William Palmer (murderer) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

William Palmer (6 August 1824 – 14 June 1856), also known as the Rugeley Poisoner or the Prince of Poisoners, was an English doctor found guilty of murder in one of the most notorious cases of the 19th century.

John Parsons Cook, a sickly young man with an inherited fortune of £12,000, was a friend of Palmer. In November 1855, the pair attended the

John Parsons Cook, a sickly young man with an inherited fortune of £12,000, was a friend of Palmer. In November 1855, the pair attended the

Approximately 30,000 people were at Stafford prison on 14 June 1856 to see Palmer's

Approximately 30,000 people were at Stafford prison on 14 June 1856 to see Palmer's

Shee, Sir William (1804–1868)

, rev. Hugh Mooney, ''

Palmer,_William_[ _the_Rugeley_Poisoner

/nowiki>_(1824–1856).html" ;"title="/nowiki> the Rugeley Poisoner">Palmer, William [ the Rugeley Poisoner

/nowiki> (1824–1856)">/nowiki> the Rugeley Poisoner">Palmer, William [ the Rugeley Poisoner

/nowiki> (1824–1856), ''

williampalmer.co.ukWilliam Palmer

on the BBC

Staffordshire Past Track

– William Palmer * {{DEFAULTSORT:Palmer, William 1824 births 1855 murders in the United Kingdom 1856 deaths 19th-century English medical doctors 19th-century executions by England and Wales English people convicted of murder Executed people from Staffordshire Medical practitioners convicted of murdering their patients Murderers for life insurance money People convicted of murder by England and Wales People from Rugeley Poisoners Suspected serial killers

Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian e ...

called Palmer "the greatest villain

A villain (also known as a "black hat" or "bad guy"; the feminine form is villainess) is a stock character, whether based on a historical narrative or one of literary fiction. ''Random House Unabridged Dictionary'' defines such a character a ...

that ever stood in the Old Bailey

The Central Criminal Court of England and Wales, commonly referred to as the Old Bailey after the street on which it stands, is a criminal court building in central London, one of several that house the Crown Court of England and Wales. The s ...

".

Palmer was convicted for the 1855 murder of his friend John Cook, and was executed in public by hanging

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a noose or ligature around the neck.Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Hanging as method of execution is unknown, as method of suicide from 1325. The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' states that hanging i ...

the following year. He had poisoned Cook with strychnine

Strychnine (, , US chiefly ) is a highly toxic, colorless, bitter, crystalline alkaloid used as a pesticide, particularly for killing small vertebrates such as birds and rodents. Strychnine, when inhaled, swallowed, or absorbed through the eye ...

and was suspected of poisoning several other people including his brother and his mother-in-law, as well as four of his children who died of " convulsions" before their first birthdays. Palmer made large sums of money from the deaths of his wife and brother after collecting on life insurance

Life insurance (or life assurance, especially in the Commonwealth of Nations) is a contract between an insurance policy holder and an insurer or assurer, where the insurer promises to pay a designated beneficiary a sum of money upon the death ...

, and by defrauding

In law, fraud is intentional deception to secure unfair or unlawful gain, or to deprive a victim of a legal right. Fraud can violate civil law (e.g., a fraud victim may sue the fraud perpetrator to avoid the fraud or recover monetary compensa ...

his wealthy mother out of thousands of pounds, all of which he lost through gambling

Gambling (also known as betting or gaming) is the wagering of something of value ("the stakes") on a random event with the intent of winning something else of value, where instances of strategy are discounted. Gambling thus requires three el ...

on horses

The horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of ''Equus ferus''. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 million yea ...

.

Early life and suspected poisonings

William Palmer was born inRugeley

Rugeley ( ) is a market town and civil parish in the Cannock Chase District in Staffordshire, England. It lies on the north-eastern edge of Cannock Chase next to the River Trent; it is situated north of Lichfield, south-east of Stafford, nort ...

, Staffordshire

Staffordshire (; postal abbreviation Staffs.) is a landlocked county in the West Midlands region of England. It borders Cheshire to the northwest, Derbyshire and Leicestershire to the east, Warwickshire to the southeast, the West Midlands Cou ...

, the sixth of eight children of Sarah and Joseph Palmer. His father worked as a sawyer

*A sawyer (occupation) is someone who saws wood.

*Sawyer, a fallen tree stuck on the bottom of a river, where it constitutes a danger to boating.

Places in the United States

Communities

*Sawyer, Kansas

*Sawyer, Kentucky

* Sawyer, Michigan

* Saw ...

and died when William was aged 12, leaving Sarah with a legacy of £70,000.

As a seventeen-year-old, Palmer worked as an apprentice at a Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a popul ...

chemist, but was dismissed after three months following allegations that he stole money. He studied medicine in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

, and qualified as a physician

A physician (American English), medical practitioner (Commonwealth English), medical doctor, or simply doctor, is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through th ...

in August 1846. After returning to Staffordshire

Staffordshire (; postal abbreviation Staffs.) is a landlocked county in the West Midlands region of England. It borders Cheshire to the northwest, Derbyshire and Leicestershire to the east, Warwickshire to the southeast, the West Midlands Cou ...

later that year Palmer met plumber and glazier George Abley at the Lamb and Flag public house

A pub (short for public house) is a kind of drinking establishment which is licensed to serve alcoholic drinks for consumption on the premises. The term ''public house'' first appeared in the United Kingdom in late 17th century, and was ...

in Little Haywood

Little Haywood is a village in Staffordshire, England. For population details as taken at the United Kingdom Census 2011, 2011 census see under Colwich, Staffordshire, Colwich. It lies beside a main arterial highway, the A51 road, A51 (linking ...

