William Goebel on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

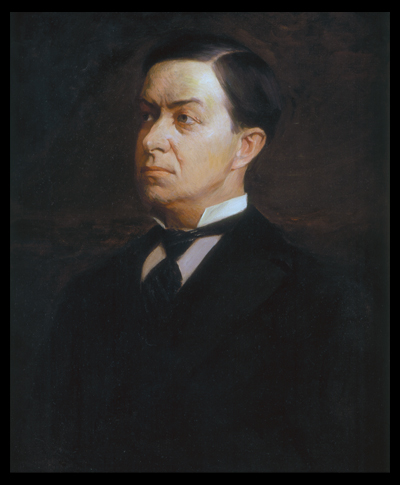

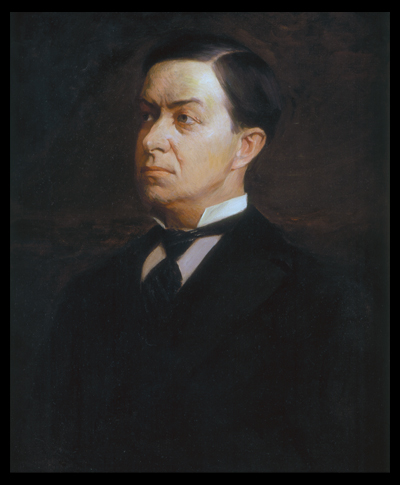

William Justus Goebel (January 4, 1856 – February 3, 1900) was an American Democratic politician who served as the 34th

In 1887, James William Bryan vacated his seat in the

In 1887, James William Bryan vacated his seat in the

In 1895, Goebel engaged in what many observers considered to be a

In 1895, Goebel engaged in what many observers considered to be a

governor of Kentucky

The governor of the Commonwealth of Kentucky is the head of government of Kentucky. Sixty-two men and one woman have served as governor of Kentucky. The governor's term is four years in length; since 1992, incumbents have been able to seek re-e ...

for four days in 1900, having been sworn in on his deathbed a day after being shot by an assassin. Goebel remains the only state governor in the United States to ever be assassinated while in office.

Goebel was born to Wilhelm and Augusta Goebel (), German immigrants from Hanover

Hanover (; german: Hannover ; nds, Hannober) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Lower Saxony. Its 535,932 (2021) inhabitants make it the 13th-largest city in Germany as well as the fourth-largest city in Northern Germany ...

. He studied at the Hollingsworth Business College in the mid-1870s and became an apprentice in John W. Stevenson's law firm. While Goebel lacked the social qualities like public speaking, which were common to politicians, various authors referred to him as an intellectual man. He served in the Kentucky Senate

The Kentucky Senate is the upper house of the Kentucky General Assembly. The Kentucky Senate is composed of 38 members elected from single-member districts throughout the Commonwealth. There are no term limits for Kentucky Senators. The Kentu ...

, campaigning for populist

Populism refers to a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of "the people" and often juxtapose this group against " the elite". It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term develop ...

causes like railroad regulation, which won him many allies and supporters.

In 1895, Goebel engaged in a duel

A duel is an arranged engagement in combat between two people, with matched weapons, in accordance with agreed-upon rules.

During the 17th and 18th centuries (and earlier), duels were mostly single combats fought with swords (the rapier and ...

with John Lawrence Sanford, a former Confederate general staff officer turned cashier. According to the witnesses, both men then drew their pistols, but no one was sure who fired first. Sanford was killed; Goebel pleaded self-defense and was acquitted.

During the 1899 Kentucky gubernatorial election

The 1899 Kentucky gubernatorial election was held on November 7, 1899, to choose the 33rd governor of Kentucky. The incumbent, Republican William O'Connell Bradley, was term-limited and unable to seek re-election.

After a contentious and ch ...

, Goebel divided his party with his political tactics to win the nomination for governorship at a time when Kentucky Republicans were gaining strength, having elected the party's first governor four years previously. These dynamics led to a close contest between Goebel and William S. Taylor. In the politically chaotic climate that resulted, Goebel won the election, but was assassinated and died three days in office. Everyone charged in connection with the murder was either acquitted or eventually pardoned, and the identity of his assassin remains unknown.

Early life

Heritage and career

Wilhelm Justus Goebel was born January 4, 1856, in eitherSullivan County, Pennsylvania

Sullivan County is a county in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. It is part of Northeastern Pennsylvania. As of the 2020 census, the population was 5,840, making it the second-least populous county in Pennsylvania. Its county seat is Laporte ...

