William Maxwell Evarts on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

William Maxwell Evarts (February 6, 1818February 28, 1901) was an American lawyer and statesman from New York who served as U.S. Secretary of State,

''Encyclopedia.com''. Retrieved February 9, 2022. He was not involved in the antislavery crusade except for his involvement in the Lemmon Slave Case. Evarts never showed the talent or inclination for electoral politics, but he early became relied on by party leaders to perform oratorical or public ceremonial functions. In early 1852 he made two major addresses at large meetings for

From 1865 to 1868, Evarts was on the team of lawyers prosecuting

From 1865 to 1868, Evarts was on the team of lawyers prosecuting  Evarts served as counsel for President-elect

Evarts served as counsel for President-elect

U.S. Attorney General

The United States attorney general (AG) is the head of the United States Department of Justice, and is the chief law enforcement officer of the federal government of the United States. The attorney general serves as the principal advisor to the p ...

and U.S. Senator

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and powe ...

from New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

. He was renowned for his skills as a litigator

-

A lawsuit is a proceeding by a party or parties against another in the civil court of law. The archaic term "suit in law" is found in only a small number of laws still in effect today. The term "lawsuit" is used in reference to a civil actio ...

and was involved in three of the most important causes of American political jurisprudence

Jurisprudence, or legal theory, is the theoretical study of the propriety of law. Scholars of jurisprudence seek to explain the nature of law in its most general form and they also seek to achieve a deeper understanding of legal reasoning a ...

in his day: the impeachment of a president, the Geneva arbitration and the contests before the electoral commission

An election commission is a body charged with overseeing the implementation of electioneering process of any country. The formal names of election commissions vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, and may be styled an electoral commission, a c ...

to settle the presidential election of 1876.

