Westminster Abbey on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly

/ref> Sixteen royal weddings have occurred at the abbey since 1100. According to a tradition first reported by

Between 1042 and 1052, Edward the Confessor began rebuilding St Peter's Abbey to provide himself with a royal burial church. It was the first church in England built in the Romanesque style. The building was completed around 1060 and was consecrated on 28 December 1065, only a week before Edward's death on 5 January 1066. A week later, he was buried in the church; nine years later, his wife

Between 1042 and 1052, Edward the Confessor began rebuilding St Peter's Abbey to provide himself with a royal burial church. It was the first church in England built in the Romanesque style. The building was completed around 1060 and was consecrated on 28 December 1065, only a week before Edward's death on 5 January 1066. A week later, he was buried in the church; nine years later, his wife

Released from the burdens of spiritual leadership, which passed to the reformed Cluniac movement after the mid-10th century, and occupied with the administration of great landed properties, some of which lay far from Westminster, "the Benedictines achieved a remarkable degree of identification with the secular life of their times, and particularly with upper-class life", Barbara Harvey concludes, to the extent that her depiction of daily life provides a wider view of the concerns of the English gentry in the

Released from the burdens of spiritual leadership, which passed to the reformed Cluniac movement after the mid-10th century, and occupied with the administration of great landed properties, some of which lay far from Westminster, "the Benedictines achieved a remarkable degree of identification with the secular life of their times, and particularly with upper-class life", Barbara Harvey concludes, to the extent that her depiction of daily life provides a wider view of the concerns of the English gentry in the

. Retrieved 29 April 2011 The first building stage included the entire eastern end, the

The abbey was restored to the Benedictines under the Catholic

The abbey was restored to the Benedictines under the Catholic

The Joint Committee responsible for assembling the

The Joint Committee responsible for assembling the

Royal weddings have included:

Royal weddings have included:

On 6 September 1997 the formal, though not state

On 6 September 1997 the formal, though not state

Westminster Abbey is renowned for its choral tradition, and the repertoire of

Westminster Abbey is renowned for its choral tradition, and the repertoire of

,

The chapter house was built concurrently with the east parts of the abbey under Henry III, between about 1245 and 1253. It was

The chapter house was built concurrently with the east parts of the abbey under Henry III, between about 1245 and 1253. It was

Walter Thornbury, Old and New London, Volume 3, 1878, pp. 394вҖ“462, British History Online

Westminster Abbey Article at EncyclopГҰdia Britannica

Historic images of Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey: A Peek Inside

вҖ“ slideshow by ''Life magazine, Life'' magazine

Keith Short вҖ“ Sculptor

Images of stone carving for Westminster Abbey

* [http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/15598a.htm/ Catholic Encyclopedia: Westminster Abbey]

Adrian FletcherвҖҷs Paradoxplace Westminster Abbey PagesвҖ”Photos

* A panorama of Westminster Abbey in daytime вҖ

version

Westminster Abbey on Twitter

Audio Guide of Westminster Abbey

{{Authority control Westminster Abbey, Churches completed in 1745 Christian monasteries established in the 10th century Church of England church buildings in the City of Westminster, Abbey Collegiate churches in England Coronation church buildings English Gothic architecture in Greater London Gothic architecture in England Grade I listed churches in the City of Westminster Nicholas Hawksmoor buildings Monasteries in London Religion in the City of Westminster, Abbey Royal Peculiars, London, Westminster Abbey, Abbey Tourist attractions in the City of Westminster, Abbey World Heritage Sites in London 13th-century architecture in the United Kingdom Edward Blore buildings Burial sites of the House of Tudor Burial sites of the House of Stuart Former cathedrals in London 1st-millennium establishments in England Burial sites of the House of Hanover Monasteries dissolved under the English Reformation

Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

church

Church may refer to:

Religion

* Church (building), a building for Christian religious activities

* Church (congregation), a local congregation of a Christian denomination

* Church service, a formalized period of Christian communal worship

* C ...

in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United Kingdom's most notable religious buildings and since Edward the Confessor, a burial site for English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

and, later, British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

monarchs. Since the coronation

A coronation is the act of placement or bestowal of a crown upon a monarch's head. The term also generally refers not only to the physical crowning but to the whole ceremony wherein the act of crowning occurs, along with the presentation of ot ...

of William the Conqueror

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33вҖ“ 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first House of Normandy, Norman List of English monarchs#House of Norman ...

in 1066, all coronations of English and British monarchs have occurred in Westminster Abbey.Westminster-abbey.org/ref> Sixteen royal weddings have occurred at the abbey since 1100. According to a tradition first reported by

Sulcard

Sulcard (floruit ''c''. 1080) was a Benedictine monk at St. Peter's, Westminster Abbey, and the author of the first history of the abbey.

Little is known of Sulcard, whose unusual name may reflect either Anglo-Saxon or Norman parentage.Harvey, "Su ...

in about 1080, a church was founded at the site (then known as Thorney Island) in the seventh century, at the time of Mellitus

Saint Mellitus (died 24 April 624) was the first bishop of London in the Saxon period, the third Archbishop of Canterbury, and a member of the Gregorian mission sent to England to convert the Anglo-Saxons from their native paganism to Chris ...

, Bishop of London

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

. Construction of the present church began in 1245 on the orders of Henry III.

The church was originally part of a Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

Benedictine

, image = Medalla San Benito.PNG

, caption = Design on the obverse side of the Saint Benedict Medal

, abbreviation = OSB

, formation =

, motto = (English: 'Pray and Work')

, foun ...

abbey

An abbey is a type of monastery used by members of a religious order under the governance of an abbot or abbess. Abbeys provide a complex of buildings and land for religious activities, work, and housing of Christian monks and nuns.

The con ...

, which was dissolved in 1539. It then served as the cathedral of the Diocese of Westminster Diocese of Westminster may refer to:

* Roman Catholic Diocese of Westminster, since 1850, with seat at Westminster Cathedral

* Diocese of Westminster (Church of England)

The Diocese of Westminster was a short-lived diocese of the Church of Engl ...

until 1550, then as a second cathedral of the Diocese of London until 1556. The abbey was restored to the Benedictines by Mary I

Mary I (18 February 1516 вҖ“ 17 November 1558), also known as Mary Tudor, and as "Bloody Mary" by her Protestant opponents, was Queen of England and Ireland from July 1553 and Queen of Spain from January 1556 until her death in 1558. She ...

in 1556, then in 1559 made a royal peculiar

A royal peculiar is a Church of England parish or church exempt from the jurisdiction of the diocese and the province in which it lies, and subject to the direct jurisdiction of the monarch, or in Cornwall by the duke.

Definition

The church par ...

вҖ”a Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

church responsible directly to the sovereignвҖ”by Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is ...

.

The abbey is the burial site of more than 3,300 people, usually of prominence in British history: at least 16 monarchs, eight prime ministers

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is no ...

, poets laureate, actors, scientists, military leaders, and the Unknown Warrior

The British grave of the Unknown Warrior (often known as 'The Tomb of the Unknown Warrior') holds an unidentified member of the British armed forces killed on a European battlefield during the First World War.Hanson, Chapters 23 & 24 He was gi ...

.

History

A late tradition claims that Aldrich, a young fisherman on theRiver Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after the R ...

, had a vision

Vision, Visions, or The Vision may refer to:

Perception Optical perception

* Visual perception, the sense of sight

* Visual system, the physical mechanism of eyesight

* Computer vision, a field dealing with how computers can be made to gain und ...

of Saint Peter

) (Simeon, Simon)

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Bethsaida, Gaulanitis, Syria, Roman Empire

, death_date = Between AD 64вҖ“68

, death_place = probably Vatican Hill, Rome, Italia, Roman Empire

, parents = John (or Jonah; Jona)

, occupat ...

near the site. This seems to have been quoted as the origin of the salmon that Thames fishermen offered to the abbey in later years, a custom still observed annually by the Fishmongers' Company

The Worshipful Company of Fishmongers (or Fishmongers' Company) is one of the 110 Livery Companies of the City of London, being an incorporated guild of sellers of fish and seafood in the City. The Company ranks fourth in the order of precede ...

