Winston Churchill as historian on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Winston Churchill, in addition to his careers of soldier and politician, was a prolific writer under the pen name 'Winston S. Churchill'. After being commissioned into the

Winston Churchill, in addition to his careers of soldier and politician, was a prolific writer under the pen name 'Winston S. Churchill'. After being commissioned into the

In 1895 Winston Churchill was commissioned

In 1895 Winston Churchill was commissioned  As a serving MP he began publishing pamphlets containing his speeches or answers to key parliamentary questions. Beginning with ''Mr Winston Churchill on the Education Bill'' (1902), over 135 such tracts were published over his career. Many of these were subsequently compiled into collections, several of which were edited by his son, Randolph and others of which were edited by

As a serving MP he began publishing pamphlets containing his speeches or answers to key parliamentary questions. Beginning with ''Mr Winston Churchill on the Education Bill'' (1902), over 135 such tracts were published over his career. Many of these were subsequently compiled into collections, several of which were edited by his son, Randolph and others of which were edited by

There are around 135 published booklets of Churchill's individual speeches, including "Mr Winston Churchill on the Education Bill" (1902), "The Fiscal Puzzle: Both Sides Explained by Leading Men'" (1903), "Why I am a Free Trader" (1905) and "Prisons and Prisoners" (1910); the following are speeches published in a collected form.

There are around 135 published booklets of Churchill's individual speeches, including "Mr Winston Churchill on the Education Bill" (1902), "The Fiscal Puzzle: Both Sides Explained by Leading Men'" (1903), "Why I am a Free Trader" (1905) and "Prisons and Prisoners" (1910); the following are speeches published in a collected form.

Collected Churchill Podcasts and speeches

*

The Churchill Centre website

Winston Churchill Memorial and Library

at Westminster College, Missouri

Locations of correspondence and papers of Churchill

at the UK National Archives {{DEFAULTSORT:Churchill, Winston, as writer Bibliographies of British writers

Winston Churchill, in addition to his careers of soldier and politician, was a prolific writer under the pen name 'Winston S. Churchill'. After being commissioned into the

Winston Churchill, in addition to his careers of soldier and politician, was a prolific writer under the pen name 'Winston S. Churchill'. After being commissioned into the 4th Queen's Own Hussars

The 4th Queen's Own Hussars was a cavalry regiment in the British Army, first raised in 1685. It saw service for three centuries, including the First World War and the Second World War. It amalgamated with the 8th King's Royal Irish Hussars, to ...

in 1895, Churchill gained permission to observe the Cuban War of Independence

The Cuban War of Independence (), fought from 1895 to 1898, was the last of three liberation wars that Cuba fought against Spain, the other two being the Ten Years' War (1868–1878) and the Little War (Cuba), Little War (1879–1880). The ...

, and sent war reports to ''The Daily Graphic

''The Daily Graphic: An Illustrated Evening Newspaper'' was the first American newspaper with daily illustrations. It was founded in New York City in 1873 by Canadian engravers George-Édouard Desbarats and William Leggo, and began publicatio ...

''. He continued his war journalism in British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

, at the Siege of Malakand

The siege of Malakand was the 26 July – 2 August 1897 siege of the British garrison in the Malakand region of colonial British India's North West Frontier Province.Nevill p. 232 The British faced a force of Pashtun tribesmen whose tribal lan ...

, then in the Sudan during the Mahdist War

The Mahdist War ( ar, الثورة المهدية, ath-Thawra al-Mahdiyya; 1881–1899) was a war between the Mahdist Sudanese of the religious leader Muhammad Ahmad bin Abd Allah, who had proclaimed himself the "Mahdi" of Islam (the "Guided On ...

and in southern Africa during the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the South ...

.

Churchill's fictional output included one novel and a short story, but his main output comprised non-fiction. After he was elected as an MP, over 130 of his speeches or parliamentary answers were also published in pamphlets or booklets; many were subsequently published in collected editions. Churchill received the Nobel Prize in Literature

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, caption =

, awarded_for = Outstanding contributions in literature

, presenter = Swedish Academy

, holder = Annie Ernaux (2022)

, location = Stockholm, Sweden

, year = 1901 ...

in 1953 "for his mastery of historical and biographical description as well as for brilliant oratory in defending exalted human values".

