William E. Borah on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

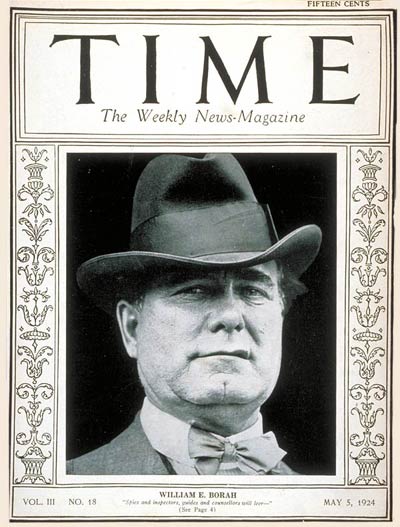

William Edgar Borah (June 29, 1865 – January 19, 1940) was an outspoken Republican

Republicans felt Wilson was making a political issue of the peace, especially when the president urged a Democratic Congress prior to the 1918 election, and attended the Paris Peace Conference in person, taking no Republicans on his delegation. Wilson had felt his statement was the only chance of getting a Senate that might ratify a treaty for a postwar organization to keep the peace, and deemed conciliation pointless. In Paris, Wilson and other leaders negotiated what would become the

Republicans felt Wilson was making a political issue of the peace, especially when the president urged a Democratic Congress prior to the 1918 election, and attended the Paris Peace Conference in person, taking no Republicans on his delegation. Wilson had felt his statement was the only chance of getting a Senate that might ratify a treaty for a postwar organization to keep the peace, and deemed conciliation pointless. In Paris, Wilson and other leaders negotiated what would become the  The small Republican majority in the Senate made Irreconcilable votes necessary to Lodge's strategy, and he met with Borah in April 1919, persuading him to go along with the plan of delay and reservations as the most likely to succeed, as it would allow the initial popular support for Wilson's proposal to diminish. Neither senator really liked or trusted the other, but they formed a wary pact to defeat the treaty. Lodge was also chairman of the

The small Republican majority in the Senate made Irreconcilable votes necessary to Lodge's strategy, and he met with Borah in April 1919, persuading him to go along with the plan of delay and reservations as the most likely to succeed, as it would allow the initial popular support for Wilson's proposal to diminish. Neither senator really liked or trusted the other, but they formed a wary pact to defeat the treaty. Lodge was also chairman of the

Harding's death in August 1923 brought Calvin Coolidge to the White House. Borah had been dismayed by Harding's conservative views, and believed Coolidge had shown liberal tendencies as a governor. He met with Coolidge multiple times in late 1923, and found the new president interested in his ideas on policies foreign and domestic. Borah was encouraged when Coolidge included in his annual message to Congress a suggestion that he might open talks with the Soviet Union on trade—the Bolshevik government had not been recognized since the 1917

Harding's death in August 1923 brought Calvin Coolidge to the White House. Borah had been dismayed by Harding's conservative views, and believed Coolidge had shown liberal tendencies as a governor. He met with Coolidge multiple times in late 1923, and found the new president interested in his ideas on policies foreign and domestic. Borah was encouraged when Coolidge included in his annual message to Congress a suggestion that he might open talks with the Soviet Union on trade—the Bolshevik government had not been recognized since the 1917

Borah was not personally harmed by the stock market crash of October 1929, having sold any stocks and invested in government bonds. Thousands of Americans had borrowed on margin, and were ruined by the crash. Congress in June 1930 passed the Hawley–Smoot Tariff, sharply increasing rates on imports. Borah was one of 12 Republicans who joined Democrats in opposing the bill, which passed the Senate 44–42. Borah was up for election in 1930, and despite a minimal campaign effort, took over 70 percent of the vote in a bad year for Republicans. When he returned to Washington for the

Borah was not personally harmed by the stock market crash of October 1929, having sold any stocks and invested in government bonds. Thousands of Americans had borrowed on margin, and were ruined by the crash. Congress in June 1930 passed the Hawley–Smoot Tariff, sharply increasing rates on imports. Borah was one of 12 Republicans who joined Democrats in opposing the bill, which passed the Senate 44–42. Borah was up for election in 1930, and despite a minimal campaign effort, took over 70 percent of the vote in a bad year for Republicans. When he returned to Washington for the

Borah ran for the Republican nomination for president in 1936, the first from Idaho to do so. His candidacy was opposed by the conservative Republican leadership. Borah praised Roosevelt for some of his policies, and deeply criticized the Republican Party. With only 25 Republicans left in the Senate, Borah saw an opportunity to recast the Republican Party along progressive lines, as he had long sought to do. He was opposed by the Republican organization, which sought to dilute his strength in the primaries by running state

Borah ran for the Republican nomination for president in 1936, the first from Idaho to do so. His candidacy was opposed by the conservative Republican leadership. Borah praised Roosevelt for some of his policies, and deeply criticized the Republican Party. With only 25 Republicans left in the Senate, Borah saw an opportunity to recast the Republican Party along progressive lines, as he had long sought to do. He was opposed by the Republican organization, which sought to dilute his strength in the primaries by running state  Only sixteen Republicans remained in the Senate, most progressives, when Congress met in January 1937, but Borah retained much influence as he was liked and respected by Democrats. Many of Roosevelt's

Only sixteen Republicans remained in the Senate, most progressives, when Congress met in January 1937, but Borah retained much influence as he was liked and respected by Democrats. Many of Roosevelt's

In 1895, Borah married Mary McConnell of

In 1895, Borah married Mary McConnell of

Borah's effectiveness as a reformer was undercut by his tendency to abandon causes after initial enthusiasm, as Maddox put it, "although he was very skilled at speaking out, his unwillingness to do more than protest eventually earned him a reputation for futility."

Borah's effectiveness as a reformer was undercut by his tendency to abandon causes after initial enthusiasm, as Maddox put it, "although he was very skilled at speaking out, his unwillingness to do more than protest eventually earned him a reputation for futility."

