A writer is a person who uses

written words in different

writing style

In literature, writing style is the manner of expressing thought in language characteristic of an individual, period, school, or nation. As Bryan Ray notes, however, style is a broader concern, one that can describe "readers' relationships with, t ...

s and techniques to communicate ideas. Writers produce different forms of literary art and creative writing such as

novel

A novel is a relatively long work of narrative fiction, typically written in prose and published as a book. The present English word for a long work of prose fiction derives from the for "new", "news", or "short story of something new", itsel ...

s,

short stories

A short story is a piece of prose fiction that typically can be read in one sitting and focuses on a self-contained incident or series of linked incidents, with the intent of evoking a single effect or mood. The short story is one of the oldest ...

,

book

A book is a medium for recording information in the form of writing or images, typically composed of many pages (made of papyrus, parchment, vellum, or paper) bound together and protected by a cover. The technical term for this phys ...

s,

poetry

Poetry (derived from the Greek '' poiesis'', "making"), also called verse, is a form of literature that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language ŌłÆ such as phonaesthetics, sound symbolism, and metre ŌłÆ to evoke meanings ...

,

travelogues,

plays,

screenplay

''ScreenPlay'' is a television drama anthology series broadcast on BBC2 between 9 July 1986 and 27 October 1993.

Background

After single-play anthology series went off the air, the BBC introduced several showcases for made-for-television, ...

s,

teleplay

A teleplay is a screenplay or script used in the production of a scripted television program or series. In general usage, the term is most commonly seen in reference to a standalone production, such as a television film, a television play, or a ...

s,

song

A song is a musical composition intended to be performed by the human voice. This is often done at distinct and fixed pitches (melodies) using patterns of sound and silence. Songs contain various forms, such as those including the repetiti ...

s, and

essay

An essay is, generally, a piece of writing that gives the author's own argument, but the definition is vague, overlapping with those of a letter, a paper, an article, a pamphlet, and a short story. Essays have been sub-classified as formal ...

s as well as other

report

A report is a document that presents information in an organized format for a specific audience and purpose. Although summaries of reports may be delivered orally, complete reports are almost always in the form of written documents. Usage

In ...

s and

news articles

An article or piece is a written work published in a print or electronic medium. It may be for the purpose of propagating news, research results, academic analysis, or debate.

News articles

A news article discusses current or recent news of ei ...

that may be of interest to the

general public. Writers' texts are published across a wide range of

media

Media may refer to:

Communication

* Media (communication), tools used to deliver information or data

** Advertising media, various media, content, buying and placement for advertising

** Broadcast media, communications delivered over mass el ...

. Skilled writers who are able to use

language

Language is a structured system of communication. The structure of a language is its grammar and the free components are its vocabulary. Languages are the primary means by which humans communicate, and may be conveyed through a variety of ...

to express

idea

In common usage and in philosophy, ideas are the results of thought. Also in philosophy, ideas can also be mental representational images of some object. Many philosophers have considered ideas to be a fundamental ontological category of be ...

s well, often contribute significantly to the

cultural content of a society.

The term "writer" is also used elsewhere in the arts and music, such as songwriter or a screenwriter, but also a stand-alone "writer" typically refers to the creation of written language. Some writers work from an

oral tradition

Oral tradition, or oral lore, is a form of human communication wherein knowledge, art, ideas and cultural material is received, preserved, and transmitted orally from one generation to another. Vansina, Jan: ''Oral Tradition as History'' (1985 ...

.

Writers can produce material across a number of genres,

fictional or

non-fictional

Nonfiction, or non-fiction, is any document or media content that attempts, in good faith, to provide information (and sometimes opinions) grounded only in facts and real life, rather than in imagination. Nonfiction is often associated with be ...

. Other writers use multiple media such as graphics or illustration to enhance the communication of their ideas. Another recent demand has been created by civil and government readers for the work of non-fictional technical writers, whose skills create understandable, interpretive documents of a practical or scientific kind. Some writers may use

image

An image is a visual representation of something. It can be two-dimensional, three-dimensional, or somehow otherwise feed into the visual system to convey information. An image can be an artifact, such as a photograph or other two-dimensio ...

s (drawing, painting, graphics) or

multimedia

Multimedia is a form of communication that uses a combination of different content forms such as text, audio, images, animations, or video into a single interactive presentation, in contrast to tradi ...

to augment their writing. In rare instances, creative writers are able to communicate their ideas via music as well as words.

As well as producing their own written works, writers often write about ''how'' they write (their

writing process);

''why'' they write (that is, their motivation);

[See, for example, ] and also comment on the work of other writers (criticism). Writers work professionally or non-professionally, that is, for payment or without payment and may be paid either in advance, or on acceptance, or only after their work is published. Payment is only one of the motivations of writers and many are not paid for their work.

The term ''writer'' has been used as a synonym of ''author'', although the latter term has a somewhat broader meaning and is used to convey legal responsibility for a piece of writing, even if its

composition is anonymous, unknown or collaborative. Author most often refers to the writer of a book.

Types

Writers choose from a range of

literary genre

A literary genre is a category of literature. Genres may be determined by literary technique, tone, content, or length (especially for fiction). They generally move from more abstract, encompassing classes, which are then further sub-divided ...

s to express their ideas. Most writing can be adapted for use in another medium. For example, a writer's work may be read privately or recited or performed in a play or film. Satire for example, may be written as a poem, an essay, a film, a comic play, or a part of journalism. The writer of a letter may include elements of criticism, biography, or journalism.

Many writers work across genres. The genre sets the parameters but all kinds of creative adaptation have been attempted: novel to film; poem to play; history to musical. Writers may begin their career in one genre and change to another. For example, historian

William Dalrymple began in the genre of

travel literature

The genre of travel literature encompasses outdoor literature, guide books, nature writing, and travel memoirs.

One early travel memoirist in Western literature was Pausanias, a Greek geographer of the 2nd century CE. In the early modern pe ...

and also writes as a journalist. Many writers have produced both fiction and non-fiction works and others write in a genre that crosses the two. For example, writers of

historical romance

Historical romance is a broad category of mass-market fiction focusing on romantic relationships in historical periods, which Walter Scott helped popularize in the early 19th century.

Varieties Viking

These books feature Vikings during the D ...

s, such as

Georgette Heyer

Georgette Heyer (; 16 August 1902 ŌĆō 4 July 1974) was an English novelist and short-story writer, in both the Regency romance and detective fiction genres. Her writing career began in 1921, when she turned a story for her younger brothe ...

, create characters and stories set in historical periods. In this genre, the accuracy of the history and the level of factual detail in the work both tend to be debated. Some writers write both creative fiction and serious analysis, sometimes using other names to separate their work.

Dorothy Sayers

Dorothy Leigh Sayers (; 13 June 1893 ŌĆō 17 December 1957) was an English crime writer and poet. She was also a student of classical and modern languages.

She is best known for her mysteries, a series of novels and short stories set between th ...

, for example, wrote crime fiction but was also a playwright, essayist, translator, and critic.

Literary and creative

Poet

Poets make maximum use of the language to achieve an emotional and sensory effect as well as a cognitive one. To create these effects, they use

rhyme

A rhyme is a repetition of similar sounds (usually, the exact same phonemes) in the final stressed syllables and any following syllables of two or more words. Most often, this kind of perfect rhyming is consciously used for a musical or aesthetic ...

and rhythm and they also apply the properties of words with a range of other techniques such as

alliteration

Alliteration is the conspicuous repetition of initial consonant sounds of nearby words in a phrase, often used as a literary device. A familiar example is "Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers". Alliteration is used poetically in various ...

and

assonance

Assonance is a resemblance in the sounds of words/syllables either between their vowels (e.g., ''meat, bean'') or between their consonants (e.g., ''keep, cape''). However, assonance between consonants is generally called ''consonance'' in America ...

. A common topic is love and its vicissitudes.

Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 ŌĆō 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

's best-known love story ''

Romeo and Juliet

''Romeo and Juliet'' is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare early in his career about the romance between two Italian youths from feuding families. It was among Shakespeare's most popular plays during his lifetime and, along with ''Ham ...

'', for example, written in a variety of poetic forms, has been performed in innumerable theaters and made into at least eight cinematic versions.

