Wally Hammond on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Walter Reginald Hammond (19 June 1903 – 1 July 1965) was an English

Hammond made his first-class debut for Gloucestershire in August 1920. Although his first four

Hammond made his first-class debut for Gloucestershire in August 1920. Although his first four

In the winter of 1928–29, Hammond toured Australia with the M.C.C. The side was a strong one which overpowered Australia, winning the five-match series 4–1. Hammond was remarkably successful in his first campaign for

In the winter of 1928–29, Hammond toured Australia with the M.C.C. The side was a strong one which overpowered Australia, winning the five-match series 4–1. Hammond was remarkably successful in his first campaign for

''Wisden'' described Hammond's campaign as successful, although he failed to reach the heights of his previous tour. In the Tests, Hammond scored 440 runs (average 55.00) and took nine wickets (average 32.33), while scoring 948 runs (average 55.76) and taking 20 wickets (average 28.90) in all first-class matches. Although ''Wisden'' said that Hammond accomplished little with the ball, team manager Plum Warner praised his bowling, claiming that during the first Test it was comparable to that of revered former England bowler Sydney Barnes. His best performance was in a match against

''Wisden'' described Hammond's campaign as successful, although he failed to reach the heights of his previous tour. In the Tests, Hammond scored 440 runs (average 55.00) and took nine wickets (average 32.33), while scoring 948 runs (average 55.76) and taking 20 wickets (average 28.90) in all first-class matches. Although ''Wisden'' said that Hammond accomplished little with the ball, team manager Plum Warner praised his bowling, claiming that during the first Test it was comparable to that of revered former England bowler Sydney Barnes. His best performance was in a match against

As the 1936 season began, Hammond remained weak from the recent removal of his tonsils. Returning to cricket too soon, he was in poor form; he took a longer rest, which caused him to miss the first of three Tests against India. It was July before he felt fully well. In all first-class cricket that season, Hammond scored 2,107 runs, averaging 56.94, and took 41 wickets. In county cricket, Gloucestershire appointed a new captain,

As the 1936 season began, Hammond remained weak from the recent removal of his tonsils. Returning to cricket too soon, he was in poor form; he took a longer rest, which caused him to miss the first of three Tests against India. It was July before he felt fully well. In all first-class cricket that season, Hammond scored 2,107 runs, averaging 56.94, and took 41 wickets. In county cricket, Gloucestershire appointed a new captain,

first-class cricket

First-class cricket, along with List A cricket and Twenty20 cricket, is one of the highest-standard forms of cricket. A first-class match is one of three or more days' scheduled duration between two sides of eleven players each and is officiall ...

er who played for Gloucestershire

Gloucestershire ( abbreviated Glos) is a county in South West England. The county comprises part of the Cotswold Hills, part of the flat fertile valley of the River Severn and the entire Forest of Dean.

The county town is the city of ...

in a career that lasted from 1920 to 1951. Beginning as a professional, he later became an amateur

An amateur () is generally considered a person who pursues an avocation independent from their source of income. Amateurs and their pursuits are also described as popular, informal, self-taught, user-generated, DIY, and hobbyist.

History

...

and was appointed captain of England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

. Primarily a middle-order batsman, ''Wisden Cricketers' Almanack

''Wisden Cricketers' Almanack'', or simply ''Wisden'', colloquially the Bible of Cricket, is a cricket reference book published annually in the United Kingdom. The description "bible of cricket" was first used in the 1930s by Alec Waugh in a ...

'' described him in his obituary as one of the four best batsmen in the history of cricket. He was considered to be the best English batsman of the 1930s by commentators and those with whom he played; they also said that he was one of the best slip fielders ever. Hammond was an effective fast-medium pace bowler and contemporaries believed that if he had been less reluctant to bowl, he could have achieved even more with the ball than he did.

In a Test

Test(s), testing, or TEST may refer to:

* Test (assessment), an educational assessment intended to measure the respondents' knowledge or other abilities

Arts and entertainment

* ''Test'' (2013 film), an American film

* ''Test'' (2014 film), ...

career spanning 85 matches, he scored 7,249 runs and took 83 wickets. Hammond captained England in 20 of those Tests, winning four, losing three, and drawing 13. His career aggregate of runs was the highest in Test cricket until surpassed by Colin Cowdrey in 1970; his total of 22 Test centuries remained an English record until Alastair Cook

Sir Alastair Nathan Cook (born 25 December 1984) is an English cricketer who plays for Essex County Cricket Club, and played for England in all international formats from 2006 to 2018. A former captain of the England Test and One-Day Intern ...

surpassed it in December 2012. In 1933, he set a record for the highest individual Test innings of 336 not out

In cricket, a batter is not out if they come out to bat in an innings and have not been dismissed by the end of an innings. The batter is also ''not out'' while their innings is still in progress.

Occurrence

At least one batter is not out at ...

, surpassed by Len Hutton

Sir Leonard Hutton (23 June 1916 – 6 September 1990) was an English cricketer. He played as an opening batsman for Yorkshire County Cricket Club from 1934 to 1955 and for England in 79 Test matches between 1937 and 1955. '' Wisden Cricke ...

in 1938. In all first-class cricket, he scored 50,551 runs and 167 centuries, respectively the seventh and third highest totals by a first-class cricketer.

Although Hammond began his career in 1920, he was required to wait until 1923 before he could play full-time, after his qualification to play for Gloucestershire was challenged. His potential was spotted immediately and after three full seasons, he was chosen to visit the West Indies in 1925–26 as a member of a Marylebone Cricket Club

Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) is a cricket club founded in 1787 and based since 1814 at Lord's Cricket Ground, which it owns, in St John's Wood, London. The club was formerly the governing body of cricket retaining considerable global influe ...

touring party, but contracted a serious illness on the tour. He began to score heavily after his recovery in 1927 and was selected for England. In the 1928–29 series against Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by ...

he scored 905 runs, then a record aggregate for a Test series. He dominated county cricket in the 1930s and, despite a mid-decade slump in Test form, was made captain of England in 1938. He continued as captain after the Second World War, but his health had deteriorated and he retired from first-class cricket after an unsuccessful tour of Australia in 1946–47. He appeared in two more first-class matches in the early 1950s.

Hammond was married twice, divorcing his first wife in acrimonious circumstances, and had a reputation for infidelity. His relationships with other players were difficult; teammates and opponents alike found him hard to get along with. He was unsuccessful in business dealings and failed to establish a successful career once he retired from cricket. He moved to South Africa in the 1950s in an attempt to start a business, but this came to nothing. As a result, he and his family struggled financially. Shortly after beginning a career as a sports administrator, he was involved in a serious car crash in 1960 which left him frail. He died of a heart attack in 1965.

Early life and career

Childhood and school life

Hammond was born on 19 June 1903 inDover

Dover () is a town and major ferry port in Kent, South East England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies south-east of Canterbury and east of Maids ...

in Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

. His parents, William—a bombardier in the Royal Garrison Artillery

The Royal Garrison Artillery (RGA) was formed in 1899 as a distinct arm of the British Army's Royal Regiment of Artillery serving alongside the other two arms of the Regiment, the Royal Field Artillery (RFA) and the Royal Horse Artillery (R ...

—and Marion Hammond (née Crisp), lived in the married quarters at Dover Castle

Dover Castle is a medieval castle in Dover, Kent, England and is Grade I listed. It was founded in the 11th century and has been described as the "Key to England" due to its defensive significance throughout history. Some sources say it is th ...

where Walter was born. They had wed the previous December.Foot, p. 59. Hammond spent his early years in Dover, often playing cricket. When he was five years old, his father was posted to Hong Kong to serve on the China Station and promoted to sergeant. The family remained there until 1911, followed by a posting to Malta until 1914. Hammond later recalled playing cricket in Malta using improvised equipment, including a soldier's old bat which he believed taught him to strike the ball powerfully.

When the First World War broke out, the Hammonds returned to England with the rest of the 46th Company of the Royal Garrison Artillery. William was subsequently posted to France where, promoted to major

Major ( commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicato ...

