Wilhelm Frick on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

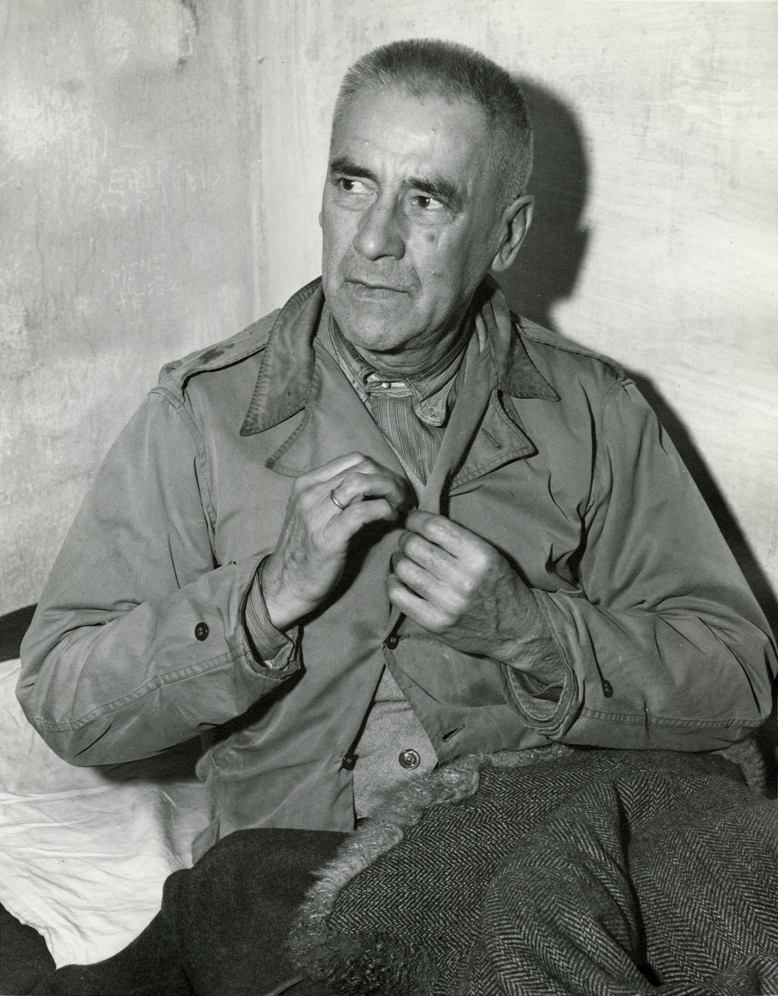

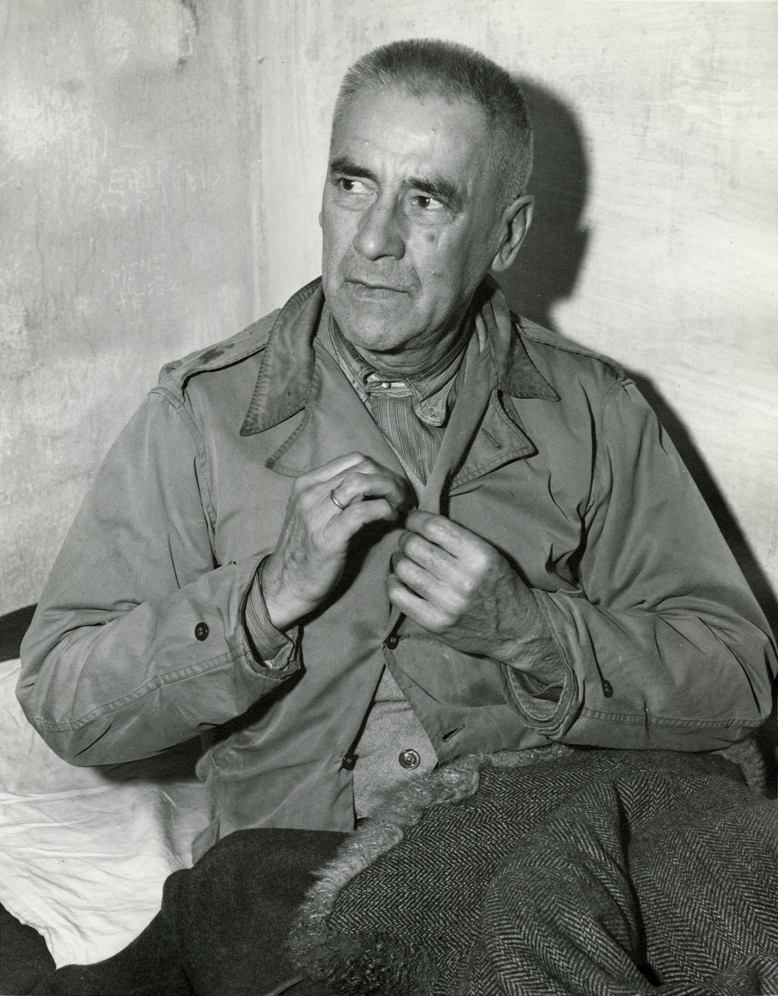

Wilhelm Frick (12 March 1877 – 16 October 1946) was a prominent German politician of the

When Reich president

When Reich president  Frick was instrumental in the

Frick was instrumental in the

Frick was arrested, and was arraigned at the

Frick was arrested, and was arraigned at the

Sautter, ''Wilhelm Frick: Der Legalist des Unrechtsstaates: Eine politische Biographie'', Canadian Journal of History, April 1993

Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

(NSDAP), who served as Reich

''Reich'' (; ) is a German language, German noun whose meaning is analogous to the meaning of the English word "realm"; this is not to be confused with the German adjective "reich" which means "rich". The terms ' (literally the "realm of an emp ...

Minister of the Interior in Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

's cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filing ...

from 1933 to 1943 and as the last governor of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia; cs, Protektorát Čechy a Morava; its territory was called by the Nazis ("the rest of Czechia"). was a partially annexed territory of Nazi Germany established on 16 March 1939 following the German oc ...

.

As the head of the ''Kriminalpolizei

''Kriminalpolizei'' (, "criminal police") is the standard term for the criminal investigation agency within the police forces of Germany, Austria, and the German-speaking cantons of Switzerland. In Nazi Germany, the Kripo was the criminal polic ...

'' (criminal police) in Munich, Frick took part in Hitler's failed Beer Hall Putsch

The Beer Hall Putsch, also known as the Munich Putsch,Dan Moorhouse, ed schoolshistory.org.uk, accessed 2008-05-31.Known in German as the or was a failed coup d'état by Nazi Party ( or NSDAP) leader Adolf Hitler, Erich Ludendorff and othe ...

