William Bligh on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Vice-Admiral William Bligh (9 September 1754 ŌĆō 7 December 1817) was an officer of the

In 1776, Bligh was selected by

In 1776, Bligh was selected by

Because the vessel was rated only as a cutter, ''Bounty'' had no commissioned officers other than Bligh (who was then only a lieutenant), a very small crew, and no

Because the vessel was rated only as a cutter, ''Bounty'' had no commissioned officers other than Bligh (who was then only a lieutenant), a very small crew, and no  ]Despite being in the majority, none of the loyalists put up a significant struggle once they saw Bligh bound, and the ship was taken over without bloodshed. The mutineers provided Bligh and eighteen loyal crewmen a launch (so heavily loaded that the

]Despite being in the majority, none of the loyalists put up a significant struggle once they saw Bligh bound, and the ship was taken over without bloodshed. The mutineers provided Bligh and eighteen loyal crewmen a launch (so heavily loaded that the  Bligh had confidence in his navigational skills, which he had perfected under the instruction of

Bligh had confidence in his navigational skills, which he had perfected under the instruction of

/ref> The ackee's scientific name ''Blighia sapida'' in

Shortly after Bligh's arrest, a watercolour illustrating the arrest by an unknown artist was exhibited in Sydney at perhaps Australia's first public art exhibition. The watercolour depicts a soldier dragging Bligh from underneath one of the servantsŌĆÖ beds in Government House, with two other figures standing by. The two soldiers in the watercolour are most likely John Sutherland and Michael Marlborough and the other figure on the far right is believed to represent Lieutenant

Shortly after Bligh's arrest, a watercolour illustrating the arrest by an unknown artist was exhibited in Sydney at perhaps Australia's first public art exhibition. The watercolour depicts a soldier dragging Bligh from underneath one of the servantsŌĆÖ beds in Government House, with two other figures standing by. The two soldiers in the watercolour are most likely John Sutherland and Michael Marlborough and the other figure on the far right is believed to represent Lieutenant  Bligh received a letter in January 1810, advising him that the rebellion had been declared illegal, and that the British Foreign Office had declared it to be a mutiny.

Bligh received a letter in January 1810, advising him that the rebellion had been declared illegal, and that the British Foreign Office had declared it to be a mutiny.

Bligh died of cancer in

Bligh died of cancer in

Log of the Proceedings of His Majestys Ship Bounty Lieut. Wm Bligh Commander from Otaheite towards Jamaica, signed `Wm Bligh', 5 Apr. 1789 -13 Mar. 1790

Bligh family papers, principally those of Vice-Admiral William Bligh, were presented to the then Public Library of New South Wales on 29 October 1902 by Bligh's grandson William Russell Bligh. These papers were subsequently transferred from the Public Library to the Mitchell Library in June 1910,

Letter from William Bligh to Rt. Hon. Charles Francis Greville

10 September 1808. 10 September 1808; Autograph letter, signed, written from Government House, Sydney (8 pages). Bligh relates the circumstances of his seizure by the New South Corps on 26 January 1808 and subsequent house arrest, blaming the events on the machinations of John Macarthur,

papers concerning William Bligh

1811, Proceedings of A General Court-Martial held at Chelsea Hospital ... for the Trial of Lieut.-Col. Geo. Johnston ..., London, Sherwood, Neely and Jones, 1811. Dr Vyse's bookplate is pasted on the inside of the front cover. Letter from William Bligh to Rev. Dr Vyse presenting him with the above book, 13 November 1811. The letter is unsigned but is sealed with Bligh's personal seal.

papers relating to Bligh estate, 1838-1840, 1844-1846

Legal documents that pertain to the administration and sale of the estate amassed by William Bligh in New South Wales that include Copenhagen, Camperdown, Mount Betham, Simpson's Farm, and Tyler's Farm,

Letter from William Bligh to Sir Evan Nepean, 24 April 1791

Letter (with transcript) from William Bligh to Sir Evan Nepean referring to preparations for the second breadfruit voyage to Tahiti and the West Indies.

Letter from William Bligh to Sir Joseph Banks, 26 November 1805

letter was written from the Lady Madeleleine Sinclair several months before she sailed for New South Wales,

Papers, 1769-1822, undated, A. HMS Bounty papers, 1787-1794, B. HMS Falcon, Commission, 1790, C. HMS Medea, Commission, 1790, D. HMS Providence and the tender HMS Assistant, papers, 1791-1793, undated, E. HMS Warley, Commission, 1795, F. HMS Calcutta, Commission, 1795, G. HMS Director, papers, 1796, 1797, undated, H. HMS Glatton, papers, 1801, I. HMS Irresistable, Commission, 1801, J. HMS Warrior, Commission, 1804, K. Captain and Governor-in-Chief of the Territory of New South Wales and its dependencies, papers, 1805-1811, undated, L. Naval and Other papers, 1769-1822, undated

Pardon granted to Joseph Moreton by William Bligh, 29 October 1806

1 folder of textual material - manuscript,

A. G. L. Shaw, 'Bligh, William (1754 ŌĆō1817)'

''

Royal Naval Museum, The Mutiny on HMS Bounty

The Extraordinary Life, Times and Travels of Vice-Admiral William Bligh

Multimedia biography with music, sound effects, video, large images and graphics

Portraits of Bligh

in the

Log Of Captain Bligh - Mutiny and Survival

His Day-by-Day personal account of survival in a 23 ft boat. ;Online works *

Log of the Bounty by Lieut. Wm Bligh

5 April 1789 -13 Mar 1790, original logbook covering the mutiny and carried by Bligh on his subsequent boat journey to Timor. * * *

A Narrative Of The Mutiny, On Board His Majesty's Ship Bounty

1790

A Voyage to the South Sea

1792 * * * * * *

Rutter, Owen, Turbulent Journey: A Life of William Bligh, Vice-admiral of the Blue, I. Nicholson and Watson, 1936

Mackaness, George, The Life of Vice-Admiral William Bligh, R.N., F.R.S. By Farrar & Rinehart, 1936

*

Journal on HMS Providence, 1791ŌĆō1793

*William Bligh

Pardon granted to Joseph Moreton by William Bligh, 29 October 1806

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

and a colonial administrator. The mutiny on the HMS ''Bounty'' occurred in 1789 when the ship was under his command; after being set adrift in ''Bounty''s launch by the mutineers, Bligh and his loyal men all reached Timor

Timor is an island at the southern end of Maritime Southeast Asia, in the north of the Timor Sea. The island is East TimorŌĆōIndonesia border, divided between the sovereign states of East Timor on the eastern part and Indonesia on the western p ...

alive, after a journey of . Bligh's logbooks documenting the mutiny were inscribed on the UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

Australian Memory of the World register on 26 February 2021.

Seventeen years after the ''Bounty'' mutiny, on 13 August 1806, he was appointed Governor of New South Wales

The governor of New South Wales is the viceregal representative of the Australian monarch, King Charles III, in the state of New South Wales. In an analogous way to the governor-general of Australia at the national level, the governors of the ...

in Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

, with orders to clean up the corrupt rum

Rum is a liquor made by fermenting and then distilling sugarcane molasses or sugarcane juice. The distillate, a clear liquid, is usually aged in oak barrels. Rum is produced in nearly every sugar-producing region of the world, such as the Ph ...

trade of the New South Wales Corps

The New South Wales Corps (sometimes called The Rum Corps) was formed in England in 1789 as a permanent regiment of the British Army to relieve the New South Wales Marine Corps, who had accompanied the First Fleet to Australia, in fortifying the ...

. His actions directed against the trade resulted in the so-called Rum Rebellion

The Rum Rebellion of 1808 was a ''coup d'├®tat'' in the then-British penal colony of New South Wales, staged by the New South Wales Corps in order to depose Governor William Bligh. Australia's first and only military coup, the name derives fr ...