, he was killed near Amiens

Amiens (English: or ; ; pcd, Anmien, or ) is a city and commune in northern France, located north of Paris and south-west of Lille. It is the capital of the Somme department in the region of Hauts-de-France. In 2021, the population of ...

in 1918. Marion settled in Southsea and sent Walter to The Portsmouth Grammar School

The Portsmouth Grammar School is a co-educational independent day school in Portsmouth, England, located in the historic part of Portsmouth. It was founded in 1732 as a boys' school and is located on Portsmouth High Street.

History

In 1732, ...

, before moving him in 1918 to board

Board or Boards may refer to:

Flat surface

* Lumber, or other rigid material, milled or sawn flat

** Plank (wood)

** Cutting board

** Sounding board, of a musical instrument

* Cardboard (paper product)

* Paperboard

* Fiberboard

** Hardboard, a ty ...

at Cirencester Grammar School, believing that he would benefit from living away from home and hoping to encourage a career in farming.Howat, pp. 5–6. He did not enjoy an easy relationship with his mother, often staying with friends during holidays in preference to returning home.

At both Portsmouth and Cirencester, Hammond excelled at sports including cricket (playing for the Portsmouth Grammar School second eleven), football and fives. At Cirencester, he played football for the school first eleven in his first term. He quickly reached the school cricket first eleven, where he outperformed the other players and became captain in his second season; his headmaster, quickly spotting his potential, encouraged him. His first century was scored in a match against a parents' team from the school. In an inter-house match, he scored 365 not out, albeit against very weak bowling. These achievements brought him some local acclaim. Hammond enjoyed less success in the classroom; his marks were usually low, and he preferred to be out playing cricket.Foot, p. 63.

Leaving Cirencester in July 1920, Hammond planned to go to Winchester Agricultural College, following the path into farming mapped out by his mother. However, his plans changed when his headmaster wrote to the captain of Gloucestershire

Gloucestershire ( abbreviated Glos) is a county in South West England. The county comprises part of the Cotswold Hills, part of the flat fertile valley of the River Severn and the entire Forest of Dean.

The county town is the city of ...

, Foster Robinson, reporting Hammond's school cricket record and suggesting that they take a look at him. Hammond, who scored a century in his first appearance in adult cricket days after leaving school, played in a trial match for the Gloucestershire Club and Ground, scoring 60 runs, taking two wickets and impressing the local press. Subsequently, two members of Gloucestershire's committee visited Hammond's mother in an attempt to sign him for the club. Hammond's mother was initially reluctant, but his eagerness finally convinced her and he signed a professional contract.

First years with Gloucestershire

Hammond made his first-class debut for Gloucestershire in August 1920. Although his first four

Hammond made his first-class debut for Gloucestershire in August 1920. Although his first four inning

In baseball, softball, and similar games, an inning is the basic unit of play, consisting of two halves or frames, the "top" (first half) and the "bottom" (second half). In each half, one team bats until three outs are made, with the other tea ...

s yielded only 27 runs, the local press saw enough to predict a great future for him. He spent the winter working on a farm on the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the largest and second-most populous island of England. Referred to as 'The Island' by residents, the Is ...

, then moved to Bristol

Bristol () is a City status in the United Kingdom, city, Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, Bristol, River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Glouces ...

for the start of the 1921 English cricket season. Playing only two first-class matches in 1921, both against the powerful Australian tourists, Hammond scored two runs in three innings, overwhelmed by fast bowler Jack Gregory. In between these games, Gloucestershire arranged his appointment as assistant coach at Clifton College

''The spirit nourishes within''

, established = 160 years ago

, closed =

, type = Public schoolIndependent boarding and day school

, religion = Christian

, president =

, head_label = Head of College

, hea ...

, Bristol, where he worked on his batting technique with former county cricketers John Tunnicliffe and George Dennett

Edward George Dennett (27 April 1879 – 15 September 1937) was a left arm spinner for Gloucestershire County Cricket Club between 1903 and 1926, and from his figures could be considered one of the best bowlers never to play Test cricket. Ow ...

.

Gloucestershire gave Hammond an extended run at the start of the 1922 season. He played five matches without passing 32 runs in an innings at a batting average of under ten. He did not have the opportunity to improve his record as Lord Harris

Colonel George Robert Canning Harris, 4th Baron Harris, (3 February 1851 – 24 March 1932), generally known as Lord Harris, was a British colonial administrator and Governor of Bombay. He was also an English amateur cricketer, mainly active f ...

, the Marylebone Cricket Club

Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) is a cricket club founded in 1787 and based since 1814 at Lord's Cricket Ground, which it owns, in St John's Wood, London. The club was formerly the governing body of cricket retaining considerable global influe ...

(M.C.C.) treasurer, noticed that Hammond was born in Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

. He had not resided in Gloucestershire long enough to be eligible to play for the team under County Championship

The County Championship (referred to as the LV= Insurance County Championship for sponsorship reasons) is the domestic first-class cricket competition in England and Wales and is organised by the England and Wales Cricket Board (ECB). It b ...

rules, and was barred for the rest of the season. The press criticised the ruling for interrupting the career of a player seen as very promising, despite his lack of success thus far. Hammond spent the rest of the summer, which he later described as the most miserable of his life, watching county games, although Gloucestershire continued to pay him in full.Hammond, p. 20.

Football career

In the winter of 1921–22, Hammond, needing work, signed to play professional football forBristol Rovers F.C.

Bristol Rovers Football Club are a professional football club in Bristol, England. They compete in League One, the third tier of the English football league system.

They play home matches at the Memorial Stadium in Horfield, they have be ...

in Division Three South

The Third Division South of The Football League was a tier in the English football league system from 1921 to 1958. It ran in parallel with the Third Division North with clubs elected to the League or relegated from Division Two allocated to on ...

, following his success at school and in the Bristol Downs Football League. After some time in the reserves, he made four appearances for the first team that season. He played in ten games the following season, and four times in 1923–24. His usual position was on the right wing. Despite scoring twice in his career, he never showed much enthusiasm for the game and was cautious around tackles, mindful that his main career was cricket. He was criticised in the local press for his role in two defeats shortly before his final appearance. After he was left out of the team, he never played again and left the club, deciding that he could not play two sports professionally. Even so, the Rovers' trainer, Bert Williams, and manager, Andy Wilson, believed that Hammond, one of the fastest players they had seen at the club, would have had the potential to play international football.Howat, p. 17.

Making an impression

Conscious of the need to improve after his uncertain start to first-class cricket, Hammond scored his maiden first-class century in the first match of the 1923 season, making 110 and 92 opening the batting againstSurrey

Surrey () is a ceremonial county, ceremonial and non-metropolitan county, non-metropolitan counties of England, county in South East England, bordering Greater London to the south west. Surrey has a large rural area, and several significant ur ...

. He did not reach three figures again that season, but his performances and batting technique impressed several critics, such as cricket correspondent Neville Cardus, former England and Middlesex

Middlesex (; abbreviation: Middx) is a historic county in southeast England. Its area is almost entirely within the wider urbanised area of London and mostly within the ceremonial county of Greater London, with small sections in neighbour ...

captain Plum Warner, and ''The Times'' correspondent; Cardus described him as a future England player. In all first-class matches that season, Hammond scored 1,421 runs at an average of 27.86. With the ball, he took 18 first-class wickets at an average

In ordinary language, an average is a single number taken as representative of a list of numbers, usually the sum of the numbers divided by how many numbers are in the list (the arithmetic mean). For example, the average of the numbers 2, 3, 4, 7 ...

of 41.22, including figures of six for 59 against Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in western South East England on the coast of the English Channel. Home to two major English cities on its south coast, Southampton and Portsmouth, Hampshire ...

. Reviewing the season, '' Wisden''s correspondent declared that Hammond "has all the world before him and there is no telling how far he may go".Howat, p. 23.

Hammond reached 1,239 runs in 1924

Events

January

* January 12 – Gopinath Saha shoots Ernest Day, whom he has mistaken for Sir Charles Tegart, the police commissioner of Calcutta, and is arrested soon after.