, and challenged him to a drinking contest. Abley accepted, and an hour later was carried home, where he died in bed later that evening; nothing was ever proved, but locals noted that Palmer had an interest in Abley's attractive wife.

Palmer returned to his home town of Rugeley to practise as a doctor and, in St. Nicholas Church, Abbots Bromley

Abbots Bromley is a village and civil parish in the East Staffordshire district of Staffordshire and lies approximately east of Stafford, England. According to the University of Nottingham English Place-names project, the settlement name Abbots ...

, married Ann Thornton (born 1827; also known as Brookes as her mother was the mistress of a Colonel Brookes) on 7 October 1847. His new mother-in-law, also called Ann Thornton, had inherited a fortune of £8,000 after Colonel Brookes committed suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders), physical disorders (such as chronic fatigue syndrome), and s ...

in 1834. The elder Thornton died on 18 January 1849, two weeks after coming to stay with Palmer; she was known to have lent him money. An elderly Dr. Bamford recorded a verdict of apoplexy

Apoplexy () is rupture of an internal organ and the accompanying symptoms. The term formerly referred to what is now called a stroke. Nowadays, health care professionals do not use the term, but instead specify the anatomic location of the bleedi ...

. Palmer was disappointed with the inheritance he and his wife gained from the death, having expected it to be much greater.

Palmer became interested in horse racing

Horse racing is an equestrian performance sport, typically involving two or more horses ridden by jockeys (or sometimes driven without riders) over a set distance for competition. It is one of the most ancient of all sports, as its basic p ...

and borrowed money from Leonard Bladen, a man he met at the races. Bladen lent him £600, but died in agony at Palmer's house on 10 May 1850. Palmer's wife was surprised to find that Bladen died with little money on him despite having recently won a large sum at the races; his betting books were also missing, so there was no evidence of his having lent Palmer any money. Bladen's death certificate

A death certificate is either a legal document issued by a medical practitioner which states when a person died, or a document issued by a government civil registration office, that declares the date, location and cause of a person's death, as ...

listed Palmer as "present at the death", and stated the cause of death as "injury of the hip joint, 5 or 6 months; abscess

An abscess is a collection of pus that has built up within the tissue of the body. Signs and symptoms of abscesses include redness, pain, warmth, and swelling. The swelling may feel fluid-filled when pressed. The area of redness often extends b ...

in the pelvis".

Palmer's first son, William Brookes Palmer, was born towards the end of 1848 and christened in January 1849. He outlived his father, dying on 29 April 1926. The Palmers had four more children, all of whom died in infancy. The cause of death for each child was listed as " convulsions":

*Elizabeth Palmer. Died on 6 January 1851. She was about two and a half months old at the time of death.

*Henry Palmer. Died on 6 January 1852. He was about a month old.

*Frank Palmer. Died on 19 December 1852, only seven hours following his birth.

*John Palmer. Died on 27 January 1854. He was three or four days old.

As infant mortality

Infant mortality is the death of young children under the age of 1. This death toll is measured by the infant mortality rate (IMR), which is the probability of deaths of children under one year of age per 1000 live births. The under-five morta ...

was not uncommon at the time, these deaths were not initially seen as suspicious, though after Palmer's conviction in 1856 there was speculation that he had administered poison to the children to avoid the expense of more mouths to feed. By 1854 Palmer was heavily in debt and resorting to forging

Forging is a manufacturing process involving the shaping of metal using localized compressive forces. The blows are delivered with a hammer (often a power hammer) or a die. Forging is often classified according to the temperature at which i ...

his mother's signature to pay off creditors. He took out life insurance

Life insurance (or life assurance, especially in the Commonwealth of Nations) is a contract between an insurance policy holder and an insurer or assurer, where the insurer promises to pay a designated beneficiary a sum of money upon the death ...

on his wife with the Prince of Wales Insurance Company, and paid out a premium of £750 for a policy of £13,000. The death of Ann Palmer followed on 29 September 1854, at only 27 years old. She was believed to have died of cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

, as a cholera pandemic was affecting the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

(causing 23,000 deaths across the country).

Still heavily in debt, with two creditors (whom he owed £12,500 and £10,400) threatening to speak to his mother and thereby expose his fraud, Palmer attempted to take out life insurance on his brother, Walter, for the sum of £84,000. Unable to find a company willing to insure him for such a sum, he instead returned to the Prince of Wales Insurance Company, paying out a premium of £780 for a policy of £14,000. Walter was a drunk and soon became reliant on his brother, who readily plied him with several bottles of gin and brandy a day. He died on 16 August 1855. However the insurance company refused to pay up, and instead dispatched inspectors Simpson and Field to investigate. The pair found that Palmer had also been attempting to take out £10,000 worth of insurance on the life of George Bate, a farmer who was briefly under his employment. They found that Bate was either misinformed or lying about the details of his insurance policy, and they informed Palmer that the company would not pay out on the death of his brother and recommended a further enquiry into his death.

At about this time, Palmer was involved in an affair with Eliza Tharme, his housemaid. On 26 June/27 June 1855, Tharme gave birth to Alfred, Palmer's illegitimate son, thus increasing the financial burdens on the physician. With Palmer's life and debts spiralling out of control, he planned the murder of his erstwhile friend John Cook.

