William Cornwallis on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

When war was officially declared, the

When war was officially declared, the

Between 9 April 1782 and 12 April 1782, ''Canada'' made up part of the fleet of Admiral Rodney at the

Between 9 April 1782 and 12 April 1782, ''Canada'' made up part of the fleet of Admiral Rodney at the

On 16 June 1795 he was in command of a small squadron that sighted a much larger French fleet. The ensuing action became famously known as " The Retreat of Cornwallis."

Cornwallis was cruising near

On 16 June 1795 he was in command of a small squadron that sighted a much larger French fleet. The ensuing action became famously known as " The Retreat of Cornwallis."

Cornwallis was cruising near

Cornwallis was promoted

Cornwallis was promoted

Dispatches and letters relating to the blockade of Brest, 1803–1805

Admiral of the Red

The Admiral of the Red was a senior rank of the Royal Navy of the United Kingdom, immediately outranked by the rank Admiral of the Fleet (see order of precedence below). The rank did not exist prior to 1805, as the admiral commanding the Red ...

Sir William Cornwallis, (10 February 17445 July 1819) was a Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

officer. He was the brother of Charles Cornwallis

Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis, (31 December 1738 – 5 October 1805), styled Viscount Brome between 1753 and 1762 and known as the Earl Cornwallis between 1762 and 1792, was a British Army general and official. In the United S ...

, the 1st Marquess Cornwallis, British commander at the siege of Yorktown

The Siege of Yorktown, also known as the Battle of Yorktown, the surrender at Yorktown, or the German battle (from the presence of Germans in all three armies), beginning on September 28, 1781, and ending on October 19, 1781, at Yorktown, Virgi ...

. Cornwallis took part in a number of decisive battles including the siege of Louisbourg in 1758, when he was 14, and the Battle of the Saintes

The Battle of the Saintes (known to the French as the Bataille de la Dominique), also known as the Battle of Dominica, was an important naval battle in the Caribbean between the British and the French that took place 9–12 April 1782. The Brit ...

but is best known as a friend of Lord Nelson

Vice-admiral (Royal Navy), Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronte (29 September 1758 – 21 October 1805) was a British people, British flag officer in the Royal Navy. His inspirational leadership, grasp of strate ...

and as the commander-in-chief of the Channel Fleet during the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

. He is depicted in the Horatio Hornblower novel, ''Hornblower and the Hotspur

''Hornblower and the Hotspur'' (published 1962) is a Horatio Hornblower novel written by C. S. Forester.

It is the third book in the series chronologically, but the tenth by order of publication, and serves as the basis for one of the episodes ...

''.

His affectionate contemporary nickname from "the ranks" was Billy Blue, and a sea shanty

A sea shanty, chantey, or chanty () is a genre of traditional Folk music, folk song that was once commonly sung as a work song to accompany rhythmical labor aboard large Merchant vessel, merchant Sailing ship, sailing vessels. The term ''shanty ...

was written during his period of service, reflecting the admiration his men had for him.

Early life

William Cornwallis was born 10 February 1744. His father wasCharles

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English language, English and French language, French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic, Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*k ...

, the fifth baron

Baron is a rank of nobility or title of honour, often hereditary, in various European countries, either current or historical. The female equivalent is baroness. Typically, the title denotes an aristocrat who ranks higher than a lord or knig ...

and first earl

Earl () is a rank of the nobility in the United Kingdom. The title originates in the Old English word ''eorl'', meaning "a man of noble birth or rank". The word is cognate with the Scandinavian form ''jarl'', and meant "chieftain", particular ...

Cornwallis, and his mother was Elizabeth, daughter of Viscount

A viscount ( , for male) or viscountess (, for female) is a title used in certain European countries for a noble of varying status.

In many countries a viscount, and its historical equivalents, was a non-hereditary, administrative or judicial ...

Charles Townshend

Charles Townshend (28 August 1725 – 4 September 1767) was a British politician who held various titles in the Parliament of Great Britain. His establishment of the controversial Townshend Acts is considered one of the key causes of the Ame ...

. William was the younger brother of General Charles Cornwallis

Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis, (31 December 1738 – 5 October 1805), styled Viscount Brome between 1753 and 1762 and known as the Earl Cornwallis between 1762 and 1792, was a British Army general and official. In the United S ...

.