, or Albany Township, Bradford County, Pennsylvania

Albany Township is a township in Bradford County, Pennsylvania. It is part of Northeastern Pennsylvania. The population was 860 at the 2020 census.

Geography

Albany Township is located in southern Bradford County, along the Sullivan County li ...

, to Wilhelm and Augusta Goebel (), immigrants from Hanover

Hanover (; german: Hannover ; nds, Hannober) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Lower Saxony. Its 535,932 (2021) inhabitants make it the 13th-largest city in Germany as well as the fourth-largest city in Northern Germany ...

, Germany. The eldest of the four children, he was born two months premature and weighed less than . His father served as a private in Company B, 82nd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

, and Goebel's mother raised her children alone, teaching them much about their German heritage. Wilhelm spoke German until the age of six, but he embraced American culture, adopting the English spelling of his name as "William".

After being discharged from the army in 1863, Goebel's father moved his family to Covington, Kentucky

Covington is a home rule-class city in Kenton County, Kentucky, United States, located at the confluence of the Ohio and Licking Rivers. Cincinnati, Ohio, lies to its immediate north across the Ohio and Newport, to its east across the Licking ...

. Goebel attended school in Covington and was then apprenticed to a jeweler in Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line w ...

, Ohio. After a brief time at Hollingsworth Business College in mid 1870s, he became an apprentice in the law firm of John W. Stevenson, who had served as governor of Kentucky from 1867 to 1871. Goebel eventually became Stevenson's partner and executor of his estate. Goebel graduated from Cincinnati Law School

The University of Cincinnati College of Law was founded in 1833 as the Cincinnati Law School. It is the fourth oldest continuously running law school in the United States — after Harvard, the University of Virginia, and Yale — and the first in ...

in 1877, and enrolled at the Kenyon College

Kenyon College is a private liberal arts college in Gambier, Ohio. It was founded in 1824 by Philander Chase. Kenyon College is accredited by the Higher Learning Commission.

Kenyon has 1,708 undergraduates enrolled. Its 1,000-acre campus is s ...

in Gambier, Ohio

Gambier is a village in Knox County, Ohio, United States. The population was 2,391 at the 2010 census.

Gambier is the home of Kenyon College. A major feature is a gravel path running the length of the village, referred to as "Middle Path". This ...

, before joining the practice of Kentucky state representative John G. Carlisle

John Griffin Carlisle (September 5, 1834July 31, 1910) was an American politician from the commonwealth of Kentucky and was a member of the Democratic Party. He was elected to the United States House of Representatives seven times, first in ...

. He then rejoined Stevenson in Covington in 1883, after the death of Stevenson's previous partner.

Personal characteristics

According to authorJames C. Klotter

James C. Klotter is an American historian who has served as the State Historian of Kentucky since 1980. Klotter is also a history professor at Georgetown College

Georgetown College is a private Christian college in Georgetown, Kentucky. Charte ...

, Goebel was not known as a particularly genial person in public. He belonged to few social organizations and greeted none but his closest friends with a smile or handshake. He was rarely linked romantically with a woman and was the only governor of Kentucky who never married. Journalist Irvin S. Cobb

Irvin Shrewsbury Cobb (June 23, 1876 – March 11, 1944) was an American author, humorist, editor and columnist from Paducah, Kentucky, who relocated to New York in 1904, living there for the remainder of his life. He wrote for the ''New York Worl ...

remarked, "I never saw a man who, physically, so closely suggested the reptilian as this man did." Others commented on his "contemptuous" lips, "sharp" nose, and "humorless" eyes. Goebel was not a gifted public speaker, often eschewing flowery imagery and relying on his deep, powerful voice and forceful delivery to drive home his points. Klotter wrote, "When coupled to somewhat demagogic appeals and to an occasional phrase that stirred emotions, this delivery made for an effective speech, but never more than an average one." While lacking in the social qualities common to politicians, one characteristic that served Goebel well in the political arena was his intellect. Goebel was well-read, and supporters and opponents both conceded that his mental prowess was impressive. Cobb concluded that he had never been more impressed with a man's intellect than he had been with Goebel's.

Political career

Kentucky Senate

In 1887, James William Bryan vacated his seat in the

In 1887, James William Bryan vacated his seat in the Kentucky Senate

The Kentucky Senate is the upper house of the Kentucky General Assembly. The Kentucky Senate is composed of 38 members elected from single-member districts throughout the Commonwealth. There are no term limits for Kentucky Senators. The Kentu ...

to pursue the office of lieutenant governor

A lieutenant governor, lieutenant-governor, or vice governor is a high officer of state, whose precise role and rank vary by jurisdiction. Often a lieutenant governor is the deputy, or lieutenant, to or ranked under a governor — a "second-in-comm ...