Murder of John Cook

John Parsons Cook, a sickly young man with an inherited fortune of £12,000, was a friend of Palmer. In November 1855, the pair attended the

John Parsons Cook, a sickly young man with an inherited fortune of £12,000, was a friend of Palmer. In November 1855, the pair attended the Shrewsbury

Shrewsbury ( , also ) is a market town, civil parish, and the county town of Shropshire, England, on the River Severn, north-west of London; at the 2021 census, it had a population of 76,782. The town's name can be pronounced as either 'Sh ...

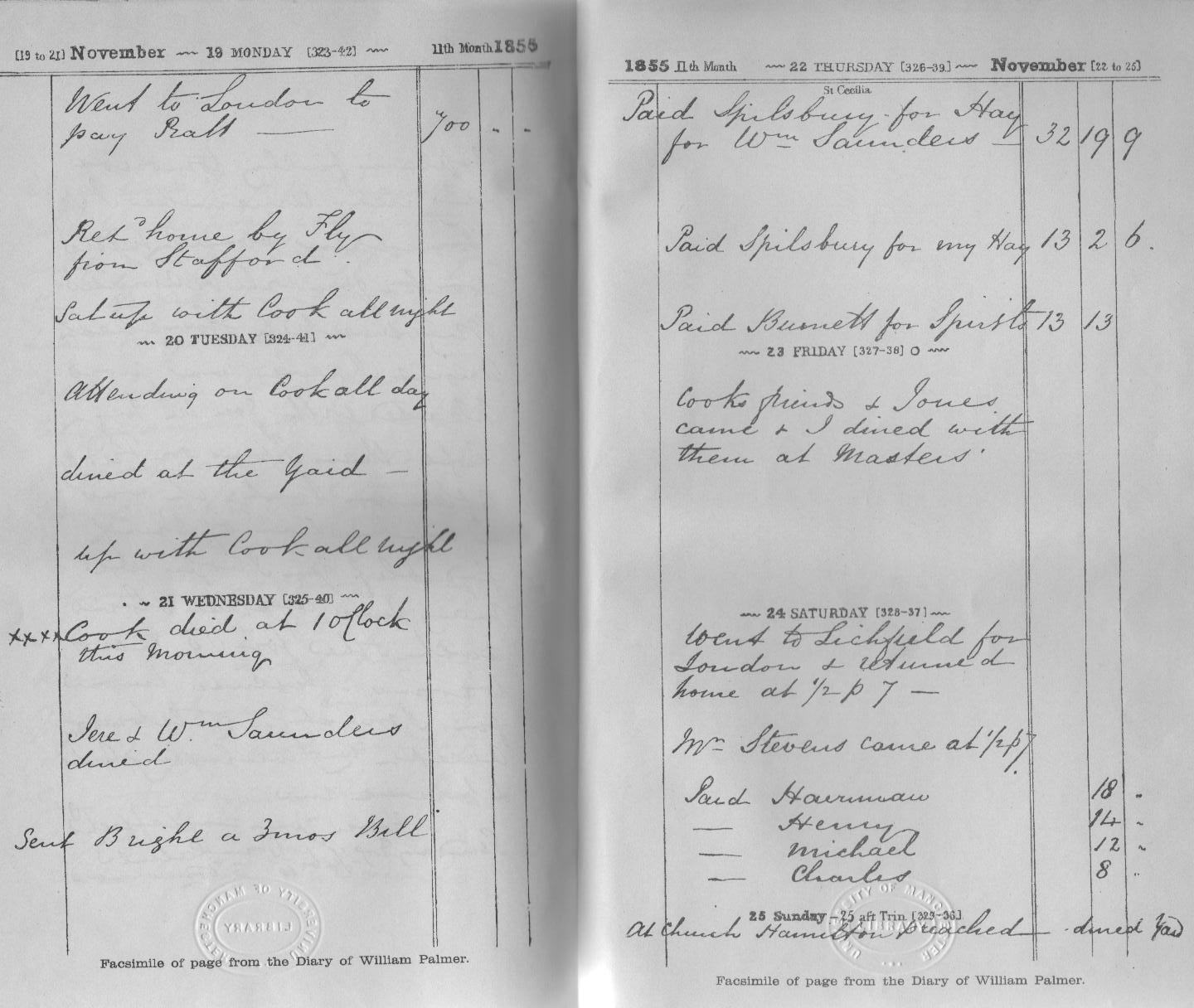

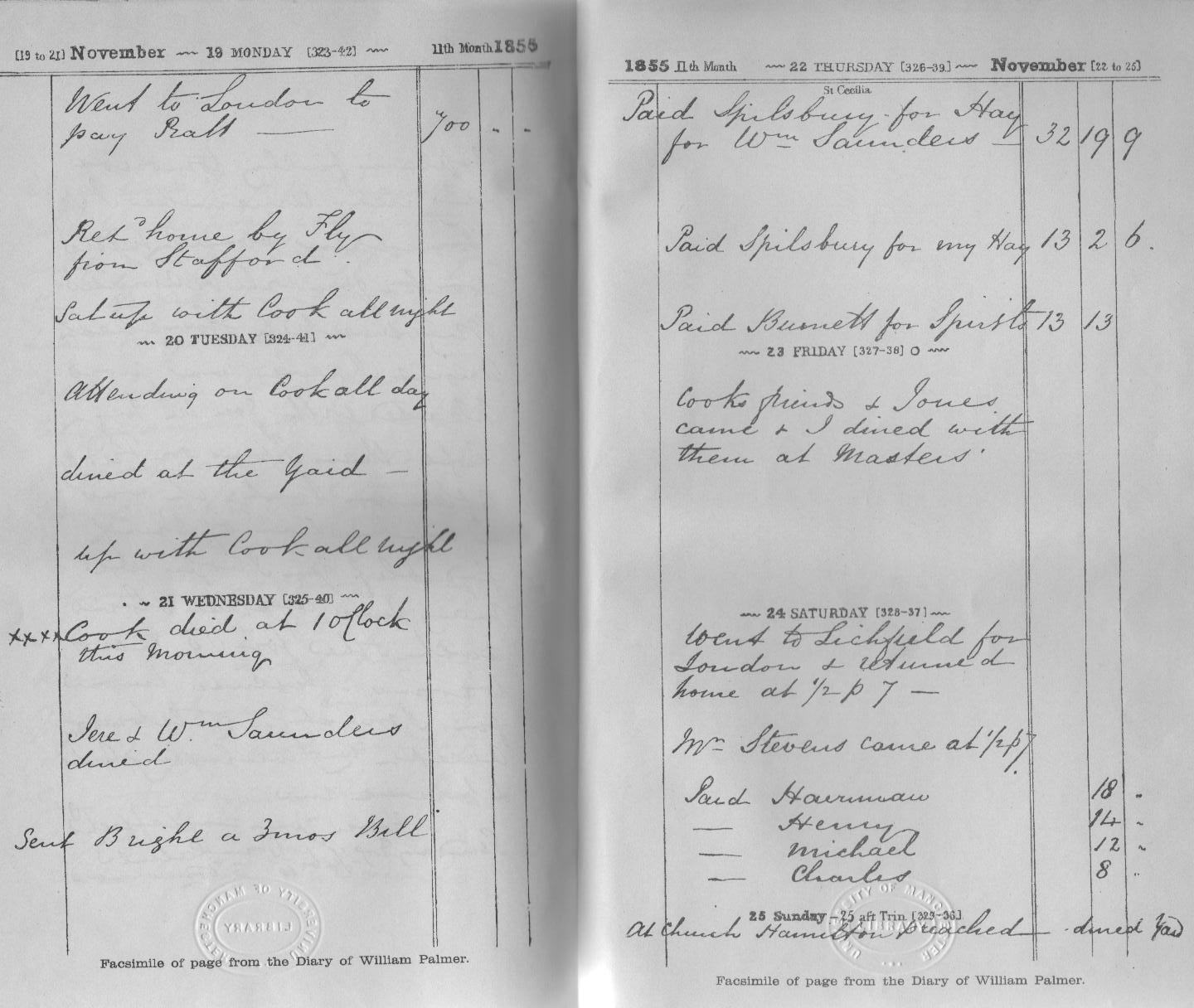

Handicap Stakes and bet on various horses between 13 and 15 November. Cook won £3,000 by betting on "Polestar"; Palmer lost heavily by betting instead on "the Chicken". Cook and Palmer had a celebration party at the Raven, a local drinking establishment. Already on 14 November, Cook was complaining that his gin had burnt his throat; Palmer responded by making a scene in which he attempted to convince bemused onlookers that there was nothing untoward in Cook's glass. Afterwards Cook was violently sick and told two friends, George Herring and Ishmael Fisher, that, "I believe that damn Palmer has been dosing me". On 15 November, Palmer and Cook returned to Rugeley, at which point Cook booked a room at the Talbot Arms.

Earlier on 14 November Palmer had received a letter from a creditor named Pratt, who threatened to visit his mother and ask for his money if Palmer himself would not pay up soon. The following day he bet heavily on a horse and lost.

Having seemingly recovered from his illness, Cook met with Palmer for a drink on 17 November, and soon found himself sick once again. At this point Palmer assumed responsibility for Cook; Cook's solicitor