, during which Bligh was placed under arrest on 26 January 1808 by the New South Wales Corps and deposed from his command, an act which the British Foreign Office

Foreign may refer to:

Government

* Foreign policy, how a country interacts with other countries

* Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in many countries

** Foreign Office, a department of the UK government

** Foreign office and foreign minister

* Unit ...

later declared to be illegal. He died in London on 7 December 1817.

Early life

William Bligh was born on 9 September 1754, but it is not clear where. It is likely that he was born inPlymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymouth ...

, Devon

Devon ( , historically known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South West England. The most populous settlement in Devon is the city of Plymouth, followed by Devon's county town, the city of Exeter. Devon is ...

, as he was baptised at St Andrew's Church on Royal Parade in Plymouth on 4 October 1754, where Bligh's father, Francis (1721ŌĆō1780), was serving as a customs officer. Bligh's ancestral home of Tinten Manor in St Tudy, near Bodmin

Bodmin () is a town and civil parish in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is situated south-west of Bodmin Moor.

The extent of the civil parish corresponds fairly closely to that of the town so is mostly urban in character. It is bordere ...

, Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a historic county and ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people. Cornwall is bordered to the north and west by the Atlantic ...

, is also a possibility. Bligh's mother, Jane Pearce (n├®e Balsam; 1713ŌĆō1768), was a widow who married Francis at the age of 40.

Bligh was signed for the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

at age seven, at a time when it was common to sign on a "young gentleman" simply to gain, or at least record, the experience at sea required for a commission. In 1770, at age 16, he joined HMS ''Hunter'' as an able seaman

An able seaman (AB) is a seaman and member of the deck department of a merchant ship with more than two years' experience at sea and considered "well acquainted with his duty". An AB may work as a watchstander, a day worker, or a combination ...

, the term used because there was no vacancy for a midshipman

A midshipman is an officer of the lowest rank, in the Royal Navy, United States Navy, and many Commonwealth navies. Commonwealth countries which use the rank include Canada (Naval Cadet), Australia, Bangladesh, Namibia, New Zealand, South Afr ...

. He became a midshipman early in the following year. In September 1771, Bligh was transferred to and remained on the ship for three years.

In 1776, Bligh was selected by

In 1776, Bligh was selected by Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

James Cook

James Cook (7 November 1728 Old Style date: 27 October ŌĆō 14 February 1779) was a British explorer, navigator, cartographer, and captain in the British Royal Navy, famous for his three voyages between 1768 and 1779 in the Pacific Ocean an ...

(1728ŌĆō1779), for the position of sailing master

The master, or sailing master, is a historical rank for a naval officer trained in and responsible for the navigation of a sailing vessel. The rank can be equated to a professional seaman and specialist in navigation, rather than as a military ...

of and accompanied Cook in July 1776 on Cook's third voyage to the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

, during which Cook was killed. Bligh played a significant role in navigating the beleaguered expedition back to England in August 1780. He was also able to supply details of Cook's last voyage following the return.

Bligh married Elizabeth Betham, daughter of a customs collector (stationed in Douglas, Isle of Man

Douglas ( gv, Doolish, ) is the capital and largest town of the Isle of Man, with a population of 26,677 (2021). It is located at the mouth of the River Douglas, and on a sweeping bay of . The River Douglas forms part of the town's harbour ...

), on 4 February 1781. The wedding took place at nearby Onchan

Onchan (; glv, Kione Droghad) is a village in the parish of Onchan on the Isle of Man. It is at the north end of Douglas Bay. Administratively a district, it has the second largest population of settlements on the island, after Douglas, with wh ...

.Trevor Kneale, ''The Isle of Man'', Pevensey Island Guides, Brunel House, Newton Abbot, Devon, 2007, . A few days later, he was appointed to serve on HMS ''Belle Poule'' as master (senior warrant officer responsible for navigation). Soon after this, in August 1781, he fought in the Battle of Dogger Bank under Admiral Parker, which won him his commission as a lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often sub ...

. For the next 18 months, he was a lieutenant on various ships. He also fought with Lord Howe at Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

in 1782.

Between 1783 and 1787, Bligh was a captain in the merchant service. Like many lieutenants, he would have found full-pay employment in the Navy; however, commissions were hard to obtain with the fleet largely demobilised at the end of the War with France when that country was allied with the North American rebelling colonies in the War of American Independence

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 ŌĆō September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

(1775ŌĆō1783). In 1787, Bligh was selected as commander of His Majesty's Armed Transport ''Bounty

Bounty or bounties commonly refers to:

* Bounty (reward), an amount of money or other reward offered by an organization for a specific task done with a person or thing

Bounty or bounties may also refer to:

Geography

* Bounty, Saskatchewan, a g ...

''. He rose eventually to the rank of vice admiral in the Royal Navy.

Naval career

William Bligh's naval career involved various appointments and assignments. He first rose to prominence as Master of ''Resolution'', under the command of Captain James Cook. Bligh received praise from Cook during what would be the latter's final voyage. Bligh served on three of the same ships on whichFletcher Christian

Fletcher Christian (25 September 1764 ŌĆō 20 September 1793) was master's mate on board HMS ''Bounty'' during Lieutenant William Bligh's voyage to Tahiti during 1787ŌĆō1789 for breadfruit plants. In the mutiny on the ''Bounty'', Christian sei ...

also served simultaneously in his naval career.

In the early 1780s, while in the merchant service, Bligh became acquainted with a young man named Fletcher Christian

Fletcher Christian (25 September 1764 ŌĆō 20 September 1793) was master's mate on board HMS ''Bounty'' during Lieutenant William Bligh's voyage to Tahiti during 1787ŌĆō1789 for breadfruit plants. In the mutiny on the ''Bounty'', Christian sei ...

(1764ŌĆō1793), who was eager to learn navigation from him. Bligh took Christian under his wing, and the two became friends.

Voyage of ''Bounty''

The mutiny on theRoyal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

vessel HMAV ''Bounty'' occurred in the South Pacific Ocean

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''s┼½├Š'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sun├Šaz ...

on 28 April 1789. Led by Master's Mate

Master's mate is an obsolete rating which was used by the Royal Navy, United States Navy and merchant services in both countries for a senior petty officer who assisted the master. Master's mates evolved into the modern rank of Sub-Lieutenant in t ...

/ Acting Lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often sub ...

Fletcher Christian

Fletcher Christian (25 September 1764 ŌĆō 20 September 1793) was master's mate on board HMS ''Bounty'' during Lieutenant William Bligh's voyage to Tahiti during 1787ŌĆō1789 for breadfruit plants. In the mutiny on the ''Bounty'', Christian sei ...

, disaffected crewmen seized control of the ship, and set the then Lieutenant Bligh, who was the ship's captain, and 18 loyalists adrift in the ship's open launch. The mutineers variously settled on Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian ; ; previously also known as Otaheite) is the largest island of the Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia. It is located in the central part of the Pacific Ocean and the nearest major landmass is Austr ...

or on Pitcairn Island

Pitcairn Island is the only inhabited island of the Pitcairn Islands, of which many inhabitants are descendants of mutineers of HMS ''Bounty''.

Geography

The island is of volcanic origin, with a rugged cliff coastline. Unlike many other ...

. Meanwhile, Bligh completed a voyage of more than 3,500 nautical miles (6,500 km; 4,000 mi) to the west in the launch to reach safety north of Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

in the Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, which ...

(modern Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Guine ...

) and began the process of bringing the mutineers to justice.

First breadfruit voyage

In 1787, Lieutenant Bligh, as he then was, took command of HMAV ''Bounty.'' In order to win a premium offered by theRoyal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

, he first sailed to Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian ; ; previously also known as Otaheite) is the largest island of the Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia. It is located in the central part of the Pacific Ocean and the nearest major landmass is Austr ...

to obtain breadfruit

Breadfruit (''Artocarpus altilis'') is a species of flowering tree in the mulberry and jackfruit family (Moraceae) believed to be a domesticated descendant of ''Artocarpus camansi'' originating in New Guinea, the Maluku Islands, and the Philippi ...

trees, then set course east across the South Pacific for South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the southe ...

and the Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ram├Łrez ...

and eventually to the Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea ( es, Mar Caribe; french: Mer des Cara├»bes; ht, Lanm├© Karayib; jam, Kiaribiyan Sii; nl, Cara├»bische Zee; pap, Laman Karibe) is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean in the tropics of the Western Hemisphere. It is bounded by Mexico ...

