William Whiston on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

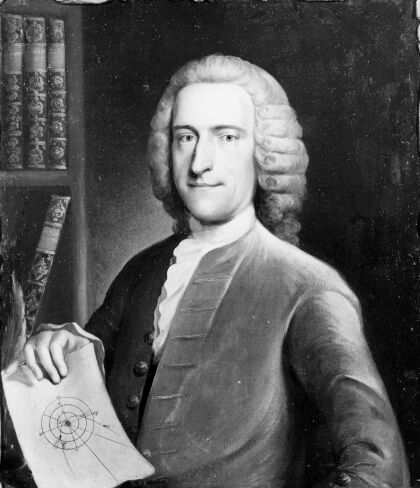

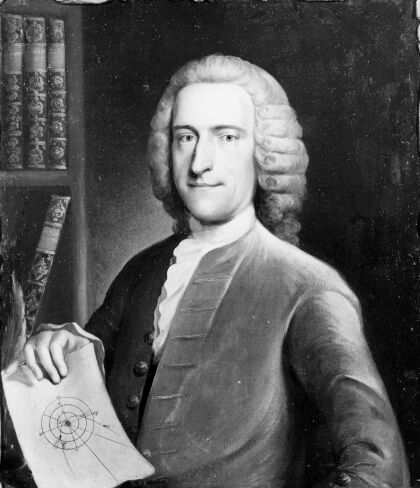

William Whiston (9 December 166722 August 1752) was an English theologian, historian,

In 1707 Whiston was

In 1707 Whiston was

Whiston founded a society for promoting primitive Christianity, lecturing in support of his theories in halls and coffee-houses at London, Bath, and

Whiston founded a society for promoting primitive Christianity, lecturing in support of his theories in halls and coffee-houses at London, Bath, and

His lectures were often accompanied by publications. In 1712, he published, with

His lectures were often accompanied by publications. In 1712, he published, with

Whiston's later life was spent in continual controversy:

Whiston's later life was spent in continual controversy:

Biography of William Whiston

at the LucasianChair.org, the homepage of the

Bibliography for William Whiston

at the LucasianChair.org the homepage of the Lucasian Chair of Mathematics at Cambridge University

* * * *

"Account of Newton"

''Collection of Authentick Records'' (1728), pp. 1070–1082

"The Works of Flavius Josephus"

translated by William Whiston

by

"Whiston's Flood"

"William Whiston, The Universal Deluge, and a Terrible Specracle" by Roomet Jakapi

''Collection of Authentick Records'' by Whiston at the Newton Project

Collection of William Whiston portraits

at England's National Portrait Gallery

Primitive New Testament

William Whiston | Portraits From the Past''A New Theory of the Earth''

(1696) – full digital facsimile at Linda Hall Library {{DEFAULTSORT:Whiston, William 1667 births 1752 deaths 17th-century apocalypticists 17th-century English mathematicians 18th-century apocalypticists 18th-century English mathematicians Alumni of Clare College, Cambridge Catastrophism Chronologists English Baptists Lucasian Professors of Mathematics People from Hinckley and Bosworth (district) Post-Reformation Arian Christians

natural philosopher

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe. It was dominant before the development of modern science.

From the ancient wo ...

, and mathematician

A mathematician is someone who uses an extensive knowledge of mathematics in their work, typically to solve mathematical problems.

Mathematicians are concerned with numbers, data, quantity, structure, space, models, and change.

History

On ...

, a leading figure in the popularisation of the ideas of Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author (described in his time as a " natural philosopher"), widely recognised as one of the grea ...

. He is now probably best known for helping to instigate the Longitude Act

The Longitude Act 1714 was an Act of Parliament of Great Britain passed in July 1714 at the end of the reign of Anne, Queen of Great Britain, Queen Anne. It established the Board of Longitude and offered monetary Bounty (reward), rewards (Longitud ...

in 1714 (and his attempts to win the rewards that it promised) and his important translations of the '' Antiquities of the Jews'' and other works by Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; grc-gre, Ἰώσηπος, ; 37 – 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for '' The Jewish War'', who was born in Jerusalem—then part of Roman Judea—to a father of priestly ...

(which are still in print). He was a prominent exponent of Arianism and wrote ''A New Theory of the Earth

''A New Theory of the Earth'' was a book written by William Whiston, in which he presented a description of the divine creation of the Earth and a posited global flood. He also postulated that the earth originated from the atmosphere of a comet ...

''.

Whiston succeeded his mentor Newton as Lucasian Professor of Mathematics

The Lucasian Chair of Mathematics () is a mathematics professorship in the University of Cambridge, England; its holder is known as the Lucasian Professor. The post was founded in 1663 by Henry Lucas, who was Cambridge University's Member of Pa ...

at the University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

. In 1710 he lost the professorship and was expelled from the university as a result of his unorthodox religious views. Whiston rejected the notion of eternal torment in hellfire, which he viewed as absurd, cruel, and an insult to God. What especially pitted him against church authorities was his denial of the doctrine of the Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God th ...

, which he believed had pagan origins.

Early life and career

Whiston was born to Josiah Whiston (1622–1685) and Katherine Rosse (1639–1701) at Norton-juxta-Twycross, inLeicestershire

Leicestershire ( ; postal abbreviation Leics.) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in the East Midlands, England. The county borders Nottinghamshire to the north, Lincolnshire to the north-east, Rutland to the east, Northamptonshire t ...