A solicitor is a legal practitioner who traditionally deals with most of the legal matters in some jurisdictions. A person must have legally-defined qualifications, which vary from one jurisdiction to another, to be described as a solicitor and ...

, Jeremiah Smith, sent over a bottle of gin, which Palmer had in his possession before he sent it. Chambermaid Elizabeth Mills took a sip of the gin and subsequently fell ill; Cook was given the rest of the gin, and his vomiting became worse than ever. The next day, Palmer began collecting bets on behalf of Cook, bringing home £1,200. He then purchased three grains of strychnine

Strychnine (, , US chiefly ) is a highly toxic, colorless, bitter, crystalline alkaloid used as a pesticide, particularly for killing small vertebrates such as birds and rodents. Strychnine, when inhaled, swallowed, or absorbed through the eye ...

from the surgery of Dr Salt and put the grains into two pills, which he then administered to Cook. On 21 November, not long after Palmer administered two ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the formula . A stable binary hydride, and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinct pungent smell. Biologically, it is a common nitrogenous was ...

pills, Cook died in agony at about 1:00 am, screaming that he was suffocating.

On 23 November, William Stevens, Cook's stepfather, arrived to represent the family. Palmer informed him the deceased had lost his betting books, which he further claimed were of no use as all bets were cancelled once the gambler had died; he also told Stevens that Cook had £4,000 in outstanding bills. Stevens requested an inquest

An inquest is a judicial inquiry in common law jurisdictions, particularly one held to determine the cause of a person's death. Conducted by a judge, jury, or government official, an inquest may or may not require an autopsy carried out by a coro ...