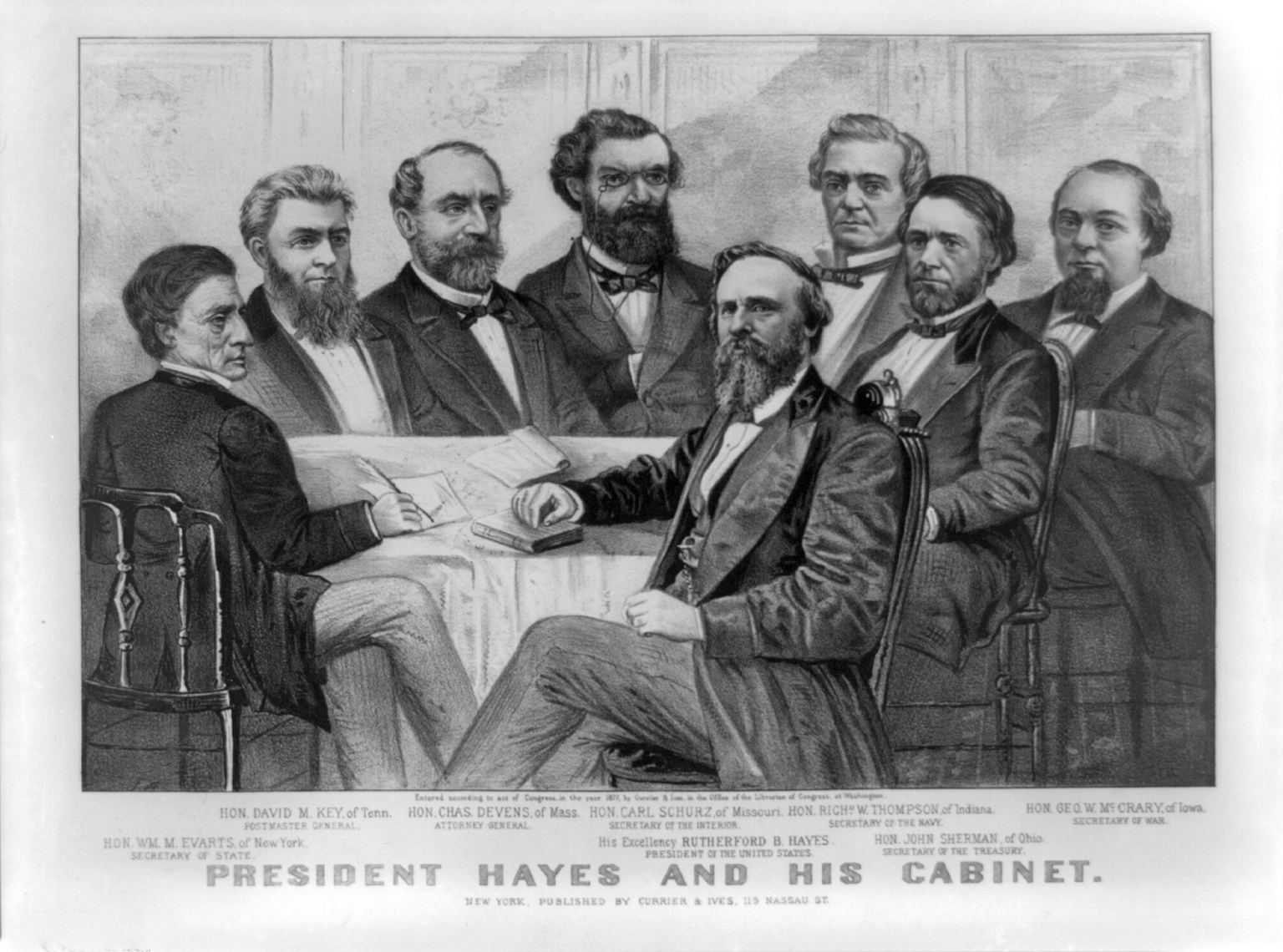

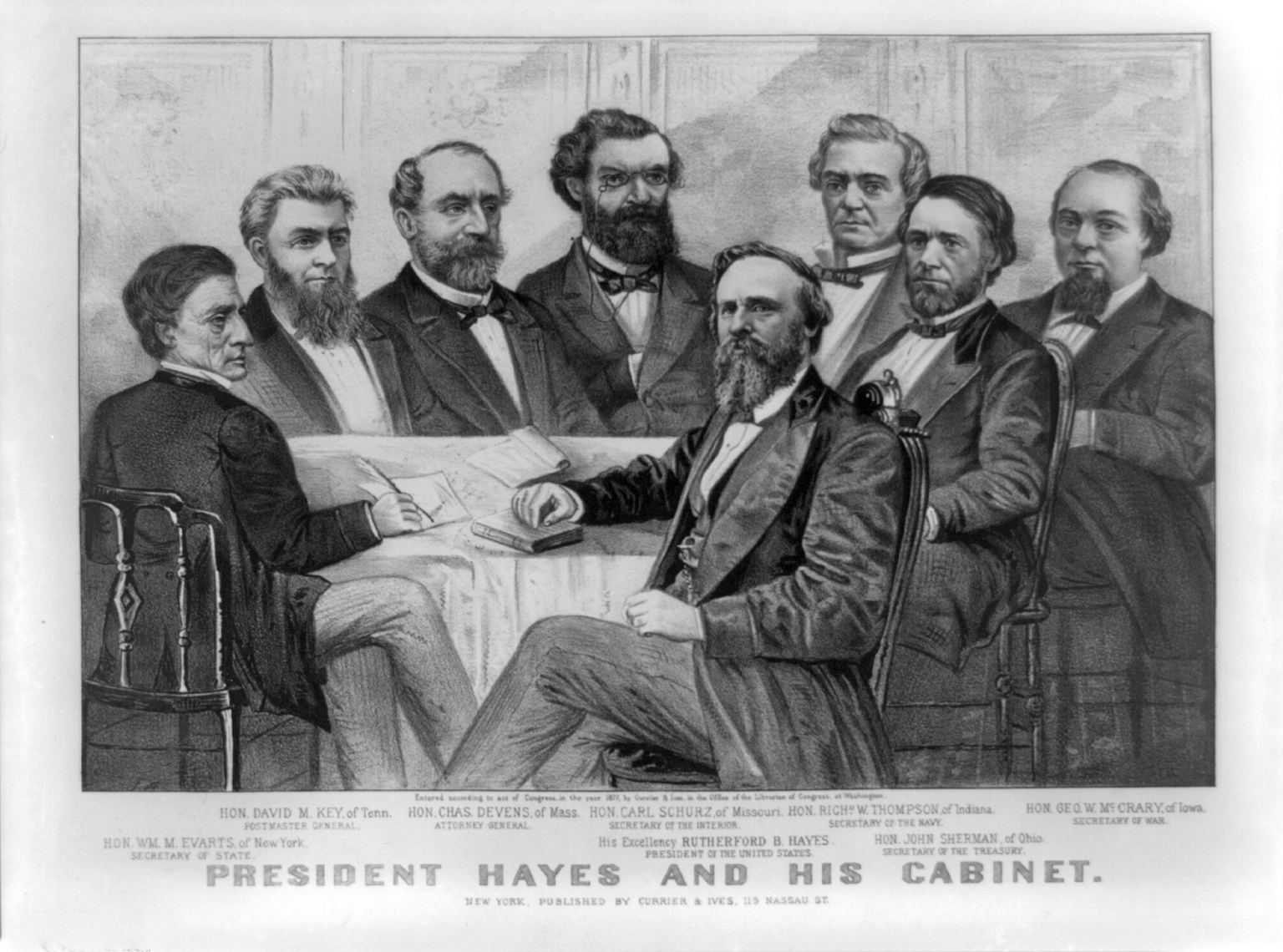

During the presidency of Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governor ...

, the reform-minded Evarts was an active member among the "Half-Breed

Half-breed is a term, now considered offensive, used to describe anyone who is of mixed race; although, in the United States, it usually refers to people who are half Native American and half European/white.

Use by governments United States

In ...

" faction of the Republican Party, which emphasized support for civil service reform, bolstering opposition towards conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization i ...

"Stalwarts

The Stalwarts were a faction of the Republican Party that existed briefly in the United States during and after Reconstruction and the Gilded Age during the 1870s and 1880s. Led by U.S. Senator Roscoe Conkling—also known as "Lord Roscoe"—S ...

" who defended the spoils system

In politics and government, a spoils system (also known as a patronage system) is a practice in which a political party, after winning an election, gives government jobs to its supporters, friends (cronyism), and relatives (nepotism) as a reward ...

and advocated on behalf of Southern blacks.

Family, education and marriage

William M. Evarts was born on February 6, 1818 inCharlestown, Massachusetts

Charlestown is the oldest neighborhood in Boston, Massachusetts, in the United States. Originally called Mishawum by the Massachusett tribe, it is located on a peninsula north of the Charles River, across from downtown Boston, and also adjoins t ...

, the son of Jeremiah Evarts

Jeremiah F. Evarts (February 3, 1781 – May 10, 1831), also known by the pen name William Penn, was a Christian missionary, reformer, and activist for the rights of American Indians in the United States, and a leading opponent of the Indian remo ...

and Mehitabel Barnes Sherman. Evarts's father, a native of Vermont, a "lawyer of fair practice and good ability," (Reprinted from the ''New York Herald'', March 7.)

and later the editor of ''The Panoplist ''The Panoplist'' was a religious monthly magazine printed from 1805 until 1820 edited by Jeremiah Evarts

Jeremiah F. Evarts (February 3, 1781 – May 10, 1831), also known by the pen name William Penn, was a Christian missionary, reformer, and a ...

'', a religious journal, and corresponding secretary of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions

The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) was among the first American Christian missionary organizations. It was created in 1810 by recent graduates of Williams College. In the 19th century it was the largest and most imp ...

(during a time of "fervor in mission propagandism") who led the fight against Indian removal

Indian removal was the United States government policy of forced displacement of self-governing tribes of Native Americans from their ancestral homelands in the eastern United States to lands west of the Mississippi Riverspecifically, to a de ...

s, died when William was thirteen. William's mother was the daughter of Roger Sherman

Roger Sherman (April 19, 1721 – July 23, 1793) was an American statesman, lawyer, and a Founding Father of the United States. He is the only person to sign four of the great state papers of the United States related to the founding: the Cont ...

, Connecticut founding father, a signatory to the Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the ...

, the Articles of Confederation

The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union was an agreement among the 13 Colonies of the United States of America that served as its first frame of government. It was approved after much debate (between July 1776 and November 1777) by ...

and the Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of Legal entity, entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When ...

. (Subscription required.)

Evarts attended Boston Latin School

The Boston Latin School is a public exam school in Boston, Massachusetts. It was established on April 23, 1635, making it both the oldest public school in the British America and the oldest existing school in the United States. Its curriculum f ...

, then Yale College

Yale College is the undergraduate college of Yale University. Founded in 1701, it is the original school of the university. Although other Yale schools were founded as early as 1810, all of Yale was officially known as Yale College until 1887, ...

. In his college class were Morrison Waite

Morrison Remick "Mott" Waite (November 29, 1816 – March 23, 1888) was an American attorney, jurist, and politician from Ohio. He served as the seventh chief justice of the United States from 1874 until his death in 1888. During his tenur ...