, where his father was rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

. His mother was daughter of the previous rector at Norton-juxta-Twycross, Gabriel Rosse. Josiah Whiston was a presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

, but retained his rectorship after the Stuart Restoration

The Restoration of the Stuart monarchy in the kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland took place in 1660 when King Charles II returned from exile in continental Europe. The preceding period of the Protectorate and the civil wars came to ...

in 1660. William Whiston was educated privately, for his health, and so that he could act as amanuensis to his blind father. He studied at Queen Elizabeth Grammar School at Tamworth, Staffordshire

Tamworth (, ) is a market town and borough in Staffordshire, England, north-east of Birmingham. The town borders North Warwickshire to the east and north, Lichfield to the north, south-west and west. The town takes its name from the River T ...

. After his father's death, he entered Clare College, Cambridge

Clare College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge in Cambridge, England. The college was founded in 1326 as University Hall, making it the second-oldest surviving college of the University after Peterhouse. It was refound ...

as a sizar

At Trinity College, Dublin and the University of Cambridge, a sizar is an undergraduate who receives some form of assistance such as meals, lower fees or lodging during his or her period of study, in some cases in return for doing a defined jo ...

in 1686. He applied himself to mathematical study, was awarded the degree of Bachelor of Arts (BA) (1690), and AM (1693), and was elected Fellow in 1691 and probationary senior Fellow in 1693.

William Lloyd ordained Whiston at Lichfield

Lichfield () is a cathedral city and civil parish in Staffordshire, England. Lichfield is situated roughly south-east of the county town of Stafford, south-east of Rugeley, north-east of Walsall, north-west of Tamworth and south-west o ...

in 1693. In 1694, claiming ill health, he resigned his tutorship at Clare to Richard Laughton

Richard Laughton (1670?–1723) was an English churchman and academic, now known as a natural philosopher and populariser of the ideas of Isaac Newton.

Early life

Originally from London, he was educated at Clare College, Cambridge, where he was a ...

, chaplain to John Moore, the bishop of Norwich

The Bishop of Norwich is the ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Norwich in the Province of Canterbury. The diocese covers most of the county of Norfolk and part of Suffolk. The bishop of Norwich is Graham Usher.

The see is in t ...

, and swapped positions with him. He now divided his time between Norwich, Cambridge and London. In 1698 Moore gave him the living of Lowestoft where he became rector. In 1699 he resigned his Fellowship of Clare College and left to marry.

Whiston first met Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author (described in his time as a " natural philosopher"), widely recognised as one of the grea ...

in 1694 and attended some of his lectures, though he first found them, by his own admission, incomprehensible. Encouraged after reading a paper by David Gregory on Newtonian philosophy, he set out to master Newton's ''Principia mathematica

The ''Principia Mathematica'' (often abbreviated ''PM'') is a three-volume work on the foundations of mathematics written by mathematician–philosophers Alfred North Whitehead and Bertrand Russell and published in 1910, 1912, and 1913. ...

'' thereafter. He and Newton became friends. In 1701 Whiston resigned his living to become Isaac Newton's substitute, giving the Lucasian lectures at Cambridge. He succeeded Newton as Lucasian professor in 1702. There followed a period of joint research with Roger Cotes

Roger Cotes (10 July 1682 – 5 June 1716) was an English mathematician, known for working closely with Isaac Newton by proofreading the second edition of his famous book, the '' Principia'', before publication. He also invented the quadratur ...

, appointed with Whiston's patronage to the Plumian professorship in 1706. Students at the Cotes–Whiston experimental philosophy course included Stephen Hales

Stephen Hales (17 September 16774 January 1761) was an English clergyman who made major contributions to a range of scientific fields including botany, pneumatic chemistry and physiology. He was the first person to measure blood pressure. He al ...

, William Stukeley, and Joseph Wasse

Joseph Wasse (1672–1738) was an English cleric and classical scholar.

Life

He was born in Yorkshire, and entered Queens' College, Cambridge as a sizar in 1691. He became bible clerk in 1694, scholar in 1695, was B.A. in 1694, fellow and M.A. in ...

.

Newtonian theologian

In 1707 Whiston was

In 1707 Whiston was Boyle lecturer

The Boyle Lectures are named after Robert Boyle, a prominent natural philosopher of the 17th century and son of Richard Boyle, 1st Earl of Cork. Under the terms of his Will, Robert Boyle endowed a series of lectures or sermons (originally eight e ...

; this lecture series was at the period a significant opportunity for Newton's followers, including Richard Bentley and Samuel Clarke

Samuel Clarke (11 October 1675 – 17 May 1729) was an English philosopher and Anglican cleric. He is considered the major British figure in philosophy between John Locke and George Berkeley.

Early life and studies

Clarke was born in Norwich, ...

, to express their views, especially in opposition to the rise of deism. The "Newtonian" line came to include, with Bentley, Clarke and Whiston in particular, a defence of natural law

Natural law ( la, ius naturale, ''lex naturalis'') is a system of law based on a close observation of human nature, and based on values intrinsic to human nature that can be deduced and applied independently of positive law (the express enacte ...

by returning to the definition of Augustine of Hippo of a miracle

A miracle is an event that is inexplicable by natural or scientific lawsOne dictionary define"Miracle"as: "A surprising and welcome event that is not explicable by natural or scientific laws and is therefore considered to be the work of a divi ...