, which was granted. Meanwhile, Palmer obtained a death certificate

A death certificate is either a legal document issued by a medical practitioner which states when a person died, or a document issued by a government civil registration office, that declares the date, location and cause of a person's death, as ...

from 80-year-old Dr Bamford, which listed the cause of death as 'apoplexy

Apoplexy () is rupture of an internal organ and the accompanying symptoms. The term formerly referred to what is now called a stroke. Nowadays, health care professionals do not use the term, but instead specify the anatomic location of the bleedi ...

'.

A post-mortem

An autopsy (post-mortem examination, obduction, necropsy, or autopsia cadaverum) is a surgical procedure that consists of a thorough examination of a corpse by dissection to determine the cause, mode, and manner of death or to evaluate any dis ...

examination of Cook's body took place at the Talbot Arms on 26 November, carried out by medical student Charles Devonshire and assistant Charles Newton, and overseen by Dr Harland and numerous other onlookers. Newton was drunk, and Palmer himself interfered with the examination, bumping into Newton and taking the stomach contents off in a jar for 'safe keeping'. The jars were sent off to Alfred Swaine Taylor

Alfred Swaine Taylor (11 December 1806 in Northfleet, Kent – 27 May 1880 in London) was an English toxicologist and medical writer, who has been called the "father of British forensic medicine". He was also an early experimenter in photography ...

, who complained that such poor quality samples were of no use to him, and a second post-mortem took place on 29 November. Postmaster

A postmaster is the head of an individual post office, responsible for all postal activities in a specific post office. When a postmaster is responsible for an entire mail distribution organization (usually sponsored by a national government), ...

Samuel Cheshire intercepted letters addressed to the coroner

A coroner is a government or judicial official who is empowered to conduct or order an inquest into Manner of death, the manner or cause of death, and to investigate or confirm the identity of an unknown person who has been found dead within th ...

on behalf of Palmer; Cheshire was later prosecuted for interfering with the mail and given two years in prison. Palmer also wrote to the coroner himself, requesting that the verdict of death be given as natural causes

In many legal jurisdictions, the manner of death is a determination, typically made by the coroner, medical examiner, police, or similar officials, and recorded as a vital statistic. Within the United States and the United Kingdom, a distinct ...

, enclosing in his letter a £10 note.

Taylor found no evidence of poison, but still stated that it was his belief that Cook had been poisoned. The jury at the inquest delivered their verdict on 15 December, stating that the "Deceased died of poison wilfully administered to him by William Palmer"; at the time, this verdict could be legally handed down at an inquest.

Arrest and trial

Palmer was arrested on the charge of murder and forgery (a creditor had told the police his suspicions that Palmer had been forging his mother's signature) and detained at Stafford Gaol; he threatened to go onhunger strike

A hunger strike is a method of non-violent resistance in which participants fast as an act of political protest, or to provoke a feeling of guilt in others, usually with the objective to achieve a specific goal, such as a policy change. Most ...

, but backed down when the governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

informed him that this would lead to his being force fed

Force-feeding is the practice of feeding a human or animal against their will. The term ''gavage'' (, , ) refers to supplying a substance by means of a small plastic feeding tube passed through the nose ( nasogastric) or mouth (orogastric) into t ...

.

An Act of Parliament

Acts of Parliament, sometimes referred to as primary legislation, are texts of law passed by the Legislature, legislative body of a jurisdiction (often a parliament or council). In most countries with a parliamentary system of government, acts of ...

(the Central Criminal Court Act 1856

The Central Criminal Court Act 1856Short Title authorised by the Short Titles Act 1896 (19 & 20 Vict., c.16), originally known as the Trial of Offences Act 1856 and popularly known as Palmer's Act, was an Act of the Parliament of the United Ki ...

) was passed to allow the trial to be held at the Old Bailey

The Central Criminal Court of England and Wales, commonly referred to as the Old Bailey after the street on which it stands, is a criminal court building in central London, one of several that house the Crown Court of England and Wales. The s ...

in London, as it was felt that a fair jury

A jury is a sworn body of people (jurors) convened to hear evidence and render an impartiality, impartial verdict (a Question of fact, finding of fact on a question) officially submitted to them by a court, or to set a sentence (law), penalty o ...

could not be found in Staffordshire, where detailed accounts of the case and the deaths of his children were printed by local newspapers. However, an alternative hypothesis is that Palmer was a popular figure in Rugeley and would not have been found guilty by a Staffordshire jury: the implication being that the trial location was moved for political reasons so as to secure a guilty verdict. Lord Chief Justice Campbellthe senior judge at Palmer's trialsuggested in his autobiography that, had Palmer been tried at Stafford

Stafford () is a market town and the county town of Staffordshire, in the West Midlands region of England. It lies about north of Wolverhampton, south of Stoke-on-Trent and northwest of Birmingham. The town had a population of 70,145 in t ...

Assizes Court, he would have been found not guilty.

The Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all national ...

also ordered that the bodies of Ann and Walter Palmer be exhumed and re-examined; Walter was too badly decomposed, though Dr Taylor found antimony

Antimony is a chemical element with the symbol Sb (from la, stibium) and atomic number 51. A lustrous gray metalloid, it is found in nature mainly as the sulfide mineral stibnite (Sb2S3). Antimony compounds have been known since ancient time ...

in all the organs in Ann's body.