Seven Years' War

The young William entered the navy in 1755 aboard the 80-gun bound for North America in the fleet ofAdmiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet, ...

Edward Boscawen

Admiral of the Blue Edward Boscawen, PC (19 August 171110 January 1761) was a British admiral in the Royal Navy and Member of Parliament for the borough of Truro, Cornwall, England. He is known principally for his various naval commands during ...

. Cornwallis was shortly after exchanged into and was present in her at the siege of Louisbourg in 1758. The siege was one of the pivotal battles of the war. Louisbourg

Louisbourg is an unincorporated community and former town in Cape Breton Regional Municipality, Nova Scotia.

History

The French military founded the Fortress of Louisbourg in 1713 and its fortified seaport on the southwest part of the harbour, ...

was the only deep water harbour that the French controlled in North America, and its capture enabled the British to launch an attack on Quebec City

Quebec City ( or ; french: Ville de Québec), officially Québec (), is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Quebec. As of July 2021, the city had a population of 549,459, and the Communauté métrop ...

. General James Wolfe

James Wolfe (2 January 1727 – 13 September 1759) was a British Army officer known for his training reforms and, as a Major-general (United Kingdom), major general, remembered chiefly for his victory in 1759 over the Kingdom of France, French ...

's attack on Quebec and victory at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham

The Battle of the Plains of Abraham, also known as the Battle of Quebec (french: Bataille des Plaines d'Abraham, Première bataille de Québec), was a pivotal battle in the Seven Years' War (referred to as the French and Indian War to describe ...

saw the beginning of the end of French colonisation in North America.

When ''Kingston'' returned to England in 1759, Cornwallis was taken aboard the 60-gun by Captain Robert Digby. During the planned French invasion of Britain in 1759, ''Dunkirk'' was with Admiral Edward Hawke

Edward Hawke, 1st Baron Hawke, KB, PC (21 February 1705 – 17 October 1781), of Scarthingwell Hall in the parish of Towton, near Tadcaster, Yorkshire, was a Royal Navy officer. As captain of the third-rate , he took part in the Battle of ...

's squadron and took part in the Battle of Quiberon Bay

The Battle of Quiberon Bay (known as ''Bataille des Cardinaux'' in French) was a decisive naval engagement during the Seven Years' War. It was fought on 20 November 1759 between the Royal Navy and the French Navy in Quiberon Bay, off the coast ...

against the French fleet under Admiral Conflans. The victory was part of what became known as ''Annus Mirabilis of 1759

Great Britain was one of the major participants in the Seven Years' War, which in fact lasted nine years, between 1754 and 1763. British involvement in the conflict began in 1754 in what became known as the French and Indian War. However the w ...

'' and in concert with the other victories of that year gave the Royal Navy almost complete dominance over the oceans for over a century. The succession of victories led Horace Walpole

Horatio Walpole (), 4th Earl of Orford (24 September 1717 – 2 March 1797), better known as Horace Walpole, was an English writer, art historian, man of letters, antiquarian, and Whigs (British political party), Whig politician.

He had Strawb ...

to remark "our bells are worn threadbare ringing for victories".

Cornwallis remained in ''Dunkirk'' when she was assigned to the Mediterranean fleet then commanded by Admiral Charles Saunders. ''Dunkirk'' was detached on blockade

A blockade is the act of actively preventing a country or region from receiving or sending out food, supplies, weapons, or communications, and sometimes people, by military force.

A blockade differs from an embargo or sanction, which are le ...

duty, ensuring the French fleet remained in the city of Heraklion

Heraklion or Iraklion ( ; el, Ηράκλειο, , ) is the largest city and the administrative capital of the island of Crete and capital of Heraklion regional unit. It is the fourth largest city in Greece with a population of 211,370 (Urban A ...

, Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, and ...

. Cornwallis moved to Saunders' flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the fi ...

where he remained for little over a year. On 5 April 1761, Cornwallis passed his examination for lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often sub ...

and was promoted into the newly commissioned third-rate

In the rating system of the Royal Navy, a third rate was a ship of the line which from the 1720s mounted between 64 and 80 guns, typically built with two gun decks (thus the related term two-decker). Years of experience proved that the third r ...

