William Kidd (merchant) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

William Kidd ( – 23 May 1701) also known as Captain William Kidd or simply Captain Kidd, was a Scottish

On 11 December 1695,

On 11 December 1695,

Kidd killed one of his own crewmen on 30 October 1697. Kidd's gunner William Moore was on deck sharpening a

Kidd killed one of his own crewmen on 30 October 1697. Kidd's gunner William Moore was on deck sharpening a

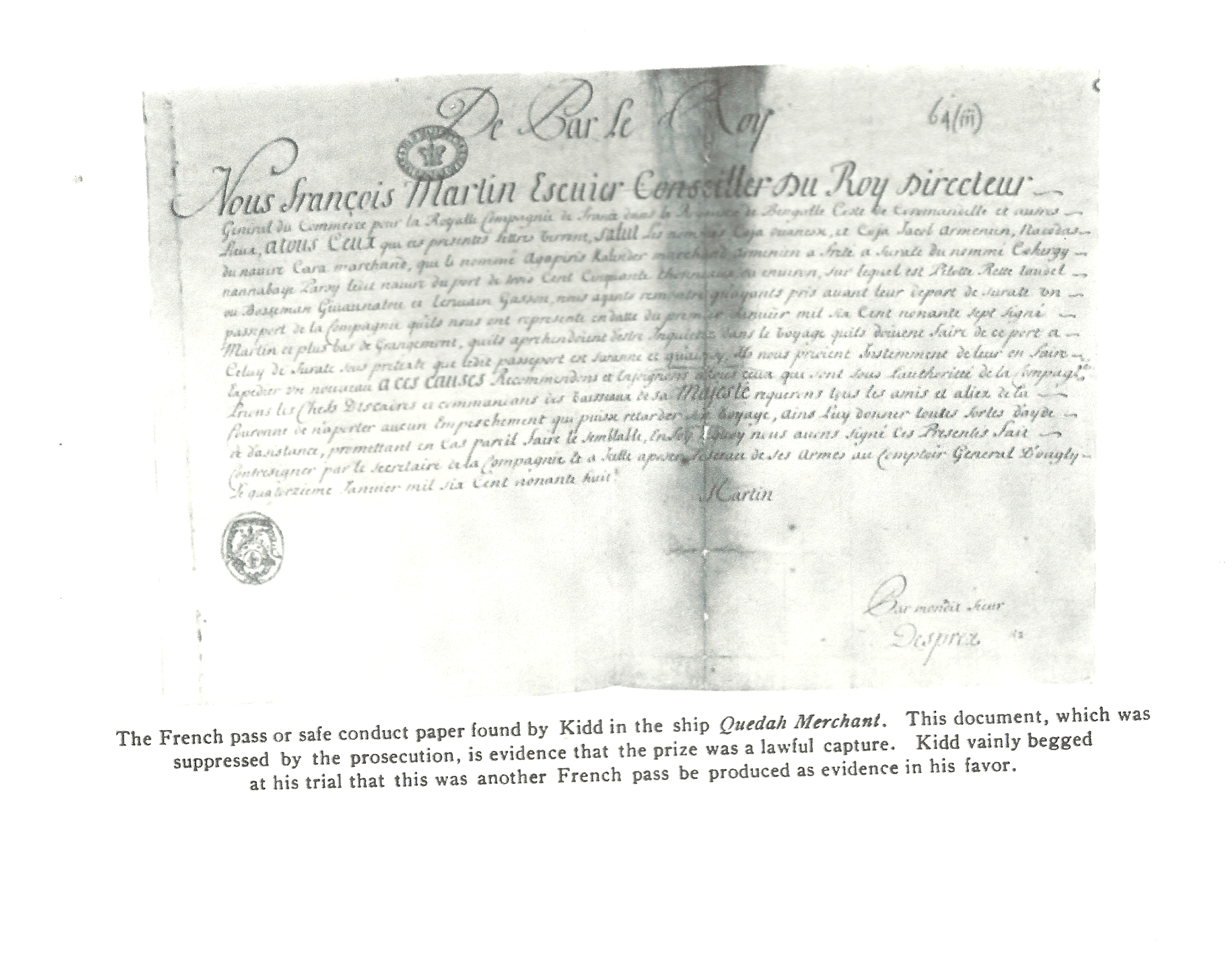

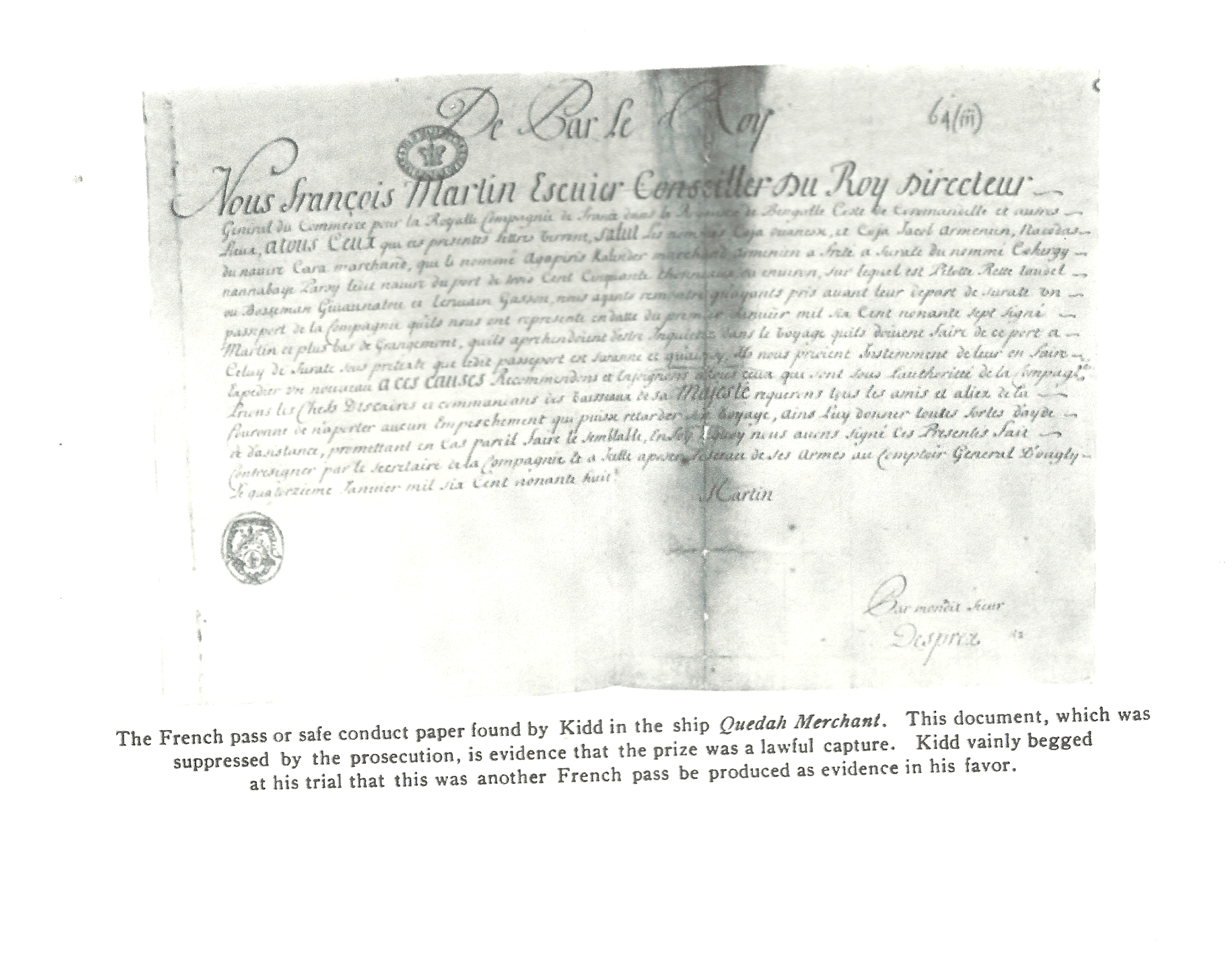

sea passes

of the ''Quedagh Merchant'', as well as the vessel itself. British admiralty and vice-admiralty courts (especially in North America) previously had often winked at privateers' excesses amounting to piracy. Kidd might have hoped that the passes would provide the legal fig leaf that would allow him to keep ''Quedagh Merchant'' and her cargo. Renaming the seized merchantman as ''Adventure Prize'', he set sail for

Kidd had two lawyers to assist in his defense. However, the money that the Admiralty had set aside for his defense was misplaced until right before the trials start, and he had no legal counsel until the morning that the trial started and had time for just one brief consultation with them before it began. He was shocked to learn at his trial that he was charged with murder. He was found guilty on all charges (murder and five counts of piracy) and sentenced to death. He was hanged in a public execution on 23 May 1701, at

Kidd had two lawyers to assist in his defense. However, the money that the Admiralty had set aside for his defense was misplaced until right before the trials start, and he had no legal counsel until the morning that the trial started and had time for just one brief consultation with them before it began. He was shocked to learn at his trial that he was charged with murder. He was found guilty on all charges (murder and five counts of piracy) and sentenced to death. He was hanged in a public execution on 23 May 1701, at  Kidd's Whig backers were embarrassed by his trial. Far from rewarding his loyalty, they participated in the effort to convict him by depriving him of the money and information which might have provided him with some legal defence. In particular, the two sets of French passes he had kept were missing at his trial. These passes (and others dated 1700) resurfaced in the early 20th century, misfiled with other government papers in a London building. These passes confirm Kidd's version of events, and call the extent of his guilt as a pirate into question.

A

Kidd's Whig backers were embarrassed by his trial. Far from rewarding his loyalty, they participated in the effort to convict him by depriving him of the money and information which might have provided him with some legal defence. In particular, the two sets of French passes he had kept were missing at his trial. These passes (and others dated 1700) resurfaced in the early 20th century, misfiled with other government papers in a London building. These passes confirm Kidd's version of events, and call the extent of his guilt as a pirate into question.

A

Captain Kidd

Pirate's Treasure Buried in the Connecticut River

* ttp://www.piratesinfo.com/biography/biography.php?article_id=36 Biography at piratesinfo.com

Dave's Blog

Blog, observer with the Indiana University expedition to the Quedagh Merchant (ongoing)

National Archives – Article listing Records held concerning Captain Kidd

Arraignment, Tryal and Condemnation of Captain William Kidd

The court documents of the trial of William Kidd, in Early Modern English.

Captain Kidd pub

, What's in Wapping? Local community website {{DEFAULTSORT:Kidd, William 1645 births 1701 deaths 17th-century Scottish people 18th-century Scottish people 17th-century American people 17th-century American criminals 18th-century American people 17th-century pirates American folklore Scottish emigrants to the Thirteen Colonies Executed Scottish people People executed for murder People executed for piracy People executed by Stuart England People from Dundee Military personnel from New York City People from colonial New York People associated with Inverclyde British privateers Scottish people convicted of murder Scottish pirates History of New York City People executed by the Kingdom of England by hanging People from Grand Manan Maritime folklore Murder convictions without a body Mutineers British military personnel of the Nine Years' War Piracy in the Indian Ocean Piracy in the Atlantic Ocean

privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

. Conflicting accounts exist regarding his early life, but he was likely born in Dundee

Dundee (; sco, Dundee; gd, Dùn Dè or ) is Scotland's fourth-largest city and the 51st-most-populous built-up area in the United Kingdom. The mid-year population estimate for 2016 was , giving Dundee a population density of 2,478/km2 or ...

and later settled in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

. By 1690, Kidd had become a highly successful privateer, commissioned to protect English interests in North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

and the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

.

In 1695, Kidd received a royal commission from the Earl of Bellomont

Earl of Bellomont, in the Kingdom of Ireland, was a title that was created three times in the Peerage of Ireland. The first creation came on 9 December 1680 when Charles Kirkhoven, 1st Baron Wotton, was made Earl of Bellomont. He had already bee ...

, the governor of New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, Massachusetts Bay

Massachusetts Bay is a bay on the Gulf of Maine that forms part of the central coastline of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

Description

The bay extends from Cape Ann on the north to Plymouth Harbor on the south, a distance of about . Its ...

and New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

, to hunt down pirates and enemy French ships in the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by th ...

. He received a letter of marque and set sail on a new ship, ''Adventure Galley

''Adventure Galley'', also known as ''Adventure'', was an English merchant ship captained by Scottish sea captain William Kidd. She was a type of hybrid ship that combined square rigged sails with oars to give her manoeuvrability in both windy ...

'', the following year. On his voyage he failed to find many targets, lost much of his crew and faced threats of mutiny. In 1698, Kidd captured his greatest prize, the 400-ton ''Quedagh Merchant

''Quedagh Merchant'' (; hy, Քեդահյան վաճառական '' Qedahyan Waćařakan''), also known as the ''Cara Merchant'' and the ''Adventure Prize'',Zacks, p. 266 was an Indian merchant vessel famously captured by Scottish privateer Wil ...

'', a ship hired by Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ''Ox ...

n merchants and captained by an Englishman. The political climate in England had turned against him, however, and he was denounced as a pirate. Bellomont engineered Kidd's arrest upon his return to Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

and sent him to stand trial in London. He was found guilty and hanged in 1701.

Kidd was romanticized after his death and his exploits became a popular subject of pirate-themed works of fiction. The belief that he had left buried treasure

Buried treasure is a literary trope commonly associated with depictions of pirates, criminals, and Old West outlaws. According to popular conception, these people often buried their stolen fortunes in remote places, intending to return to them ...

contributed significantly to his legend, which inspired numerous treasure hunts in the following centuries.

Life and career

Early life and education

Kidd was born inDundee

Dundee (; sco, Dundee; gd, Dùn Dè or ) is Scotland's fourth-largest city and the 51st-most-populous built-up area in the United Kingdom. The mid-year population estimate for 2016 was , giving Dundee a population density of 2,478/km2 or ...

, Scotland prior to 15 October 1654. While claims have been made of alternate birthplaces, including Greenock

Greenock (; sco, Greenock; gd, Grianaig, ) is a town and administrative centre in the Inverclyde council areas of Scotland, council area in Scotland, United Kingdom and a former burgh of barony, burgh within the Counties of Scotland, historic ...

and even Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdo ...