. Goebel decided to seek election to the vacant seat representing Covington. He campaigned on the platform of railroad regulation and labor causes. Like Stevenson, he insisted on the right of the people to control chartered corporations. The Union Labor Party had risen to power in the area with a platform similar to Goebel's. However, while Goebel had to stick close to his allies in the Democratic Party, the Union Labor Party courted the votes of both Democrats and Republicans and made the election close, which was decided in Goebel's favor by just 56 votes. During his first term as senator, the State Railroad Commission increased to over $3,000,000 tax evaluation on the property of Louisville and Nashville Railroad

The Louisville and Nashville Railroad , commonly called the L&N, was a Class I railroad that operated freight and passenger services in the southeast United States.

Chartered by the Commonwealth of Kentucky in 1850, the road grew into one of t ...

. A proposal from pro-railroad legislators in the Kentucky House of Representatives to abolish Kentucky's Railroad Commission was passed and sent to the Senate. Cassius Marcellus Clay responded by proposing a committee to investigate lobbying by the railroad industry. Goebel served on the committee, which uncovered significant violations by the railroad lobby. He also helped defeat the bill to abolish the Railroad Commission in the Senate. These actions increased his popularity and he was elected senator unopposed in 1889 for a full term. Goebel was well able to broker deals with fellow lawmakers and was equally able and willing to break the deals if a better deal came along. His tendency to use the state's political machine

In the politics of representative democracies, a political machine is a party organization that recruits its members by the use of tangible incentives (such as money or political jobs) and that is characterized by a high degree of leadership co ...

ry to advance his agenda earned him the nickname "William the Conqueror

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England, reigning from 1066 until his death in 10 ...

".

Goebel served as a delegate to Kentucky's fourth constitutional convention in 1890, which produced the current Constitution of Kentucky The Constitution of the Commonwealth of Kentucky is the document that governs the Commonwealth of Kentucky. It was first adopted in 1792 and has since been rewritten three times and amended many more. The later versions were adopted in 1799, 1850, a ...

. Despite being a delegate, Goebel showed little interest in participating in the process of creating a new Constitution. The convention was in session for approximately 250 days, but Goebel was present for approximately only 100 days. However, he did secure the inclusion of the Railroad Commission in the new Constitution. As a Constitutional entity, the Commission could only be abolished by an amendment ratified by a popular vote. This effectively protected the Commission from ever being unilaterally dismantled by the General Assembly

A general assembly or general meeting is a meeting of all the members of an organization or shareholders of a company.

Specific examples of general assembly include:

Churches

* General Assembly (presbyterian church), the highest court of pres ...

. Klotter wrote, "Goebel used the constitution as a vehicle to enact laws which he had not been able to pass in the more conservative legislature." Goebel won another term in 1893 by a three-to-one margin over his Republican opponent. By 1894, he had been elected as the President pro tempore of the Kentucky Senate

President Pro Tempore of the Kentucky Senate was the title of highest-ranking member of the Kentucky Senate prior to enactment of a 1992 amendment to the Constitution of Kentucky.

Prior to the 1992 amendment of Section 83 of the Constitution of K ...

.

Duel with John Sanford

In 1895, Goebel engaged in what many observers considered to be a

In 1895, Goebel engaged in what many observers considered to be a duel

A duel is an arranged engagement in combat between two people, with matched weapons, in accordance with agreed-upon rules.

During the 17th and 18th centuries (and earlier), duels were mostly single combats fought with swords (the rapier and ...

with John Lawrence Sanford. Sanford, a former Confederate general staff officer turned cashier, had clashed with Goebel before. Goebel's successful campaign to remove tolls from some of Kentucky's turnpikes cost Sanford a large amount of money. Many believed that Sanford had blocked Goebel's appointment to the Kentucky Court of Appeals, in retaliation. Incensed, Goebel had written an article in a local newspaper referring to Sanford as "Gonorrhea

Gonorrhea, colloquially known as the clap, is a sexually transmitted infection (STI) caused by the bacterium ''Neisseria gonorrhoeae''. Infection may involve the genitals, mouth, or rectum. Infected men may experience pain or burning with u ...