* January 20– 30 – Kuomintang in China hold ...

, scoring a century against Somerset

( en, All The People of Somerset)

, locator_map =

, coordinates =

, region = South West England

, established_date = Ancient

, established_by =

, preceded_by =

, origin =

, lord_lieutenant_office =Lord Lieutenant of Somerset

, lor ...

and reaching fifty against Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, Essex

Essex () is a Ceremonial counties of England, county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the Riv ...

and Hampshire. In the final County Championship match of the season, against Middlesex, he scored 174 not out after Gloucestershire had been bowled out for 31 in their first innings. He finished the season with an average of 30.21 and supplemented his batting with 29 wickets. He improved on this record in 1925 with 1,818 runs at an average of 34.30 and 68 wickets at an average of just under 30, more than doubling his career aggregate of wickets. His bowling performances led critics to describe him as a potentially good all-rounder. Hammond was not satisfied with his batting form in 1925, but against Lancashire at Old Trafford, he scored 250 not out, repeatedly hooking the short-pitched bowling of Australian Test bowler Ted McDonald

Edgar Arthur "Ted" McDonald (6 January 1891 – 22 July 1937) was a cricketer who played for Tasmania, Victoria, Lancashire and Australia, as well as being an Australian rules footballer who played with Launceston Football Club, Essendon Foo ...

. Cardus described it as "one of the finest innings that can ever have been accomplished by a boy of his age". Over these two seasons, Hammond increasingly batted in the middle order

In cricket, the batting order is the sequence in which batters play through their team's innings, there always being two batters taking part at any one time. All eleven players in a team are required to bat if the innings is completed (i.e., if ...

, where he remained for most of his career.

Serious illness

Hammond's performances earned him selection for the M.C.C. winter tour of the West Indies in the 1925–26 season. At that time, such tours were popular with amateur cricketers, who were often chosen for social rather than cricketing reasons. The touring party contained only eight professionals, who were expected to do most of the bowling and provide the cricketing quality. The West Indies team did not have Test status, so no official internationals were scheduled, but a series of representative matches against a West Indian team were played. Rain disrupted much of the cricket, but Hammond enjoyed the experience. In first-class matches, he scored 732 runs at an average of 48.80, with two hundreds and two fifties, and took 20 wickets at an average of 28.65. He scored 238 not out in the first representative game against a West Indies side. Following the tour, he won praise from Warner and the captain of the M.C.C. team, Freddie Calthorpe, and was believed to be close to the full England side. Towards the end of the tour, Hammond fell seriously ill; according to him, a mosquito stung him in the groin area, close to a strain he had suffered, causing blood poisoning.Hammond, pp. 28–29. Playing againstJamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of Hispa ...

, he moved awkwardly and his teammates observed him to be in pain. He missed the remaining matches of the tour, and none of the doctors he saw were able to help. On the journey home, during which no doctor was available, his condition worsened, confining him to his cabin with a severe fever for most of the trip. The day after his arrival home, in April 1926, Hammond had the first of 12 operations at the nursing home to which he was taken. His condition worsened to the point where the doctors believed he would die; they considered amputating his leg, a suggestion vetoed by his mother out of concern for his career. Hammond later claimed that his illness remained a mystery to those treating him. A visit from Warner encouraged Hammond to believe recovery was possible, and he began a slow return to health about a month after his return to England. By July, he could watch Gloucestershire playing in Bristol, though he missed the entire 1926 season. No official announcement about Hammond's illness was made, other than to say he was in a nursing home. Although the cause of the illness was never made clear, David Foot

David K. Foot is a Canadian economist and demographer. Foot did his undergraduate work at the University of Western Australia and his graduate work in economics at Harvard University, where he was supervised by Martin Feldstein. Following his ...

has argued that it was syphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium '' Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms of syphilis vary depending in which of the four stages it presents (primary, secondary, latent, a ...

or a related sexually transmitted disease. He has also suggested that its treatment, which in the days before antibiotics probably involved mercury, adversely affected Hammond's subsequent character and personality, leading to moody and depressive behaviour. Rumours of this nature circulated among his contemporaries for many years before Foot published his theory. That winter, Hammond coached in South Africa, where it was felt the climate might aid his recovery.

Test cricketer

Test debut

On his return to first-class cricket in the 1927 season, Hammond made an immediate impact, becoming only the second man, after W. G. Grace, to score 1,000 runs in May, traditionally the first month of the English cricket season. This sequence included another effective performance against Lancashire, regarded by some observers as one of the best innings ever played. He scored 99 in the first innings and 187 in the second to ensure the match was drawn. He again hooked McDonald effectively, at one point hitting five consecutive fours.Howat, p. 30. Hammond played in the prestigious Gentlemen v Players match at Lord's for the first time, although he neither batted nor bowled, as well as two Test trials. Coming close to scoring 1,000 runs in June as well, he finished the season with 2,969 runs, including 12 centuries. His average of 69.04 was the fifth highest in first-class cricket. He won selection for the M.C.C. team that would tour South Africa in the winter and the accolade of being named one of theWisden Cricketers of the Year

The ''Wisden'' Cricketers of the Year are cricketers selected for the honour by the annual publication '' Wisden Cricketers' Almanack'', based primarily on their "influence on the previous English season". The award began in 1889 with the naming ...

.

While on tour in South Africa in 1927–28, Hammond did not dominate as expected. Still recovering from his illness, he was worn out from the strain of a long season. He showed good batting form, but once George Geary was injured, a strong but not fully representative side found itself short of bowling, forcing Hammond to play as an all-rounder.Foot, p. 109. In all first-class matches on the tour, he scored 908 runs at an average of 47.78, and took 27 wickets at an average of 23.85. His Test debut came in the first match of the series, as he scored a quick 51 in his only innings and took five wickets for 36 runs in the South African second innings. At one point, he took three wickets for no runs and his bowling was described by ''Wisden'' as a key factor in an England victory. His best innings came in the third Test as he reached 90. He had some good bowling spells, and in the fourth Test he removed both South African openers. An innings of 66 in the fifth and final Test left him with 321 runs at an average of 40.12 in his debut series, while his 15 wickets cost 26.60 runs each. All of Hammond's batting appearances were at number four in the order; of his 140 career Test innings, 118 were at number three or four. The series was drawn 2–2.

In the following season of 1928

Events January

* January – British bacteriologist Frederick Griffith reports the results of Griffith's experiment, indirectly proving the existence of DNA.

* January 1 – Eastern Bloc emigration and defection: Boris Bazhano ...

, Hammond scored 2,825 runs (average 65.69) with three double centuries, took 84 wickets (average 23.10), his highest total in a season, and held 79 catches, a single season record. These performances helped Gloucestershire to mount a rare but unsuccessful challenge for the County Championship.Howat, p. 34. At the Cheltenham

Cheltenham (), also known as Cheltenham Spa, is a spa town and borough on the edge of the Cotswolds in the county of Gloucestershire, England. Cheltenham became known as a health and holiday spa town resort, following the discovery of mineral s ...

festival, in six days, Hammond scored 362 runs, took 11 wickets and held 11 catches. Against Surrey, he scored a century in both innings and held ten catches, including six in the second innings, which remains a first-class record as of 2015. In the following match, against Worcestershire, Hammond scored 80. Bowling off-spin on a testing pitch, he then took nine wickets for 23, the best bowling figures of his career. He followed up with six for 105 as Worcestershire followed on.Foot, p. 90. He played in a Test trial and in the Gentlemen v Players match at Lord's for the second time, before participating in the three Test matches against the West Indies cricket team

The West Indies cricket team, nicknamed the Windies, is a multi-national men's cricket team representing the mainly English-speaking countries and territories in the Caribbean region and administered by Cricket West Indies. The players on ...

. While England won the series 3–0, Hammond had mixed success. Despite scores of 45 in the first Test and a careful 63 in the second, he made just 111 runs in the series at an average of 37.