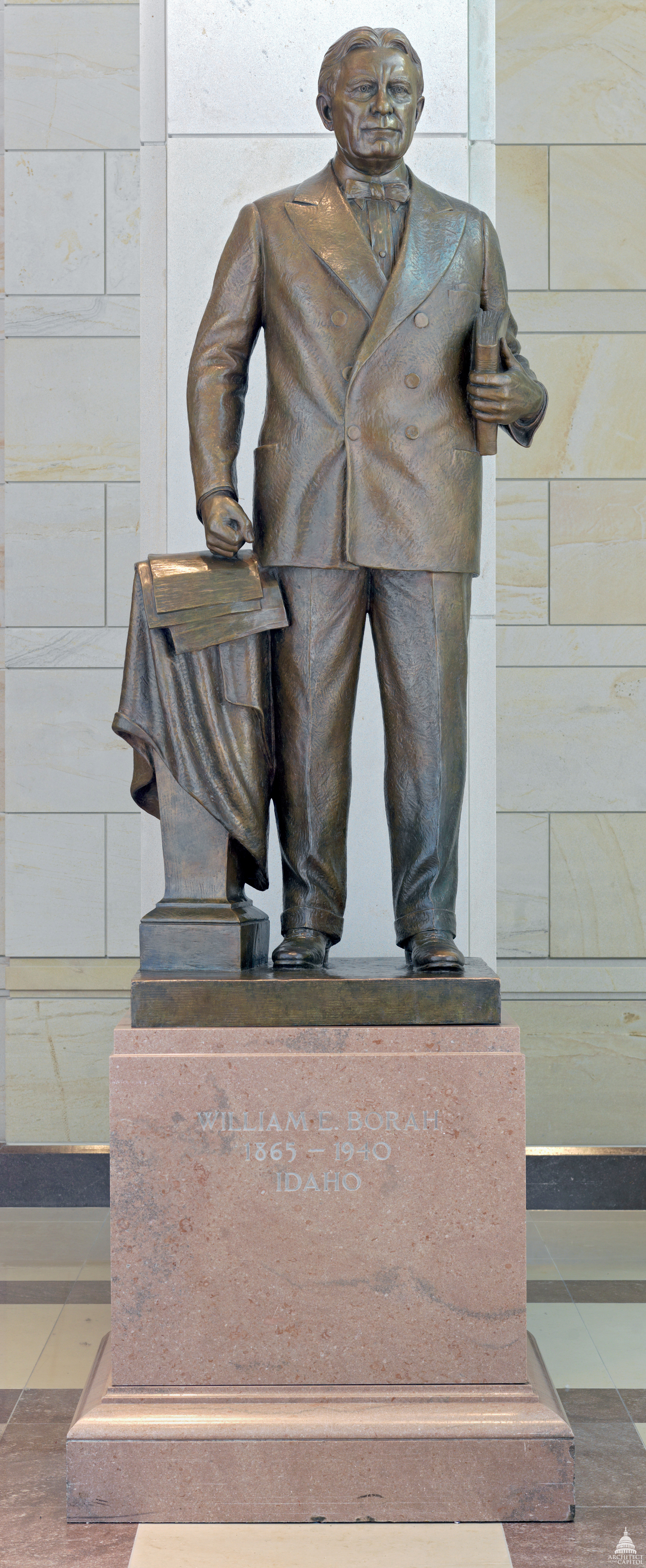

National Statutory Hall

– U.S. Capitol

Biography UMKC Law School

– biography of William Borah

History News Network

– The West: "The Lion of Idaho" ... William E. Borah, More Than a "Little American"

* , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Borah, William Edgar 1865 births 1940 deaths 20th-century American politicians American people of German descent American Protestants Idaho lawyers Idaho Republicans People from Boise, Idaho People from Lyons, Kansas People from Wayne County, Illinois Republican Party United States senators from Idaho Sheep Wars Candidates in the 1916 United States presidential election Candidates in the 1920 United States presidential election Candidates in the 1936 United States presidential election American lawyers admitted to the practice of law by reading law Chairmen of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations Non-interventionism

United States Senator

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and power ...

, one of the best-known figures in Idaho's history. A progressive

Progressive may refer to:

Politics

* Progressivism, a political philosophy in support of social reform

** Progressivism in the United States, the political philosophy in the American context

* Progressive realism, an American foreign policy pa ...

who served from 1907 until his death in 1940, Borah is often considered an isolationist

Isolationism is a political philosophy advocating a national foreign policy that opposes involvement in the political affairs, and especially the wars, of other countries. Thus, isolationism fundamentally advocates neutrality and opposes entangl ...

, because he led the Irreconcilables

{{for, Irreconcilables during the Philippine–American War , Irreconcilables (Philippines)

The Irreconcilables were bitter opponents of the Treaty of Versailles in the United States in 1919. Specifically, the term refers to about 12 to 18 United ...

, senators who would not accept the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

, Senate ratification

Ratification is a principal's approval of an act of its agent that lacked the authority to bind the principal legally. Ratification defines the international act in which a state indicates its consent to be bound to a treaty if the parties inten ...

of which would have made the U.S. part of the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

.

Borah was born in rural Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rockfo ...

to a large farming family. He studied at the University of Kansas

The University of Kansas (KU) is a public research university with its main campus in Lawrence, Kansas, United States, and several satellite campuses, research and educational centers, medical centers, and classes across the state of Kansas. Tw ...

and became a lawyer in that state before seeking greater opportunities in Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the Canada–United States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Montana and Wyomi ...

. He quickly rose in the law and in state politics, and after a failed run for the House of Representatives in 1896 and one for the United States Senate in 1903, was elected to the Senate in 1907. Before he took his seat in December of that year, he was involved in two prominent legal cases. One, the murder conspiracy trial of Big Bill Haywood

William Dudley "Big Bill" Haywood (February 4, 1869 – May 18, 1928) was an American labor organizer and founding member and leader of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and a member of the executive committee of the Socialist Party of A ...

, gained Borah fame though Haywood was found not guilty and the other, a prosecution of Borah for land fraud, made him appear a victim of political malice even before his acquittal.

In the Senate, Borah became one of the progressive insurgents who challenged President William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

's policies, though Borah refused to support former president Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

's third-party bid against Taft in 1912. Borah reluctantly voted for war in 1917 and, once it concluded, he fought against the Versailles treaty, and the Senate did not ratify it. Remaining a maverick, Borah often fought with the Republican presidents in office between 1921 and 1933, though Calvin Coolidge offered to make Borah his running mate in 1924. Borah campaigned for Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party, holding office during the onset of the Gre ...

in 1928, something he rarely did for presidential candidates and never did again.

Deprived of his post as Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee

The United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations is a standing committee of the U.S. Senate charged with leading foreign-policy legislation and debate in the Senate. It is generally responsible for overseeing and funding foreign aid pro ...

when the Democrats took control of the Senate in 1933, Borah agreed with some of the New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Cons ...

legislation, but opposed other proposals. He ran for the Republican nomination for president in 1936, but party regulars were not inclined to allow a longtime maverick to head the ticket. In his final years, he felt he might be able to settle differences in Europe by meeting with Hitler; though he did not go, this has not enhanced his historical reputation. Borah died in 1940; his statue, presented by the state of Idaho in 1947, stands in the National Statuary Hall Collection

The National Statuary Hall Collection in the United States Capitol is composed of statues donated by individual states to honor persons notable in their history. Limited to two statues per state, the collection was originally set up in the old ...

.

Childhood and early career

William Edgar Borah was born in Jasper Township, Illinois, near Fairfield in Wayne County. His parents were farmers Elizabeth (West) and William Nathan Borah. Borah was distantly related toKatharina von Bora

Katharina von Bora (; 29 January 1499 – 20 December 1552), after her wedding Katharina Luther, also referred to as "die Lutherin" ("the Lutheress"), was the wife of Martin Luther, German reformer and a seminal figure of the Protestant Reform ...

, the Catholic nun who left her convent in the 16th century and married reformer Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Lutheranis ...

. His Borah ancestors came to America in about 1760, fought in the Revolutionary War, and moved west with the frontier. The young William E. Borah was the seventh of ten children, and the third son.

Although Borah was not a good student, at an early age he began to love oratory and the written word. Borah was educated at Tom's Prairie School, near Fairfield. When Borah exhausted its rudimentary resources, his father sent him in 1881 to Southern Illinois Academy, a Cumberland Presbyterian

The Cumberland Presbyterian Church is a Presbyterian denomination spawned by the Second Great Awakening. Matthew H. Gore, The History of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church in Kentucky to 1988, (Memphis, Tennessee: Joint Heritage Committee, 2000). ...

academy at Enfield, to train for the ministry. The 63 students there included two future U.S. senators, Borah and Wesley Jones, who would represent the state of Washington; the two often debated as schoolboys. Instead of becoming a preacher, Borah was in 1882 expelled for hitching rides on the Illinois Central

The Illinois Central Railroad , sometimes called the Main Line of Mid-America, was a railroad in the Central United States, with its primary routes connecting Chicago, Illinois, with New Orleans, Louisiana, and Mobile, Alabama. A line also co ...

to spend the night in the town of Carmi.

He ran away from home with an itinerant Shakespearean company, but his father persuaded him to return. In his late teenage years, he became interested in the law, and later stated, "I can't remember when I didn't want to be a lawyer ... there is no other profession where one can be absolutely independent".

With his father finally accepting his ambition to be a lawyer rather than a clergyman, Borah in 1883 went to live with his sister Sue in Lyons, Kansas

Lyons is a city in and the county seat of Rice County, Kansas, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 3,611.

