William Web Ellis on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

William Webb Ellis (24 November 1806 – 24 January 1872) was an English

After his father was killed during the

After his father was killed during the

The sole source of the story of Webb Ellis picking up the ball originates with one

The sole source of the story of Webb Ellis picking up the ball originates with one

COMMEMORATES THE EXPLOIT OF

WILLIAM WEBB ELLIS

WHO WITH A FINE DISREGARD FOR THE RULES OF FOOTBALL

AS PLAYED IN HIS TIME

FIRST TOOK THE BALL IN HIS ARMS AND RAN WITH IT

THUS ORIGINATING THE DISTINCTIVE FEATURE OF

THE RUGBY GAME

A.D. 1823

Richard Lindon inventor of the "Oval" ball, the rubber bladder and the Brass Hand pump

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ellis, William Webb 1806 births 1872 deaths English people of Welsh descent Alumni of Brasenose College, Oxford 19th-century English Anglican priests English cricketers English cricketers of 1826 to 1863 English expatriates in France History of rugby league History of rugby union World Rugby Hall of Fame inductees Oxford University cricketers People educated at Rugby School People from Rugby, Warwickshire People from Salford Rugby football

Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

clergyman who, by tradition, has been credited as the inventor of rugby football

Rugby football is the collective name for the team sports of rugby union and rugby league.

Canadian football and, to a lesser extent, American football were once considered forms of rugby football, but are seldom now referred to as such. The ...

while a pupil at Rugby School

Rugby School is a public school (English independent boarding school for pupils aged 13–18) in Rugby, Warwickshire, England.

Founded in 1567 as a free grammar school for local boys, it is one of the oldest independent schools in Britain. Up ...

. According to legend, Webb Ellis picked up the ball and ran with it during a school football match in 1823, thus creating the "rugby" style of play. Although the story has become firmly entrenched in the sport's folklore, it is not supported by substantive evidence, and is discounted by most rugby historians as an origin myth

An origin myth is a myth that describes the origin of some feature of the natural or social world. One type of origin myth is the creation or cosmogonic myth, a story that describes the creation of the world. However, many cultures have stor ...

.

The Webb Ellis Cup

The Webb Ellis Cup is the trophy awarded to the winner of the men's Rugby World Cup, the premier competition in men's international rugby union. The Cup is named after William Webb Ellis, who is often credited as being the inventor of rugby footba ...

is presented to the winners of the Rugby World Cup

The Rugby World Cup is a men's rugby union tournament contested every four years between the top international teams. The tournament is administered by World Rugby, the sport's international governing body. The winners are awarded the Webb E ...

.

Biography

William Webb Ellis was born inSalford

Salford () is a city and the largest settlement in the City of Salford metropolitan borough in Greater Manchester, England. In 2011, Salford had a population of 103,886. It is also the second and only other city in the metropolitan county afte ...

, Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated Lancs) is the name of a historic county, ceremonial county, and non-metropolitan county in North West England. The boundaries of these three areas differ significantly.

The non-metropolitan county of Lancashi ...

, the younger of three sons of James Ellis, a cornet in the 7th Dragoon Guards

The 7th (The Princess Royal's) Dragoon Guards was a cavalry regiment in the British Army, first raised in 1688 as Lord Cavendish's Regiment of Horse. It was renamed as the 7th (The Princess Royal's) Dragoon Guards for Princess Charlotte in 1788. ...

. The eldest son, James, died aged three and the second son, Thomas, of Dunchurch

Dunchurch is a large village and civil parish on the south-western outskirts of Rugby in Warwickshire, England, approximately southwest of central Rugby. The civil parish which also includes the nearby hamlet of Toft, had a population of 4,12 ...

, Warwickshire

Warwickshire (; abbreviated Warks) is a county in the West Midlands region of England. The county town is Warwick, and the largest town is Nuneaton. The county is famous for being the birthplace of William Shakespeare at Stratford-upon-Avon an ...