, where breadfruit was wanted for experiments to see whether it would be a successful food crop for enslaved Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

ns there on British colonial plantations in the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

islands. According to one modern researcher, the notion that breadfruit had to be collected from Tahiti was intentionally misleading. Tahiti was merely one of many places where the esteemed seedless breadfruit could be found. The real reason for choosing Tahiti has its roots in the territorial contention that existed then between France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

at the time. ''Bounty'' never reached the Caribbean, as mutiny

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military, of a crew or of a crew of pirates) to oppose, change, or overthrow an organization to which they were previously loyal. The term is commonly used for a rebellion among member ...

broke out on board shortly after the ship left Tahiti.

The voyage to Tahiti was difficult. After trying unsuccessfully for a month to go west by rounding South America and Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ram├Łrez ...

, ''Bounty'' was finally defeated by the notoriously stormy weather and opposite winds and forced to take the longer way to the east around the southern tip of Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

(Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperan├¦a is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is t ...

and Cape Agulhas

Cape Agulhas (; pt, Cabo das Agulhas , "Cape of the Needles") is a rocky headland in Western Cape, South Africa.

It is the geographic southern tip of the African continent and the beginning of the dividing line between the Atlantic and Indian ...

). That delay caused a further delay in Tahiti, as Bligh had to wait five months for the breadfruit plants to mature sufficiently to be potted in soil and transported. ''Bounty'' departed Tahiti heading west in April 1789.

Mutiny

Because the vessel was rated only as a cutter, ''Bounty'' had no commissioned officers other than Bligh (who was then only a lieutenant), a very small crew, and no

Because the vessel was rated only as a cutter, ''Bounty'' had no commissioned officers other than Bligh (who was then only a lieutenant), a very small crew, and no Royal Marines

The Corps of Royal Marines (RM), also known as the Royal Marines Commandos, are the UK's special operations capable commando force, amphibious light infantry and also one of the five fighting arms of the Royal Navy. The Corps of Royal Marine ...

to provide protection from hostile natives during stops or to enforce security on board ship. To allow longer uninterrupted sleep, Bligh divided his crew into three watches instead of two, placing his ''prot├®g├®'' Fletcher Christian

Fletcher Christian (25 September 1764 ŌĆō 20 September 1793) was master's mate on board HMS ''Bounty'' during Lieutenant William Bligh's voyage to Tahiti during 1787ŌĆō1789 for breadfruit plants. In the mutiny on the ''Bounty'', Christian sei ...

ŌĆörated as a Master's Mate

Master's mate is an obsolete rating which was used by the Royal Navy, United States Navy and merchant services in both countries for a senior petty officer who assisted the master. Master's mates evolved into the modern rank of Sub-Lieutenant in t ...

ŌĆöin charge of one of the watches. The mutiny

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military, of a crew or of a crew of pirates) to oppose, change, or overthrow an organization to which they were previously loyal. The term is commonly used for a rebellion among member ...

, which took place on 28 April 1789 during the return voyage, was led by Christian and supported by eighteen of the crew. They had seized firearms during Christian's night watch and surprised and bound Bligh in his cabin.

]Despite being in the majority, none of the loyalists put up a significant struggle once they saw Bligh bound, and the ship was taken over without bloodshed. The mutineers provided Bligh and eighteen loyal crewmen a launch (so heavily loaded that the

]Despite being in the majority, none of the loyalists put up a significant struggle once they saw Bligh bound, and the ship was taken over without bloodshed. The mutineers provided Bligh and eighteen loyal crewmen a launch (so heavily loaded that the gunwale

The gunwale () is the top edge of the hull of a ship or boat.

Originally the structure was the "gun wale" on a sailing warship, a horizontal reinforcing band added at and above the level of a gun deck to offset the stresses created by firing ...

s were only a few inches above the water). They were allowed four cutlass

A cutlass is a short, broad sabre or slashing sword, with a straight or slightly curved blade sharpened on the cutting edge, and a hilt often featuring a solid cupped or basket-shaped guard. It was a common naval weapon during the early Age of ...

es, food and water for perhaps a week, a quadrant and a compass, but no charts, or marine chronometer

A marine chronometer is a precision timepiece that is carried on a ship and employed in the determination of the ship's position by celestial navigation. It is used to determine longitude by comparing Greenwich Mean Time (GMT), or in the modern ...

. The gunner William Peckover

William Peckover was a gunner in the Royal Navy and served on several vessels most notably commanded by James Cook and William Bligh.

He was born 17 June 1748, son of Daniel Peckover and Mary Avies in Aynho in the River Cherwell, Cherwell Valley, ...

, brought his pocket watch which was used to regulate time. Most of these were obtained by the clerk, Mr Samuel, who acted with great calm and resolution, despite threats from the mutineers. The launch could not hold all the loyal crew members, so four were detained on ''Bounty'' for their useful skills; they were later released in Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian ; ; previously also known as Otaheite) is the largest island of the Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia. It is located in the central part of the Pacific Ocean and the nearest major landmass is Austr ...

.

Tahiti was upwind from Bligh's initial position, and was the obvious destination of the mutineers. Many of the loyalists claimed to have heard the mutineers cry "Huzzah for Otaheite!" as ''Bounty'' pulled away. Timor

Timor is an island at the southern end of Maritime Southeast Asia, in the north of the Timor Sea. The island is East TimorŌĆōIndonesia border, divided between the sovereign states of East Timor on the eastern part and Indonesia on the western p ...

was the nearest Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

an colonial outpost in the Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, which ...

(modern Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Guine ...

), away. Bligh and his crew first made for Tofua

Tofua is a volcanic island in Tonga. Located in the Ha╩╗apai island group, it is a steep-sided composite cone with a summit caldera. It is part of the highly active Kermadec-Tonga subduction zone and its associated volcanic arc, which extends ...

, only a few leagues distant, to obtain supplies. However, they were attacked by hostile natives and John Norton, a quartermaster, was killed. Fleeing from Tofua, Bligh did not dare to stop at the next islands to the west (the Fiji

Fiji ( , ,; fj, Viti, ; Fiji Hindi: Óż½Óż╝Óż┐Óż£ÓźĆ, ''Fij─½''), officially the Republic of Fiji, is an island country in Melanesia, part of Oceania in the South Pacific Ocean. It lies about north-northeast of New Zealand. Fiji consists ...

islands), as he had only a pair of cutlasses for defence and expected hostile receptions. He did however keep a log entitled "Log of the Proceedings of His Majesty's Ship Bounty Lieut. Wm Bligh Commander from Otaheite towards Jamaica" which he used to record events from 5 April 1789 to 13 March 1790. He also made use of a small notebook to sketch a rough map of his discoveries.

Bligh had confidence in his navigational skills, which he had perfected under the instruction of

Bligh had confidence in his navigational skills, which he had perfected under the instruction of Captain James Cook

James Cook (7 November 1728 Old Style date: 27 October ŌĆō 14 February 1779) was a British explorer, navigator, cartographer, and captain in the British Royal Navy, famous for his three voyages between 1768 and 1779 in the Pacific Ocean and ...