. The recorded origins of the abbey date to the 960s or early 970s, when Saint Dunstan

Saint Dunstan (c. 909 вҖ“ 19 May 988) was an English bishop. He was successively Abbot of Glastonbury Abbey, Bishop of Worcester, Bishop of London and Archbishop of Canterbury, later canonised as a saint. His work restored monastic life in E ...

and King Edgar installed a community of Benedictine

, image = Medalla San Benito.PNG

, caption = Design on the obverse side of the Saint Benedict Medal

, abbreviation = OSB

, formation =

, motto = (English: 'Pray and Work')

, foun ...

monk

A monk (, from el, ОјОҝОҪОұПҮПҢПӮ, ''monachos'', "single, solitary" via Latin ) is a person who practices religious asceticism by monastic living, either alone or with any number of other monks. A monk may be a person who decides to dedica ...

s on the site.

1042: Edward the Confessor starts rebuilding St Peter's Abbey

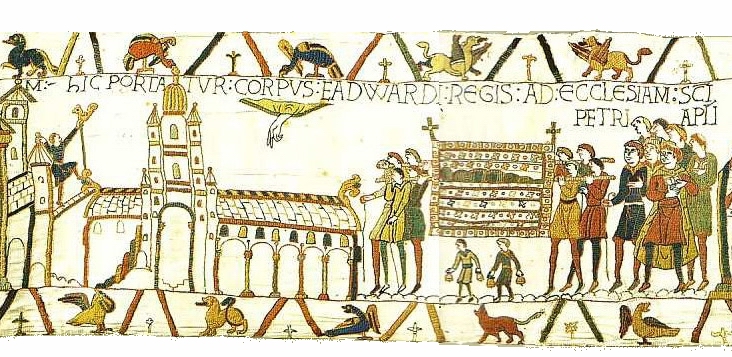

Between 1042 and 1052, Edward the Confessor began rebuilding St Peter's Abbey to provide himself with a royal burial church. It was the first church in England built in the Romanesque style. The building was completed around 1060 and was consecrated on 28 December 1065, only a week before Edward's death on 5 January 1066. A week later, he was buried in the church; nine years later, his wife

Between 1042 and 1052, Edward the Confessor began rebuilding St Peter's Abbey to provide himself with a royal burial church. It was the first church in England built in the Romanesque style. The building was completed around 1060 and was consecrated on 28 December 1065, only a week before Edward's death on 5 January 1066. A week later, he was buried in the church; nine years later, his wife Edith

Edith is a feminine given name derived from the Old English words Д“ad, meaning 'riches or blessed', and is in common usage in this form in English, German, many Scandinavian languages and Dutch. Its French form is Гүdith. Contractions and var ...

was buried alongside him. His successor, Harold Godwinson

Harold Godwinson ( вҖ“ 14 October 1066), also called Harold II, was the last crowned Anglo-Saxon English king. Harold reigned from 6 January 1066 until his death at the Battle of Hastings, fighting the Norman invaders led by William the ...

, was probably crowned here, although the first documented coronation is that of William the Conqueror

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33вҖ“ 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first House of Normandy, Norman List of English monarchs#House of Norman ...

later the same year.

The only extant depiction of Edward's abbey, together with the adjacent Palace of Westminster, is in the Bayeux Tapestry. Some of the lower parts of the monastic dormitory, an extension of the South Transept, survive in the Norman Undercroft of the Great School, including a door said to come from the previous Saxon abbey. Increased endowments supported a community that increased from a dozen monks during Dunstan's time, up to as many as eighty monks.

Construction of the present church

Released from the burdens of spiritual leadership, which passed to the reformed Cluniac movement after the mid-10th century, and occupied with the administration of great landed properties, some of which lay far from Westminster, "the Benedictines achieved a remarkable degree of identification with the secular life of their times, and particularly with upper-class life", Barbara Harvey concludes, to the extent that her depiction of daily life provides a wider view of the concerns of the English gentry in the

Released from the burdens of spiritual leadership, which passed to the reformed Cluniac movement after the mid-10th century, and occupied with the administration of great landed properties, some of which lay far from Westminster, "the Benedictines achieved a remarkable degree of identification with the secular life of their times, and particularly with upper-class life", Barbara Harvey concludes, to the extent that her depiction of daily life provides a wider view of the concerns of the English gentry in the High

High may refer to:

Science and technology

* Height

* High (atmospheric), a high-pressure area

* High (computability), a quality of a Turing degree, in computability theory

* High (tectonics), in geology an area where relative tectonic uplift ...

and Late Middle Ages

The Late Middle Ages or Late Medieval Period was the period of European history lasting from AD 1300 to 1500. The Late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period (and in much of Europe, the Renai ...

.

The abbot

Abbot is an ecclesiastical title given to the male head of a monastery in various Western religious traditions, including Christianity. The office may also be given as an honorary title to a clergyman who is not the head of a monastery. The fem ...

and monks, being adjacent to the Palace of Westminster (the seat of government from the late 13th century), became a powerful force in the centuries after the Norman Conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Norman, Breton, Flemish, and French troops, all led by the Duke of Normandy, later styled William the Conque ...

, with the Abbot of Westminster

The Abbot of Westminster was the head (abbot) of Westminster Abbey.

List

Notes

ReferencesTudorplace.com.ar

{Unreliable source?, certain=y, reason=self published website; and Jorge H. Castelli is not an expert, date=January 2015 Abbots of W ...

taking his place in the {Unreliable source?, certain=y, reason=self published website; and Jorge H. Castelli is not an expert, date=January 2015 Abbots of W ...

House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the Bicameralism, upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by Life peer, appointment, Hereditary peer, heredity or Lords Spiritual, official function. Like the ...

in due course. The proximity to the palace did not however extend to providing them with high royal connections; in social origin, the Benedictines of Westminster were as modest as most of the order. The abbot remained Lord of the manor

Lord of the Manor is a title that, in Anglo-Saxon England, referred to the landholder of a rural estate. The lord enjoyed manorial rights (the rights to establish and occupy a residence, known as the manor house and demesne) as well as seig ...

of Westminster as a town of two to three thousand people grew around it: as a consumer and employer on a grand scale, the monastery helped fuel the town's economy, and relations with the town remained unusually cordial, but no enfranchising charter was issued during the Middle Ages.

Westminster Abbey became the coronation site of Norman kings, but none were buried there until Henry III rebuilt it in the Anglo-French Gothic style as a shrine to venerate King Edward the Confessor and as a suitably regal setting for his own tomb, under the highest Gothic nave

The nave () is the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts, or in a church without transepts, to the chancel. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-type ...

in England. The Confessor's shrine subsequently played a great part in his canonization

Canonization is the declaration of a deceased person as an officially recognized saint, specifically, the official act of a Christian communion declaring a person worthy of public veneration and entering their name in the canon catalogue of ...

.

Construction began in 1245.History вҖ“ Westminster Abbey. Retrieved 29 April 2011 The first building stage included the entire eastern end, the

transept

A transept (with two semitransepts) is a transverse part of any building, which lies across the main body of the building. In cruciform churches, a transept is an area set crosswise to the nave in a cruciform ("cross-shaped") building wi ...

s, and the easternmost bay of the nave

The nave () is the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts, or in a church without transepts, to the chancel. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-type ...

. The Lady chapel

A Lady chapel or lady chapel is a traditional British English, British term for a chapel dedicated to "Our Lady", Mary, mother of Jesus, particularly those inside a cathedral or other large church (building), church. The chapels are also known as ...

, built from around 1220 at the extreme eastern end, was incorporated into the chevet of the new building, but was later replaced. This work must have been largely completed by 1258вҖ“60, when the second stage began. This carried the nave on an additional five bays, bringing it to one bay beyond the ritual choir

A choir ( ; also known as a chorale or chorus) is a musical ensemble of singers. Choral music, in turn, is the music written specifically for such an ensemble to perform. Choirs may perform music from the classical music repertoire, which ...

