William Dudley Pelley on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

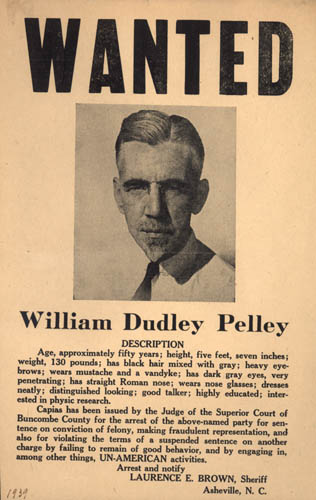

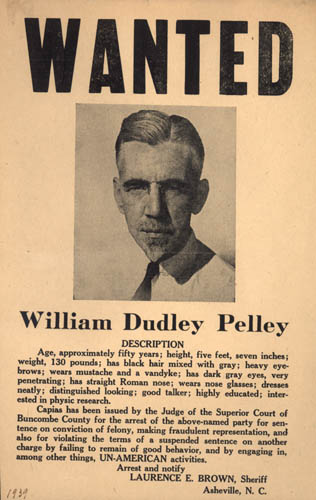

William Dudley Pelley (March 12, 1890 – June 30, 1965) was an American

William Dudley Pelley (March 12, 1890 – June 30, 1965) was an American

''The New York Times'', July 2, 1965. Retrieved: May 9, 2016.

Jon Elliston, "New Age Nazi: The Rise and Fall of Asheville's Flaky Fascist", ''Mountain Xpress'', January 28, 2004

''The Greater Glory'', a novel by Pelley at archive.org

''The Fog'', a novel by Pelley at archive.org

* William Dudley Pelley discussed i

Episode 3Episode 7

an

Episode 8

of Rachel Maddow's ''Ultra'' podcast (2022) {{DEFAULTSORT:Pelley, William Dudley 1890 births 1965 deaths Candidates in the 1936 United States presidential election 20th-century American politicians American anti-war activists American collaborators with Nazi Germany American fascists American male screenwriters Christian fascists Old Right (United States) People from Lynn, Massachusetts People from Noblesville, Indiana Screenwriters from Massachusetts Screenwriters from Indiana Screenwriters from North Carolina Writers from Asheville, North Carolina Fascist politicians 20th-century American male writers American anti-communists 20th-century American screenwriters Activists from North Carolina Activists from Indiana

William Dudley Pelley (March 12, 1890 – June 30, 1965) was an American

William Dudley Pelley (March 12, 1890 – June 30, 1965) was an American fascist

Fascism is a far-right, Authoritarianism, authoritarian, ultranationalism, ultra-nationalist political Political ideology, ideology and Political movement, movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and pol ...

leader, occult

The occult, in the broadest sense, is a category of esoteric supernatural beliefs and practices which generally fall outside the scope of religion and science, encompassing phenomena involving otherworldly agency, such as magic and mysticism a ...

ist, spiritualist

Spiritualism is the metaphysical school of thought opposing physicalism and also is the category of all spiritual beliefs/views (in monism and dualism) from ancient to modern. In the long nineteenth century

The ''long nineteenth century'' i ...

and writer.

Pelley came to prominence as a writer, winning two O. Henry Award

The O. Henry Award is an annual American award given to short stories of exceptional merit. The award is named after the American short-story writer O. Henry.

The ''PEN/O. Henry Prize Stories'' is an annual collection of the year's twenty best ...

s and penning screenplays for Hollywood films

The cinema of the United States, consisting mainly of major film studios (also known as Hollywood) along with some independent film, has had a large effect on the global film industry since the early 20th century. The dominant style of Ame ...

. His 1929 essay "Seven Minutes in Eternity" marked a turning point in his career, published in ''The American Magazine

''The American Magazine'' was a periodical publication founded in June 1906, a continuation of failed publications purchased a few years earlier from publishing mogul Miriam Leslie. It succeeded ''Frank Leslie's Popular Monthly'' (1876–1904), ' ...

'' as a popular example of what would later be called a near-death experience

A near-death experience (NDE) is a profound personal experience associated with death or impending death which researchers claim share similar characteristics. When positive, such experiences may encompass a variety of sensations including detac ...

. His antisemitism led him to found the Silver Legion of America

The Silver Legion of America, commonly known as the Silver Shirts, was an underground American fascist and Nazi sympathizer organization founded by William Dudley Pelley and headquartered in Asheville, North Carolina.