History

For millennia, the land now known as Kansas was inhabited by Native Americans.

Although Cor ...

; her husband, Ansel M. Lasley, was an attorney. Borah initially worked as a teacher, but became so engrossed in historical topics at the town library that he was ill-prepared for class; he and the school parted ways. In 1885 Borah enrolled at the University of Kansas

The University of Kansas (KU) is a public research university with its main campus in Lawrence, Kansas, United States, and several satellite campuses, research and educational centers, medical centers, and classes across the state of Kansas. Tw ...

, and rented an inexpensive room in a professor's home in Lawrence; he studied alongside students who would become prominent, such as William Allen White

William Allen White (February 10, 1868 – January 29, 1944) was an American newspaper editor, politician, author, and leader of the Progressive movement. Between 1896 and his death, White became a spokesman for middle America.

At a 1937 ...

and Fred Funston. Borah was working his way through college, but his plans were scuttled when he contracted tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in w ...

in early 1887. He had to return to Lyons, where his sister nursed him to health, and he began to read law

Reading law was the method used in common law countries, particularly the United States, for people to prepare for and enter the legal profession before the advent of law schools. It consisted of an extended internship or apprenticeship under the ...

under his brother-in-law Lasley's supervision. Borah passed the bar examination in September 1887, and went into partnership with his brother-in-law.

The mayor of Lyons appointed Borah as city attorney in 1889, but the young lawyer felt that he was destined for bigger things than a small Kansas town suffering in the hard times that persisted on the prairie in the late 1880s and early 1890s. Following the advice attributed to Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley (February 3, 1811 – November 29, 1872) was an American newspaper editor and publisher who was the founder and editor of the ''New-York Tribune''. Long active in politics, he served briefly as a congressman from New York, ...

, Borah chose to go west and grow up with the country. In October 1890, uncertain of his destination, he boarded the Union Pacific Railroad

The Union Pacific Railroad , legally Union Pacific Railroad Company and often called simply Union Pacific, is a freight-hauling railroad that operates 8,300 locomotives over routes in 23 U.S. states west of Chicago and New Orleans. Union Pac ...

in Omaha

Omaha ( ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Nebraska and the county seat of Douglas County. Omaha is in the Midwestern United States on the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's 39th-largest cit ...

. On the advice of a gambler on board the train, Borah decided to settle in Boise, Idaho

Boise (, , ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Idaho and is the county seat of Ada County. On the Boise River in southwestern Idaho, it is east of the Oregon border and north of the Nevada border. The downtown area ...

. His biographer, Marian C. McKenna, said that Boise was "as far west as his pocketbook would take him".

Pre-Senate career

Idaho lawyer

Idaho had been admitted to the Union earlier in 1890, and Boise, the state capital, was a boom town, where the police and courts were not yet fully effective. Borah's first case was referred to him by the gambler who had advised him on board the train; the young attorney was asked to defend a man accused of murder for shooting a Chinese immigrant in the back. Borah gained an unasked-for dismissal when the judge decided that killing a Chinese male was at worst manslaughter. Borah prospered in Boise, both in law and in politics. In 1892 he served as chair of the Republican State Central Committee. He served as political secretary to GovernorWilliam J. McConnell

William John McConnell (September 18, 1839March 30, 1925) was the third governor of Idaho from 1893 until 1897. He had previously represented the new state as one of its first United States Senators; Idaho achieved statehood in July 1890.

Early ...

. In 1895 Borah married the governor's daughter, Mary McConnell. They were married until Borah's death, but had no children together.

Idaho, a mining state, was fraught with labor tensions, and related violence was common by both employers and workers. In 1899, there was a strike, and a large group of miners dynamited facilities belonging to a mining company that refused to recognize the union. They had hijacked a train to travel to destroy the company's plant. Someone in the mob shot and killed a strikebreaker. Governor Frank Steunenberg

Frank Steunenberg (August 8, 1861December 30, 1905) was the fourth governor of the State of Idaho, serving from 1897 until 1901. He was assassinated in 1905 by one-time union member Harry Orchard, who was also a paid informant for the Cripple C ...

declared martial law and had more than one thousand miners arrested. Paul Corcoran, secretary of the union, was charged with murder. Borah was engaged as a prosecutor in a trial that began at Wallace on July 8, 1899. Prosecution witnesses testified to having seen Corcoran sitting on top of the train, rifle in hand, and later leaping to the platform. The defense contended that, given the sharp curves and rough roadbed of the rail line, no one could have sat on top of the train, nor jumped from it without severe injury. Borah took the jury to the train line and demonstrated how Corcoran could have acted. He drew on his skills as a teenage rail rider to ride the top of the train, and jump from it to the platform without injury. Corcoran was convicted, but his death sentence was commuted. He was pardoned in 1901, after Steunenberg left office. Borah gained wide acclaim for his dramatic prosecution of the case.

Senate contender

In 1896, Borah joined many Idahoans, including SenatorFred Dubois

Fred Thomas Dubois (May 29, 1851February 14, 1930) was a controversial American politician from Idaho who served two terms in the United States Senate. He was best known for his opposition to the gold standard and his efforts to disenfranchise ...

, in bolting the Republican Party to support the presidential campaign of Democrat William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running ...

—free silver

Free silver was a major economic policy issue in the United States in the late 19th-century. Its advocates were in favor of an expansionary monetary policy featuring the unlimited coinage of silver into money on-demand, as opposed to strict adhe ...

, which Bryan advocated, was extremely popular in Idaho. Borah thus became a Silver Republican

The Silver Republican Party, later known as the Lincoln Republican Party, was a United States political party from 1896 to 1901. It was so named because it split from the Republican Party by supporting free silver (effectively, expansionary moneta ...

in opposition to the campaign of the Republican presidential candidate, former Ohio governor William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in ...

. Borah ran for the House of Representatives that year, but knew that with the silver vote split between himself and a Democrat-Populist

Populism refers to a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of "the people" and often juxtapose this group against " the elite". It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term develope ...

fusion candidate, he had little chance of winning. He concentrated on making speeches aimed at gaining a legislature that would re-elect Dubois—until 1913, state legislatures chose senators. Bryan, Dubois, and Borah were all defeated.

In 1898, Borah supported the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (cloc ...

and remained loyal to the Silver Republicans. By 1900, Borah deemed the silver issue of minimal importance due to increased gold production and national prosperity,. With other former silverites, he made an unapologetic return to the Republican Party. He made speeches for McKinley, who was re-elected. Bryan, however, took Idaho's electoral votes for a second time. Dubois, though nominally remaining a Silver Republican, gained control of the state Democratic Party, and was returned to the US Senate by the Idaho Legislature

The Idaho Legislature consists of the upper Idaho Senate and the lower Idaho House of Representatives. Idaho is divided into 35 legislative districts, which each elect one senator and two representatives. There are no term limits for either ch ...

.

Borah's legal practice had made him prominent in southern Idaho, and in 1902 he sought election to the Senate. By this time, a united Republican Party was deemed likely to defeat the Democratic/Populist combine that had ruled Idaho for the past six years. The 1902 Idaho state Republican convention showed that Borah had, likely, the most support among the people, but the choice of senator was generally dictated by the caucus of the majority party in the legislature. In the 1902 election, Republicans retook control, electing a governor of their party, as well as the state's only House member and a large majority in the legislature. Three other Republicans were seeking the Senate seat, including Weldon B. Heyburn, a mining lawyer from the northern part of the state. When the legislature met in early 1903, Borah led on early caucus ballots, but then the other candidates withdrew and backed Heyburn; he was chosen by the caucus, and then by the legislature. There were many rumors of corruption in the choice of Heyburn, and Borah determined that the defeat would not end his political career. He decided to seek the seat of Senator Dubois (by then a Democrat) when it was filled by the legislature in early 1907.