. Here, construction stopped in about 1269. A consecration ceremony being held on 13 October of that year, but because of Henry's death, construction did not resume. The old Romanesque nave remained attached to the new building for over a century, until it was pulled down and rebuilt from 1376, closely following the original (and by now outdated) design. Construction was largely finished by the architect Henry Yevele

Henry Yevele (''c''. 1320 вҖ“ 1400) was the most prolific and successful master mason active in late medieval England. The first document relating to him is dated 3 December 1353, when he purchased the freedom of London. In February 1356 he was su ...

in the reign of Richard II.

Henry III also commissioned the unique Cosmati

The Cosmati were a Roman family, seven members of which, for four generations, were skilful architects, sculptors and workers in decorative geometric mosaic, mostly for church floors. Their name is commemorated in the genre of Cosmatesque work ...

pavement in front of the High Altar; the pavement was re-dedicated by the Dean at a service on 21 May 2010 after undergoing a major cleaning and conservation programme.

Henry VII added a Perpendicular style

Perpendicular Gothic (also Perpendicular, Rectilinear, or Third Pointed) architecture was the third and final style of English Gothic architecture developed in the Kingdom of England during the Late Middle Ages, typified by large windows, four-ce ...

chapel dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary

Mary; arc, ЬЎЬӘЬқЬЎ, translit=Mariam; ar, Щ…ШұЩҠЩ…, translit=Maryam; grc, ОңОұПҒОҜОұ, translit=MarГӯa; la, Maria; cop, вІҳвІҒвІЈвІ“вІҒ, translit=Maria was a first-century Jews, Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Saint Joseph, Jose ...

in 1503 (known as the "Henry VII Chapel

The Henry VII Lady Chapel, now more often known just as the Henry VII Chapel, is a large Lady chapel at the far eastern end of Westminster Abbey, paid for by the will of King Henry VII. It is separated from the rest of the abbey by brass gates ...

" or the "Lady Chapel"). Much of the stone came from Caen, in France (Caen stone

Caen stone (french: Pierre de Caen) is a light creamy-yellow Jurassic limestone quarried in north-western France near the city of Caen. The limestone is a fine grained oolitic limestone formed in shallow water lagoons in the Bathonian Age about ...

), the Isle of Portland

An isle is an island, land surrounded by water. The term is very common in British English. However, there is no clear agreement on what makes an island an isle or its difference, so they are considered synonyms.

Isle may refer to:

Geography

* Is ...

( Portland stone) and the Loire Valley region of France ( tuffeau limestone). The chapel was finished circa 1519.

16th and 17th centuries: dissolution and restoration

In 1535 during the assessment attendant on the Dissolution of the monasteries, the abbey's annual income was ВЈ3,000 (equivalent to ВЈ in ).1540вҖ“1550: 10 years as a cathedral

Henry VIII assumed direct control in 1539 and granted the abbey the status of a cathedral by charter in 1540, simultaneously issuing letters patent establishing theDiocese of Westminster Diocese of Westminster may refer to:

* Roman Catholic Diocese of Westminster, since 1850, with seat at Westminster Cathedral

* Diocese of Westminster (Church of England)

The Diocese of Westminster was a short-lived diocese of the Church of Engl ...

. By granting the abbey cathedral status, Henry VIII gained an excuse to spare it from the destruction or dissolution which he inflicted on most English abbeys during this period. The abbot, William Benson, became dean

Dean may refer to:

People

* Dean (given name)

* Dean (surname), a surname of Anglo-Saxon English origin

* Dean (South Korean singer), a stage name for singer Kwon Hyuk

* Dean Delannoit, a Belgian singer most known by the mononym Dean

Titles

* ...

of the cathedral, while the prior and five of the monks were among the twelve canons.

After 1550: turbulent times

The Westminster diocese was dissolved in 1550, but the abbey was recognised (in 1552, retroactively to 1550) as a second cathedral of the Diocese of London until 1556. The already-old expression "robbing Peter to pay Paul

"To rob Peter to pay Paul", or other versions that have developed over the centuries such as "to borrow from Peter to pay Paul", and "to unclothe Peter to clothe Paul", are phrases meaning to take from one person or thing to give to another, espec ...

" may have been given a new lease of life when money meant for the abbey, which is dedicated to Saint Peter

) (Simeon, Simon)

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Bethsaida, Gaulanitis, Syria, Roman Empire

, death_date = Between AD 64вҖ“68

, death_place = probably Vatican Hill, Rome, Italia, Roman Empire

, parents = John (or Jonah; Jona)

, occupat ...

, was diverted to the treasury of St Paul's Cathedral.

The abbey was restored to the Benedictines under the Catholic

The abbey was restored to the Benedictines under the Catholic Mary I

Mary I (18 February 1516 вҖ“ 17 November 1558), also known as Mary Tudor, and as "Bloody Mary" by her Protestant opponents, was Queen of England and Ireland from July 1553 and Queen of Spain from January 1556 until her death in 1558. She ...

, but they were again ejected under Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is ...

in 1559. In 1560, Elizabeth re-established Westminster as a "royal peculiar

A royal peculiar is a Church of England parish or church exempt from the jurisdiction of the diocese and the province in which it lies, and subject to the direct jurisdiction of the monarch, or in Cornwall by the duke.

Definition

The church par ...

" вҖ“ a church of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

responsible directly to the sovereign, rather than to a diocesan bishop вҖ“ and made it the Collegiate Church of St Peter (that is, a non-cathedral church with an attached chapter of canons, headed by a dean).

In the early 17th century, the abbey hosted two of the six companies of churchmen, led by Lancelot Andrewes

Lancelot Andrewes (155525 September 1626) was an English bishop and scholar, who held high positions in the Church of England during the reigns of Elizabeth I and James I. During the latter's reign, Andrewes served successively as Bishop of Chi ...

, Dean of Westminster

The Dean of Westminster is the head of the chapter at Westminster Abbey. Due to the Abbey's status as a Royal Peculiar, the dean answers directly to the British monarch (not to the Bishop of London as ordinary, nor to the Archbishop of Canterbu ...

, who translated the King James Version

The King James Version (KJV), also the King James Bible (KJB) and the Authorized Version, is an Bible translations into English, English translation of the Christian Bible for the Church of England, which was commissioned in 1604 and publis ...

of the Bible.

It suffered damage during the turbulent 1640s, when it was attacked by Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Catholic Church, Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become m ...

iconoclasts, but was again protected by its close ties to the state during the Commonwealth period. Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

was given an elaborate funeral there in 1658, only to be disinterred in January 1661 and posthumously hanged from a gibbet

A gibbet is any instrument of public execution (including guillotine, decapitation, executioner's block, Impalement, impalement stake, gallows, hanging gallows, or related Scaffold (execution site), scaffold). Gibbeting is the use of a gallows- ...

at Tyburn

Tyburn was a manor (estate) in the county of Middlesex, one of two which were served by the parish of Marylebone.

The parish, probably therefore also the manor, was bounded by Roman roads to the west (modern Edgware Road) and south (modern O ...

.