History

Pelley was a form ...

in 1933, a fascist paramilitary

A paramilitary is an organization whose structure, tactics, training, subculture, and (often) function are similar to those of a professional military, but is not part of a country's official or legitimate armed forces. Paramilitary units carr ...

league. He ran for president of the United States in 1936 as the candidate for the Christian Party.

Pelley was sentenced to 15 years in prison for sedition

Sedition is overt conduct, such as speech and organization, that tends toward rebellion against the established order. Sedition often includes subversion of a constitution and incitement of discontent toward, or insurrection against, estab ...

in 1942, and released in 1950. Upon his death, ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' assessed him as "an agitator without a significant following".

Early life

Born in Lynn,Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

, William Dudley Pelley grew up in poverty, the son of William George Apsey Pelley and his wife, Grace (née Goodale). His father was initially a Southern Methodist Church

The Southern Methodist Church is a conservative Protestant Christian denomination with churches located in the southern part of the United States. The church maintains headquarters in Orangeburg, South Carolina.

The church was formed in 1940 b ...

minister, and was later a small businessman and shoemaker.

Early career

Largely self-educated, Pelley became a journalist and gained respect for his writing skills; his articles eventually appeared in national publications such as ''The Chicago Tribune

The ''Chicago Tribune'' is a daily newspaper based in Chicago, Illinois, United States, owned by Tribune Publishing. Founded in 1847, and formerly self-styled as the "World's Greatest Newspaper" (a slogan for which WGN radio and television ar ...

''. Two of his short stories received O. Henry awards: "The Face in the Window" in 1920 and "The Continental Angle" in 1930. He was hired by the Methodist Centenary to study Methodist missions around the world. He joined the Red Cross

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a Humanitarianism, humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million Volunteering, volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure re ...

in Siberia, where he helped the White Russians during the Russian Civil War

, date = October Revolution, 7 November 1917 – Yakut revolt, 16 June 1923{{Efn, The main phase ended on 25 October 1922. Revolt against the Bolsheviks continued Basmachi movement, in Central Asia and Tungus Republic, the Far East th ...

. His opposition to Communism grew, and he began to subscribe to the conspiracy theory of Jewish Communism. Upon returning to the United States in 1920, Pelley wrote novels and short stories in addition to his journalism, and went to Hollywood, where he became a screenwriter, writing the Lon Chaney

Leonidas Frank "Lon" Chaney (April 1, 1883 – August 26, 1930) was an American actor. He is regarded as one of the most versatile and powerful actors of cinema, renowned for his characterizations of tortured, often grotesque and affli ...

films ''The Light in the Dark

''The Light in the Dark'' (later re-edited into a shorter version called ''The Light of Faith'') is a 1922 American silent drama film directed by Clarence Brown and stars Lon Chaney and Hope Hampton. A still exists showing Lon Chaney in the role ...

'' (1922) and '' The Shock'' (1923). Pelley became disillusioned with the film industry. What he regarded as unfair treatment by Jewish studio executives increased his antisemitic inclinations. He moved to New York, and then to Asheville

Asheville ( ) is a city in, and the county seat of, Buncombe County, North Carolina. Located at the confluence of the French Broad and Swannanoa rivers, it is the largest city in Western North Carolina, and the state's 11th-most populous cit ...

, North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and So ...

in 1932, and began publishing magazines and essays detailing his new religious system, the "Liberation Doctrine".

Spiritualism

In May 1928, Pelley gained notoriety when he claimed he had anout-of-body experience

An out-of-body experience (OBE or sometimes OOBE) is a phenomenon in which a person perceives the world from a location outside their physical body. An OBE is a form of autoscopy (literally "seeing self"), although this term is more commonly use ...

in which he traveled to other planes of existence devoid of corporeal souls. He described his experience in an article titled "My Seven Minutes in Eternity", published in book form in 1933 as ''Seven Minutes in Eternity: With the Aftermath'', originally probably appearing in ''The American Magazine

''The American Magazine'' was a periodical publication founded in June 1906, a continuation of failed publications purchased a few years earlier from publishing mogul Miriam Leslie. It succeeded ''Frank Leslie's Popular Monthly'' (1876–1904), ' ...

'' in the late 1920s. In later writings, he described the experience as "hypo-dimensional". He wrote that during this event, he met with God and Jesus, who instructed him to undertake the spiritual transformation of America. He later claimed that the experience gave him the ability to levitate

Levitation (from Latin ''levitas'' "lightness") is the process by which an object is held aloft in a stable position, without mechanical support via any physical contact.

Levitation is accomplished by providing an upward force that counteracts ...