, became a surgeon. Third son William was made a Lieutenant of the 3rd Dragoon Guards

The 3rd (Prince of Wales's) Dragoon Guards was a cavalry regiment in the British Army, first raised in 1685 as the Earl of Plymouth's Regiment of Horse. It was renamed as the 3rd Regiment of Dragoon Guards in 1751 and the 3rd (Prince of Wales's) ...

in 1809, joining them in Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

,Notices of the Ellises of England, Scotland and Ireland, from the Conquest to the present time, William Smith Ellis, 1866, pg 175 William's father James was married for a second time in Exeter

Exeter () is a city in Devon, South West England. It is situated on the River Exe, approximately northeast of Plymouth and southwest of Bristol.

In Roman Britain, Exeter was established as the base of Legio II Augusta under the personal comm ...

in 1804 to Ann, daughter of William Webb, a surgeon, of Alton, Hampshire

Alton ( ) is a market town and civil parish in the East Hampshire district of Hampshire, England, near the source of the River Wey. It had a population of 17,816 at the 2011 census.

Alton was recorded in the Domesday Survey of 1086 as ''Aoltone'' ...

. His paternal grandfather was from Pontyclun

Pontyclun (or Pont-y-clun) is a village and community located in the county borough of Rhondda Cynon Taf, Wales. Like the surrounding towns, it has seen a sharp increase in its population in the last ten years as people migrate south from the So ...

in South Wales

South Wales ( cy, De Cymru) is a loosely defined region of Wales bordered by England to the east and mid Wales to the north. Generally considered to include the historic counties of Glamorgan and Monmouthshire, south Wales extends westwards ...

, a descendant of the Ellis family of Kiddal Hall, just off the A64 near Potterton

Potterton is a village north of Aberdeen, Scotland, in Aberdeenshire, west of Balmedie. Population in 1991 was 1159, falling by 2001 to 886.

References

Villages in Aberdeenshire

{{Aberdeenshire-geo-stub ...

, West Riding of Yorkshire

The West Riding of Yorkshire is one of three historic subdivisions of Yorkshire, England. From 1889 to 1974 the administrative county County of York, West Riding (the area under the control of West Riding County Council), abbreviated County ...

.

Peninsular War

The Peninsular War (1807–1814) was the military conflict fought in the Iberian Peninsula by Spain, Portugal, and the United Kingdom against the invading and occupying forces of the First French Empire during the Napoleonic Wars. In Spain ...

in a cavalry action near Albuera on 1 July 1812, Mrs Ellis, in receipt of an allowance of £30 from His Majesty's Royal Bounty in recognition of her husband's service, decided to move to Rugby, Warwickshire

Rugby is a market town in eastern Warwickshire, England, close to the River Avon. In the 2021 census its population was 78,125, making it the second-largest town in Warwickshire. It is the main settlement within the larger Borough of Rugby whi ...

, so that William and his elder brother, Thomas, would receive an education at Rugby School

Rugby School is a public school (English independent boarding school for pupils aged 13–18) in Rugby, Warwickshire, England.

Founded in 1567 as a free grammar school for local boys, it is one of the oldest independent schools in Britain. Up ...

with no cost as a local foundationer (i.e. a pupil living within a radius of 10 miles of the Rugby Clock Tower). He attended the school in Town House from 1816 to 1825 and was recorded as being a good scholar and cricket

Cricket is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams of eleven players on a field at the centre of which is a pitch with a wicket at each end, each comprising two bails balanced on three stumps. The batting side scores runs by striki ...

er, although it was noted that he was "rather inclined to take unfair advantage at cricket". The incident in which William Webb Ellis supposedly caught the ball in his arms during a football match (which was allowed) and ran with it (which was not) is supposed to have happened in the latter half of 1823.

After leaving Rugby in 1826, he went to Brasenose College, Oxford

Brasenose College (BNC) is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. It began as Brasenose Hall in the 13th century, before being founded as a college in 1509. The library and chapel were added in the mi ...

, aged 20. He played cricket

Cricket is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams of eleven players on a field at the centre of which is a pitch with a wicket at each end, each comprising two bails balanced on three stumps. The batting side scores runs by striki ...

for his college, and for Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

against Cambridge University

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

in a first-class match in 1827. He graduated with a B.A. in 1829 and received his M.A. in 1831. He entered the Church

Church may refer to:

Religion

* Church (building), a building for Christian religious activities

* Church (congregation), a local congregation of a Christian denomination

* Church service, a formalized period of Christian communal worship

* Chris ...

and became chaplain of St George's Chapel, Albemarle Street

Albemarle Street is a street in Mayfair in central London, off Piccadilly. It has historic associations with Lord Byron, whose publisher John Murray was based here, and Oscar Wilde, a member of the Albemarle Club, where an insult he received ...

