William Lloyd Garrison on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

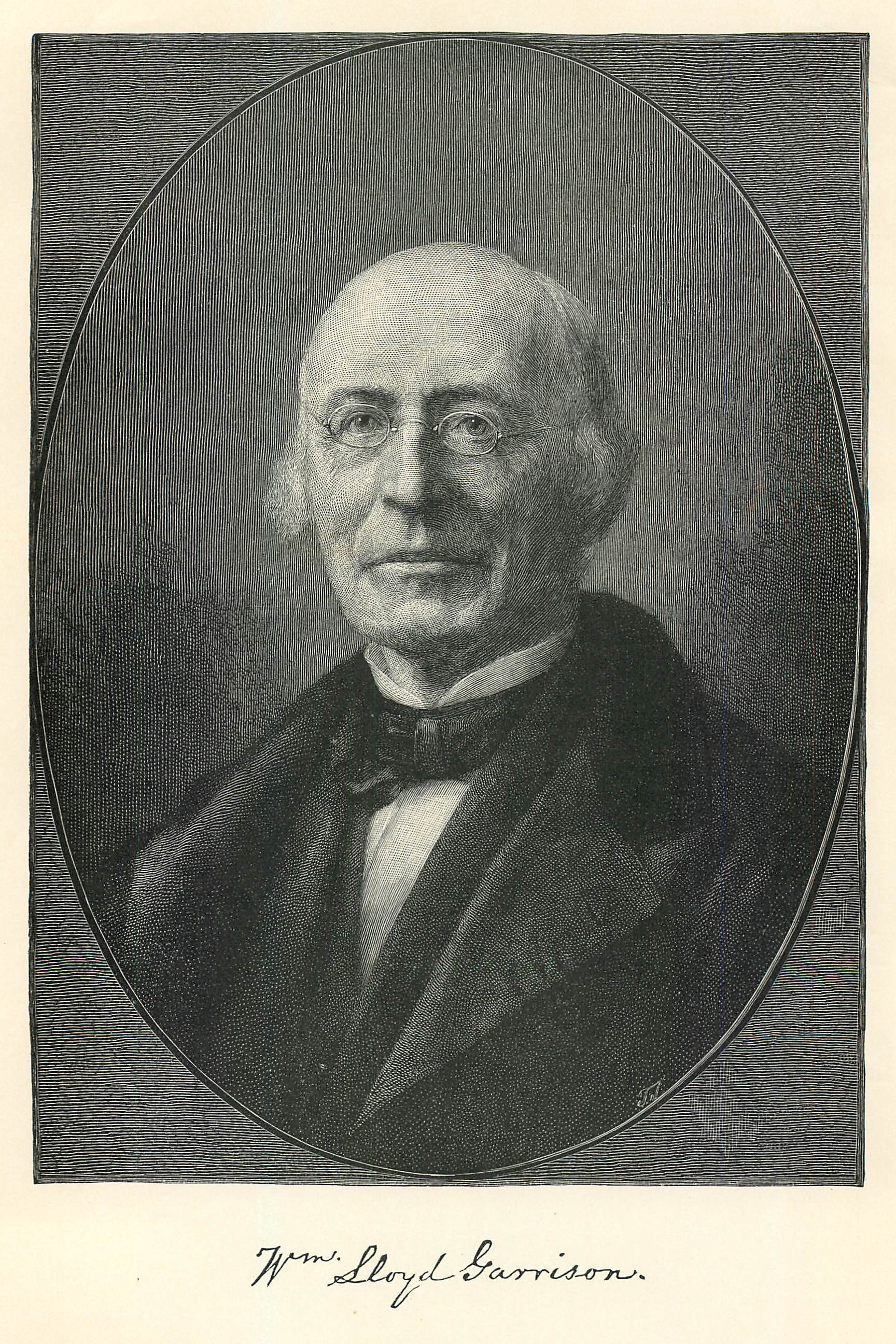

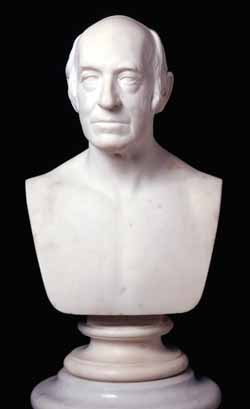

William Lloyd Garrison (December , 1805 – May 24, 1879) was a prominent American

Garrison was born on December 10, 1805, in Newburyport, Massachusetts, the son of immigrants from the British colony of

Garrison was born on December 10, 1805, in Newburyport, Massachusetts, the son of immigrants from the British colony of

In 1829, Garrison began writing for and became co-editor with Benjamin Lundy of the

In 1829, Garrison began writing for and became co-editor with Benjamin Lundy of the

Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words '' Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρ ...

, abolitionist, journalist, suffragist, and social reformer. He is best known for his widely read antislavery newspaper ''The Liberator

Liberator or The Liberators or ''variation'', may refer to:

Literature

* ''Liberators'' (novel), a 2009 novel by James Wesley Rawles

* ''The Liberators'' (Suvorov book), a 1981 book by Victor Suvorov

* ''The Liberators'' (comic book), a Britis ...

'', which he founded in 1831 and published in Boston until slavery in the United States was abolished by constitutional amendment in 1865. Garrison promoted "no-governmentism" and rejected the inherent validity of the American government on the basis that its engagement in war, imperialism, and slavery made it corrupt and tyrannical. He initially opposed violence as a principle and advocated for Christian nonresistance

Christian pacifism is the theological and ethical position according to which pacifism and non-violence have both a scriptural and rational basis for Christians, and affirms that any form of violence is incompatible with the Christian faith. Chr ...

against evil; at the outbreak of the Civil War, he abandoned his previous principles and embraced the armed struggle and the Lincoln administration. He was one of the founders of the American Anti-Slavery Society and promoted immediate and uncompensated, as opposed to gradual and compensated, emancipation of slaves in the United States

The legal institution of human chattel slavery, comprising the enslavement primarily of Africans and African Americans, was prevalent in the United States of America from its founding in 1776 until 1865, predominantly in the South. Slaver ...

.

Garrison was a typesetter and could run a printing shop; he wrote his editorials in ''The Liberator'' while setting them in type, without writing them out first on paper. This helped assure the viability of ''The Liberator'' and also that it contained exactly what Garrison wanted, as he did not have to deal with any outsiders to produce his paper, except his partner Isaac Knapp. Like the other major abolitionist printer-publisher, the martyred Elijah Lovejoy, a price was on his head; he was burned in effigy and a gallows was erected in front of his Boston office. While he was relatively safe in Boston, at one point he had to be smuggled onto a ship to escape to England, where he remained for a year.

Garrison also emerged as a leading advocate of women's rights, which prompted a split in the abolitionist community. In the 1870s, Garrison became a prominent voice for the women's suffrage movement

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

.

Early life and education

Garrison was born on December 10, 1805, in Newburyport, Massachusetts, the son of immigrants from the British colony of

Garrison was born on December 10, 1805, in Newburyport, Massachusetts, the son of immigrants from the British colony of New Brunswick

New Brunswick (french: Nouveau-Brunswick, , locally ) is one of the thirteen Provinces and territories of Canada, provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime Canada, Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic Canad ...