, he said himself he came from Dundee in a testimony given by Kidd to the High Court of Admiralty in 1695. There have also been records of his baptism taking place in Dundee. A local society supported the family financially after the death of the father. The myth that his "father was thought to have been a Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Scottish Reformation, Reformation of 1560, when it split from t ...

minister" has been discounted, insofar as there is no mention of the name in comprehensive Church of Scotland records for the period. Others still hold the contrary view.

Early voyages

As a young man, Kidd settled inNew York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

, which the English had taken over from the Dutch. There he befriended many prominent colonial citizens, including three governors. Some accounts suggest that he served as a seaman's apprentice

Apprenticeship is a system for training a new generation of practitioners of a trade or profession with on-the-job training and often some accompanying study (classroom work and reading). Apprenticeships can also enable practitioners to gain a ...

on a pirate ship during this time, before beginning his more famous seagoing exploits as a privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

.

By 1689, Kidd was a member of a French–English pirate crew sailing the Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean Se ...

under Captain Jean Fantin

Jean Fantin (fl. 1681–1689) was a French pirate active in the Caribbean and off the coast of Africa. He is best known for having his ship stolen by William Kidd and Robert Culliford.

History

The ship ''Le Trompeuse'' (The Trickster) passed thro ...

. During one of their voyages, Kidd and other crew members mutinied, ousting the captain and sailing to the British colony of Nevis

Nevis is a small island in the Caribbean Sea that forms part of the inner arc of the Leeward Islands chain of the West Indies. Nevis and the neighbouring island of Saint Kitts constitute one country: the Federation of Saint Kitts and Ne ...

. There they renamed the ship ''Blessed William

William of Hirsau (or Wilhelm von Hirschau) ( 1030 – 5 July 1091) was a Benedictine abbot and monastic reformer. He was abbot of Hirsau Abbey, for whom he created the ''Constitutiones Hirsaugienses'', based on the uses of Cluny, and was the fath ...

'', and Kidd became captain either as a result of election by the ship's crew, or by appointment of Christopher Codrington

Christopher Codrington (1668 – 7 April 1710) was a Barbadian-born colonial administrator, planter, book collector and military officer. He is sometimes known as Christopher Codrington the Younger to distinguish him from his father.

Codrington ...

, governor of the island of Nevis.

Kidd was an experienced leader and sailor by that time, and the ''Blessed William'' became part of Codrington's small fleet assembled to defend Nevis from the French, with whom the English were at war. The governor did not pay the sailors for their defensive service, telling them instead to take their pay from the French. Kidd and his men attacked the French island of Marie-Galante

Marie-Galante ( gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Mawigalant) is one of the islands that form Guadeloupe, an overseas department of France. Marie-Galante has a land area of . It had 11,528 inhabitants at the start of 2013, but by the start of 2018 ...

, destroying its only town and looting the area, and gathering around 2,000 pounds sterling.

Later, during the War of the Grand Alliance

The Nine Years' War (1688–1697), often called the War of the Grand Alliance or the War of the League of Augsburg, was a conflict between France and a European coalition which mainly included the Holy Roman Empire (led by the Habsburg monarch ...

, on commissions from the provinces of New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

and Massachusetts Bay

Massachusetts Bay is a bay on the Gulf of Maine that forms part of the central coastline of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

Description

The bay extends from Cape Ann on the north to Plymouth Harbor on the south, a distance of about . Its ...

, Kidd captured an enemy privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

off the New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

coast. Shortly afterwards, he was awarded £150 for successful privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

ing in the Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean Se ...

. One year later, Captain Robert Culliford, a notorious pirate, stole Kidd's ship while he was ashore at Antigua

Antigua ( ), also known as Waladli or Wadadli by the native population, is an island in the Lesser Antilles. It is one of the Leeward Islands in the Caribbean region and the main island of the country of Antigua and Barbuda. Antigua and Bar ...

in the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

.

In New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

, Kidd was active in financially supporting the construction of Trinity Church, New York

Trinity Church is a historic parish church in the Episcopal Diocese of New York, at the intersection of Wall Street and Broadway in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan in New York City. Known for its history, location, architecture and e ...

.

On 16 May 1691, Kidd married Sarah Bradley Cox Oort, who was still in her early twenties. She had already been twice widowed and was one of the wealthiest women in New York, based on an inheritance from her first husband.

Preparing his expedition

On 11 December 1695,

On 11 December 1695, Richard Coote, 1st Earl of Bellomont

Richard Coote, 1st Earl of Bellomont (sometimes spelled Bellamont, 1636 – 5 March 1700/01In the Julian calendar, then in use in England, the year began on 25 March. To avoid confusion with dates in the Gregorian calendar, then in us ...

, who was governing New York, Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

, and New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

, asked the "trusty and well beloved Captain Kidd"Hamilton, (1961) p. ? to attack Thomas Tew

Thomas Tew (died September 1695), also known as the Rhode Island Pirate, was a 17th-century English privateer-turned-pirate. He embarked on two major pirate voyages and met a bloody death on the second, and he pioneered the route which became kn ...

, John Ireland

John Benjamin Ireland (January 30, 1914 – March 21, 1992) was a Canadian actor. He was nominated for an Academy Award for his performance in ''All the King's Men'' (1949), making him the first Vancouver-born actor to receive an Oscar nomina ...

, Thomas Wake, William Maze, and all others who associated themselves with pirates, along with any enemy French ships. His request had the weight of the Crown behind it, and Kidd would have been considered disloyal, carrying much social stigma, to refuse Bellomont. This request preceded the voyage that contributed to Kidd's reputation as a pirate and marked his image in history and folklore

Folklore is shared by a particular group of people; it encompasses the traditions common to that culture, subculture or group. This includes oral traditions such as tales, legends, proverbs and jokes. They include material culture, ranging ...

.

Four-fifths of the cost for the 1696 venture was paid by noble lords, who were among the most powerful men in England: the Earl of Orford

Earl of Orford is a title that has been created three times.

The first creation came in the Peerage of England in 1697 when the naval commander Admiral of the Fleet Edward Russell was made Earl of Orford, in the County of Suffolk. He was cr ...

, the Baron of Romney, the Duke of Shrewsbury

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are ranked ...

, and Sir John Somers

John Somers, 1st Baron Somers, (4 March 1651 – 26 April 1716) was an English Whig jurist and statesman. Somers first came to national attention in the trial of the Seven Bishops where he was on their defence counsel. He published tracts on ...

. Kidd was presented with a letter of marque, signed personally by King William III of England

William III (William Henry; ; 4 November 16508 March 1702), also widely known as William of Orange, was the sovereign Prince of Orange from birth, Stadtholder of County of Holland, Holland, County of Zeeland, Zeeland, Lordship of Utrecht, Utrec ...

, which authorized him as a privateer. This letter reserved 10% of the loot for the Crown, and Henry Gilbert's ''The Book of Pirates'' suggests that the King fronted some of the money for the voyage himself. Kidd and his acquaintance Colonel Robert Livingston orchestrated the whole plan; they sought additional funding from merchant Sir Richard Blackham. Kidd also had to sell his ship ''Antigua'' to raise funds.

The new ship, ''Adventure Galley

''Adventure Galley'', also known as ''Adventure'', was an English merchant ship captained by Scottish sea captain William Kidd. She was a type of hybrid ship that combined square rigged sails with oars to give her manoeuvrability in both windy ...