, see through walls, and have out-of-body experiences at will. His metaphysical

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

writings greatly boosted his public visibility. Some of the early members of the original Ascended Master Teachings religion, the "I AM" Activity

The "I AM" Activity Movement is the original ascended master teachings religious movement founded in the early 1930s by Guy Ballard (1878–1939) and his wife Edna Anne Wheeler Ballard (1886–1971) in Chicago, Illinois.Saint Germain Found ...

, were recruited from the ranks of Pelley's organization, the Silver Legion of America

The Silver Legion of America, commonly known as the Silver Shirts, was an underground American fascist and Nazi sympathizer organization founded by William Dudley Pelley and headquartered in Asheville, North Carolina.

History

Pelley was a form ...

. Pelley's religious system was a mixture of theosophy

Theosophy is a religion established in the United States during the late 19th century. It was founded primarily by the Russian Helena Blavatsky and draws its teachings predominantly from Blavatsky's writings. Categorized by scholars of religion a ...

, spiritualism

Spiritualism is the metaphysical school of thought opposing physicalism and also is the category of all spiritual beliefs/views (in monism and dualism) from ancient to modern. In the long nineteenth century, Spiritualism (when not lowercase) ...

, Rosicrucianism

Rosicrucianism is a spiritual and cultural movement that arose in Europe in the early 17th century after the publication of several texts purported to announce the existence of a hitherto unknown esoteric order to the world and made seeking its ...

, and pyramidism. He considered it to be a perfected form of Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

, in which "Dark Souls" (Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

, Communists

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a so ...

and Papist

The words Popery (adjective Popish) and Papism (adjective Papist, also used to refer to an individual) are mainly historical pejorative words in the English language for Roman Catholicism, once frequently used by Protestants and Eastern Orthodox ...

s) represented the forces of evil.

Political activism

When theGreat Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

struck America in 1929, Pelley became active in politics. After moving to Asheville, Pelley founded Galahad College in 1932. The college specialized in correspondence courses

Distance education, also known as distance learning, is the education of students who may not always be physically present at a school, or where the learner and the teacher are separated in both time and distance. Traditionally, this usually in ...

on "Social Metaphysics" and "Christian Economics." He also founded Galahad Press, which he used to publish various political and metaphysical magazines, newspapers, and books. On January 30, 1933, Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

became chancellor of Germany

The chancellor of Germany, officially the federal chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany,; often shortened to ''Bundeskanzler''/''Bundeskanzlerin'', / is the head of the federal government of Germany and the commander in chief of the Ge ...

. Pelley, an admirer of Hitler, founded the Silver Legion, an antisemitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

organization whose members, known as Silver Shirts and Christian Patriots, wore Nazi-style silver uniform shirts. Their insignia was a scarlet ''L'', emblazoned on their flags and uniforms. Biographer Scott Beekman noted that Pelley was "one of the first Americans to create an organization celebrating the work of Adolf Hitler."

Pelley traveled throughout the United States, holding recruitment rallies, lectures, and public speeches. He founded Silver Legion chapters in almost every state in the country. Membership peaked at 15,000 in 1935, dropping to below 5,000 by 1938. His political ideology consisted of anti-Communism

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when the United States and the ...

, antisemitism, patriotism

Patriotism is the feeling of love, devotion, and sense of attachment to one's country. This attachment can be a combination of many different feelings, language relating to one's own homeland, including ethnic, cultural, political or histor ...

, corporatism

Corporatism is a collectivist political ideology which advocates the organization of society by corporate groups, such as agricultural, labour, military, business, scientific, or guild associations, on the basis of their common interests. The ...

, isolationism

Isolationism is a political philosophy advocating a national foreign policy that opposes involvement in the political affairs, and especially the wars, of other countries. Thus, isolationism fundamentally advocates neutrality and opposes entang ...

, and British Israelism

British Israelism (also called Anglo-Israelism) is the British nationalist, pseudoarchaeological, pseudohistorical and pseudoreligious belief that the people of Great Britain are "genetically, racially, and linguistically the direct descendant ...

, themes which were the primary focus of his numerous magazines and newspapers which included ''Liberation'', ''Pelley's Silvershirt Weekly'', ''The Galilean,'' and ''The New Liberator''. He became fairly well known as the 1930s went on. Sinclair Lewis

Harry Sinclair Lewis (February 7, 1885 – January 10, 1951) was an American writer and playwright. In 1930, he became the first writer from the United States (and the first from the Americas) to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature, which was ...

mentioned him by name in his novel ''It Can't Happen Here

''It Can't Happen Here'' is a 1935 dystopian political novel by American author Sinclair Lewis. It describes the rise of a United States dictator similar to how Adolf Hitler gained power. The novel was adapted into a play by Lewis and John C. Mo ...