. His first responsibility was to bring his men to safety. Thus, he undertook the seemingly impossible voyage to Timor, the nearest European settlement. Bligh succeeded in reaching Timor after a 47-day voyage, the only casualty being the crewman killed on Tofua. From 4 May until 29 May, when they reached the Great Barrier Reef

The Great Barrier Reef is the world's largest coral reef system composed of over 2,900 individual reefs and 900 islands stretching for over over an area of approximately . The reef is located in the Coral Sea, off the coast of Queensland, ...

north of Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

, the 18 men lived on of bread per day. The weather was often stormy, and they were in constant fear of foundering due to the boat's heavily laden condition. On 29 May they landed on a small island off the coast of Australia, which they named Restoration Island, 29 May 1660 being the date of the restoration of the English monarchy after the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642ŌĆō1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

. Over the next week or more they island-hopped north along the Great Barrier reefŌĆöwhile Bligh, cartographer as always, sketched maps of the coast. Early in June they passed through the Endeavour Strait

The Endeavour Strait is a strait running between the Australian mainland Cape York Peninsula and Prince of Wales Island in the extreme south of the Torres Strait, in northern Queensland, Australia. It was named in 1770 by explorer James Co ...

and sailed again on the open sea until they reached Coupang

Coupang ( ko, ņ┐ĀĒīĪ) is a South Korean e-commerce company based in Seoul, South Korea, and incorporated in Delaware, United States. Founded in 2010 by Bom Kim, the company expanded to become the largest online marketplace in South Korea. It ...

, a settlement on Timor, on 14 June 1789. Three of the men who survived this arduous voyage with him were so weak that they soon died of sickness, possibly malaria, in the pestilential Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, which ...

port of Batavia

Batavia may refer to:

Historical places

* Batavia (region), a land inhabited by the Batavian people during the Roman Empire, today part of the Netherlands

* Batavia, Dutch East Indies, present-day Jakarta, the former capital of the Dutch East In ...

, the present-day Indonesian capital of Jakarta

Jakarta (; , bew, Jakarte), officially the Special Capital Region of Jakarta ( id, Daerah Khusus Ibukota Jakarta) is the capital and largest city of Indonesia. Lying on the northwest coast of Java, the world's most populous island, Jakarta ...

, as they waited for transport to Britain. Two others died on the way to England.

Possible causes of the mutiny

The reasons behind the mutiny are still debated; some sources report that Bligh was a tyrant whose abuse of the crew led them to feel that they had no choice but to take over the ship. Other sources argue that Bligh was no worse (and in many cases gentler) than the average captain and naval officer of the era, and that the crewŌĆöinexperienced and unused to the rigours of the seaŌĆöwere corrupted by the freedom, idleness and sexual licence of their five months in Tahiti, finding themselves unwilling to return to the "Jack Tar

Jack Tar (also Jacktar, Jack-tar or Tar) is a common English language, English term originally used to refer to Sailor, seamen of the British Merchant Navy, Merchant or Royal Navy, particularly during the period of the British Empire. By World War ...

's" life of an ordinary seaman. This view holds that most of the men supported Christian's prideful personal vendetta against Bligh out of a misguided hope that their new captain would return them to Tahiti to live their lives hedonistically and in peace, free from Bligh's acid tongue and strict discipline.

The mutiny is made more mysterious by the friendship of Christian and Bligh, which dates back to Bligh's days in the merchant service. Christian was well acquainted with the Bligh family. As Bligh was being set adrift he appealed to this friendship, saying "you have dandled my children upon your knee". According to Bligh, Christian "appeared disturbed" and replied, "That,ŌĆöCaptain Bligh,ŌĆöthat is the thing;ŌĆöŌĆöI am in hellŌĆöI am in hell".

''Bounty''s log shows that Bligh was relatively sparing in his punishments. He scolded when other captains would have whipped, and whipped when other captains would have hanged. He was an educated man, deeply interested in science, convinced that good diet and sanitation were necessary for the welfare of his crew. He took a great interest in his crew's exercise, was very careful about the quality of their food and insisted upon the ''Bounty'' being kept very clean. The modern historian John Beaglehole

John Cawte Beaglehole (13 June 1901 ŌĆō 10 October 1971) was a New Zealand historian whose greatest scholastic achievement was the editing of James Cook's three journals of exploration, together with the writing of an acclaimed biography of Coo ...

has described the major flaw in this otherwise enlightened naval officer: " ligh madedogmatic judgements which he felt himself entitled to make; he saw fools about him too easily ŌĆ” thin-skinned vanity was his curse through life ŌĆ” lighnever learnt that you do not make friends of men by insulting them." Bligh was also capable of holding intense grudges against those he thought had betrayed him, such as Midshipman Peter Heywood

Peter Heywood (6 June 1772 ŌĆō 10 February 1831) was a British naval officer who was on board during mutiny on the Bounty, the mutiny of 28 April 1789. He was later captured in Tahiti, tried and condemned to death as a mutineer, but subseq ...

and ship's gunner William Peckover

William Peckover was a gunner in the Royal Navy and served on several vessels most notably commanded by James Cook and William Bligh.

He was born 17 June 1748, son of Daniel Peckover and Mary Avies in Aynho in the River Cherwell, Cherwell Valley, ...

; in regard to Heywood, Bligh was convinced that the young man was as guilty as Christian. Bligh's first detailed comments on the mutiny are in a letter to his wife Betsy, in which he names Heywood (a mere boy not yet 16) as "one of the ringleaders", adding: "I have now reason to curse the day I ever knew a Christian or a Heywood or indeed a Manks man. Bligh's later official account to the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

lists Heywood with Christian, Edward Young

Edward Young (c. 3 July 1683 ŌĆō 5 April 1765) was an English poet, best remembered for ''Night-Thoughts'', a series of philosophical writings in blank verse, reflecting his state of mind following several bereavements. It was one of the mos ...

and George Stewart as the mutiny's leaders, describing Heywood as a young man of abilities for whom he had felt a particular regard. To the Heywood family Bligh wrote: "His baseness is beyond all description." Peckover applied for a position as gunner on HMS ''Providence'' (the second breadfruit expedition to Tahiti) but was refused by Bligh. In a letter to Sir Joseph Banks, 17 July 1791 (two weeks before departure), Bligh wrote:

Should Peckover my late Gunner ever trouble you to render him further services I shall esteem it a favour if you will tell him I informed you he was a vicious and worthless fellow ŌĆō He applied to me to render him service & wanted to be appointed Gunner of the Providence but as I had determined never to suffer an officer who was with me in the ''Bounty'' to sail with again, it was for the cause I did not apply for him. Quoting William Bligh to Sir Joseph Banks, 17 July 1791.Bligh's refusal to appoint Peckover was partly due to

Edward Christian

Edward Christian (3 March 1758 – 29 March 1823) was an English judge and law professor. He was the older brother of Fletcher Christian, leader of the mutiny on the ''Bounty''.

Life

Edward Christian was one of the three sons of Charles Ch ...

's polemic testimony against Bligh in an effort to clear his brother

A brother is a man or boy who shares one or more parents with another; a male sibling. The female counterpart is a sister. Although the term typically refers to a familial relationship, it is sometimes used endearingly to refer to non-familia ...

's name. Christian states in his appendix:

In the evidence of Mr. Peckover and Mr. Fryer, it is proved that Mr. Nelson the botanist said, upon hearing the commencement of the mutiny, "We know whose fault this is, or who is to blame, Mr. Fryer, what have we brought upon ourselves?" In addition to this, it ought to be known that Mr. Nelson, in conversation afterwards with an officer (Peckover) at Timor, who was speaking of returning with Captain Bligh if he got another ship, observed, "I am surprized that you should think of going a second time with ligh(using a term of abuse) who has been the cause of all our losses."Popular fiction often confuses Bligh with Edward Edwards of , who was sent on the Royal Navy's expedition to the South Pacific to find the mutineers and bring them to trial. Edwards is often made out to be the cruel man that Hollywood has portrayed. The 14 men from ''Bounty'' who were captured by Edwards's men were confined in a cramped 18ŌĆ▓ ├Ś 11ŌĆ▓ ├Ś 5ŌĆ▓8ŌĆ│ wooden cell on ''Pandora''s quarterdeck. Yet, when ''Pandora'' ran aground on the

Great Barrier Reef

The Great Barrier Reef is the world's largest coral reef system composed of over 2,900 individual reefs and 900 islands stretching for over over an area of approximately . The reef is located in the Coral Sea, off the coast of Queensland, ...