'', was well suited to the task of catching pirates, weighing over 284 tons burthen

Builder's Old Measurement (BOM, bm, OM, and o.m.) is the method used in England from approximately 1650 to 1849 for calculating the cargo capacity of a ship. It is a volumetric measurement of cubic capacity. It estimated the tonnage of a ship bas ...

and equipped with 34 cannon

A cannon is a large- caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder ...

, oars, and 150 men. The oars were a key advantage, as they enabled ''Adventure Galley'' to manoeuvre in a battle when the winds had calmed and other ships were dead in the water. Kidd took pride in personally selecting the crew, choosing only those whom he deemed to be the best and most loyal officers.

Because of Kidd's refusal to salute, the Navy vessel's captain retaliated by pressing much of Kidd's crew into naval service Naval Service may refer to either:

* His Majesty's Naval Service, Britain's Royal Navy plus additional services

* Naval Service (Ireland), a branch of the Irish Defence Forces

* United States Department of the Navy, United States military department ...

, despite the captain's strong protests and the general exclusion of privateer crew from such action. Short-handed, Kidd sailed for New York City, capturing a French vessel en route (which was legal under the terms of his commission). To make up for the lack of officers, Kidd picked up replacement crew in New York, the vast majority of whom were known and hardened criminals, some likely former pirates.

Among Kidd's officers was quartermaster Hendrick van der Heul. The quartermaster was considered "second in command" to the captain in pirate culture of this era. It is not clear, however, if Van der Heul exercised this degree of responsibility because Kidd was authorised as a privateer. Van der Heul is notable because he might have been African or of Dutch descent. A contemporary source describes him as a "small black Man". If Van der Heul was of African ancestry, he would be considered the highest-ranking black pirate or privateer so far identified. Van der Heul later became a master's mate

Master's mate is an obsolete rating which was used by the Royal Navy, United States Navy and merchant services in both countries for a senior petty officer who assisted the master. Master's mates evolved into the modern rank of Sub-Lieutenant in t ...

on a merchant vessel and was never convicted of piracy.

Hunting for pirates

In September 1696, Kiddweighed anchor

Weigh anchor is a nautical term indicating the final preparation of a sea vessel for getting underway.

''Weighing anchor'' literally means raising the anchor of the vessel from the sea floor and hoisting it up to be stowed on board the vessel. At ...

and set course for the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is t ...

in southern Africa. A third of his crew died on the Comoros

The Comoros,, ' officially the Union of the Comoros,; ar, الاتحاد القمري ' is an independent country made up of three islands in southeastern Africa, located at the northern end of the Mozambique Channel in the Indian Ocean. It ...

due to an outbreak of cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

, the brand-new ship developed many leaks, and he failed to find the pirates whom he expected to encounter off Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Africa ...

.

With his ambitious enterprise failing, Kidd became desperate to cover its costs. Yet he failed to attack several ships when given a chance, including a Dutchman and a New York privateer. Both were out of bounds of his commission. The latter would have been considered out of bounds because New York was part of the territories of the Crown, and Kidd was authorised in part by the New York governor. Some of the crew deserted Kidd the next time that ''Adventure Galley'' anchored offshore. Those who decided to stay on made constant open threats of mutiny

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military, of a crew or of a crew of pirates) to oppose, change, or overthrow an organization to which they were previously loyal. The term is commonly used for a rebellion among member ...

.

Kidd killed one of his own crewmen on 30 October 1697. Kidd's gunner William Moore was on deck sharpening a

Kidd killed one of his own crewmen on 30 October 1697. Kidd's gunner William Moore was on deck sharpening a chisel

A chisel is a tool with a characteristically shaped cutting edge (such that wood chisels have lent part of their name to a particular grind) of blade on its end, for carving or cutting a hard material such as wood, stone, or metal by hand, stru ...

when a Dutch ship appeared. Moore urged Kidd to attack the Dutchman, an act that would have been considered piratical, since the nation was not at war with England, but also certain to anger Dutch-born King William. Kidd refused, calling Moore a lousy dog. Moore retorted, "If I am a lousy dog, you have made me so; you have brought me to ruin and many more." Kidd reportedly dropped an ironbound bucket on Moore, fracturing his skull. Moore died the following day.

Seventeenth-century English admiralty law

Admiralty law or maritime law is a body of law that governs nautical issues and private maritime disputes. Admiralty law consists of both domestic law on maritime activities, and private international law governing the relationships between priva ...

allowed captains great leeway in using violence against their crew, but killing was not permitted. Kidd said to his ship's surgeon that he had "good friends in England, that will bring me off for that".

Accusations of piracy

Escaped prisoners told stories of being hoisted up by the arms and "drubbed" (thrashed) with a drawncutlass

A cutlass is a short, broad sabre or slashing sword, with a straight or slightly curved blade sharpened on the cutting edge, and a hilt often featuring a solid cupped or basket-shaped guard. It was a common naval weapon during the early Age of ...

by Kidd. On one occasion, crew members sacked the trading ship ''Mary'' and tortured several of its crew members while Kidd and the other captain, Thomas Parker, conversed privately in Kidd's cabin.

Kidd was declared a pirate very early in his voyage by a Royal Navy officer, to whom he had promised "thirty men or so". Kidd sailed away during the night to preserve his crew, rather than subject them to Royal Navy impressment

Impressment, colloquially "the press" or the "press gang", is the taking of men into a military or naval force by compulsion, with or without notice. European navies of several nations used forced recruitment by various means. The large size of ...

. The letter of marque was intended to protect a privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

's crew from such impressment.

On 30 January 1698, Kidd raised French colours and took his greatest prize, the 400-ton ''Quedagh Merchant

''Quedagh Merchant'' (; hy, Քեդահյան վաճառական '' Qedahyan Waćařakan''), also known as the ''Cara Merchant'' and the ''Adventure Prize'',Zacks, p. 266 was an Indian merchant vessel famously captured by Scottish privateer Wil ...

'', an Indian ship hired by Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ''Ox ...

n merchants. It was loaded with satin

A satin weave is a type of fabric weave that produces a characteristically glossy, smooth or lustrous material, typically with a glossy top surface and a dull back. It is one of three fundamental types of textile weaves alongside plain weave ...

s, muslin

Muslin () is a cotton fabric of plain weave. It is made in a wide range of weights from delicate sheers to coarse sheeting. It gets its name from the city of Mosul, Iraq, where it was first manufactured.

Muslin of uncommonly delicate handsp ...

s, gold, silver, and a variety of East India

East India is a region of India consisting of the Indian states of Bihar, Jharkhand, Odisha

and West Bengal and also the union territory of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. The region roughly corresponds to the historical region of Magadh ...

n merchandise

Merchandising is any practice which contributes to the sale of products to a retail consumer. At a retail in-store level, merchandising refers to displaying products that are for sale in a creative way that entices customers to purchase more i ...

, as well as extremely valuable silks. The captain of ''Quedagh Merchant'' was an Englishman named Wright, who had purchased passes from the French East India Company promising him the protection of the French Crown.Hamilton, (1961)

When news of his capture of this ship reached England, however, officials classified Kidd as a pirate. Various naval commanders were ordered to "pursue and seize the said Kidd and his accomplices" for the "notorious piracies" they had committed.