, London (closed c.1909), and then rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

of St Clement Danes

St Clement Danes is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London. It is situated outside the Royal Courts of Justice on the Strand. Although the first church on the site was reputedly founded in the 9th century by the Danes, the current ...

in the Strand

Strand may refer to:

Topography

*The flat area of land bordering a body of water, a:

** Beach

** Shoreline

*Strand swamp, a type of swamp habitat in Florida

Places Africa

*Strand, Western Cape, a seaside town in South Africa

* Strand Street, ...

. He became well known as a low church evangelical

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide Interdenominationalism, interdenominational movement within Protestantism, Protestant Christianity that affirms the centrality of being "bor ...

clergyman. In 1855, he became rector of Magdalen Laver

Magdalen Laver is a village and a civil parish in the Epping Forest district, in the county of Essex, England. Magdalen Laver is east of Harlow and of close proximity to the M11 motorway. Magdalen Laver has a village hall and a church called S ...

in Essex

Essex () is a county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the River Thames to the south, and G ...

. A picture of him (the only known portrait) appeared in the ''Illustrated London News

''The Illustrated London News'' appeared first on Saturday 14 May 1842, as the world's first illustrated weekly news magazine. Founded by Herbert Ingram, it appeared weekly until 1971, then less frequently thereafter, and ceased publication in ...

'' in 1854, after he gave a particularly stirring sermon on the subject of the Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the de ...

.

He never married and died in the south of France in 1872, leaving an estate of £9,000, mostly to various charities. His grave in ''le cimetière du vieux château'' at Menton

Menton (; , written ''Menton'' in classical norm or ''Mentan'' in Mistralian norm; it, Mentone ) is a commune in the Alpes-Maritimes department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region on the French Riviera, close to the Italian border.

Me ...

in Alpes Maritimes

Alpes-Maritimes (; oc, Aups Maritims; it, Alpi Marittime, "Maritime Alps") is a department of France located in the country's southeast corner, on the Italian border and Mediterranean coast. Part of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, it ...

was rediscovered by Ross McWhirter

Alan Ross McWhirter (12 August 1925 – 27 November 1975) was, with his twin brother, Norris, the cofounder of the 1955 ''Guinness Book of Records'' (known since 2000 as ''Guinness World Records'') and a contributor to the television programm ...

in 1958, was renovated by the Riviera Hash House Harriers in 2003 and is now maintained by the French Rugby Federation

The French Rugby Federation (french: Fédération Française de Rugby (''FFR'')) is the governing body for rugby union in France. It is responsible for the France national rugby union team, French national team and the National Rugby League (Franc ...

.

Legend

Origin

The sole source of the story of Webb Ellis picking up the ball originates with one

The sole source of the story of Webb Ellis picking up the ball originates with one Matthew Bloxam

Matthew Holbeche Bloxam (12 May 1805 – 24 April 1888), a native of Rugby, Warwickshire, England, was a Warwickshire antiquary and amateur archeologist, author of a popular guide to Gothic architecture. He was the original source of the legend o ...

, a local antiquarian and former pupil of Rugby. On 10 October 1876, he wrote to ''The Meteor'', the Rugby School magazine, that he had learnt from an unnamed source that the change from a kicking game to a handling game had "...originated with a town boy or foundationer of the name of Ellis, Webb Ellis".

On 22 December 1880, in another letter to ''The Meteor'', Bloxam elaborates on the story:

Bloxam's first account differed from his second one four years later. In his first letter, in 1876, Bloxham claimed that Webb Ellis committed the act in 1824, a time by which Webb Ellis had left Rugby. In his second letter, in 1880, Bloxham put the year as 1823.