, in present-day Canada. Under An Act for the relief of sick and disabled seamen, his father Abijah Garrison, a merchant sailing pilot and master, had obtained American papers and moved his family to Newburyport in 1806. The U.S. Embargo Act of 1807, intended to injure Great Britain, caused a decline in American commercial shipping. The elder Garrison became unemployed and deserted the family in 1808. Garrison's mother was Frances Maria Lloyd, reported to have been tall, charming, and of a strong religious character. She started referring to their son William as Lloyd, his middle name, to preserve her family name; he later printed his name as "Wm. Lloyd". She died in 1823, in the city of Baltimore, Maryland

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

.

Garrison sold homemade lemonade and candy as a youth, and also delivered wood to help support the family. In 1818, at 13, Garrison began working as an apprentice compositor for the '' Newburyport Herald.'' He soon began writing articles, often under the pseudonym ''Aristides

Aristides ( ; grc-gre, Ἀριστείδης, Aristeídēs, ; 530–468 BC) was an ancient Athenian statesman. Nicknamed "the Just" (δίκαιος, ''dikaios''), he flourished in the early quarter of Athens' Classical period and is remembe ...

.'' (Aristides was an Athenian statesman and general, nicknamed "the Just".) He could write as he typeset his writing, without the need for paper. After his apprenticeship ended, Garrison became the sole owner, editor, and printer of the ''Newburyport Free Press,'' acquiring the rights from his friend Isaac Knapp, who had also apprenticed at the ''Herald''. One of their regular contributors was poet and abolitionist John Greenleaf Whittier

John Greenleaf Whittier (December 17, 1807 – September 7, 1892) was an American Quaker poet and advocate of the abolition of slavery in the United States. Frequently listed as one of the fireside poets, he was influenced by the Scottish poet R ...

. In this early work as a small-town newspaper writer, Garrison acquired skills he would later use as a nationally known writer, speaker, and newspaper publisher. In 1828, he was appointed editor of the ''National Philanthropist'' in Boston, Massachusetts, the first American journal to promote legally-mandated temperance.

He became involved in the anti-slavery movement in the 1820s, and over time he rejected both the American Colonization Society and the gradualist views of most others involved in the movement. Garrison co-founded ''The Liberator'' to espouse his abolitionist views, and in 1832 he organized out of its readers the New-England Anti-Slavery Society

The Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, headquartered in Boston, was organized as an auxiliary of the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1835. Its roots were in the New England Anti-Slavery Society, organized by William Lloyd Garrison, editor of ' ...

. This society expanded into the American Anti-Slavery Society, which espoused the position that slavery should be immediately abolished.

Career

Reformer

At the age of 25, Garrison joined the anti-slavery movement, later crediting the 1826 book of Presbyterian Reverend John Rankin, ''Letters on Slavery'', for attracting him to the cause. For a brief time, he became associated with the American Colonization Society, an organization that promoted the "resettlement" of free blacks to a territory (now known asLiberia

Liberia (), officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to its northwest, Guinea to its north, Ivory Coast to its east, and the Atlantic Ocean to its south and southwest. It ...

) on the west coast of Africa. Although some members of the society encouraged granting freedom to slaves, others considered relocation a means to reduce the number of already free blacks in the United States. Southern members thought reducing the threat of free blacks in society would help preserve the institution of slavery. By late 1829–1830, "Garrison rejected colonization, publicly apologized for his error, and then, as was typical of him, he censured all who were committed to it." He stated that this opinion was shaped by fellow abolitionist William J. Watkins, a Black educator and anti-colonizationist.

''Genius of Universal Emancipation''

In 1829, Garrison began writing for and became co-editor with Benjamin Lundy of the

In 1829, Garrison began writing for and became co-editor with Benjamin Lundy of the Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belie ...

newspaper '' Genius of Universal Emancipation'', published at that time in Baltimore, Maryland

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

. With his experience as a printer and newspaper editor, Garrison changed the layout of the paper and handled other production issues. Lundy was freed to spend more time touring as an anti-slavery speaker. Garrison initially shared Lundy's gradualist views, but while working for the ''Genius'', he became convinced of the need to demand immediate and complete emancipation. Lundy and Garrison continued to work together on the paper despite their differing views. Each signed his editorials.

Garrison introduced "The Black List," a column devoted to printing short reports of "the barbarities of slaverykidnappings, whippings, murders." For instance, Garrison reported that Francis Todd, a shipper from Garrison's home town of Newburyport, Massachusetts, was involved in the domestic slave trade, and that he had recently had slaves shipped from Baltimore to New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

coastwise trade on his ship the ''Francis''. (This was completely legal. An expanded domestic trade, "breeding" slaves in Maryland and Virginia for shipment south, replaced the importation of African slaves, prohibited in 1808; see Slavery in the United States#Slave trade.)

Todd filed a suit for libel in Maryland against both Garrison and Lundy; he thought to gain support from pro-slavery courts. The state of Maryland also brought criminal charges against Garrison, quickly finding him guilty and ordering him to pay a fine of $50 and court costs. (Charges against Lundy were dropped because he had been traveling when the story was printed.) Garrison refused to pay the fine and was sentenced to a jail term of six months. He was released after seven weeks when the anti-slavery philanthropist Arthur Tappan paid his fine. Garrison decided to leave Maryland, and he and Lundy amicably parted ways.

The threat posed by anti-slavery organizations and their activity drew violent reactions from slave interests in both the Southern and Northern states, with mobs breaking up anti-slavery meetings, assaulting lecturers, ransacking anti-slavery offices, burning postal sacks of anti-slavery pamphlets, and destroying anti-slavery presses. Healthy bounties were offered in Southern states for the capture of Garrison, "dead or alive".

On October 21, 1835, "an assemblage of fifteen hundred or two thousand highly respectable gentlemen", as they were described in the '' Boston Commercial Gazette'', surrounded the building housing Boston's anti-slavery offices, where Garrison had agreed to address a meeting of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society after the fiery British abolitionist George Thompson was unable to keep his engagement with them. Mayor Theodore Lyman persuaded the women to leave the building, but when the mob learned that Thompson was not within, they began yelling for Garrison. Lyman was a staunch anti-abolitionist but wanted to avoid bloodshed and suggested Garrison escape by a back window while Lyman told the crowd Garrison was gone. The mob spotted and apprehended Garrison, tied a rope around his waist, and pulled him through the streets towards Boston Common, calling for

The threat posed by anti-slavery organizations and their activity drew violent reactions from slave interests in both the Southern and Northern states, with mobs breaking up anti-slavery meetings, assaulting lecturers, ransacking anti-slavery offices, burning postal sacks of anti-slavery pamphlets, and destroying anti-slavery presses. Healthy bounties were offered in Southern states for the capture of Garrison, "dead or alive".