Kidd kept the Frencsea passes

of the ''Quedagh Merchant'', as well as the vessel itself. British admiralty and vice-admiralty courts (especially in North America) previously had often winked at privateers' excesses amounting to piracy. Kidd might have hoped that the passes would provide the legal fig leaf that would allow him to keep ''Quedagh Merchant'' and her cargo. Renaming the seized merchantman as ''Adventure Prize'', he set sail for

Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Africa ...

.

On 1 April 1698, Kidd reached Madagascar. After meeting privately with trader Tempest Rogers

Tempest Rogers (1672 or 1675–1704) was a pirate trader active in the Caribbean and off Madagascar. He is best known for his association with William Kidd.

History

Tempest Rogers was born in 1672 or 1675, and by 1693 had married Johanna Little ...

(who would later be accused of trading and selling Kidd's looted East India goods) he found the first pirate of his voyage, Robert Culliford

Robert Culliford (c. 1666 - ?, last name occasionally Collover) was a pirate from Cornwall who is best remembered for repeatedly ''checking the designs'' of Captain William Kidd.

Early career and capture

Culliford and Kidd first met as shipmates ...

(the same man who had stolen Kidd's ship at Antigua years before) and his crew aboard ''Mocha Frigate''.

Two contradictory accounts exist of how Kidd proceeded. According to ''A General History of the Pyrates

''A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the most notorious Pyrates'' is a 1724 book published in Britain containing biographies of contemporary pirates,

'', published more than 25 years after the event by an author whose identity is disputed by historians, Kidd made peaceful overtures to Culliford: he "drank their Captain's health", swearing that "he was in every respect their Brother", and gave Culliford "a Present of an Anchor and some Guns". This account appears to be based on the testimony of Kidd's crewmen Joseph Palmer and Robert Bradinham at his trial.

The other version was presented by Richard Zacks in his 2002 book ''The Pirate Hunter: The True Story of Captain Kidd''. According to Zacks, Kidd was unaware that Culliford had only about 20 crew with him, and felt ill-manned and ill-equipped to take ''Mocha Frigate'' until his two prize ships and crews arrived. He decided to leave Culliford alone until these reinforcements arrived. After ''Adventure Prize'' and ''Rouparelle'' reached port, Kidd ordered his crew to attack Culliford's ''Mocha Frigate''. However, his crew refused to attack Culliford and threatened instead to shoot Kidd. Zacks does not refer to any source for his version of events.

Both accounts agree that most of Kidd's men abandoned him for Culliford. Only 13 remained with ''Adventure Galley''. Deciding to return home, Kidd left the ''Adventure Galley

''Adventure Galley'', also known as ''Adventure'', was an English merchant ship captained by Scottish sea captain William Kidd. She was a type of hybrid ship that combined square rigged sails with oars to give her manoeuvrability in both windy ...

'' behind, ordering her to be burnt because she had become worm-eaten and leaky. Before burning the ship, he salvaged every last scrap of metal, such as hinges. With the loyal remnant of his crew, he returned to the Caribbean aboard the ''Adventure Prize'', stopping first at St. Augustine's Bay

The Bay of Saint-Augustin is located on the southwestern coast of Madagascar in the region of Atsimo-Andrefana at the Mozambique Channel. This bay is the mouth of the Onilahy River at a distance of 35 kilometres south of Toliara

Toliara (also kno ...

for repairs. Some of his crew later returned to North America on their own as passengers aboard Giles Shelley

Giles Shelley (born May 1645 (?), died 1710, last name occasionally Shelly) was a pirate trader active between New York and Madagascar.

History

Shelley commanded the 4-gun or 6-gun vessel ''Nassau'' on supply runs between New York and the pirate ...

's ship ''Nassau''.

The 1698 Act of Grace

Acts of grace, in the context of piracy, were state proclamations offering pardons (often royal pardons) for acts of piracy. General pardons for piracy were offered on numerous occasions and by multiple states, for instance by the Kingdom of Engl ...

, which offered a royal pardon

In the English and British tradition, the royal prerogative of mercy is one of the historic royal prerogatives of the British monarch, by which they can grant pardons (informally known as a royal pardon) to convicted persons. The royal preroga ...

to pirates in the Indian Ocean, specifically exempted Kidd (and Henry Every

Henry Every, also known as Henry Avery (20 August 1659after 1696), sometimes erroneously given as Jack Avery or John Avery, was an English pirate who operated in the Atlantic and Indian oceans in the mid-1690s. He probably used several aliases ...

) from receiving a pardon, in Kidd's case due to his association with prominent Whig statesmen. Kidd became aware both that he was wanted and that he could not make use of the Act of Grace upon his arrival in Anguilla

Anguilla ( ) is a British Overseas Territory in the Caribbean. It is one of the most northerly of the Leeward Islands in the Lesser Antilles, lying east of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands and directly north of Saint Martin. The territo ...

, his first port of call since St. Augustine's Bay.

Trial and execution

Prior to returning to New York City, Kidd knew that he was wanted as a pirate and that several Englishmen-of-war

The man-of-war (also man-o'-war, or simply man) was a Royal Navy expression for a powerful warship or frigate from the 16th to the 19th century. Although the term never acquired a specific meaning, it was usually reserved for a ship armed wi ...

were searching for him. Realizing that ''Adventure Prize'' was a marked vessel, he cached it in the Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea ( es, Mar Caribe; french: Mer des Caraïbes; ht, Lanmè Karayib; jam, Kiaribiyan Sii; nl, Caraïbische Zee; pap, Laman Karibe) is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean in the tropics of the Western Hemisphere. It is bounded by Mexico ...

, sold off his remaining plundered goods through pirate and fence William Burke, and continued towards New York aboard a sloop. He deposited some of his treasure on Gardiners Island

Gardiner's Island is a small island in the Town of East Hampton, New York, in Eastern Suffolk County. It is located in Gardiner's Bay between the two peninsulas at the east end of Long Island. It is long, wide and has of coastline.

The isl ...

, hoping to use his knowledge of its location as a bargaining tool. Kidd landed in Oyster Bay to avoid mutinous crew who had gathered in New York City. To avoid them, Kidd sailed around the eastern tip of Long Island, and doubled back along the Sound to Oyster Bay. He felt this was a safer passage than the highly trafficked Narrows

A narrows or narrow (used interchangeably but usually in the plural form), is a restricted land or water passage. Most commonly a narrows is a strait, though it can also be a water gap.

A narrows may form where a stream passes through a tilted ...

between Staten Island

Staten Island ( ) is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Richmond County, in the U.S. state of New York. Located in the city's southwest portion, the borough is separated from New Jersey by the Arthur Kill and the Kill Van Kull an ...

and Brooklyn

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

.

New York Governor Bellomont, also an investor, was away in Boston, Massachusetts. Aware of the accusations against Kidd, Bellomont was afraid of being implicated in piracy himself and believed that presenting Kidd to England in chains was his best chance to survive. He lured Kidd into Boston with false promises of clemency, and ordered him arrested on 6 July 1699. Kidd was placed in Stone Prison, spending most of the time in solitary confinement

Solitary confinement is a form of imprisonment in which the inmate lives in a single cell with little or no meaningful contact with other people. A prison may enforce stricter measures to control contraband on a solitary prisoner and use additi ...