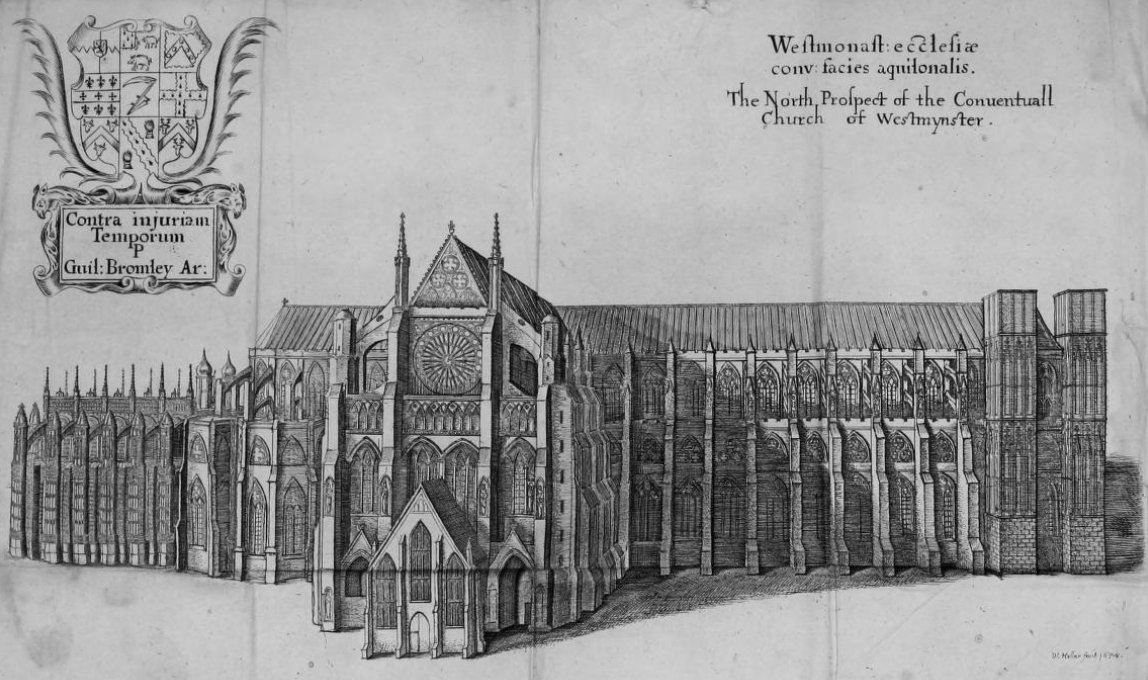

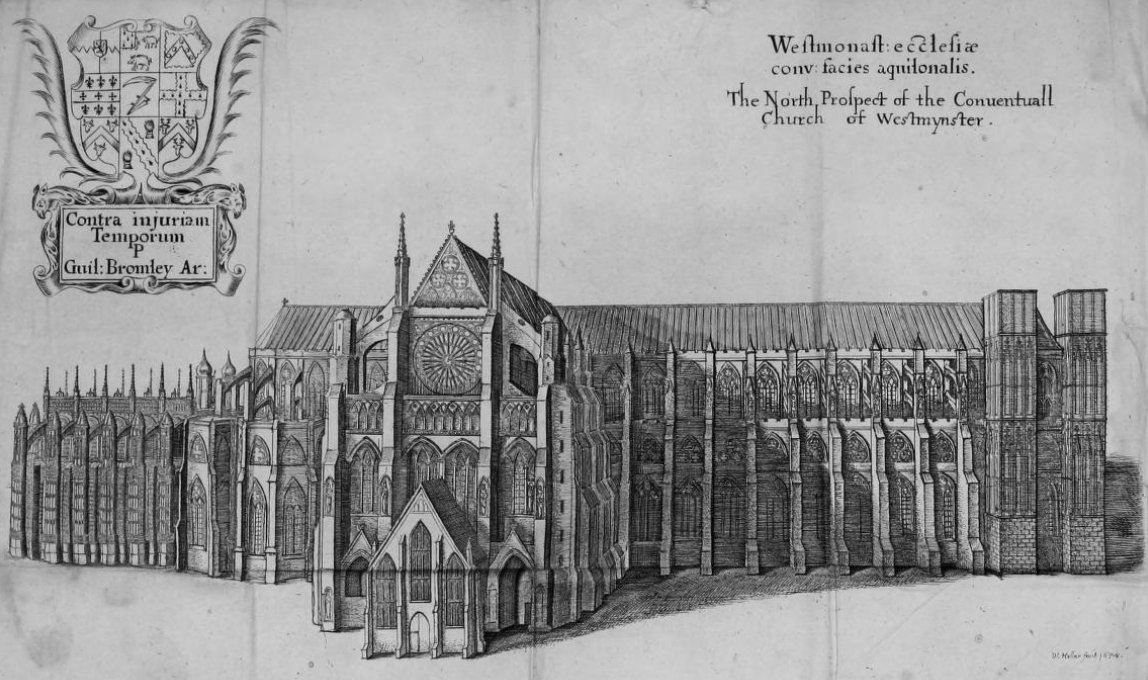

1722вҖ“1745: Western towers constructed

The abbey's two western towers were built between 1722 and 1745 byNicholas Hawksmoor

Nicholas Hawksmoor (probably 1661 вҖ“ 25 March 1736) was an English architect. He was a leading figure of the English Baroque style of architecture in the late-seventeenth and early-eighteenth centuries. Hawksmoor worked alongside the principa ...

, constructed from Portland stone to an early example of a Gothic Revival

Gothic Revival (also referred to as Victorian Gothic, neo-Gothic, or Gothick) is an architectural movement that began in the late 1740s in England. The movement gained momentum and expanded in the first half of the 19th century, as increasingly ...

design. Purbeck marble was used for the walls and the floors, although the various tombstones are made of different types of marble. Images of the abbey prior to the construction of the towers are scarce, though the abbey's official website states that the building had "towers which had been left unfinished in the medieval period".

After an earthquake in 1750, the top of one of the piers on the north side fell down, with the iron and lead that had fastened it. Several houses fell in, and many chimneys were damaged. Another shock had been felt during the preceding month.

On 11 November 1760, the funeral of George II George II or 2 may refer to:

People

* George II of Antioch (seventh century AD)

* George II of Armenia (late ninth century)

* George II of Abkhazia (916вҖ“960)

* Patriarch George II of Alexandria (1021вҖ“1051)

* George II of Georgia (1072вҖ“1089) ...

was held at the abbey and the king was interred next to his late wife, Caroline of Ansbach. He left instructions for the sides of his and his wife's coffins to be removed so that their remains could mingle.

Further rebuilding and restoration occurred in the 19th century under Sir George Gilbert Scott. A narthex

The narthex is an architectural element typical of early Christian and Byzantine basilicas and churches consisting of the entrance or lobby area, located at the west end of the nave, opposite the church's main altar. Traditionally the narthex ...

(a portico or entrance hall) for the west front was designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens in the mid-20th century but was not built.

1914 suffragette bombing

On 11 June 1914, a bomb planted by suffragettes of theWomen's Social and Political Union

The Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) was a women-only political movement and leading militant organisation campaigning for women's suffrage in the United Kingdom from 1903 to 1918. Known from 1906 as the suffragettes, its membership an ...

exploded inside the abbey. The abbey was busy with visitors, with around 80вҖ“100 people in the building at the time of the explosion. Some were as close as from the bomb and the explosion caused a panic for the exits, but no serious injuries were reported. The bomb had been packed with nuts and bolts to act as shrapnel.

The event was part of a campaign of bombing and arson attacks carried out by suffragettes nationwide between 1912 and 1914. Churches were a particular target, as it was believed that the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

was complicit in reinforcing opposition to women's suffrage вҖ“ 32 churches were attacked nationwide between 1913 and 1914.

Coincidentally, at the time of the explosion, the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

only away was debating how to deal with the violent tactics of the suffragettes. Many in the Commons heard the explosion and rushed to the scene. Two days after the Westminster Abbey bombing, a second suffragette bomb was discovered before it could explode in St Paul's Cathedral.

The bomb blew off a corner of the Coronation Chair

The Coronation Chair, known historically as St Edward's Chair or King Edward's Chair, is an ancient wooden chair on which British monarchs sit when they are invested with regalia and crowned at their coronations. It was commissioned in 1296 by ...

. It also caused the Stone of Scone

The Stone of Scone (; gd, An Lia FГ il; sco, Stane o Scuin)вҖ”also known as the Stone of Destiny, and often referred to in England as The Coronation StoneвҖ”is an oblong block of red sandstone that has been used for centuries in the coronati ...

to break in half, although this was not discovered until 1950, when four Scottish nationalists broke into the church to steal the stone and return it to Scotland.

Second World War

Westminster suffered minor damage duringthe Blitz

The Blitz was a German bombing campaign against the United Kingdom in 1940 and 1941, during the Second World War. The term was first used by the British press and originated from the term , the German word meaning 'lightning war'.

The Germa ...

on 15 November 1940. Then on 10/11 May 1941, the Westminster Abbey precincts and roof were hit by incendiary bombs. All the bombs were extinguished by ARP wardens, except for one bomb which ignited out of reach among the wooden beams and plaster vault of the lantern roof (of 1802) over the North Transept. Flames rapidly spread and burning beams and molten lead began to fall on the wooden stalls, pews and other ecclesiastical fixtures below. Despite the falling debris, the staff dragged away as much furniture as possible before withdrawing. Finally the Lantern roof crashed down into the crossing, preventing the fires from spreading further.