At the state convention at Pocatello

Pocatello () is the county seat of and largest city in Bannock County, with a small portion on the Fort Hall Indian Reservation in neighboring Power County, in the southeastern part of the U.S. state of Idaho. It is the principal city of the ...

in 1904, Borah made a speech in support of the election of Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

for a full term as president, which was widely applauded. But the Old Guard Republicans in Idaho opposed him and they were determined to defeat Borah in his second bid for the Senate. The same year, Dubois damaged his prospects for a third term by his opposition to the appointment of H. Smith Woolley, a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, informally known as the LDS Church or Mormon Church, is a nontrinitarian Christian church that considers itself to be the restoration of the original church founded by Jesus Christ. The ch ...

(many Idahoans adhered to that faith), as assayer-in-charge of the United States Assay Office at Boise. Dubois had advanced politically through anti-Mormonism in the 1880s, but the issue was more or less dead in Idaho by 1904. Woolley was confirmed by the U.S. Senate despite Dubois's opposition, and Rufus G. Cook, in his article on the affair, suggested that Dubois was baited into acting by Borah and his supporters. The result was that Borah attacked Dubois for anti-Mormonism in both 1904 and 1906, which played well in the heavily Mormon counties in southeast Idaho.

Borah campaigned to end the caucus's role in selecting the Republican nominee for Senate, arguing that it should be decided by the people, in a convention. He drafted a resolution based on the one passed by the 1858 Illinois Republican convention that had endorsed Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

for Senate in his unsuccessful race against Stephen Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas (April 23, 1813 – June 3, 1861) was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. A senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party for president in the 1860 presidential election, which was ...

. He made a deal with a potential Republican rival, Governor Frank Gooding, whereby Borah would be nominated for Senate and Gooding for re-election and on August 1, 1906, both men received the state convention's endorsement by acclamation. Dubois was the Democratic choice, and Borah campaigned in support of President Roosevelt, argued that Republicans had brought the nation prosperity, and urged law and order

In modern politics, law and order is the approach focusing on harsher enforcement and penalties as ways to reduce crime. Penalties for perpetrators of disorder may include longer terms of imprisonment, mandatory sentencing, three-strikes laws ...

. Voters re-elected Gooding, and selected a Republican legislature, which in January 1907 retired Dubois by electing Borah to the Senate.

Haywood trial, lumber accusations

Borah presented his credentials at the Senate prior to the formal beginning of his first term on March 4, 1907. Until 1933, Congress's regular session began in December, allowing Borah time to participate in two major trials. One of these boosted him to national prominence for his role in the prosecution ofBig Bill Haywood

William Dudley "Big Bill" Haywood (February 4, 1869 – May 18, 1928) was an American labor organizer and founding member and leader of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and a member of the executive committee of the Socialist Party of A ...

, and the other, with Borah as the defendant, placed him at risk of going to prison.

Haywood was tried for conspiracy in the murder of ex-governor Steunenberg, who was assassinated on December 30, 1905 by a bomb planted on the gate at his home in Caldwell. Borah, who viewed Steunenberg as a father figure, was among the prominent Idahoans who hurried to Caldwell, and who viewed Steunenberg's shattered body and the bloodstained snow. Suspicion quickly fell on a man registered at a local hotel who proved to be Harry Orchard

Albert Edward Horsley (March 18, 1866 – April 13, 1954), best known by the pseudonym Harry Orchard, was a miner convicted of the 1905 political assassination of former Idaho Governor Frank Steunenberg. The case was one of the most sensational ...

, an explosives expert and assassin. Many labor leaders were embittered against Steunenberg for his actions while in office, and Orchard implicated four of them. The three who could be found, including Haywood, were extradited from Colorado to Idaho in February 1906. As the legal challenges wound through the courts, the case became a campaign issue both for Gooding, who had signed the extradition warrant, and for Borah, who joined the prosecution team and stated that trying the case was more important to him than being sent to the Senate.

While the Haywood defendants awaited trial, Borah and others were indicted in federal court for land fraud, having to do with the acquisition by the Barber Lumber Company (for which Borah had been counsel) of title to timber land claims. Individuals had filed for the claims, and then sold them to the Barber Company, although they had sworn that the claims were for their own use. United States Attorney

United States attorneys are officials of the U.S. Department of Justice who serve as the chief federal law enforcement officers in each of the 94 U.S. federal judicial districts. Each U.S. attorney serves as the United States' chief federal c ...

for Idaho, Norman M. Ruick, had expanded the grand jury from 12 members to 22 before he could get a majority vote to indict Borah (by a 12–10 margin). The indictment was perceived to be political, with Ruick acting on behalf of Idaho Republicans who had lost state party leadership to the new senator. Roosevelt took a wait-and-see attitude, upsetting Borah, who considered resigning his Senate seat even if exonerated.

Haywood was the first tried of the three defendants; jury selection began on May 9, 1907 and proceedings in Boise continued for over two months. The courtroom, corridors, and even the lawn outside were often filled. Counsel for the prosecution included Borah and future governor James H. Hawley; famed attorney Clarence Darrow

Clarence Seward Darrow (; April 18, 1857 – March 13, 1938) was an American lawyer who became famous in the early 20th century for his involvement in the Leopold and Loeb murder trial and the Scopes "Monkey" Trial. He was a leading member of ...

led the defense team. A highlight of the trial was Borah's cross-examination of Haywood, who denied personal animus against Steunenberg and any connection with the death. Another was Borah's final argument for the prosecution in rebuttal to Darrow on July 25 and 26.

Borah recalled the night of the ex-governor's murder:

Although Darrow won the day, gaining an acquittal for Haywood, the trial transformed Borah from an obscure freshman senator into a national figure. But Borah still had to face a jury on the land fraud charge, which he did in September 1907, a trial held then at Roosevelt's insistence—Ruick had asked for more time, but Borah wanted the matter disposed of before Congress met in December. Borah refused to challenge the indictment. At the trial, his counsel allowed Ruick free rein; the judge commented on Ruick's inability to tie Borah to any offense. The defense case consisted almost entirely of Borah's testimony, and the jury quickly acquitted him, setting off wild celebrations in Boise. Roosevelt dismissed Ruick as US Attorney in 1908.

Senator (1907–1940)

Progressive insurgent (1907–1913)

When Borah went to Washington for the Senate's regular session in December 1907, he was immediately a figure of note, not only for the dramatic events in Idaho but for keeping his Western habits, including wearing aten-gallon hat

The cowboy hat is a high-crowned, wide-brimmed hat best known as the defining piece of attire for the North American cowboy. Today it is worn by many people, and is particularly associated with ranch workers in the western and southern United ...

. It was customary then for junior senators to wait perhaps a year before giving their maiden speech

A maiden speech is the first speech given by a newly elected or appointed member of a legislature or parliament.

Traditions surrounding maiden speeches vary from country to country. In many Westminster system governments, there is a convention th ...

, but at Roosevelt's request, in April 1908, Borah spoke in defense of the president's dismissal of more than 200 African-American soldiers in the Brownsville Affair in Texas. The cause of their innocence had been pressed by the fiery Ohio senator, Joseph B. Foraker. The soldiers were accused of having shot up a Texas town near their military camp. Borah said that their alleged actions were as wrongful as the murder of Steunenberg. The accusations were later re-investigated. The government concluded that the soldiers had been accused because of racist officials in the town and, in 1972, long after the deaths of Roosevelt, Borah, and most of the soldiers, their dishonorable discharges from the military were reversed.