. His wife, Sarah, was also arrested and imprisoned. They were separated and she never saw him again.

The conditions of Kidd's imprisonment were extremely harsh, and were said to have driven him at least temporarily insane. By then, Bellomont had turned against Kidd and other pirates, writing that the inhabitants of Long Island

Long Island is a densely populated island in the southeastern region of the U.S. state of New York (state), New York, part of the New York metropolitan area. With over 8 million people, Long Island is the most populous island in the United Sta ...

were "a lawless and unruly people" protecting pirates who had "settled among them".

The civil government had changed and the new Tory

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. Th ...

ministry hoped to use Kidd as a tool to discredit the Whigs who had backed him, but Kidd refused to name names, naively confident his patrons would reward his loyalty by interceding on his behalf. There is speculation that he could have been spared had he talked. Finding Kidd politically useless, the Tory leaders sent him to stand trial before the High Court of Admiralty

Admiralty courts, also known as maritime courts, are courts exercising jurisdiction over all maritime contracts, torts, injuries, and offences.

Admiralty courts in the United Kingdom England and Wales

Scotland

The Scottish court's earliest ...

in London, for the charges of piracy on high seas and the murder of William Moore. Whilst awaiting trial, Kidd was confined in the infamous Newgate Prison

Newgate Prison was a prison at the corner of Newgate Street and Old Bailey Street just inside the City of London, England, originally at the site of Newgate, a gate in the Roman London Wall. Built in the 12th century and demolished in 1904, t ...

, regarded even by the standards of the day as a disgusting hellhole, and was held there for almost 2 years before his trial even began.

Kidd had two lawyers to assist in his defense. However, the money that the Admiralty had set aside for his defense was misplaced until right before the trials start, and he had no legal counsel until the morning that the trial started and had time for just one brief consultation with them before it began. He was shocked to learn at his trial that he was charged with murder. He was found guilty on all charges (murder and five counts of piracy) and sentenced to death. He was hanged in a public execution on 23 May 1701, at

Kidd had two lawyers to assist in his defense. However, the money that the Admiralty had set aside for his defense was misplaced until right before the trials start, and he had no legal counsel until the morning that the trial started and had time for just one brief consultation with them before it began. He was shocked to learn at his trial that he was charged with murder. He was found guilty on all charges (murder and five counts of piracy) and sentenced to death. He was hanged in a public execution on 23 May 1701, at Execution Dock

Execution Dock was a place in the River Thames near the shoreline at Wapping, London, that was used for more than 400 years to execute pirates, smugglers and mutineers who had been sentenced to death by Admiralty courts. The "dock" consisted of ...

, Wapping

Wapping () is a district in East London in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. Wapping's position, on the north bank of the River Thames, has given it a strong maritime character, which it retains through its riverside public houses and steps, ...

, in London. He had to be hanged twice. On the first attempt, the hangman's rope broke and Kidd survived. Although some in the crowd called for Kidd's release, claiming the breaking of the rope was a sign from God, Kidd was hanged again minutes later, and died. His body was gibbet

A gibbet is any instrument of public execution (including guillotine, decapitation, executioner's block, Impalement, impalement stake, gallows, hanging gallows, or related Scaffold (execution site), scaffold). Gibbeting is the use of a gallows- ...

ed over the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, se ...

at Tilbury Point, as a warning to future would-be pirates, for three years.

Of Kidd's associates, Gabriel Loffe, Able Owens, and Hugh Parrot were also convicted of piracy. They were pardoned just prior to hanging at Execution Dock. Robert Lamley, William Jenkins and Richard Barleycorn were released.

Kidd's Whig backers were embarrassed by his trial. Far from rewarding his loyalty, they participated in the effort to convict him by depriving him of the money and information which might have provided him with some legal defence. In particular, the two sets of French passes he had kept were missing at his trial. These passes (and others dated 1700) resurfaced in the early 20th century, misfiled with other government papers in a London building. These passes confirm Kidd's version of events, and call the extent of his guilt as a pirate into question.

A

Kidd's Whig backers were embarrassed by his trial. Far from rewarding his loyalty, they participated in the effort to convict him by depriving him of the money and information which might have provided him with some legal defence. In particular, the two sets of French passes he had kept were missing at his trial. These passes (and others dated 1700) resurfaced in the early 20th century, misfiled with other government papers in a London building. These passes confirm Kidd's version of events, and call the extent of his guilt as a pirate into question.

A broadside

Broadside or broadsides may refer to:

Naval

* Broadside (naval), terminology for the side of a ship, the battery of cannon on one side of a warship, or their near simultaneous fire on naval warfare

Printing and literature

* Broadside (comic ...

song, "Captain Kidd's Farewell to the Seas, or, the Famous Pirate's Lament", was printed shortly after his execution. It popularised the common belief that Kidd had confessed to the charges.The complete words of the original broadside song "Captain Kid's Farewel to the Seas, or, the Famous Pirate's Lament, to the tune of Coming Down" are at ''davidkidd.net''.

Mythology and legend

The belief that Kidd had leftburied treasure

Buried treasure is a literary trope commonly associated with depictions of pirates, criminals, and Old West outlaws. According to popular conception, these people often buried their stolen fortunes in remote places, intending to return to them ...

contributed greatly to the growth of his legend. The 1701 broadside

Broadside or broadsides may refer to:

Naval

* Broadside (naval), terminology for the side of a ship, the battery of cannon on one side of a warship, or their near simultaneous fire on naval warfare

Printing and literature

* Broadside (comic ...

song "Captain Kid's Farewell to the Seas, or, the Famous Pirate's Lament" lists "Two hundred bars of gold, and rix dollars manifold, we seized uncontrolled".

It also inspired numerous treasure hunts conducted on Oak Island

Oak Island is a privately owned island in Lunenburg County on the south shore of Nova Scotia, Canada. The tree-covered island is one of several islands in Mahone Bay, and is connected to the mainland by a causeway. The nearest community is the ...

in Nova Scotia; in Suffolk County, Long Island

Long Island is a densely populated island in the southeastern region of the U.S. state of New York (state), New York, part of the New York metropolitan area. With over 8 million people, Long Island is the most populous island in the United Sta ...

in New York where Gardiner's Island

Gardiner's Island is a small island in the Town of East Hampton, New York, in Eastern Suffolk County. It is located in Gardiner's Bay between the two peninsulas at the east end of Long Island. It is long, wide and has of coastline.

The isl ...

is located; Charles Island

Charles Island is a 14-acre (57,000 m2) island located roughly 0.5 mile (1 km) off the coast of Milford, Connecticut, in Long Island Sound centered at .

Charles Island is accessible from shore via a tombolo (locally referred to as a san ...

in Milford, Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its cap ...

; the Thimble Islands

The Thimble Islands is an archipelago consisting of small islands in Long Island Sound, located in and around the harbor of Stony Creek in the southeast corner of Branford, Connecticut. The islands are under the jurisdiction of the United Sta ...

in Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its cap ...

and Cockenoe Island

Cockenoe (also known as Cockeno, Cockenow, Chachaneu, Cheekanoo, Cockenoe, Chickino, Chekkonnow, Cockoo) (born before 1630 and died after 1687) was an early Native American translator from Long Island in New York where he was a member of the Mon ...

in Westport, Connecticut

Westport is a town in Fairfield County, Connecticut, United States, along the Long Island Sound within Connecticut's Gold Coast. It is northeast of New York City. The town had a population of 27,141 according to the 2020 U.S. Census.