. In July 1761, Cornwallis was with ''Thunderer'' and two other line-of-battle ships blockading Cadiz. Two French ships escaped the blockade and the British squadron set off in pursuit. ''Thunderer'' caught up with the 64-gun and captured her in a single-ship action that lasted about half an hour. The British lost seventeen killed and one hundred and thirteen wounded.

In July 1762, Cornwallis received his first command in the 8-gun sloop-of-war

In the 18th century and most of the 19th, a sloop-of-war in the Royal Navy was a warship with a single gun deck that carried up to eighteen guns. The rating system covered all vessels with 20 guns and above; thus, the term ''sloop-of-war'' enc ...

. In 1763, he was given command of the more powerful and newly launched 14-gun . He continued in her into the peace with France after the Treaty of Paris Treaty of Paris may refer to one of many treaties signed in Paris, France:

Treaties

1200s and 1300s

* Treaty of Paris (1229), which ended the Albigensian Crusade

* Treaty of Paris (1259), between Henry III of England and Louis IX of France

* Trea ...

had ended the war in 1763. During the peace in 1765, he was promoted post-captain

Post-captain is an obsolete alternative form of the rank of Captain (Royal Navy), captain in the Royal Navy.

The term served to distinguish those who were captains by rank from:

* Officers in command of a naval vessel, who were (and still are) ...

and given command of the 44-gun . He commanded her until she was paid off

Ship commissioning is the act or ceremony of placing a ship in active service and may be regarded as a particular application of the general concepts and practices of project commissioning. The term is most commonly applied to placing a warship in ...

and the ship was sold in 1766. In September of the same year, he was given command of and was variously employed throughout the peace between the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

and the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

.

American Revolutionary War

When the French lent their official support to the American cause in 1778 with the Treaty of Alliance and the Treaty of Amity and Commerce, the war between Britain and the United States became aglobal war

A world war is an international conflict which involves all or most of the world's major powers. Conventionally, the term is reserved for two major international conflicts that occurred during the first half of the 20th century, World WarI (1914 ...

. Captain Cornwallis was in command of the newly commissioned . ''Lion'' was sent, with Admiral John Byron

Vice-Admiral John Byron (8 November 1723 – 1 April 1786) was a British Royal Navy officer and explorer. He earned the nickname "Foul-Weather Jack" in the press because of his frequent encounters with bad weather at sea. As a midshipman, he sa ...

, to the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

.

Battle of Grenada

When war was officially declared, the

When war was officially declared, the Comte d'Estaing

Jean Baptiste Charles Henri Hector, comte d'Estaing (24 November 1729 – 28 April 1794) was a French general and admiral. He began his service as a soldier in the War of the Austrian Succession, briefly spending time as a prisoner of war of the ...

, the French naval commander in North America swiftly captured the islands of Saint Vincent and Grenada

Grenada ( ; Grenadian Creole French: ) is an island country in the West Indies in the Caribbean Sea at the southern end of the Grenadines island chain. Grenada consists of the island of Grenada itself, two smaller islands, Carriacou and Pe ...

. Byron on hearing the news that Saint Vincent had been captured assembled his forces but on his way to recapture the island he received intelligence that d'Estaing and his fleet were in the process of capturing Grenada. Byron consequently took his fleet to Grenada in the hopes of engaging them and preventing the capture of Grenada. The island however had only held out for two days and was already in French hands.

The Battle of Grenada

The Battle of Grenada took place on 6 July 1779 during the American Revolutionary War in the West Indies between the British Royal Navy and the French Navy, just off the coast of Grenada. The British fleet of Admiral John Byron (the grandfath ...

took place on 6 July 1779. d'Estaing saw the British fleet of 21 ships of the line approaching and weighed anchor. Byron gave chase and attempted to form line of battle as per the Sailing and Fighting Instructions set down by Admiral Blake in 1653. d'Estaing, realising that his force although superior in guns was not so in numbers, had ordered his captains not to engage directly but to bear away when British ships approached and to bear down on any individual ship that might through wind or poor seamanship become separated from the line.

This tactic proved successful and d'Estaing's ships managed to escape the superior force causing considerable damage to three of the British ships. Cornwallis ''Lion'' was one of those ships and when he became separated from the British fleet she was forced to break away and make a run for Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

rather than risk capture. ''Lion'' suffered a reported 21 killed and 30 wounded.