, later Chief Justice of the United States, Samuel J. Tilden

Samuel Jones Tilden (February 9, 1814 – August 4, 1886) was an American politician who served as the 25th Governor of New York and was the Democratic candidate for president in the disputed 1876 United States presidential election. Tilden was ...

, future New York Governor and Democratic presidential nominee and one of the contestants in the electoral commissions controversy in which Evarts acted as counsel for the Republicans, chemist Benjamin Silliman, Jr.

Benjamin Silliman Jr. (December 4, 1816 – January 14, 1885) was a professor of chemistry at Yale University and instrumental in developing the oil industry.

His father Benjamin Silliman Sr., also a famous Yale chemist, developed the process of ...

, and Edwards Pierrepont

Edwards Pierrepont (March 4, 1817 – March 6, 1892) was an American attorney, reformer, jurist, traveler, New York U.S. Attorney, U.S. Attorney General, U.S. Minister to England, and orator.''West's Encyclopedia of American Law'' (2005), "Pierre ...

, later United States Attorney General. While at Yale he became a member of two secret societies, the literary and debate oriented Linonian Society

Linonia is a literary and debating society founded in 1753 at Yale University. It is the university's second-oldest secret society.

History

Linonia was founded on September 12, 1753, as Yale College's second literary and debating society, af ...

and Skull and Bones

Skull and Bones, also known as The Order, Order 322 or The Brotherhood of Death, is an undergraduate senior secret student society at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. The oldest senior class society at the university, Skull and Bone ...

;* he later extolled the former and much later denounced all such secret societies. Evarts was one of the founders of ''Yale Literary Magazine

The ''Yale Literary Magazine'', founded in 1836, is the oldest student literary magazine in the United States and publishes poetry, fiction, and visual art by Yale undergraduates twice per academic year. Notable alumni featured in the magazine whi ...

'' in 1836.. He graduated third in his class in 1837.

After college he moved to Windsor, Vermont

Windsor is a town in Windsor County, Vermont, United States. As the "Birthplace of Vermont", the town is where the Constitution of Vermont was adopted in 1777, thus marking the founding of the Vermont Republic, a sovereign state until 1791, when ...

, where he studied law in the office of Horace Everett

Horace Everett (July 17, 1779 – January 30, 1851) was an American politician. He served as a United States representative from Vermont.

Biography

Everett was born in Foxboro, Massachusetts. His father was John Everett; his mother was Melatiah ...

and taught school to save money for law school. He attended Harvard Law School

Harvard Law School (Harvard Law or HLS) is the law school of Harvard University, a private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1817, it is the oldest continuously operating law school in the United States.

Each class ...

for a year, where he "won the respect of Professors Joseph Story

Joseph Story (September 18, 1779 – September 10, 1845) was an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, serving from 1812 to 1845. He is most remembered for his opinions in ''Martin v. Hunter's Lessee'' and ''United States ...

and Simon Greenleaf

Simon Greenleaf (December 5, 1783 – October 6, 1853), was an American lawyer and jurist. He was born at Newburyport, Massachusetts before moving to New Gloucester where he was admitted to the Cumberland County bar.

Early life and legal c ...

." Evarts completed his legal studies

Jurisprudence, or legal theory, is the theoretical study of the propriety of law. Scholars of jurisprudence seek to explain the nature of law in its most general form and they also seek to achieve a deeper understanding of Reason#Logical rea ...

under attorney Daniel Lord

''For the Catholic priest and writer, see Daniel A. Lord''

Daniel Lord (September 23, 1795 – March 4, 1868) was a prominent New York City attorney. His firm was eventually joined by his son-in-law Henry Day and son Daniel Lord Jr. to form Lord D ...

of New York City and was admitted to the bar

An admission to practice law is acquired when a lawyer receives a license to practice law. In jurisdictions with two types of lawyer, as with barristers and solicitors, barristers must gain admission to the bar whereas for solicitors there are dist ...

in 1841.

He married Helen Minerva Bingham Wardner in 1843. She was the daughter of Allen Wardner

Allen Wardner (December 13, 1786 – August 29, 1877) was a Vermont banker, businessman and politician who served as Vermont State Treasurer, State Treasurer. He was also the Parent-in-law#Fathers-in-law, father-in-law of United States Attorney ...

, a prominent businessman and banker who served as Vermont State Treasurer

The State Treasurer's Office is responsible for several administrative and service duties, in accordance with Vermont Statutes. These include: investing state funds; issuing state bonds; serving as the central bank for state agencies; managing the ...

. They had 12 children between 1845 and 1862, all born in New York City.

Private practice

After admission to the bar Evarts joined the law office of Daniel Lord. One of his first cases involved the trial of the infamous forgerMonroe Edwards

Monroe Edwards (1808 – January 27, 1847) was an American slave trader, forger, and criminal who was the subject of a well-publicized trial and conviction in 1842. Originally from Kentucky, Edwards moved to New Orleans then settled in Texa ...

. Evarts served as a junior counsel for the defense, which was headed by Senator John J. Crittenden

John Jordan Crittenden (September 10, 1787 July 26, 1863) was an American statesman and politician from the U.S. state of Kentucky. He represented the state in the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate and twice served as United ...

of Kentucky. Edwards was convicted, but Evarts's handling of his duties earned him notice as a promising lawyer.

In 1851, Evarts began his partnership with Charles F. Southmayd (the firm was then named Butler, Evarts & Southmayd), a partnership that would last for the rest of his professional career in one form or another. In 1859 Evarts invited Joseph Hodges Choate

Joseph Hodges Choate (January 24, 1832 – May 14, 1917) was an American lawyer and diplomat. Choate was associated with many of the most famous litigations in American legal history, including the Kansas prohibition cases, the Chinese exclusi ...

to join the firm (which then became Evarts, Southmayd & Choate), and the firm then had a trial litigator in many ways as talented as Evarts. But it was Southmayd that Evarts depended on to prepare the case, because Southmayd, it was said, "was a lawyer of remarkable knowledge and capacity and dexterity in working up a case." In court, "especially before a jury," however, it was Evarts who shined.

In 1855, the State of Virginia hired attorneys (including the eminent Charles O'Conor Charles O'Conor may refer to:

* Charles O'Conor (historian) (1710–1791), Irish writer, historian, and antiquarian

* Charles O'Conor (priest) (1764–1828), Irish priest and historian, grandson of the above

* Charles O'Conor (American politician) ( ...

) to contest the decision of the New York Superior Court releasing eight black slaves in the famous Lemmon Slave Case. When Ogden Hoffman

Ogden Hoffman (October 13, 1794 – May 1, 1856) was an American lawyer and politician who served two terms in the United States House of Representatives.