History

...

.

Kidd was also alleged to have buried treasure on the Rahway River

The Rahway River is a river in Essex, Middlesex, and Union Counties, New Jersey, United States, The Rahway, along with the Elizabeth River, Piles Creek, Passaic River, Morses Creek, the Fresh Kills River (in Staten Island), has its river m ...

in New Jersey across the Arthur Kill

The Arthur Kill (sometimes referred to as the Staten Island Sound) is a tidal strait between Staten Island (also known as Richmond County), New York and Union and Middlesex counties, New Jersey. It is a major navigational channel of the Port of ...

from Staten Island.

Captain Kidd did bury a small cache of treasure on Gardiners Island

Gardiner's Island is a small island in the Town of East Hampton, New York, in Eastern Suffolk County. It is located in Gardiner's Bay between the two peninsulas at the east end of Long Island. It is long, wide and has of coastline.

The isl ...

off the eastern coast of Long Island, New York, in a spot known as Cherry Tree Field. Governor Bellomont reportedly had it found and sent to England to be used as evidence against Kidd in his trial.

Some time in the 1690s, Kidd visited Block Island

Block Island is an island in the U.S. state of Rhode Island located in Block Island Sound approximately south of the mainland and east of Montauk Point, Long Island, New York, named after Dutch explorer Adriaen Block. It is part of Washingt ...

where he was supplied with provisions by Mrs. Mercy (Sands) Raymond, daughter of the mariner James Sands. It was said that before he departed, Kidd asked Mrs. Raymond to hold out her apron, which he then filled with gold and jewels as payment for her hospitality. After her husband Joshua Raymond died, Mercy moved with her family to northern New London, Connecticut

New London is a seaport city and a port of entry on the northeast coast of the United States, located at the mouth of the Thames River in New London County, Connecticut. It was one of the world's three busiest whaling ports for several decades ...

(later Montville) where she purchased much land. The Raymond family was said by family acquaintances to have been "enriched by the apron".

On Grand Manan

Grand Manan is a Canadian island in the Bay of Fundy. Grand Manan is also the name of an incorporated village, which includes the main island and all of its adjacent islands, except White Head Island. It is governed as a village and is part of t ...

in the Bay of Fundy

The Bay of Fundy (french: Baie de Fundy) is a bay between the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, with a small portion touching the U.S. state of Maine. It is an arm of the Gulf of Maine. Its extremely high tidal range is the hi ...

, as early as 1875, there were searches on the west side of the island for treasure allegedly buried by Kidd during his time as a privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

. For nearly 200 years, this remote area of the island has been called "Money Cove".

In 1983, Cork Graham

Frederick Graham (born November 29, 1964), who writes under the name Cork Graham, is an American author of adventure memoir and political thriller fiction novels. He is a former combat photographer, who was imprisoned in Vietnam for illegally e ...

and Richard Knight searched for Captain Kidd's buried treasure off the Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

ese island of Phú Quốc

Phú Quốc () is the largest island in Vietnam. Phú Quốc and nearby islands, along with the distant Thổ Chu Islands, are part of Kiên Giang Province as Phú Quốc City, the island has a total area of and a permanent population of appro ...

. Knight and Graham were caught, convicted of illegally landing on Vietnamese territory, and each assessed a $10,000 fine

Fine may refer to:

Characters

* Sylvia Fine (''The Nanny''), Fran's mother on ''The Nanny''

* Officer Fine, a character in ''Tales from the Crypt'', played by Vincent Spano

Legal terms

* Fine (penalty), money to be paid as punishment for an offe ...

. They were imprisoned for 11 months until they paid the fine.

''Quedagh Merchant'' found

For years, people and treasure hunters tried to locate the ''Quedagh Merchant

''Quedagh Merchant'' (; hy, Քեդահյան վաճառական '' Qedahyan Waćařakan''), also known as the ''Cara Merchant'' and the ''Adventure Prize'',Zacks, p. 266 was an Indian merchant vessel famously captured by Scottish privateer Wil ...

''. It was reported on 13 December 2007 that "wreckage of a pirate ship abandoned by Captain Kidd in the 17th century has been found by divers in shallow waters off the Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic ( ; es, República Dominicana, ) is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean region. It occupies the eastern five-eighths of the island, which it shares wit ...

". The waters in which the ship was found were less than ten feet deep and were only off Catalina Island, just to the south of La Romana on the Dominican coast. The ship is believed to be "the remains of the ''Quedagh Merchant''". Charles Beeker, the director of Academic Diving and Underwater Science Programs in Indiana University (Bloomington)

Indiana University Bloomington (IU Bloomington, Indiana University, IU, or simply Indiana) is a public research university in Bloomington, Indiana. It is the flagship campus of Indiana University and, with over 40,000 students, its largest campu ...

's School of Health, Physical Education, and Recreation, was one of the experts leading the Indiana University

Indiana University (IU) is a system of public universities in the U.S. state of Indiana.

Campuses

Indiana University has two core campuses, five regional campuses, and two regional centers under the administration of IUPUI.

*Indiana Universit ...

diving team. He said that it was "remarkable that the wreck has remained undiscovered all these years given its location", and that the ship had been the subject of so many prior failed searches. Captain Kidd's cannon, an artifact from the shipwreck, was added to a permanent exhibit at The Children's Museum of Indianapolis

The Children's Museum of Indianapolis is the world's largest children's museum. It is located at 3000 North Meridian Street, Indianapolis, Indiana in the United Northwest Area neighborhood of the city. The museum is accredited by the American Al ...

in 2011.

False find

In May 2015, a ingot expected to be silver was found in a wreck off the coast ofÎle Sainte-Marie

Nosy Boraha , previously known as Sainte-Marie, main town Ambodifotatra, is an island off the east coast of Madagascar. The island forms an administrative district within Analanjirofo Region, and covers an area of 222 km2.

It has a popula ...

in Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Africa ...

by a team led by marine archaeologist Barry Clifford

Barry Clifford (born May 30, 1945) is an American underwater archaeological explorer, best known for discovering the remains of Samuel Bellamy's wrecked pirate ship ''Whydah'' ronounced ''wih-duh'' the only fully verified and authenticated pirat ...

. It was believed to be part of Captain Kidd's treasure. Clifford gave the booty to Hery Rajaonarimampianina

Hery Martial Rajaonarimampianina Rakotoarimanana (; ; born 6 November 1958) is a Malagasy politician who was President of Madagascar from January 2014 to September 2018, resigning to run for re-election. Previously he served as Minister of Fina ...

, President of Madagascar. But, in July 2015, a UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

scientific and technical advisory body reported that testing showed the ingot consisted of 95% lead, and speculated that the wreck in question was a broken part of the Sainte-Marie port constructions.

Portrayals in popular culture

Literature

*Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe (; Edgar Poe; January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849) was an American writer, poet, editor, and literary critic. Poe is best known for his poetry and short stories, particularly his tales of mystery and the macabre. He is wide ...

uses the legend of Kidd's buried treasure in his story "The Gold Bug

"The Gold-Bug" is a short story by American writer Edgar Allan Poe published in 1843. The plot follows William Legrand, who was bitten by a gold-colored bug. His servant Jupiter fears that Legrand is going insane and goes to Legrand's friend, an ...