John." On April 11, 1895, Goebel and two acquaintances went to Covington to cash a check. Goebel suggested they avoid Sanford's bank, but Sanford, standing outside the bank, spoke to the men before they could cross the street to a different bank. Sanford greeted Goebel's friends, offering them his left hand. However, Goebel noticed that Sanford's right hand was on a pistol concealed in his pocket. Having come armed himself, Goebel clutched his revolver in his pocket. Sanford confronted Goebel and said, "I understand that you assume authorship of that article." "I do", replied Goebel.

The shooting took place at 1:30 p.m. According to the witnesses, both men then drew their pistols, but no one was sure which had fired first. One of the witnesses – W. J. Hendricks, the attorney general of Kentucky, said "I don't know who shot first, the shots were so close together." Another witness, Frank P. Helm, said "I was right up against them and really thought at first that I had, myself, been shot." Sanford's bullet passed through Goebel's coat and ripped his trousers, but left him uninjured. Goebel's shot fatally struck Sanford in the head; Sanford died five hours later. Goebel pled self-defense and was acquitted. The acquittal was significant because the Kentucky constitution prohibited dueling. If Goebel had been convicted of dueling, he would have been ineligible to hold any public office. The shooting made Goebel unpopular among Kentucky's Confederate veterans, who also noted his non-southern background and his father's service in the Union army.

Goebel Election Law

Kentucky Democrats, who controlled the General Assembly believed that county election commissioners had been unfair in selecting local election officials, and had contributed to the election of Republican governorWilliam O. Bradley

William O'Connell Bradley (March 18, 1847May 23, 1914) was a politician from the U.S. state of Kentucky. He served as the 32nd Governor of Kentucky and was later elected by the state legislature as a U.S. senator from that state. The first ...

in 1895. Goebel proposed a bill, known as the "Goebel Election Law", which passed along strict party lines and over Governor Bradley's veto, created a three-member state election commission, appointed by the General Assembly, to choose the county election commissioners. It allowed the Democratic-controlled General Assembly to appoint only Democrats to the election commission. Many voters decried the bill as a self-serving attempt by Goebel to increase his political power, and the election board remained a controversial issue until its abolition in a special session of the legislature in 1900. Goebel became the subject of much opposition from constituencies of both parties in Kentucky after the passage of the law.

Gubernatorial election of 1899

In 1896, whenWilliam Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running ...

electrified the Democratic National Convention

The Democratic National Convention (DNC) is a series of presidential nominating conventions held every four years since 1832 by the United States Democratic Party. They have been administered by the Democratic National Committee since the 18 ...

with his Cross of Gold speech

The Cross of Gold speech was delivered by William Jennings Bryan, a former United States Representative from Nebraska, at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago on July 9, 1896. In his address, Bryan supported " free silver" (i.e. bim ...

and won the nomination for president, many delegates from Kentucky bolted the convention. Various Kentuckian politicians believed that free silver

Free silver was a major economic policy issue in the United States in the late 19th-century. Its advocates were in favor of an expansionary monetary policy featuring the unlimited coinage of silver into money on-demand, as opposed to strict adhe ...

was a populist idea, and it did not belong to the Democratic Party. Subsequently, Republican William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in t ...

won the 1896 presidential election, carrying Kentucky. Author Nicholas C. Burckel believed that this set the stage for "horripilating gubernatorial election of 1899". Three men sought the Democratic nomination for governor at the 1899 party convention in Louisville

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border.

...

– Goebel, Parker Watkins Hardin

Parker Watkins ("Wat") Hardin (June 3, 1841 – July 25, 1920) was a politician from the U.S. state of Kentucky. From 1879 to 1888, he served as Attorney General of Kentucky. He was an unsuccessful candidate for Governor of Kentucky in 1891, 1895 ...

, and William Johnson Stone. When Hardin appeared to be the front-runner for the nomination, Stone and Goebel agreed to work together against him. They concluded that Stone's supporters would endorse whomever Goebel picked to preside over the convention. In exchange, half the delegates from Louisville, who were pledged to Goebel, would vote to nominate Stone. Goebel would then drop out of the race, but would name many of the other officials on the ticket. Both men agreed that, should one of them be defeated or withdraw from the race, they would encourage their delegates to vote for the other rather than support Hardin. As word of the plan spread, Hardin dropped out of the race, believing he would be beaten by the Stone–Goebel alliance. When the convention convened on June 24, several chaotic ballots resulted in no clear majority for anyone, and Goebel's hand-picked chairman announced the man with the lowest vote total in the next canvass would be dropped, which turned out to be Stone. This put Stone's supporters in a difficult position, and were forced to choose between Hardin, who was seen as a pawn of the railroads, or Goebel. Enough of them sided with Goebel to give him the nomination. Goebel's tactics, while not illegal, were unpopular and divided the party. A disgruntled faction calling themselves the "Honest Election Democrats" held a separate convention in Lexington