Republican leaders had heard that Borah was an attorney for corporations, who had prosecuted labor leaders; they believed him sympathetic to their Old Guard positions and assigned him to important committees. Borah believed in the rights of unions, so long as they did not commit violent acts. When Borah staked out progressive

Progressive may refer to:

Politics

* Progressivism, a political philosophy in support of social reform

** Progressivism in the United States, the political philosophy in the American context

* Progressive realism, an American foreign policy pa ...

positions after his swearing-in, Rhode Island Senator Nelson Aldrich

Nelson Wilmarth Aldrich (/ ˈɑldɹɪt͡ʃ/; November 6, 1841 – April 16, 1915) was a prominent American politician and a leader of the Republican Party in the United States Senate, where he represented Rhode Island from 1881 to 1911. By the ...

, the powerful chairman of the Senate Finance Committee

The United States Senate Committee on Finance (or, less formally, Senate Finance Committee) is a standing committee of the United States Senate. The Committee concerns itself with matters relating to taxation and other revenue measures generall ...

, hoped to put pressure on him through the Westerner's corporate clients, only to find that he had given up those representations before coming to Washington. Borah became one of a growing number of progressive Republicans in the Senate. Yet, Borah often opposed liberal legislation, finding fault with it or fearing it would increase the power of the federal government. Throughout his years in the Senate, in which he would serve until his death in 1940, his idiosyncratic positions would limit his effectiveness as a reformer.

After Roosevelt's hand-picked successor as president, former Secretary of War William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

, was inaugurated in March 1909, Congress battled over what became the Payne–Aldrich Tariff. At the time, tariffs were the main source of government revenue, and conflicts over them were passionate. The party platform had promised tariff reform, which progressive insurgents like Borah took to mean tariff reductions. Old Guard legislators like Senator Aldrich disagreed, and the final version actually raised rates by about one percent. The battles alienated Borah from Taft, who in a speech at Winona, Minnesota

Winona is a city in and the county seat of Winona County, in the state of Minnesota. Located in bluff country on the Mississippi River, its most noticeable physical landmark is Sugar Loaf. The city is named after legendary figure Winona, who ...

described the new law as the best tariff the country had ever had. Borah and other progressives had proposed an income tax to be attached to the tariff bill; when this was unacceptable to Taft, who feared the Supreme Court would strike it down again, Borah repackaged it as a constitutional amendment, which passed the Senate unanimously and then the House, and to the surprise of many, passed the requisite number of state legislatures by 1913 to become the Sixteenth Amendment.

Borah also had a hand in the other constitutional amendment to be ratified in 1913, the Seventeenth Amendment, providing for the direct election of senators by the people. In 1909, due to Borah's influence, the Idaho Legislature passed an act for a statewide election for US senators, with legislators in theory bound to choose the winner. By 1912 over 30 states had similar laws. Borah promoted the amendment in the Senate in 1911 and 1912 until it passed Congress and, after a year, it was ratified by the states. With the power to elect senators having passed to the people, according to McKenna, the popular Borah "secured for himself a life option on a seat in the Senate".

Borah opposed Taft over a number of issues and in March 1912 announced his support of the candidacy of Roosevelt over Taft for the Republican presidential nomination. Most delegates to the 1912 Republican National Convention

The 1912 Republican National Convention was held at the Chicago Coliseum, Chicago, Illinois, from June 18 to June 22, 1912. The party nominated President William H. Taft and Vice President James S. Sherman for re-election for the 1912 United ...

in Chicago selected by primary supported Roosevelt, but as most states held conventions to select delegates, Taft's control of the party machinery gave him the advantage. A number of states, especially in the South, had contested delegate seats, matters which would be initially settled by the Republican National Committee

The Republican National Committee (RNC) is a U.S. political committee that assists the Republican Party of the United States. It is responsible for developing and promoting the Republican brand and political platform, as well as assisting in fu ...

. Borah was Idaho's Republican National Committeeman and was one of those designated by the Roosevelt campaign to fight for it on the RNC. As Taft controlled the committee, Borah found few victories. Borah was among those who tried to find a compromise candidate, and was spoken of for that role, but all such efforts failed.

When it became clear Taft would be renominated, Roosevelt and his supporters bolted the party; the former president asked Borah to chair the organizational meeting of his new Progressive Party, but the Idahoan refused. Borah would not countenance leaving the Republican Party and did not support any of the presidential candidates (the Democrats nominated New Jersey Governor Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

). When Roosevelt came to Boise on a campaign swing in October, Borah felt he had to greet the former president and sit on the platform as Roosevelt spoke, though he was unwilling to endorse him. Roosevelt told in his speech of a long list of state delegate votes he said had been stolen from him, and after each, turned to Borah and asked, "Isn't that so, Senator Borah?" giving him no choice but to nod. It is not clear whether Borah voted for Roosevelt or Taft, he later stated both at different times. The main issue in Idaho was Borah's re-election, which was so popular that those disgruntled at the senator for not supporting Taft or Roosevelt kept quiet. Idahoans helped elect Wilson, but sent 80 Republican legislators out of 86 to Boise (with two of the six Democrats pledged to support Borah if necessary), who on January 14, 1913 returned William Borah for a second term.

Wilson years

Prewar (1913–1917)

The Republicans both lost the presidency with Wilson's inauguration and went into the minority in the Senate. In the reshuffle of committee assignments that followed, Borah was given a seat onForeign Relations

A state's foreign policy or external policy (as opposed to internal or domestic policy) is its objectives and activities in relation to its interactions with other states, unions, and other political entities, whether bilaterally or through mu ...

. He would occupy it for the next quarter century, becoming one of America's leading figures on international affairs.

Borah generally approved of many of Wilson's proposals, but found reasons to vote against them. He voted against the Federal Reserve Act

The Federal Reserve Act was passed by the 63rd United States Congress and signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson on December 23, 1913. The law created the Federal Reserve System, the central banking system of the United States.

The Panic ...

of 1913 (believing it was a handout to the rich), after gaining a concession that no banker would initially be appointed to the Federal Reserve Board

The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, commonly known as the Federal Reserve Board, is the main governing body of the Federal Reserve System. It is charged with overseeing the Federal Reserve Banks and with helping implement the mon ...

. Borah believed monopolies, public and private, should be broken up, and believed the new Federal Trade Commission

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is an independent agency of the United States government whose principal mission is the enforcement of civil (non-criminal) antitrust law and the promotion of consumer protection. The FTC shares jurisdiction ov ...

would prove a means for trusts

A trust is a legal relationship in which the holder of a right gives it to another person or entity who must keep and use it solely for another's benefit. In the Anglo-American common law, the party who entrusts the right is known as the " sett ...

to control their regulators; he voted against the bill and stated he would not support confirmation of the first commissioners. The Clayton Antitrust Act

The Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914 (, codified at , ), is a part of United States antitrust law with the goal of adding further substance to the U.S. antitrust law regime; the Clayton Act seeks to prevent anticompetitive practices in their incipie ...

, Borah opined, was merely a means by which Congress could appear to be dealing with the trusts without actually doing so.

In 1913 and early 1914, Borah clashed with Wilson and his Secretary of State, Bryan, over Latin American policy. Borah believed that there was an ongoing temptation for the U.S. to expand into Latin America, which the construction of the Panama Canal had made worse. If the U.S. did so, the local population would have to be subjugated or incorporated into the American political structure, neither of which he deemed possible. Believing that nations should be left unmolested by greater powers, Borah decried American interference in Latin American governments; he and Wilson clashed over policy towards Mexico, then in the throes of revolution. Wilson decided that the Mexican government, led by Victoriano Huerta

José Victoriano Huerta Márquez (; 22 December 1854 – 13 January 1916) was a general in the Mexican Federal Army and 39th President of Mexico, who came to power by coup against the democratically elected government of Francisco I. Madero wi ...

, must pledge elections in which Huerta would not run before being recognized. Although Borah disliked Huerta as too close to the pre-revolutionary leadership, he felt that Mexicans should decide who ran Mexico, and argued against Wilson's plan.