Duty in the West Indies

During his time in the West Indies, Cornwallis came to own, then later free the "doctoress"Cubah Cornwallis

Cubah Cornwallis (died 1848) (often spelled Coubah, Couba, Cooba or Cuba) was a nurse or "doctress" and Obeah woman who lived in the colony of Jamaica during the late 18th and 19th century.

Early life

Little is known of her early life although re ...

. Cubah became Cornwallis' mistress and housekeeper in Port Royal, Jamaica. Later she treated Cornwallis' friend, Captain Horatio Nelson

Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronte (29 September 1758 – 21 October 1805) was a British flag officer in the Royal Navy. His inspirational leadership, grasp of strategy, and unconventional tactics brought abo ...

on his return from the disastrous mission to Nicaragua

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest country in Central America, bordered by Honduras to the north, the Caribbean to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Managua is the cou ...

. She also treated Prince William Henry

Prince William Henry, Duke of Gloucester and Edinburgh, (25 November 1743 – 25 August 1805), was a grandson of King George II and a younger brother of George III of the United Kingdom.

Life

Youth

Prince William Henry was born at Leicester ...

, later William IV, when he was stationed in the West Indies.

''Lion'' remained on the Jamaica station under the orders of Admiral Peter Parker

Spider-Man is a superhero appearing in American comic books published by Marvel Comics. Created by writer-editor Stan Lee and artist Steve Ditko, he first appearance, first appeared in the anthology comic book ''Amazing Fantasy'' #15 (August ...

and when she was repaired began a series of cruises in the West Indies. On 20 April 1780 Cornwallis was in command of a small squadron of two line-of-battle ships, ''Lion'' and and one large 44-gun frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied somewhat.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and ...

, .

Off Saint-Domingue

Saint-Domingue () was a French colony in the western portion of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, in the area of modern-day Haiti, from 1659 to 1804. The name derives from the Spanish main city in the island, Santo Domingo, which came to refer ...

the small British squadron discovered a convoy under the protection of four ships-of-the-line and one frigate commanded by Monsieur de la Motte Picquet. The French chased and the British ran. The French outsailed the British ships and when in range opened fire. The chase continued throughout the night and into the morning of the 21st. The breeze died and the two squadrons began to repair their damage. When the wind blew once more the chase renewed and continued throughout the night of the 21st and into the 22nd.

On the morning of the 22nd three sails appeared to leeward

Windward () and leeward () are terms used to describe the direction of the wind. Windward is ''upwind'' from the point of reference, i.e. towards the direction from which the wind is coming; leeward is ''downwind'' from the point of reference ...

. The arrival of these new sails would determine the outcome of the battle. The newcomers proved to be the 64-gun , the 32-gun and the 28-gun . The French squadron bore away for Cap-Français, leaving the two small British squadrons to repair and make for Jamaica. The British squadron under Cornwallis had lost 12 killed including Captain Glover of the ''Janus''.

Cornwallis returned to England in ''Lion'' in June 1781 and took part in the second relief of Gibraltar. He was appointed to command the 74-gun

The "seventy-four" was a type of two- decked sailing ship of the line, which nominally carried 74 guns. It was developed by the French navy in the 1740s, replacing earlier classes of 60- and 62-gun ships, as a larger complement to the recently-de ...

third-rate

In the rating system of the Royal Navy, a third rate was a ship of the line which from the 1720s mounted between 64 and 80 guns, typically built with two gun decks (thus the related term two-decker). Years of experience proved that the third r ...

, and immediately returned to the West Indies under the orders of Admiral Samuel Hood, 1st Viscount Hood.

''Canada'' was with Hood's fleet at the Battle of St. Kitts

The Battle of Saint Kitts, also known as the Battle of Frigate Bay, was a naval battle fought on 25 and 26 January 1782 during the American Revolutionary War between a British fleet under Rear Admiral Sir Samuel Hood and a larger French fleet u ...

in 1782. Hood took his 21 ships of the line and lured the French fleet of 29 ships of the line under the Comte de Grasse

''Comte'' is the French, Catalan and Occitan form of the word 'count' (Latin: ''comes''); ''comté'' is the Gallo-Romance form of the word 'county' (Latin: ''comitatus'').