of 1923, for which he was convicted of high treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

. He managed to avoid imprisonment and soon afterwards became a leading figure of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in the Reichstag. After Hitler became Chancellor of Germany

The chancellor of Germany, officially the federal chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany,; often shortened to ''Bundeskanzler''/''Bundeskanzlerin'', / is the head of the federal government of Germany and the commander in chief of the Ge ...

in 1933, Frick joined the new government and was named Reich Minister of the Interior. Additionally, on 21 May 1935, Frick was named ''Generalbevollmächtigter für die Reichsverwaltung'' (General Plenipotentiary for the Reich Administration). He was instrumental in formulating laws that consolidated the Nazi regime (''Gleichschaltung

The Nazi term () or "coordination" was the process of Nazification by which Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party successively established a system of totalitarian control and coordination over all aspects of German society and societies occupied b ...

''), as well as laws that defined the Nazi racial policy

The racial policy of Nazi Germany was a set of policies and laws implemented in Nazi Germany under the dictatorship of Adolf Hitler, based on a specific racist doctrine asserting the superiority of the Aryan race, which claimed scientific legi ...

, most notoriously the Nuremberg Laws

The Nuremberg Laws (german: link=no, Nürnberger Gesetze, ) were antisemitic and racist laws that were enacted in Nazi Germany on 15 September 1935, at a special meeting of the Reichstag convened during the annual Nuremberg Rally of ...