After World War I began in 1914, it was Borah's view that the U.S. should keep completely out of it and he voted for legislation requested by Wilson barring armament shipments to the belligerents. Borah was disquieted when Wilson permitted credits to Great Britain and France after refusing them loans, as the credits served the same purpose, furthering the war. He was vigilant in support of the neutral rights

Neutral or neutrality may refer to:

Mathematics and natural science Biology

* Neutral organisms, in ecology, those that obey the unified neutral theory of biodiversity

Chemistry and physics

* Neutralization (chemistry), a chemical reaction i ...

of the United States, and was outraged both by the 1915 sinking of the ''Lusitania'' by the Germans and by infringements against Americans by British forces. Borah was spoken of as a possible candidate for president in 1916, but gained little support: the Old Guard disliked him almost as much as they did Roosevelt, while others questioned whether a man so free from the discipline of the party could lead its ranks. Borah stated he lacked the money to run. He did work behind the scenes to find a candidate that would reunite the Republicans and holdout Progressives: a member of a joint committee of the two parties' conventions to seek re-unification, Borah achieved a friendly reception when he addressed the Progressive convention. The Republicans nominated Charles Evans Hughes

Charles Evans Hughes Sr. (April 11, 1862 – August 27, 1948) was an American statesman, politician and jurist who served as the 11th Chief Justice of the United States from 1930 to 1941. A member of the Republican Party, he previously was the ...

, and Progressive leaders reluctantly backed him, but some former Roosevelt supporters refused to support Hughes. Borah campaigned for the Republican presidential candidate (something he would do only once more, for Hoover in 1928), but Wilson narrowly won re-election.

World War and Versailles treaty (1917–1920)

After Germany resumed unlimited submarine warfare in early 1917, many considered U.S. entry into the war inevitable, though Borah expressed hope it might still be avoided. Nevertheless, he supported Wilson on legislation to arm merchant ships, and voted in favor when the president requested a declaration of war in April 1917. He made it clear that in his view, the U.S. was going in to defend its own rights and had no common interest with the Allies beyond the defeat of the Central Powers. He repeated this often through the war: the United States sought no territory, and had no interest in French and British desires for territory and colonies. Borah, though a strong war supporter, was possibly the most prominent wartime advocate of progressive views, opposingthe draft

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day un ...

and the Espionage Act of 1917

The Espionage Act of 1917 is a United States federal law enacted on June 15, 1917, shortly after the United States entered World War I. It has been amended numerous times over the years. It was originally found in Title 50 of the U.S. Code (Wa ...

, and pressing Wilson for statements of limited war aims. Borah's term was to expire in 1919; never a wealthy person and hard-hit by the high cost of living in wartime Washington, he considered leaving the Senate and practicing law in a major New York firm. However, he felt needed in the Senate and in Idaho, as both of the state's seats would be up for election in November 1918 due to the death of Borah's junior colleague, James H. Brady. Even President Wilson urged Borah's re-election in a letter to former senator Dubois. Borah received two-thirds of the vote in his bid for a third term, while former governor Gooding narrowly won Brady's seat. Nationally, the Republicans retook control of the Senate with a 49–47 majority.

That the war would not last long beyond the election was clear in the final days of the 1918 congressional midterm election campaign, which was fought in part to decide which party would control the postwar peace process. Wilson hoped for a treaty based on the Fourteen Points

U.S. President Woodrow Wilson

The Fourteen Points was a statement of principles for peace that was to be used for peace negotiations in order to end World War I. The principles were outlined in a January 8, 1918 speech on war aims and peace term ...

and had urged formation of a postwar organization to assure peace. Borah, well aware the U.S. would play a large role at the peace table, saw such an organization as a trap that would inevitably involve the U.S. whenever conflict developed in Europe. He decided to oppose Wilson's plan despite his personal admiration for the president.

Like many Westerners, Borah held agrarian ideals, and linked them with a policy of isolationism and avoiding foreign entanglements he believed had served the nation well. Borah took pains, throughout the battle, to stress that he had opposed the principle of a league before it became a partisan issue; according to McKenna, in Borah's League fight, "of partisanship, jealousy, or personal hostility there is no trace".

Republicans felt Wilson was making a political issue of the peace, especially when the president urged a Democratic Congress prior to the 1918 election, and attended the Paris Peace Conference in person, taking no Republicans on his delegation. Wilson had felt his statement was the only chance of getting a Senate that might ratify a treaty for a postwar organization to keep the peace, and deemed conciliation pointless. In Paris, Wilson and other leaders negotiated what would become the

Republicans felt Wilson was making a political issue of the peace, especially when the president urged a Democratic Congress prior to the 1918 election, and attended the Paris Peace Conference in person, taking no Republicans on his delegation. Wilson had felt his statement was the only chance of getting a Senate that might ratify a treaty for a postwar organization to keep the peace, and deemed conciliation pointless. In Paris, Wilson and other leaders negotiated what would become the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

, an international organization that world leaders hoped that through diplomacy, and if necessary, force, would assure peace. Republican senatorial opinion ranged from the Irreconcilables

{{for, Irreconcilables during the Philippine–American War , Irreconcilables (Philippines)

The Irreconcilables were bitter opponents of the Treaty of Versailles in the United States in 1919. Specifically, the term refers to about 12 to 18 United ...

like Borah, who would not support any organization, to those who strongly favored one; none wanted Wilson to go into the 1920 presidential election with credit for having sorted out Europe. Once the general terms of the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

, which included the Charter of the League of Nations, were presented by Wilson in February 1919, Henry Cabot Lodge

Henry Cabot Lodge (May 12, 1850 November 9, 1924) was an American Republican politician, historian, and statesman from Massachusetts. He served in the United States Senate from 1893 to 1924 and is best known for his positions on foreign policy ...

of Massachusetts, the incoming Senate Majority Leader

The positions of majority leader and minority leader are held by two United States senators and members of the party leadership of the United States Senate. They serve as the chief spokespersons for their respective political parties holding t ...

, decided on a strategy: rather than outright opposition, Republicans would offer reservations to the treaty that Wilson could not accept.

A week after Wilson presented the treaty, Borah declined an invitation to the White House extended to him and other Senate and House members on the foreign relations committees, alleging there was no chance of common ground, though he wrote to Wilson's private secretary

A private secretary (PS) is a civil servant in a governmental department or ministry, responsible to a secretary of state or minister; or a public servant in a royal household, responsible to a member of the royal family.

The role exists in ...

that no insult was intended. In the following months, Borah was a leader of the Irreconcilables. An especial target was Article X of the charter, obligating all members to defend each other's independence. The Irreconcilables argued that this would commit the U.S. to war without its consent; Borah stated that the U.S. might be forced to send thousands of men if there was conflict in Armenia. Other provisions were examined; Borah proposed that the U.S. representatives in Paris be asked to press the issue of Irish independence, but the Senate took no action. Borah found the provisions of the treaty regarding Germany to be shocking in their vindictiveness, and feared they might snuff out the new Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is al ...

at birth.

The small Republican majority in the Senate made Irreconcilable votes necessary to Lodge's strategy, and he met with Borah in April 1919, persuading him to go along with the plan of delay and reservations as the most likely to succeed, as it would allow the initial popular support for Wilson's proposal to diminish. Neither senator really liked or trusted the other, but they formed a wary pact to defeat the treaty. Lodge was also chairman of the

The small Republican majority in the Senate made Irreconcilable votes necessary to Lodge's strategy, and he met with Borah in April 1919, persuading him to go along with the plan of delay and reservations as the most likely to succeed, as it would allow the initial popular support for Wilson's proposal to diminish. Neither senator really liked or trusted the other, but they formed a wary pact to defeat the treaty. Lodge was also chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee

The United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations is a standing committee of the U.S. Senate charged with leading foreign-policy legislation and debate in the Senate. It is generally responsible for overseeing and funding foreign aid pro ...

and he delayed the treaty by convening a lengthy series of hearings, presiding over a committee packed with Irreconcilables, including Borah. As these hearings continued in the summer of 1919, Wilson undertook a speaking tour by train to get the public to press the Senate for ratification, a tour that ended in his collapse. In the months that followed, an ailing Wilson refused any compromise.