John Donne

John Donne ( ; 22 January 1572 ŌĆō 31 March 1631) was an English poet, scholar, soldier and secretary born into a recusant family, who later became a cleric in the Church of England. Under royal patronage, he was made Dean of St Paul's Cathedr ...

is another poet renowned for his love poetry.

Novelist

Satirist

A satirist uses wit to ridicule the shortcomings of society or individuals, with the intent of revealing stupidity. Usually, the subject of the satire is a contemporary issue such as ineffective political decisions or politicians, although human vices such as

greed

Greed (or avarice) is an uncontrolled longing for increase in the acquisition or use of material gain (be it food, money, land, or animate/inanimate possessions); or social value, such as status, or power. Greed has been identified as undes ...

are also a common and prevalent subject. Philosopher

Voltaire

Fran├¦ois-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his '' nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his criticism of ChristianityŌĆöes ...

wrote a satire about optimism called ''

Candide

( , ) is a French satire written by Voltaire, a philosopher of the Age of Enlightenment, first published in 1759. The novella has been widely translated, with English versions titled ''Candide: or, All for the Best'' (1759); ''Candide: or, Th ...

'', which was subsequently turned into an opera, and many well known lyricists wrote for it. There are elements of

Absurdism

Absurdism is the philosophical theory that existence in general is absurd. This implies that the world lacks meaning or a higher purpose and is not fully intelligible by reason. The term "absurd" also has a more specific sense in the context o ...

in ''Candide'', just as there are in the work of contemporary satirist

Barry Humphries, who writes comic satire for his character

Dame Edna Everage to perform on stage.

Satirists use different techniques such as

irony,

sarcasm

Sarcasm is the caustic use of words, often in a humorous way, to mock someone or something. Sarcasm may employ ambivalence, although it is not necessarily ironic. Most noticeable in spoken word, sarcasm is mainly distinguished by the inflection ...

, and

hyperbole

Hyperbole (; adj. hyperbolic ) is the use of exaggeration as a rhetorical device or figure of speech. In rhetoric, it is also sometimes known as auxesis (literally 'growth'). In poetry and oratory, it emphasizes, evokes strong feelings, and c ...

to make their point and they choose from the full range of genres ŌĆō the satire may be in the form of prose or poetry or dialogue in a film, for example. One of the most well-known satirists is

Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667 ŌĆō 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish satirist, author, essayist, political pamphleteer (first for the Whigs, then for the Tories), poet, and Anglican cleric who became Dean of St Patrick's Cathedral, ...

who wrote the four-volume work ''

Gulliver's Travels

''Gulliver's Travels'', or ''Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World. In Four Parts. By Lemuel Gulliver, First a Surgeon, and then a Captain of Several Ships'' is a 1726 prose satire by the Anglo-Irish writer and clergyman Jonathan ...

'' and many other satires, including ''

A Modest Proposal'' and ''

The Battle of the Books''.

Short story writer

A short story writer is a writer of short stories, works of fiction that can be read in a single sitting.

Performative

Librettist

Libretti (the plural of libretto) are the texts for musical works such as operas. The Venetian poet and librettist

Lorenzo Da Ponte, for example, wrote the libretto for some of

Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 17565 December 1791), baptised as Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart, was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period. Despite his short life, his rapid pace of composition r ...

's greatest operas.

Luigi Illica and

Giuseppe Giacosa were Italian librettists who wrote for

Giacomo Puccini

Giacomo Puccini (Lucca, 22 December 1858Bruxelles, 29 November 1924) was an Italian composer known primarily for his operas. Regarded as the greatest and most successful proponent of Italian opera after Verdi, he was descended from a long l ...

. Most opera composers collaborate with a librettist but unusually,

Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most o ...

wrote both the music and the libretti for his works himself.

Lyricist

Usually writing in verses and choruses, a lyricist specializes in writing

lyrics

Lyrics are words that make up a song, usually consisting of verses and choruses. The writer of lyrics is a lyricist. The words to an extended musical composition such as an opera are, however, usually known as a "libretto" and their writer ...

, the words that accompany or underscore a song or opera. Lyricists also write the words for songs. In the case of

Tom Lehrer

Thomas Andrew Lehrer (; born April 9, 1928) is an American former musician, singer-songwriter, satirist, and mathematician, having lectured on mathematics and musical theater. He is best known for the pithy and humorous songs that he recorded i ...

, these were satirical. Lyricist

Noël Coward

Sir Noël Peirce Coward (16 December 189926 March 1973) was an English playwright, composer, director, actor, and singer, known for his wit, flamboyance, and what ''Time (magazine), Time'' magazine called "a sense of personal style, a combina ...

, who wrote musicals and songs such as "

Mad Dogs and Englishmen" and the recited song "

I Went to a Marvellous Party", also wrote plays and films and performed on stage and screen as well. Writers of lyrics, such as these two, adapt other writers' work as well as create entirely original parts.

Playwright

A playwright writes plays which may or may not be performed on a stage by actors. A play's narrative is driven by dialogue. Like novelists, playwrights usually explore a theme by showing how people respond to a set of circumstances. As writers, playwrights must make the language and the dialogue succeed in terms of the characters who speak the lines as well as in the play as a whole. Since most plays are performed, rather than read privately, the playwright has to produce a text that works in spoken form and can also hold an audience's attention over the period of the performance. Plays tell "a story the audience should care about", so writers have to cut anything that worked against that.

Plays may be written in prose or verse. Shakespeare wrote plays in

iambic pentameter

Iambic pentameter () is a type of metric line used in traditional English poetry and verse drama. The term describes the rhythm, or meter, established by the words in that line; rhythm is measured in small groups of syllables called " feet". "Ia ...

as does

Mike Bartlett in his play ''King Charles III'' (2014).

Playwrights also adapt or re-write other works, such as plays written earlier or literary works originally in another genre. Famous playwrights such as

Henrik Ibsen

Henrik Johan Ibsen (; ; 20 March 1828 ŌĆō 23 May 1906) was a Norwegian playwright and theatre director. As one of the founders of modernism in theatre, Ibsen is often referred to as "the father of realism" and one of the most influential pla ...

or

Anton Chekhov

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov (; 29 January 1860Old Style date 17 January. ŌĆō 15 July 1904Old Style date 2 July.) was a Russian playwright and short-story writer who is considered to be one of the greatest writers of all time. His career a ...

have had their works adapted several times. The plays of early Greek playwrights

Sophocles

Sophocles (; grc, ╬Ż╬┐Žå╬┐╬║╬╗ß┐åŽé, , Sophoklß╗ģs; 497/6 ŌĆō winter 406/5 BC)Sommerstein (2002), p. 41. is one of three ancient Greek tragedians, at least one of whose plays has survived in full. His first plays were written later than, or c ...

,

Euripides

Euripides (; grc, ╬ĢßĮÉŽü╬╣ŽĆ╬»╬┤╬ĘŽé, Eur─½p├Łd─ōs, ; ) was a tragedian of classical Athens. Along with Aeschylus and Sophocles, he is one of the three ancient Greek tragedians for whom any plays have survived in full. Some ancient scholars ...

, and

Aeschylus

Aeschylus (, ; grc-gre, ╬æß╝░ŽāŽćŽŹ╬╗╬┐Žé ; c. 525/524 ŌĆō c. 456/455 BC) was an ancient Greek tragedian, and is often described as the father of tragedy. Academic knowledge of the genre begins with his work, and understanding of earlier Gree ...

are still performed. Adaptations of a playwright's work may be honest to the original or creatively interpreted. If the writers' purpose in re-writing the play is to make a film, they will have to prepare a screenplay. Shakespeare's plays, for example, while still regularly performed in the original form, are often adapted and abridged, especially for the

cinema. An example of a creative modern adaptation of a play that nonetheless used the original writer's words, is

Baz Luhrmann

Mark Anthony Luhrmann (born 17 September 1962), known professionally as Baz Luhrmann, is an Australian film director, producer, writer and actor. With projects spanning film, television, opera, theatre, music and recording industries, he is re ...

's version of ''

Romeo and Juliet

''Romeo and Juliet'' is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare early in his career about the romance between two Italian youths from feuding families. It was among Shakespeare's most popular plays during his lifetime and, along with ''Ham ...

''. The amendment of the name to ''

Romeo + Juliet

Romeo Montague () is the male protagonist of William Shakespeare's tragedy ''Romeo and Juliet''. The son of Lord Montague and his wife, Lady Montague, he secretly loves and marries Juliet, a member of the rival House of Capulet, through a pries ...

