William Spence on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

William Guthrie Spence (7 August 1846 – 13 December 1926), was an Australian

The defeat of the strikes of 1891–1894 led Spence and other labour leaders to move into politics. Spence supported the formation of the Progressive Political League, an early labour party, in Victoria in 1891 and he was narrowly beaten at a by-election in 1892 for the seat of Dundas in the

The defeat of the strikes of 1891–1894 led Spence and other labour leaders to move into politics. Spence supported the formation of the Progressive Political League, an early labour party, in Victoria in 1891 and he was narrowly beaten at a by-election in 1892 for the seat of Dundas in the

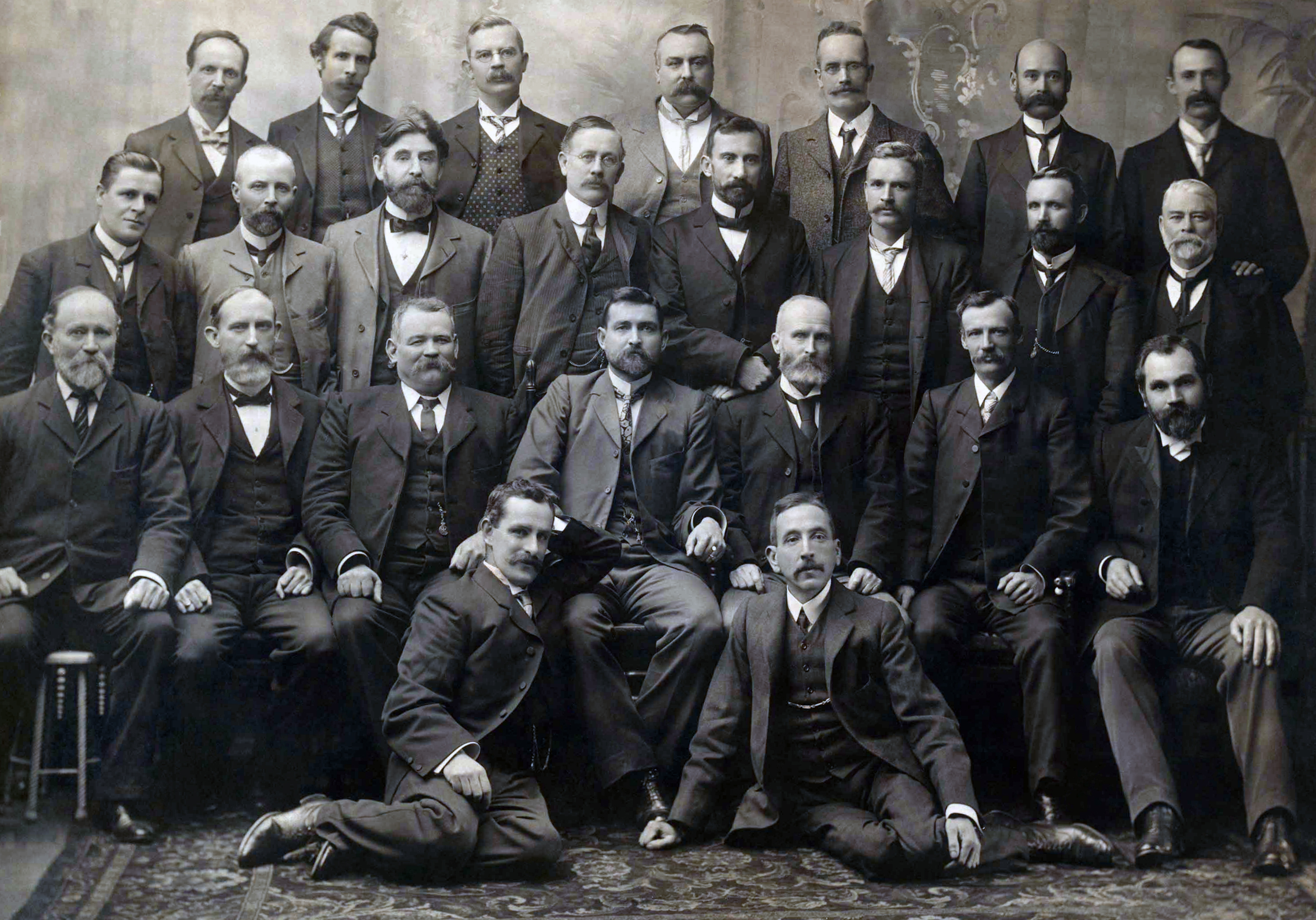

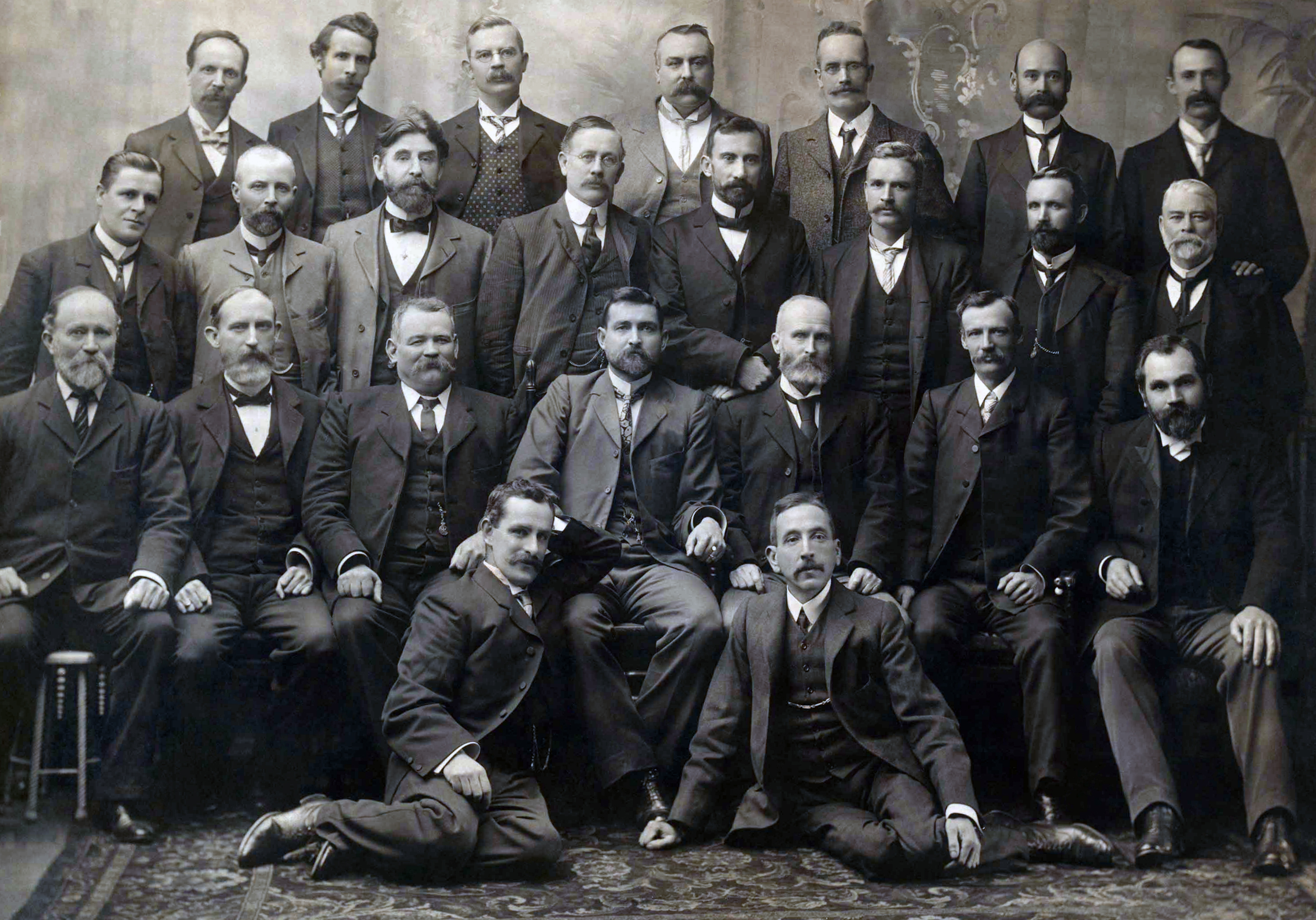

Australian Workers' Union memorial to Spence

{{DEFAULTSORT:Spence, William Guthrie Members of the Australian House of Representatives for Darling Members of the Australian House of Representatives for Darwin Members of the Australian House of Representatives Members of the Cabinet of Australia Members of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly Australian Labor Party members of the Parliament of Australia Australian trade unionists People from Orkney People from Victoria (Australia) Scottish emigrants to colonial Australia 1846 births 1926 deaths National Labor Party members of the Parliament of Australia Nationalist Party of Australia members of the Parliament of Australia 20th-century Australian politicians

trade union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ( ...

leader and politician, played a leading role in the formation of both Australia's largest union, the Australian Workers' Union