On October 21, 1835, "an assemblage of fifteen hundred or two thousand highly respectable gentlemen", as they were described in the '' Boston Commercial Gazette'', surrounded the building housing Boston's anti-slavery offices, where Garrison had agreed to address a meeting of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society after the fiery British abolitionist George Thompson was unable to keep his engagement with them. Mayor Theodore Lyman persuaded the women to leave the building, but when the mob learned that Thompson was not within, they began yelling for Garrison. Lyman was a staunch anti-abolitionist but wanted to avoid bloodshed and suggested Garrison escape by a back window while Lyman told the crowd Garrison was gone. The mob spotted and apprehended Garrison, tied a rope around his waist, and pulled him through the streets towards Boston Common, calling for

Garrison's appeal for women's mass petitioning against slavery sparked controversy over women's right to a political voice. In 1837, women abolitionists from seven states convened in New York to expand their petitioning efforts and repudiate the social mores that proscribed their participation in public affairs. That summer, sisters Angelina Grimké and Sarah Grimké responded to the controversy aroused by their public speaking with treatises on woman's rightsAngelina's "Letters to Catherine E. Beecher" and Sarah's "Letters on the Equality of the Sexes and Condition of Woman"and Garrison published them first in ''The Liberator'' and then in book form. Instead of surrendering to appeals for him to retreat on the "woman question," Garrison announced in December 1837 that ''The Liberator'' would support "the rights of woman to their utmost extent." The Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society appointed women to leadership positions and hired Abby Kelley as the first of several female field agents.

In 1840, Garrison's promotion of woman's rights within the anti-slavery movement was one of the issues that caused some abolitionists, including New York brothers Arthur Tappan and Lewis Tappan, to leave the AAS and form the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, which did not admit women. In June of that same year, when the World Anti-Slavery Convention meeting in London refused to seat America's women delegates, Garrison, Charles Lenox Remond,

Garrison's appeal for women's mass petitioning against slavery sparked controversy over women's right to a political voice. In 1837, women abolitionists from seven states convened in New York to expand their petitioning efforts and repudiate the social mores that proscribed their participation in public affairs. That summer, sisters Angelina Grimké and Sarah Grimké responded to the controversy aroused by their public speaking with treatises on woman's rightsAngelina's "Letters to Catherine E. Beecher" and Sarah's "Letters on the Equality of the Sexes and Condition of Woman"and Garrison published them first in ''The Liberator'' and then in book form. Instead of surrendering to appeals for him to retreat on the "woman question," Garrison announced in December 1837 that ''The Liberator'' would support "the rights of woman to their utmost extent." The Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society appointed women to leadership positions and hired Abby Kelley as the first of several female field agents.

In 1840, Garrison's promotion of woman's rights within the anti-slavery movement was one of the issues that caused some abolitionists, including New York brothers Arthur Tappan and Lewis Tappan, to leave the AAS and form the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, which did not admit women. In June of that same year, when the World Anti-Slavery Convention meeting in London refused to seat America's women delegates, Garrison, Charles Lenox Remond,  Although Henry Stanton had cooperated in the Tappans' failed attempt to wrest leadership of the AAS from Garrison, he was part of another group of abolitionists unhappy with Garrison's influencethose who disagreed with Garrison's insistence that because the U.S. Constitution was a pro-slavery document, abolitionists should not participate in politics and government. A growing number of abolitionists, including Stanton, Gerrit Smith, Charles Turner Torrey, and Amos A. Phelps, wanted to form an anti-slavery political party and seek a political solution to slavery. They withdrew from the AAS in 1840, formed the Liberty Party, and nominated

Although Henry Stanton had cooperated in the Tappans' failed attempt to wrest leadership of the AAS from Garrison, he was part of another group of abolitionists unhappy with Garrison's influencethose who disagreed with Garrison's insistence that because the U.S. Constitution was a pro-slavery document, abolitionists should not participate in politics and government. A growing number of abolitionists, including Stanton, Gerrit Smith, Charles Turner Torrey, and Amos A. Phelps, wanted to form an anti-slavery political party and seek a political solution to slavery. They withdrew from the AAS in 1840, formed the Liberty Party, and nominated