(a cause of human wonderment), rather than the prevailing concept of a divine intervention against nature, which went back to Anselm. This move was intended to undermine arguments of deists and sceptics. The Boyle lectures dwelt on the connections between biblical prophecies, dramatic physical events such as floods and eclipses, and their explanations in terms of science. On the other hand, Whiston was alive to possible connections of prophecy with current affairs: the War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict that took place from 1701 to 1714. The death of childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700 led to a struggle for control of the Spanish Empire between his heirs, Phil ...

, and later the Jacobite rebellions

, war =

, image = Prince James Francis Edward Stuart by Louis Gabriel Blanchet.jpg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = James Francis Edward Stuart, Jacobite claimant between 1701 and 1766

, active ...

.

Whiston supported a qualified biblical literalism

Biblical literalism or biblicism is a term used differently by different authors concerning biblical interpretation. It can equate to the dictionary definition of literalism: "adherence to the exact letter or the literal sense", where literal mea ...

: the literal meaning should be the default, unless there was a good reason to think otherwise. This view again went back to Augustine. Newton's attitude to the cosmogony of Thomas Burnet

Thomas Burnet (c. 1635? – 27 September 1715) was an English theologian and writer on cosmogony.

Life

He was born at Croft near Darlington in 1635. After studying at Northallerton Grammar School under Thomas Smelt, he went to Clare Colle ...

reflected on the language of the Genesis creation narrative; as did Whiston's alternative cosmogony. Moses as author of ''Genesis'' was not necessarily writing as a natural philosopher, nor as a law-giver, but for a particular audience. The new cosmogonies of Burnet, Whiston and John Woodward John Woodward or ''variant'', may refer to:

Sports

* John Woodward (English footballer) (born 1947), former footballer

* John Woodward (Scottish footballer) (born 1949), former footballer

* Johnny Woodward (1924–2002), English footballer

* Jo ...

were all criticised for their disregard of the biblical account, by John Arbuthnot, John Edwards

Johnny Reid Edwards (born June 10, 1953) is an American lawyer and former politician who served as a U.S. senator from North Carolina. He was the Democratic nominee for vice president in 2004 alongside John Kerry, losing to incumbents George ...

and William Nicolson

William Nicolson (1655–1727) was an English churchman, linguist and antiquarian. As a bishop he played a significant part in the House of Lords during the reign of Queen Anne, and left a diary that is an important source for the politics of ...

in particular.

The title for Whiston's Boyle lectures was ''The Accomplishment of Scripture Prophecies''. Rejecting typological interpretation of biblical prophecy, he argued that the meaning of a prophecy must be unique. His views were later challenged by Anthony Collins. There was a more immediate attack by Nicholas Clagett

Nicholas Clagett (14 April 1686 – 8 December 1746) was an English bishop.

Life

Claggett was from a clerical family of Bury St Edmunds. He went up to Trinity College, Cambridge aged 16 in April 1702, graduating B.A. in 1705–6, M.A. in 1 ...

in 1710. One reason prophecy was topical was the Camisard

Camisards were Huguenots (French Protestants) of the rugged and isolated Cévennes region and the neighbouring Vaunage in southern France. In the early 1700s, they raised a resistance against the persecutions which followed Louis XIV's Revocation ...

movement that saw French exiles ("French prophets") in England. Whiston had started writing on the millenarianism that was integral to the Newtonian theology, and wanted to distance his views from theirs, and in particular from those of John Lacy. Meeting the French prophets in 1713, Whiston developed the view that the charismatic gift of revelation could be demonic possession.

Tensions with Newton

It is no longer assumed that Whiston's ''Memoirs'' are completely trustworthy on the matter of his personal relations with Newton. One view is that the relationship was never very close, Bentley being more involved in Whiston's appointment to the Lucasian chair; and that it deteriorated as soon as Whiston began to write on prophecy, publishing ''Essay on the Revelation of St John'' (1706). This work proclaimed the millennium for the year 1716. Whiston's 1707 edition of Newton's '' Arithmetica Universalis'' did nothing to improve matters. Newton himself was heavily if covertly involved in the 1722 edition, nominally due to John Machin, making many changes. In 1708–9 Whiston was engagingThomas Tenison

Thomas Tenison (29 September 163614 December 1715) was an English church leader, Archbishop of Canterbury from 1694 until his death. During his primacy, he crowned two British monarchs.

Life

He was born at Cottenham, Cambridgeshire, the son a ...

and John Sharp as archbishops in debates on the Trinity. There is evidence from Hopton Haynes that Newton reacted by pulling back from publication on the issue; his antitrinitarian

Nontrinitarianism is a form of Christianity that rejects the mainstream Christian doctrine of the Trinity—the belief that God is three distinct hypostases or persons who are coeternal, coequal, and indivisibly united in one being, or essen ...

views, from the 1690s, were finally published in 1754 as ''An Historical Account of Two Notable Corruptions of Scripture

''An Historical Account of Two Notable Corruptions of Scripture'' is a dissertation by the English mathematician and scholar Isaac Newton. This was sent in a letter to John Locke on 14 November 1690. In fact, Newton may have been in dialogue w ...