Comte or Comté may refer to:

* A count in French, from Latin ''comes''

* A ...

from its anchorage at Basseterre

Basseterre (; Saint Kitts Creole: ''Basterre'') is the capital and largest city of Saint Kitts and Nevis with an estimated population of 14,000 in 2018. Geographically, the Basseterre port is located at , on the south western coast of Saint Kitt ...

on St. Kitts and then sailed into the roadstead

A roadstead (or ''roads'' – the earlier form) is a body of water sheltered from rip currents, spring tides, or ocean swell where ships can lie reasonably safely at anchor without dragging or snatching.United States Army technical manual, TM 5- ...

and anchored. Hood then repulsed de Grasse's efforts to dislodge the British fleet. The Battle of Brimstone Hill

Brimstone Hill Fortress National Park is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, a well-preserved fortress on a hill on the island of St. Kitts in the Federation of St. Christopher (St. Kitts) and Nevis in the Eastern Caribbean. It was designed by British ...

sealed the fate of the island despite Hood's efforts and St. Kitts fell into French hands. With the island in enemy hands and the French fleet cruising off the harbour, Hood was forced to withdraw and made his way to Antigua

Antigua ( ), also known as Waladli or Wadadli by the native population, is an island in the Lesser Antilles. It is one of the Leeward Islands in the Caribbean region and the main island of the country of Antigua and Barbuda. Antigua and Bar ...

. ''Canada'' in Commodore

Commodore may refer to:

Ranks

* Commodore (rank), a naval rank

** Commodore (Royal Navy), in the United Kingdom

** Commodore (United States)

** Commodore (Canada)

** Commodore (Finland)

** Commodore (Germany) or ''Kommodore''

* Air commodore ...

Edmund Affleck's division suffered 1 killed and 12 wounded. On 22 March Hood joined Admiral George Rodney

Admiral George Brydges Rodney, 1st Baron Rodney, KB ( bap. 13 February 1718 – 24 May 1792), was a British naval officer. He is best known for his commands in the American War of Independence, particularly his victory over the French at th ...

's fleet in Barbados

Barbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the Caribbean region of the Americas, and the most easterly of the Caribbean Islands. It occupies an area of and has a population of about 287,000 (2019 estimate). ...

.

Battle of the Saintes

Between 9 April 1782 and 12 April 1782, ''Canada'' made up part of the fleet of Admiral Rodney at the

Between 9 April 1782 and 12 April 1782, ''Canada'' made up part of the fleet of Admiral Rodney at the Battle of the Saintes

The Battle of the Saintes (known to the French as the Bataille de la Dominique), also known as the Battle of Dominica, was an important naval battle in the Caribbean between the British and the French that took place 9–12 April 1782. The Brit ...

. During the battle, Cornwallis and ''Canada'' were fourth in line on the starboard

Port and starboard are nautical terms for watercraft and aircraft, referring respectively to the left and right sides of the vessel, when aboard and facing the bow (front).

Vessels with bilateral symmetry have left and right halves which are ...

tack in the centre division between and . ''Canada'' sustained 35 casualties in total with 12 killed and the rest wounded. The outcome of the battle meant that the French and Spanish abandoned their planned invasion of Britain's most valuable Caribbean island, Jamaica. The battle, although a victory for the English caused a great deal of controversy in later years that included Cornwallis' direct criticism in writing of Rodney. The final couplet

A couplet is a pair of successive lines of metre in poetry. A couplet usually consists of two successive lines that rhyme and have the same metre. A couplet may be formal (closed) or run-on (open). In a formal (or closed) couplet, each of the ...

of the poem said to have been written in Cornwallis' own hand reads:

It appears that the criticisms of Admiral Hood and Cornwallis went unheard and Rodney was created a baron and given a life pension of £2,000 per year. Cornwallis was sent home under Rear-Admiral Thomas Graves with the convoy that included the captured French flagship . A violent storm hit the convoy and ''Ville de Paris'' sank along with several of the convoy and one of the escorts, . The convoy and her escorts finally arrived at Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

and ''Canada'' was paid off in October 1782.

Home service and peace

In January 1783 Cornwallis was given command of and in March of the same year was moved to HM Yacht ''Charlotte''. The American Revolutionary War between Britain and the allied forces of America and France ended with Britain's defeat in September 1783 and the subsequent signing of theTreaty of Paris Treaty of Paris may refer to one of many treaties signed in Paris, France:

Treaties

1200s and 1300s

* Treaty of Paris (1229), which ended the Albigensian Crusade

* Treaty of Paris (1259), between Henry III of England and Louis IX of France

* Trea ...