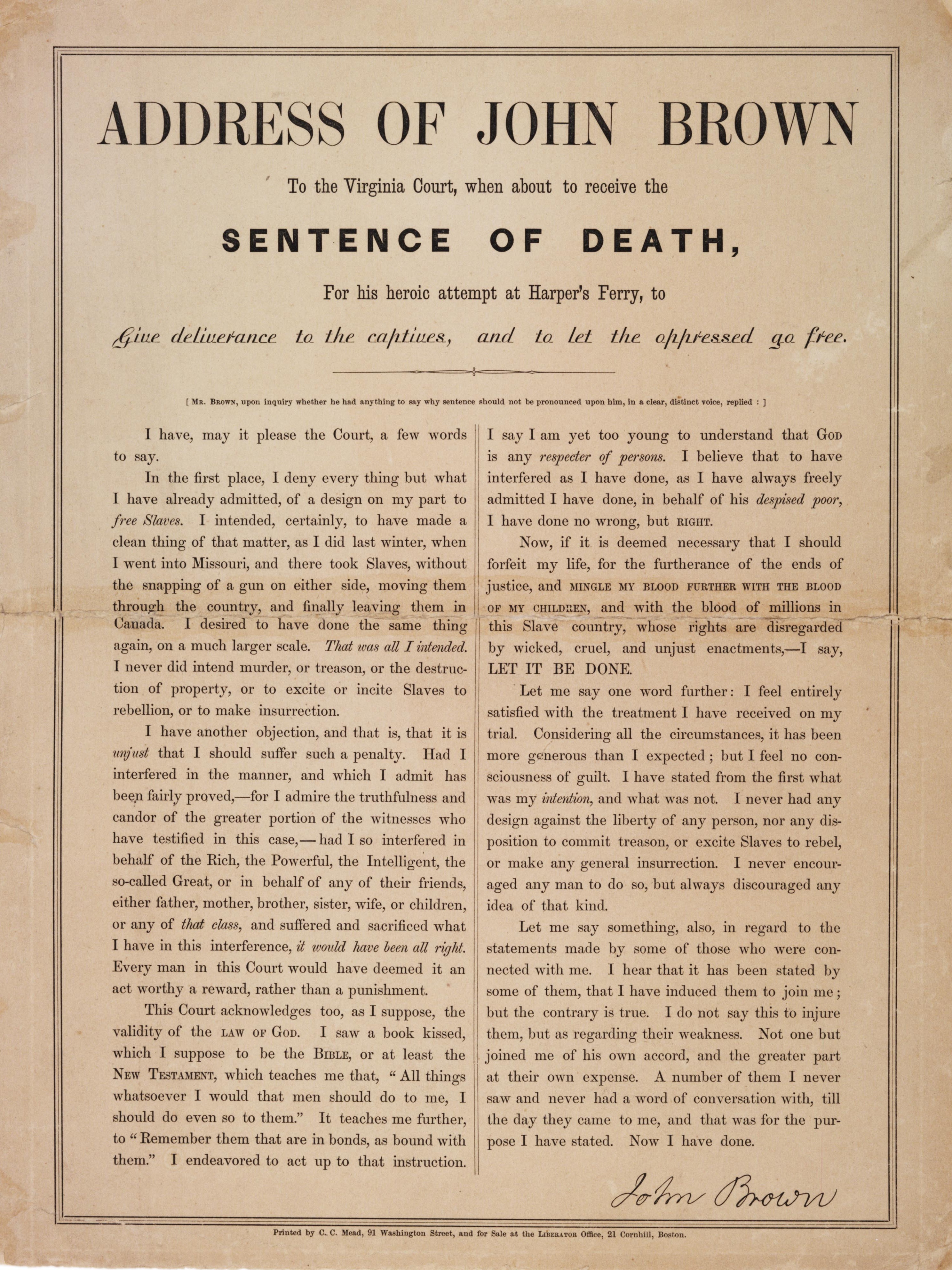

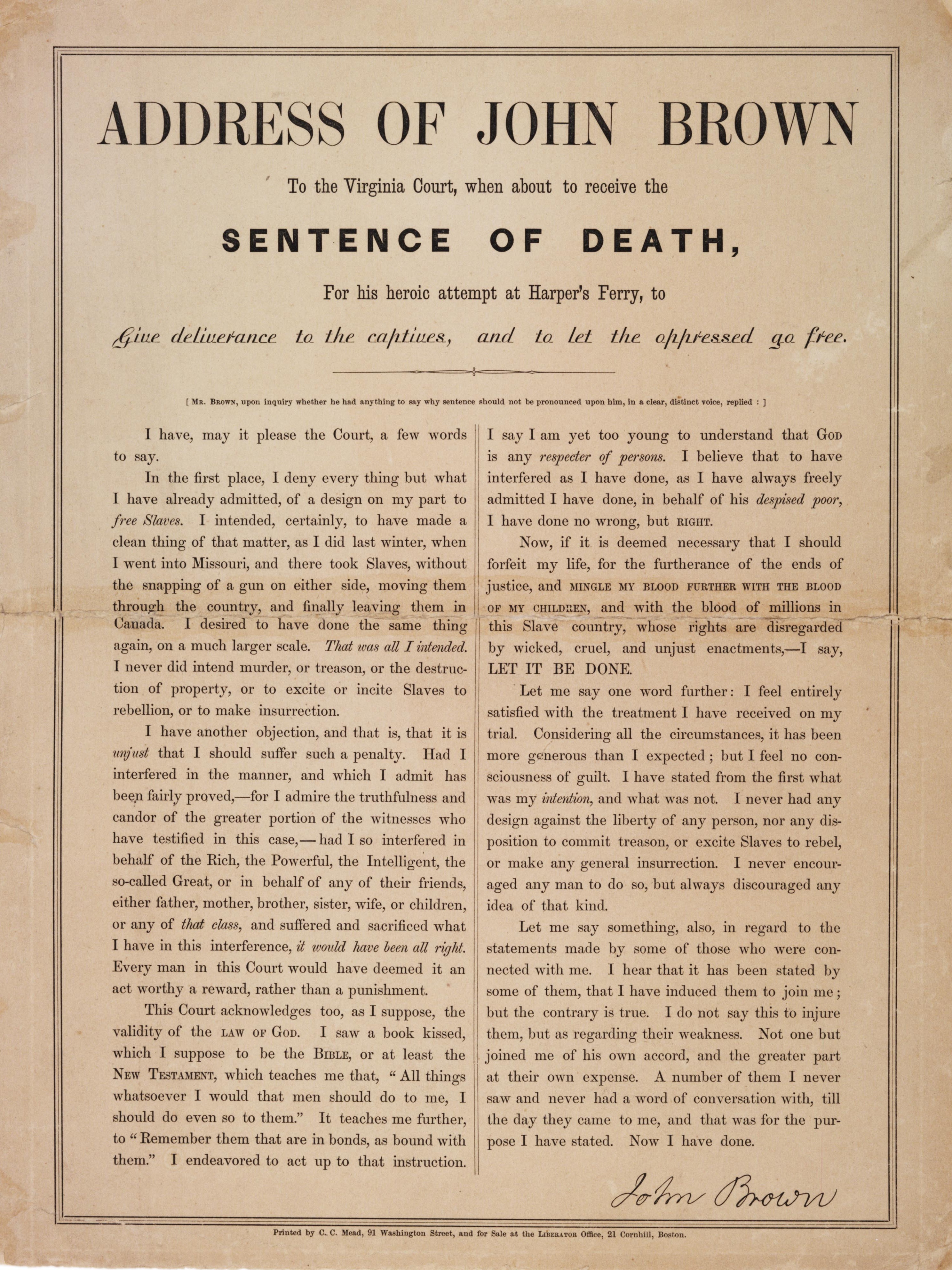

The events in John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, followed by Brown's trial and execution, were closely followed in ''The Liberator''. Garrison had Brown's last speech, in court, printed as a broadside, available in the ''Liberator'' office.

The events in John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, followed by Brown's trial and execution, were closely followed in ''The Liberator''. Garrison had Brown's last speech, in court, printed as a broadside, available in the ''Liberator'' office.

Garrison's outspoken anti-slavery views repeatedly put him in danger. Besides his imprisonment in Baltimore and the price placed on his head by the state of

Garrison's outspoken anti-slavery views repeatedly put him in danger. Besides his imprisonment in Baltimore and the price placed on his head by the state of

Garrison spent more time at home with his family. He wrote weekly letters to his children and cared for his increasingly ill wife, Helen. She had suffered a small stroke on December 30, 1863, and was increasingly confined to the house. Helen died on January 25, 1876, after a severe cold worsened into

Garrison spent more time at home with his family. He wrote weekly letters to his children and cared for his increasingly ill wife, Helen. She had suffered a small stroke on December 30, 1863, and was increasingly confined to the house. Helen died on January 25, 1876, after a severe cold worsened into  Suffering from kidney disease, Garrison continued to weaken during April 1879. He moved to New York to live with his daughter Fanny's family. In late May, his condition worsened, and his five surviving children rushed to join him. Fanny asked if he would enjoy singing some hymns. Although he was unable to sing, his children sang favorite hymns while he beat time with his hands and feet. On May 24, 1879, Garrison lost consciousness and died just before midnight.

Garrison was buried in the Forest Hills Cemetery in Boston's Jamaica Plain neighborhood on May 28, 1879. At the public memorial service, eulogies were given by Theodore Dwight Weld and Wendell Phillips. Eight abolitionist friends, both white and black, served as his pallbearers. Flags were flown at half-staff all across

Suffering from kidney disease, Garrison continued to weaken during April 1879. He moved to New York to live with his daughter Fanny's family. In late May, his condition worsened, and his five surviving children rushed to join him. Fanny asked if he would enjoy singing some hymns. Although he was unable to sing, his children sang favorite hymns while he beat time with his hands and feet. On May 24, 1879, Garrison lost consciousness and died just before midnight.

Garrison was buried in the Forest Hills Cemetery in Boston's Jamaica Plain neighborhood on May 28, 1879. At the public memorial service, eulogies were given by Theodore Dwight Weld and Wendell Phillips. Eight abolitionist friends, both white and black, served as his pallbearers. Flags were flown at half-staff all across

Address at Park Street Church, Boston, July 4, 1829

(Garrison's first major public statement; an extensive statement of egalitarian principle). *

"Address to the Colonization Society"

(a slightly abridged version of the address July 4, 1829).

The Liberator, January 1, 1831 – December 29, 1865

. *

(Garrison's introductory column for ''The Liberator'', – January 1, 1831). *

Truisms

(''The Liberator'', January 8, 1831). *

The Insurrection

(Garrison's reaction to news of Nat Turner's rebellion, – ''The Liberator'', September 3, 1831). *

On the Constitution and the Union

(''The Liberator'', December 29, 1832). *

Abolition at the Ballot Box

(''The Liberator'', June 28, 1839). *

The American Union

(''The Liberator'', January 10, 1845). ** (September 24, 1855). *

The Tragedy at Harper's Ferry

, (''The Liberator'', October 28, 1859). *

John Brown and the Principle of Nonresistance

(Speech in the Tremont Temple, Boston, December 2, 1859, – the day Brown was hanged – ''The Liberator'', December 16, 1859). *

The War – Its Cause and Cure

(''The Liberator'', May 3, 1861). *

Valedictory: The Final Number of ''The Liberator''

(''The Liberator'', December 29, 1865).