Palmer's defence

Defense or defence may refer to:

Tactical, martial, and political acts or groups

* Defense (military), forces primarily intended for warfare

* Civil defense, the organizing of civilians to deal with emergencies or enemy attacks

* Defense industr ...

was led by Mr Serjeant William Shee

Sir William Shee (24 June 1804 – 1868) was an Anglo-Irish politician, lawyer and judge, the first Roman Catholic judge to sit in England and Wales since the Reformation.

Early life and legal career

Shee was born in Finchley, Middlesex. His f ...

.Barker (2004) The defence case suffered adverse comment from the judge because Shee had, against all rules and conventions of professional conduct, told the jury that he personally believed Palmer to be innocent. The prosecution

A prosecutor is a legal representative of the prosecution in states with either the common law adversarial system or the civil law inquisitorial system. The prosecution is the legal party responsible for presenting the case in a criminal trial ...

team of Alexander Cockburn

Alexander Claud Cockburn ( ; 6 June 1941 – 21 July 2012) was a Scottish-born Irish-American political journalist and writer. Cockburn was brought up by British parents in Ireland, but lived and worked in the United States from 1972. Together ...

and John Walter Huddleston

Sir John Walter Huddleston (8 September 1815 – 5 December 1890) was an English judge, formerly a criminal lawyer who had established an eminent reputation in various '' causes célèbres''.

As a Baron of the Exchequer of Pleas, he was styled ...

possessed fine forensic minds and proved forceful advocates, especially in demolishing defence witness Jeremiah Smith, who had insisted that he had no knowledge of Palmer's taking out life insurance on his brother, despite Smith's signature being on the form. Palmer expressed his admiration for Cockburn's cross-examination

In law, cross-examination is the interrogation of a witness called by one's opponent. It is preceded by direct examination (in Ireland, the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, South Africa, India and Pakistan known as examination-in-chief) and m ...

after the verdict through the racing metaphor, "It was the riding that did it."Knott (1912) ''p.''3

Circumstantial evidence came to light:

* Elizabeth Mills said that as Cook was dying, he accused Palmer of murder.

* Charles Newton told the jury that he had seen Palmer purchasing strychnine.

* Chemist Mr Salt admitted selling Palmer strychnine in the belief that he was using it to poison a dog. He also admitted that he had failed to record the sale in his poisons book as required by law.

* Charles Roberts, another chemist, also admitted selling Palmer strychnine without noting the sale in his poisons book.

Palmer's financial situation was also explained, money lender Thomas Pratt telling the court he lent money to the accused at 60% interest, and bank manager Mr Stawbridge confirming that Palmer's bank balance had stood at £9 at 3 November 1855.

The cause of Cook's death was hotly disputed, with each side bringing out medical witnesses. Few medical witnesses actually had any experience in human cases of strychnine poisoning and their testimony would have been considered weak by 21st-century standards.

* Dr Bamford was ill, and his stated cause as congestion of the brain was dismissed by other witnesses; the prosecution told the jury that he had become mentally suspect in his old age.

* The prosecution witnesses, including Alfred Swaine Taylor, stated the cause of death as 'tetanus

Tetanus, also known as lockjaw, is a bacterial infection caused by ''Clostridium tetani'', and is characterized by muscle spasms. In the most common type, the spasms begin in the jaw and then progress to the rest of the body. Each spasm usually ...

due to strychnine'.

* Shee summed up his case to the jury by stating that, if the prosecution were correct: "Never therefore, were circumstances more favourable for detection of the poison and yet none was found." He summoned fifteen medical witnesses who stated that the poison should have been found in the stomach (the contents of which had disappeared during the post-mortem).

The prosecution had the last word, and an image was painted of Palmer as a man desperately in need of money in order to avoid debtors' prison

A debtors' prison is a prison for people who are unable to pay debt. Until the mid-19th century, debtors' prisons (usually similar in form to locked workhouses) were a common way to deal with unpaid debt in Western Europe.Cory, Lucinda"A Histori ...

, who murdered his friend for his money and who had covered his tracks by sabotaging the post-mortem. The jury deliberated for just over an hour before returning a verdict of guilty. Lord Campbell handed down a death sentence

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that ...

, to no reaction from Palmer.

Execution

Approximately 30,000 people were at Stafford prison on 14 June 1856 to see Palmer's

Approximately 30,000 people were at Stafford prison on 14 June 1856 to see Palmer's public execution

A public execution is a form of capital punishment which "members of the general public may voluntarily attend." This definition excludes the presence of only a small number of witnesses called upon to assure executive accountability. The purpose ...

by hanging

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a noose or ligature around the neck.Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Hanging as method of execution is unknown, as method of suicide from 1325. The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' states that hanging i ...

at the hands of George Smith. As he stepped onto the gallows, Palmer is said to have looked at the trapdoor and exclaimed, "Are you sure it's safe?"

The prison governor asked Palmer to confess his guilt before the end, which resulted in the following exchange of words:

: "Cook did not die from strychnine

Strychnine (, , US chiefly ) is a highly toxic, colorless, bitter, crystalline alkaloid used as a pesticide, particularly for killing small vertebrates such as birds and rodents. Strychnine, when inhaled, swallowed, or absorbed through the eye ...

."

: "This is no time for quibbling – did you, or did you not, kill Cook?"

: "The Lord Chief Justice summed up for poisoning by strychnine."

Palmer was buried beside the prison chapel in a grave filled with quicklime

Calcium oxide (CaO), commonly known as quicklime or burnt lime, is a widely used chemical compound. It is a white, caustic, alkaline, crystalline solid at room temperature. The broadly used term "''lime''" connotes calcium-containing inorganic ma ...