. On 30 August 1939, immediately prior to the outbreak of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, Frick was appointed by Hitler to the six-person Council of Ministers for Defense of the Reich

The Council of Ministers for the Defense of the Reich (German language, German: ''Ministerrat für die Reichsverteidigung'') was a six-member ministerial council created in Nazi Germany by Adolf Hitler on 30 August 1939, in anticipation of the inva ...

which operated as a war cabinet. Following the rise of the SS, Frick gradually lost favour within the party, and in 1943 he was replaced by Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was of the (Protection Squadron; SS), and a leading member of the Nazi Party of Germany. Himmler was one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany and a main architect of th ...

as interior minister. Frick remained in the cabinet as a minister without portfolio until Hitler's death in 1945.

After World War II, Frick was tried and convicted of war crimes at the Nuremberg trials

The Nuremberg trials were held by the Allies of World War II, Allies against representatives of the defeated Nazi Germany, for plotting and carrying out invasions of other countries, and other crimes, in World War II.

Between 1939 and 1945 ...

and executed

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

by hanging

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a noose or ligature around the neck.Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Hanging as method of execution is unknown, as method of suicide from 1325. The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' states that hanging i ...

.

Early life

Born in the Palatinate municipality of Alsenz, then part of theKingdom of Bavaria

The Kingdom of Bavaria (german: Königreich Bayern; ; spelled ''Baiern'' until 1825) was a German state that succeeded the former Electorate of Bavaria in 1805 and continued to exist until 1918. With the unification of Germany into the German E ...

, Germany, the last of four children of Protestant teacher Wilhelm Frick sen. (d. 1918) and his wife Henriette (née Schmidt). He attended the gymnasium in Kaiserslautern

Kaiserslautern (; Palatinate German: ''Lautre'') is a city in southwest Germany, located in the state of Rhineland-Palatinate at the edge of the Palatinate Forest. The historic centre dates to the 9th century. It is from Paris, from Frankfur ...

, passing his Abitur

''Abitur'' (), often shortened colloquially to ''Abi'', is a qualification granted at the end of secondary education in Germany. It is conferred on students who pass their final exams at the end of ISCED 3, usually after twelve or thirteen year ...

exams in 1896. He went on studying philology

Philology () is the study of language in oral and writing, written historical sources; it is the intersection of textual criticism, literary criticism, history, and linguistics (with especially strong ties to etymology). Philology is also defin ...

at the University of Munich

The Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich (simply University of Munich or LMU; german: Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München) is a public research university in Munich, Germany. It is Germany's List of universities in Germany, sixth-oldest u ...

, but soon after turned to study law in Heidelberg

Heidelberg (; Palatine German language, Palatine German: ''Heidlberg'') is a city in the States of Germany, German state of Baden-Württemberg, situated on the river Neckar in south-west Germany. As of the 2016 census, its population was 159,914 ...

and Humboldt University of Berlin

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (german: Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, abbreviated HU Berlin) is a German public research university in the central borough of Mitte in Berlin. It was established by Frederick William III on the initiative o ...

from 1900, he joined the Bavarian civil service in 1903, working as an attorney at the Munich Police Department. He was appointed a ''Bezirksamtassessor'' in Pirmasens

Pirmasens (; pfl, Bärmesens (also ''Bermesens'' or ''Bärmasens'')) is an independent town in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany, near the border with France. It was famous for the manufacture of shoes. The surrounding rural district was called ''Lan ...

in 1907 and became acting district executive in 1914. Rejected as unfit, Frick did not serve in World War I. He was promoted to the official rank of a ''Regierungsassessor'' and, at his own request, re-assumed his post at the Munich Police Department in 1917.

On 25 April 1910, Frick married Elisabetha Emilie Nagel (1890–1978) in Pirmasens. They had two sons and a daughter. The marriage ended in an ugly divorce in 1934. A few weeks later, on 12 March, Frick remarried in Münchberg Margarete Schultze-Naumburg (1896–1960), the former wife of the Nazi Reichstag MP Paul Schultze-Naumburg

Paul Schultze-Naumburg (10 June 1869 – 19 May 1949) was a German traditionalist architect, painter, publicist and author. A leading critic of modern architecture, he joined the NSDAP in 1930 (aged 61) and became an important advocate of N ...