Lexington may refer to:

Places England

* Laxton, Nottinghamshire, formerly Lexington

Canada

* Lexington, a district in Waterloo, Ontario

United States

* Lexington, Kentucky, the largest city with this name

* Lexington, Massachusetts, the oldes ...

and nominated John Y. Brown as their gubernatorial candidate.

Republican William S. Taylor defeated both Democratic candidates in the general election, but his margin over Goebel was only 2,383 votes. Democrats in the General Assembly began making accusations of voting irregularities in some counties, but in a surprise decision, the Board of Elections created by the Goebel Election Law, manned by three hand-picked pro-Goebel Democrats, ruled 2–1 that the disputed ballots should count, saying the law gave them no legal power to reverse the official county results and that under the Kentucky Constitution the power to review the election lay in the General Assembly. The Assembly then invalidated enough Republican ballots to give the election to Goebel. The Assembly's Republican minority was incensed, as were voters in traditionally Republican districts. For several days, the state hovered on the brink of a possible civil war.

Assassination and legacy

Shooting and death

The election results still being in dispute, Goebel was warned of a rumored assassination plot against him. Nevertheless, flanked by two bodyguards, Goebel walked to the Old State Capitol on the morning of January 30, 1900. Conflicting reports describe what happened next, but either five or six shots were fired from the nearby State Building, one striking Goebel in the chest, seriously wounding him. Taylor, serving as Governor pending a final decision on the election, called out themilitia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

and ordered the General Assembly into a special session in London, Kentucky

London is a home rule-class city in Laurel County, Kentucky, in the United States. It is the seat of its county. The population was 7,993 at the time of the 2010 census. It is the second-largest city named "London" in the United States and the ...

– a Republican area. The Republican minority obeyed the call, and went to London. Democrats resisted the move, many going instead to Louisville

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border.

...

. Both groups claimed authority, but the Republicans were too few to muster a quorum

A quorum is the minimum number of members of a deliberative assembly (a body that uses parliamentary procedure, such as a legislature) necessary to conduct the business of that group. According to '' Robert's Rules of Order Newly Revised'', the ...

. That evening, the day after being shot, Goebel was sworn in as Governor. In his only official act, Goebel signed a proclamation to dissolve the militia called up by Taylor, which was ignored by the militia's Republican commander. Despite the care of 18 physicians, Goebel died the afternoon of February 3, 1900. Journalists recalled his last words

Last words are the final utterances before death. The meaning is sometimes expanded to somewhat earlier utterances.

Last words of famous or infamous people are sometimes recorded (although not always accurately) which became a historical and liter ...

as "Tell my friends to be brave, fearless, and loyal to the common people." Skeptic Irvin S. Cobb

Irvin Shrewsbury Cobb (June 23, 1876 – March 11, 1944) was an American author, humorist, editor and columnist from Paducah, Kentucky, who relocated to New York in 1904, living there for the remainder of his life. He wrote for the ''New York Worl ...

uncovered another story from some in the room at the time. On having eaten his last meal, the governor supposedly remarked "Doc, that was a damned bad oyster." Goebel remains the only American governor ever assassinated while in office. In respect of Goebel's displeasure with the Louisville and Nashville Railroad, his body was transported not by the L&N direct line, but circuitously from his hometown of Covington north across the Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of ...

to Cincinnati, and then south to Frankfort on the Queen and Crescent Railroad.

Amid the controversy that had resulted in Goebel's assassination, the Kentucky Court of Appeals ruled that the General Assembly had acted legally in declaring Goebel the winner of the election. That decision was appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. Federal tribunals in the United States, federal court cases, and over Stat ...

. Arguments were presented in the case '' Taylor v. Beckham'' on April 30, 1900, but on May 21, the justices decided 8–1 not to hear the case, allowing the Court of Appeals' decision to stand. Goebel's lieutenant governor

A lieutenant governor, lieutenant-governor, or vice governor is a high officer of state, whose precise role and rank vary by jurisdiction. Often a lieutenant governor is the deputy, or lieutenant, to or ranked under a governor — a "second-in-comm ...