''.

Whiston was never a Fellow of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

. In conversation with Edmond Halley

Edmond (or Edmund) Halley (; – ) was an English astronomer, mathematician and physicist. He was the second Astronomer Royal in Britain, succeeding John Flamsteed in 1720.

From an observatory he constructed on Saint Helena in 1676–77, H ...

he blamed his reputation as a "heretick". Also, though, he claimed Newton had disliked having an independent-minded disciple; and was unnaturally cautious and suspicious by nature.

Expelled Arian

Whiston's route to rejection of the Nicene Creed, the historical orthodox position against Arianism, began early in his tenure of the Lucasian chair as he followed hints fromSamuel Clarke

Samuel Clarke (11 October 1675 – 17 May 1729) was an English philosopher and Anglican cleric. He is considered the major British figure in philosophy between John Locke and George Berkeley.

Early life and studies

Clarke was born in Norwich, ...

. He read also in Louis Ellies Dupin Louis Ellies du Pin or Dupin (17 June 1657 – 6 June 1719) was a French ecclesiastical historian, who was responsible for the ''Nouvelle bibliothèque des auteurs ecclésiastiques''.

Childhood and education

Dupin was born at Paris, coming from a ...

, and the ''Explication of Gospel Theism'' (1706) of Richard Brocklesby

Richard Brocklesby (11 August 1722 – 11 December 1797), an English physician, was born at Minehead, Somerset.

He was educated at Ballitore, in Ireland, where Edmund Burke was one of his school fellows, studied medicine at Edinburgh, and f ...

. His study of the '' Apostolic Constitutions'' then convinced him that Arianism was the creed of the early church.

The general election of 1710 brought the Tories

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. The ...

solid political power for a number of years, up to the Hanoverian succession

The Act of Settlement is an Act of the Parliament of England that settled the succession to the English and Irish crowns to only Protestants, which passed in 1701. More specifically, anyone who became a Roman Catholic, or who married one, bec ...

of 1714. Their distrust of theological innovation had a direct impact on Whiston, as well as others of similar views. His heterodoxy was notorious. In 1710 he was deprived of his professorship and expelled from the university.

The matter was not allowed to rest there: Whiston tried to get a hearing before Convocation. He did have defenders even in the high church

The term ''high church'' refers to beliefs and practices of Christian ecclesiology, liturgy, and theology that emphasize formality and resistance to modernisation. Although used in connection with various Christian traditions, the term originate ...

ranks, such as George Smalridge

George Smalridge (''alias'' Smallridge; 18 May 1662 – 27 September 1719) was Bishop of Bristol (1714–1719).

Life

Smalridge was born at Lichfield, son of the Sheriff of Lichfield Thomas Smalridge, George received his early education, this b ...

. For political reasons, this development would have been divisive at the time. Queen Anne made a point of twice "losing" the papers in the case. After her death in 1714 the intended hearing was allowed to drop. The party passions of these years found an echo in Henry Sacheverell

Henry Sacheverell (; 8 February 1674 – 5 June 1724) was an English high church Anglican clergyman who achieved nationwide fame in 1709 after preaching an incendiary 5 November sermon. He was subsequently impeached by the House of Commons and ...

's attempt to exclude Whiston from his church of St Andrew's, Holborn, taking place in 1719.

"Primitive Christianity"

Whiston founded a society for promoting primitive Christianity, lecturing in support of his theories in halls and coffee-houses at London, Bath, and

Whiston founded a society for promoting primitive Christianity, lecturing in support of his theories in halls and coffee-houses at London, Bath, and Tunbridge Wells

Royal Tunbridge Wells is a town in Kent, England, southeast of central London. It lies close to the border with East Sussex on the northern edge of the High Weald, whose sandstone geology is exemplified by the rock formation High Rocks. T ...

. Those he involved included Thomas Chubb

Thomas Chubb (29 September 16798 February 1747) was a lay English Deist writer born near Salisbury. He saw Christ as a divine teacher, but held reason to be sovereign over religion. He questioned the morality of religions, while defending Chris ...

, Thomas Emlyn

Thomas Emlyn (1663–1741) was an English nonconformist divine.

Life

Emlyn was born at Stamford, Lincolnshire. He served as chaplain to the presbyterian Letitia, countess of Donegal, the daughter of Sir William Hicks, 1st Baronet who married ...

, John Gale, Benjamin Hoadley, Arthur Onslow

Arthur Onslow (1 October 169117 February 1768) was an English politician. He set a record for length of service when repeatedly elected to serve as Speaker of the House of Commons, where he was known for his integrity.

Early life and educat ...

, and Thomas Rundle

Thomas Rundle (c.1688–1743) was an English cleric suspected of unorthodox views. He became Anglican bishop of Derry not long after a high-profile controversy had prevented his becoming bishop of Gloucester in 1733.

Early life

He was born at Milt ...

. There were meetings at Whiston's house from 1715 to 1717; Hoadley avoided coming, as did Samuel Clarke, though invited. A meeting with Clarke, Hoadley, John Craig and Gilbert Burnet the younger had left these leading latitudinarian

Latitudinarians, or latitude men, were initially a group of 17th-century English theologiansclerics and academicsfrom the University of Cambridge who were moderate Anglicans (members of the Church of England). In particular, they believed that ...

s unconvinced about Whiston's reliance on the ''Apostolical Constitutions''.