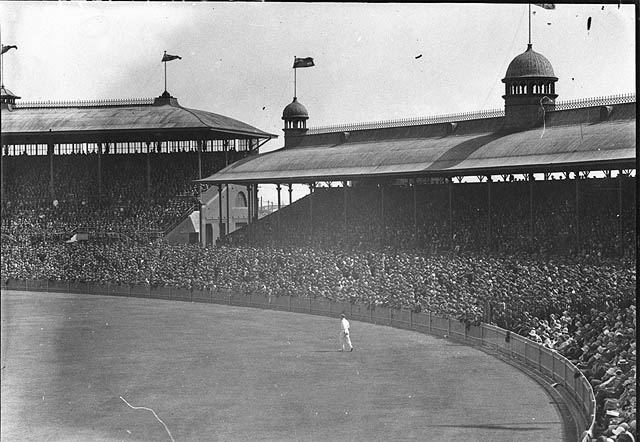

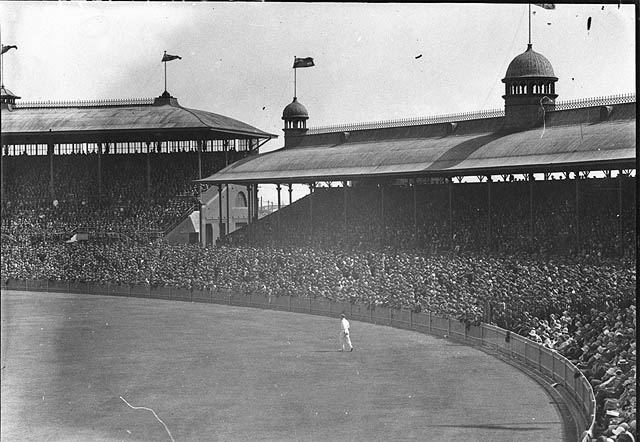

1928–29 tour of Australia

In the winter of 1928–29, Hammond toured Australia with the M.C.C. The side was a strong one which overpowered Australia, winning the five-match series 4–1. Hammond was remarkably successful in his first campaign for

In the winter of 1928–29, Hammond toured Australia with the M.C.C. The side was a strong one which overpowered Australia, winning the five-match series 4–1. Hammond was remarkably successful in his first campaign for The Ashes

The Ashes is a Test cricket series played between England and Australia. The term originated in a satirical obituary published in a British newspaper, '' The Sporting Times'', immediately after Australia's 1882 victory at The Oval, its first ...

. ''Wisden'' described his batting as a "series of triumphs". He scored 779 runs in five consecutive Test innings, totalling 905 runs at an average of 113.12 in the series, a record passed only by Don Bradman

Sir Donald George Bradman, (27 August 1908 – 25 February 2001), nicknamed "The Don", was an Australian international cricketer, widely acknowledged as the greatest batsman of all time. Bradman's career Test batting average of 99.94 has b ...

since. In all first-class matches, he scored 1,553 runs (average 91.35). However, except for one inspired spell in the final Test, in which he bowled the first three batsmen, ''Wisden'' described his bowling as disappointing. He began the tour with a century and a double century before the Test series. He scored 251 in a seven-hour innings in the second Test. This was his maiden Test century and the second highest Test score between England and Australia. In the next Test, Hammond scored 200 against an accurate attack, again taking around seven hours. In the fourth Test he scored 119 not out and then 177, in what ''Wisden'' judged his best innings of the tour due to his mastery of the bowlers and the difficult match situation when he came in to bat. Hammond had altered his usual batting style, playing more carefully and avoiding risk as runs were certain to come in the easy Australian batting conditions if a batsman did not get out. He eliminated the hook shot entirely from his repertoire and rarely played the cut shot. Unless the bowler bowled a bad ball, he limited his scoring between extra cover and midwicket, as the Australians unsuccessfully tried to block his shots in that area. ''Wisden'' stated that, even with his more cautious play, his batting on tour had shown skill and beauty.

Hammond married Dorothy Lister almost immediately after returning home, just before the 1929 season began. Gloucestershire's inspirational new captain, Bev Lyon, led another Gloucestershire challenge for the County Championship. He used Hammond's bowling less due to the emergence of Tom Goddard, but Hammond was less dominant with the bat than was expected. In first-class cricket, he scored 2,456 runs at an average of 64.63. He played in four of the five Tests against South Africa, missing the fourth due to injury; he also suffered an injury in the second Test which required him to use a runner

Running is a method of terrestrial locomotion allowing humans and other animals to move rapidly on foot. Running is a type of gait characterized by an aerial phase in which all feet are above the ground (though there are exceptions). This is ...

.Howat, p. 41. Adopting tactics similar to those with which he had success in Australia, he scored two centuries—an unbeaten 138 in the first Test, and a match-saving 101 not out in the final Test which gave England a 2–0 series victory. His only other innings over fifty was played in the third Test. He ended the series with 352 runs at an average of 58.66. At the time, critics considered him the best batsman in the world.Gibson, p. 172.

Career in the early 1930s

The 1930 season saw the Australians tour England, Bradman's first tour. Over five Tests, the young Australian scored 974 runs in an excellent batting display to break Hammond's record run aggregate and average set in the 1928–29 series. While Bradman dominated, Hammond found it very difficult to play theleg spin

Leg spin is a type of spin bowling in cricket. A leg spinner bowls right-arm with a wrist spin action. The leg spinner's normal delivery causes the ball to spin from right to left (from the bowler's perspective) when the ball bounces on the ...

bowling of Clarrie Grimmett, who dismissed him five times.Howat, p. 42.Hammond, p. 69. Hammond scored 306 runs at an average of 34.00, passing fifty just twice. He batted over five hours for a match-saving 113 in the third Test. On a difficult pitch and with little support, he made a hard-hitting 60 in the final Test in a losing cause. The visitors took the series 2–1, and the newspapers unfavourably compared Hammond's scoring with Bradman's. Later in the season, Hammond scored 89 for Gloucestershire in a tied match against the Australians which he described as the most exciting of his career. One player said that he had never seen Hammond as excited as he was at the conclusion of the game. In all first-class cricket that season, he scored 2,032 runs (average 53.47) and for Gloucestershire, he came top of the batting averages as the club finished second in the Championship. He took 30 wickets, including match figures of 12 for 74 against Glamorgan.

Hammond toured South Africa in the winter of 1930–31, in a weak M.C.C. side without some of the best English players.Howat, p. 44. The tourists were short of opening batsmen

In cricket, the batting order is the sequence in which batters play through their team's innings, there always being two batters taking part at any one time. All eleven players in a team are required to bat if the innings is completed (i.e., i ...

, frequently forcing Hammond into the role. Although successful, he brought a more wary approach than usual to his unaccustomed position. In all first-class cricket, he scored 1,045 runs (average 61.47). In the five-Test series, which South Africa won 1–0, he scored 517 runs (average 64.62), passing fifty five times in nine innings. A very cautious approach batting at number three saw Hammond score 49 and 63 in the first Test. Opening the batting in the second Test, he scored two fifties to save the game; he also kept wicket for a time following an injury to the regular wicketkeeper. Hammond continued to open in the third Test, playing more aggressively for 136 not out, before returning to number three and making 75 in the fourth Test. In the final Test, he opened both the batting and the bowling.

In 1931, Hammond increased his first-class wicket total to 47, and scored 1,781 runs at an average of 42.40. Although he remained a key batsman for Gloucestershire, both his aggregate and average fell, at least partly due to wet weather that often led to difficult batting conditions. In the three Tests against New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island coun ...

, their first in England, he made an attacking century in the second Test, England's only victory. He did not pass fifty in the rest of the series, ending the victorious campaign with 169 runs at an average of 56.33. In 1932

Events January

* January 4 – The British authorities in India arrest and intern Mahatma Gandhi and Vallabhbhai Patel.

* January 9 – Sakuradamon Incident: Korean nationalist Lee Bong-chang fails in his effort to assassinate Emperor Hir ...