Borah helped write the majority report for the committee, recommending 45 amendments and 4 reservations. In November 1919, the Senate defeated both versions of the Treaty of Versailles, with and without what were called the Lodge Reservations

The Lodge Reservations, written by United States Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, the Republican Majority Leader and Chairman of the Committee on Foreign Relations, were fourteen reservations to the Treaty of Versailles and other proposed post-war agreem ...

. Borah, delighted, proclaimed the day the greatest since the end of the Civil War. The following January, the Senate considered the treaty again and Lodge wanted to convene a bipartisan group of senators to find a compromise. Borah, threatening party schism, met with Lodge behind closed doors, and Lodge withdrew his plan. The Senate voted once more, in March 1920, on the treaty with a version of the Lodge Reservations, and it failed again. According to Robert James Maddox in his book on Borah's influence on American foreign policy, the Irreconcilables "dictated to the majority leader as though they were the majority. Borah as much as any man deserves the credit—or the blame—for the League's defeat".Women's suffrage

Idaho had given women the right to vote in 1896, and Borah was a firm supporter of woman's suffrage. However, he did not support a constitutional amendment to accomplish this nationwide, feeling that states should not have the requirement that women vote imposed on them. Borah voted against the proposed amendment when it came up for a vote in 1914, and it did not pass. Activists felt that as a noted progressive, and as one who would face the voters for the first time as a senator in 1918, that he could be persuaded to support the amendment, and if not, unseated. When what would become the Nineteenth Amendment passed the House, Borah announced his opposition, writing to an Idahoan, "I am aware…y position

Y, or y, is the twenty-fifth and penultimate letter of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. According to some authorities, it is the sixth (or sevent ...

will lead to much criticism among friends at home utI would rather give up the office han

Han may refer to:

Ethnic groups

* Han Chinese, or Han People (): the name for the largest ethnic group in China, which also constitutes the world's largest ethnic group.

** Han Taiwanese (): the name for the ethnic group of the Taiwanese p ...

cast a vote…I do not believe in."

Activists determined to pressure Borah with petitions from his constituents, and former president Roosevelt sent him a note urging him to change his vote. This had no effect, and when the Senate voted on the amendment in early October 1918, it failed by two votes, with Borah voting in the negative. More petitions and pressure on Borah followed, and the senator agreed to meet with suffragist leader Alice Paul

Alice Stokes Paul (January 11, 1885 – July 9, 1977) was an American Quaker, suffragist, feminist, and women's rights activist, and one of the main leaders and strategists of the campaign for the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, w ...

. After the meeting, Paul stated that Borah had agreed to support the amendment if re-elected, but the senator said he had agreed to no such thing. Nevertheless, Paul called off the efforts to sway or defeat Borah, and the senator retained his seat by nearly a two-to-one margin.

During the lame duck session

A lame-duck session of Congress in the United States occurs whenever one Congress meets after its successor is elected, but before the successor's term begins. The expression is now used not only for a special session called after a sine die adjo ...

of Congress that followed the election, Borah issued no public statement as to how he would vote when the amendment was brought up again. In February 1919, the Senate voted again, and Borah voted no—the amendment failed by one vote. Several of the new senators who took office in March 1919 were pledged to support the amendment, and on June 4, the Senate voted again, with the House having previously voted to approve the amendment. It passed with a margin of two votes, and was sent to the states for ratification (which was completed in August 1920, but Borah again voted no, one of only eight Republicans to do so.

Harding and Coolidge years

Borah was determined to see that the Republican presidential candidate in 1920 was not pro-League. He supported his fellow Irreconcilable, California SenatorHiram Johnson

Hiram Warren Johnson (September 2, 1866August 6, 1945) was an American attorney and politician who served as the 23rd governor of California from 1911 to 1917. Johnson achieved national prominence in the early 20th century. He was elected in 191 ...

, who had been Roosevelt's running mate in 1912. Borah alleged bribery on the part of the leading candidate for the Republican nomination, General Leonard Wood

Leonard Wood (October 9, 1860 – August 7, 1927) was a United States Army major general, physician, and public official. He served as the Chief of Staff of the United States Army, Military Governor of Cuba, and Governor-General of the Philippi ...

, and was snubbed when he demanded to know the League views of Wood's main rival, Illinois Governor Frank Lowden

Frank Orren Lowden (January 26, 1861 – March 20, 1943) was an American Republican Party politician who served as the 25th Governor of Illinois and as a United States Representative from Illinois. He was also a candidate for the Republican pre ...

. When the 1920 Republican National Convention

The 1920 Republican National Convention nominated Ohio Senator Warren G. Harding for president and Massachusetts Governor Calvin Coolidge for vice president. The convention was held in Chicago, Illinois, at the Chicago Coliseum from June 8 t ...

met in Chicago in June, delegates faced a deadlock both as to who should head the ticket, and as to the contents of the League plank of the party platform. The League fight was decided, with Borah's endorsement, by using language proposed by former Secretary of State Elihu Root

Elihu Root (; February 15, 1845February 7, 1937) was an American lawyer, Republican politician, and statesman who served as Secretary of State and Secretary of War in the early twentieth century. He also served as United States Senator from ...

supporting ''a'' league, rather than ''the'' League. The presidential stalemate was harder to resolve. A hater both of political intrigue and of tobacco, Borah played no part in the smoke-filled room

In U.S. political jargon, a smoke-filled room (sometimes called a smoke-filled back room) is an exclusive, sometimes secret political gathering or round-table-style decision-making process. The phrase is generally used to suggest an inner circl ...

discussions as the Republicans attempted to break the deadlock. He was initially unenthusiastic about the eventual nominee, Ohio Senator Warren G. Harding

Warren Gamaliel Harding (November 2, 1865 – August 2, 1923) was the 29th president of the United States, serving from 1921 until his death in 1923. A member of the Republican Party, he was one of the most popular sitting U.S. presidents. ...

, his colleague on the Foreign Relations Committee, as he was disappointed at the failure of Johnson's candidacy and disliked Harding's vague stance on the League. Nevertheless, Borah strongly endorsed Harding and his running mate, Massachusetts Governor Calvin Coolidge, who were victorious. Borah later stated he would have left the Senate had Harding lost.

Borah proved as idiosyncratic as ever in his views with Harding as president. The original idea for the Washington Naval Conference

The Washington Naval Conference was a disarmament conference called by the United States and held in Washington, DC from November 12, 1921 to February 6, 1922. It was conducted outside the auspices of the League of Nations. It was attended by nine ...

of 1921–22 came from a resolution he introduced in December 1920. After the new Secretary of State, Charles Hughes, took the idea, Borah became an opponent, convinced the conference would lead the United States into the League of Nations through the back door. In 1921, when Harding nominated former president Taft as chief justice, Borah was one of four senators to oppose confirmation. Borah stated that Taft, at 63, was too old and as a politician had been absent for decades from the practice of law. In 1922 and 1923, Borah spoke against passage of the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill

The Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill (1918) was first introduced in the 65th United States Congress by Representative Leonidas C. Dyer, a Republican from St. Louis, Missouri, in the United States House of Representatives as H.R. 11279 in order “to prot ...

, which had passed the House. A strong supporter of state sovereignty, he believed that punishing state officials for failure to prevent lynchings was unconstitutional, and that if the states could not prevent such murders, federal legislation would do no good. The bill was defeated by filibuster

A filibuster is a political procedure in which one or more members of a legislative body prolong debate on proposed legislation so as to delay or entirely prevent decision. It is sometimes referred to as "talking a bill to death" or "talking out ...

in the Senate by Southern Democrats. When another bill was introduced in 1935 and 1938, Borah continued to speak against it, by that time saying that it was no longer needed, as the number of lynchings had dropped sharply.