'' indicates to the audience that the version will be different from the original.

Tom Stoppard

Sir Tom Stoppard (born , 3 July 1937) is a Czech born British playwright and screenwriter. He has written for film, radio, stage, and television, finding prominence with plays. His work covers the themes of human rights, censorship, and politi ...

's play ''

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead

''Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead'' is an absurdist, existential tragicomedy by Tom Stoppard, first staged at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe in 1966. The play expands upon the exploits of two minor characters from Shakespeare's ''Haml ...

'' is a play inspired by Shakespeare's ''

Hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play, with 29,551 words. Set in Denmark, the play depi ...

'' that takes two of Shakespeare's most minor characters and creates a new play in which they are the protagonists.

Screenwriter

Screenwriters write a screenplay ŌĆō or script ŌĆō that provides the words for media productions such as films, television series and video games. Screenwriters may start their careers by writing the screenplay

speculatively; that is, they write a script with no advance payment, solicitation or contract. On the other hand, they may be employed or commissioned to adapt the work of a playwright or novelist or other writer. Self-employed writers who are paid by contract to write are known as

freelancers and screenwriters often work under this type of arrangement.

Screenwriters, playwrights and other writers are inspired by the classic

themes and often use similar and familiar plot devices to explore them. For example, in Shakespeare's ''

Hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play, with 29,551 words. Set in Denmark, the play depi ...

'' is a "play within a play", which the hero uses to demonstrate the king's guilt. Hamlet hives the co-operation of the actors to set up the play as a thing "wherein I'll catch the conscience of the king".

Teleplay

A teleplay is a screenplay or script used in the production of a scripted television program or series. In general usage, the term is most commonly seen in reference to a standalone production, such as a television film, a television play, or a ...

writer

Joe Menosky deploys the same "play within a play" device in an episode of the science fiction

television series

A television show ŌĆō or simply TV show ŌĆō is any content produced for viewing on a television set which can be broadcast via over-the-air, satellite, or cable, excluding breaking news, advertisements, or trailers that are typically placed ...

''

Star Trek: Voyager''. The bronze-age playwright/hero enlists the support of a ''Star Trek'' crew member to create a play that will convince the ruler (or "patron" as he is called), of the futility of war.

Speechwriter

A speechwriter prepares the text for a

speech

Speech is a human vocal communication using language. Each language uses phonetic combinations of vowel and consonant sounds that form the sound of its words (that is, all English words sound different from all French words, even if they are th ...

to be given before a group or crowd on a specific occasion and for a specific purpose. They are often intended to be persuasive or inspiring, such as the speeches given by skilled orators like

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC ŌĆō 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the est ...

; charismatic or influential political leaders like

Nelson Mandela

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela (; ; 18 July 1918 ŌĆō 5 December 2013) was a South African anti-apartheid activist who served as the first president of South Africa from 1994 to 1999. He was the country's first black head of state and the ...

; or for use in a court of law or parliament. The writer of the speech may be the person intended to deliver it, or it might be prepared by a person hired for the task on behalf of someone else. Such is the case when speechwriters are employed by many senior-level elected officials and executives in both government and private sectors.

Interpretive and academic

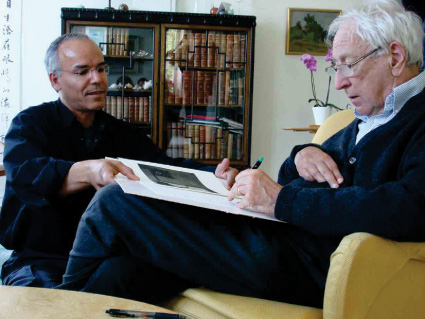

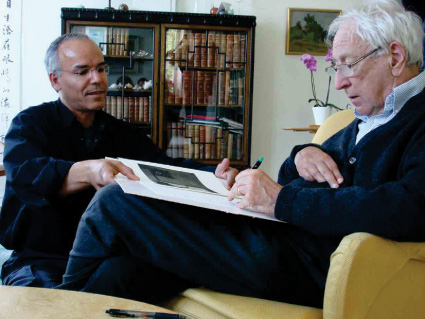

Biographer

Biographers write an account of another person's life.

Richard Ellmann

Richard David Ellmann, FBA (March 15, 1918 ŌĆō May 13, 1987) was an American literary critic and biographer of the Irish writers James Joyce, Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 185430 November 1900) was an Iris ...

(1918ŌĆō1987), for example, was an eminent and award-winning biographer whose work focused on the Irish writers

James Joyce

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce (2 February 1882 ŌĆō 13 January 1941) was an Irish novelist, poet, and literary critic. He contributed to the Modernism, modernist avant-garde movement and is regarded as one of the most influential and important ...

,

William Butler Yeats

William Butler Yeats (13 June 186528 January 1939) was an Irish poet, dramatist, writer and one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. He was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival and became a pillar of the Irish liter ...

, and

Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 185430 November 1900) was an Irish poet and playwright. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular playwrights in London in the early 1890s. He is ...

. For the Wilde biography, he won the 1989

Pulitzer Prize for Biography.

Critic

Critics consider and assess the extent to which a work succeeds in its purpose. The work under consideration may be literary, theatrical, musical, artistic, or architectural. In assessing the success of a work, the critic takes account of why it was done ŌĆō for example, why a text was written, for whom, in what style, and under what circumstances. After making such an assessment, critics write and publish their evaluation, adding the value of their scholarship and thinking to substantiate any opinion. The theory of criticism is an area of study in itself: a good critic understands and is able to incorporate the theory behind the work they are evaluating into their assessment.

[For example, see ] Some critics are already writers in another genre. For example, they might be novelists or essayists. Influential and respected writer/critics include the art critic

Charles Baudelaire

Charles Pierre Baudelaire (, ; ; 9 April 1821 ŌĆō 31 August 1867) was a French poet who also produced notable work as an essayist and art critic. His poems exhibit mastery in the handling of rhyme and rhythm, contain an exoticism inherited ...

(1821ŌĆō1867) and the literary critic

James Wood (born 1965), both of whom have books published containing collections of their criticism. Some critics are poor writers and produce only superficial or unsubstantiated work. Hence, while anyone can be an uninformed critic, the notable characteristics of a good critic are understanding, insight, and an ability to write well.

Editor

An editor prepares literary material for publication. The material may be the editor's own original work but more commonly, an editor works with the material of one or more other people. There are different types of editor.

Copy editors format text to a particular style and/or correct errors in grammar and spelling without changing the text substantively. On the other hand, an editor may suggest or undertake significant changes to a text to improve its readability, sense or structure. This latter type of editor can go so far as to excise some parts of the text, add new parts, or restructure the whole. The work of editors of ancient texts or

manuscript

A manuscript (abbreviated MS for singular and MSS for plural) was, traditionally, any document written by hand ŌĆō or, once practical typewriters became available, typewritten ŌĆō as opposed to mechanically printed or reproduced ...

s or collections of works results in differing editions. For example, there are many editions of

Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 ŌĆō 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

's plays by notable editors who also contribute original introductions to the resulting publication. Editors who work on journals and newspapers have varying levels of responsibility for the text. They may write original material, in particular editorials, select what is to be included from a range of items on offer, format the material, and/or fact check its accuracy.

Encyclopaedist

Encyclopaedists create organised bodies of knowledge.

Denis Diderot

Denis Diderot (; ; 5 October 171331 July 1784) was a French philosopher, art critic, and writer, best known for serving as co-founder, chief editor, and contributor to the ''Encyclop├®die'' along with Jean le Rond d'Alembert. He was a promine ...

(1713ŌĆō1784) is renowned for his contributions to the ''

Encyclop├®die

''Encyclop├®die, ou dictionnaire raisonn├® des sciences, des arts et des m├®tiers'' (English: ''Encyclopedia, or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts''), better known as ''Encyclop├®die'', was a general encyclopedia publis ...

''. The encyclopaedist

Bernardino de Sahag├║n

Bernardino de Sahag├║n, OFM (; ŌĆō 5 February 1590) was a Franciscan friar, missionary priest and pioneering ethnographer who participated in the Catholic evangelization of colonial New Spain (now Mexico). Born in Sahag├║n, Spain, in 1499, he ...