Writing career

In 1895 Winston Churchill was commissioned

In 1895 Winston Churchill was commissioned cornet

The cornet (, ) is a brass instrument similar to the trumpet but distinguished from it by its conical bore, more compact shape, and mellower tone quality. The most common cornet is a transposing instrument in B, though there is also a so ...

(second lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army until 1 ...

) into the 4th Queen's Own Hussars

The 4th Queen's Own Hussars was a cavalry regiment in the British Army, first raised in 1685. It saw service for three centuries, including the First World War and the Second World War. It amalgamated with the 8th King's Royal Irish Hussars, to ...

. His annual pay was £300, and he calculated he needed an additional £500 to support a style of life equal to that of other officers of the regiment. To earn the required funds, he gained his colonel's agreement to observe the Cuban War of Independence

The Cuban War of Independence (), fought from 1895 to 1898, was the last of three liberation wars that Cuba fought against Spain, the other two being the Ten Years' War (1868–1878) and the Little War (Cuba), Little War (1879–1880). The ...

; his mother, Lady Randolph Churchill

Jennie Spencer-Churchill (; 9 January 1854 – 29 June 1921), known as Lady Randolph Churchill, was an American-born British socialite, the wife of Lord Randolph Churchill, and the mother of British prime minister Sir Winston Churchill.

Earl ...

, used her influence to secure a contract for her son to send war reports to ''The Daily Graphic

''The Daily Graphic: An Illustrated Evening Newspaper'' was the first American newspaper with daily illustrations. It was founded in New York City in 1873 by Canadian engravers George-Édouard Desbarats and William Leggo, and began publicatio ...

''. He was subsequently posted back to his regiment, then based in British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

, where he took part in, and reported on the Siege of Malakand

The siege of Malakand was the 26 July – 2 August 1897 siege of the British garrison in the Malakand region of colonial British India's North West Frontier Province.Nevill p. 232 The British faced a force of Pashtun tribesmen whose tribal lan ...

; the reports were published in '' The Pioneer'' and ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a national British daily broadsheet newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed across the United Kingdom and internationally.

It was f ...

''. The reports formed the basis of his first book, '' The Story of the Malakand Field Force'', which was published in 1898. To relax he also wrote his only novel, '' Savrola'', which was published in 1898. That same year he was transferred to the Sudan to take part in the Mahdist War

The Mahdist War ( ar, الثورة المهدية, ath-Thawra al-Mahdiyya; 1881–1899) was a war between the Mahdist Sudanese of the religious leader Muhammad Ahmad bin Abd Allah, who had proclaimed himself the "Mahdi" of Islam (the "Guided On ...

(1881–1899), where he participated in the Battle of Omdurman

The Battle of Omdurman was fought during the Anglo-Egyptian conquest of Sudan between a British–Egyptian expeditionary force commanded by British Commander-in-Chief ( sirdar) major general Horatio Herbert Kitchener and a Sudanese army of th ...

in September 1898. He published his recollections in ''The River War

''The River War: An Historical Account of the Reconquest of the Soudan'' (1899), by Winston Churchill. It is a history of the conquest of the Sudan between 1896 and 1899 by Anglo-Egyptian forces led by Lord Kitchener. He defeated the Sudanese ...

'' (1899).

In 1899 Churchill resigned his commission and travelled to South Africa as the correspondent with ''The Morning Post

''The Morning Post'' was a conservative daily newspaper published in London from 1772 to 1937, when it was acquired by ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a national British d ...

'', on a salary of £250 a month plus all expenses, to report on the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the South ...

. He was captured by the Boer

Boers ( ; af, Boere ()) are the descendants of the Dutch-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controlled this a ...

s in November that year, but managed to escape. He remained in the country and continued to send in his reports to the newspaper. He subsequently published his despatches in two works, '' London to Ladysmith via Pretoria'' and '' Ian Hamilton's March'' (both 1900). He returned to Britain in 1900 and was elected as the Member of parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house ...

for the Oldham constituency at that year's general election.

As a serving MP he began publishing pamphlets containing his speeches or answers to key parliamentary questions. Beginning with ''Mr Winston Churchill on the Education Bill'' (1902), over 135 such tracts were published over his career. Many of these were subsequently compiled into collections, several of which were edited by his son, Randolph and others of which were edited by

As a serving MP he began publishing pamphlets containing his speeches or answers to key parliamentary questions. Beginning with ''Mr Winston Churchill on the Education Bill'' (1902), over 135 such tracts were published over his career. Many of these were subsequently compiled into collections, several of which were edited by his son, Randolph and others of which were edited by Charles Eade

Charles Eade (10 June 1903 – 27 August 1964) was a British newspaper editor.