Harding's death in August 1923 brought Calvin Coolidge to the White House. Borah had been dismayed by Harding's conservative views, and believed Coolidge had shown liberal tendencies as a governor. He met with Coolidge multiple times in late 1923, and found the new president interested in his ideas on policies foreign and domestic. Borah was encouraged when Coolidge included in his annual message to Congress a suggestion that he might open talks with the Soviet Union on trade—the Bolshevik government had not been recognized since the 1917

Harding's death in August 1923 brought Calvin Coolidge to the White House. Borah had been dismayed by Harding's conservative views, and believed Coolidge had shown liberal tendencies as a governor. He met with Coolidge multiple times in late 1923, and found the new president interested in his ideas on policies foreign and domestic. Borah was encouraged when Coolidge included in his annual message to Congress a suggestion that he might open talks with the Soviet Union on trade—the Bolshevik government had not been recognized since the 1917 October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key moment ...

and Borah had long urged relations. Under pressure from the Old Guard, Coolidge quickly walked back his proposal, depressing Borah, who concluded the president had deceived him. In early 1924, the Teapot Dome scandal

The Teapot Dome scandal was a bribery scandal involving the administration of United States President Warren G. Harding from 1921 to 1923. Secretary of the Interior Albert Bacon Fall had leased Navy petroleum reserves at Teapot Dome in W ...

broke, and although Coolidge had no involvement in the affair, some of the implicated cabinet officers, including Attorney General Harry Daugherty

Harry Micajah Daugherty (; January 26, 1860 – October 12, 1941) was an American politician. A key Ohio Republican political insider, he is best remembered for his service as Attorney General of the United States under Presidents Warren G. Hardi ...

, remained in office, backed by the Old Guard. Coolidge sought the support of Borah in the crisis; his price was Daugherty's firing. The president stalled Borah, and when Daugherty eventually resigned under pressure, it was due more to events than Borah. When the president was nominated for election in his own right at the 1924 Republican National Convention

Nineteen or 19 may refer to:

* 19 (number), the natural number following 18 and preceding 20

* one of the years 19 BC, AD 19, 1919, 2019

Films

* ''19'' (film), a 2001 Japanese film

* ''Nineteen'' (film), a 1987 science fiction film

Music ...

, he offered the vice presidential nomination to Borah. By one account, when Coolidge asked Borah to join the ticket, the senator asked which position on it he was to occupy. The prospect of Borah as vice president appalled Coolidge's cabinet members and other Republican officials, and they were relieved when he refused. Borah spent less than a thousand dollars on his Senate re-election campaign that fall, and gained a fourth term with just under 80 percent of the vote. Coolidge and his vice-presidential choice, Charles G. Dawes

Charles Gates Dawes (August 27, 1865 – April 23, 1951) was an American banker, general, diplomat, composer, and Republican politician who was the 30th vice president of the United States from 1925 to 1929 under Calvin Coolidge. He was a co-rec ...

easily won, though Borah did no campaigning for the Coolidge/Dawes ticket, alleging his re-election bid required his full attention.

Senator Lodge died in November 1924, making Borah the senior member of the Foreign Relations Committee, and he took its chairmanship. He could have become Judiciary Committee chairman instead, as the death of Frank Brandegee of Connecticut made Borah senior Republican on that committee as well. The Foreign Relations chairmanship greatly increased his influence, one quip was that the new Secretary of State, Frank B. Kellogg

Frank Billings Kellogg (December 22, 1856December 21, 1937) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served in the U.S. Senate and as U.S. Secretary of State. He co-authored the Kellogg–Briand Pact, for which he was awarded the N ...

, created policy by ringing Borah's doorbell. Borah continued to oppose American interventions in Latin America, often splitting from the Republican majority over the matter. Borah was an avid horseback rider, and Coolidge is supposed to have commented after viewing him exercising in Rock Creek Park

Rock Creek Park is a large urban park that bisects the Northwest quadrant of Washington, D.C. The park was created by an Act of Congress in 1890 and today is administered by the National Park Service. In addition to the park proper, the Rock Cr ...

that it "must bother the Senator to be going in the same direction as his horse".

Borah was involved through the 1920s in efforts for the outlawry of war. Chicago lawyer Salmon Levinson, who had formulated the plan to outlaw war, labored long to get the mercurial Borah on board as its spokesman. Maddox suggested that Borah was most enthusiastic about this plan when he needed it as a constructive alternative to defeat actions such as entry into the World Court

The International Court of Justice (ICJ; french: Cour internationale de justice, links=no; ), sometimes known as the World Court, is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN). It settles disputes between states in accordanc ...

, that he deemed entangling the U.S. abroad. By the time of the 1924 election, Levinson was frustrated with Borah, but Coolidge's statement after the election that outlawry was one of the issues he proposed to address, briefly resurrected Borah's enthusiasm. only to have it fall away again. It was not until 1927, when French Foreign Minister Aristide Briand

Aristide Pierre Henri Briand (; 28 March 18627 March 1932) was a French statesman who served eleven terms as Prime Minister of France during the French Third Republic. He is mainly remembered for his focus on international issues and reconcili ...

proposed the U.S. and his nation enter into an agreement to "outlaw war" that Borah became interested again, though it took months of pestering by Levinson. In December 1927, Borah introduced a resolution calling for a multilateral version of Briand's proposal, and once the Kellogg–Briand Pact

The Kellogg–Briand Pact or Pact of Paris – officially the General Treaty for Renunciation of War as an Instrument of National Policy – is a 1928 international agreement on peace in which signatory states promised not to use war to ...

was negotiated and signed by various nations, secured ratification for that treaty by the Senate.

Hoover and FDR

Borah hoped to be elected president in 1928, but his only chance was a deadlocked Republican convention. He was reluctant to support Secretary of CommerceHerbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party, holding office during the onset of the Gre ...

for president, backing Ohio Senator Frank Willis instead, but after Willis collapsed and died at a campaign rally in late March, Borah began to find Hoover more to his liking. The Idahoan's support for Hoover became more solid as the campaign began to shape as a rural/urban divide. Borah was a strong backer of Prohibition, and the fact that Hoover was another "dry" influenced Borah in his support; the senator disliked the Democratic candidate, New York Governor Al Smith

Alfred Emanuel Smith (December 30, 1873 – October 4, 1944) was an American politician who served four terms as Governor of New York and was the Democratic Party's candidate for president in 1928.

The son of an Irish-American mother and a Civ ...

, an opponent of Prohibition, considering him a creature of Tammany Hall

Tammany Hall, also known as the Society of St. Tammany, the Sons of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was a New York City political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789 as the Tammany Society. It became the main loc ...

. Though Montana Senator Thomas J. Walsh commented on "Borah's recent conversion to Hoover", and some progressives were disheartened, Borah undertook a lengthy campaign tour, warning that he saw "the success of Tammany in national politics as nothing less than a national disaster". Hoover was elected and thanked Borah for "the enormous effect" of his support. He offered to make Borah Secretary of State, though deploring the loss to the Senate, but Borah declined.

Borah was not personally harmed by the stock market crash of October 1929, having sold any stocks and invested in government bonds. Thousands of Americans had borrowed on margin, and were ruined by the crash. Congress in June 1930 passed the Hawley–Smoot Tariff, sharply increasing rates on imports. Borah was one of 12 Republicans who joined Democrats in opposing the bill, which passed the Senate 44–42. Borah was up for election in 1930, and despite a minimal campaign effort, took over 70 percent of the vote in a bad year for Republicans. When he returned to Washington for the