, Hammond was appointed vice-captain of Gloucestershire, but it was noted in ''Wisden'' that he sometimes failed to inspire his team. Hammond himself felt unable, as a new captain, to take the same risks that Lyon had done. He scored 2,528 runs (average 56.17), including his then highest score of 264, and his first hundred for the Players against the Gentlemen. He also took 53 wickets.

Bodyline tour

Hammond was selected for the M.C.C. tour of Australia in 1932–33. Known as the Bodyline series, it became notorious for the controversial English tactic of bowling short on the line ofleg stump

In cricket, the stumps are the three vertical posts that support the bails and form the wicket. ''Stumping'' or ''being stumped'' is a method of dismissing a batsman.

The umpire ''calling stumps'' means the play is over for the day.

Part of t ...

, making the ball rise towards the batsman's body to create deflections that could be caught by leg-side fielders. Hammond, one of the first players selected, was part of the selection committee on tour, and the M.C.C. captain, Douglas Jardine, may have discussed tactics with him on the outward journey. Hammond disapproved of Bodyline bowling, believing it to be dangerous, although he understood some of the reasons for its use.Howat, p. 48. He kept his feelings hidden during the tour, preferring to go along with his captain and the rest of the team. It was not until 1946 that he openly voiced his opinion.

''Wisden'' described Hammond's campaign as successful, although he failed to reach the heights of his previous tour. In the Tests, Hammond scored 440 runs (average 55.00) and took nine wickets (average 32.33), while scoring 948 runs (average 55.76) and taking 20 wickets (average 28.90) in all first-class matches. Although ''Wisden'' said that Hammond accomplished little with the ball, team manager Plum Warner praised his bowling, claiming that during the first Test it was comparable to that of revered former England bowler Sydney Barnes. His best performance was in a match against

''Wisden'' described Hammond's campaign as successful, although he failed to reach the heights of his previous tour. In the Tests, Hammond scored 440 runs (average 55.00) and took nine wickets (average 32.33), while scoring 948 runs (average 55.76) and taking 20 wickets (average 28.90) in all first-class matches. Although ''Wisden'' said that Hammond accomplished little with the ball, team manager Plum Warner praised his bowling, claiming that during the first Test it was comparable to that of revered former England bowler Sydney Barnes. His best performance was in a match against New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

, where he took six for 43, including the wicket of Bradman. In an early game on tour against Victoria, Hammond was instructed by Jardine to attack the bowling of Chuck Fleetwood-Smith

Leslie O'Brien "Chuck" Fleetwood-Smith (30 March 1908 – 16 March 1971) was a cricketer who played for Victoria and Australia. Known universally as "Chuck", he was the "wayward genius" of Australian cricket during the 1930s. A slow bowler wh ...

, who was on the verge of making his Test debut. Hammond scored 203, freely punishing Fleetwood-Smith's bowling and in effect delaying his Test debut for several years.Foot, p. 117.

In England's victory in the first Test, Hammond scored 112, playing powerfully through the off side. He took two wickets in two balls in the second Australian innings, making the ball move around. In the second Test, he bowled spin, as England left out Hedley Verity

Hedley Verity (18 May 1905 – 31 July 1943) was a professional cricketer who played for Yorkshire and England between 1930 and 1939. A slow left-arm orthodox bowler, he took 1,956 wickets in first-class cricket at an average of 14.90 ...

, their specialist spinner; his bowling impressed Jardine and the ''Wisden'' correspondent. His bowling against Bradman, who scored an unbeaten century, produced a personal duel that struck observers as particularly tense. Hammond took three for 23 in the second innings but achieved little with the bat as England lost the match. In the third Test, he appeared uncomfortable facing Tim Wall's fast, short bowling, and was heard to say, "If that's what the bloody game's coming to, I've had enough of it!" He scored 85 in the second innings before being bowled by a full toss

A full toss is a type of delivery in the sport of cricket. It describes any delivery that reaches the batsman without bouncing on the pitch first.

A full toss which reaches the batsman above the waist is called a beamer. This is not a valid ...

from Bradman, to his annoyance. Hammond did not pass 20 runs in England's Ashes-securing victory in the fourth Test, attracting criticism from ''Wisden'' and others for overcautious batting. He returned to form in the final Test at Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mounta ...

, a ground on which he was often successful, scoring 101 and 75 not out. ''Wisden'' praised his style and brilliant play, and he ended the match with a six, securing England's third successive victory and a 4–1 series win.

A short tour of New Zealand followed; Hammond scored 621 runs in three first-class innings. In the first Test, he scored 227, and in the second and final Test, he broke the world record for a Test innings on 1 April by scoring 336 not out. His record innings began cautiously, but against a weak bowling side, he increased his scoring rate after making his century and again after reaching 200. As he passed Bradman's record of 334, he shouted "Yes!" He hit ten sixes, then a Test record, including three from consecutive balls. However, the weakness of the bowling compared to that faced by Bradman and the importance of Ashes matches meant that Hammond's record was not as prestigious as the Australian's. When Len Hutton

Sir Leonard Hutton (23 June 1916 – 6 September 1990) was an English cricketer. He played as an opening batsman for Yorkshire County Cricket Club from 1934 to 1955 and for England in 79 Test matches between 1937 and 1955. '' Wisden Cricke ...

broke the record in 1938, he considered Bradman's 334 the score to beat.

Loss of Test form

The Bodyline controversy continued into the 1933 season. Bodyline tactics were used in several matches, including by the West Indian tourists in the second Test.Frith, pp. 355, 361–64. In all first-class cricket, Hammond, no longer vice-captain of Gloucestershire, scored 3,323 runs, passing 3,000 in a season for the first time. With an average of 67.81, he topped the first-class tables for what would be the first of eight successive seasons. He also took 38 wickets. However, his highest score in three Test innings was 34. In the second Test, unsettled by Bodyline, Hammond was cut on the chin by a short ball, causing him to retire hurt. He again commented that he would quit rather than face such bowling; soon after his return, he was out.Les Ames

Leslie Ethelbert George Ames (3 December 1905 – 27 February 1990) was a wicket-keeper and batsman for the England cricket team and Kent County Cricket Club. In his obituary, ''Wisden'' described him as the greatest wicket-keeper-batsman of a ...

, who played in the three-match series, won by England 2–0, believed that the West Indian pacemen worried Hammond, who showed a weakness against short, fast bowling.Foot, p. 129.

Hammond spent much of the 1934 season troubled by sore throats and back problems which restricted his appearances for Gloucestershire. His form for his county was good and in all first-class matches, he scored 2,366 runs (average 76.32), although he took fewer wickets at a higher average than the previous season.Howat, p. 57. Awarded a benefit match, which raised just over £2,600, Hammond was idolised by the press and public for his achievements. In Tests, it was a different story; according to ''Wisden'', he failed badly. England lost the Ashes, 2–1, in a series overshadowed at times by the Bodyline controversy. Hammond played in all five Tests against Australia but his top score was 43; he scored 162 runs at an average of 20.25, and took five wickets at an average of 72.80. Although the press and selectors supported him, there were some suggestions he should be left out of the side, and Hammond felt under great pressure.

The pattern of failure in Test matches but success elsewhere continued during the 1934–35 tour of the West Indies. In all first-class cricket he scored 789 runs, averaging 56.35, with an innings of 281 not out the highest of his three centuries. The four-Test series, which England lost 2–1, was another matter. ''Wisden'' noted that the West Indian pace attack, considered the best in the world by Bob Wyatt, unsettled the English batsmen; the home bowlers were accused of intimidation by some of the England side. Hammond had a top score of 47 and scored 175 runs at an average of 25.00. He played well in difficult batting conditions, which he believed were among the worst he ever faced, in the first Test. In the first innings he scored 43, before dominating the bowlers at a critical time in his unbeaten 29 in the second innings, winning the match with a six.