Post-war

The Joint Committee responsible for assembling the

The Joint Committee responsible for assembling the New English Bible

The New English Bible (NEB) is an English translation of the Bible. The New Testament was published in 1961 and the Old Testament (with the Apocrypha) was published on 16 March 1970. In 1989, it was significantly revised and republished as the R ...

met twice a year at Westminster Abbey in the 1950s and 1960s.

In the 1990s, two icons by the Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

icon painter Sergei Fyodorov were added. In 1997, the abbey, which was then receiving approximately 1.75 million visitors each year, began charging admission fees to visitors.

On 6 September 1997, the funeral of Diana, Princess of Wales

The funeral of Diana, Princess of Wales, started on Saturday 6 September 1997 at 9:08am in London, when the tenor bell of Westminster Abbey started tolling to signal the departure of the cortГЁge from Kensington Palace. The coffin was carried ...

, was held at the abbey.

In June 2009 the first major building work in 250 years was proposed. A corona

Corona (from the Latin for 'crown') most commonly refers to:

* Stellar corona, the outer atmosphere of the Sun or another star

* Corona (beer), a Mexican beer

* Corona, informal term for the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, which causes the COVID-19 di ...

вҖ“ a crown-like architectural feature вҖ“ was suggested to be built around the lantern over the central crossing, replacing an existing pyramidal structure dating from the 1950s. This was part of a wider ВЈ23m development of the abbey completed in 2013.

On 4 August 2010, the Dean and Chapter announced that, " ter a considerable amount of preliminary and exploratory work", efforts toward the construction of a corona would not be continued. In 2012, architects Panter Hudspith completed refurbishment of the 14th-century food-store originally used by the abbey's monks, converting it into a restaurant with English oak furniture by Covent Garden-based furniture makers Luke Hughes and Company. This is now the Cellarium CafГ© and Terrace.

On 17 September 2010, Pope Benedict XVI

Pope Benedict XVI ( la, Benedictus XVI; it, Benedetto XVI; german: link=no, Benedikt XVI.; born Joseph Aloisius Ratzinger, , on 16 April 1927) is a retired prelate of the Catholic church who served as the head of the Church and the soverei ...

became the first pope to set foot in the abbey, and on 29 April 2011, the wedding of Prince William and Catherine Middleton

The wedding of Prince William and Catherine Middleton took place on Friday, 29 April 2011 at Westminster Abbey in London, England. The groom was second in the line of succession to the British throne. The couple had been in a relationship si ...

took place at the abbey.

The Queen's Diamond Jubilee Galleries were created in the medieval triforium

A triforium is an interior gallery, opening onto the tall central space of a building at an upper level. In a church, it opens onto the nave from above the side aisles; it may occur at the level of the clerestory windows, or it may be locat ...

. This is a display area for the abbey's treasures in the galleries high up around the nave. A new Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

access tower with lift was designed by the abbey architect and Surveyor of the Fabric, Ptolemy Dean

Ptolemy Hugo Dean (born 1968) is a British architect, television presenter and the 19th Surveyor of the Fabric of Westminster Abbey. He specialises in historic preservation, as well as designing new buildings that are in keeping with their hist ...

. The new galleries opened in June 2018.

On 10 March 2021, a vaccination centre opened in Poets' Corner

Poets' Corner is the name traditionally given to a section of the South Transept of Westminster Abbey in the City of Westminster, London because of the high number of poets, playwrights, and writers buried and commemorated there.

The first poe ...

to administer doses of COVID-19 vaccine

A COVID19 vaccine is a vaccine intended to provide acquired immunity against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARSвҖ‘CoVвҖ‘2), the virus that causes coronavirus disease 2019 ( COVID19).

Prior to the COVID19 pandemic, an e ...

s.

On 19 September 2022, the state funeral of Elizabeth II took place at the abbey.

Royal occasions

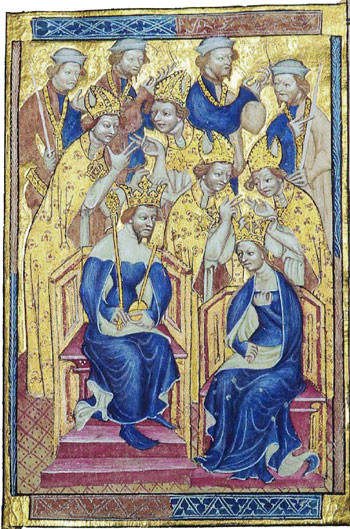

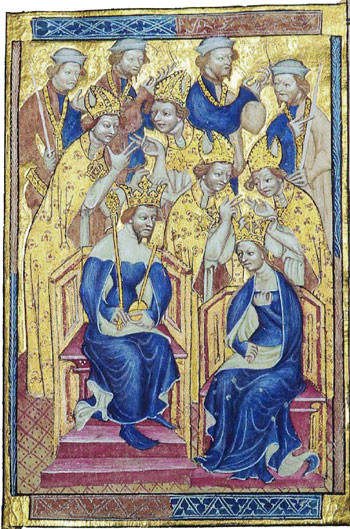

Coronations

Since the coronation in 1066 ofWilliam the Conqueror

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33вҖ“ 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first House of Normandy, Norman List of English monarchs#House of Norman ...

, every English and British monarch (except Edward V and Edward VIII, who were never crowned) has been crowned in Westminster Abbey. In 1216, Henry III could not be crowned in London when he came to the throne, because the French prince Louis Louis may refer to:

* Louis (coin)

* Louis (given name), origin and several individuals with this name

* Louis (surname)

* Louis (singer), Serbian singer

* HMS ''Louis'', two ships of the Royal Navy

See also

Derived or associated terms

* Lewis ( ...

had taken control of the city, and so the king was crowned in the Church of St Peter in Gloucester (which is now Gloucester Cathedral). This coronation was deemed by Pope Honorius III

Pope Honorius III (c. 1150 вҖ“ 18 March 1227), born Cencio Savelli, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 18 July 1216 to his death. A canon at the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore, he came to hold a number of impor ...

to be improper, and a further coronation was held in Westminster Abbey on 17 May 1220.

King Edward's Chair

The Coronation Chair, known historically as St Edward's Chair or King Edward's Chair, is an ancient wooden chair on which British monarchs sit when they are invested with regalia and crowned at their coronations. It was commissioned in 1296 by ...

(or St Edward's Chair), the throne on which English and British sovereigns have been seated at the moment of crowning, is now housed within the abbey in St George's Chapel near the West Door, and has been used at every coronation since 1308. From 1301 to 1996 (except for a short time in 1950 when the stone was temporarily stolen by Scottish nationalists

Scottish independence ( gd, Neo-eisimeileachd na h-Alba; sco, Scots unthirldom) is the idea of Scotland as a sovereign state, independent from the United Kingdom, and refers to the political movement that is campaigning to bring it about.

S ...

), the chair also housed the Stone of Scone

The Stone of Scone (; gd, An Lia FГ il; sco, Stane o Scuin)вҖ”also known as the Stone of Destiny, and often referred to in England as The Coronation StoneвҖ”is an oblong block of red sandstone that has been used for centuries in the coronati ...

upon which the kings of Scots were crowned. Although it is now kept in Scotland, at Edinburgh Castle, it is intended that the stone will be returned temporarily to St Edward's Chair for use during future coronation ceremonies.

Royal weddings

Royal weddings have included:

Royal weddings have included:

Dean and Chapter

Westminster Abbey is acollegiate church In Christianity, a collegiate church is a church where the daily office of worship is maintained by a college of canons: a non-monastic or "secular" community of clergy, organised as a self-governing corporate body, which may be presided over by ...

governed by the Dean and Chapter of Westminster

The Dean and Chapter of Westminster are the ecclesiastical governing body of Westminster Abbey, a collegiate church of the Church of England and royal peculiar in Westminster, Greater London. They consist of the dean and several canons meeting in ...