Franz Wokenius wrote a 1728 Latin work on Whiston's view of primitive Christianity. His challenge to the teachings of Athanasius

Athanasius I of Alexandria, ; cop, ⲡⲓⲁⲅⲓⲟⲥ ⲁⲑⲁⲛⲁⲥⲓⲟⲩ ⲡⲓⲁⲡⲟⲥⲧⲟⲗⲓⲕⲟⲥ or Ⲡⲁⲡⲁ ⲁⲑⲁⲛⲁⲥⲓⲟⲩ ⲁ̅; (c. 296–298 – 2 May 373), also called Athanasius the Great, ...

meant that Whiston was commonly considered heretical

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

on many points. On the other hand, he was a firm believer in supernatural aspects of Christianity. He defended prophecy and miracle. He supported anoint

Anointing is the ritual act of pouring aromatic oil over a person's head or entire body.

By extension, the term is also applied to related acts of sprinkling, dousing, or smearing a person or object with any perfumed oil, milk, butter, or ot ...

ing the sick and touching for the king's evil. His dislike of rationalism

In philosophy, rationalism is the epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or "any view appealing to reason as a source of knowledge or justification".Lacey, A.R. (1996), ''A Dictionary of Philosophy ...

in religion also made him one of the numerous opponents of Hoadley's ''Plain Account of the Nature and End of the Sacrament''. He was fervent in his views of ecclesiastical government and discipline, derived from the ''Apostolical Constitutions''.

Around 1747, when his clergyman began to read the Athanasian Creed, which Whiston did not believe in, he physically left the church and the Anglican communion

The Anglican Communion is the third largest Christian communion after the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches. Founded in 1867 in London, the communion has more than 85 million members within the Church of England and other ...

, becoming a Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only ( believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul compe ...

.

By the 1720s, some dissenter

A dissenter (from the Latin ''dissentire'', "to disagree") is one who dissents (disagrees) in matters of opinion, belief, etc.

Usage in Christianity

Dissent from the Anglican church

In the social and religious history of England and Wales, and ...

s and early Unitarians viewd Whiston as a role model.

Lecturer and popular author

Whiston began lecturing on natural philosophy in London. He gave regular courses atcoffee house

A coffeehouse, coffee shop, or café is an establishment that primarily serves coffee of various types, notably espresso, latte, and cappuccino. Some coffeehouses may serve cold drinks, such as iced coffee and iced tea, as well as other non- ...

s, particularly Button's, and also at the Censorium, a set of riverside meeting rooms in London run by Richard Steele

Sir Richard Steele (bap. 12 March 1672 – 1 September 1729) was an Anglo-Irish writer, playwright, and politician, remembered as co-founder, with his friend Joseph Addison, of the magazine ''The Spectator''.

Early life

Steele was born in D ...

. At Button's, he gave courses of demonstration lectures on astronomical and physical phenomena, and Francis Hauksbee the younger worked with him on experimental demonstrations. His passing remarks on religious topics were sometimes objected to, for example by Henry Newman writing to Steele.