(1499ŌĆō1590) was a

Franciscan

, image = FrancescoCoA PioM.svg

, image_size = 200px

, caption = A cross, Christ's arm and Saint Francis's arm, a universal symbol of the Franciscans

, abbreviation = OFM

, predecessor =

, ...

whose ''Historia general de las cosas de Nueva Espa├▒a'' is a vast encyclopedia of

Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area in southern North America and most of Central America. It extends from approximately central Mexico through Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica. W ...

n civilization, commonly referred to as the ''

Florentine Codex

The ''Florentine Codex'' is a 16th-century ethnographic research study in Mesoamerica by the Spanish Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahag├║n. Sahag├║n originally titled it: ''La Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva Espa├▒a'' (in English: ''The ...

'', after the Italian manuscript library which holds the best-preserved copy.

Essayist

Essayists write essays, which are original pieces of writing of moderate length in which the author makes a case in support of an opinion. They are usually in

prose

Prose is a form of written or spoken language that follows the natural flow of speech, uses a language's ordinary grammatical structures, or follows the conventions of formal academic writing. It differs from most traditional poetry, where the f ...

, but some writers have used poetry to present their argument.

Historian

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it.

The purpose of a historian is to employ

historical analysis to create coherent narratives that explain "what happened" and "why or how it happened". Professional historians typically work in colleges and universities, archival centers, government agencies, museums, and as freelance writers and consultants.

Edward Gibbon

Edward Gibbon (; 8 May 173716 January 1794) was an English historian, writer, and member of parliament. His most important work, '' The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire'', published in six volumes between 1776 and 1788, is ...

's six-volume ''

History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

''The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire'' is a six-volume work by the English historian Edward Gibbon. It traces Western civilization (as well as the Islamic and Mongolian conquests) from the height of the Roman Empire to the ...

'' influenced the development of

historiography

Historiography is the study of the methods of historians in developing history as an academic discipline, and by extension is any body of historical work on a particular subject. The historiography of a specific topic covers how historians hav ...

.

Lexicographer

Writers who create dictionaries are called lexicographers. One of the most famous is

Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson (18 September 1709 ŌĆō 13 December 1784), often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer. The ''Oxford D ...

(1709ŌĆō1784), whose ''

Dictionary of the English Language'' was regarded not only as a great personal scholarly achievement but was also a dictionary of such pre-eminence, that would have been referred to by such writers as

Jane Austen.

Researcher/Scholar

Researchers and scholars who write about their discoveries and ideas sometimes have profound effects on society. Scientists and philosophers are good examples because their new ideas can revolutionise the way people think and how they behave. Three of the best known examples of such a revolutionary effect are

Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (; pl, Miko┼éaj Kopernik; gml, Niklas Koppernigk, german: Nikolaus Kopernikus; 19 February 1473 ŌĆō 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic canon, who formulat ...

, who wrote ''

De revolutionibus orbium coelestium

''De revolutionibus orbium coelestium'' (English translation: ''On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres'') is the seminal work on the heliocentric theory of the astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus (1473ŌĆō1543) of the Polish Renaissance. The boo ...

'' (1543);

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 ŌĆō 19 April 1882) was an English natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

, who wrote ''

On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life''),The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by Me ...

'' (1859); and

Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud ( , ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 ŌĆō 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating psychopathology, pathologies explained as originatin ...

, who wrote ''

The Interpretation of Dreams

''The Interpretation of Dreams'' (german: Die Traumdeutung) is an 1899 book by Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, in which the author introduces his theory of the unconscious with respect to dream interpretation, and discusses what ...

'' (1899).

These three highly influential, and initially very controversial, works changed the way people understood their place in the world. Copernicus's

heliocentric

Heliocentrism (also known as the Heliocentric model) is the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around the Sun at the center of the universe. Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed the Earth ...

view of the cosmos displaced humans from their previously accepted place at the center of the universe; Darwin's evolutionary theory placed humans firmly within, as opposed to above, the order of manner; and Freud's ideas about the power of the

unconscious mind

The unconscious mind (or the unconscious) consists of the processes in the mind which occur automatically and are not available to introspection and include thought processes, memories, interests, and motivations.

Even though these processes exist ...

overcame the belief that humans were consciously in control of all their own actions.

Translator

Translators have the task of finding some equivalence in another language to a writer's meaning, intention and style. Translators whose work has had very significant cultural effect include

Al-ßĖżajj─üj ibn Y┼½suf ibn Maß╣Łar, who translated ''

Elements

Element or elements may refer to:

Science

* Chemical element, a pure substance of one type of atom

* Heating element, a device that generates heat by electrical resistance

* Orbital elements, parameters required to identify a specific orbit of ...

'' from

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

into

Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walte ...

and

Jean-Fran├¦ois Champollion

Jean-Fran├¦ois Champollion (), also known as Champollion ''le jeune'' ('the Younger'; 23 December 17904 March 1832), was a French philologist and orientalist, known primarily as the decipherer of Egyptian hieroglyphs and a founding figure in t ...

, who deciphered

Egyptian hieroglyphs

Egyptian hieroglyphs (, ) were the formal writing system used in Ancient Egypt, used for writing the Egyptian language. Hieroglyphs combined logographic, syllabic and alphabetic elements, with some 1,000 distinct characters.There were about 1, ...

with the result that he could publish the first translation of the

Rosetta Stone

The Rosetta Stone is a stele composed of granodiorite inscribed with three versions of a decree issued in Memphis, Egypt, in 196 BC during the Ptolemaic dynasty on behalf of King Ptolemy V Epiphanes. The top and middle texts are in Ancient ...

hieroglyphs in 1822. Difficulties with translation are exacerbated when words or phrases incorporate rhymes, rhythms, or

puns; or when they have connotations in one language that are non-existent in another. For example, the title of ''

Le Grand Meaulnes

''Le Grand Meaulnes'' () is the only novel by French author Alain-Fournier, who was killed in the first month of World War I. The novel, published in 1913, a year before the author's death, is somewhat autobiographical ŌĆō especially the name of t ...

'' by

Alain-Fournier is supposedly untranslatable because "no English adjective will convey all the shades of meaning that can be read into the simple

renchword 'grand' which takes on overtones as the story progresses."

Translators have also become a part of events where political figures who speak different languages meet to look into the relations between countries or solve political conflicts. It is highly critical for the translator to deliver the right information as a drastic impact could be caused if any error occurred.

Reportage

Blogger

Writers of blogs, which have appeared on the

World Wide Web

The World Wide Web (WWW), commonly known as the Web, is an information system enabling documents and other web resources to be accessed over the Internet.

Documents and downloadable media are made available to the network through web se ...

since the 1990s, need no authorisation to be published. The contents of these short opinion pieces or "posts" form a commentary on issues of specific interest to readers who can use the same technology to interact with the author, with an immediacy hitherto impossible. The ability to link to other sites means that some blog writers ŌĆō and their writing ŌĆō may become suddenly and unpredictably popular.

Malala Yousafzai

Malala Yousafzai ( ur, , , pronunciation: ; born 12 July 1997), is a Pakistani female education activist and the 2014 Nobel Peace Prize laureate. Awarded when she was 17, she is the world's youngest Nobel Prize laureate, and the second Pa ...

, a young Pakistani education activist, rose to prominence due to her blog for

BBC.

A blog writer is using the technology to create a message that is in some ways like a newsletter and in other ways, like a personal letter. "The greatest difference between a blog and a photocopied school newsletter, or an annual family letter photocopied and mailed to a hundred friends, is the potential audience and the increased potential for direct communication between audience members".

Thus, as with other forms of letters the writer knows some of the readers, but one of the main differences is that "some of the audience will be random" and "that presumably changes the way we

riterswrite."

It has been argued that blogs owe a debt to Renaissance essayist

Michel de Montaigne, whose ''Essais'' ("attempts"), were published in 1580, because Montaigne "wrote as if he were chatting to his readers: just two friends, whiling away an afternoon in conversation".

Columnist

Columnists write regular parts for newspapers and other periodicals, usually containing a lively and entertaining expression of opinion. Some columnists have had collections of their best work published as a collection in a book so that readers can re-read what would otherwise be no longer available. Columns are quite short pieces of writing so columnists often write in other genres as well. An example is the female columnist

Elizabeth Farrelly, who besides being a columnist, is also an architecture critic and author of books.