Born in Leytonstone, Eade became a subeditor on the '' Daily Chronicle'' at the age of fourteen, then worked on '' Lloyd's Weekly Newspaper'' and the '' Daily Herald'' ...

, the editor of the ''Sunday Dispatch

The ''Sunday Dispatch'' was a prominent British newspaper, published between 27 September 1801 and 18 June 1961. It was ultimately discontinued due to its merger with the ''Sunday Express''.

History

The newspaper was first published as the ''Wee ...

''. In addition to his parliamentary duties, Churchill wrote a two-volume biography of his father, Lord Randolph Churchill

Lord Randolph Henry Spencer-Churchill (13 February 1849 – 24 January 1895) was a British statesman. Churchill was a Tory radical and coined the term ' Tory democracy'. He inspired a generation of party managers, created the National Union o ...

, published in 1906, in which he "presented his father as a tory with increasingly radical sympathies", according to the historian Paul Addison.

In the 1923 general election Churchill lost his parliamentary seat and moved to the south of France where he wrote '' The World Crisis'', a six-volume history of the First World War, published between 1923 and 1931. The book was well-received, although the former Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

Arthur Balfour

Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour, (, ; 25 July 184819 March 1930), also known as Lord Balfour, was a British Conservative statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1902 to 1905. As foreign secretary in the L ...

dismissed the work as "Winston's brilliant autobiography, disguised as world history". At the 1924 general election Churchill returned to the Commons. In 1930 he wrote his first autobiography, '' My Early Life'', after which he began his researches for '' Marlborough: His Life and Times'' (1933–1938), a four-volume biography of his ancestor, John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough

General John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, 1st Prince of Mindelheim, 1st Count of Nellenburg, Prince of the Holy Roman Empire, (26 May 1650 – 16 June 1722 O.S.) was an English soldier and statesman whose career spanned the reign ...

. Before the final volume was published, Churchill wrote a series of biographical profiles for newspapers, which were later collected together and published as ''Great Contemporaries

''Great Contemporaries'' is a collection of 25 short biographical essays about famous people, written by Winston Churchill.

The original collection was published in 1937 and included 21 essays mainly written between 1928 and 1931. Four were a ...

'' (1937).