" (1843).

*The 1957 children's book ''Captain Kidd's Cat'' by Robert Lawson is a largely fictionalized account of Kidd's last voyage, trial and execution. It is told from the point of view of his loyal ship's cat. The book portrays Kidd as an innocent privateer who was framed by corrupt officials as a scapegoat for their own crimes.

*In the popular manga ''One Piece

''One Piece'' (stylized in all caps) is a Japanese manga series written and illustrated by Eiichiro Oda. It has been serialized in Shueisha's ''shōnen'' manga magazine ''Weekly Shōnen Jump'' since July 1997, with its individual chapte ...

'', "Captain" Eustass Kid is based on him.

*Bob Dylan used Captain Kidd in the lyrics to "Bob Dylan's 115th Dream".

Film and television

*Stanley Andrews

Stanley Andrews (born Stanley Martin Andrzejewski; August 28, 1891 – June 23, 1969) was an American actor perhaps best known as the voice of Daddy Warbucks on the radio program ''Little Orphan Annie'' and later as "The Old Ranger", the first ...

as Kidd. Captain Kidd's Treasure (Short 1938).

*Charles Laughton

Charles Laughton (1 July 1899 – 15 December 1962) was a British actor. He was trained in London at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art and first appeared professionally on the stage in 1926. In 1927, he was cast in a play with his future w ...

played Kidd twice on film: in ''Captain Kidd

William Kidd, also known as Captain William Kidd or simply Captain Kidd ( – 23 May 1701), was a Scottish sea captain who was commissioned as a privateer and had experience as a pirate. He was tried and executed in London in 1701 for murder a ...

'' (1945) and in ''Abbott and Costello Meet Captain Kidd

''Abbott and Costello Meet Captain Kidd'' is a 1952 comedy film directed by Charles Lamont and starring the comedy team of Abbott and Costello, along with Charles Laughton, who reprised his role as the infamous pirate from the 1945 film ''Captain ...

'' (1952).

* John Crawford played Kidd in the 1953 Columbia film serial ''The Great Adventures of Captain Kidd

''The Great Adventures of Captain Kidd'' (1953) was the 52nd serial released by Columbia Pictures. It is based in the historical figure of Captain William Kidd.

Plot

In 1697, agents Richard Dale and Alan Duncan are sent on an undercover missio ...

''.

*Love Nystrom portrayed Kidd in the 2006 mini-series ''Blackbeard

Edward Teach (alternatively spelled Edward Thatch, – 22 November 1718), better known as Blackbeard, was an English Piracy, pirate who operated around the West Indies and the eastern coast of Britain's Thirteen Colonies, North American colon ...

''.

*Noah Robbins

Noah Robbins is an American actor.

Background

Robbins is a native of Washington, D.C. and graduated from Georgetown Day School in 2009. Robbins made his Broadway debut in the 2009 production of ''Brighton Beach Memoirs

''Brighton Beach Mem ...

played William Benedict, a man who used the alias of Captain Kidd in the 11th episode of Season 8

A season is a division of the year based on changes in weather, ecology, and the number of daylight hours in a given region. On Earth, seasons are the result of the axial parallelism of Earth's axial tilt, tilted orbit around the Sun. In tempera ...

of the TV series ''The Blacklist

''The Blacklist'' is an American crime thriller television series that premiered on NBC on September 23, 2013. The show follows Raymond "Red" Reddington (James Spader), a former U.S. Navy officer turned high-profile criminal who voluntarily sur ...

''.

Music

* The traditional folk song " The Ballad of Captain Kidd" was popular from its publication at the time of Kidd's death, surviving in the oral tradition into the twentieth century and giving its melody to the hymn "What Wondrous Love Is This

"What Wondrous Love Is This" (often just referred to as "Wondrous Love") is a Christian folk hymn from the American South. Its text was first published in 1811, during the Second Great Awakening, and its melody derived from a popular English balla ...

".

* The song "Ballad of William Kidd" by the heavy metal band Running Wild is based on Kidd's life, particularly the events surrounding his trial and execution.

* Canadian band Great Big Sea

Great Big Sea was a Canadian folk rock band from Newfoundland and Labrador, best known for performing energetic rock interpretations of traditional Newfoundland folk songs including sea shanties, which draw from the island's 500-year Irish, Scot ...

wrote and recorded the ballad "Captain Kidd". It is a sea chanty with many historically accurate allusions to the life of William Kidd.

* He is mentioned in The Land of Make Believe by Bucks Fizz

Bucks Fizz were a British pop group that achieved success in the 1980s, most notably for winning the 1981 Eurovision Song Contest with the song "Making Your Mind Up". The group was formed in January 1981 specifically for the contest and comp ...

.

Video games

*In ''Persona 5'' and its related titles, Captain Kidd is the Persona of party member Ryuji Sakamoto, which appears as a skeleton dressed as a stylized pirate riding a ship. *In '' Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag'', the character Mary Read, in order to facilitate her career as a pirate, poses as James Kidd, an illegitimate son of the late William Kidd.See also

References

Citations

Sources

* * *Further reading

Books

* Campbell (1853). ''An Historical Sketch of Robin Hood and Captain Kid''. New York. * Dalton, Sir Cornelius Neale (1911). ''The Real Captain Kidd: A Vindication''. New York: Duffield. * Gilbert, H. (1986). ''The Book of Pirates''. London: Bracken Books. * * Konstam, Angus (2008). ''The Complete History of Piracy''. (Osprey Publishing). * Ritchie, Robert C. (1986). ''Captain Kidd and the War against the Pirates''. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. * Various (2019) ''The Search for Captain Kidd’s Treasure: Early Newspaper Reports, 1836–1859'' (self-published). * Wilkins, Harold T. (1937). ''Captain Kidd and His Skeleton Island''. New York: Liveright Publishing Corp. * Zacks, Richard (2002). ''The Pirate Hunter: The True Story of Captain Kidd''. Hyperion Books. .Articles

Captain Kidd

Pirate's Treasure Buried in the Connecticut River

* ttp://www.piratesinfo.com/biography/biography.php?article_id=36 Biography at piratesinfo.com

Dave's Blog

Blog, observer with the Indiana University expedition to the Quedagh Merchant (ongoing)

National Archives – Article listing Records held concerning Captain Kidd

Arraignment, Tryal and Condemnation of Captain William Kidd

The court documents of the trial of William Kidd, in Early Modern English.

External links

Captain Kidd pub

, What's in Wapping? Local community website {{DEFAULTSORT:Kidd, William 1645 births 1701 deaths 17th-century Scottish people 18th-century Scottish people 17th-century American people 17th-century American criminals 18th-century American people 17th-century pirates American folklore Scottish emigrants to the Thirteen Colonies Executed Scottish people People executed for murder People executed for piracy People executed by Stuart England People from Dundee Military personnel from New York City People from colonial New York People associated with Inverclyde British privateers Scottish people convicted of murder Scottish pirates History of New York City People executed by the Kingdom of England by hanging People from Grand Manan Maritime folklore Murder convictions without a body Mutineers British military personnel of the Nine Years' War Piracy in the Indian Ocean Piracy in the Atlantic Ocean