Life

Ogden Hoffman was born on October 13, 1794, the son of New York Attorney General Jos ...

, the New York Attorney General, died, the New York legislature appointed Evarts to replace him, and he argued to uphold the decision. The Appellate Division affirmed the ruling, and Virginia again appealed. Evarts again represented the state in the New York Court of Appeals and again prevailed. The case generated widespread interest in both New York and the Southern states, and Evarts's arguments were reported in the daily press, as was nearly every step in the case. Thurlow Weed

Edward Thurlow Weed (November 15, 1797 – November 22, 1882) was a printer, New York newspaper publisher, and Whig and Republican politician. He was the principal political advisor to prominent New York politician William H. Seward and was ins ...

said that the quality of Evarts's arguments "placed beyond doubt his right to be ranked among the foremost lawyers of the country."

In 1856 Evarts represented the widow of Henry Parish, who was the proponent of his will and codicils in probate. His brothers contested the will on the grounds of incapacity and undue influence. (The brothers had been the decedent's executor in the will but, by a codicil executed after he was struck with paralysis that rendered him nearly speechless, they were removed.) The proceedings took on a ''Bleak House

''Bleak House'' is a novel by Charles Dickens, first published as a 20-episode serial between March 1852 and September 1853. The novel has many characters and several sub-plots, and is told partly by the novel's heroine, Esther Summerson, and ...

''-like life of its own (the Dickens novel having been published only three years before) with eminent counsel on all sides. The estate was worth over $1.5 million at the beginning of the trial. There were 111 days of testimony before the Surrogate and two weeks of oral argument before the case closed on November 23, 1857. The Surrogate admitted the will and the first codicil (removing the brothers as executors and bequeathing them the residue of the estate) but rejected the second and third (providing for $50,000 in charitable bequests). After four-and-a half years of appeal, involving two arguments before the Court of appeals the judgment was affirmed. The ''Times'' concluded: "The three volumes of evidence reveal a web of fact, experience and motive, rarely matched in works of fiction, and the three remaining volumes of briefs and arguments exhibit an array of learning, ingenuity and sustained ability, that will always place this suit in the front rank of the ''causes célèbres'' of American jurisprudence." As a result of this case his firm would be entrusted with many large estates, including that of the Astors

The Astor family achieved prominence in business, society, and politics in the United States and the United Kingdom during the 19th and 20th centuries. With ancestral roots in the Italian Alps region of Italy by way of Germany,

the Astors settled ...

.

The most fame Evarts ever received for a case, however, came in 1875 when he represented nationally famous clergyman Henry Ward Beecher

Henry Ward Beecher (June 24, 1813 – March 8, 1887) was an American Congregationalist clergyman, social reformer, and speaker, known for his support of the Abolitionism, abolition of slavery, his emphasis on God's love, and his 1875 adultery ...

in a suit for "unlawful conversation" (unlawful sexual intercourse) by Beecher with the wife of plaintiff Theodore Tilton

Theodore Tilton (October 2, 1835 – May 29, 1907) was an American newspaper editor, poet and abolitionist. He was born in New York City to Silas Tilton and Eusebia Tilton (same surname). On his twentieth birthday, October 2, 1855, he married ...

and the alienation of his wife's affections. The case was a national sensation, but despite what appeared to be clear evidence, Evarts obtained a hung jury for his client; in fact only three of the twelve jurors voted in favor of Tilton.

Evarts's courtroom style was summarized as follows: " s long sentences, which, in the period when he was most conspicuous in the public mind, were often marveled over, never seemed to impair the clarity of his arguments; the vein of humor he could infuse in the driest case, the logic and vigor of his utterances, the soundness of his information, the great thoroughness of his preparation, were all factors in his success. But, of course, these do not account altogether for his triumph as an advocate, which was largely due to his positive genius for that kind of work." Another observer described his style:

Early political career

Evarts early associated himself with the city's Whig interests dominated byThurlow Weed

Edward Thurlow Weed (November 15, 1797 – November 22, 1882) was a printer, New York newspaper publisher, and Whig and Republican politician. He was the principal political advisor to prominent New York politician William H. Seward and was ins ...

. In 1849 he received the appointment of assistant United States attorney for the district of New York. He served until 1853. In 1851 he was also made a commissioner of the Almshouse (later known as the Commissioners of Charity and Correction). The most famous case Evarts was involved in while district attorney was against the famous journalist John L. O'Sullivan

John Louis O'Sullivan (November 15, 1813 – March 24, 1895) was an American columnist, editor, and diplomat who used the term "manifest destiny" in 1845 to promote the annexation of Texas and the Oregon Country to the United States. O'Sullivan ...

and his fellow filibusters, who had fitted out the ''Cleopatra'' to aid an insurrection in Cuba. After a month-long trial, the jury was unable to come to a verdict.

Unlike other Northern Whigs, Evarts was not an abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

and defended the Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that defused a political confrontation between slave and free states on the status of territories acquired in the Mexican–Ame ...

drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas (April 23, 1813 – June 3, 1861) was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. A senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party for president in the 1860 presidential election, which wa ...

.William Maxwell Evarts''Encyclopedia.com''. Retrieved February 9, 2022. He was not involved in the antislavery crusade except for his involvement in the Lemmon Slave Case. Evarts never showed the talent or inclination for electoral politics, but he early became relied on by party leaders to perform oratorical or public ceremonial functions. In early 1852 he made two major addresses at large meetings for

Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the U.S. Secretary of State under Presidents William Henry Harrison, ...

's candidacy: one in March at the Metropolitan Hall and the other in June at Constitution Hall right before the Whig National Convention. Evarts's allegiance was out of touch not only with both the Northern and Southern factions of the Whigs but also with William H. Seward

William Henry Seward (May 16, 1801 – October 10, 1872) was an American politician who served as United States Secretary of State from 1861 to 1869, and earlier served as governor of New York and as a United States Senate, United States Senat ...

, who supported General Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as a general in the United States Army from 1814 to 1861, taking part in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the early s ...

.

Although most former Webster supporters belonged to the Whiggish-aligned, moderate wing of the Republican Party

The Republican Party in the United States includes several factions, or wings.