. With the peace came the downsizing of the navy. Cornwallis however remained employed in command of the royal yacht

A royal yacht is a ship used by a monarch or a royal family. If the monarch is an emperor the proper term is imperial yacht. Most of them are financed by the government of the country of which the monarch is head. The royal yacht is most often c ...

until 1787. In 1787 he was briefly given command of before hoisting his broad pennant

A broad pennant is a triangular swallow-tailed naval pennant flown from the masthead of a warship afloat or a naval headquarters ashore to indicate the presence of either:

(a) a Royal Navy officer in the rank of Commodore, or

(b) a U.S. Nav ...

as commodore in the 64-gun in October 1788 when he was appointed commander-in-chief of the East Indies Station

The East Indies Station was a formation and command of the British Royal Navy. Created in 1744 by the Admiralty, it was under the command of the Commander-in-Chief, East Indies.

Even in official documents, the term ''East Indies Station'' was ...

.

Third Anglo-Mysore War

In November 1791 Cornwallis ordered that French shipping be intercepted and searched for contraband. The British and French were not at war but the French were openly aiding theTipu Sultan

Tipu Sultan (born Sultan Fateh Ali Sahab Tipu, 1 December 1751 – 4 May 1799), also known as the Tiger of Mysore, was the ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore based in South India. He was a pioneer of rocket artillery.Dalrymple, p. 243 He int ...

in his war against the British. Cornwallis detached Captain Richard Strachan in to intercept the and two French merchant ships that were heading for the French held port of Mangalore

Mangalore (), officially known as Mangaluru, is a major port city of the Indian state of Karnataka. It is located between the Arabian Sea and the Western Ghats about west of Bangalore, the state capital, 20 km north of Karnataka–Ker ...

. The subsequent Battle of Tellicherry

The Battle of Tellicherry was a naval action fought off the Indian port of Tellicherry between British and French warships on 18 November 1791 during the Third Anglo-Mysore War. Britain and France were not at war at the time of the engagement, b ...

saw ''Phoenix'' capture and search all of the vessels. The local French commander was outraged and sent word back to France, but the French authorities were too busy with internal upheaval to pay the incident much notice.

French Revolutionary Wars

Though the conflict with Tipu Sultan was over, theFrench Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted French First Republic, France against Ki ...

had only begun. Promoted to rear-admiral on 1 February 1793, Cornwallis remained in the area and aided in the capture of Pondicherry, captaining his new flagship, the frigate , and commanding a small flotilla of three East Indiamen

East Indiaman was a general name for any sailing ship operating under charter or licence to any of the East India trading companies of the major European trading powers of the 17th through the 19th centuries. The term is used to refer to vesse ...

—''Triton'', ''Princess Charlotte'', and . He left command of Pondicherry to Captain King and returned to England, docking at Spithead

Spithead is an area of the Solent and a roadstead off Gilkicker Point in Hampshire, England. It is protected from all winds except those from the southeast. It receives its name from the Spit, a sandbank stretching south from the Hampshire ...

in August 1793. He was succeeded in command of the East Indies Station by Commodore (later Admiral) Peter Rainier.

In May 1794 he hoisted his flag aboard the 74-gun and was promoted vice-admiral of the blue squadron. In August he shifted his flag to the newer and larger 80-gun and then once more in December to the first rate

In the rating system of the British Royal Navy used to categorise sailing warships, a first rate was the designation for the largest ships of the line. Originating in the Jacobean era

The Jacobean era was the period in English and Scot ...

. Throughout this period he was in command of various divisions within the Channel Fleet

The Channel Fleet and originally known as the Channel Squadron was the Royal Navy formation of warships that defended the waters of the English Channel from 1854 to 1909 and 1914 to 1915.

History

Throughout the course of Royal Navy's history the ...

. The Channel Fleet was responsible for preventing invasion from France and for the blockade of French Channel ports.