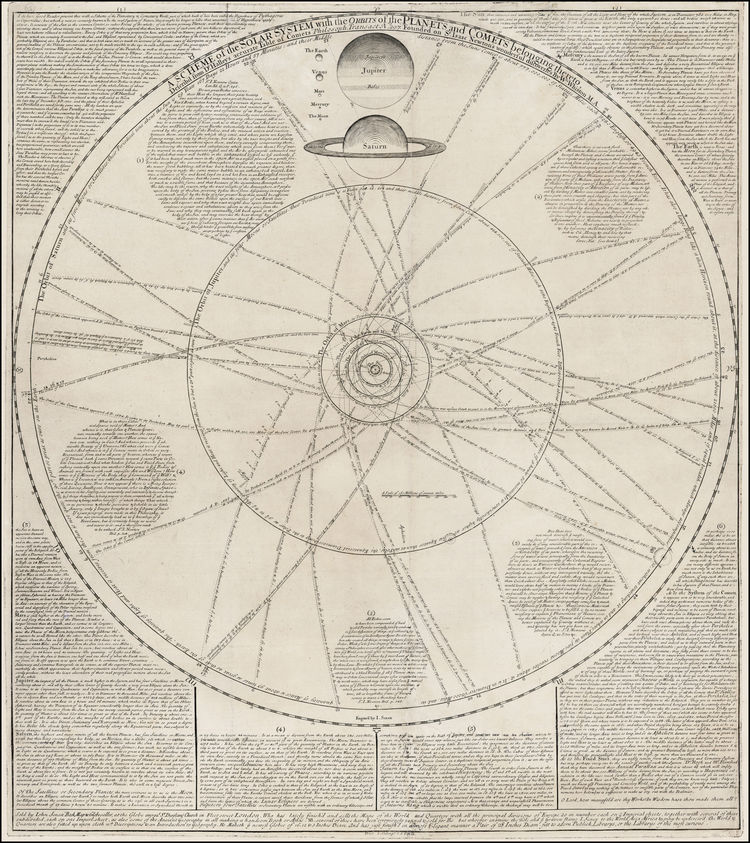

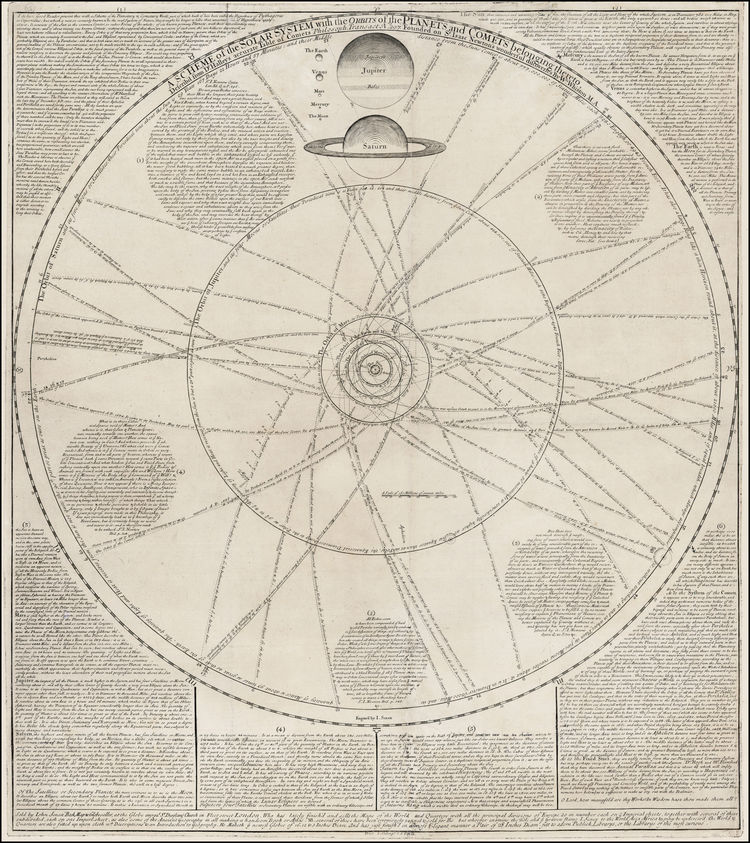

His lectures were often accompanied by publications. In 1712, he published, with

His lectures were often accompanied by publications. In 1712, he published, with John Senex

John Senex (1678 in Ludlow, Shropshire – 1740 in London) was an English cartographer, engraver and explorer.

He was also an astrologer, geologist, and geographer to Queen Anne of Great Britain, editor and seller of antique maps and most import ...

, a chart of the Solar System

The Solar System Capitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Solar ...

showing numerous paths of comets. In 1715, he lectured on the total solar eclipse of 3 May 1715 (which fell in April Old Style

Old Style (O.S.) and New Style (N.S.) indicate dating systems before and after a calendar change, respectively. Usually, this is the change from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar as enacted in various European countries between 158 ...

in England); Whiston lectured on it at the time, in Covent Garden

Covent Garden is a district in London, on the eastern fringes of the West End, between St Martin's Lane and Drury Lane. It is associated with the former fruit-and-vegetable market in the central square, now a popular shopping and tourist si ...

, and later, as a natural event and as a portent.

By 1715 Whiston had also become adept at newspaper advertising. He frequently lectured to the Royal Society.

Longitude

In 1714, he was instrumental in the passing of theLongitude Act

The Longitude Act 1714 was an Act of Parliament of Great Britain passed in July 1714 at the end of the reign of Anne, Queen of Great Britain, Queen Anne. It established the Board of Longitude and offered monetary Bounty (reward), rewards (Longitud ...

, which established the Board of Longitude

The Commissioners for the Discovery of the Longitude at Sea, or more popularly Board of Longitude, was a British government body formed in 1714 to administer a scheme of prizes intended to encourage innovators to solve the problem of finding lon ...

. In collaboration with Humphrey Ditton he published ''A New Method for Discovering the Longitude, both at Sea and Land'', which was widely referenced and discussed. For the next forty years he continued to propose a range of methods to solve the longitude reward, which earned him widespread ridicule, particularly from the group of writers known as the Scriblerians

The Scriblerus Club was an informal association of authors, based in London, that came together in the early 18th century. They were prominent figures in the Augustan Age of English letters. The nucleus of the club included the satirists Jonathan ...

. In one proposal for using magnetic dip to find longitude he produced one of the first isoclinic In mathematics, specifically group theory, isoclinism is an equivalence relation on groups which generalizes isomorphism. Isoclinism was introduced by to help classify and understand p-groups, although it is applicable to all groups. Isoclinism al ...

maps of southern England in 1719 and 1721. In 1734, he proposed using the eclipses of Jupiter's satellites.

Broader natural philosophy

Whiston's '' A New Theory of the Earth from its Original to the Consummation of All Things'' (1696) was an articulation of creationism andflood geology

Flood geology (also creation geology or diluvial geology) is a pseudoscientific attempt to interpret and reconcile geological features of the Earth in accordance with a literal belief in the global flood described in Genesis 6–8. In the ea ...