Hammond's health remained poor at the start of the 1935 season. He developed septic tonsillitis

Tonsillitis is inflammation of the tonsils in the upper part of the throat. It can be acute or chronic. Acute tonsillitis typically has a rapid onset. Symptoms may include sore throat, fever, enlargement of the tonsils, trouble swallowing, a ...

which made it difficult for him to breathe, eat and sleep, and ultimately required an operation to remove his tonsils in early 1936.Howat, p. 65. Hammond's form was indifferent and he believed it was his worst season.Hammond, p. 119. In first-class matches, he scored 2,616 runs (average 49.35) and took 60 wickets (average 27.26). He became the ninth player to reach 100 first-class centuries, emerging from a run of bad form against Somerset. Long a regular in the side, for the first time he captained the Players against the Gentlemen at Lord's. In the five-Test series against South Africa, a run of low scores again brought press speculation about his place in the national side. He did not pass fifty until the third Test, when he scored 63 and 87 not out, ending a run of 22 innings without a fifty, in which time he averaged 23.47 over 14 Tests. Hammond made two more fifties in the last two Tests, although they were insufficient to prevent England from losing 1–0, their third successive series defeat. He finished the series with 389 runs at an average of 64.83, but remained unsatisfied with his form.

Return to form

As the 1936 season began, Hammond remained weak from the recent removal of his tonsils. Returning to cricket too soon, he was in poor form; he took a longer rest, which caused him to miss the first of three Tests against India. It was July before he felt fully well. In all first-class cricket that season, Hammond scored 2,107 runs, averaging 56.94, and took 41 wickets. In county cricket, Gloucestershire appointed a new captain,

As the 1936 season began, Hammond remained weak from the recent removal of his tonsils. Returning to cricket too soon, he was in poor form; he took a longer rest, which caused him to miss the first of three Tests against India. It was July before he felt fully well. In all first-class cricket that season, Hammond scored 2,107 runs, averaging 56.94, and took 41 wickets. In county cricket, Gloucestershire appointed a new captain, Dallas Page

Dallas () is the List of municipalities in Texas, third largest city in Texas and the largest city in the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, the List of metropolitan statistical areas, fourth-largest metropolitan area in the United States at 7.5 ...

. Hammond had been offered the joint captaincy with Bev Lyon, conditional on his becoming assistant secretary at the club to enable him to play as an amateur, but declined for financial reasons. Hammond returned to the England side for the second Test, making 167, his first century in 28 innings, scoring quickly throughout. He was praised by ''Wisden'' for his control. Hammond continued to score heavily in the third Test, making 217 after being dropped twice early on. His highest score came in the last county match of the season, at Gloucestershire, which was Tom Goddard's benefit match. A difficult pitch meant that wickets tumbled on the first day, prompting fears of an early finish which would possibly lose money for Goddard. Hammond batted all of the second day, ensuring the match lasted the full three days, to score 317 out of a total of 485.

Selected for the M.C.C. tour of Australia in 1936–37 under the captaincy of Gubby Allen

Sir George Oswald Browning "Gubby" Allen CBE (31 July 190229 November 1989) was a cricketer who captained England in eleven Test matches. In first-class matches, he played for Middlesex and Cambridge University. A fast bowler and hard-hitti ...

, Hammond was again part of the tour selection committee. He was successful with bat and ball, scoring 1,206 runs (average 67.00) and taking 21 wickets (average 24.57) in all first-class matches in Australia (he played two more in New Zealand at the conclusion of the tour). In Tests, Hammond scored 468 runs at an average of 58.50 and took 12 wickets at an average of 25.08. His tour began with four consecutive first-class hundreds against the state teams, but ''Wisden'' reported that he never recaptured this form during the remainder of the tour, owing to the bowling of Bill O'Reilly. Hammond could not overcome O'Reilly's use of slow leg theory in the later Tests which restricted scoring. England won the first two Tests, although Hammond did not contribute in the first, making a first ball duck

Duck is the common name for numerous species of waterfowl in the family Anatidae. Ducks are generally smaller and shorter-necked than swans and geese, which are members of the same family. Divided among several subfamilies, they are a form ...

. In the second he scored an unbeaten 231, then took three for 29 with the ball in Australia's second innings, during a period when the other bowlers lost control. From this point, his contributions fell away, although he believed that the best innings of his life, on one of the most difficult pitches he ever confronted, was his 32 in the third Test. Neville Cardus, who saw it, described it as remarkable. However, his free-scoring 51 in the second innings was not enough to prevent defeat in the face of an unrealistic target. In the fourth Test, Hammond took five for 57 in Australia's second innings, but his dismissal on the final morning by Fleetwood-Smith ensured that Australia won the match to level the series. One of Hammond's teammates opined that Bradman would not have been dismissed as easily in a similar situation.Cardus, p. 128.Gibson, p. 173. In the decisive final Test, he was restricted by O'Reilly's leg theory attack and failed in the first innings. His 56 in the second innings was not enough to prevent Australia's third win in succession to take the Ashes 3–2.

In the 1937 season, Hammond scored 3,252 runs at an average of 65.04, passing 3,000 runs a second time, and taking 48 wickets. In the three Tests against New Zealand, he passed the previous record number of England appearances, overtaking Frank Woolley's 64 Tests. While scoring 140 in the first Test, he passed the total number of runs scored by Jack Hobbs to become the leading run scorer in Tests, a record he held until it was broken by Colin Cowdrey in December 1970. This innings was his only score above fifty in the series, in which he scored 204 runs (average 51). At the end of the season, in November 1937, it was announced that he had accepted a job, joining the Marsham Tyres board of directors, meaning he would play as an amateur in the future. This led to immediate speculation that he would be made captain of England in the 1938 Ashes series. The chairman of selectors, Plum Warner, later wrote that there was never any doubt from then that Hammond would be captain.

Amateur cricketer

England captain

In the 1938 season, his first as an amateur, Hammond scored 3,011 runs at an average of 75.27. During the season, he was elected to life membership of Gloucestershire and membership of the M.C.C., which barred professionals. He captained the Gentlemen against the Players at Lord's—having previously led the Players, he is the only person to skipper both teams. Early in the season, he led England in a Test trial before, as expected, being given the role full-time against Australia. His leadership during the series, which was drawn 1–1, won him praise.Howat, p. 81. He was criticised, however, for his handling of bowlers, specifically for not giving enough work to spinnersHedley Verity

Hedley Verity (18 May 1905 – 31 July 1943) was a professional cricketer who played for Yorkshire and England between 1930 and 1939. A slow left-arm orthodox bowler, he took 1,956 wickets in first-class cricket at an average of 14.90 ...

in the first Test or Doug Wright in the fourth. In the second Test, he scored 240, briefly a record for an England batsman playing at home, to rescue the side from a poor start. This innings was lauded by observers including Warner, Bradman and Cardus, and ''The Times'' correspondent pronounced it one of the best ever. The match, like the first, was drawn and with the third Test completely washed out by rain, the crucial match proved to be the fourth. In a low-scoring game, Hammond scored 76, holding England's first innings together. In the second innings, however, he made a first-ball duck; an English batting collapse allowed Australia to win the match and retain the Ashes. England had some consolation with a massive victory in the final Test; following Hammond's instructions to be cautious, the side slowly amassed a record total of 903 for seven, with Hutton beating Hammond's Test record innings by scoring 364. Hammond scored 59, giving him 403 runs at an average of 67.16 in the series.

In the 1938–39 season, Hammond captained the M.C.C. tour of South Africa in a five-match series. ''Wisden'' criticised both sides for slow play, and the almanack's correspondent felt Hammond was reluctant to try to force a win. In general, though, judgements on his captaincy were positive; his teammates and opponents believed he had firm control of the side and E. W. Swanton

Ernest William Swanton (11 February 1907 – 22 January 2000) was an English journalist and author, chiefly known for being a cricket writer and commentator under his initials, E. W. Swanton. He worked as a sports journalist for ''The Daily T ...

complimented his tactics. In the Tests, he used the cautious batting method which had been successful in Australia. He scored three Test centuries, making 181 after a shaky start in the second Test, a quick 120 in the third and 140 in the fifth. England won the third match, the only one in the series with a result, and Hammond was praised for his use of bowlers. The final match, in which Hammond lost the toss, having previously won it eight consecutive times, was drawn after ten days' play. In the fourth innings, England faced a victory target of 696. Hammond was credited with nearly forcing a remarkable win, first by promoting Bill Edrich

William John Edrich (26 March 1916 – 24 April 1986) was a first-class cricketer who played for Middlesex, Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC), Norfolk and England.