The Liberator Files

(Horace Seldon's summary of research of Garrison's ''The Liberator'')

Declaration of Sentiments of the Nationale Anti-Slavery Convention

(December 1833, Philadelphia)

Declaration of Sentiments of The New England Non-Resistance Society

(''The Liberator'', September 28, 1838).

William Lloyd Garrison works

(Cornell University Library Samuel J. May Anti-Slavery Collection)

William Lloyd Garrison works

(Cornell University Digital Library Collections).

William Lloyd Garrison on non-resistance : together with a personal sketch by his daughter Fanny Garrison Villard and a tribute by Leo Tolstoy

Reading Garrison's Letters

(Horace Seldon's insight into the thought, work and life of Garrison, – based on "Letters of William Lloyd Garrison", Belknap Press of Harvard University, W. M. Merrill and L. Ruchames Editors).

The Liberator: William Lloyd Garrison, A Biography

(Boston; Little, Brown, 1963).

William Lloyd Garrison profile

on Spartacus Educational

''The Liberator Files'' online

Report of the Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice

*

William Lloyd Garrison

and

Who is William Lloyd Garrison?

– American Experience, PBS *

William Lloyd Garrison: Words of Thunder

" WGBH Forum

PBS Teachers Resources: William Lloyd Garrison 1805–1879

* The story of his life is retold in the radio drama

The Liberators (Part I)

, a presentation from '' Destination Freedom'' {{DEFAULTSORT:Garrison, William Lloyd 1805 births 1879 deaths 19th-century American journalists 19th-century American male writers 19th-century American newspaper publishers (people) 19th century in Boston 19th-century Unitarians Abolitionists from Boston American libertarians American male journalists American newspaper editors American newspaper founders American people of Canadian descent American social reformers American tax resisters American Unitarians American women's rights activists Deaths from kidney disease People of Massachusetts in the American Civil War Writers from Newburyport, Massachusetts American printers American book publishers (people) American Anti-Slavery Society Underground Railroad in New York (state)

Against colonization

From the 18th century, there had been proposals to send freed slaves to Africa, considered as if it were a single country and ethnicity, where the slaves presumably "wanted to go back to". The U. S. Congress appropriated money, and a variety of churches and philanthropic organizations contributed to the endeavor. Slaves set free in the District of Columbia in 1862 were offered $100 if they would emigrate to Haiti or Liberia. The American Colonization Society eventually succeeded in creating the "colony", then country, ofLiberia

Liberia (), officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to its northwest, Guinea to its north, Ivory Coast to its east, and the Atlantic Ocean to its south and southwest. It ...

. The legal status of Liberia before its independence was never clarified; it was not a colony in the sense that Rhode Island or Pennsylvania had been colonies. When Liberia declared its independence in 1847, no country recognized it at first. Recognition by the United States was impeded by the Southerners who controlled Congress. When they departed ''en masse'' for the Confederacy

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between ...

, recognition quickly followed (1862), just as Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to ...

was admitted as a free state and slavery was prohibited in the District of Columbia at almost the same timeboth measures, the latter discussed for decades, that the Southern Slave Power contingent had blocked.

''The Liberator''

In 1831, Garrison, fully aware of the press as a means to bring about political change, returned to New England, where he co-founded a weekly anti-slavery newspaper, ''The Liberator

Liberator or The Liberators or ''variation'', may refer to:

Literature

* ''Liberators'' (novel), a 2009 novel by James Wesley Rawles

* ''The Liberators'' (Suvorov book), a 1981 book by Victor Suvorov

* ''The Liberators'' (comic book), a Britis ...

'', with his friend Isaac Knapp. In the first issue, Garrison stated:

Paid subscriptions to ''The Liberator'' were always fewer than its circulation. In 1834 it had two thousand subscribers, three-fourths of whom were black people. Benefactors paid to have the newspaper distributed free of charge to state legislators, governor's mansions, Congress, and the White House. Although Garrison rejected violence as a means for ending slavery, his critics saw him as a dangerous fanatic because he demanded immediate and total emancipation, without compensation to the slave owners. Nat Turner's slave rebellion in Virginia just seven months after ''The Liberator'' started publication fueled the outcry against Garrison in the South. A North Carolina grand jury indicted him for distributing incendiary material, and the Georgia Legislature offered a $5,000 reward () for his capture and conveyance to the state for trial.

Knapp parted from ''The Liberator'' in 1840. Later in 1845, when Garrison published a eulogy for his former partner and friend, he revealed that Knapp "was led by adversity and business mismanagement, to put the cup of intoxication to his lips," forcing the co-authors to part.

Among the anti-slavery essays and poems which Garrison published in ''The Liberator'' was an article in 1856 by a 14-year-old Anna Elizabeth Dickinson. ''The Liberator'' gradually gained a large following in the Northern states. It printed or reprinted many reports, letters, and news stories, serving as a type of community bulletin board for the abolition movement. By 1861 it had subscribers across the North, as well as in England, Scotland, and Canada. After the end of the Civil War and the abolition of slavery by the Thirteenth Amendment, Garrison published the last issue (number 1,820) on December 29, 1865, writing a "Valedictory" column. After reviewing his long career in journalism and the cause of abolitionism, he wrote:

Garrison and Knapp, printers and publishers

SeeList of publications of William Garrison and Isaac Knapp

In the 1830s, in addition to the newspaper ''The Liberator'', the Boston-based abolitionists William Garrison and Isaac Knapp printed and/or publish

Publishing is the activity of making information, literature, music, software and other con ...

.

Organization and reaction

In addition to publishing ''The Liberator'', Garrison spearheaded the organization of a new movement to demand the total abolition of slavery in the United States. By January 1832, he had attracted enough followers to organize theNew-England Anti-Slavery Society

The Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, headquartered in Boston, was organized as an auxiliary of the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1835. Its roots were in the New England Anti-Slavery Society, organized by William Lloyd Garrison, editor of ' ...

which, by the following summer, had dozens of affiliates and several thousand members. In December 1833, abolitionists from ten states founded the American Anti-Slavery Society (AAS). Although the New England society reorganized in 1835 as the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, enabling state societies to form in the other New England states, it remained the hub of anti-slavery agitation throughout the antebellum period. Many affiliates were organized by women who responded to Garrison's appeals for women to take an active part in the abolition movement. The largest of these was the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, which raised funds to support ''The Liberator'', publish anti-slavery pamphlets, and conduct anti-slavery petition drives.

The purpose of the American Anti-Slavery Society was the conversion of all Americans to the philosophy that "Slaveholding is a heinous crime in the sight of God" and that "duty, safety, and best interests of all concerned, require its ''immediate abandonment'' without expatriation."

Meanwhile, on September 4, 1834, Garrison married Helen Eliza Benson (1811–1876), the daughter of a retired abolitionist merchant. The couple had five sons and two daughters, of whom a son and a daughter died as children.

tar and feathers

Tarring and feathering is a form of public torture and punishment used to enforce unofficial justice or revenge. It was used in feudal Europe and its colonies in the early modern period, as well as the early American frontier, mostly as a ty ...

. The mayor intervened and Garrison was taken to the Leverett Street Jail for protection.