The Australian Workers' Union (AWU) is one of Australia's largest and oldest trade unions. It traces its origins to unions founded in the pastoral and mining industries in the 1880s and currently has approximately 80,000 members. It has exerci ...

, and the Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party (ALP), also simply known as Labor, is the major centre-left political party in Australia, one of two major parties in Australian politics, along with the centre-right Liberal Party of Australia. The party forms the f ...

.

Early life

Spence was born on the island ofEday

Eday (, sco, Aidee) is one of the islands of Orkney, which are located to the north of the Scottish mainland. One of the North Isles, Eday is about from the Orkney Mainland. With an area of , it is the ninth-largest island of the archipelago. ...

in the Orkney Islands

Orkney (; sco, Orkney; on, Orkneyjar; nrn, Orknøjar), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago in the Northern Isles of Scotland, situated off the north coast of the island of Great Britain. Orkney is 10 miles (16 km) north ...

, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

and migrated to Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

with his family as age six. He had no formal education and worked as a farm labourer in the Wimmera

The Wimmera is a region of the Australian state of Victoria. The district is located within parts of the Loddon Mallee and the Grampians regions; and covers the dryland farming area south of the range of Mallee scrub, east of the South Aust ...

district of Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Victoria (Australia), a state of the Commonwealth of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, provincial capital of British Columbia, Canada