Edrich's three brothers, Brian, Eric and Geoff, and also his cousin, John, all pla ...

, who had failed thus far in the series but scored 219, and then by playing himself what ''Wisden'' described as "one of the finest innings of his career" before rain forced the match to be abandoned. Hammond also tallied two fifties in the series to score 609 runs in total, at an average of 87.00. In all first-class tour matches, he scored 1,025 runs (average 60.29). While on tour, he met Sybil Ness-Harvey, who was to become his second wife.

Appointed as Gloucestershire captain for the 1939 season, Hammond led the team to third in the County Championship and recorded a rare double victory over Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a Historic counties of England, historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other Eng ...

. While ''Wisden'' commended his adventurous style of leadership, others such as Basil Allen, his predecessor as captain, did not approve; their main criticism was his failure to encourage his players. In first-class cricket, he scored 2,479 runs at an average of 63.56. He placed at the top of the first-class averages for the seventh successive season, although some critics detected a decline in his abilities. While he led England to a 1–0 series victory over West Indies in three Tests, ''Wisden'' reported some criticism of his captaincy. R. C. Robertson-Glasgow

Raymond Charles "Crusoe" Robertson-Glasgow (15 July 1901 – 4 March 1965) was a Scottish cricketer and cricket writer.

Life and career

Robertson-Glasgow was born in Edinburgh and educated at Charterhouse School and Corpus Christi College, Ox ...

said that "Hammond does not rank among the more imaginative England captains", although he concluded by defending Hammond as "experienced and sound". In the second match, he took his 100th catch in Tests, and in the third, he scored 138, his final Test century. In the series, Hammond scored 279 runs (average 55.80). The impending war overshadowed much of the season; throughout the Tests, Hammond made public appeals for citizens to join the armed forces. On the outbreak of the Second World War, he joined the services and was commissioned as a pilot officer in the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve

The Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve (RAFVR) was established in 1936 to support the preparedness of the U.K. Royal Air Force in the event of another war. The Air Ministry intended it to form a supplement to the Royal Auxiliary Air Force (RAuxAF ...

(RAFVR) in October 1939.Howat, p. 93.

Career in the war

Hammond was posted to a training wing of theRoyal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

(RAF) at Hastings in Sussex before he moved with his unit to Torquay

Torquay ( ) is a seaside town in Devon, England, part of the unitary authority area of Torbay. It lies south of the county town of Exeter and east-north-east of Plymouth, on the north of Tor Bay, adjoining the neighbouring town of Paig ...

. He had mainly administrative duties, including instructing recruits, for whom he made life hard. He played some games of cricket in 1940 for various teams before being posted to Cairo in December. His responsibilities in Egypt included organising, promoting and playing in cricket matches. Posted there until 1943, he was promoted to flight lieutenant

Flight lieutenant is a junior Officer (armed forces)#Commissioned officers, commissioned rank in air forces that use the Royal Air Force (RAF) RAF officer ranks, system of ranks, especially in Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth countries. I ...

and then to squadron leader

Squadron leader (Sqn Ldr in the RAF ; SQNLDR in the RAAF and RNZAF; formerly sometimes S/L in all services) is a commissioned rank in the Royal Air Force and the air forces of many countries which have historical British influence. It is als ...

.Foot, pp. 204–5. While Hammond may have helped to raise morale, Cairo was an easy posting during the war and he was not involved directly in combat. He also spent much time in South Africa, where he played cricket and was reunited with Sybil Ness-Harvey. At the beginning of 1944, Hammond was posted back to England, where he lectured and drilled cadets. Playing as captain in many one-day cricket matches, he was praised by ''Wisden'' for encouraging exciting contests. Others applauded his batting, including his hitting of many sixes, fitting the games' relaxed atmosphere. In December 1944, Hammond, suffering from fibrositis

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a medical condition defined by the presence of chronic widespread pain, fatigue, waking unrefreshed, cognitive symptoms, lower abdominal pain or cramps, and depression. Other symptoms include insomnia and a general hype ...

, was discharged from the RAFVR on health grounds and returned to work at Marsham Tyres. Once the war ended in Europe in May 1945, several first-class matches were organised. Hammond played in six, scoring 592 runs at an average of 59.20 with two centuries. In a match for an England team against the Dominions at Lord's, he made a century in each innings, becoming the first man to do this seven times.

End of career

During 1946, the first full season after the war, Hammond played only 26 innings but scored 1,783 runs at an average of 84.90, topping the first-class averages for the eighth time in succession—still an English record as of 2015.Foot, p. 273. At times, he began to show technical weaknesses. Captaining England to a 1–0 victory in a three-Test series against India, he scored one fifty, making 119 runs at an average of 39.66. He batted fifth in the order in the final match, as he would in four of his five remaining Tests. Gloucestershire fell to fifth in the County Championship, and Hammond, after enthusiastically making the team very competitive at the start of the season, became increasingly affected by pain, particularly in damp weather. As captain, he could be irritable and consciously created remoteness and division.Foot, pp. 209–10. Remaining captain of England, Hammond led the M.C.C. side which toured Australia in 1946–47. The visit was unsuccessful as England lost the five-match Test series 3–0. According to ''Wisden'', Hammond's inability to make large scores was one of the reasons for the failure. Nor was he a success as captain. He was criticised for his field placement and people at home wondered if he had lost control of the team. While he suffered some ill luck, ''Wisden'' said that he "was not the same inspiring leader as at home against Australia in 1938". Other journalists noted that he did not consult his players, one of whom later commented that he showed little imagination in his use of bowlers. Hammond approached the tour as an exercise in goodwill, promising his men an enjoyable time. It was noted that Bradman, the Australian captain, took a more competitive attitude towards the series. Team spirit was good on the outward journey, but Hammond's forthcoming divorce and other domestic concerns caused him to become isolated from the players and increasingly moody.Howat, p. 112. He had poor relations with the press, who were very critical of his captaincy and reporting details of the dissolution of his marriage.Foot, p. 217. As the tour progressed, he lost his dynamism as a leader, gave poor advice to the batsmen and made poor selections for the team. As a batsman, Hammond started the tour well, scoring 208 in an early game, but lost form once the Tests began. One of the turning points of the series was a disputed catch in the first Test. Bradman, who looked in poor form and uncertain to continue his cricket career for much longer, had reached 28 when the English team believed he had edged the ball to Jack Ikin at slip. Bradman, as was his entitlement, waited for the umpire's decision instead of leaving the field. The fielders were certain that he was out, but the umpire said he was not, believing the ball had bounced before it was caught; opinion among other participants and spectators was divided. However, Hammond was extremely angry, saying loudly, either to Bradman or the umpires, "a fine fucking way to start a series". Afterwards, relations between Hammond and Bradman deteriorated and there was a coldness between them. Bradman went on to score 187 and Australia won the match and, ultimately, the series. In that first Test, Hammond played two good innings on a very difficult wicket, but in the series, he did not pass fifty, scoring 168 runs at an average of 21.00 before missing the final Test. In all first-class cricket, he scored 633 runs (average 45.21). He suffered increasing pain from fibrositis throughout the series, and later admitted that he felt close to a breakdown. Hammond played his last Test in New Zealand at the end of the tour, scoring 79 in his final innings. He ended his career with 7,249 Test runs at an average of 58.46. His 22 centuries remained an English record until surpassed byAlastair Cook

Sir Alastair Nathan Cook (born 25 December 1984) is an English cricketer who plays for Essex County Cricket Club, and played for England in all international formats from 2006 to 2018. A former captain of the England Test and One-Day Intern ...

in December 2012.