. Margarete gave birth to a son and a daughter.

Nazi career

In Munich, Frick witnessed the end of the war and the German Revolution of 1918–1919. He sympathized with ''Freikorps

(, "Free Corps" or "Volunteer Corps") were irregular German and other European military volunteer units, or paramilitary, that existed from the 18th to the early 20th centuries. They effectively fought as mercenary or private armies, regar ...

'' paramilitary units fighting against the Bavarian government of Premier Kurt Eisner

Kurt Eisner (; 14 May 1867 21 February 1919)"Kurt Eisner – Encyclopædia Britannica" (biography), ''Encyclopædia Britannica'', 2006, Britannica.com webpageBritannica-KurtEisner. was a German politician, revolutionary, journalist, and theatre c ...

. Chief of Police Ernst Pöhner introduced him to Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

, whom he helped willingly with obtaining permissions to hold political rallies and demonstrations.

Elevated to the rank of an ''Oberamtmann'' and head of the ''Kriminalpolizei

''Kriminalpolizei'' (, "criminal police") is the standard term for the criminal investigation agency within the police forces of Germany, Austria, and the German-speaking cantons of Switzerland. In Nazi Germany, the Kripo was the criminal polic ...

'' (criminal police) from 1923, he and Pöhner participated in Hitler's failed Beer Hall Putsch

The Beer Hall Putsch, also known as the Munich Putsch,Dan Moorhouse, ed schoolshistory.org.uk, accessed 2008-05-31.Known in German as the or was a failed coup d'état by Nazi Party ( or NSDAP) leader Adolf Hitler, Erich Ludendorff and othe ...

on 9 November. Frick tried to suppress the State Police

State police, provincial police or regional police are a type of sub-national territorial police force found in nations organized as federations, typically in North America, South Asia, and Oceania. These forces typically have jurisdiction o ...

's operation, wherefore he was arrested and imprisoned, and tried for aiding and abetting high treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

by the People's Court in April 1924. After several months in custody, he was given a suspended sentence of 15 months' imprisonment and was dismissed from his police job. Later during the disciplinary proceedings, the dismissal was declared unfair and revoked, on the basis that his treasonous intention had not been proven. Frick went on to work at the Munich social insurance

Social insurance is a form of social welfare that provides insurance against economic risks. The insurance may be provided publicly or through the subsidizing of private insurance. In contrast to other forms of social assistance, individuals' ...

office from 1926 onwards, in the rank of a ''Regierungsrat'' 1st class by 1933.

In the aftermath of the putsch, Wilhelm Frick was elected a member of the German '' Reichstag'' parliament in the federal election of May 1924. He had been nominated by the National Socialist Freedom Movement

The National Socialist Freedom Movement (, NSFB) or National Socialist Freedom Party (, NSFP) was a political party in Weimar Germany created in April 1924 during the aftermath of the Beer Hall Putsch. Adolf Hitler and many Nazi leaders were ...

, an electoral list

An electoral list is a grouping of candidates for election, usually found in proportional or mixed electoral systems, but also in some plurality electoral systems. An electoral list can be registered by a political party (a party list) or can ...

of the far-right German Völkisch Freedom Party and then banned Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

. On 1 September 1925, Frick joined the re-established Nazi Party. On 20 May 1928, he was one of the first 12 deputies elected to the ''Reichstag'' as Nazi Party members. He associated himself with the radical Gregor Strasser

Gregor Strasser (also german: Straßer, see ß; 31 May 1892 – 30 June 1934) was an early prominent German Nazi official and politician who was murdered during the Night of the Long Knives in 1934. Born in 1892 in Bavaria, Strasser served i ...