'' (1935) about a fascist takeover in the U.S. Pelley is praised by the leader of the fictional movement as an important precursor.

Pelley opposed Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

and the New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Cons ...

. He founded the Christian Party in 1935, and ran an unsuccessful campaign as candidate for president in 1936, winning only 1,600 votes. He engaged in a long dispute with the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the Lower house, lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the United States Senate, Senate being ...

' Dies Committee

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly dubbed the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), was an investigative committee of the United States House of Representatives, created in 1938 to investigate alleged disloy ...

, predecessor to the House Un-American Activities Committee

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly dubbed the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), was an investigative committee of the United States House of Representatives, created in 1938 to investigate alleged disloy ...

. In 1940, federal marshals conducted a raid on Pelley's headquarters in Asheville, arresting his followers and seizing his property.

Despite serious financial and material setbacks within his organization which resulted from lengthy court battles, Pelley continued to oppose Roosevelt, especially as diplomatic relations between the United States and the Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent fo ...

and Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

became strained in the early 1940s. Pelley accused Roosevelt of being a warmonger

A warmonger is someone who instigates war, or advocates war over peaceful solutions.

Warmonger may also refer to:

* ''Warmonger'' (novel), a 2002 novel based on the ''Doctor Who'' television series

* '' Warmonger: Operation Downtown Destruction' ...

and advocated isolationism

Isolationism is a political philosophy advocating a national foreign policy that opposes involvement in the political affairs, and especially the wars, of other countries. Thus, isolationism fundamentally advocates neutrality and opposes entang ...

. Roosevelt enlisted J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was an American law enforcement administrator who served as the first Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). He was appointed director of the Bureau of Investigation � ...

and the FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and its principal Federal law enforcement in the United States, federal law enforcement age ...

to investigate Pelley. Subsequently, the FBI interviewed subscribers to Pelley's newspapers and magazines.

Although the attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii, j ...

in December 1941 led Pelley to disband the Silver Legion, he continued to attack the government in his magazine, ''Roll Call'', which alarmed Roosevelt, Attorney General Francis Biddle

Francis Beverley Biddle (May 9, 1886 – October 4, 1968) was an American lawyer and judge who was the United States Attorney General during World War II. He also served as the primary American judge during the postwar Nuremberg Trials as well a ...

, and the House Un-American Activities Committee. After stating in one issue of ''Roll Call'' that the devastation of the Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor was worse than the government claimed, Pelley was arrested at his new base of operations in Noblesville, Indiana

Noblesville is a city in and the county seat of Hamilton County, Indiana, Hamilton County, Indiana, United States, a part of the north Indianapolis suburbs along the White River (Indiana), White River. The population was 51,969 at the 2010 Unite ...

, and in April 1942, he was charged with 12 counts of treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

and sedition

Sedition is overt conduct, such as speech and organization, that tends toward rebellion against the established order. Sedition often includes subversion of a constitution and incitement of discontent toward, or insurrection against, estab ...

. One charge was dropped, but he was tried in Indiana and convicted of the other 11 charges, mostly for making seditious statements and for obstructing military recruiting and fomenting insurrection

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

within the military. Pelley was sentenced to 15 years in prison. After serving eight years, he was paroled and released in 1950. While still incarcerated, he was one of 30 defendants in the "Mass Sedition Trial" of Nazi sympathizers which culminated in a mistrial after the death of the judge, Edward C. Eicher, in November 1944.

Later life

In his final years, Pelley dealt with charges ofsecurities fraud

Securities fraud, also known as stock fraud and investment fraud, is a deceptive practice in the stock or commodities markets that induces investors to make purchase or sale decisions on the basis of false information, frequently resulting in los ...

that had been brought against him while he was living in Asheville.

The terms of Pelley's parole stipulated that he remain in central Indiana, and desist from all political activity. He developed an elaborate religious philosophy called "Soulcraft" based on his belief in UFOs

An unidentified flying object (UFO), more recently renamed by US officials as a UAP (unidentified aerial phenomenon), is any perceived aerial phenomenon that cannot be immediately identified or explained. On investigation, most UFOs are id ...

and extraterrestrials

Extraterrestrial life, colloquially referred to as alien life, is life that may occur outside Earth and which did not originate on Earth. No extraterrestrial life has yet been conclusively detected, although efforts are underway. Such life might ...

, and published ''Star Guests'' in 1950. Pelley died at his home in Noblesville

Noblesville is a city in and the county seat of Hamilton County, Indiana, United States, a part of the north Indianapolis suburbs along the White River. The population was 51,969 at the 2010 census making it the state's 14th largest city/town ...