, as established by Royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, bu ...

of Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is ...

dated 21 May 1560, which created it as the Collegiate Church of St Peter Westminster, a royal peculiar

A royal peculiar is a Church of England parish or church exempt from the jurisdiction of the diocese and the province in which it lies, and subject to the direct jurisdiction of the monarch, or in Cornwall by the duke.

Definition

The church par ...

under the personal jurisdiction of the sovereign. The members of the Chapter are the Dean and four canons residentiary; they are assisted by the Receiver General and Chapter Clerk. One of the canons is also Rector of St Margaret's Church, Westminster, and often also holds the post of Chaplain to the Speaker of the House of Commons Speaker of the House of Commons is a political leadership position found in countries that have a House of Commons, where the membership of the body elects a speaker to lead its proceedings.

Systems that have such a position include:

* Speaker of ...

. In addition to the dean and canons, there are at present three full-time minor canons: the precentor

A precentor is a person who helps facilitate worship. The details vary depending on the religion, denomination, and era in question. The Latin derivation is ''prГҰcentor'', from cantor, meaning "the one who sings before" (or alternatively, "first ...

, the sacrist

A sacristan is an officer charged with care of the sacristy, the church, and their contents.

In ancient times, many duties of the sacrist were performed by the doorkeepers ( ostiarii), and later by the treasurers and mansionarii. The Decreta ...

and the chaplain

A chaplain is, traditionally, a cleric (such as a Minister (Christianity), minister, priest, pastor, rabbi, purohit, or imam), or a laity, lay representative of a religious tradition, attached to a secularity, secular institution (such as a hosp ...

. A series of Priests Vicar assist the minor canons.

King's Almsmen

An establishment of six King's (or Queen's) Almsmen and women is supported by the abbey; they are appointed by royal warrant on the recommendation of the dean and theHome Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all national s ...

, attend Matins and Evensong on Sundays and do such duties as may be requested (in return for which they receive a small stipend); when on duty they wear a distinctive red gown with a crowned rose badge on the left shoulder. From the late 18th until the late 20th century the almsmen were usually ex-servicemen, but today they are mostly retired employees of the abbey. Historically, the King's Almsmen and women were retired Crown servants residing in the Royal Almshouse at Westminster, which had been established by Henry VII in connection with his building of the new Lady Chapel, to support the priests of his chantry

A chantry is an ecclesiastical term that may have either of two related meanings:

# a chantry service, a Christian liturgy of prayers for the dead, which historically was an obiit, or

# a chantry chapel, a building on private land, or an area i ...

by offering daily prayer. The Royal Almshouse survived the Dissolution of the Monasteries, but was demolished for road-widening in 1779.

Burials and memorials

Henry III rebuilt the abbey in honour of a royal saint, Edward the Confessor, whose relics were placed in ashrine

A shrine ( la, scrinium "case or chest for books or papers"; Old French: ''escrin'' "box or case") is a sacred or holy space dedicated to a specific deity, ancestor, hero, martyr, saint, daemon, or similar figure of respect, wherein they ...

in the sanctuary. Henry III was interred nearby, as were many of the Plantagenet

The House of Plantagenet () was a royal house which originated from the lands of Anjou in France. The family held the English throne from 1154 (with the accession of Henry II at the end of the Anarchy) to 1485, when Richard III died in ...

kings of England, their wives and other relatives. Until the death of George II George II or 2 may refer to:

People

* George II of Antioch (seventh century AD)

* George II of Armenia (late ninth century)

* George II of Abkhazia (916вҖ“960)

* Patriarch George II of Alexandria (1021вҖ“1051)

* George II of Georgia (1072вҖ“1089) ...

in 1760, most kings and queens were buried in the abbey. Some notable exceptions are Henry VI, Edward IV, Henry VIII and Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742вҖ“814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226вҖ“1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

who are buried in St George's Chapel at Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle is a royal residence at Windsor in the English county of Berkshire. It is strongly associated with the English and succeeding British royal family, and embodies almost a millennium of architectural history.

The original c ...

. Other exceptions include Edward II (buried at Gloucester Cathedral), John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

(buried at Worcester Cathedral

Worcester Cathedral is an Anglican cathedral in Worcester, in Worcestershire, England, situated on a bank overlooking the River Severn. It is the seat of the Bishop of Worcester. Its official name is the Cathedral Church of Christ and the Bles ...

), Henry IV (buried at Canterbury Cathedral

Canterbury Cathedral in Canterbury, Kent, is one of the oldest and most famous Christian structures in England. It forms part of a World Heritage Site. It is the cathedral of the Archbishop of Canterbury, currently Justin Welby, leader of the ...

), Richard III (now buried at Leicester Cathedral

The Cathedral Church of Saint Martin, Leicester, commonly known as Leicester Cathedral, is a Church of England cathedral in Leicester, England and the seat of the Bishop of Leicester. The church was elevated to a collegiate church in 192 ...

), and the ''de facto'' queen Lady Jane Grey (buried in the chapel of St Peter ad Vincula in the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is sep ...

). More recently, monarchs have been buried either in St George's Chapel or at the Frogmore Royal Burial Ground to the east of Windsor Castle.

From the Middle Ages, aristocrats were buried inside chapels, while monks and other people associated with the abbey were buried in the cloister

A cloister (from Latin ''claustrum'', "enclosure") is a covered walk, open gallery, or open arcade running along the walls of buildings and forming a quadrangle or garth. The attachment of a cloister to a cathedral or church, commonly against a ...

s and other areas. One of them was Geoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer (; вҖ“ 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for ''The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He wa ...

, who was employed as master of the King's Works and had apartments in the abbey. Other poets, writers and musicians were buried or memorialised around Chaucer in what became known as Poets' Corner

Poets' Corner is the name traditionally given to a section of the South Transept of Westminster Abbey in the City of Westminster, London because of the high number of poets, playwrights, and writers buried and commemorated there.

The first poe ...

. Abbey musicians such as Henry Purcell were also buried in their place of work.

Subsequently, it became one of Britain's most significant honours to be buried or commemorated in the abbey. The practice of burying national figures in the abbey began under Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

with the burial of Admiral Robert Blake Robert Blake may refer to:

Sportspeople

* Bob Blake (American football) (1885вҖ“1962), American football player

* Robbie Blake (born 1976), English footballer

* Bob Blake (ice hockey) (1914вҖ“2008), American ice hockey player

* Rob Blake (born 19 ...

in 1657 (although he was subsequently reburied outside). The practice spread to include generals, admirals, politicians, doctors and scientists such as Sir Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 вҖ“ 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author (described in his time as a "natural philosopher"), widely recognised as one of the grea ...

(buried on 4 April 1727), Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 вҖ“ 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

(buried on 26 April 1882), and Stephen Hawking (ashes interred on 15 June 2018). Another was William Wilberforce

William Wilberforce (24 August 175929 July 1833) was a British politician, philanthropist and leader of the movement to abolish the slave trade. A native of Kingston upon Hull, Yorkshire, he began his political career in 1780, eventually becom ...

, who led the movement to abolish slavery in the United Kingdom and the Plantations, buried on 3 August 1833. Wilberforce was buried in the north transept, close to his friend, the former prime minister, William Pitt the Younger

William Pitt the Younger (28 May 175923 January 1806) was a British statesman, the youngest and last prime minister of Great Britain (before the Acts of Union 1800) and then first prime minister of the United Kingdom (of Great Britain and Ire ...

.

During the early 20th century it became increasingly common to bury cremated

Cremation is a method of final disposition of a dead body through burning.

Cremation may serve as a funeral or post-funeral rite and as an alternative to burial. In some countries, including India and Nepal, cremation on an open-air pyre i ...

remains rather than coffins in the abbey. In 1905, the actor Sir Henry Irving

Sir Henry Irving (6 February 1838 вҖ“ 13 October 1905), christened John Henry Brodribb, sometimes known as J. H. Irving, was an English stage actor in the Victorian era, known as an actor-manager because he took complete responsibility ( ...

was cremated and his ashes buried in Westminster Abbey, thereby becoming the first person to be cremated before interment at the abbey. The majority of interments are of cremated remains, but some burials still take place вҖ“ Frances Challen, wife of Sebastian Charles, Canon of Westminster

The Dean and Chapter of Westminster are the ecclesiastical governing body of Westminster Abbey, a collegiate church of the Church of England and royal peculiar in Westminster, Greater London. They consist of the dean and several canons meeting in ...