. After he was hanged his mother is said to have commented: "They have hanged my saintly Billy." Shortly after the execution, a newspaper reported:

: "It is stated that the rope that hanged Palmer is selling in Lockmaben, Dumfrieshire

Dumfriesshire or the County of Dumfries or Shire of Dumfries (''Siorrachd Dhùn Phris'' in Gaelic) is a historic county and registration county in southern Scotland. The Dumfries lieutenancy area covers a similar area to the historic county.

...

, at 5s. per inch. The seller is a man from Dudley, where Smith the hangman resides. The 'interesting relic,' it is said, meets with ready purchasers. The rope has also been selling extensively in England, it is said, and of course is being spun as the demand for it increases."

Some scholars believe that the evidence should not have been enough to convict him, and that the summing up of the judge was prejudicial. On 20 May 1946, '' The Sentinel'' published a final piece of evidence not included in the trial, found by Mrs E. Smith, widow of the former coroner for South West London; it was a prescription for opium

Opium (or poppy tears, scientific name: ''Lachryma papaveris'') is dried latex obtained from the seed capsules of the opium poppy ''Papaver somniferum''. Approximately 12 percent of opium is made up of the analgesic alkaloid morphine, which i ...

written in Palmer's handwriting, on the reverse of which was a chemist's bill for 10d worth of strychnine and opium.

Cultural references

The fictional character of Inspector Bucket inCharles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian e ...

's ''Bleak House

''Bleak House'' is a novel by Charles Dickens, first published as a 20-episode serial between March 1852 and September 1853. The novel has many characters and several sub-plots, and is told partly by the novel's heroine, Esther Summerson, and ...

'' (1853) is reputed to be based on Charles Frederick Field, the policeman who investigated Walter Palmer's death for his insurers. Dickens once called Palmer "the greatest villain that ever stood in the Old Bailey

The Central Criminal Court of England and Wales, commonly referred to as the Old Bailey after the street on which it stands, is a criminal court building in central London, one of several that house the Crown Court of England and Wales. The s ...

."

A wax effigy of Palmer was displayed in the Chamber of Horrors at Madame Tussaud's waxwork museum from 1857 until 1979.

In the novel ''Phineas Redux

''Phineas Redux'' is a novel by Anthony Trollope, first published in 1873 as a serial in ''The Graphic''. It is the fourth of the " Palliser" series of novels and the sequel to the second book of the series, ''Phineas Finn''.

Synopsis

His be ...

'' (1873) by Anthony Trollope

Anthony Trollope (; 24 April 1815 – 6 December 1882) was an English novelist and civil servant of the Victorian era. Among his best-known works is a series of novels collectively known as the '' Chronicles of Barsetshire'', which revolves ar ...

, lawyers defending Phineas Finn

''Phineas Finn'' is a novel by Anthony Trollope and the name of its leading character. The novel was first published as a monthly serial from October 1867 to May 1868 in ''St Paul's Magazine''. It is the second of the " Palliser" series of novel ...

against a charge of murder make an abstruse allusion to the case. They imply that Palmer had been wrongly convicted and hanged and that their client should avoid giving too detailed an account of his movements on the night of the crime to avoid a similar fate.

In the Sherlock Holmes short story "The Adventure of the Speckled Band

"The Adventure of the Speckled Band" is one of 56 short Sherlock Holmes stories written by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the eighth story of twelve in the collection ''The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes''. It was originally published in '' Strand Maga ...

" (1892), while commenting on the apparent villain, Dr Grimesby Roylott, Holmes tells Dr Watson that when a doctor goes bad he is "the first of criminals." Holmes then illustrates this point with the comment that Palmer and Edward William Pritchard

Edward William Pritchard (6 December 1825 – 28 July 1865) was an English doctor who was convicted of murdering his wife and mother-in-law by poisoning them. He was also suspected of murdering a servant girl, but was never tried for this crime.

...

were at the "head of their profession." Since neither was considered a good doctor, and Pritchard was considered something of a quack by the medical fraternity in Glasgow, the "profession" Holmes meant was that of murder.

The incident involving Palmer at the autopsy of Cook is referred to in Dorothy L. Sayers

Dorothy Leigh Sayers (; 13 June 1893 – 17 December 1957) was an English crime writer and poet. She was also a student of classical and modern languages.

She is best known for her mysteries, a series of novels and short stories set between th ...

's 1928 murder mystery novel ''The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club

''The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club'' is a 1928 mystery novel by Dorothy L. Sayers, her fourth featuring Lord Peter Wimsey. Much of the novel is set in the Bellona Club, a fictional London club for war veterans (Bellona being a Roman god ...

''. The doctor doing the post-mortem on the victim says, as he transfers the stomach contents to a jar: "...Look out! You'll have it over. Ha! ha! That was a near thing. Reminds me of Palmer, you know - and Cook's stomach - always think that a very funny story, ha! ha!..." Sayer's 1927 mystery ''Unnatural Death

In many legal jurisdictions, the manner of death is a determination, typically made by the coroner, medical examiner, police, or similar officials, and recorded as a vital statistic. Within the United States and the United Kingdom, a distinct ...

'' refers to Palmer as an example of someone who committed numerous undetected murders (until, with Cook, he employed means that were too flamboyant).