, three prisoners were immediately let out of the prison cell to help at the pumps. Finally, Captain Edwards gave orders to release the other 11 prisoners, to which end Joseph Hodges, the armourer's mate, went into the cell to remove the prisoners' irons. Unfortunately, before he could finish the job, the ship sank. Four of the prisoners and 31 of the crew died during the sinking. More prisoners would likely have perished, had not William Moulter, a bosun's mate, unlocked their cages before jumping off the sinking vessel.

Aftermath

In October 1790, Bligh was honourably acquitted at thecourt-martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

inquiring into the loss of ''Bounty.'' Shortly thereafter, he published ''A Narrative of the Mutiny on board His Majesty's Ship "Bounty"; And the Subsequent Voyage of Part of the Crew, In the Ship's Boat, from Tofoa, one of the Friendly Islands, to Timor, a Dutch Settlement in the East Indies.'' Of the 10 surviving prisoners eventually brought home in spite of ''Pandoras loss, four were acquitted, owing to Bligh's testimony that they were non-mutineers that Bligh was obliged to leave on ''Bounty'' because of lack of space in the launch. Two others were convicted because, while not participating in the mutiny, they were passive and did not resist. They subsequently received royal pardons. One was convicted but excused on a technicality. The remaining three were convicted and hanged.

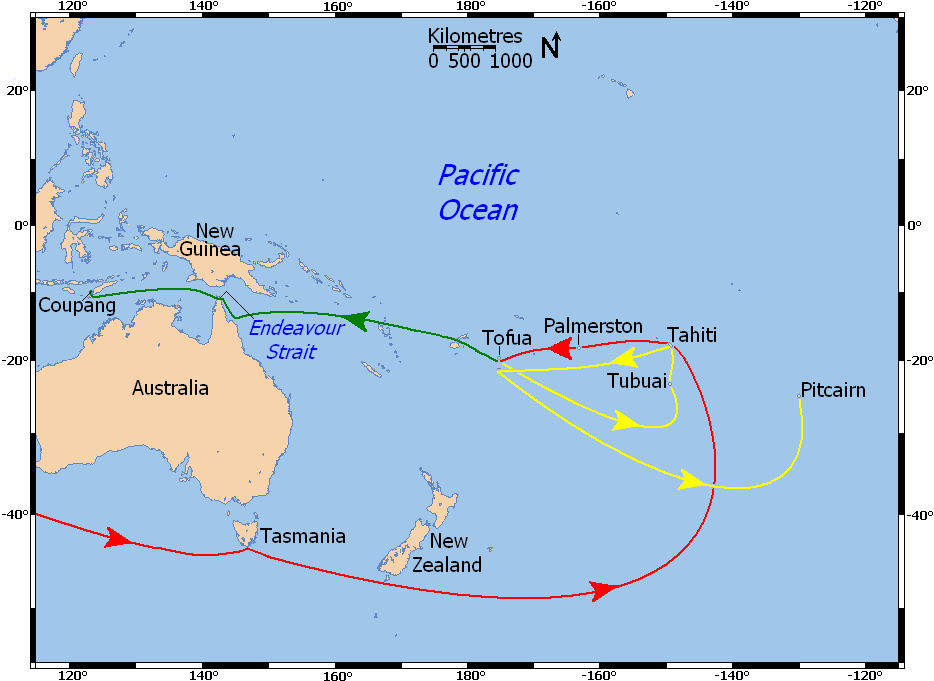

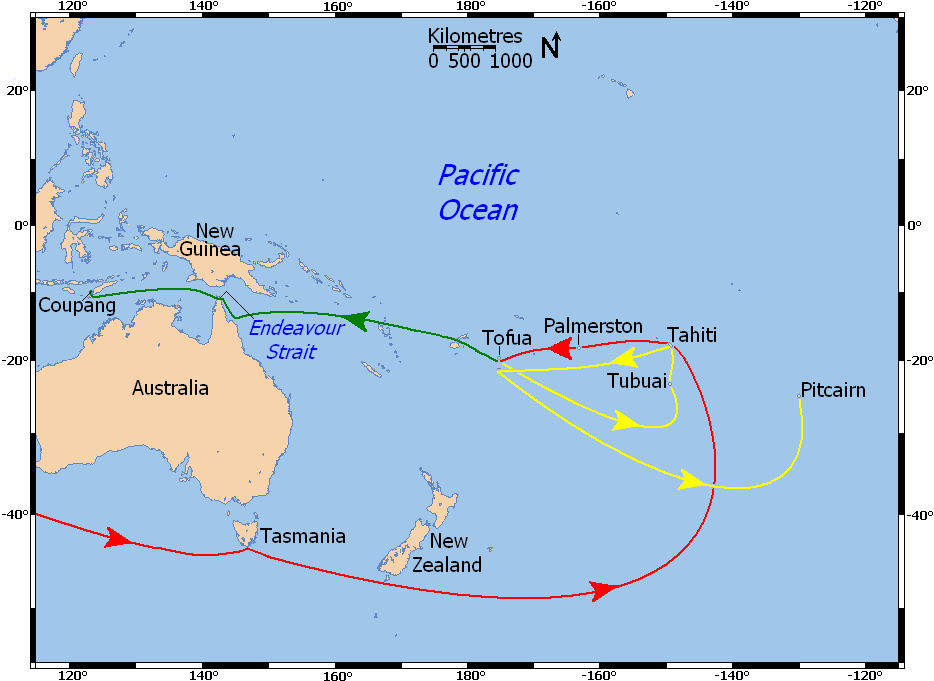

;Comparative travels of ''Bounty'' and the small boat after mutiny:

;Travel up to the mutiny (red):

:1. Tasmania, Adventure Bay (21 August 1788)

:2. first arrival at Tahiti (26 October 1788)

:3. departure for the Caribbean (4 April 1789)

:4. Palmerston

:5. Tofua

:6. 28 April 1789: mutiny

;Travel of the mutineers (yellow):

:7. Tubuai (6 July 1789)

:8. second arrival at Tahiti

:9. Tubuai (16 July 1789)

:10. third arrival at Tahiti (22 September 1789)

:11. departure from Tahiti (23 September 1789)

:12. Tongatapu (15 November 1789)

:13. 15 January 1790: Pitcairn, burning of the Bounty

;Travel of Bligh's boat (green):

:14. Bligh's party set adrift (29 April 1789)

:15. Tonga

:16. Timor (14 June 1789)

;Travel of the mutineers (yellow):

:7. Tubuai (6 July 1789)

:8. second arrival at Tahiti

:9. Tubuai (16 July 1789)

:10. third arrival at Tahiti (22 September 1789)

:11. departure from Tahiti (23 September 1789)

:12. Tongatapu (15 November 1789)

:13. 15 January 1790: Pitcairn, burning of the Bounty

;Travel of Bligh's boat (green):

:14. Bligh's party set adrift (29 April 1789)

:15. Tonga

:16. Timor (14 June 1789)

;Travel of the mutineers (yellow):

:7. Tubuai (6 July 1789)

:8. second arrival at Tahiti

:9. Tubuai (16 July 1789)

:10. third arrival at Tahiti (22 September 1789)

:11. departure from Tahiti (23 September 1789)

:12. Tongatapu (15 November 1789)

:13. 15 January 1790: Pitcairn, burning of the Bounty

;Travel of Bligh's boat (green):

:14. Bligh's party set adrift (29 April 1789)

:15. Tonga

:16. Timor (14 June 1789)

;Travel of the mutineers (yellow):

:7. Tubuai (6 July 1789)

:8. second arrival at Tahiti

:9. Tubuai (16 July 1789)

:10. third arrival at Tahiti (22 September 1789)

:11. departure from Tahiti (23 September 1789)

:12. Tongatapu (15 November 1789)

:13. 15 January 1790: Pitcairn, burning of the Bounty

;Travel of Bligh's boat (green):

:14. Bligh's party set adrift (29 April 1789)

:15. Tonga

:16. Timor (14 June 1789)

Bligh's letter to his wife, Betsy

The following is a letter to Bligh's wife, written fromCoupang

Coupang ( ko, ņ┐ĀĒīĪ) is a South Korean e-commerce company based in Seoul, South Korea, and incorporated in Delaware, United States. Founded in 2010 by Bom Kim, the company expanded to become the largest online marketplace in South Korea. It ...