; making his name by aggressive anti-democratic and antisemitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

Reichstag speeches, he climbed to the post of the Nazi parliamentary group leader

A parliamentary leader is a political title or a descriptive term used in various countries to designate the person leading a parliamentary group or caucus in a legislative body, whether it be a national or sub-national legislature. They are their ...

(''Fraktionsführer'') in 1928. He would continue to be elected to the ''Reichstag'' in every subsequent election in the Weimar and Nazi regimes.

In 1929, as the price for joining the coalition government of the ''Land'' (state) of Thuringia

Thuringia (; german: Thüringen ), officially the Free State of Thuringia ( ), is a state of central Germany, covering , the sixth smallest of the sixteen German states. It has a population of about 2.1 million.

Erfurt is the capital and larg ...

, the NSDAP received the state ministries of the Interior and Education. On 23 January 1930, Frick was appointed to these ministries, becoming the first Nazi to hold a ministerial-level post at any level in Germany (though he remained a member of the Reichstag). Frick used his position to dismiss Communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

and Social Democratic officials and replace them with Nazi Party members, so Thuringia's federal subsidies were temporarily suspended by Reich Minister Carl Severing

Carl Wilhelm Severing (1 June 1875, Herford, Westphalia – 23 July 1952, Bielefeld) was a German Social Democrat politician during the Weimar era.

He was seen as a representative of the right wing of the party. Over the years, he took a leadi ...

. Frick also appointed the eugenicist Hans F. K. Günther as a professor of social anthropology

Social anthropology is the study of patterns of behaviour in human societies and cultures. It is the dominant constituent of anthropology throughout the United Kingdom and much of Europe, where it is distinguished from cultural anthropology. In t ...

at the University of Jena

The University of Jena, officially the Friedrich Schiller University Jena (german: Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena, abbreviated FSU, shortened form ''Uni Jena''), is a public research university located in Jena, Thuringia, Germany.

The un ...

, banned several newspapers, and banned pacifist

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaign ...

drama and anti-war films such as '' All Quiet on the Western Front''. He was removed from office by a Social Democratic motion of no confidence

A motion of no confidence, also variously called a vote of no confidence, no-confidence motion, motion of confidence, or vote of confidence, is a statement or vote about whether a person in a position of responsibility like in government or mana ...

in the Thuringian Landtag

A Landtag (State Diet) is generally the legislative assembly or parliament of a federated state or other subnational self-governing entity in German-speaking nations. It is usually a unicameral assembly exercising legislative competence in non- ...

parliament on 1 April 1931.

Reich Minister

When Reich president

When Reich president Paul von Hindenburg

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (; abbreviated ; 2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a German field marshal and statesman who led the Imperial German Army during World War I and later became President of Germany fr ...

appointed Hitler chancellor on 30 January 1933, Frick joined his government as ''Reichsminister

Reichsminister (in German singular and plural; 'minister of the realm') was the title of members of the German Government during two historical periods: during the March revolution of 1848/1849 in the German Reich of that period, and in the mode ...

'' of the Interior. Together with Reichstag President Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring (or Goering; ; 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German politician, military leader and convicted war criminal. He was one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party, which ruled Germany from 1933 to 1 ...

, he was one of only two Nazi ''Reichsministers'' in the original Hitler Cabinet, and the only one who actually had a portfolio; Göring served as minister without portfolio

A minister without portfolio is either a government minister with no specific responsibilities or a minister who does not head a particular ministry. The sinecure is particularly common in countries ruled by coalition governments and a cabinet w ...

until 5 May. Though Frick held a key position, especially in organizing the federal elections of March 1933, he initially had far less power than his counterparts in the rest of Europe. Notably, he had no authority over the police; in Germany law enforcement has traditionally been a state

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* ''Our S ...

and local matter. Indeed, the main reason that Hindenburg and Franz von Papen agreed to give the Interior Ministry to the Nazis was that it was almost powerless at the time. A mighty rival arose in the establishment of the Propaganda Ministry under Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazi politician who was the ''Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief propagandist for the Nazi Party, and then Reich Minister of Propaganda from 1933 to 19 ...

on 13 March.