Gallows were erected in front of his house, and he was burned in effigy

An effigy is an often life-size sculptural representation of a specific person, or a prototypical figure. The term is mostly used for the makeshift dummies used for symbolic punishment in political protests and for the figures burned in certai ...

.

The woman question and division

Garrison's appeal for women's mass petitioning against slavery sparked controversy over women's right to a political voice. In 1837, women abolitionists from seven states convened in New York to expand their petitioning efforts and repudiate the social mores that proscribed their participation in public affairs. That summer, sisters Angelina Grimké and Sarah Grimké responded to the controversy aroused by their public speaking with treatises on woman's rightsAngelina's "Letters to Catherine E. Beecher" and Sarah's "Letters on the Equality of the Sexes and Condition of Woman"and Garrison published them first in ''The Liberator'' and then in book form. Instead of surrendering to appeals for him to retreat on the "woman question," Garrison announced in December 1837 that ''The Liberator'' would support "the rights of woman to their utmost extent." The Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society appointed women to leadership positions and hired Abby Kelley as the first of several female field agents.

In 1840, Garrison's promotion of woman's rights within the anti-slavery movement was one of the issues that caused some abolitionists, including New York brothers Arthur Tappan and Lewis Tappan, to leave the AAS and form the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, which did not admit women. In June of that same year, when the World Anti-Slavery Convention meeting in London refused to seat America's women delegates, Garrison, Charles Lenox Remond,

Garrison's appeal for women's mass petitioning against slavery sparked controversy over women's right to a political voice. In 1837, women abolitionists from seven states convened in New York to expand their petitioning efforts and repudiate the social mores that proscribed their participation in public affairs. That summer, sisters Angelina Grimké and Sarah Grimké responded to the controversy aroused by their public speaking with treatises on woman's rightsAngelina's "Letters to Catherine E. Beecher" and Sarah's "Letters on the Equality of the Sexes and Condition of Woman"and Garrison published them first in ''The Liberator'' and then in book form. Instead of surrendering to appeals for him to retreat on the "woman question," Garrison announced in December 1837 that ''The Liberator'' would support "the rights of woman to their utmost extent." The Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society appointed women to leadership positions and hired Abby Kelley as the first of several female field agents.

In 1840, Garrison's promotion of woman's rights within the anti-slavery movement was one of the issues that caused some abolitionists, including New York brothers Arthur Tappan and Lewis Tappan, to leave the AAS and form the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, which did not admit women. In June of that same year, when the World Anti-Slavery Convention meeting in London refused to seat America's women delegates, Garrison, Charles Lenox Remond, Nathaniel P. Rogers

Nathaniel Peabody Rogers (June 3, 1794 – October 16, 1846) was an American attorney turned abolitionist writer, who served, from June 1838 until June 1846, as editor of the New England anti-slavery newspaper '' Herald of Freedom''. He was als ...

, and William Adams refused to take their seat as delegates as well and joined the women in the spectator's gallery. The controversy introduced the woman's rights question not only to England but also to future woman's rights leader Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who attended the convention as a spectator, accompanying her delegate-husband, Henry B. Stanton.

Although Henry Stanton had cooperated in the Tappans' failed attempt to wrest leadership of the AAS from Garrison, he was part of another group of abolitionists unhappy with Garrison's influencethose who disagreed with Garrison's insistence that because the U.S. Constitution was a pro-slavery document, abolitionists should not participate in politics and government. A growing number of abolitionists, including Stanton, Gerrit Smith, Charles Turner Torrey, and Amos A. Phelps, wanted to form an anti-slavery political party and seek a political solution to slavery. They withdrew from the AAS in 1840, formed the Liberty Party, and nominated

Although Henry Stanton had cooperated in the Tappans' failed attempt to wrest leadership of the AAS from Garrison, he was part of another group of abolitionists unhappy with Garrison's influencethose who disagreed with Garrison's insistence that because the U.S. Constitution was a pro-slavery document, abolitionists should not participate in politics and government. A growing number of abolitionists, including Stanton, Gerrit Smith, Charles Turner Torrey, and Amos A. Phelps, wanted to form an anti-slavery political party and seek a political solution to slavery. They withdrew from the AAS in 1840, formed the Liberty Party, and nominated James G. Birney

James Gillespie Birney (February 4, 1792November 18, 1857) was an American abolitionist, politician, and attorney born in Danville, Kentucky. He changed from being a planter and slave owner to abolitionism, publishing the abolitionist weekly '' ...

for president. By the end of 1840, Garrison announced the formation of a third new organization, the Friends of Universal Reform

''Friends'' is an American television sitcom created by David Crane and Marta Kauffman, which aired on NBC from September 22, 1994, to May 6, 2004, lasting ten seasons. With an ensemble cast starring Jennifer Aniston, Courteney Cox, Lisa ...

, with sponsors and founding members including prominent reformers Maria Chapman

Maria Weston Chapman (July 25, 1806 – July 12, 1885) was an American abolitionist. She was elected to the executive committee of the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1839 and from 1839 until 1842, she served as editor of the anti-slavery jour ...

, Abby Kelley Foster, Oliver Johnson, and Amos Bronson Alcott (father of Louisa May Alcott).

Although some members of the Liberty Party supported woman's rights, including women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the women's rights, right of women to Suffrage, vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to gran ...

, Garrison's ''Liberator'' continued to be the leading advocate of woman's rights throughout the 1840s, publishing editorials, speeches, legislative reports, and other developments concerning the subject. In February 1849, Garrison's name headed the women's suffrage petition sent to the Massachusetts legislature, the first such petition sent to any American legislature, and he supported the subsequent annual suffrage petition campaigns organized by Lucy Stone and Wendell Phillips. Garrison took a leading role in the May 30, 1850, meeting that called the first National Woman's Rights Convention, saying in his address to that meeting that the new movement should make securing the ballot to women its primary goal. At the national convention held in Worcester the following October, Garrison was appointed to the National Woman's Rights Central Committee, which served as the movement's executive committee, charged with carrying out programs adopted by the conventions, raising funds, printing proceedings and tracts, and organizing annual conventions.

Controversy

In 1849, Garrison became involved in one of Boston's most notable trials of the time.Washington Goode

Washington Goode (1820 – May 25, 1849) was an African-American sailor who was hanged for murder in Boston in May 1849. His case was the subject of considerable attention by those opposed to the death penalty, resulting in over 24,000 signatures ...

, a black seaman, had been sentenced to death for the murder of a fellow black mariner, Thomas Harding. In ''The Liberator'' Garrison argued that the verdict relied on "circumstantial evidence of the most flimsy character ..." and feared that the determination of the government to uphold its decision to execute Goode was based on race. As all other death sentences since 1836 in Boston had been commuted, Garrison concluded that Goode would be the last person executed in Boston for a capital offense writing, "Let it not be said that the last man Massachusetts bore to hang was a colored man!" Despite the efforts of Garrison and many other prominent figures of the time, Goode was hanged on May 25, 1849.

Garrison became famous as one of the most articulate, as well as most radical, opponents of slavery. His approach to emancipation stressed "moral suasion," non-violence, and passive resistance. While some other abolitionists of the time favored gradual emancipation, Garrison argued for the "immediate and complete emancipation of all slaves." On July 4, 1854, he publicly burned a copy of the Constitution, condemning it as "a Covenant with Death, an Agreement with Hell," referring to the compromise that had written slavery into the Constitution.