Diarist

Writers who record their experiences, thoughts, or emotions in a sequential form over a period of time in a diary are known as diarists. Their writings can provide valuable insights into historical periods, specific events, or individual personalities. Examples include

Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys (; 23 February 1633 ŌĆō 26 May 1703) was an English diarist and naval administrator. He served as administrator of the Royal Navy and Member of Parliament and is most famous for the diary he kept for a decade. Pepys had no marit ...

(1633ŌĆō1703), an English administrator and Member of Parliament, whose detailed private diary provides eyewitness accounts of events during the 17th century, most notably of the

Great Fire of London

The Great Fire of London was a major conflagration that swept through central London from Sunday 2 September to Thursday 6 September 1666, gutting the medieval City of London inside the old Roman city wall, while also extending past th ...

.

Anne Frank

Annelies Marie "Anne" Frank (, ; 12 June 1929 ŌĆō )Research by The Anne Frank House in 2015 revealed that Frank may have died in February 1945 rather than in March, as Dutch authorities had long assumed"New research sheds new light on Anne Fra ...

(1929ŌĆō1945) was a 13-year-old Dutch girl whose diary from 1942 to 1944 records both her experiences as a persecuted Jew in World War II and an adolescent dealing with intra-family relationships.

Journalist

Journalists write reports about current events after investigating them and gathering information. Some journalists write reports about predictable or scheduled events such as social or political meetings. Others are

investigative journalists

Investigative journalism is a form of journalism in which reporters deeply investigate a single topic of interest, such as serious crimes, political corruption, or corporate wrongdoing. An investigative journalist may spend months or years res ...

who need to undertake considerable research and analysis in order to write an explanation or account of something complex that was hitherto unknown or not understood. Often investigative journalists are reporting criminal or corrupt activity which puts them at risk personally and means that what it is likely that attempts may be made to attack or suppress what they write. An example is

Bob Woodward

Robert Upshur Woodward (born March 26, 1943) is an American investigative journalist. He started working for ''The Washington Post'' as a reporter in 1971 and now holds the title of associate editor.

While a young reporter for ''The Washingto ...

, a journalist who investigated and wrote about

criminal activities by the US President.

Memoirist

Writers of memoirs produce accounts from the memories of their own lives, which are considered unusual, important, or scandalous enough to be of interest to general readers. Although meant to be factual, readers are alerted to the likelihood of some inaccuracies or bias towards an idiosyncratic perception by the choice of genre. A memoir, for example, is allowed to have a much more selective set of experiences than an autobiography which is expected to be more complete and make a greater attempt at balance. Well-known memoirists include

Frances Vane, Viscountess Vane

Frances Anne Vane, Viscountess Vane (formerly Hamilton, ''n├®e'' Hawes; c. January 1715 ŌĆō 31 March 1788), was a British memoirist known for her highly public adulterous relationships.

Early life and first marriage

Frances Anne Hawes was ...

, and

Giacomo Casanova

Giacomo Girolamo Casanova (, ; 2 April 1725 ŌĆō 4 June 1798) was an Italian adventurer and author from the Republic of Venice. His autobiography, (''Story of My Life''), is regarded as one of the most authentic sources of information about the c ...

.

Utilitarian

Ghostwriter

Ghostwriters write for, or in the style of, someone else so the credit goes to the person on whose behalf the writing is done.

Letter writer

Writers of letters use a reliable form of transmission of messages between individuals, and surviving sets of letters provide insight into the motivations, cultural contexts, and events in the lives of their writers.

Peter Abelard

Peter Abelard (; french: link=no, Pierre Ab├®lard; la, Petrus Abaelardus or ''Abailardus''; 21 April 1142) was a medieval French scholastic philosopher, leading logician, theologian, poet, composer and musician. This source has a detailed descr ...

(1079ŌĆō1142), philosopher, logician, and theologian is known not only for the heresy contained in some of his work, and the punishment of having to burn his own book, but also for the letters he wrote to

H├®lo├»se d'Argenteuil .

The letters (or

epistles) of

Paul the Apostle were so influential that over the two thousand years of Christian history, Paul became "second only to Jesus in influence and the amount of discussion and interpretation generated".

Report writer

Report writers are people who gather information, organise and document it so that it can be presented to some person or authority in a position to use it as the basis of a decision. Well-written reports influence policies as well as decisions. For example,

Florence Nightingale

Florence Nightingale (; 12 May 1820 ŌĆō 13 August 1910) was an English social reformer, statistician and the founder of modern nursing. Nightingale came to prominence while serving as a manager and trainer of nurses during the Crimean War, i ...

(1820ŌĆō1910) wrote reports that were intended to effect administrative reform in matters concerning health in the army. She documented her experience in the

Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included t ...

and showed her determination to see improvements: "...after six months of incredible industry she had put together and written with her own hand her ''Notes affecting the Health, Efficiency and Hospital Administration of the British Army.'' This extraordinary composition, filling more than eight hundred closely printed pages, laying down vast principles of far-reaching reform, discussing the minutest detail of a multitude of controversial subjects, containing an enormous mass of information of the most varied kinds ŌĆō military, statistical, sanitary, architectural" became for a long time, the "leading authority on the medical administration of armies".

The logs and reports of

Master mariner William Bligh

Vice-Admiral William Bligh (9 September 1754 ŌĆō 7 December 1817) was an officer of the Royal Navy and a colonial administrator. The mutiny on the HMS ''Bounty'' occurred in 1789 when the ship was under his command; after being set adrift i ...

contributed to his being honourably acquitted at the

court-martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of mem ...

inquiring into the loss of .

Scribe

A scribe writes ideas and information on behalf of another, sometimes copying from another document, sometimes from oral instruction on behalf of an illiterate person, sometimes transcribing from another medium such as a

tape recording

An audio tape recorder, also known as a tape deck, tape player or tape machine or simply a tape recorder, is a sound recording and reproduction device that records and plays back sounds usually using magnetic tape for storage. In its present- ...

,

shorthand

Shorthand is an abbreviated symbolic writing method that increases speed and brevity of writing as compared to longhand, a more common method of writing a language. The process of writing in shorthand is called stenography, from the Greek ''st ...

, or personal notes.

Being able to write was a rare achievement for over 500 years in Western Europe so monks who copied texts were scribes responsible for saving many texts from first times. The monasteries, where monks who knew how to read and write lived, provided an environment stable enough for writing. Irish monks, for example, came to Europe in about 600 and "found manuscripts in places like

Tours

Tours ( , ) is one of the largest cities in the region of Centre-Val de Loire, France. It is the prefecture of the department of Indre-et-Loire. The commune of Tours had 136,463 inhabitants as of 2018 while the population of the whole metr ...

and

Toulouse

Toulouse ( , ; oc, Tolosa ) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, French department of Haute-Garonne and of the larger Regions of France, region of Occitania (administrative region), Occitania. The city is on t ...

" which they copied.

The monastic writers also illustrated their books with highly skilled art work using gold and rare colors.

Technical writer

A technical writer prepares instructions or manuals, such as

user guide

A user guide, also commonly known as a user manual, is intended to assist users in using a particular product, service or application. It's usually written by a technician, product developer, or a company's customer service staff.

Most user guid ...

s or

owner's manuals for users of equipment to follow. Technical writers also write different procedures for business, professional or domestic use. Since the purpose of technical writing is practical rather than creative, its most important quality is clarity. The technical writer, unlike the creative writer, is required to adhere to the relevant

style guide.