Frick's power dramatically increased as a result of the Reichstag Fire Decree

The Reichstag Fire Decree (german: Reichstagsbrandverordnung) is the common name of the Decree of the Reich President for the Protection of People and State (german: Verordnung des Reichspräsidenten zum Schutz von Volk und Staat) issued by Germ ...

and the Enabling Act of 1933

The Enabling Act (German: ') of 1933, officially titled ' (), was a law that gave the German Cabinet – most importantly, the Chancellor – the powers to make and enforce laws without the involvement of the Reichstag or Weimar Presi ...

. The provision of the Reichstag Fire Decree giving the cabinet the power to take over state governments on its own authority was actually his idea; he saw the fire as a chance to increase his power and begin the process of Nazifying the country. He was responsible for drafting many of the ''Gleichschaltung

The Nazi term () or "coordination" was the process of Nazification by which Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party successively established a system of totalitarian control and coordination over all aspects of German society and societies occupied b ...

'' laws that consolidated the Nazi regime. Within a few days of the Enabling Act's passage, Frick helped draft a law appointing ''Reichskommissar

(, rendered as "Commissioner of the Empire", "Reich Commissioner" or "Imperial Commissioner"), in German history, was an official gubernatorial title used for various public offices during the period of the German Empire and Nazi Germany.

Germa ...

e'' to disempower the state governments. Under the Law for the Reconstruction of the Reich, which converted Germany into a highly centralized state, the newly implemented '' Reichsstatthalter'' (state governors) were directly responsible to him. Frick also was made a member of Hans Frank

Hans Michael Frank (23 May 1900 – 16 October 1946) was a German politician and lawyer who served as head of the General Government in Nazi-occupied Poland during the Second World War.

Frank was an early member of the German Workers' Party ...

's Academy for German Law

The Academy for German Law (german: Akademie für deutsches Recht) was an institute for legal research and reform founded on 26 June 1933 in Nazi Germany. After suspending its operations during the Second World War in August 1944, it was abolished ...

. On 10 October 1933, Hitler appointed him a '' Reichsleiter'', the second highest political rank in the Nazi Party. In May 1934, he was appointed Prussian

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

Minister of the Interior under Minister-President Göring, which gave him control over the police in Prussia. By 1935, he also had near-total control over local government. He had the sole power to appoint the mayors of all municipalities with populations greater than 100,000 (except for the city state

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world since the dawn of history, including cities such as ...

s of Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

and Hamburg

(male), (female) en, Hamburger(s),

Hamburgian(s)

, timezone1 = Central (CET)

, utc_offset1 = +1

, timezone1_DST = Central (CEST)

, utc_offset1_DST = +2

, postal ...

, where Hitler reserved the right to appoint the mayors himself if he deemed it necessary). He also had considerable influence over smaller towns as well; while their mayors were appointed by the state governors, as mentioned earlier the governors were responsible to him.

Frick was instrumental in the

Frick was instrumental in the racial policy of Nazi Germany

The racial policy of Nazi Germany was a set of policies and laws implemented in Nazi Germany under the dictatorship of Adolf Hitler, based on a specific racist doctrine asserting the superiority of the Aryan race, which claimed scientific legi ...

drafting laws against Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

citizens, like the "Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service

The Law for the Restoration of the Professional Hitler Service (german: Gesetz zur Wiederherstellung des Berufsbeamtentums, shortened to ''Berufsbeamtengesetz''), also known as Civil Service Law, Civil Service Restoration Act, and Law to Re-es ...

" and the notorious Nuremberg Laws

The Nuremberg Laws (german: link=no, Nürnberger Gesetze, ) were antisemitic and racist laws that were enacted in Nazi Germany on 15 September 1935, at a special meeting of the Reichstag convened during the annual Nuremberg Rally of ...

in September 1935. Already in July 1933, he had implemented the Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring including forced sterilizations, which later culminated in the killings of the Action T4

(German, ) was a campaign of mass murder by involuntary euthanasia in Nazi Germany. The term was first used in post-war trials against doctors who had been involved in the killings. The name T4 is an abbreviation of 4, a street address of t ...