. It held that the global flood

A flood myth or a deluge myth is a myth in which a great flood, usually sent by a deity or deities, destroys civilization, often in an act of divine retribution. Parallels are often drawn between the flood waters of these myths and the primae ...

of Noah had been caused by a comet

A comet is an icy, small Solar System body that, when passing close to the Sun, warms and begins to release gases, a process that is called outgassing. This produces a visible atmosphere or coma, and sometimes also a tail. These phenomena ...

. The work obtained the praise of John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism ...

, who classed the author among those who, if not adding much to our knowledge, "At least bring some new things to our thoughts." He was an early advocate, along with Edmond Halley

Edmond (or Edmund) Halley (; – ) was an English astronomer, mathematician and physicist. He was the second Astronomer Royal in Britain, succeeding John Flamsteed in 1720.

From an observatory he constructed on Saint Helena in 1676–77, H ...

, of the periodicity of comets; he also held that comets were responsible for past catastrophes in Earth's history. In 1736, he caused widespread anxiety among London's citizens when he predicted the world would end on 16 October

Events Pre-1600

* 456 – Ricimer defeats Avitus at Piacenza and becomes master of the Western Roman Empire.

* 690 – Empress Wu Zetian ascends to the throne of the Tang dynasty and proclaims herself ruler of the Chinese Empire.

* 91 ...

that year because a comet would hit the earth. William Wake

William Wake (26 January 165724 January 1737) was a priest in the Church of England and Archbishop of Canterbury from 1716 until his death in 1737.

Life

Wake was born in Blandford Forum, Dorset, and educated at Christ Church, Oxford. He took ...

as Archbishop of Canterbury officially denied this prediction to calm the public.

There was no consensus within the Newtonians as to how far mechanical causes could be held responsible for key events of sacred history: John Keill

John Keill FRS (1 December 1671 – 31 August 1721) was a Scottish mathematician, natural philosopher, and cryptographer who was an important defender of Isaac Newton.

Biography

Keill was born in Edinburgh, Scotland on 1 December 1671. His f ...

was at the opposite extreme to Whiston in minimising such causes. As a natural philosopher, Whiston's speculations respected no boundary with his theological views. He saw the creation of man as an intervention in the natural order. He picked up on Arthur Ashley Sykes's advice to Samuel Clarke to omit an eclipse and earthquake mentioned by Phlegon of Tralles from future editions of Clarke's Boyle lectures, these events being possibly synchronous with Christ's crucifixion

The crucifixion and death of Jesus occurred in 1st-century Judea, most likely in AD 30 or AD 33. It is described in the four canonical gospels, referred to in the New Testament epistles, attested to by other ancient sources, and consider ...

. Whiston published ''The Testimony of Phlegon Vindicated'' in 1732.

Views

The series of Moyer Lectures often made Whiston's unorthodox views a particular target. Whiston held that '' Song of Solomon'' wasapocrypha

Apocrypha are works, usually written, of unknown authorship or of doubtful origin. The word ''apocryphal'' (ἀπόκρυφος) was first applied to writings which were kept secret because they were the vehicles of esoteric knowledge considered ...

l and that the ''Book of Baruch

The Book of Baruch is a deuterocanonical book of the Bible, used in most Christian traditions, such as Catholic and Orthodox churches. In Judaism and Protestant Christianity, it is considered not to be part of the canon, with the Protestant B ...

'' was not. He modified the biblical Ussher chronology

The Ussher chronology is a 17th-century chronology of the history of the world formulated from a literal reading of the Old Testament by James Ussher, the Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of All Ireland. The chronology is sometimes associated ...

, setting the Creation

Creation may refer to:

Religion

*''Creatio ex nihilo'', the concept that matter was created by God out of nothing

* Creation myth, a religious story of the origin of the world and how people first came to inhabit it

* Creationism, the belief tha ...

at 4010 BCE. He challenged Newton's system of ''The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended

''The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended'' is a work of historical chronology written by Sir Isaac Newton, first published posthumously in 1728. Since then it has been republished. The work, some 87,000 words, represents one of Newton's for ...

'' (1728). Westfall absolves Whiston of the charge that he pushed for the posthumous publication of the ''Chronology'' just to attack it, commenting that the heirs were in any case looking to publish manuscripts of Newton, who died in 1727.

Whiston's advocacy of clerical monogamy

Monogamy ( ) is a form of dyadic relationship in which an individual has only one partner during their lifetime. Alternately, only one partner at any one time (serial monogamy) — as compared to the various forms of non-monogamy (e.g., polyga ...

is referenced in Oliver Goldsmith's novel ''The Vicar of Wakefield

''The Vicar of Wakefield'', subtitled ''A Tale, Supposed to be written by Himself'', is a novel by Anglo-Irish writer Oliver Goldsmith (1728–1774). It was written from 1761 to 1762 and published in 1766. It was one of the most popular and wid ...

''. His last "famous discovery, or rather revival of Dr Giles Fletcher, the Elder

Giles Fletcher, the Elder (c. 1548 – 1611) was an English poet and diplomat, member of the English Parliament.

Giles Fletcher was the son of Richard Fletcher, vicar of Bishop's Stortford.

Fletcher was born in Watford, Hertfordshire. He s ...