Process and methods

Writing process

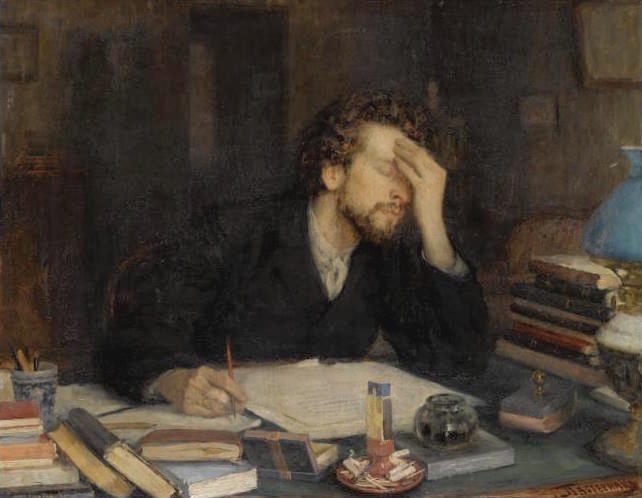

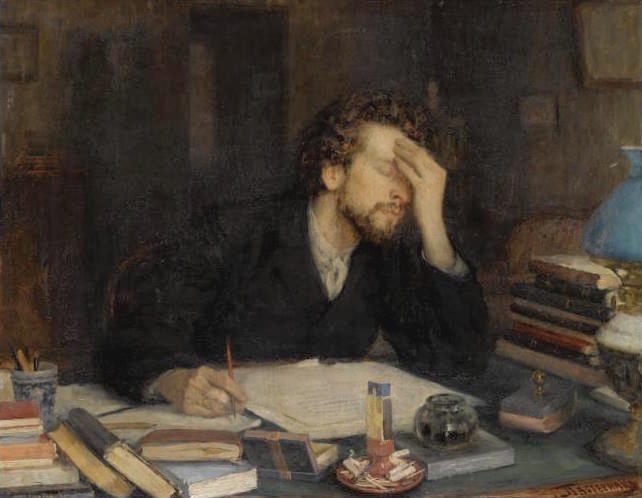

There is a range of approaches that writers take to the task of writing. Each writer needs to find their own process and most describe it as more or less a struggle.

Sometimes writers have had the bad fortune to lose their work and have had to start again. Before the invention of

photocopier

A photocopier (also called copier or copy machine, and formerly Xerox machine, the generic trademark) is a machine that makes copies of documents and other visual images onto paper or plastic film quickly and cheaply. Most modern photocopiers u ...

s and electronic text storage, a writer's work had to be stored on paper, which meant it was very susceptible to fire in particular. (In very earlier times, writers used

vellum

Vellum is prepared animal skin or membrane, typically used as writing material. Parchment is another term for this material, from which vellum is sometimes distinguished, when it is made from calfskin, as opposed to that made from other ani ...

and clay which were more robust materials.) Writers whose work was destroyed before completion include

L. L. Zamenhof

L. L. Zamenhof (15 December 185914 April 1917) was an ophthalmologist who lived for most of his life in Warsaw. He is best known as the creator of Esperanto, the most widely used constructed international auxiliary language.

Zamenhof first dev ...

, the inventor of

Esperanto

Esperanto ( or ) is the world's most widely spoken constructed international auxiliary language. Created by the Warsaw-based ophthalmologist L. L. Zamenhof in 1887, it was intended to be a universal second language for international communi ...

, whose years of work were thrown into the fire by his father because he was afraid that "his son would be thought a spy working code".

Essayist and historian

Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher. A leading writer of the Victorian era, he exerted a profound influence on 19th-century art, literature and philosophy.

Born in Ecclefechan, ...

, lost the only copy of a manuscript for ''

The French Revolution: A History'' when it was mistakenly thrown into the fire by a maid. He wrote it again from the beginning. Writers usually develop a personal schedule.

Angus Wilson

Sir Angus Frank Johnstone-Wilson, CBE (11 August 191331 May 1991) was an English novelist and short story writer. He was one of England's first openly gay authors. He was awarded the 1958 James Tait Black Memorial Prize for '' The Middle Age o ...

, for example, wrote for a number of hours every morning.

Writer's block

Writer's block is a condition, primarily associated with writing, in which an author is either unable to produce new work or experiences a creative slowdown. Mike Rose found that this creative stall is not a result of commitment problems or th ...

is a relatively common experience among writers, especially professional writers, when for a period of time the writer feels unable to write for reasons other than lack of skill or commitment.

Sole

Most writers write alone ŌĆō typically they are engaged in a solitary activity that requires them to struggle with both the concepts they are trying to express and the best way to express it. This may mean choosing the best genre or genres as well as choosing the best words. Writers often develop idiosyncratic solutions to the problem of finding the right words to put on a blank page or screen. "Didn't

Somerset Maugham

William Somerset Maugham ( ; 25 January 1874 ŌĆō 16 December 1965) was an English writer, known for his plays, novels and short stories. Born in Paris, where he spent his first ten years, Maugham was schooled in England and went to a German un ...

also write facing a blank wall? ...

Goethe

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (28 August 1749 ŌĆō 22 March 1832) was a German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, and critic. His works include plays, poetry, literature, and aesthetic criticism, as well as t ...

couldn't write a line if there was another person anywhere in the same house, or so he said at some point."

Collaborative

Collaborative writing means that other authors write and contribute to a part of writing. In this approach, it is highly likely the writers will collaborate on editing the part too. The more usual process is that the editing is done by an independent editor after the writer submits a draft version.

In some cases, such as that between a librettist and composer, a writer will collaborate with another artist on a creative work. One of the best known of these types of collaborations is that between

Gilbert and Sullivan

Gilbert and Sullivan was a Victorian-era theatrical partnership of the dramatist W. S. Gilbert (1836ŌĆō1911) and the composer Arthur Sullivan (1842ŌĆō1900), who jointly created fourteen comic operas between 1871 and 1896, of which '' H.M.S. ...

. Librettist

W. S. Gilbert wrote the words for the

comic opera

Comic opera, sometimes known as light opera, is a sung dramatic work of a light or comic nature, usually with a happy ending and often including spoken dialogue.

Forms of comic opera first developed in late 17th-century Italy. By the 1730s, a n ...

s created by the partnership.

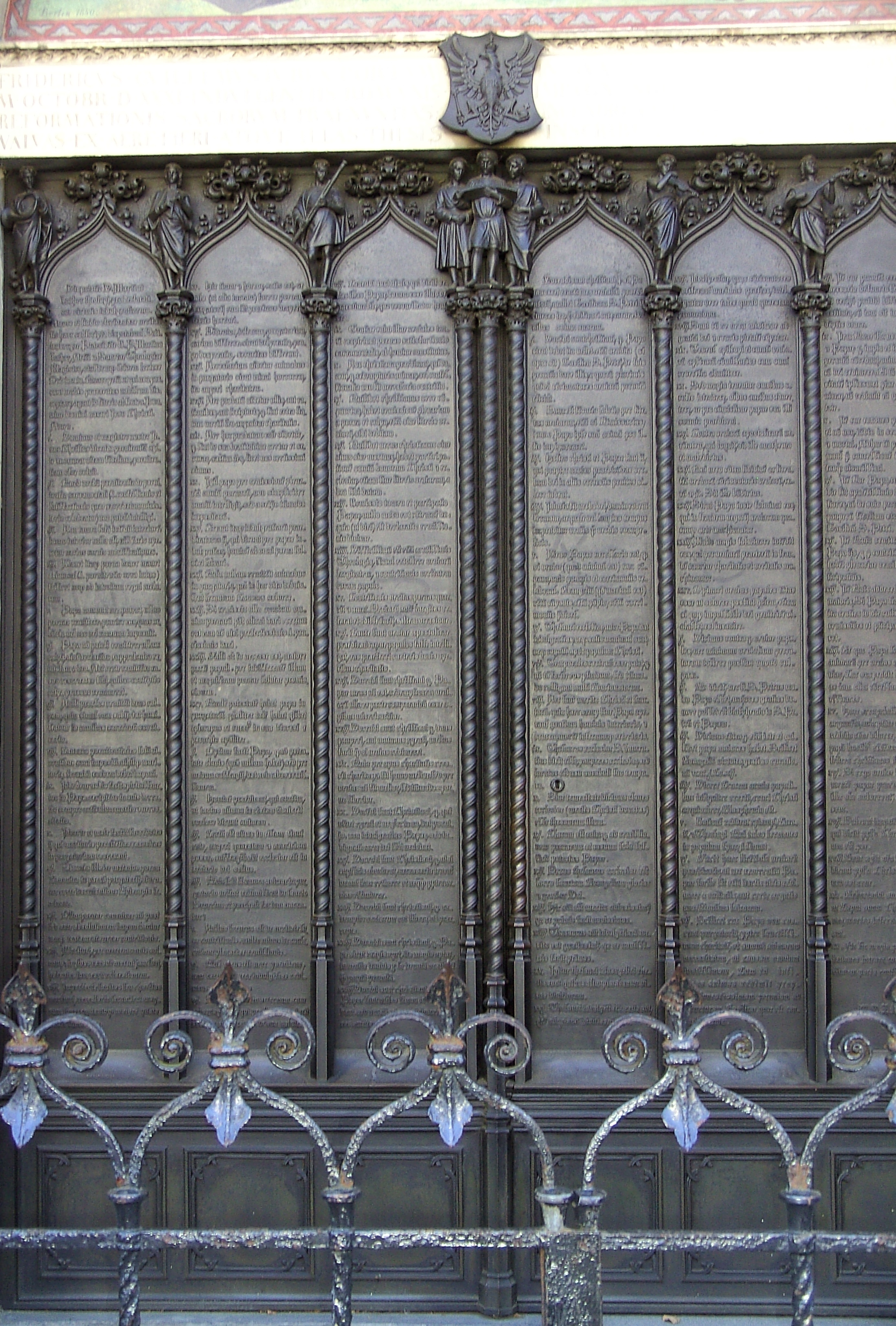

Committee

Occasionally, a writing task is given to a committee of writers. The most best-known example is the task of translating the Bible into English, sponsored by King