During the 19th century, Republican factions included the Half-Breeds, who supported civil service reform; the Radical Republicans, who advocated the immediate and t ...

and Senator William H. Seward

William Henry Seward (May 16, 1801 – October 10, 1872) was an American politician who served as United States Secretary of State from 1861 to 1869, and earlier served as governor of New York and as a United States Senate, United States Senat ...

on the staunchly abolitionist end, Evarts became an enthusiastic supporter of Seward. In 1860, he was chairman of the New York delegation to the Republican National Convention

The Republican National Convention (RNC) is a series of presidential nominating conventions held every four years since 1856 by the United States Republican Party. They are administered by the Republican National Committee. The goal of the Repu ...

in Chicago, where his oratory was at the disposal of the Senator, who most observers believed was a strong favorite for the nomination. James G. Blaine described the effects of those efforts on his audience:

Evarts placed Seward's name in nomination, and when it became apparent that Seward would not attain it, Evarts, on behalf of Seward, graciously moved the unanimous nomination of Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

.

In 1861 he ran against Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley (February 3, 1811 – November 29, 1872) was an American newspaper editor and publisher who was the founder and newspaper editor, editor of the ''New-York Tribune''. Long active in politics, he served briefly as a congressm ...

for the Senate seat vacated by Seward (who had become Lincoln's Secretary of State), but when neither could attain the requisite votes, the legislature settled on Ira Harris

Ira Harris (May 31, 1802December 2, 1875) was an American jurist and senator from New York. He was also a friend of Abraham Lincoln.

Life

Ira Harris was born in Charleston, New York on May 31, 1802. He grew up on a farm, and graduated from Unio ...

as a compromise.

In 1862, he was one of the lawyers who argued the Prize Cases

''Prize Cases'', 67 U.S. (2 Black) 635 (1863), was a case argued before the Supreme Court of the United States in 1862 during the American Civil War. The Supreme Court's decision declared the blockade of the Southern ports ordered by President ...

for the United States before the U.S. Supreme Court.

He served on New York's Union Defense Committee during the Civil War. He was a delegate to the New York state constitutional convention of 1867. At the constitutional convention he was a member of the standing committee on the preamble and bill of rights and the committee on the judiciary.

Service in the Johnson, Grant, and Hayes administrations

From 1865 to 1868, Evarts was on the team of lawyers prosecuting

From 1865 to 1868, Evarts was on the team of lawyers prosecuting Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the United States Senate and the House of Representatives as a ...

for treason. In 1868, he became counsel for U.S. President Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a Dem ...

during his impeachment trial. He delivered the closing argument for Johnson, and Johnson was acquitted, an event that seemed unlikely when the trial began.

Afterward, Evarts was appointed Attorney General following the Senate's refusal to reconfirm Henry Stanbery

Henry Stanbery (February 20, 1803 – June 26, 1881) was an American lawyer from Ohio. He was most notable for his service as Ohio's first Ohio Attorney General, attorney general from 1846 to 1851 and the United States Attorney General from 1866 ...

to the office, from which Stanbery had resigned in order to participate in Johnson's defense. Evarts served as United States Attorney General

The United States attorney general (AG) is the head of the United States Department of Justice, and is the chief law enforcement officer of the federal government of the United States. The attorney general serves as the principal advisor to the p ...

from July 1868 until March 1869.

In 1872 he was counsel for the United States before the tribunal of arbitration on the ''Alabama'' claims in Geneva, Switzerland. His oral argument helped the United States recover on its claims for the destruction of Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

military ships, commercial ships, and commercial cargo by the CSS ''Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

'' and other Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

ships which had been built in and sailed from British ports during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

.

Evarts was a founding member of the New York City Bar Association

The New York City Bar Association (City Bar), founded in 1870, is a voluntary association of lawyers and law students. Since 1896, the organization, formally known as the Association of the Bar of the City of New York, has been headquartered in a ...

. He served as its first president from 1870 to 1879, the longest tenure of any president.

Evarts served as counsel for President-elect

Evarts served as counsel for President-elect Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governor ...

before the Electoral Commission

An election commission is a body charged with overseeing the implementation of electioneering process of any country. The formal names of election commissions vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, and may be styled an electoral commission, a c ...

that resolved the disputed presidential election of 1876. During President Hayes's administration, he served as Secretary of State. Initially, Evarts did not act upon reports of corruption in the foreign service and supported actions against internal whistleblowers John Myers, Wiley Wells and later John Mosby. However, when President Grant continued to hear such complaints during his post-presidential around-the-world tour, and such were confirmed by internal troubleshooters DeB. Randolph Keim and former General turned consul to Japan Julius Stahel

Julius H. Stahel-Számwald (born Gyula Számwald; November 5, 1825 – December 4, 1912) was a Hungarian soldier who emigrated to the United States and became a Union general in the American Civil War. After the war, he served as a U.S. diplomat, ...

, Evarts began to clean house before the 1880 election. He ultimately secured the resignation of a favorite subordinate, Frederick W. Seward

Frederick William Seward (July 8, 1830 – April 25, 1915) was an American politician and member of the Republican Party who twice served as the Assistant Secretary of State. The son of United States Secretary of State William H. Seward, ...

, for shielding rascals, and then several consuls in the Far East, including George Seward, David Bailey

David Royston Bailey (born 2 January 1938) is an English photographer and director, most widely known for his fashion photography and portraiture, and role in shaping the image of the Swinging Sixties.

Early life

David Bailey was born at Wh ...

and David Sickels. In 1881, Evarts was a delegate to the International Monetary Conference The international monetary conferences were a series of assemblies held in the second half of the 19th century. They were held with a view to reaching agreement on matters relating to international relationships between national currency systems.

B ...

at Paris.

U.S. Senator

Evarts gained the support of state legislators in 1884 for US Senator from New York, and from 1885 to 1891 he served one term. While in Congress ( 49th, 50th and 51st Congresses), he served as chairman of the U.S. Senate Committee on the Library from 1887 to 1891. He was also a sponsor of theJudiciary Act of 1891

The Judiciary Act of 1891 ({{USStat, 26, 826), also known as the Evarts Act after its primary sponsor, Senator William M. Evarts, created the United States courts of appeals and reassigned the jurisdiction of most routine appeals from the United S ...

also known as the Evarts Act, which created the United States courts of appeals

The United States courts of appeals are the intermediate appellate courts of the United States federal judiciary. The courts of appeals are divided into 11 numbered circuits that cover geographic areas of the United States and hear appeals fr ...

. As an orator, Senator Evarts stood in the foremost rank, and some of his best speeches were published.

Chair of the American Committee for the Statue of Liberty

Evarts led the American fund-raising effort for the pedestal for theStatue of Liberty

The Statue of Liberty (''Liberty Enlightening the World''; French: ''La Liberté éclairant le monde'') is a List of colossal sculpture in situ, colossal neoclassical sculpture on Liberty Island in New York Harbor in New York City, in the U ...