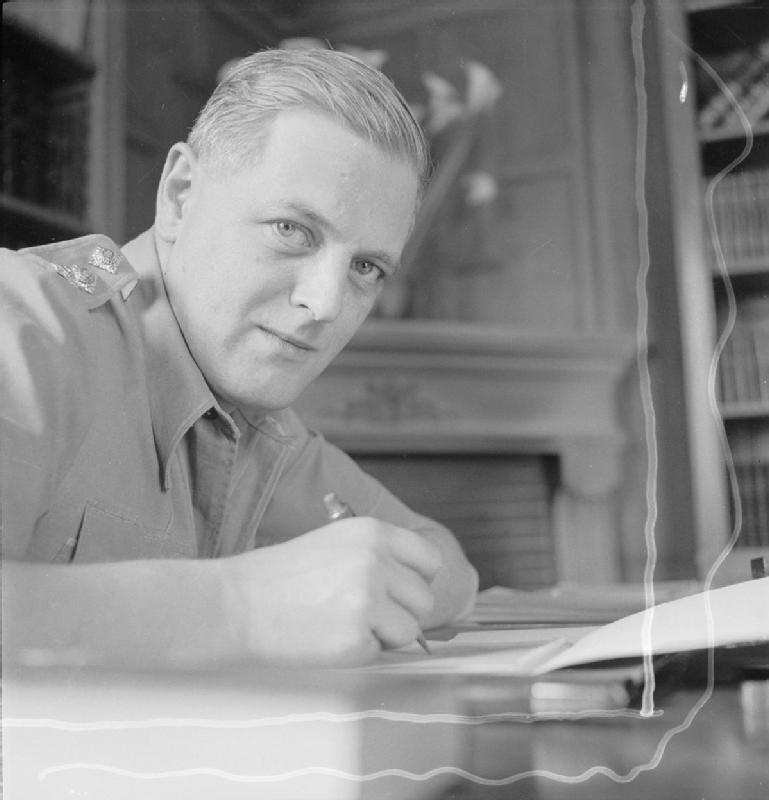

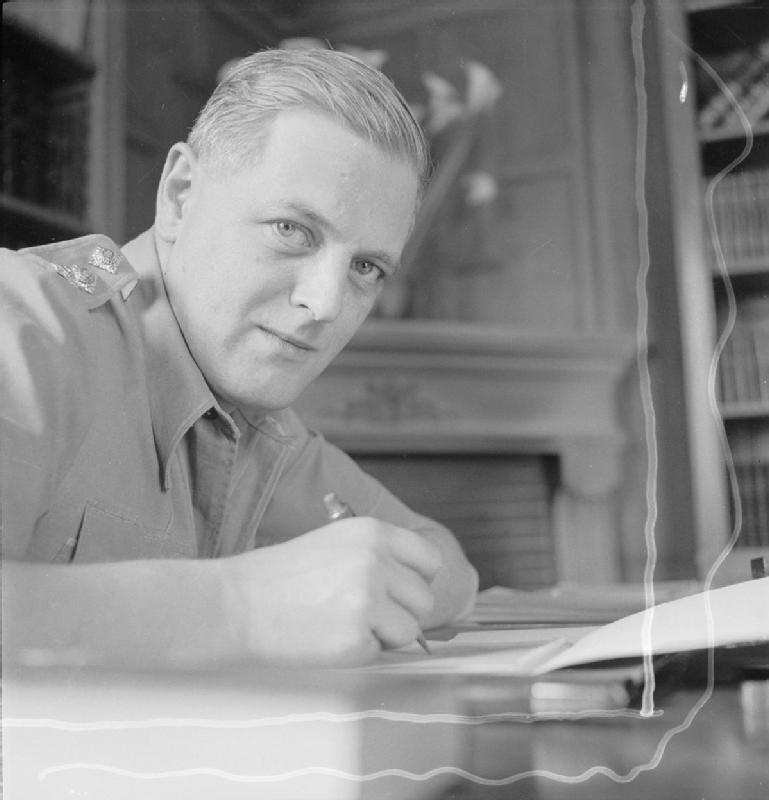

In May 1940, eight months after the outbreak of the Second World War, Churchill became Prime Minister. He wrote no histories during his tenure, although several collections of his speeches were published. At the end of the war he was voted out of office at the 1945 election; he returned to writing and, with a research team headed by the historian William Deakin

Sir Frederick William Dampier Deakin DSO (3 July 1913 – 22 January 2005) was a British historian, World War II veteran, literary assistant to Winston Churchill and the first warden of St Antony's College, Oxford.

Life

Deakin was educate ...

, produced a six-volume history, ''The Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

'' (1948–1953). The books became a best-seller in both the UK and US. Churchill served as Prime Minister for a second time between October 1951 and April 1955 before resigning the premiership; he continued to serve as an MP until 1964. His final major work was the four-volume work ''A History of the English-Speaking Peoples

''A History of the English-Speaking Peoples'' is a four-volume history of Britain and its former colonies and possessions throughout the world, written by Winston Churchill, covering the period from Caesar's invasions of Britain (55 BC) to the e ...

'' (1956–1958). In 1953 Churchill was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, caption =

, awarded_for = Outstanding contributions in literature

, presenter = Swedish Academy

, holder = Annie Ernaux (2022)

, location = Stockholm, Sweden

, year = 1901 ...

"for his mastery of historical and biographical description as well as for brilliant oratory in defending exalted human values". Churchill was almost always well paid as an author and, for most of his life, writing was his main source of income. He produced a huge portfolio of written work; the journalist and historian Paul Johnson estimates that Churchill wrote an estimated eight to ten million words in more than forty books, thousands of newspaper and magazine articles, and at least two film scripts. John Gunther

John Gunther (August 30, 1901 – May 29, 1970) was an American journalist and writer.

His success came primarily by a series of popular sociopolitical works, known as the "Inside" books (1936–1972), including the best-selling '' Ins ...

in 1939 estimated that he earned $100,000 a year ($ in ) from writing and lecturing, but that "of this he spends plenty".

When demand was high for his newspaper and magazine articles, Churchill employed a ghostwriter

A ghostwriter is hired to write literary or journalistic works, speeches, or other texts that are officially credited to another person as the author. Celebrities, executives, participants in timely news stories, and political leaders ofte ...