James VI

James is a common English language surname and given name:

*James (name), the typically masculine first name James

* James (surname), various people with the last name James

James or James City may also refer to:

People

* King James (disambiguat ...

of England in 1604 and accomplished by six committees, some in

Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge beca ...

and some in

Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the Un ...

, who were allocated different sections of the text. The resulting

Authorized King James Version

The King James Version (KJV), also the King James Bible (KJB) and the Authorized Version, is an English translation of the Christian Bible for the Church of England, which was commissioned in 1604 and published in 1611, by sponsorship of K ...

, published in 1611, has been described as an "everlasting miracle" because its writers (that is, its Translators) sought to "hold themselves consciously poised between the claims of accessibility and beauty, plainness and richness, simplicity and majesty, the people and the king", with the result that the language communicates itself "in a way which is quite unaffected, neither literary nor academic, not historical, nor reconstructionist, but transmitting a nearly incredible immediacy from one end of human civilisation to another."

[(p.240, 243)]

Multimedia

Some writers support the verbal part of their work with images or graphics that are an integral part of the way their ideas are communicated.

William Blake

William Blake (28 November 1757 ŌĆō 12 August 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his life, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of the poetry and visual art of the Romantic Age. ...

is one of rare poets who created his own paintings and drawings as integral parts of works such as his ''

Songs of Innocence and of Experience''.

Cartoonist

A cartoonist is a visual artist who specializes in both drawing and writing cartoons (individual images) or comics (sequential images). Cartoonists differ from comics writers or comic book illustrators in that they produce both the literary an ...

s are writers whose work depends heavily on hand drawn imagery. Other writers, especially writers for children, incorporate painting or drawing in more or less sophisticated ways.

Shaun Tan, for example, is a writer who uses imagery extensively, sometimes combining fact, fiction and illustration, sometimes for a didactic purpose, sometimes on commission.

Children's writers

Beatrix Potter

Helen Beatrix Potter (, 28 July 186622 December 1943) was an English writer, illustrator, natural scientist, and conservationist. She is best known for her children's books featuring animals, such as '' The Tale of Peter Rabbit'', which was ...

,

May Gibbs, and

Theodor Seuss Geisel are as well known for their illustrations as for their texts.

Crowd sourced

Some writers contribute very small sections to a part of writing that cumulates as a result. This method is particularly suited to very large works, such as dictionaries and encyclopaedias. The best known example of the former is the ''

Oxford English Dictionary

The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (''OED'') is the first and foundational historical dictionary of the English language, published by Oxford University Press (OUP). It traces the historical development of the English language, providing a com ...

'', under the editorship of lexicographer

James Murray, who was provided with the prolific and helpful contributions of

W.C. Minor, at the time an inmate of a hospital for the criminally insane.

The best known example of the latter ŌĆō an encyclopaedia that is crowdsourced ŌĆō is Wikipedia, which relies on millions of writers and editors such as

Simon Pulsifer worldwide.

Motivations

Writers have many different reasons for writing, among which is usually some combination of self-expression

and recording facts, history or research results. The many

physician writers, for example, have combined their observation and knowledge of the

human condition

The human condition is all of the characteristics and key events of human life, including birth, learning, emotion, aspiration, morality, conflict, and death. This is a very broad topic that has been and continues to be pondered and analyzed f ...

with their desire to write and contributed many poems, plays, translations, essays and other texts. Some writers write extensively on their motivation and on the likely motivations of other writers. For example,

George Orwell

Eric Arthur Blair (25 June 1903 ŌĆō 21 January 1950), better known by his pen name George Orwell, was an English novelist, essayist, journalist, and critic. His work is characterised by lucid prose, social criticism, opposition to totalita ...

's essay "

Why I Write" (1946) takes this as its subject. As to "what constitutes success or failure to a writer", it has been described as "a complicated business, where the material rubs up against the spiritual, and psychology plays a big part".

Command

Some writers are the authors of specific military orders whose clarity will determine the outcome of a battle. Among the most controversial and unsuccessful was

Lord Raglan's order at the

Charge of the Light Brigade

The Charge of the Light Brigade was a failed military action involving the British light cavalry led by James Brudenell, 7th Earl of Cardigan, Lord Cardigan against Russian forces during the Battle of Balaclava on 25 October 1854 in the Crimea ...

, which being vague and misinterpreted, led to defeat with many casualties.

Develop skill/explore ideas

Some writers use the writing task to develop their own skill (in writing itself or in another area of knowledge) or explore an idea while they are producing a piece of writing.

Philologist

Philology () is the study of language in oral and written historical sources; it is the intersection of textual criticism, literary criticism, history, and linguistics (with especially strong ties to etymology). Philology is also defined as ...

J. R. R. Tolkien, for example, created a new language for his fantasy books.

Entertain

Some genres are a particularly appropriate choice for writers whose chief purpose is to entertain. Among them are

limericks, many comics and

thrillers. Writers of children's literature seek to entertain children but are also usually mindful of the educative function of their work as well.

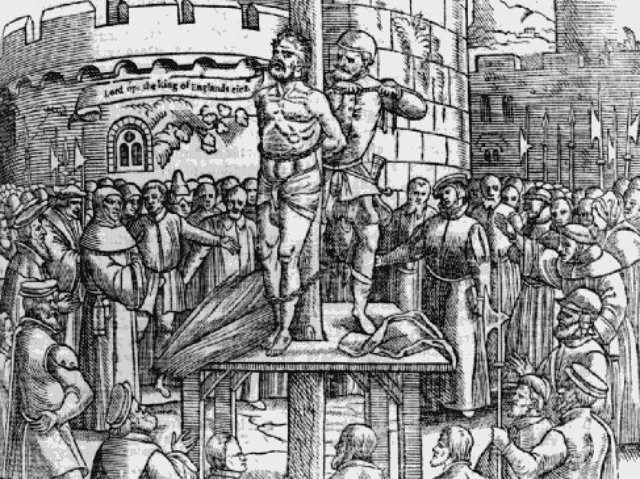

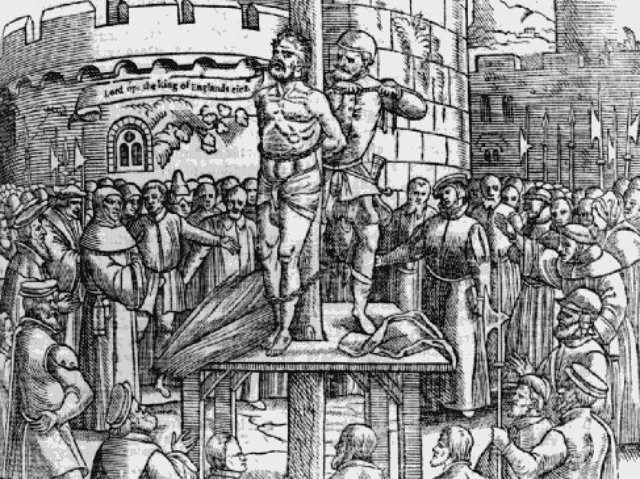

Influence

Anger has motivated many writers, including

Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 ŌĆō 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Luther ...