, serving as the chairman of the American Committee. He spoke at its unveiling on October 28, 1886. His speech was entitled "The United Work of the Two Republics."

Taking a breath in the middle of his address, he was understood to have completed his speech. The signal was given, and Bartholdi, together with Richard Butler and David H. King Jr., whose firm built the pedestal and erected the statue, let the veil fall from her face. A 'huge shock of sound' erupted as a thunderous cacophony of salutes from steamer whistles, brass bands, and booming guns, together with clouds of smoke from the cannonade, engulfed the statue for the next half hour.

Retirement

Senator Evarts retired from public life in 1891 due to ill health. He was still a partner in his law practice in New York City, called Evarts, Southmoyd and Choate. He died in New York City on February 28, 1901 and was buried at Ascutney Cemetery inWindsor, Vermont

Windsor is a town in Windsor County, Vermont, United States. As the "Birthplace of Vermont", the town is where the Constitution of Vermont was adopted in 1777, thus marking the founding of the Vermont Republic, a sovereign state until 1791, when ...

.

Evarts owned numerous properties in Windsor, Vermont

Windsor is a town in Windsor County, Vermont, United States. As the "Birthplace of Vermont", the town is where the Constitution of Vermont was adopted in 1777, thus marking the founding of the Vermont Republic, a sovereign state until 1791, when ...

, including Evarts Pond and a group of historic homes often referred to as Evarts Estate. The homes included 26 Main Street in Windsor. Evarts purchased this house from John Skinner in the 1820s for $5,000; it was passed down to his daughter, Elizabeth Hoar Evarts Perkins, who left the house to family members, including her son Maxwell Perkins

William Maxwell Evarts "Max" Perkins (September 20, 1884 – June 17, 1947) was an American book editor, best remembered for discovering authors Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, and Thomas Wolfe.

Early life and e ...

. The house stayed in the family until 2005. 26 Main Street in Windsor, Vermont was later restored and reopened as Snapdragon Inn. Snapdragon Inn is open to the public and features a library that displays items related to the history of William M. Evarts and his extended family.

Extended family

William Evarts was a descendant of the English immigrant John Everts; the family settled inSalisbury, Connecticut

Salisbury () is a town situated in Litchfield County, Connecticut, United States. The town is the northwesternmost in the state of Connecticut; the Massachusetts-New York-Connecticut tri-state marker is located at the northwest corner of the town ...

in the 17th century.Malcolm Day Rudd, ''A Historical Sketch of Salisbury, Connecticut'' (New York: Sanford's, 1890), 5. Evarts was a member of the extended Baldwin, Hoar and Sherman families, which had many members in American politics.

Ebenezer R. Hoar

Ebenezer Rockwood Hoar (February 21, 1816 – January 31, 1895) was an American politician, lawyer, and jurist from Massachusetts. He served as U.S. Attorney General from 1869 to 1870, and was the first head of the newly created Department of Jus ...

, a first cousin of Evarts, was a U.S. Attorney General

The United States attorney general (AG) is the head of the United States Department of Justice, and is the chief law enforcement officer of the federal government of the United States. The attorney general serves as the principal advisor to the p ...

, Associate Justice of the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts

The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court (SJC) is the highest court in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Although the claim is disputed by the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, the SJC claims the distinction of being the oldest continuously functi ...

and representative in Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of a ...

. The two were best friends and shared similar professional pursuits and political beliefs. Each served, in succession, as United States Attorney General. Some of Evarts's other first cousins include U.S. Senator and Governor of Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its cap ...

Roger Sherman Baldwin

Roger Sherman Baldwin (January 4, 1793 – February 19, 1863) was an American politician who served as the 32nd Governor of Connecticut from 1844 to 1846 and a United States senator from 1847 to 1851. As a lawyer, his career was most notable ...

; U.S. Senator from Massachusetts (brother of Ebenezer R.) George F. Hoar

George Frisbie Hoar (August 29, 1826 – September 30, 1904) was an American attorney and politician who represented Massachusetts in the United States Senate from 1877 to 1904. He belonged to an extended family that became politically prominen ...

; and Sherman Day

Sherman Day (1806–1884) was born in New Haven, Connecticut and died in Berkeley, California. He attended Phillips Academy, Andover and graduated from Yale College, A.B., 1826, receiving the degree from his father, Jeremiah Day (1773–1867), w ...

, California state senator and founding trustee of the University of California

The University of California (UC) is a public land-grant research university system in the U.S. state of California. The system is composed of the campuses at Berkeley, Davis, Irvine, Los Angeles, Merced, Riverside, San Diego, San Francisco, ...

.

Son Allen Wardner Evarts graduated from Yale College

Yale College is the undergraduate college of Yale University. Founded in 1701, it is the original school of the university. Although other Yale schools were founded as early as 1810, all of Yale was officially known as Yale College until 1887, ...

in 1869. He supported the founding of Wolf's Head Society

Wolf's Head Society is a senior society at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. The society is one of the reputed "Big Three" societies at Yale, along with Skull and Bones and Scroll and Key. Active undergraduate membership is elected annual ...

, and was first president of its alumni association. He held the position for a total of 20 years over two separate terms. He was a law partner, corporate president, and trustee of Vassar College

Vassar College ( ) is a private liberal arts college in Poughkeepsie, New York, United States. Founded in 1861 by Matthew Vassar, it was the second degree-granting institution of higher education for women in the United States, closely follo ...

.

Son Maxwell Evarts

Maxwell Evarts (November 15, 1862October 7, 1913) was an American lawyer and politician.

Early life and education

Maxwell Evarts was born on November 15, 1862, in New York City, the youngest of the twelve children of Helen Minerva (Wardner) and ...

graduated from Yale College

Yale College is the undergraduate college of Yale University. Founded in 1701, it is the original school of the university. Although other Yale schools were founded as early as 1810, all of Yale was officially known as Yale College until 1887, ...

in 1884, where he was also a member of Skull and Bones

Skull and Bones, also known as The Order, Order 322 or The Brotherhood of Death, is an undergraduate senior secret student society at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. The oldest senior class society at the university, Skull and Bone ...

. He served as a New York City district attorney, and later as General Counsel for E. H. Harriman

Edward Henry Harriman (February 20, 1848 – September 9, 1909) was an American financier and railroad executive.

Early life

Harriman was born on February 20, 1848, in Hempstead, New York, the son of Orlando Harriman Sr., an Episcopal clergyman ...