, Indiana on June 30, 1965."William Dudley Pelley, 75, dies; Founded fascist Silver Shirts."''The New York Times'', July 2, 1965. Retrieved: May 9, 2016.

Filmography

*'' A Case at Law'' (1917) *''One-Thing-at-a-Time O'Day

''One-Thing-at-a-Time O'Day'' is a lost film, lost 1919 American silent comedy film, directed by John Ince (actor), John Ince. It stars Bert Lytell, Joseph Kilgour, and Eileen Percy, and was released on June 23, 1919.

Cast

* Bert Lytell as Strad ...

'' (1919)

*''What Women Love

''What Women Love'' is a lost 1920 American silent comedy drama film directed by Nate Watt and starring Annette Kellerman.

Cast

*Annette Kellerman as Annabel Cotton

* Ralph Lewis as James King Cotton

*Wheeler Oakman as Willy St. John

*William ...

'' (1920)

*''The Light in the Dark

''The Light in the Dark'' (later re-edited into a shorter version called ''The Light of Faith'') is a 1922 American silent drama film directed by Clarence Brown and stars Lon Chaney and Hope Hampton. A still exists showing Lon Chaney in the role ...

'' (1922)

*''Back Fire

''Back Fire'' is a 1922 American silent Western film directed by Alan James and starring Jack Hoxie, Florence Gilbert, and Lew Meehan

James Lew Meehan (September 7, 1890 – August 10, 1951) was an American film actor.

Meehan appear ...

'' (1922)

*''The Fog

''The Fog'' is a 1980 American supernatural horror film directed by John Carpenter, who also co-wrote the screenplay and created the music for the film. It stars Adrienne Barbeau, Jamie Lee Curtis, Tom Atkins, Janet Leigh and Hal Holbrook. It ...

'' (1923)

*'' As a Man Lives'' (1923)

*'' Her Fatal Millions'' (1923)

*'' The Shock'' (1923)

*'' Ladies to Board'' (1924)

*''The Sawdust Trail

''The Sawdust Trail'' is a 1924 American silent film, silent Western (genre), Western film produced and distributed by Universal Pictures and starring Hoot Gibson. Edward Sedgwick directed. It is based on the short story "Courtin' Calamity" by W ...

'' (1924)

*''Torment

Torment may refer to:

* The feeling of pain or suffering

* Causing to suffer, torture

Films

* ''Torment'' (1924 film), a silent crime-drama

* ''Torment'' (1944 film) (''Hets''), a Swedish film

* ''Torment'' (1950 British film), a British thr ...

'' (1924)

*''The Ladybird

''The Ladybird'' is a long tale or novella by D. H. Lawrence.

It was first drafted in 1915 as a short story entitled ''The Thimble''. Lawrence rewrote and extended it under a new title in December 1921 and sent the final version to his Engli ...

'' (1927)

*'' The Sunset Derby'' (1927)

*'' Come Across'' (1929)

*'' Drag'' (1929)

*''Courtin' Wildcats

''Courtin' Wildcats'' is a 1929 American silent film, silent comedy film, comedy Western (genre), Western film directed by Jerome Storm and produced by and starring Hoot Gibson. It is based on the short story "Courtin' Calamity" by William Dudle ...

'' (1929)

References

Notes

Bibliography

* Abella, Alex and Scott Gordon. ''Shadow Enemies''. Guilford, Connecticut: The Lyons Press, 2002, . * Beekman, Scott. William Dudley Pelley: A Life in Right-wing Extremism and the Occult. Syracuse University Press, 2005. .External links

* *Jon Elliston, "New Age Nazi: The Rise and Fall of Asheville's Flaky Fascist", ''Mountain Xpress'', January 28, 2004

''The Greater Glory'', a novel by Pelley at archive.org

''The Fog'', a novel by Pelley at archive.org

* William Dudley Pelley discussed i

Episode 3

an

Episode 8

of Rachel Maddow's ''Ultra'' podcast (2022) {{DEFAULTSORT:Pelley, William Dudley 1890 births 1965 deaths Candidates in the 1936 United States presidential election 20th-century American politicians American anti-war activists American collaborators with Nazi Germany American fascists American male screenwriters Christian fascists Old Right (United States) People from Lynn, Massachusetts People from Noblesville, Indiana Screenwriters from Massachusetts Screenwriters from Indiana Screenwriters from North Carolina Writers from Asheville, North Carolina Fascist politicians 20th-century American male writers American anti-communists 20th-century American screenwriters Activists from North Carolina Activists from Indiana