bloodstream (embolism). Symptoms of a PE may include dyspnea, shortness of breath, chest pain p ...

on the morning of 3 February 1961, becoming the first and only governor-general to die in office. He was granted a state funeral

A state funeral is a public funeral ceremony, observing the strict rules of Etiquette, protocol, held to honour people of national significance. State funerals usually include much pomp and ceremony as well as religious overtones and distinctive ...

, and buried at St John the Baptist Church, Reid

St John the Baptist Church is an Australian Anglican church in the Canberra suburb of Reid in the Australian Capital Territory. The church is located at the corner of Anzac Parade and Constitution Avenue, adjacent to the Parliamentary Triangl ...

. His Official Secretary throughout his term was Murray Tyrrell

Sir Murray Louis Tyrrell (1 December 1913 – 13 July 1994) was an Australian public servant, noted as the Official Secretary to the Governor-General of Australia for a record term of 26 years, 1947–73, in which time he served six governor ...

.

Dunrossil was succeeded in the viscountcy by his son, John Morrison, 2nd Viscount Dunrossil

Flight Lieutenant John William Morrison, 2nd Viscount Dunrossil (22 May 1926 – 22 March 2000) was a British diplomat. Lord Dunrossil was British High Commissioner to Fiji, Nauru and Tuvalu and later to Barbados. His career reached its ...

, who was a career officer in the Foreign & Commonwealth Office, holding several senior diplomatic appointments, including serving as Governor of Bermuda. He was proud to wear his father's vice-regal hat on formal occasions on the island colony.

Honours, decorations and arms

Notes

External links

*ADB Entry

{{DEFAULTSORT:Dunrossil, William Morrison, 1st Viscount 1893 births 1961 deaths Morrison, William Alumni of the University of Edinburgh British Army personnel of World War I English King's Counsel Chairmen of the 1922 Committee Morrison, William Morrison, William Conservative Party (UK) hereditary peers Governors-General of Australia Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Ministers in the Chamberlain peacetime government, 1937–1939 Ministers in the Chamberlain wartime government, 1939–1940 Ministers in the Churchill caretaker government, 1945 Ministers in the Churchill wartime government, 1940–1945 Viscounts created by Elizabeth II People educated at George Watson's College Politicians awarded knighthoods Recipients of the Military Cross Royal Artillery officers Morrison, William Morrison, William Morrison, William Morrison, William Morrison, William Morrison, William Morrison, William Morrison, William UK MPs who were granted peerages Morrison, William Viscounts in the Peerage of the United Kingdom British King's Counsel