"euthanasia" programme supported by his ministry. Frick also took a leading part in Germany's re-armament in violation of the 1919 Versailles Treaty

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

. He drafted laws introducing universal military conscription and extending the Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previous ...

service law to Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

after the 1938 ''Anschluss

The (, or , ), also known as the (, en, Annexation of Austria), was the annexation of the Federal State of Austria into the German Reich on 13 March 1938.

The idea of an (a united Austria and Germany that would form a " Greater Germany ...

'', as well as to the "Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and sk, Sudety) is the historical German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the ...

" territories of the First Czechoslovak Republic

The First Czechoslovak Republic ( cs, První československá republika, sk, Prvá česko-slovenská republika), often colloquially referred to as the First Republic ( cs, První republika, Slovak: ''Prvá republika''), was the first Czechoslo ...

annexed according to the Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Nazi Germany, Germany, the United Kingdom, French Third Republic, France, and Fa ...

.

In the summer of 1938 Frick was named the patron ''(Schirmherr)'' of the Deutsches Turn- und Sportfest in Breslau, a patriotic sports festival attended by Hitler and much of the Nazi leadership. In this event he presided the ceremony of "handing over" the new Nazi Reich Sports League (NSRL) standard to ''Reichssportführer'' Hans von Tschammer und Osten

Hans von Tschammer und Osten (25 October 1887 – 25 March 1943) was a German sport official, SA leader and a member of the Reichstag for the Nazi Party of Nazi Germany. He was married to Sophie Margarethe von Carlowitz.

Hans von Tschammer un ...

, marking the further nazification of sports in Germany. On 11 November 1938, Frick promulgated the Regulations Against Jews' Possession of Weapons.

From the mid-to-late 1930s Frick lost favour irreversibly within the Nazi Party after a power struggle involving attempts to resolve the lack of coordination within the Reich government. For example, in 1933 he tried to restrict the widespread use of "protective custody" orders that were used to send people to concentration camps, only to be begged off by ''Reichsführer-SS

(, ) was a special title and rank that existed between the years of 1925 and 1945 for the commander of the (SS). ''Reichsführer-SS'' was a title from 1925 to 1933, and from 1934 to 1945 it was the highest rank of the SS. The longest-servi ...

'' Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was of the (Protection Squadron; SS), and a leading member of the Nazi Party of Germany. Himmler was one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany and a main architect of th ...

. His power was greatly reduced in June 1936 when Hitler named Himmler the Chief of German Police, which effectively united the police with the SS. On paper, Frick was Himmler's immediate superior. In fact, the police were now independent of Frick's control, since the SS was responsible only to Hitler. A long-running power struggle between the two culminated in Frick's being replaced by Himmler as ''Reichsminister'' of the Interior in August 1943. However, he remained in the cabinet as a ''Reichsminister'' without portfolio. Besides Hitler, he and Lutz Graf Schwerin von Krosigk

Johann Ludwig "Lutz" Graf Schwerin von Krosigk (Born Johann Ludwig von Krosigk; 22 August 18874 March 1977) was a German senior government official who served as the minister of Finance of Germany from 1932 to 1945 and ''de facto'' chancellor ...

were the only members of the Third Reich's cabinet to serve continuously from Hitler's appointment as Chancellor until his death.

Frick's replacement as ''Reichsminister'' of the Interior did not reduce the growing administrative chaos and infighting between party and state agencies. Frick was then appointed as Protector of Bohemia and Moravia, making him Hitler's personal representative in the Czech lands

The Czech lands or the Bohemian lands ( cs, České země ) are the three historical regions of Bohemia, Moravia, and Czech Silesia. Together the three have formed the Czech part of Czechoslovakia since 1918, the Czech Socialist Republic since 1 ...

. Its capital Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

, where Frick used ruthless methods to counter dissent, was one of the last Axis

An axis (plural ''axes'') is an imaginary line around which an object rotates or is symmetrical. Axis may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Axis of rotation: see rotation around a fixed axis

* Axis (mathematics), a designator for a Cartesian-coordinat ...