In 1855, his eight-year alliance with Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he becam ...

disintegrated when Douglass converted to classical liberal legal theorist and abolitionist Lysander Spooner's view (dominant among political abolitionists) that the Constitution could be interpreted as being anti-slavery.

The events in John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, followed by Brown's trial and execution, were closely followed in ''The Liberator''. Garrison had Brown's last speech, in court, printed as a broadside, available in the ''Liberator'' office.

The events in John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, followed by Brown's trial and execution, were closely followed in ''The Liberator''. Garrison had Brown's last speech, in court, printed as a broadside, available in the ''Liberator'' office.

Garrison's outspoken anti-slavery views repeatedly put him in danger. Besides his imprisonment in Baltimore and the price placed on his head by the state of

Garrison's outspoken anti-slavery views repeatedly put him in danger. Besides his imprisonment in Baltimore and the price placed on his head by the state of Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to t ...

, he was the object of vituperation and frequent death threats. On the eve of the Civil War, a sermon preached in a Universalist chapel in Brooklyn, New York

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, behi ...

, denounced "the bloodthirsty sentiments of Garrison and his school; and did not wonder that the feeling of the South was exasperated, taking as they did, the insane and bloody ravings of the Garrisonian traitors for the fairly expressed opinions of the North."

After abolition

After the United States abolished slavery, Garrison announced in May 1865 that he would resign the presidency of the American Anti-Slavery Society and offered a resolution declaring victory in the struggle against slavery and dissolving the society. The resolution prompted a sharp debate, however, led by his long-time friend Wendell Phillips, who argued that the mission of the AAS was not fully completed until black Southerners gained full political and civil equality. Garrison maintained that while complete civil equality was vitally important, the special task of the AAS was at an end, and that the new task would best be handled by new organizations and new leadership. With his long-time allies deeply divided, however, he was unable to muster the support he needed to carry the resolution, and it was defeated 118–48. Declaring that his "vocation as an Abolitionist, thank God, has ended," Garrison resigned the presidency and declined an appeal to continue. Returning home toBoston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the capital city, state capital and List of municipalities in Massachusetts, most populous city of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financ ...

, he withdrew completely from the AAS and ended publication of ''The Liberator'' at the end of 1865. With Wendell Phillips at its head, the AAS continued to operate for five more years, until the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution granted voting rights to black men. (According to Henry Mayer, Garrison was hurt by the rejection, and remained peeved for years; "as the cycle came around, always managed to tell someone that he was ''not'' going to the next set of ASmeetings" 94)

After his withdrawal from AAS and ending ''The Liberator'', Garrison continued to participate in public reform movements. He supported the causes of civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life ...

for blacks and woman's rights, particularly the campaign for suffrage. He contributed columns on Reconstruction and civil rights for ''The Independent'' and '' The Boston Journal''.

In 1870, he became an associate editor of the women's suffrage newspaper, the ''Woman's Journal'', along with Mary Livermore, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Lucy Stone, and Henry B. Blackwell

Henry Browne Blackwell (May 4, 1825 – September 7, 1909), was an American advocate for social and economic reform. He was one of the founders of the Republican Party and the American Woman Suffrage Association. He published ''Woman's Journa ...

. He served as president of both the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) and the Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association. He was a major figure in New England's woman suffrage campaigns during the 1870s.

In 1873, he healed his long estrangements from Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he becam ...

and Wendell Phillips, affectionately reuniting with them on the platform at an AWSA rally organized by Abby Kelly Foster and Lucy Stone on the one-hundredth anniversary of the Boston Tea Party. When Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner (January 6, 1811March 11, 1874) was an American statesman and United States Senator from Massachusetts. As an academic lawyer and a powerful orator, Sumner was the leader of the anti-slavery forces in the state and a leader of th ...

died in 1874, some Republicans suggested Garrison as a possible successor to his Senate seat; Garrison declined on grounds of his moral opposition to taking office.

Antisemitism

Garrison was known to regularly traffic in Christian antisemitism. Garrison denounced the ancient Jews as an exclusivist people "whose feet ran to evil" and believed that theJewish diaspora

The Jewish diaspora ( he, תְּפוּצָה, təfūṣā) or exile (Hebrew: ; Yiddish: ) is the dispersion of Israelites or Jews out of their ancient ancestral homeland (the Land of Israel) and their subsequent settlement in other parts of ...

was a deserved punishment, writing that Jewish people deserved their "miserable dispersion in various parts of the earth, which continues to this day." When the Jewish-American sheriff and writer Mordecai Manuel Noah defended slavery, Garrison attacked Noah as "the miscreant Jew" and "the enemy of Christ and liberty." On other occasions, Garrison described Noah as a "Shylock" and as "the lineal descendant of the monsters who nailed Jesus to the cross."

Later life and death

Garrison spent more time at home with his family. He wrote weekly letters to his children and cared for his increasingly ill wife, Helen. She had suffered a small stroke on December 30, 1863, and was increasingly confined to the house. Helen died on January 25, 1876, after a severe cold worsened into

Garrison spent more time at home with his family. He wrote weekly letters to his children and cared for his increasingly ill wife, Helen. She had suffered a small stroke on December 30, 1863, and was increasingly confined to the house. Helen died on January 25, 1876, after a severe cold worsened into pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severi ...

. A quiet funeral was held in the Garrison home. Garrison, overcome with grief and confined to his bedroom with a fever and severe bronchitis, was unable to join the service. Wendell Phillips gave a eulogy and many of Garrison's old abolitionist friends joined him upstairs to offer their private condolences.

Garrison recovered slowly from the loss of his wife and began to attend Spiritualist circles in the hope of communicating with Helen. Garrison last visited England in 1877, where he met with George Thompson and other longtime friends from the British abolitionist movement.

Suffering from kidney disease, Garrison continued to weaken during April 1879. He moved to New York to live with his daughter Fanny's family. In late May, his condition worsened, and his five surviving children rushed to join him. Fanny asked if he would enjoy singing some hymns. Although he was unable to sing, his children sang favorite hymns while he beat time with his hands and feet. On May 24, 1879, Garrison lost consciousness and died just before midnight.

Garrison was buried in the Forest Hills Cemetery in Boston's Jamaica Plain neighborhood on May 28, 1879. At the public memorial service, eulogies were given by Theodore Dwight Weld and Wendell Phillips. Eight abolitionist friends, both white and black, served as his pallbearers. Flags were flown at half-staff all across

Suffering from kidney disease, Garrison continued to weaken during April 1879. He moved to New York to live with his daughter Fanny's family. In late May, his condition worsened, and his five surviving children rushed to join him. Fanny asked if he would enjoy singing some hymns. Although he was unable to sing, his children sang favorite hymns while he beat time with his hands and feet. On May 24, 1879, Garrison lost consciousness and died just before midnight.

Garrison was buried in the Forest Hills Cemetery in Boston's Jamaica Plain neighborhood on May 28, 1879. At the public memorial service, eulogies were given by Theodore Dwight Weld and Wendell Phillips. Eight abolitionist friends, both white and black, served as his pallbearers. Flags were flown at half-staff all across Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the capital city, state capital and List of municipalities in Massachusetts, most populous city of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financ ...

. Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he becam ...

, then employed as a United States Marshal

The United States Marshals Service (USMS) is a Federal law enforcement in the United States, federal law enforcement agency in the United States. The USMS is a Government agency, bureau within the United States Department of Justice, U.S. Depa ...