, which later became the Union Pacific Railroad

The Union Pacific Railroad , legally Union Pacific Railroad Company and often called simply Union Pacific, is a freight-hauling railroad that operates 8,300 locomotives over routes in 23 U.S. states west of Chicago and New Orleans. Union Paci ...

. He was president of two Windsor, Vermont, banks, and the chief financial backer of the Gridley Automatic Lathe ''(manufactured by the Windsor Machine Co.)''. In politics, Maxwell served as a member of the Vermont House of Representatives

The Vermont House of Representatives is the lower house of the Vermont General Assembly, the state legislature of the U.S. state of Vermont. The House comprises 150 members, with each member representing around 4,100 citizens. Representatives ar ...

and was a Vermont State Fair

The Vermont State Fair is an annual state fair held in Rutland, Vermont at the Vermont State Fairgrounds. In the past, the event had taken place in early September, and lasted 9 to 10 days. In 2016, the dates were changed to a mid-August festival ...

Commissioner.

Grandson Maxwell E. Perkins became the noted editor of Charles Scribner's Sons and dealt with authors F. Scott Fitzgerald

Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald (September 24, 1896 – December 21, 1940) was an American novelist, essayist, and short story writer. He is best known for his novels depicting the flamboyance and excess of the Jazz Age—a term he popularize ...

, Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Miller Hemingway (July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer, and journalist. His economical and understated style—which he termed the iceberg theory—had a strong influence on 20th-century fic ...

, Thomas Wolfe

Thomas Clayton Wolfe (October 3, 1900 – September 15, 1938) was an American novelist of the early 20th century.

Wolfe wrote four lengthy novels as well as many short stories, dramatic works, and novellas. He is known for mixing highly origin ...

, Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings

Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings (August 8, 1896 – December 14, 1953)

accessed December 8, 2014. was an and James Jones. Great-nephew

First Part

''American Lawyer,'' Vol. 4, Issue 1 (January 1902), pp. 4–10

Second Part

''American Lawyer,'' Vol. 4, Issue 2 (February 1902), pp. 59–65. Retrieved March 24, 2016. * * * * Online via

William Maxwell Evarts

US Department of Justice

Evarts, William Maxwell from 1818 to 1901. Papers from 1849 to 1887

Harvard Law School Library * Chief Justice

Sherman Genealogy Including Families of Essex, Suffolk and Norfolk, England

By Thomas Townsend Sherman

at

Sherman-Hoar family

at

William Maxwell Evarts Letters, 1839–1905 (bulk 1839–1879) MS 235

held by Special Collection & Archives, Nimitz Library at the United States Naval Academy {{DEFAULTSORT:Evarts, William M. 1818 births 1901 deaths Andrew Johnson administration cabinet members Boston Latin School alumni Harvard Law School alumni Members of the defense counsel for the impeachment trial of Andrew Johnson New York (state) Republicans Politicians from Boston Presidents of the New York City Bar Association Republican Party United States senators from New York (state) United States Attorneys General 1876 United States presidential election United States Secretaries of State Yale University alumni Yale College alumni Hayes administration cabinet members 19th-century American politicians Burials in Vermont New York (state) Whigs Lawyers from Boston Civil service reform in the United States Half-Breeds (Republican Party)

accessed December 8, 2014. was an and James Jones. Great-nephew

Evarts Boutell Greene

Evarts Boutell Greene (1870–1947) was an American historian, born in Kobe, Japan, where his parents were missionaries. He graduated Harvard University (B.A., 1890; Ph.D., 1893), and began teaching American history (1894) at the University of Ill ...

became a historian and was appointed Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

's first De Witt Clinton

DeWitt Clinton (March 2, 1769February 11, 1828) was an American politician and naturalist. He served as a United States senator, as the mayor of New York City, and as the seventh governor of New York. In this last capacity, he was largely resp ...

Professor of History in 1923 and department chairman from 1926 to 1939. He was chairman of the Columbia Institute of Japanese Studies 1936–1939. He was a noted authority on the American Colonial and Revolutionary War periods.

Another relative, Henry Sherman Boutell

Henry Sherman Boutell (March 14, 1856 – March 11, 1926) was an American lawyer and diplomat.

Biography

Boutell was born at Boston, Massachusetts, the son of Lewis Henry and Anna (Greene) Boutell. A colonial ancestry entitled him to membersh ...

, was a member of the Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolita ...

State House of Representatives in 1884, a member of the U.S. House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

from Illinois from 1897 to 1911 (6th District 1897–1903; 9th District 1903–1911), a delegate to the Republican National Convention

The Republican National Convention (RNC) is a series of presidential nominating conventions held every four years since 1856 by the United States Republican Party. They are administered by the Republican National Committee. The goal of the Repu ...

from Illinois in 1908 and U.S. Minister to Switzerland from 1911 to 1913.

Great-great-nephew Roger Sherman Greene II Roger Sherman Greene (1881–1947) was a diplomat, foundation official, medical administrator in China and a national leader in affairs relating to East Asia. He was the fourth son and sixth of eight children of Rev. Daniel Crosby Greene, a Con ...

, the son of Daniel Crosby Greene and Mary Jane (Forbes) Greene, was the U.S. Vice Consul in Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro ( , , ; literally 'River of January'), or simply Rio, is the capital of the state of the same name, Brazil's third-most populous state, and the second-most populous city in Brazil, after São Paulo. Listed by the GaWC as a b ...

in 1903–1904, in Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hidden Christian Sites in the ...

in 1904–1905 and in Kobe

Kobe ( , ; officially , ) is the capital city of Hyōgo Prefecture Japan. With a population around 1.5 million, Kobe is Japan's seventh-largest city and the third-largest port city after Tokyo and Yokohama. It is located in Kansai region, whic ...

in 1905; U.S. Consul in Vladivostok

Vladivostok ( rus, Владивосто́к, a=Владивосток.ogg, p=vɫədʲɪvɐˈstok) is the largest city and the administrative center of Primorsky Krai, Russia. The city is located around the Zolotoy Rog, Golden Horn Bay on the Sea ...

in 1907 and in Harbin

Harbin (; mnc, , v=Halbin; ) is a sub-provincial city and the provincial capital and the largest city of Heilongjiang province, People's Republic of China, as well as the second largest city by urban population after Shenyang and largest ...

1909–11; and U.S. Consul General in Hankow

Hankou, alternately romanized as Hankow (), was one of the three towns (the other two were Wuchang and Hanyang) merged to become modern-day Wuhan city, the capital of the Hubei province, China. It stands north of the Han and Yangtze Rivers whe ...

, 1911–1914.