, angry at religious corruption, who wrote the ''

Ninety-five Theses

The ''Ninety-five Theses'' or ''Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences''-The title comes from the 1517 Basel pamphlet printing. The first printings of the ''Theses'' use an incipit rather than a title which summarizes the content ...

'' in 1517, to reform the church, and

├ēmile Zola

├ēmile ├ēdouard Charles Antoine Zola (, also , ; 2 April 184029 September 1902) was a French novelist, journalist, playwright, the best-known practitioner of the literary school of naturalism, and an important contributor to the development of ...

(1840ŌĆō1902) who wrote the public letter, ''

J'Accuse'' in 1898 to bring public attention to government injustice, as a consequence of which he had to flee to England from his native France. Such writers have affected ideas, opinion or policy significantly.

Payment

Writers may write a particular piece for payment (even if at other times, they write for another reason), such as when they are commissioned to create a new work, transcribe an original one, translate another writer's work, or write for someone who is illiterate or inarticulate. In some cases, writing has been the only way an individual could earn an income.

Frances Trollope is an example of women who wrote to save herself and her family from penury, at a time when there were very few socially acceptable employment opportunities for them. Her book about her experiences in the United States, called ''

Domestic Manners of the Americans'' became a great success, "even though she was over fifty and had never written before in her life" after which "she continued to write hard, carrying this on almost entirely before breakfast".

According to her writer son

Anthony Trollope

Anthony Trollope (; 24 April 1815 ŌĆō 6 December 1882) was an English novelist and civil servant of the Victorian era. Among his best-known works is a series of novels collectively known as the '' Chronicles of Barsetshire'', which revolves ...

"her books saved the family from ruin".

Teach

Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, ß╝łŽü╬╣ŽāŽä╬┐Žä╬Ł╬╗╬ĘŽé ''Aristot├®l─ōs'', ; 384ŌĆō322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical Greece, Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatet ...

, who was tutor to

Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, ß╝ł╬╗╬Ł╬Š╬▒╬Į╬┤Žü╬┐Žé, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC ŌĆō 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

, wrote to support his

teaching

Teaching is the practice implemented by a ''teacher'' aimed at transmitting skills (knowledge, know-how, and interpersonal skills) to a learner, a student, or any other audience in the context of an educational institution. Teaching is closely ...

. He wrote two

treatise

A treatise is a formal and systematic written discourse on some subject, generally longer and treating it in greater depth than an essay, and more concerned with investigating or exposing the principles of the subject and its conclusions." Treat ...

s for the young prince: "On Monarchy", and "On Colonies"

and his

dialogue

Dialogue (sometimes spelled dialog in American English) is a written or spoken conversational exchange between two or more people, and a literary and theatrical form that depicts such an exchange. As a philosophical or didactic device, it is ...

s also appear to have been written either "as lecture notes or discussion papers for use in his philosophy school at the Athens

Lyceum

The lyceum is a category of educational institution defined within the education system of many countries, mainly in Europe. The definition varies among countries; usually it is a type of secondary school. Generally in that type of school the ...

between 334 and 323 BC."

They encompass both his 'scientific' writings (

metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

,

physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which rel ...

,

biology

Biology is the scientific study of life. It is a natural science with a broad scope but has several unifying themes that tie it together as a single, coherent field. For instance, all organisms are made up of cells that process hereditar ...

,

meteorology

Meteorology is a branch of the atmospheric sciences (which include atmospheric chemistry and physics) with a major focus on weather forecasting. The study of meteorology dates back millennia, though significant progress in meteorology did no ...

, and

astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

, as well as

logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from premis ...

and

argument

An argument is a statement or group of statements called premises intended to determine the degree of truth or acceptability of another statement called conclusion. Arguments can be studied from three main perspectives: the logical, the dialect ...

) the 'non-scientific' works (poetry,

oratory, ethics, and politics), and "major elements in traditional

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

and

Roman education".

Writers of

textbook

A textbook is a book containing a comprehensive compilation of content in a branch of study with the intention of explaining it. Textbooks are produced to meet the needs of educators, usually at educational institutions. Schoolbooks are textboo ...

s also use writing to teach and there are numerous instructional guides to writing itself. For example, many people will find it necessary to make a speech "in the service of your company, church, civic club, political party, or other organization" and so, instructional writers have produced texts and guides for speechmaking.

Tell a story

Many writers use their skill to tell the story of their people, community or cultural tradition, especially one with a personal significance. Examples include

Shmuel Yosef Agnon

Shmuel Yosef Agnon ( he, ū®ū×ūĢūÉū£ ūÖūĢūĪūŻ ūóūÆūĀūĢū¤; July 17, 1888 ŌĆō February 17, 1970) was one of the central figures of modern Hebrew literature. In Hebrew, he is known by the acronym Shai Agnon (). In English, his works are published und ...

;

Miguel Ángel Asturias

Miguel ├üngel Asturias Rosales (; October 19, 1899 ŌĆō June 9, 1974) was a Nobel Prize-winning Guatemalan poet-diplomat, novelist, playwright and journalist. Asturias helped establish Latin American literature's contribution to mainstream ...

;

Doris Lessing;

Toni Morrison

Chloe Anthony Wofford Morrison (born Chloe Ardelia Wofford; February 18, 1931 ŌĆō August 5, 2019), known as Toni Morrison, was an American novelist. Her first novel, '' The Bluest Eye'', was published in 1970. The critically acclaimed '' S ...

;

Isaac Bashevis Singer; and

Patrick White

Patrick Victor Martindale White (28 May 1912 ŌĆō 30 September 1990) was a British-born Australian writer who published 12 novels, three short-story collections, and eight plays, from 1935 to 1987.

White's fiction employs humour, florid prose, ...

.

Writers such as

Mario Vargas Llosa

Jorge Mario Pedro Vargas Llosa, 1st Marquess of Vargas Llosa (born 28 March 1936), more commonly known as Mario Vargas Llosa (, ), is a Peruvian novelist, journalist, essayist and former politician, who also holds Spanish citizenship. Vargas Ll ...

,

Herta M├╝ller, and

Erich Maria Remarque

Erich Maria Remarque (, ; born Erich Paul Remark; 22 June 1898 ŌĆō 25 September 1970) was a German-born novelist. His landmark novel '' All Quiet on the Western Front'' (1928), based on his experience in the Imperial German Army during Wor ...

write about the effect of conflict, dispossession and war.

Seek a lover

Writers use prose, poetry, and letters as part of courtship rituals.

Edmond Rostand's play ''

Cyrano de Bergerac

Savinien de Cyrano de Bergerac ( , ; 6 March 1619 ŌĆō 28 July 1655) was a French novelist, playwright, epistolarian, and duelist.

A bold and innovative author, his work was part of the libertine literature of the first half of the 17th c ...

'', written in verse, is about both the power of love and the power of the self-doubting writer/hero's writing talent.

Authorship

Pen names

Writers sometimes use a pseudonym, otherwise known as a pen name or "nom de plume". The reasons they do this include to separate their writing from other work (or other types of writing) for which they are known; to enhance the possibility of publication by reducing prejudice (such as against women writers or writers of a particular race); to reduce personal risk (such as political risks from individuals, groups or states that disagree with them); or to make their name better suit another language.

Examples of well-known writers who used a pen name include:

George Eliot

Mary Ann Evans (22 November 1819 ŌĆō 22 December 1880; alternatively Mary Anne or Marian), known by her pen name George Eliot, was an English novelist, poet, journalist, translator, and one of the leading writers of the Victorian era. She wrot ...

(1819ŌĆō1880), whose real name was Mary Anne (or Marian) Evans;

George Orwell

Eric Arthur Blair (25 June 1903 ŌĆō 21 January 1950), better known by his pen name George Orwell, was an English novelist, essayist, journalist, and critic. His work is characterised by lucid prose, social criticism, opposition to totalita ...

(1903ŌĆō1950), whose real name was Eric Blair;

George Sand

Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin de Francueil (; 1 July 1804 ŌĆō 8 June 1876), best known by her pen name George Sand (), was a French novelist, memoirist and journalist. One of the most popular writers in Europe in her lifetime, bein ...

(1804ŌĆō1876), whose real name was Lucile Aurore Dupin;

Dr. Seuss (1904ŌĆō1991), whose real name was Theodor Seuss Geisel; Stendhal (1783ŌĆō1842), whose real name was Marie-Henri Beyle; and

Mark Twain