, was buried alongside her husband in the south choir aisle in 2014. Members of the Percy family

The English surname Percy is of Norman origin, coming from Normandy to England, United Kingdom. It was from the House of Percy, Norman lords of Northumberland, derives from the village of Percy-en-Auge in Normandy. From there, it came into use ...

have a family vault, The Northumberland Vault, in St Nicholas's chapel within the abbey.

On the floor, just inside the Great West Door, in the centre of the nave, is the tomb of The Unknown Warrior

The British grave of the Unknown Warrior (often known as 'The Tomb of the Unknown Warrior') holds an unidentified member of the British armed forces killed on a European battlefield during the First World War.Hanson, Chapters 23 & 24 He was gi ...

, an unidentified British soldier killed on a European battlefield during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. He was buried in the abbey on 11 November 1920. This grave is the only one in the abbey on which it is forbidden to walk.

At the east end of the Lady Chapel is a memorial chapel to the airmen of the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

who were killed in the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countriesвҖ”including all of the great powersвҖ”forming two opposin ...

. It incorporates a memorial window to the Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain, also known as the Air Battle for England (german: die Luftschlacht um England), was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defende ...

, which replaces an earlier Tudor stained glass window destroyed in the war.

On 6 September 1997 the formal, though not state

On 6 September 1997 the formal, though not state funeral of Diana, Princess of Wales

The funeral of Diana, Princess of Wales, started on Saturday 6 September 1997 at 9:08am in London, when the tenor bell of Westminster Abbey started tolling to signal the departure of the cortГЁge from Kensington Palace. The coffin was carried ...

, was held. It was a royal ceremonial funeral including royal pageantry and Anglican funeral liturgy. A second public service was held on Sunday at the demand of the people. The burial occurred privately on 6 September on the grounds of her family estate, Althorp

Althorp (popularly pronounced ) is a Grade I listed stately home and estate in the civil parish of Althorp, in West Northamptonshire, England of about . By road it is about northwest of the county town of Northampton and about northwest of ...

, on a private island.

In 1998, ten vacant statue niches on the façade above the Great West Door were filled with representatives 20th-century Christian martyrs of various denominations. Those commemorated are Maximilian Kolbe

Maximilian Maria Kolbe (born Raymund Kolbe; pl, Maksymilian Maria Kolbe; 1894вҖ“1941) was a Polish Catholic priest and Conventual Franciscan friar who volunteered to die in place of a man named Franciszek Gajowniczek in the German death camp ...

, Manche Masemola

Manche Masemola (1913вҖ“1928) was a South African Christian martyr.

Early life

Masemola was born in Marishane, a small village near Jane Furse, in South Africa. She lived with her parents, two older brothers, a sister, and a cousin. German ...

, Janani Luwum

Janani Jakaliya Luwum (c. 1922 вҖ“ 17 February 1977) was the archbishop of the Church of Uganda from 1974 to 1977 and one of the most influential leaders of the modern church in Africa. He was arrested in February 1977 and died shortly after. A ...

, Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna

Grand may refer to:

People with the name

* Grand (surname)

* Grand L. Bush (born 1955), American actor

* Grand Mixer DXT, American turntablist

* Grand Puba (born 1966), American rapper

Places

* Grand, Oklahoma

* Grand, Vosges, village and co ...

, Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 вҖ“ April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

, Г“scar Romero

Г“scar Arnulfo Romero y GaldГЎmez (15 August 1917 вҖ“ 24 March 1980) was a prelate of the Catholic Church in El Salvador. He served as Auxiliary Bishop of the Archdiocese of San Salvador, the Titular Bishop of Tambeae, as Bishop of Santiago ...

, Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Dietrich Bonhoeffer (; 4 February 1906 вҖ“ 9 April 1945) was a German Lutheran pastor, theologian and anti-Nazi dissident who was a key founding member of the Confessing Church. His writings on Christianity's role in the secular world have ...

, Esther John

Esther John ( ur, ), born Qamar Zia (Urdu: ), on 14 December 1929; died 2 February 1960) was a Pakistani Christian nurse who was murdered in 1960 for her efforts in Christian evangelism. She was subsequently recognized as a Christian martyr. In ...

, Lucian Tapiedi

Lucian Tapiedi ( вҖ“ 1942) was a Papua New Guinea, Papuan Anglicanism, Anglican teacher who was one of the "New Guinea Martyrs." The Martyrs were eight Anglican clergy, teachers, and medical missionaries killed by the Empire of Japan, Japanese in ...

, and Wang Zhiming.

Schools

Westminster School

(God Gives the Increase)

, established = Earliest records date from the 14th century, refounded in 1560

, type = Public school Independent day and boarding school

, religion = Church of England

, head_label = Hea ...

is located in the precincts of the abbey where it was founded by the Benedictine monks. Separately, Westminster Abbey Choir School

Westminster Abbey Choir School is a boarding preparatory school for boys in Westminster, London and the only remaining choir school in the United Kingdom which exclusively educates choristers (i.e. only choirboys attend the school). It is loca ...

is also located within the abbey grounds and exclusively educates the choirboys who sing for abbey services.

Music

Westminster Abbey is renowned for its choral tradition, and the repertoire of

Westminster Abbey is renowned for its choral tradition, and the repertoire of Anglican church music

Anglican church music is music that is written for Christian worship in Anglican religious services, forming part of the liturgy. It mostly consists of pieces written to be sung by a church choir, which may sing '' a cappella'' or accompanie ...

is heard in daily worship, particularly at the service of Choral Evensong

Evensong is a church service traditionally held near sunset focused on singing psalms and other biblical canticles. In origin, it is identical to the canonical hour of vespers. Old English speakers translated the Latin word as , which beca ...

. The abbey choir consists of 12 professional adults and up to thirty boy choristers who all attend Westminster Abbey Choir School

Westminster Abbey Choir School is a boarding preparatory school for boys in Westminster, London and the only remaining choir school in the United Kingdom which exclusively educates choristers (i.e. only choirboys attend the school). It is loca ...

.

Organ

The organ was built byHarrison & Harrison

Harrison & Harrison Ltd is a British company that makes and restores pipe organs, based in Durham and established in Rochdale in 1861. It is well known for its work on instruments such as King's College, Cambridge, Westminster Abbey, and the ...

in 1937, then with four manuals and 84 speaking stops, and was used for the first time at the coronation of George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 вҖ“ 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death in 1952. He was also the last Emperor of I ...

. Some pipework from the previous Hill organ of 1848 was revoiced and incorporated in the new scheme. The two organ cases, designed and built in the late 19th century by John Loughborough Pearson

John Loughborough Pearson (5 July 1817 вҖ“ 11 December 1897) was a British Gothic Revival architect renowned for his work on churches and cathedrals. Pearson revived and practised largely the art of vaulting, and acquired in it a proficiency ...

, were re-instated and coloured in 1959.

In 1982 and 1987, Harrison & Harrison enlarged the organ under the direction of the then abbey organist Simon Preston

Simon John Preston (4 August 1938 вҖ“ 13 May 2022) was an English organist, conductor, and composer.

...

to include an additional Lower Choir Organ and a Bombarde Organ: the current instrument now has five manuals and 109 speaking stops. In 2006, the console of the organ was refurbished by Harrison & Harrison, and space was prepared for two additional 16 ft stops on the Lower Choir Organ and the Bombarde Organ.

The current Organist and Master of the choristers, James O'Donnell, has been in post since 2000.

...

Bells

The bells at the abbey were overhauled in 1971. Thering

Ring may refer to:

* Ring (jewellery), a round band, usually made of metal, worn as ornamental jewelry

* To make a sound with a bell, and the sound made by a bell

:(hence) to initiate a telephone connection

Arts, entertainment and media Film and ...

is now made up of ten bells, hung for change ringing, cast in 1971 by the Whitechapel Bell Foundry

The Whitechapel Bell Foundry was a business in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. At the time of the closure of its Whitechapel premises, it was the oldest manufacturing company in Great Britain. The bell foundry primarily made church bells ...