-held cities to fall at the end of World War II in Europe.

Trial and execution

Frick was arrested, and was arraigned at the

Frick was arrested, and was arraigned at the Nuremberg trials

The Nuremberg trials were held by the Allies of World War II, Allies against representatives of the defeated Nazi Germany, for plotting and carrying out invasions of other countries, and other crimes, in World War II.

Between 1939 and 1945 ...

, where he was the only defendant besides Rudolf Hess

Rudolf Walter Richard Hess (Heß in German; 26 April 1894 – 17 August 1987) was a German politician and a leading member of the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany. Appointed Deputy Führer to Adolf Hitler in 1933, Hess held that position unt ...

who refused to testify on his own behalf. Frick was convicted of planning, initiating and waging wars of aggression, war crimes and crimes against humanity

Crimes against humanity are widespread or systemic acts committed by or on behalf of a ''de facto'' authority, usually a state, that grossly violate human rights. Unlike war crimes, crimes against humanity do not have to take place within the ...

, and for his role, as Minister of the Interior, in formulating the Enabling Act and the Nuremberg Laws

The Nuremberg Laws (german: link=no, Nürnberger Gesetze, ) were antisemitic and racist laws that were enacted in Nazi Germany on 15 September 1935, at a special meeting of the Reichstag convened during the annual Nuremberg Rally of ...

– laws under which people were deported to concentration camps

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

, many of them being murdered there. Frick was also accused of being one of the most senior people responsible for the existence of the concentration camps.

Frick was sentenced to death on 1 October 1946, and was hanged

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a noose or ligature around the neck.Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Hanging as method of execution is unknown, as method of suicide from 1325. The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' states that hanging i ...

at Nuremberg Prison on 16 October. Of his execution, journalist Joseph Kingsbury-Smith wrote:

His body, along with those of the other nine executed men and the corpse of Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring (or Goering; ; 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German politician, military leader and convicted war criminal. He was one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party, which ruled Germany from 1933 to 1 ...

, was cremated at the Ostfriedhof Cemetery in Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the States of Germany, German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the List of cities in Germany by popu ...

, and the ashes were scattered in the river Isar

The Isar is a river in Tyrol, Austria, and Bavaria, Germany, which is not navigable for watercraft above raft size. Its source is in the Karwendel range of the Alps in Tyrol; it enters Germany near Mittenwald and flows through Bad Tölz, Munic ...

.

See also

*Glossary of Nazi Germany

This is a list of words, terms, concepts and slogans of Nazi Germany used in the historiography covering the Nazi regime.

Some words were coined by Adolf Hitler and other Nazi Party members. Other words and concepts were borrowed and appropriated, ...

* List of Nazi Party leaders and officials

This is a list of Nazi Party (NSDAP) leaders and officials. It is not meant to be an all inclusive list.

A

* Gunter d'Alquen – Chief Editor of the SS official newspaper, '' Das Schwarze Korps'' ("The Black Corps"), and commander of the SS ...

References

Sources

* *Further reading

Sautter, ''Wilhelm Frick: Der Legalist des Unrechtsstaates: Eine politische Biographie'', Canadian Journal of History, April 1993

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Frick, Wilhelm 1877 births 1946 deaths Christian fascists Executed people from Rhineland-Palatinate German nationalists German people convicted of crimes against humanity German people convicted of the international crime of aggression German people convicted of war crimes German Protestants German Völkisch Freedom Party politicians Heidelberg University alumni Interior ministers of Prussia Holocaust perpetrators in Germany Jurists from Rhineland-Palatinate Lawyers in the Nazi Party Members of the Academy for German Law Members of the Reichstag of Nazi Germany Members of the Reichstag of the Weimar Republic National Socialist Freedom Movement politicians Nazi Germany ministers Nazi Party officials Nazi Party politicians Nazis who participated in the Beer Hall Putsch People executed by the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg People executed for crimes against humanity People from Donnersbergkreis People from the Kingdom of Bavaria People from the Palatinate (region) Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia Reichsleiters Thule Society members