, Timor

Timor is an island at the southern end of Maritime Southeast Asia, in the north of the Timor Sea. The island is East TimorŌĆōIndonesia border, divided between the sovereign states of East Timor on the eastern part and Indonesia on the western p ...

, Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, which ...

(circa June 1791), in which the first reference to events on the ''Bounty'' is made.

My Dear, Dear Betsy, I am now, for the most part, in a part of the world I never expected, it is however a place that has afforded me relief and saved my life, and I have the happiness to assure you that I am now in perfect health.... Know then my own Dear Betsy, that I have lost the ''Bounty'' ... on the 28 April at day light in the morning Christian having the morning watch. He with several others came into my Cabin while I was a Sleep, and seizing me, holding naked Bayonets at my Breast, tied my Hands behind my back, and threatened instant destruction if I uttered a word. I however call'd loudly for assistance, but the conspiracy was so well laid that the Officers Cabbin Doors were guarded by Centinels, so Nelson, Peckover, Samuels or the Master could not come to me. I was now dragged on Deck in my Shirt & closely guarded ŌĆō I demanded of Christian the case of such a violent act, & severely degraded for his Villainy but he could only answer ŌĆō "not a word sir or you are Dead." I dared him to the act & endeavoured to rally some one to a sense of their duty but to no effect.... The Secrisy of this Mutiny is beyond all conception so that I can not discover that any who are with me had the least knowledge of it. It is unbeknown to me why I must beguile such force. Even Mr. Tom Ellison took such a liking to Otaheite ahitithat he also turned Pirate, so that I have been run down by my own Dogs... My misfortune I trust will be properly considered by all the World ŌĆō It was a circumstance I could not foresee ŌĆō I had not sufficient Officers & had they granted me Marines most likely the affair would never have happened ŌĆō I had not a Spirited & brave fellow about me & the Mutineers treated them as such. My conduct has been free of blame, & I showed everyone that, tied as I was, I defied every Villain to hurt me... I know how shocked you will be at this affair but I request of you My Dear Betsy to think nothing of it all is now past & we will again looked forward to future happyness. Nothing but true consciousness as an Officer that I have done well could support me....Give my blessings to my Dear Harriet, my Dear Mary, my Dear Betsy & to my Dear little stranger & tell them I shall soon be home...To You my Love I give all that an affectionate Husband can give ŌĆō Love, Respect & all that is or ever will be in the power of yourStrictly speaking, the crime of the mutineers (apart from the disciplinary crime of

ever affectionate Friend and Husband Wm Bligh.

mutiny

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military, of a crew or of a crew of pirates) to oppose, change, or overthrow an organization to which they were previously loyal. The term is commonly used for a rebellion among member ...

) was not piracy but barratry, the misappropriation, by those entrusted with its care, of a ship and/or its contents to the detriment of the owner (in this case the British Crown

The Crown is the state (polity), state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, British Overseas Territories, overseas territories, Provinces and territorie ...

).

Second breadfruit voyage

After his exoneration by thecourt-martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

inquiry

An inquiry (also spelled as enquiry in British English) is any process that has the aim of augmenting knowledge, resolving doubt, or solving a problem. A theory of inquiry is an account of the various types of inquiry and a treatment of the ...

into the loss of ''Bounty'', Bligh remained in the Royal Navy. From 1791 to 1793, as master and commander of and in company with under the command of Nathaniel Portlock

Nathaniel Portlock (c. 1748 ŌĆō 12 September 1817) was a British ship's captain, maritime fur trader, and author.

He entered the Royal Navy in 1772 as an able seaman, serving in . In 1776 he joined as master's mate and served on the third Pac ...

, he undertook again to transport breadfruit

Breadfruit (''Artocarpus altilis'') is a species of flowering tree in the mulberry and jackfruit family (Moraceae) believed to be a domesticated descendant of ''Artocarpus camansi'' originating in New Guinea, the Maluku Islands, and the Philippi ...

from Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian ; ; previously also known as Otaheite) is the largest island of the Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia. It is located in the central part of the Pacific Ocean and the nearest major landmass is Austr ...

to the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

. He also transported plants provided by Hugh Ronalds

Hugh Ronalds (4 March 1760 ŌĆō 18 November 1833) was an esteemed nurseryman and horticulturalist in Brentford, who published ''Pyrus Malus Brentfordiensis: or, a Concise Description of Selected Apples'' (1831). His plants were some of the first E ...

, a nurseryman in Brentford

Brentford is a suburban town in West London, England and part of the London Borough of Hounslow. It lies at the confluence of the River Brent and the Thames, west of Charing Cross.

Its economy has diverse company headquarters buildings whi ...

. The operation was generally successful but its immediate objective, which was to provide a cheap and nutritious food for the Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

n slaves in the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

islands around the Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea ( es, Mar Caribe; french: Mer des Cara├»bes; ht, Lanm├© Karayib; jam, Kiaribiyan Sii; nl, Cara├»bische Zee; pap, Laman Karibe) is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean in the tropics of the Western Hemisphere. It is bounded by Mexico ...

was not met, as most slaves refused to eat the new food. During this voyage, Bligh also collected samples of the ackee fruit of Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

, introducing it to the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

in Britain upon his return.Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew: Information Sheets: Staple Foods II ŌĆō Fruits/ref> The ackee's scientific name ''Blighia sapida'' in

binomial nomenclature

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called nomenclature ("two-name naming system") or binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, bot ...

was given in honour of Bligh.

In Adventure Bay, Tasmania

Adventure Bay is the name of a locality, a township and a geographical feature on the eastern side of Bruny Island, Tasmania. At the , Adventure Bay had a population of 218.

Early history

The first European to sight the bay was explorer Abel ...

, third lieutenant George Tobin

George Tobin is an American musical artist and record producer who has produced albums for a long list of musical artists including Robert John, Smokey Robinson, Kim Carnes, Kicking Harold, and PC Quest. He is best known, however, for discove ...

made the first European drawing of an echidna

Echidnas (), sometimes known as spiny anteaters, are quill-covered monotremes (egg-laying mammals) belonging to the family Tachyglossidae . The four extant species of echidnas and the platypus are the only living mammals that lay eggs and the ...

.

Subsequent career and the Rum Rebellion

In February 1797, while Bligh was captain of , he surveyed theRiver Humber

The Humber is a large tidal estuary on the east coast of Northern England. It is formed at Trent Falls, Faxfleet, by the confluence of the tidal rivers Ouse and Trent. From there to the North Sea, it forms part of the boundary between the ...

, preparing a map of the stretch from Spurn

Spurn is a narrow sand tidal island located off the tip of the coast of the East Riding of Yorkshire, England that reaches into the North Sea and forms the north bank of the mouth of the Humber Estuary. It was a spit with a semi-permanent co ...

to the west of Sunk Island.

In AprilŌĆōMay, Bligh was one of the captains whose crews mutinied over "issues of pay and involuntary service for common seamen" during the Nore mutiny

The Spithead and Nore mutinies were two major mutinies by sailors of the Royal Navy in 1797. They were the first in an increasing series of outbreaks of maritime radicalism in the Atlantic World. Despite their temporal proximity, the mutinies d ...

. The mutiny was not triggered by any specific actions by Bligh; the mutinies "were widespread, ndinvolved a fair number of English ships". Whilst ''Directors role was relatively minor in this mutiny, she was the last to raise the white flag at its cessation. It was at this time that he learned "that his common nickname among men in the fleet was 'that Bounty bastard'."