* Victoria (mythology), Roman goddess of Victory

* Victoria, Seychelle ...

from the age of 13. Later he acquired a gold-mining licence and worked for various mining companies. In 1871 he married Ann Jane Savage.

In 1874, Spence was one of a number of militant mine-workers who formed the Amalgamated Miners' Association of Victoria, and he became the union's general secretary in 1882. He led the union into mergers with similar unions in the other Australian colonies

The states and territories are federated administrative divisions in Australia, ruled by regional governments that constitute the second level of governance between the federal government and local governments. States are self-governing ...

, forming the Amalgamated Miners' Association of Australasia. In 1886, he became the first president of the Australian Shearers' Union

The Australian Shearers' Union (also known as the Australasian Shearers Union, sometimes referred to as the Creswick Shearers' Union) was a significant but short-lived early trade union in Victoria and southern New South Wales. It was formed on 12 ...

; he also became president of its successor, the Amalgamated Shearers' Union of Australasia

The Amalgamated Shearers' Union of Australasia was an early Australian trade union. It was formed in January 1887 with the amalgamation of the Wagga Shearers Union and Bourke Shearers Union in New South Wales with the Victorian-based Australian ...

in 1887, and by 1890 most shearers in South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories ...

, Victoria and New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

had joined the union and 85% of the shearing sheds were open to union members only.