1895 investigation

The claim that Webb Ellis invented the game did not surface until four years after his death, and doubts have been raised about the story since 1895, when the Old Rugbeian Society first investigated it. The sub-committee conducting the investigation was "unable to procure any first hand evidence of the occurrence". Among those giving evidence, Thomas Harris and his brother John, who had left Rugby in 1828 and 1832 respectively (i.e. after the alleged Webb Ellis incident) recalled that handling of the ball was strictly forbidden. Thomas Harris, who requested that he "not equote as an authority", testified that Webb Ellis had been known as someone to take an "unfair advantage at football". John Harris, who would have been aged 10 years at the time of the alleged incident, did not claim to have been a witness to it. Additionally, he stated that he had not heard the story of Webb Ellis's creation of the game.Thomas Hughes

Thomas Hughes (20 October 182222 March 1896) was an English lawyer, judge, politician and author. He is most famous for his novel ''Tom Brown's School Days'' (1857), a semi-autobiographical work set at Rugby School, which Hughes had attended. ...

(author of ''Tom Brown's Schooldays

''Tom Brown's School Days'' (sometimes written ''Tom Brown's Schooldays'', also published under the titles ''Tom Brown at Rugby'', ''School Days at Rugby'', and ''Tom Brown's School Days at Rugby'') is an 1857 novel by Thomas Hughes. The stor ...

'') was asked to comment on the game as played when he attended the school (1834–1842). He is quoted as saying "In my first year, 1834, running with the ball to get a try by touching down within goal was not absolutely forbidden, but a jury of Rugby boys of that day would almost certainly have found a verdict of 'justifiable homicide' if a boy had been killed in running in."

It has been suggested by Dunning and Sheard (2005) that it was no coincidence that this investigation was conducted in 1895, at a time when divisions within the sport led to the schism

A schism ( , , or, less commonly, ) is a division between people, usually belonging to an organization, movement, or religious denomination. The word is most frequently applied to a split in what had previously been a single religious body, suc ...

: the split into the sports of rugby league

Rugby league football, commonly known as just rugby league and sometimes football, footy, rugby or league, is a full-contact sport played by two teams of thirteen players on a rectangular field measuring 68 metres (75 yards) wide and 112 ...

and rugby union

Rugby union, commonly known simply as rugby, is a close-contact team sport that originated at Rugby School in the first half of the 19th century. One of the two codes of rugby football, it is based on running with the ball in hand. In its m ...

. Dunning and Sheard suggest that the endorsement of a "reductionist" origin myth

An origin myth is a myth that describes the origin of some feature of the natural or social world. One type of origin myth is the creation or cosmogonic myth, a story that describes the creation of the world. However, many cultures have stor ...

by the Rugbeians was an attempt to assert their school's position and authority over a sport that they were losing control of.

Jem Mackie

An article by Gordon Rayner in ''The Sunday Telegraph

''The Sunday Telegraph'' is a British broadsheet newspaper, founded in February 1961 and published by the Telegraph Media Group, a division of Press Holdings.

It is the sister paper of ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', kn ...

'' about the origin of Rugby football says that Thomas Hughes told the 1895 investigation that in 1838–1839 a Rugby School boy called Jem Mackie "was the first great runner-in", and that later (in or before 1842) Jem Mackie was expelled from Rugby School for an unspecified incident; in 1845 boys at the school first wrote down an agreed set of rules for the version of football played at Rugby School, which is now rugby football

Rugby football is the collective name for the team sports of rugby union and rugby league.

Canadian football and, to a lesser extent, American football were once considered forms of rugby football, but are seldom now referred to as such. The ...

. Gordon Rayner says that the reason for Jem Mackie's expulsion may have damaged Mackie's reputation so much that Bloxam transferred Mackie's part in inventing Rugby football to Webb Ellis, and that a big donation by Bloxam to Rugby School's library may have influenced school official acceptance of this Webb Ellis version.

Another theory is that Mackie's role may have been disregarded because the committee was seeking to prove Rugby School had invented the game, and thus may have preferred the earliest possible date. England Rugby

The England national rugby union team represents England in men's international rugby union. They compete in the annual Six Nations Championship with France, Ireland, Italy, Scotland and Wales. England have won the championship on 29 occasions ...

says that William Webb Ellis's action (if it happened) did not lead to any immediate change in the rules but may well have inspired later imitators, though not Mackie, as Thomas Hughes said the Webb Ellis story had not survived into his own time (1834, which was before Mackie popularised running-in during 1838/39).