As captain of ''Director'' at the Battle of Camperdown

The Battle of Camperdown (known in Dutch as the ''Zeeslag bij Kamperduin'') was a major naval action fought on 11 October 1797, between the British North Sea Fleet under Admiral Adam Duncan and a Batavian Navy (Dutch) fleet under Vice-Admiral ...

on 11 October, Bligh engaged three Dutch vessels: ''Haarlem'', ''Alkmaar'' and ''Vrijheid''. While the Dutch suffered serious casualties, only seven seamen were wounded on ''Director''. ''Director'' captured ''Vrijheid'' and the Dutch commander, Vice-Admiral Jan de Winter

Jan Willem de Winter (French: Jean Guillaume de Winter, 23 March 1761 ŌĆō 2 June 1812) was a Dutch admiral during the Napoleonic Wars.

Biography

Early life

De Winter was born in Kampen and entered naval service at a young age. He disting ...

.

Bligh went on to serve under Admiral Nelson

Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronte (29 September 1758 ŌĆō 21 October 1805) was a British flag officer in the Royal Navy. His inspirational leadership, grasp of strategy, and unconventional tactics brought abo ...

at the Battle of Copenhagen on 2 April 1801, in command of , a 56-gun ship of the line

A ship of the line was a type of naval warship constructed during the Age of Sail from the 17th century to the mid-19th century. The ship of the line was designed for the naval tactic known as the line of battle, which depended on the two colu ...

, which was experimentally fitted exclusively with carronades. After the battle, Nelson personally praised Bligh for his contribution to the victory. He sailed ''Glatton'' safely between the banks while three other vessels ran aground. When Nelson pretended not to notice Admiral Parker's signal "43" (stop the battle) and kept the signal "16" hoisted to continue the engagement, Bligh was the only captain in the squadron who could see that the two signals were in conflict. By choosing to fly Nelson's signal, he ensured that all the vessels behind him kept fighting.

Bligh had gained a reputation as a firm disciplinarian. Accordingly, he was offered the position of Governor of New South Wales

The governor of New South Wales is the viceregal representative of the Australian monarch, King Charles III, in the state of New South Wales. In an analogous way to the governor-general of Australia at the national level, the governors of the ...

on the recommendation of Sir Joseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, (19 June 1820) was an English naturalist, botanist, and patron of the natural sciences.

Banks made his name on the 1766 natural-history expedition to Newfoundland and Labrador. He took part in Captain James ...

(President of the Royal Society and a main sponsor of the breadfruit expeditions) and appointed in March 1805, at ┬Ż2,000 per annum, twice the pay of the retiring governor, Philip Gidley King

Captain Philip Gidley King (23 April 1758 ŌĆō 3 September 1808) was a British politician who was the third Governor of New South Wales.

When the First Fleet arrived in January 1788, King was detailed to colonise Norfolk Island for defence an ...

. He arrived in Sydney on 6 August 1806, to become the fourth governor. As his wife Elizabeth had been unwilling to undertake a long sea voyage, Bligh was accompanied by his daughter, Mary Putland

Mary Bligh, Lady O'Connell (later Putland and later O'Connell) (1783ŌĆō1864) was the Lady of Government House, New South Wales, Australia during the period her father William Bligh was the Governor of New South Wales.

Early life

Mary Bligh was ...

, who would be the Lady of Government House; Mary's husband John Putland was appointed as William Bligh's aide-de-camp. During his time in Sydney, his confrontational administrative style provoked the wrath of a number of influential settlers and officials. They included the wealthy landowner and businessman John Macarthur, and prominent Crown representatives such as the colony's principal surgeon, Thomas Jamison

Thomas Jamison ( ŌĆō 25 January 1811) was a naval surgeon, who was surgeon mate on as part First Fleet which founded Colony of New South Wales in 1788. He was surgeon at the Norfolk Island settlement, before returning to Sydney and becoming pr ...

, as well as senior officers of the New South Wales Corps

The New South Wales Corps (sometimes called The Rum Corps) was formed in England in 1789 as a permanent regiment of the British Army to relieve the New South Wales Marine Corps, who had accompanied the First Fleet to Australia, in fortifying the ...

. Jamison and his military associates were defying government regulations by engaging in private trading ventures for profit, a practice which Bligh was determined to put a stop to.

The conflict between Bligh and the entrenched colonists culminated in another mutiny, the Rum Rebellion

The Rum Rebellion of 1808 was a ''coup d'├®tat'' in the then-British penal colony of New South Wales, staged by the New South Wales Corps in order to depose Governor William Bligh. Australia's first and only military coup, the name derives fr ...

, when, on 26 January 1808, 400 soldiers of the New South Wales Corps under the command of Major George Johnston marched on Government House

Government House is the name of many of the official residences of governors-general, governors and lieutenant-governors in the Commonwealth and the remaining colonies of the British Empire. The name is also used in some other countries.

Gover ...

in Sydney to arrest Bligh. A petition written by John Macarthur and addressed to George Johnston was written the day of the arrest but most of the 151 signatures were gathered in the days after Bligh's overthrow. A rebel government was subsequently installed and Bligh, now deposed, made for Hobart

Hobart ( ; Nuennonne/Palawa kani: ''nipaluna'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian island state of Tasmania. Home to almost half of all Tasmanians, it is the least-populated Australian state capital city, and second-small ...

in Tasmania aboard . Bligh failed to gain support from the authorities in Hobart to retake control of New South Wales, and remained effectively imprisoned on the ''Porpoise'' from 1808 until January 1810.

Shortly after Bligh's arrest, a watercolour illustrating the arrest by an unknown artist was exhibited in Sydney at perhaps Australia's first public art exhibition. The watercolour depicts a soldier dragging Bligh from underneath one of the servantsŌĆÖ beds in Government House, with two other figures standing by. The two soldiers in the watercolour are most likely John Sutherland and Michael Marlborough and the other figure on the far right is believed to represent Lieutenant

Shortly after Bligh's arrest, a watercolour illustrating the arrest by an unknown artist was exhibited in Sydney at perhaps Australia's first public art exhibition. The watercolour depicts a soldier dragging Bligh from underneath one of the servantsŌĆÖ beds in Government House, with two other figures standing by. The two soldiers in the watercolour are most likely John Sutherland and Michael Marlborough and the other figure on the far right is believed to represent Lieutenant William Minchin

William Minchin (1774ŌĆō26 March 1821) was an Irish-born British army officer.

He was commissioned an ensign in the New South Wales Corps on 2 March 1797.

He returned to England with the New South Wales Corps, now the 102nd Regiment of Foot, ...

. This cartoon is Australia's earliest surviving political cartoon and like all political cartoons it makes use of caricature and exaggeration to convey its message. The New South Wales Corps' officers regarded themselves as gentlemen, and in depicting Bligh as a coward, the cartoon declares that Bligh was not a gentleman and therefore not fit to govern.

Of interest, however, was Bligh's concern for the more recently arrived settlers in the colony, who did not have the wealth and influence of Macarthur and Jamison. From the tombstones in Ebenezer and Richmond cemeteries (areas being settled west of Sydney during Bligh's tenure as governor), can be seen the number of boys born around 1807 to 1811 who received "William Bligh" as a given name

A given name (also known as a forename or first name) is the part of a personal name quoted in that identifies a person, potentially with a middle name as well, and differentiates that person from the other members of a group (typically a fa ...

, e.g. William Bligh Turnbull b. 8 June 1809 at Windsor, ancestor of Malcolm Bligh Turnbull, Prime Minister of Australia

The prime minister of Australia is the head of government of the Commonwealth of Australia. The prime minister heads the executive branch of the Australian Government, federal government of Australia and is also accountable to Parliament of A ...

; and James Bligh Johnston, b.1809 at Ebenezer, son of Andrew Johnston, who designed Ebenezer Chapel, Australia's oldest extant church and oldest extant school.

Bligh received a letter in January 1810, advising him that the rebellion had been declared illegal, and that the British Foreign Office had declared it to be a mutiny.