Great-great-nephew Jerome Davis Greene

Jerome Davis Greene (October 12, 1874March 29, 1959) was an American banker and a trustee to several major organizations and trusts including the Brookings Institution and the Rockefeller Foundation.

Family

Greene was born in Yokohama, Japan ...

(1874–1959) was president of Lee, Higginson & Company 1917–1932; secretary, Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

Corporation, 1905–1910 and 1934–43; general manager of the Rockefeller Institute 1910–1912; assistant and secretary to John D. Rockefeller Jr.

John Davison Rockefeller Jr. (January 29, 1874 – May 11, 1960) was an American financier and philanthropist, and the only son of Standard Oil co-founder John D. Rockefeller.

He was involved in the development of the vast office complex in M ...

as trustee of the Rockefeller Institute; trustee of the Rockefeller Foundation

The Rockefeller Foundation is an American private foundation and philanthropic medical research and arts funding organization based at 420 Fifth Avenue, New York City. The second-oldest major philanthropic institution in America, after the Carneg ...

; trustee of the Rockefeller General Education Board 1910–1939; executive secretary, American Section, Allied Maritime Transport Council, in 1918; Joint Secretary of the Reparations, Paris Peace Conference, in 1919; chairman, American Council Institute of Pacific Relations, 1929–1932; trustee of the Brookings Institution

The Brookings Institution, often stylized as simply Brookings, is an American research group founded in 1916. Located on Think Tank Row in Washington, D.C., the organization conducts research and education in the social sciences, primarily in ec ...

of Washington, 1928–1945; and a founding member of the Council on Foreign Relations

The Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) is an American think tank

A think tank, or policy institute, is a research institute that performs research and advocacy concerning topics such as social policy, political strategy, economics, mi ...

.

Great-grandson Archibald Cox

Archibald Cox Jr. (May 17, 1912 – May 29, 2004) was an American lawyer and law professor who served as U.S. Solicitor General under President John F. Kennedy and as a special prosecutor during the Watergate scandal. During his career, he was a p ...

served as a U.S. Solicitor General and special prosecutor during President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

's Watergate scandal

The Watergate scandal was a major political scandal in the United States involving the administration of President Richard Nixon from 1972 to 1974 that led to Nixon's resignation. The scandal stemmed from the Nixon administration's continual ...

, whereas Evarts defended a U.S. President (Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a Dem ...

) in his impeachment trial. In a sense, they both successfully argued their cases, which represent two of the four U.S. Presidential impeachment efforts. An impeachment trial was not held in Nixon's case: Nixon resigned before the House of Representatives acted on the House Judiciary Committee's recommendation that Nixon be impeached.

Legacy

A eulogist summarized his career thus:Mr. Evarts's most conspicuous, perhaps sole, title to fame is, that he was a great lawyer and brilliant advocate. ... his study of legal principles was profound, his acquaintance with literature was wide, his ideas of professional ethics were exalted. He held great National offices, but his title to them was rather as lawyer than statesman.On March 6, 1943, construction began on a

United States Maritime Service

The United States Maritime Service (USMS) was established in 1938 under the provisions of the Merchant Marine Act of 1936 as voluntary training organization to train individuals to become officers and crewmembers on merchant ships that form the U ...

liberty ship

Liberty ships were a class of cargo ship built in the United States during World War II under the Emergency Shipbuilding Program. Though British in concept, the design was adopted by the United States for its simple, low-cost construction. Mass ...

in Evarts's name. The SS ''William M. Evarts'' (hull identification number MS 1038) was launched April 22, 1943, and served during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

in the European theater. It transported troops and supplies from its home port in Norfolk, Virginia

Norfolk ( ) is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. Incorporated in 1705, it had a population of 238,005 at the 2020 census, making it the third-most populous city in Virginia after neighboring Virginia Be ...

to various ports on the Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts. After World War II, the ship was decommissioned and finally scrapped in 1961.

See also

* List of Skull and Bones MembersNotes

Sources

* * * * Online viaHeinonline.org

HeinOnline (HOL) is a commercial internet database service launched in 2000 by William S. Hein & Co., Inc. (WSH Co), a Buffalo, New York publisher specializing in legal materials. The company began in Buffalo, New York, in 1961 and is currently b ...

(subscription required)First Part

''American Lawyer,'' Vol. 4, Issue 1 (January 1902), pp. 4–10

Second Part

''American Lawyer,'' Vol. 4, Issue 2 (February 1902), pp. 59–65. Retrieved March 24, 2016. * * * * Online via

Heinonline.org

HeinOnline (HOL) is a commercial internet database service launched in 2000 by William S. Hein & Co., Inc. (WSH Co), a Buffalo, New York publisher specializing in legal materials. The company began in Buffalo, New York, in 1961 and is currently b ...

(subscription required). Reprinted from the ''New York Mail & Express''.

Further reading

* Sherman Evarts (editor/introduction), ''Arguments and Speeches of William Maxwell Evarts. In Three Volumes.'' Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1919.External links

* * * * *William Maxwell Evarts

US Department of Justice

Evarts, William Maxwell from 1818 to 1901. Papers from 1849 to 1887

Harvard Law School Library * Chief Justice

Salmon P. Chase

Salmon Portland Chase (January 13, 1808May 7, 1873) was an American politician and jurist who served as the sixth chief justice of the United States. He also served as the 23rd governor of Ohio, represented Ohio in the United States Senate, a ...

Sherman Genealogy Including Families of Essex, Suffolk and Norfolk, England

By Thomas Townsend Sherman

at

Political Graveyard

The Political Graveyard is a website and database that catalogues information on more than 277,000 American political figures and political families, along with other information. The name comes from the website's inclusion of burial locations of ...

Sherman-Hoar family

at

Political Graveyard

The Political Graveyard is a website and database that catalogues information on more than 277,000 American political figures and political families, along with other information. The name comes from the website's inclusion of burial locations of ...

William Maxwell Evarts Letters, 1839–1905 (bulk 1839–1879) MS 235

held by Special Collection & Archives, Nimitz Library at the United States Naval Academy {{DEFAULTSORT:Evarts, William M. 1818 births 1901 deaths Andrew Johnson administration cabinet members Boston Latin School alumni Harvard Law School alumni Members of the defense counsel for the impeachment trial of Andrew Johnson New York (state) Republicans Politicians from Boston Presidents of the New York City Bar Association Republican Party United States senators from New York (state) United States Attorneys General 1876 United States presidential election United States Secretaries of State Yale University alumni Yale College alumni Hayes administration cabinet members 19th-century American politicians Burials in Vermont New York (state) Whigs Lawyers from Boston Civil service reform in the United States Half-Breeds (Republican Party)