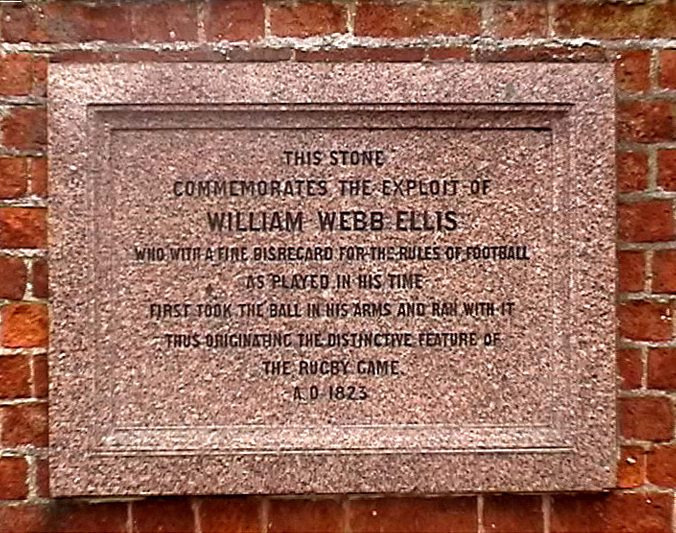

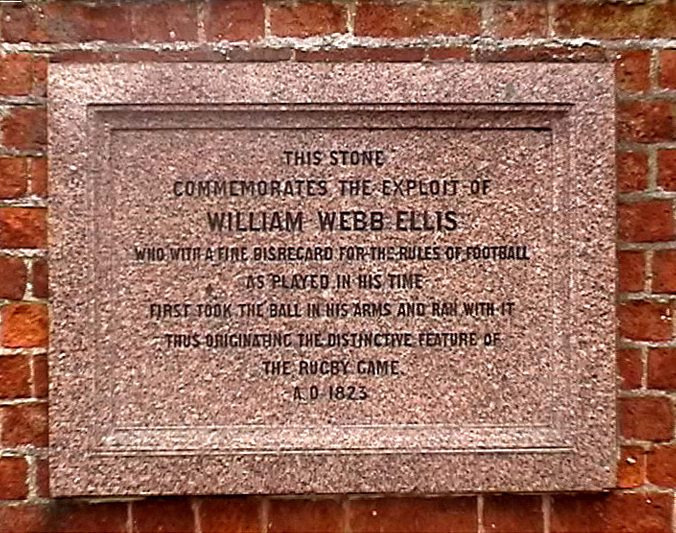

Plaque

A plaque, erected in 1895, at Rugby School bears the inscription: THIS STONECOMMEMORATES THE EXPLOIT OF

WILLIAM WEBB ELLIS

WHO WITH A FINE DISREGARD FOR THE RULES OF FOOTBALL

AS PLAYED IN HIS TIME

FIRST TOOK THE BALL IN HIS ARMS AND RAN WITH IT

THUS ORIGINATING THE DISTINCTIVE FEATURE OF

THE RUGBY GAME

A.D. 1823

See also

*Abner Doubleday

Abner Doubleday (June 26, 1819 – January 26, 1893) was a career United States Army officer and Union major general in the American Civil War. He fired the first shot in defense of Fort Sumter, the opening battle of the war, and had a pi ...

, sometimes apocryphally credited with inventing baseball

* Tom Wills

Thomas Wentworth Wills (19 August 1835 – 2 May 1880) was an Australian sportsman who is credited with being Australia's first cricketer of significance and a founder of Australian rules football. Born in the British penal colony of New ...

, attended Rugby School and pioneered Australian rules football

Australian football, also called Australian rules football or Aussie rules, or more simply football or footy, is a contact sport played between two teams of 18 players on an oval field, often a modified cricket ground. Points are scored by k ...

References

General

* * *External links

*Richard Lindon inventor of the "Oval" ball, the rubber bladder and the Brass Hand pump

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ellis, William Webb 1806 births 1872 deaths English people of Welsh descent Alumni of Brasenose College, Oxford 19th-century English Anglican priests English cricketers English cricketers of 1826 to 1863 English expatriates in France History of rugby league History of rugby union World Rugby Hall of Fame inductees Oxford University cricketers People educated at Rugby School People from Rugby, Warwickshire People from Salford Rugby football