Hammond decided to retire from all cricket after the tour, not returning for Gloucestershire in 1947. Within 24 hours of his arrival back in England, he married Sybil Ness-Harvey. He played only two more first-class games. He scored an unbeaten 92 for the M.C.C. against Ireland in 1950. To help boost a Gloucestershire membership drive, he joined his former side for a match the following year. Although given an excellent reception by the crowd, his tired appearance and struggle to score seven runs before being dismissed embarrassed many of those present. In all first-class cricket, Hammond scored 50,551 runs at an average of 56.10 with 167 centuries. He remains seventh on the list of highest run scorers in first-class cricket and has the third highest number of centuries, as of 2015.

Style and technique

''Wisden's'' obituary described Hammond as one of the top four batsmen who had ever played, calling him "a most exciting cricketer. ... The instant he walked out of a pavilion, white-spotted blue handkerchief showing from his right pocket, bat tucked underarm, cap at a hint of an angle, he was identifiable as a thoroughbred." Throughout the 1930s, the public and critics regarded Hammond as England's best batsman, succeedingJack Hobbs

Sir John Berry Hobbs (16 December 1882– 21 December 1963), always known as Jack Hobbs, was an English professional cricketer who played for Surrey from 1905 to 1934 and for England in 61 Test matches between 1908 and 1930. Known as "The Mast ...

, and next to Bradman, the best in the world (although George Headley also had a claim). Among English batsmen, only Herbert Sutcliffe

Herbert Sutcliffe (24 November 1894 – 22 January 1978) was an English professional cricketer who represented Yorkshire and England as an opening batsman. Apart from one match in 1945, his first-class career spanned the period between the t ...

, with a higher Test average, was similarly successful. According to Alan Gibson, however, although Sutcliffe was dependable in a crisis, "his batting never gave quite the same sense of majesty and excitement that Hammond's did".Gibson, p. 172. More recently, Hammond was one of the inaugural inductees into the ICC Cricket Hall of Fame

The ICC Cricket Hall of Fame recognises "the achievements of the legends of the game from cricket's long and illustrious history". It was launched by the International Cricket Council (ICC) in Dubai on 2 January 2009, in association with the Fe ...

, launched in January 2009, and was selected by a jury of cricket journalists as a member of England's all-time XI in August 2009.

Balanced and still at the crease, Hammond was known for the power and beauty of his driving

Driving is the controlled operation and movement of a vehicle, including cars, motorcycles, trucks, buses, and bicycles. Permission to drive on public highways is granted based on a set of conditions being met and drivers are required to ...

through the off side, although he could play any shot. A very attacking player early in his career, he later became more defensive, playing more frequently off the back foot and abandoning the hook shot as too risky. He was particularly effective on difficult wickets, scoring runs where others struggled to survive. Many of his contemporaries believed that he was the finest off-side player in the history of cricket.Foot, p. 123. In the words of Patrick Murphy, fellow players considered him "on a different plane—majestic, assured, poised, a devastating amalgam of the physical and mental attributes that make up a great batsman."Murphy, p. 96. County bowlers who played against him considered it an achievement merely to prevent him scoring runs.

However, Australian bowlers such as O'Reilly and Grimmett troubled him by bowling at his leg stump, restricting his scoring as he had fewer effective leg-side shots.Swanton, p. 112.Foot, p. 127. Occasionally, he displayed discomfort against the fastest bowlers. His teammate Charlie Barnett said that he did not relish fast bowling, although he was capable of playing it well in the initial stages of his career. Other colleagues, such as Les Ames, Bob Wyatt and Reg Sinfield, believed that he did not like to face the new ball, and he was occasionally happy for the other batsmen to face the difficult bowling.

His bowling was smooth and effortless, with a classical action. He could bowl fast, but more often bowled at fast-medium pace. He could make the ball swing in humid weather, and deliver off-spin when conditions were suitable. However, Hammond was reluctant to bowl, particularly for Gloucestershire. Bill Bowes

William Eric Bowes (25 July 1908 – 4 September 1987) was an English professional cricketer active from 1929 to 1947 who played in 372 first-class matches as a right arm fast bowler and a right-handed tail end batsman. He took 1,639 wicke ...

believed that he was a very good bowler who would not take it seriously.Foot, p. 131. In his obituary, ''Wisden'' said that "at slip he had no superior. He stood all but motionless, moved late but with uncanny speed, never needing to stretch or strain but plucking the ball from the air like an apple from a tree." He was also able to field further away from the batsmen than was the norm, particularly in his younger days, as he could chase the ball quickly and had a very good throwing arm.

Personal life

Personality

Hammond struck his contemporaries as a sad figure, a loner with few friends in cricket. He rarely encouraged young players or gave out praise. He liked to mix with middle-class people, spending money he did not really have, leading to accusations of snobbery. Teammates regarded him as moody, private and uncommunicative. Often silent in the company of others, he could be arrogant and unfriendly. Charlie Barnett and Charles Dacre, two of his Gloucestershire teammates, came almost to hate him. Dacre often played in a reckless way of which Hammond disapproved; Hammond, in turn, may have been jealous of him. Hammond once tried hard to injure Dacre by bowling fast at him while he was wicketkeeper. Barnett began as a close friend but fell out over Hammond's treatment of his first wife and later his refusal to play in Barnett's benefit match.Foot, pp. 162–64. Other players who were involved in disputes with Hammond included Denis Compton, whose cavalier approach Hammond disliked, and Learie Constantine, who believed Hammond insulted him in the West Indies in 1925, although the two later made peace. Hammond's ultimate rivalry was with Bradman, who overshadowed him throughout his career, and with whom he developed an increasing obsession. It was not enough for Hammond to be the second-best batsman in the world, and he disliked the constant comparisons made between them in Bradman's favour. He felt not only that he had to do well, but also that he had to score more than Bradman.Marriage

David Foot quotes an unnamed cricketer saying that the two ruling passions of Hammond's life "were his cricket bat and his genitals". His strong desire for women was noticed by teammates from early in his career. Foot believes that Hammond had sexual relationships with many women, sometimes several contemporaneously, before and during his first marriage, some of which led to marriage proposals. This was widely known in cricket circles, prompting disapproval from figures such as Barnett.Foot, pp. 6, 13, 162–64, 181–82. In 1929, Hammond married Dorothy Lister, the daughter of a Yorkshire textile merchant, in a highly publicised ceremony at a parish church inBingley

Bingley is a market town and civil parish in the metropolitan borough of the City of Bradford, West Yorkshire, England, on the River Aire and the Leeds and Liverpool Canal, which had a population of 18,294 at the 2011 Census.

Bingley ra ...

. They met at a cricket match in 1927 but spent little time together before the wedding, having little in common. When married, they rarely communicated or got on well. Acquaintances believed Hammond treated her badly, particularly once her father lost nearly everything in the Depression, causing them financial worry. She remained loyal, but their relations gradually broke down, even after she sailed to South Africa, joining Hammond on tour in 1939 in an attempt to save the marriage. By that time, he was already seeing his future second wife, Sybil Ness-Harvey, a former beauty queen whom he had met while on tour.

During the war, Hammond spent much of his leave with Ness-Harvey in South Africa. In 1945, she followed him back to England, but did not like it. When Hammond left to tour Australia in 1946–47, Ness-Harvey remained behind with his mother, with whom she did not get along. This was one of the factors which led to Hammond's problems on the tour. His divorce went through, and on his return, he and Sybil married at Kingston Register Office

A register office or The General Register Office, much more commonly but erroneously registry office (except in official use), is a British government office where births, deaths, marriages, civil partnership, stillbirths and adoptions in Eng ...

. She had already changed her name to Hammond by deed poll

A deed poll (plural: deeds poll) is a legal document binding on a single person or several persons acting jointly to express an intention or create an obligation. It is a deed, and not a contract because it binds only one party.

Etymology

The ...

. Their first child, Roger, was born in 1948. Carolyn was born in 1950Howat, p. 129. and Valerie was born in 1952.

Business