Around 1890, Spence became a strong proponent of Georgism

Georgism, also called in modern times Geoism, and known historically as the single tax movement, is an economic ideology holding that, although people should own the value they produce themselves, the economic rent derived from land—including ...

. The Georgist 'Single Tax' proposal was at the time incredibly popular amongst Radical Liberals and the movement was highly influential in the political labour movement, the Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party (ALP), also simply known as Labor, is the major centre-left political party in Australia, one of two major parties in Australian politics, along with the centre-right Liberal Party of Australia. The party forms the f ...

being created through the joint efforts of Single Taxers, socialists and trade unionists.

Since the Australian economy was expanding rapidly at this time and there was an acute shortage of labour, the unions were in a strong bargaining position and were able to secure great improvements in the living standards of Australia's rural working class. But a depression which began in 1891 led to acute class conflict as the mine owners and graziers tried to cut wages to remain solvent in the face of falling commodity prices, which the unions resisted. In 1894 Spence led the amalgamation of the miners, shearers and other rural workers into the Australian Workers' Union

The Australian Workers' Union (AWU) is one of Australia's largest and oldest trade unions. It traces its origins to unions founded in the pastoral and mining industries in the 1880s and currently has approximately 80,000 members. It has exerci ...

(AWU), Australia's largest and most powerful union. There were bitter strikes in the maritime and pastoral industries, in which Spence played a leading role, although he was generally a force for moderation in the labour movement. He was the AWU's secretary from 1894 to 1898 and president from 1898 to 1917.

Political career

The defeat of the strikes of 1891–1894 led Spence and other labour leaders to move into politics. Spence supported the formation of the Progressive Political League, an early labour party, in Victoria in 1891 and he was narrowly beaten at a by-election in 1892 for the seat of Dundas in the

The defeat of the strikes of 1891–1894 led Spence and other labour leaders to move into politics. Spence supported the formation of the Progressive Political League, an early labour party, in Victoria in 1891 and he was narrowly beaten at a by-election in 1892 for the seat of Dundas in the Victorian Legislative Assembly

The Victorian Legislative Assembly is the lower house of the bicameral Parliament of Victoria in Australia; the upper house being the Victorian Legislative Council. Both houses sit at Parliament House in Spring Street, Melbourne.

The presiding ...

. In 1891, he supported the first election campaign by the Labour Party in New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

, which won a number of seats in the New South Wales Legislative Assembly

The New South Wales Legislative Assembly is the lower of the two houses of the Parliament of New South Wales, an Australian state. The upper house is the New South Wales Legislative Council. Both the Assembly and Council sit at Parliament Ho ...

. In 1898, Spence he became MP for Cobar

Cobar is a town in central western New South Wales, Australia whose economy is based mainly upon base metals and gold mining. The town is by road northwest of the state capital, Sydney. It is at the crossroads of the Kidman Way and Barrier H ...

in western New South Wales. He remained president of the AWU, making him one of the most powerful men in New South Wales politics. He described himself as "an evolutionary, not a revolutionary, socialist."

Unlike many in the labour movement, Spence supported the federation

A federation (also known as a federal state) is a political entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a central federal government (federalism). In a federation, the self-governin ...

of the Australian colonies, and in 1901 he was elected to the first Australian House of Representatives

The House of Representatives is the lower house of the bicameral Parliament of Australia, the upper house being the Senate. Its composition and powers are established in Chapter I of the Constitution of Australia.

The term of members of the ...

as MP for the NSW Division of Darling

The Division of Darling was an Australian electoral division in the state of New South Wales. The division was proclaimed in 1900, and was one of the original 65 divisions to be contested at the first federal election. From 1901 until 1922 ...

. Like most of the older generation of labour leaders who were born in the United Kingdom, Spence was associated with the more conservative wing of the Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party (ALP), also simply known as Labor, is the major centre-left political party in Australia, one of two major parties in Australian politics, along with the centre-right Liberal Party of Australia. The party forms the f ...