Alfred Hitchcock

Sir Alfred Joseph Hitchcock (13 August 1899 – 29 April 1980) was an English filmmaker. He is widely regarded as one of the most influential figures in the history of cinema. In a career spanning six decades, he directed over 50 featur ...

's 1941 film ''Suspicion

Suspicion is a feeling of mistrust.

Suspicion(s), The Suspicion, or Suspicious may also refer to:

Film and television Film

* ''Suspicion'' (1918 film), an American silent film directed by John M. Stahl

* ''Suspicion'' (1941 film), an American ...

'' invokes the memory of "Richard Palmer," a notorious murderer who killed one of his victims through overindulgence in brandy. In the scene between Lina (Joan Fontaine

Joan de Beauvoir de Havilland (October 22, 1917 – December 15, 2013), known professionally as Joan Fontaine, was a British-American actress who is best known for her starring roles in Hollywood films during the "Golden Age". Fontaine appeared ...

) and an author of murder mysteries (Auriol Lee

Auriol Lee (13 September 1880 – 2 July 1941) was a popular British stage actress who became a successful West End and Broadway theatrical producer and director.

Biography

She was born in Maddox Street in the London district of St George's Han ...

) who lives in her village, the death of a mutual friend is said to have a precedent in this real-life murder by "Richard" Palmer. Lina's husband (Cary Grant

Cary Grant (born Archibald Alec Leach; January 18, 1904November 29, 1986) was an English-American actor. He was known for his Mid-Atlantic accent, debonair demeanor, light-hearted approach to acting, and sense of comic timing. He was one o ...

) is suspected of having borrowed a book, ''The Trial of Richard Palmer,'' to study techniques of murder.

William Palmer was portrayed by actor Jay Novello

Jay Novello (born Michael Romano, August 22, 1904 – September 2, 1982) was an American radio, film, and television character actor.

Early life

Novello was born in Chicago to Joseph Romano and Maria (Salemme) Romano. He had three sibling ...

on the CBS

CBS Broadcasting Inc., commonly shortened to CBS, the abbreviation of its former legal name Columbia Broadcasting System, is an American commercial broadcast television and radio network serving as the flagship property of the CBS Entertainm ...

radio series '' Crime Classics'' in the 7 October 1953 episode entitled "The Hangman and William Palmer, Who Won?"

Robert Graves

Captain Robert von Ranke Graves (24 July 1895 – 7 December 1985) was a British poet, historical novelist and critic. His father was Alfred Perceval Graves, a celebrated Irish poet and figure in the Gaelic revival; they were both Celtic ...

's final historical novel, ''They Hanged My Saintly Billy'' (1957), defends Palmer, offering Graves's trademark "reconstruction of a damaged or maligned reputation" (p. xxv).

The film '' The Life and Crimes of William Palmer'' was released in 1998, with Keith Allen playing the part of Palmer.

The salutation "What's your poison?" is thought to be a reference to the events.Davenport-Hines (2004)

See also

* John Bodkin Adams (a doctor suspected of murder for financial gain) *Thomas Neill Cream

Thomas Neill Cream (27 May 1850 – 15 November 1892), also known as the Lambeth Poisoner, was a Scottish-Canadian medical doctor and serial killer who poisoned his victims with strychnine. Over the course of his career, he murdered up t ...

(aka the Lambeth Poisoner, a doctor who murdered with poison)

*Harold Shipman

Harold Frederick Shipman (14 January 1946 – 13 January 2004), known by the public as Doctor Death and to acquaintances as Fred Shipman, was an English general practitioner and serial killer. He is considered to be one of the most prolif ...

(a doctor convicted of 15 murders, but suspected of some 250 murders in total)

*Michael Swango

Michael Joseph Swango (born October 21, 1954) is an American serial killer and licensed physician who is estimated to have been involved in as many as 60 fatal poisonings of patients and colleagues, although he admitted to only causing four deat ...

(a physician suspected of poisoning around 60 people)

*List of serial killers by country

This is a list of notable serial killers, by the country where most of the killings occurred.

Convicted serial killers by country Afghanistan

*Abdullah Shah: killed at least 20 travelers on the road from Kabul to Jalalabad while serving under ...

Notes

Bibliography

*Barker, G. F. R. (2004)Shee, Sir William (1804–1868)

, rev. Hugh Mooney, ''

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

'', Oxford University Press, accessed 24 July 2007

*Bates, Stephen (2014) ''The Poisoner: The Life and Crimes of Victorian England's Most Notorious Doctor'', Overlook,

*Davenport-Hines, R. (2004)Palmer,_William_

/nowiki>_(1824–1856).html" ;"title="/nowiki> the Rugeley Poisoner

/nowiki> (1824–1856)">/nowiki> the Rugeley Poisoner

/nowiki> (1824–1856), ''

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

'', Oxford University Press, accessed 20 July 2007

*

*

*McCormick, Ian. (Ed.) ''Antigua, Penny, Puce AND They Hanged My Saintly Billy.'' London Carcanet Press, 2003.

*Graves,Robert"They hanged my saintly Billy".Cassell and Co,London1957

External links

williampalmer.co.uk

on the BBC

Staffordshire Past Track

– William Palmer * {{DEFAULTSORT:Palmer, William 1824 births 1855 murders in the United Kingdom 1856 deaths 19th-century English medical doctors 19th-century executions by England and Wales English people convicted of murder Executed people from Staffordshire Medical practitioners convicted of murdering their patients Murderers for life insurance money People convicted of murder by England and Wales People from Rugeley Poisoners Suspected serial killers