J. C. W. Beckham ascended to the governorship.

Trials, investigations, and legacy

During the ensuing investigation of Goebel's assassination, suspicion naturally fell on deposed Governor Taylor, who had promptly fled toIndianapolis

Indianapolis (), colloquially known as Indy, is the state capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the seat of Marion County. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the consolidated population of Indianapolis and Marion ...

, under the looming threat of indictment. The governor of Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th ...

refused to extradite Taylor, and thus he was never questioned about his knowledge of the plot to kill Goebel. Ultimately, in 1909, Taylor was pardoned by Beckham's successor, Republican governor Augustus E. Willson. However, a total of sixteen people, including Taylor, would be indicted in connection with Goebel's assassination. Three accepted immunity from prosecution in exchange for testimony. Only five ever went to trial, two of those being acquitted. Convictions were handed down against Taylor's Secretary of State Caleb Powers

Caleb Powers (February 1, 1869 – July 25, 1932) was a United States representative from Kentucky and the first Secretary of State of Kentucky convicted as an accessory to murder.

Early life

He was born near Williamsburg, Kentucky. He attended ...

, Henry Youtsey, and Jim Howard. The prosecution charged that Powers was the mastermind, having a political opponent killed so that Taylor could stay in office. Youtsey was an alleged intermediary, and Howard, who was said to have been in Frankfort to seek a pardon from Taylor for the killing of a man in a family feud, was accused of being the actual assassin. Republican appeal courts overturned Powers' and Howard's convictions, though Powers was tried three more times, resulting in two convictions and a hung jury

A hung jury, also called a deadlocked jury, is a judicial jury that cannot agree upon a verdict after extended deliberation and is unable to reach the required unanimity or supermajority. Hung jury usually results in the case being tried again.

T ...

, and Howard was tried and convicted twice more. Both men were pardoned in 1908 by Willson. Youtsey, who was sentenced to life imprisonment

Life imprisonment is any sentence of imprisonment for a crime under which convicted people are to remain in prison for the rest of their natural lives or indefinitely until pardoned, paroled, or otherwise commuted to a fixed term. Crimes fo ...

, did not appeal, but after two years in prison, he turned state's evidence

A criminal turns state's evidence by admitting guilt and testifying as a witness for the state against their associate(s) or accomplice(s), often in exchange for leniency in sentencing or immunity from prosecution.Howard Abadinsky, ''Organized C ...

. In Howard's second trial, Youtsey claimed that Taylor had discussed an assassination plot with Youtsey and Howard. He backed the prosecution's claims that Taylor and Powers worked out the details; he had acted as an intermediary, and Howard fired the shot. However, on cross-examination, the defense pointed out contradictions in the details of Youtsey's story, but Howard was still convicted. Youtsey was parole

Parole (also known as provisional release or supervised release) is a form of early release of a prison inmate where the prisoner agrees to abide by certain behavioral conditions, including checking-in with their designated parole officers, or ...

d in 1916 and was pardoned in 1919 by Democratic governor James D. Black. Of those allegedly involved in the killing: Taylor died in 1928; Powers died in 1932; Youtsey died in 1942. Most historians agree that the identity of the assassin of Goebel is unclear. Goebel Avenue in Elkton, Kentucky, and Goebel Park in Covington, Kentucky

Covington is a home rule-class city in Kenton County, Kentucky, United States, located at the confluence of the Ohio and Licking Rivers. Cincinnati, Ohio, lies to its immediate north across the Ohio and Newport, to its east across the Licking ...

are named in Goebel's honor.

See also

*History of Kentucky

The prehistory and history of Kentucky span thousands of years, and have been influenced by the state's diverse geography and central location. Based on evidence in other regions, it is likely that the human history of Kentucky began sometime b ...

* List of assassinated American politicians

* List of unsolved murders

These lists of unsolved murders include notable cases where victims were murdered in unknown circumstances.

* List of unsolved murders (before 1900)

* List of unsolved murders (1900–1979)

* List of unsolved murders (1980–1999)

* List of u ...

Notes

References

Works cited

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

*External links

, - {{DEFAULTSORT:Goebel, William 1856 births 1900 deaths 1900 murders in the United States 19th-century American politicians American duellists American people of German descent Assassinated American politicians Burials at Frankfort Cemetery Deaths by firearm in Kentucky Democratic Party governors of Kentucky Democratic Party Kentucky state senators Kenyon College alumni Male murder victims People from Carbondale, Pennsylvania People murdered in Kentucky Populism in the United States University of Cincinnati alumni Unsolved murders in the United States