.David Lough, ''No More Champagne: Churchill and his Money'' (London: Head of Zeus, 2015) During 1934, for example, Churchill was commissioned by ''Collier's

''Collier's'' was an American general interest magazine founded in 1888 by Peter F. Collier, Peter Fenelon Collier. It was launched as ''Collier's Once a Week'', then renamed in 1895 as ''Collier's Weekly: An Illustrated Journal'', shortened i ...

'', the ''News of the World

The ''News of the World'' was a weekly national Tabloid journalism#Red tops, red top Tabloid (newspaper format), tabloid newspaper published every Sunday in the United Kingdom from 1843 to 2011. It was at one time the world's highest-selling En ...

'', the ''Daily Mail

The ''Daily Mail'' is a British daily middle-market tabloid newspaper and news websitePeter Wilb"Paul Dacre of the Daily Mail: The man who hates liberal Britain", ''New Statesman'', 19 December 2013 (online version: 2 January 2014) publish ...

'' - and, added that year, the ''Sunday Dispatch

The ''Sunday Dispatch'' was a prominent British newspaper, published between 27 September 1801 and 18 June 1961. It was ultimately discontinued due to its merger with the ''Sunday Express''.

History

The newspaper was first published as the ''Wee ...

'', for which the newspaper's editor, William Blackwood, employed Adam Marshall Diston to rework Churchill's old material (Churchill himself would write one new piece in every four published by the ''Dispatch''). Later in the year, when Churchill had less time to write, at the recommendation of Blackwood he employed Diston directly as his ghostwriter. Diston wrote, for example, Churchill's remaining ''Collier's'' articles for the year, being paid £15 from the £350 commission Churchill received for each article. Blackwood considered Diston a 'splendid journalist' and his first article written for Churchill went to print without change - this, according to David Lough, 'was the start of a partnership that would flourish for the rest of the decade'. By the end of the following year, Diston had already prepared most of Churchill's 'The Great Men I Have Known' series for the ''News of the World'' in Britain and ''Collier's'' in the US, due to appear from January 1936. Sir Emsley Carr, the British newspaper's chairman, enjoyed them so much he immediately signed up Churchill for a series in 1937. The ''News of the World'' would pay nearly £400 (£12,000 today) an article. Another of Churchill's ghostwriters was his Private Secretary

A private secretary (PS) is a civil servant in a governmental department or ministry, responsible to a secretary of state or minister; or a public servant in a royal household, responsible to a member of the royal family.

The role exists in t ...

Edward Marsh (who would at times receive up to 10% of Churchill's commission).Roy Jenkins, ''Churchill: A Biography'' (Pan Macmillan, 2012)Frederick Woods, ''Artillery of Words: The Writings of Sir Winston Churchill'' (London: Leo Copper, 1992)

American novelist of the same name

In the late 1890s, Churchill's writings first came to be confused with those of his American contemporary Winston Churchill, a best-selling novelist. He wrote to his American counterpart about the confusion their names were causing among their readers, offering to sign his own works "Winston Spencer Churchill", adding the first half of his double-barrelled surname, Spencer-Churchill, which he did not otherwise use. After a few early editions the middle name was turned into an initial, his pen name subsequently appearing as "Winston S. Churchill". The two men met on occasions when one of them happened to be in the other's country, but their diametrically opposed personalities prevented the development of a close friendship.Non-fiction

Fiction

Collected speeches

There are around 135 published booklets of Churchill's individual speeches, including "Mr Winston Churchill on the Education Bill" (1902), "The Fiscal Puzzle: Both Sides Explained by Leading Men'" (1903), "Why I am a Free Trader" (1905) and "Prisons and Prisoners" (1910); the following are speeches published in a collected form.

There are around 135 published booklets of Churchill's individual speeches, including "Mr Winston Churchill on the Education Bill" (1902), "The Fiscal Puzzle: Both Sides Explained by Leading Men'" (1903), "Why I am a Free Trader" (1905) and "Prisons and Prisoners" (1910); the following are speeches published in a collected form.

Miscellany

Notes and references

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * *External links

* * * *Collected Churchill Podcasts and speeches

*

The Churchill Centre website

Winston Churchill Memorial and Library

at Westminster College, Missouri

Locations of correspondence and papers of Churchill

at the UK National Archives {{DEFAULTSORT:Churchill, Winston, as writer Bibliographies of British writers

Writer

A writer is a person who uses written words in different writing styles and techniques to communicate ideas. Writers produce different forms of literary art and creative writing such as novels, short stories, books, poetry, travelogues, pla ...