, spoke in memory of Garrison at a memorial service in a church in Washington, D.C., saying, "It was the glory of this man that he could stand alone with the truth, and calmly await the result."

Garrison's namesake son, William Lloyd Garrison, Jr. (1838–1909), was a prominent advocate of the single tax, free trade, women's suffrage, and of the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act

The Chinese Exclusion Act was a United States federal law signed by President Chester A. Arthur on May 6, 1882, prohibiting all immigration of Chinese laborers for 10 years. The law excluded merchants, teachers, students, travelers, and diplo ...

. His third son, Wendell Phillips Garrison (1840–1907), was literary editor of '' The Nation'' from 1865 to 1906. Two other sons (George Thompson Garrison and Francis Jackson Garrison, his biographer and named after abolitionist Francis Jackson) and a daughter, Helen Frances Garrison (who married Henry Villard), survived him. Fanny's son Oswald Garrison Villard became a prominent journalist, a founding member of the NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E.&nb ...

, and wrote an important biography of the abolitionist John Brown.

Legacy

Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich TolstoyTolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; russian: link=no, Лев Николаевич Толстой,In Tolstoy's day, his name was written as in pre-refor ...

was greatly influenced by the works of Garrison and his contemporary Adin Ballou

Adin Ballou (1803–1890) was an American proponent of Christian nonresistance, Christian anarchism and socialism, abolitionism and the founder of the Hopedale Community. Through his long career as a Universalist and Unitarian minister, he tir ...

, as their writings on Christian anarchism aligned with Tolstoy's burgeoning theo-political ideology. Along with Tolstoy publishing a short biography of Garrison in 1904, he frequently cited Garrison and his works in his non-fiction texts like '' The Kingdom of God Is Within You''. In a 2018 publication, American philosopher and anarchist Crispin Sartwell wrote that the works by Garrison and his other Christian anarchist contemporaries like Ballou directly influenced Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, Anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure ...

and Martin Luther King Jr., as well.

Memorials

* Boston installed a memorial to Garrison on the mall of Commonwealth Avenue. * In December 2005, to honor Garrison's 200th birthday, his descendants gathered in Boston for the first family reunion in about a century. They discussed the legacy and influence of their most notable family member. * A shared-use path along the John Greenleaf Whittier Bridge and Interstate 95 between Newburyport andAmesbury

Amesbury () is a town and civil parish in Wiltshire, England. It is known for the prehistoric monument of Stonehenge which is within the parish. The town is claimed to be the oldest occupied settlement in Great Britain, having been first sett ...

, Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

, was named in honor of Garrison. The 2-mile trail opened in 2018 after the new bridge was completed.

Works

Books

* * *Pamphlets

* * * * * *Broadside

* *Newspapers

Address at Park Street Church, Boston, July 4, 1829

(Garrison's first major public statement; an extensive statement of egalitarian principle). *

"Address to the Colonization Society"

(a slightly abridged version of the address July 4, 1829).

The Liberator, January 1, 1831 – December 29, 1865

. *

(Garrison's introductory column for ''The Liberator'', – January 1, 1831). *

Truisms

(''The Liberator'', January 8, 1831). *

The Insurrection

(Garrison's reaction to news of Nat Turner's rebellion, – ''The Liberator'', September 3, 1831). *

On the Constitution and the Union

(''The Liberator'', December 29, 1832). *

Abolition at the Ballot Box

(''The Liberator'', June 28, 1839). *

The American Union

(''The Liberator'', January 10, 1845). ** (September 24, 1855). *

The Tragedy at Harper's Ferry

, (''The Liberator'', October 28, 1859). *

John Brown and the Principle of Nonresistance

(Speech in the Tremont Temple, Boston, December 2, 1859, – the day Brown was hanged – ''The Liberator'', December 16, 1859). *

The War – Its Cause and Cure

(''The Liberator'', May 3, 1861). *

Valedictory: The Final Number of ''The Liberator''

(''The Liberator'', December 29, 1865).

The Liberator Files

(Horace Seldon's summary of research of Garrison's ''The Liberator'')

Declaration of Sentiments of the Nationale Anti-Slavery Convention

(December 1833, Philadelphia)

Declaration of Sentiments of The New England Non-Resistance Society

(''The Liberator'', September 28, 1838).

William Lloyd Garrison works

(Cornell University Library Samuel J. May Anti-Slavery Collection)

William Lloyd Garrison works

(Cornell University Digital Library Collections).

William Lloyd Garrison on non-resistance : together with a personal sketch by his daughter Fanny Garrison Villard and a tribute by Leo Tolstoy

Reading Garrison's Letters

(Horace Seldon's insight into the thought, work and life of Garrison, – based on "Letters of William Lloyd Garrison", Belknap Press of Harvard University, W. M. Merrill and L. Ruchames Editors).

The Liberator: William Lloyd Garrison, A Biography

(Boston; Little, Brown, 1963).

See also

*Garrison Literary and Benevolent Association The Garrison Literary and Benevolent Association was a 19th-century association of young African-American males whose purpose was promoting the abolition of slavery and the reformation of society.

Origins

This all-male club began in New York City i ...

* List of civil rights leaders

* List of women's rights activists

* Boston Vigilance Committee

References

Bibliography

* Abzug, Robert H. ''Cosmos Crumbling: American Reform and the Religious Imagination''. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994. . * Dal Lago, Enrico. ''William Lloyd Garrison and Giuseppe Mazzini: Abolition, Democracy, and Radical Reform.'' Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press, 2013. * * Hagedorn, Ann. ''Beyond The River: The Untold Story of the Heroes of the Underground Railroad''. Simon & Schuster, 2002. . * * Mayer, Henry. ''All on Fire: William Lloyd Garrison and the Abolition of Slavery.'' New York: St. Martin's Press, 1998. * McDaniel, W. Caleb. ''The Problem of Democracy in the Age of Slavery: Garrisonian Abolitionists and Transatlantic Reform.'' Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press, 2013. * Laurie, Bruce ''Beyond Garrison''. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005. . * Rodriguez, Junius P., ed. ''Encyclopedia of Emancipation and Abolition in the Transatlantic World''. (Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe, 2007) * * Thomas, John L. ''The Liberator: William Lloyd Garrison, A Biography.'' Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1963. .External links

* * *William Lloyd Garrison profile

on Spartacus Educational

''The Liberator Files'' online

Report of the Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice

*

William Lloyd Garrison

and

Who is William Lloyd Garrison?

– American Experience, PBS *

William Lloyd Garrison: Words of Thunder

" WGBH Forum

PBS Teachers Resources: William Lloyd Garrison 1805–1879

* The story of his life is retold in the radio drama

The Liberators (Part I)

, a presentation from '' Destination Freedom'' {{DEFAULTSORT:Garrison, William Lloyd 1805 births 1879 deaths 19th-century American journalists 19th-century American male writers 19th-century American newspaper publishers (people) 19th century in Boston 19th-century Unitarians Abolitionists from Boston American libertarians American male journalists American newspaper editors American newspaper founders American people of Canadian descent American social reformers American tax resisters American Unitarians American women's rights activists Deaths from kidney disease People of Massachusetts in the American Civil War Writers from Newburyport, Massachusetts American printers American book publishers (people) American Anti-Slavery Society Underground Railroad in New York (state)