First Battle of Groix

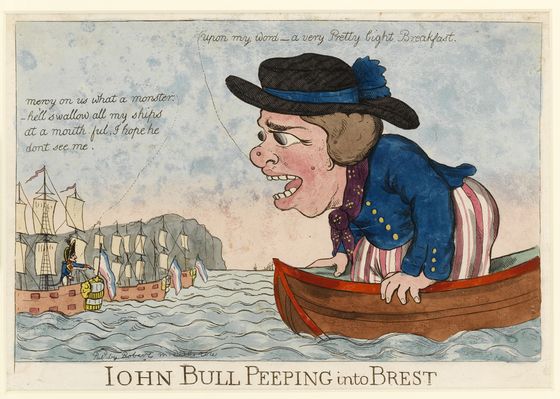

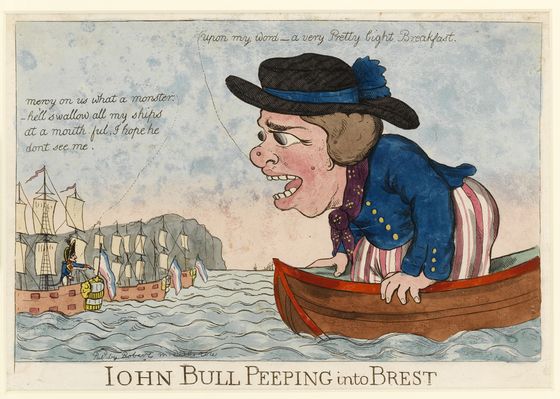

On 16 June 1795 he was in command of a small squadron that sighted a much larger French fleet. The ensuing action became famously known as " The Retreat of Cornwallis."

Cornwallis was cruising near

On 16 June 1795 he was in command of a small squadron that sighted a much larger French fleet. The ensuing action became famously known as " The Retreat of Cornwallis."

Cornwallis was cruising near Brest

Brest may refer to:

Places

*Brest, Belarus

**Brest Region

**Brest Airport

**Brest Fortress

* Brest, Kyustendil Province, Bulgaria

* Břest, Czech Republic

*Brest, France

** Arrondissement of Brest

**Brest Bretagne Airport

** Château de Brest

*Br ...

with five ships of the line, ''Royal Sovereign'', , , , , two frigates and one cutter, , , when a French fleet of twelve sail of the line and fourteen large frigates appeared, commanded by Admiral Villaret Joyeuse. The odds being very greatly against him, he was compelled to order a retreat. But two of his ships were slow and unweatherly and fell behind the rest. The van of the French fleet began to catch the two slower British ships. The rearmost ship, ''Mars'', was caught and suffered severely in her rigging and was in danger of being surrounded by the French. Witnessing this, Cornwallis turned his squadron around to support her. The French admiral made the assumption that Cornwallis must have sighted assistance beyond his own field of vision and had turned to engage the enemy knowing that a superior force was nearby to come to their relief. The French admiral ordered his ships to disengage and Cornwallis and his small squadron retreated in order. The action is remarkable evidence of the moral superiority which the victory of the Glorious First of June

The Glorious First of June (1 June 1794), also known as the Fourth Battle of Ushant, (known in France as the or ) was the first and largest fleet action of the naval conflict between the Kingdom of Great Britain and the First French Republic ...

, and the known efficiency of the British crews, had given to the Royal Navy. The reputation of Cornwallis was amplified and the praise given him was no doubt the greater because he was personally very popular with officers and men.

Court martial

In 1796 Cornwallis incurred acourt-martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

(in consequence of a misunderstanding and apparently some temper on both sides) on the charge of refusing to obey an order from the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

. He was practically acquitted. The substance of the case was that he demurred on the ground of health at being called upon to go to the West Indies, in a small frigate, and without "comfort".

Command of the Channel Fleet

Cornwallis was promoted

Cornwallis was promoted Admiral of the Blue

The Admiral of the Blue was a senior rank of the Royal Navy of the United Kingdom, immediately outranked by the rank Admiral of the White (see order of precedence below). From 1688 to 1805 this rank was in order of precedence third; after 1805 ...

squadron on 14 February 1799, and held the Channel Command for a short interval when Admiral Jervis (Earl St. Vincent) fell ill in 1801. Cornwallis took command once more when Jervis stood down as commander and became first Lord of the Admiralty

The First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible for the di ...

between 1801 and 1804. On 23 April 1804 he advanced to the rank of Admiral of the White.Harrison On 9 November 1805 he was promoted Admiral of the Red

The Admiral of the Red was a senior rank of the Royal Navy of the United Kingdom, immediately outranked by the rank Admiral of the Fleet (see order of precedence below). The rank did not exist prior to 1805, as the admiral commanding the Red ...