's," which he mentions in his autobiography, was the identification of the Tatars

The Tatars ()Tatar

in the Collins English Dictionary is an umbrella term for different

with the in the Collins English Dictionary is an umbrella term for different

lost tribes of Israel

The ten lost tribes were the ten of the Twelve Tribes of Israel that were said to have been exiled from the Kingdom of Israel after its conquest by the Neo-Assyrian Empire BCE. These are the tribes of Reuben, Simeon, Dan, Naphtali, Gad, As ...

.

Personal life

Whiston married Ruth, daughter of George Antrobus, his headmaster at Tamworth school. He had a happy family life and died inLyndon

Lyndon may refer to:

Places

* Lyndon, Alberta, Canada

* Lyndon, Rutland, East Midlands, England

* Lyndon, Solihull, West Midlands, England

United States

* Lyndon, Illinois

* Lyndon, Kansas

* Lyndon, Kentucky

* Lyndon, New York

* Lyndon, Ohio

* ...

Hall, Rutland, at the home of his son-in-law, Samuel Barker, on 22 August 1752. He was survived by his children Sarah, William, George, and John.

Works

Whiston's later life was spent in continual controversy:

Whiston's later life was spent in continual controversy: theological

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the s ...

, mathematical, chronological

Chronology (from Latin ''chronologia'', from Ancient Greek , ''chrónos'', "time"; and , '' -logia'') is the science of arranging events in their order of occurrence in time. Consider, for example, the use of a timeline or sequence of events. ...

, and miscellaneous. He vindicated his estimate of the ''Apostolical Constitutions'' and the Arian views he had derived from them in his ''Primitive Christianity Revived'' (5 vols., 1711–1712). In 1713 he produced a reformed liturgy. His ''Life of Samuel Clarke'' appeared in 1730.

In 1727 he published a two volume work called ''Authentik Record belonging to the Old and New Testament''. This was a collection of translations and essays on various deuterocanonical books, pseudepigrapha and other essays with a translation if relevant.

His translation of the works of Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; grc-gre, Ἰώσηπος, ; 37 – 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for '' The Jewish War'', who was born in Jerusalem—then part of Roman Judea—to a father of priestly ...

(1737), with notes and dissertations, is often reprinted. The text on which Whiston's translation of Josephus is based is, reputedly, one which had many errors in transcription. In 1745 he published his ''Primitive New Testament'' (on the basis of Codex Bezae

The Codex Bezae Cantabrigiensis, designated by siglum D or 05 (in the Gregory-Aland numbering of New Testament manuscripts), δ 5 (in the von Soden of New Testament manuscript), is a codex of the New Testament dating from the 5th century writ ...

and Codex Claromontanus).

Whiston left memoirs (3 vols., 1749–1750). These do not contain the account of the proceedings taken against him at Cambridge for his antitrinitarianism

Nontrinitarianism is a form of Christianity that rejects the mainstream Christian doctrine of the Trinity—the belief that God is three distinct hypostases or persons who are coeternal, coequal, and indivisibly united in one being, or essence ...

, which was published separately at the time.

Editions

* *See also

*Noah's Flood

The Genesis flood narrative (chapters 6–9 of the Book of Genesis) is the Hebrew version of the universal flood myth. It tells of God's decision to return the universe to its pre- creation state of watery chaos and remake it through the micro ...

* Catastrophism

* Biblical prophecy

Bible prophecy or biblical prophecy comprises the passages of the Bible that are claimed to reflect communications from God to humans through prophets. Jews and Christians usually consider the biblical prophets to have received revelations from G ...

* Dorsa Whiston, named after him

References

Further reading

* * *External links

*Biography of William Whiston

at the LucasianChair.org, the homepage of the

Lucasian Chair of Mathematics

The Lucasian Chair of Mathematics () is a mathematics professorship in the University of Cambridge, England; its holder is known as the Lucasian Professor. The post was founded in 1663 by Henry Lucas, who was Cambridge University's Member of Pa ...

at Cambridge University

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209 and granted a royal charter by Henry III of England, Henry III in 1231, Cambridge is the world' ...

Bibliography for William Whiston

at the LucasianChair.org the homepage of the Lucasian Chair of Mathematics at Cambridge University

* * * *

"Account of Newton"

''Collection of Authentick Records'' (1728), pp. 1070–1082

"The Works of Flavius Josephus"

translated by William Whiston

by

Immanuel Velikovsky

Immanuel Velikovsky (; rus, Иммануи́л Велико́вский, p=ɪmənʊˈil vʲɪlʲɪˈkofskʲɪj; 17 November 1979) was a Jewish, Russian-American psychoanalyst, writer, and catastrophist. He is the author of several books offering ...

"Whiston's Flood"

"William Whiston, The Universal Deluge, and a Terrible Specracle" by Roomet Jakapi

''Collection of Authentick Records'' by Whiston at the Newton Project

Collection of William Whiston portraits

at England's National Portrait Gallery

Primitive New Testament

William Whiston | Portraits From the Past

(1696) – full digital facsimile at Linda Hall Library {{DEFAULTSORT:Whiston, William 1667 births 1752 deaths 17th-century apocalypticists 17th-century English mathematicians 18th-century apocalypticists 18th-century English mathematicians Alumni of Clare College, Cambridge Catastrophism Chronologists English Baptists Lucasian Professors of Mathematics People from Hinckley and Bosworth (district) Post-Reformation Arian Christians