, tuned to the notes: F#, E, D, C#, B, A, G, F#, E and D. The Tenor bell in D (588.5 Hz) has a weight of 30 cwt, 1 qtr, 15 lb (3403 lb or 1544 kg).WestminsterвҖ”Collegiate Church of S Peter (Westminster Abbey),

Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers

''Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers'' (known to ringers as ''Dove's Guide'' or simply ''Dove'') is the standard reference to the rings of bells hung for English-style full circle ringing. The vast majority of these "towers" are in England a ...

, 25 October 2006. Retrieved 16 October 2008.

In addition there are two service bells, cast by Robert Mot, in 1585 and 1598 respectively, a Sanctus bell cast in 1738 by Richard Phelps and Thomas Lester and two unused bellsвҖ”one cast about 1320, and a second cast in 1742, by Thomas Lester. The two service bells and the 1320 bell, along with a fourth small silver "dish bell", kept in the refectory, have been noted as being of historical importance by the Church Buildings Council of the Church of England.

Chapter house

The chapter house was built concurrently with the east parts of the abbey under Henry III, between about 1245 and 1253. It was

The chapter house was built concurrently with the east parts of the abbey under Henry III, between about 1245 and 1253. It was restored

''Restored'' is the fourth

studio album by American contemporary Christian music musician Jeremy Camp. It was released on November 16, 2004 by BEC Recordings.

Track listing

Standard release

Enhanced edition

Deluxe gold edition

Standard ...

by Sir George Gilbert Scott in 1872. The entrance is approached from the east cloister walk and includes a double doorway with a large tympanum above.

Inner and outer vestibules lead to the octagonal chapter house. It is built in a Geometrical Gothic style with an octagonal crypt below and a pier of eight shafts carries the vaulted ceiling. To the sides are blind arcading, remains of 14th-century paintings and numerous stone benches above which are innovatory large 4-light quatre-foiled windows. These are virtually contemporary with the Sainte-Chapelle

The Sainte-Chapelle (; en, Holy Chapel) is a royal chapel in the Gothic style, within the medieval Palais de la CitГ©, the residence of the Kings of France until the 14th century, on the ГҺle de la CitГ© in the River Seine in Paris, France.

...

, Paris.

The chapter house has an original mid-13th-century tiled pavement. A door made with wood from a single tree grown in Hainault Forest

Hainault Forest Country Park is a Country Park located in Greater London, with portions in: Hainault in the London Borough of Redbridge; the London Borough of Havering; and in the Lambourne parish of the Epping Forest District in Essex.

Geograp ...

, within the vestibule, dates from around 1050 and is one of the oldest in Britain. The exterior includes flying buttresses added in the 14th century and a leaded tent-lantern roof on an iron frame designed by Scott. The chapter house was originally used in the 13th century by Benedictine monks for daily meetings. It later became a meeting place of the King's Great Council and the Commons, predecessors of Parliament.

The Pyx Chamber formed the undercroft of the monks' dormitory. It dates to the late 11th century and was used as a monastic and royal treasury. The outer walls and circular piers are of 11th-century date, several of the capitals were enriched in the 12th century and the stone altar added in the 13th century. The term ''pyx'' refers to the boxwood chest in which coins were held and presented to a jury during the Trial of the Pyx

The Trial of the Pyx () is a judicial ceremony in the United Kingdom to ensure that newly minted coins from the Royal Mint conform to their required dimensional and fineness specifications. Although coin quality is now tested throughout the year ...

, in which newly minted coins were presented to ensure they conformed to the required standards.

The chapter house and Pyx Chamber at Westminster Abbey are in the guardianship of English Heritage

English Heritage (officially the English Heritage Trust) is a charity that manages over 400 historic monuments, buildings and places. These include prehistoric sites, medieval castles, Roman forts and country houses.

The charity states that i ...

, but under the care and management of the Dean and Chapter of Westminster.

Museum

TheWestminster Abbey Museum

The Westminster Abbey Museum was located in the 11th-century vaulted undercroft beneath the former monks' dormitory in Westminster Abbey, London, England. This was located in one of the oldest areas of the abbey, dating back almost to the foundati ...

was located in the 11th-century vaulted

In architecture, a vault (French ''voГ»te'', from Italian ''volta'') is a self-supporting arched form, usually of stone or brick, serving to cover a space with a ceiling or roof. As in building an arch, a temporary support is needed while ring ...

undercroft beneath the former monks' dormitory. This was one of the oldest areas of the abbey, dating back almost to the foundation of the church by Edward the Confessor in 1065. This space had been used as a museum since 1908Trowles 2008, p. 156 but was closed to the public in June 2018, when it was replaced as a museum by the Queen's Diamond Jubilee Galleries, high up in the abbey's triforium

A triforium is an interior gallery, opening onto the tall central space of a building at an upper level. In a church, it opens onto the nave from above the side aisles; it may occur at the level of the clerestory windows, or it may be locat ...

.

Transport

See also

* Archdeacon of Westminster *Dean of Westminster

The Dean of Westminster is the head of the chapter at Westminster Abbey. Due to the Abbey's status as a Royal Peculiar, the dean answers directly to the British monarch (not to the Bishop of London as ordinary, nor to the Archbishop of Canterbu ...

* List of churches in London

* The Abbey (1995 TV series), ''The Abbey'' (a three-part BBC Television, BBC TV documentary written and hosted by playwright Alan Bennett)

Notes

References

* Bradley, S. and Nikolaus Pevsner, N. Pevsner (2003) ''The Buildings of England вҖ“ London 6: Westminster'', New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 105вҖ“207. * Mortimer, Richard, ed., ''Edward the Confessor: The Man and the Legend'', The Boydell Press, 2009. Eric Fernie, 'Edward the Confessor's Westminster Abbey', pp. 139вҖ“150. Warwick Rodwell, 'New Glimpses of Edward the Confessor's Abbey at Westminster', pp. 151вҖ“167. Richard Gem, Craftsmen and Administrators in the Building of the Confessor's Abbey', pp. 168вҖ“172. * Harvey, B. (1993) ''Living and Dying in England 1100вҖ“1540: The Monastic Experience'', Ford Lecture series, Oxford: Clarendon Press. * Henry Vollam Morton, Morton, H. V. [1951] (1988) ''In Search of London'', London: Methuen. * Trowles, T. (2008) ''Treasures of Westminster Abbey'', London: Scala.Further reading

* * *External links

*Walter Thornbury, Old and New London, Volume 3, 1878, pp. 394вҖ“462, British History Online

Westminster Abbey Article at EncyclopГҰdia Britannica

Historic images of Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey: A Peek Inside

вҖ“ slideshow by ''Life magazine, Life'' magazine

Keith Short вҖ“ Sculptor

Images of stone carving for Westminster Abbey

* [http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/15598a.htm/ Catholic Encyclopedia: Westminster Abbey]

Adrian FletcherвҖҷs Paradoxplace Westminster Abbey PagesвҖ”Photos

* A panorama of Westminster Abbey in daytime вҖ

version

Westminster Abbey on Twitter

Audio Guide of Westminster Abbey

{{Authority control Westminster Abbey, Churches completed in 1745 Christian monasteries established in the 10th century Church of England church buildings in the City of Westminster, Abbey Collegiate churches in England Coronation church buildings English Gothic architecture in Greater London Gothic architecture in England Grade I listed churches in the City of Westminster Nicholas Hawksmoor buildings Monasteries in London Religion in the City of Westminster, Abbey Royal Peculiars, London, Westminster Abbey, Abbey Tourist attractions in the City of Westminster, Abbey World Heritage Sites in London 13th-century architecture in the United Kingdom Edward Blore buildings Burial sites of the House of Tudor Burial sites of the House of Stuart Former cathedrals in London 1st-millennium establishments in England Burial sites of the House of Hanover Monasteries dissolved under the English Reformation