Bligh received a letter in January 1810, advising him that the rebellion had been declared illegal, and that the British Foreign Office had declared it to be a mutiny. Lachlan Macquarie

Major-general (United Kingdom), Major General Lachlan Macquarie, Companion of the Order of the Bath, CB (; gd, Lachann MacGuaire; 31 January 1762 ŌĆō 1 July 1824) was a British Army officer and colonial administrator from Scotland. Macquarie se ...

had been appointed to replace him as governor. At this news Bligh sailed from Hobart. He arrived in Sydney on 17 January 1810, only two weeks into Macquarie's tenure. There he would collect evidence for the coming court martial in England of Major Johnston. He departed to attend the trial on 12 May 1810, arriving on 25 October 1810. In the days immediately prior to their departure, his daughter, Mary Putland (widowed in 1808), was hastily married to the new Lieutenant-Governor, Maurice Charles O'Connell

Sir Maurice Charles Philip O'Connell KCH (1768 ŌĆō 25 May 1848) was a commander of forces and lieutenant-governor of colonial New South Wales.

Early life

Maurice Charles O'Connell was born in Ireland in 1768. He had had a distinguished career ...

, and remained in Sydney. The following year, the trial's presiding officers sentenced Johnston to be cashiered

Cashiering (or degradation ceremony), generally within military forces, is a ritual dismissal of an individual from some position of responsibility for a breach of discipline.

Etymology

From the Flemish (to dismiss from service; to discard ...

, a form of disgraceful dismissal that entailed surrendering his commission in the Royal Marines

The Corps of Royal Marines (RM), also known as the Royal Marines Commandos, are the UK's special operations capable commando force, amphibious light infantry and also one of the five fighting arms of the Royal Navy. The Corps of Royal Marine ...

without compensation. (This was a comparatively mild punishment which enabled Johnston to return a free man to New South Wales, where he could continue to enjoy the benefits of his accumulated private wealth.) Bligh was court martialled twice again during his career, being acquitted both times. Soon after Johnston's trial had concluded, Bligh received a backdated promotion to rear admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star "admiral" rank. It is often regarde ...

. In 1814 he was promoted again to vice admiral of the blue. Perhaps significantly, he never again received an important command, though with the Napoleonic Wars almost over there would have been few fleet commands available.

Bligh was recruited to chart and map Dublin Bay

Dublin Bay ( ga, Cuan Bhaile ├ütha Cliath) is a C-shaped inlet of the Irish Sea on the east coast of Ireland. The bay is about 10 kilometres wide along its northŌĆōsouth base, and 7 km in length to its apex at the centre of the city of Dub ...

, and recommended the building walls for a refuge harbour at what was then known as Dunleary; the large harbour and naval base subsequently built there between 1816 and 1821 was called Kingstown, later renamed D├║n Laoghaire

D├║n Laoghaire ( , ) is a suburban coastal town in Dublin in Ireland. It is the administrative centre of D├║n LaoghaireŌĆōRathdown.

The town was built following the 1816 legislation that allowed the building of a major port to serve Dubli ...

. Many sources claim that Bligh designed the North Bull Wall at the mouth of the River Liffey

The River Liffey (Irish: ''An Life'', historically ''An Ruirthe(a)ch'') is a river in eastern Ireland that ultimately flows through the centre of Dublin to its mouth within Dublin Bay. Its major tributaries include the River Dodder, the River ...

in Dublin. He did propose the construction of a sea wall or barrier at the north of the bay clear a sandbar by Venturi action, but his design was not used. The wall which was constructed used a design by George Halpin

George Halpin (Sr.) (1779? ŌĆō 8 July 1854), was a prominent civil engineer and lighthouse builder, responsible for the construction of much of the Port of Dublin, several of Dublin's bridges, and a number of lighthouses; he is considered the f ...

and resulted in the formation of North Bull Island

Bull Island (Irish: ''Oile├Īn an Tairbh''), more properly North Bull Island (Irish: ''Oile├Īn an Tairbh Thuaidh''), is an island located in Dublin Bay in Ireland, about 5 km long and 800 m wide, lying roughly parallel to the shore off C ...

by the sand cleared by the river's now more narrowly focused force.

Death

Bligh died of cancer in

Bligh died of cancer in Bond Street

Bond Street in the West End of London links Piccadilly in the south to Oxford Street in the north. Since the 18th century the street has housed many prestigious and upmarket fashion retailers. The southern section is Old Bond Street and the l ...

, London, on 7 December 1817 and was buried in a family plot at St. Mary's, Lambeth

Lambeth () is a district in South London, England, in the London Borough of Lambeth, historically in the County of Surrey. It is situated south of Charing Cross. The population of the London Borough of Lambeth was 303,086 in 2011. The area expe ...

(this church is now the Garden Museum

The Garden Museum (formerly known as the Museum of Garden History) in London is Britain's only museum of the art, history and design of gardens. The museum re-opened in 2017 after an 18-month redevelopment project.

The building is largely the ...

). His tomb was notable for its use of Coade stone (''Lithodipyra)'', a compound of clay and other materials which was moulded in imitation of carved stonework and fired in a kiln. This stoneware was produced by Eleanor Coade at her factory in Lambeth. The tomb is topped by an eternal flame, not a breadfruit. A plaque marks Bligh's house, one block east of the Garden Museum at 100 Lambeth Road, near the Imperial War Museum

Imperial War Museums (IWM) is a British national museum organisation with branches at five locations in England, three of which are in London. Founded as the Imperial War Museum in 1917, the museum was intended to record the civil and military ...

.

He was related to Admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet, ...

Sir Richard Rodney Bligh and Captain George Miller Bligh

Captain George Miller Bligh (1780ŌĆō1834) was an officer of the Royal Navy, who saw service during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, eventually rising to the rank of Captain. He was present aboard at the Battle of Trafalgar, and was ...

, and his British and Australian descendants include Native Police

Australian native police units, consisting of Aboriginal troopers under the command (usually) of at least one white officer, existed in various forms in all Australian mainland colonies during the nineteenth and, in some cases, into the twentie ...

Commandant John O'Connell Bligh and the former Premier of Queensland

The premier of Queensland is the head of government in the Australian state of Queensland.

By convention the premier is the leader of the party with a parliamentary majority in the unicameral Legislative Assembly of Queensland. The premier is ap ...

, Anna Bligh

Anna Maria Bligh (born 14 July 1960) is a lobbyist and former Australian politician who served as the 37th Premier of Queensland, in office from 2007 to 2012 as leader of the Labor Party. She was the first woman to hold either position. In 2 ...

. He was also distantly related to the architect and psychical researcher Frederick Bligh Bond

Frederick Bligh Bond (30 June 1864 ŌĆō 8 March 1945), generally known by his second given name ''Bligh'', was an English architect, illustrator, archaeologist and psychical researcher.

Early life

Bligh Bond was the son of the Rev. Frederick ...

.

The suburb Bligh Park in New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

is named after William Bligh as at the time of the Rum Rebellion

The Rum Rebellion of 1808 was a ''coup d'├®tat'' in the then-British penal colony of New South Wales, staged by the New South Wales Corps in order to depose Governor William Bligh. Australia's first and only military coup, the name derives fr ...

the Hawkesbury settlers supported the then-deposed governor.

In literature and film

Bligh is humorously portrayed in SirArthur Quiller-Couch

Sir Arthur Thomas Quiller-Couch (; 21 November 186312 May 1944) was a British writer who published using the pseudonym Q. Although a prolific novelist, he is remembered mainly for the monumental publication '' The Oxford Book of English Verse 1 ...

's short story "Frenchman's Creek" as a competent but irascible and tactless surveyor sent to a small fishing village in Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a historic county and ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people. Cornwall is bordered to the north and west by the Atlantic ...

during the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803ŌĆō1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

. His accent and strong language being misunderstood by the locals as French, he is temporarily imprisoned as a spy.

The situation in Sydney in 1810, with Bligh returning from Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

to be restored as governor, is the setting of Naomi Novik