, led by Billy Hughes

William Morris Hughes (25 September 1862 – 28 October 1952) was an Australian politician who served as the seventh prime minister of Australia, in office from 1915 to 1923. He is best known for leading the country during World War I, but ...

. He was not really suited to parliamentary life and did not hold office until he was appointed Postmaster-General

A Postmaster General, in Anglosphere countries, is the chief executive officer of the postal service of that country, a Ministry (government department), ministerial office responsible for overseeing all other postmasters. The practice of having ...

in the third Fisher Ministry

The Third Fisher ministry (Labor) was the 10th ministry of the Government of Australia. It was led by the country's 5th Prime Minister, Andrew Fisher. The Third Fisher ministry succeeded the Cook ministry, which dissolved on 17 September 191 ...

from September 1914 to October 1915. He was also appointed to the undemanding position of Vice-President of the Executive Council

The Vice-President of the Executive Council is the minister in the Government of Australia who acts as the presiding officer of meetings of the Federal Executive Council when the Governor-General is absent. The Vice-President of the Executiv ...

in the second Hughes Ministry from November 1916 to February 1917.

In 1916 Hughes decided to introduce conscription

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day un ...

to maintain Australia's contribution to the Allied forces in World War I. Most of the Labor Party bitterly opposed this, but Spence sided with Hughes. As a result, he was expelled from the party along with Hughes and the other conscriptionist MPs. He was also deposed as president of the AWU and shortly after was expelled from the union. At the 1917 federal election, although Hughes was easily returned to power, Spence lost his seat, mainly because the AWU organised the rural workers to oppose him. Shortly after he was returned to Parliament at a by-election for the Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

n seat of Darwin. He was one of only a small number of people who have represented more than one state or territory in the Parliament. In 1919, he ran for the Melbourne seat of Batman

Batman is a superhero appearing in American comic books published by DC Comics. The character was created by artist Bob Kane and writer Bill Finger, and debuted in Detective Comics 27, the 27th issue of the comic book ''Detective Comics'' on ...

, but was defeated.

Spence later took up farming at Terang

Terang is a town in the Western District of Victoria, Australia. The town is in the Shire of Corangamite and on the Princes Highway south west of the state's capital, Melbourne. At the , Terang had a population of 1,824. At the 2001 census, ...

, Victoria, and died of pulmonary oedema

Pulmonary edema, also known as pulmonary congestion, is excessive liquid accumulation in the tissue and air spaces (usually alveoli) of the lungs. It leads to impaired gas exchange and may cause hypoxemia and respiratory failure. It is due to ...

on 13 December 1926, aged 80. He was survived by his wife, four daughters and three of his five sons. His daughter Gwynetha had married publisher and politician Hector Lamond

Hector Lamond (31 October 1865 – 26 April 1947) was an Australian politician. He was a Nationalist Party member of the Australian House of Representatives from 1917 to 1922, representing the electorate of Illawarra.

Early life and career

La ...

in 1902.

Honours

In 1972, theCanberra

Canberra ( )

is the capital city of Australia. Founded following the federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's largest inland city and the eighth-largest city overall. The ci ...

suburb of Spence was named after him. In October 2003 the Australian Workers' Union named its Melbourne headquarters in Spence's honour.

References

Further reading

* *External links

Australian Workers' Union memorial to Spence

{{DEFAULTSORT:Spence, William Guthrie Members of the Australian House of Representatives for Darling Members of the Australian House of Representatives for Darwin Members of the Australian House of Representatives Members of the Cabinet of Australia Members of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly Australian Labor Party members of the Parliament of Australia Australian trade unionists People from Orkney People from Victoria (Australia) Scottish emigrants to colonial Australia 1846 births 1926 deaths National Labor Party members of the Parliament of Australia Nationalist Party of Australia members of the Parliament of Australia 20th-century Australian politicians