. During this time Cornwallis was in charge of protecting the coast of the United Kingdom as Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

was building a large invasion force. Following Admiral Nelson's victory at Trafalgar Trafalgar most often refers to:

* Battle of Trafalgar (1805), fought near Cape Trafalgar, Spain

* Trafalgar Square, a public space and tourist attraction in London, England

It may also refer to:

Music

* ''Trafalgar'' (album), by the Bee Gees

Pl ...

, Cornwallis was removed from his post and Earl St. Vincent took his place.

Honours and politics

In 1796, Cornwallis was promoted toRear-Admiral of Great Britain

The Rear-Admiral of the United Kingdom is a now honorary office generally held by a senior (possibly retired) Royal Navy admiral, though the current incumbent is a retired Royal Marine General. Despite the title, the Rear-Admiral of the Unite ...

, the title becoming Rear-Admiral of the United Kingdom after the Act of Union came into force in 1801, and then in 1814 he was promoted to Vice-Admiral of the United Kingdom

The Vice-Admiral of the United Kingdom is an honorary office generally held by a senior Royal Navy admiral. The title holder is the official deputy to the Lord High Admiral, an honorary (although once operational) office which was vested in th ...

His greatest honours might be considered to be his various nicknames among the sailors, "Billy go tight" (given on account of his rubicund complexion), as well as "Billy Blue", "Coachee", and "Mr Whip". Sailors appear to have only given nicknames to those commanders whom they liked. The various nicknames of Cornwallis seem to show that he was regarded with more of affection than reverence. Cornwallis was also made a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate medieval ceremony for appointing a knight, which involved bathing (as a symbol of purification) as one ...

in 1815.

Cornwallis served as Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

(MP) for Eye during the periods, 1768–1774, 1782–1784, 1790–1800 and, 1801–1807. He also served as MP for Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

from 1782 to 1790.

Later life

Cornwallis never married. In 1800 he leased and later purchased the Newlands estate inMilford on Sea

Milford on Sea, often hyphenated, is a large village or small town and a civil parish on the Hampshire coast. The parish had a population of 4,660 at the 2011 census and is centred about south of Lymington. Tourism and businesses for quite pr ...

in Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial county, ceremonial and non-metropolitan county, non-metropolitan counties of England, county in western South East England on the coast of the English Channel. Home to two major English citi ...

. He was joined by his close friend and fellow naval officer Captain John Whitby and his wife Mary Anna Theresa Whitby. John Whitby died in 1806, but Mary and her infant daughter Theresa

Teresa (also Theresa, Therese; french: Thérèse) is a feminine given name.

It originates in the Iberian Peninsula in late antiquity. Its derivation is uncertain, it may be derived from Greek θερίζω (''therízō'') "to harvest or re ...

stayed on looking after Cornwallis into his old age. On Sir William Cornwallis' death in 1819, Mary Whitby and her daughter inherited his fortune.

References

* Schom, A. (1990). ''Trafalgar: Countdown to battle 1803–1805.'' New York: Atheneum.Bibliography

* ''The naval history of Great Britain from the declaration of war by France in February 1793 to the accession of George IV in January 1820 : with an account of the origin and progressive increase of the British Navy ...'' Five volumes (London Baldwin, Cradock & Joy, 1822–24); New edition in Six volumes '' ... and an account of the Burmese War and the battle of Navarino''. (London: R. Bentley, 1837); (London: R. Bentley, 1847); (London: R. Bentley, 1859); (London: Richard Bentley, 1860); (London: Richard Bentley, 1886); (London: Macmillan, 1902); (London: Conway Maritime Press, 2002). * * * *Dispatches and letters relating to the blockade of Brest, 1803–1805

External links

* * * , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Cornwallis, William 1744 births 1819 deaths Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath Royal Navy admirals British MPs 1768–1774 British MPs 1780–1784 British MPs 1784–1790 British MPs 1790–1796 British MPs 1796–1800 Royal Navy personnel of the American Revolutionary War Royal Navy personnel of the French Revolutionary Wars Royal Navy personnel of the Napoleonic Wars Royal Navy officers who were court-martialled Members of the Parliament of Great Britain for English constituencies Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for English constituencies UK MPs 1801–1802 UK MPs 1802–1806 UK MPs 1806–1807 Younger sons of earlsWilliam

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...