William John Clarke on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

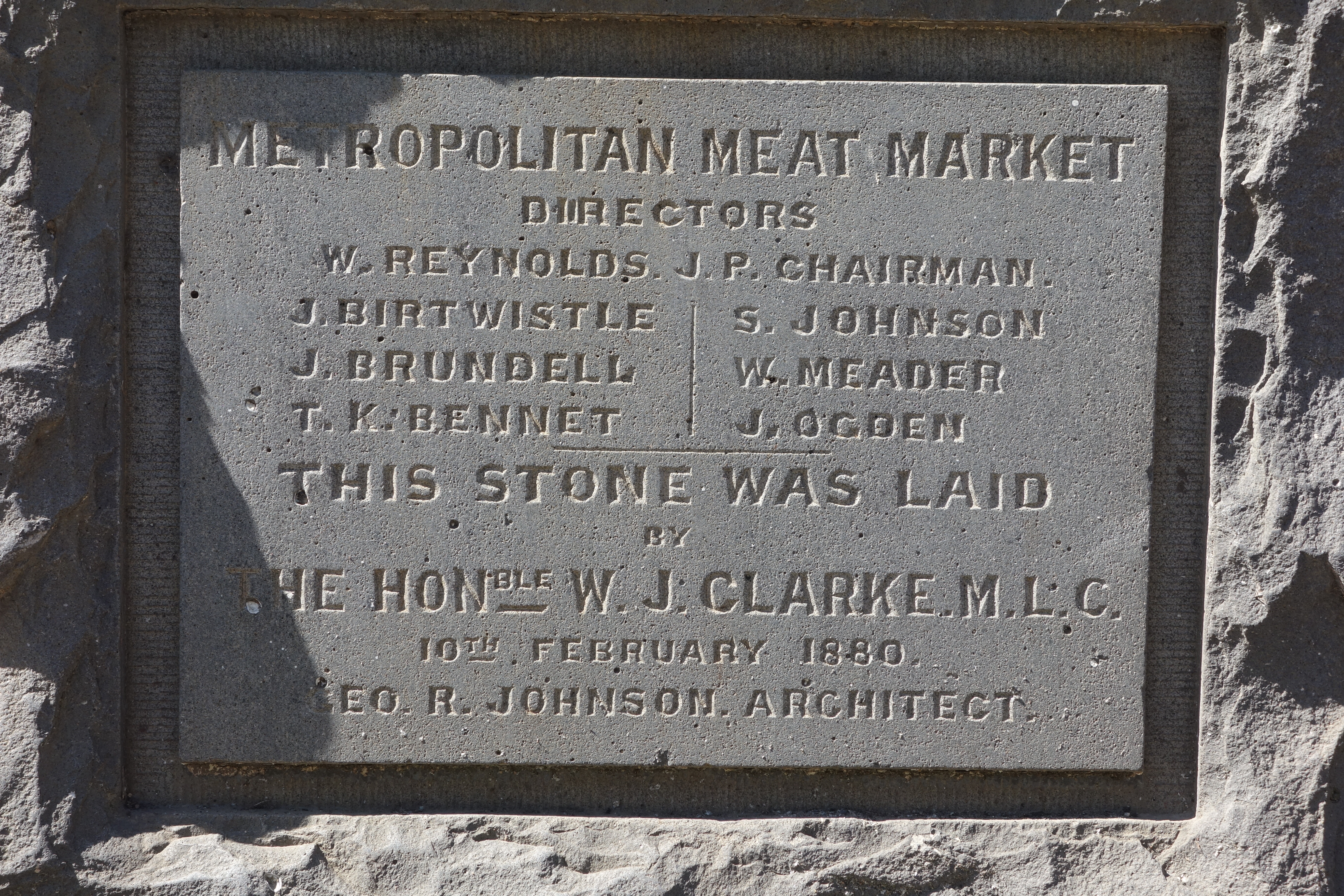

Sir William John Clarke, 1st Baronet (31 March 1831 – 15 May 1897), was an Australian businessman and philanthropist in the

Clarke took some interest in local government and was chairman of the Braybrook Road Board. On the death of his father he found himself with a very large income, much of which he began to use for the benefit of the state. His largest gifts were £10,000 for the building fund of St Paul's cathedral and £7000 for

Clarke took some interest in local government and was chairman of the Braybrook Road Board. On the death of his father he found himself with a very large income, much of which he began to use for the benefit of the state. His largest gifts were £10,000 for the building fund of St Paul's cathedral and £7000 for

Clarke, Sir William John (1831 - 1897)

,

Colony of Victoria

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the '' metropolitan state'' ...

. He was raised to the baronet

A baronet ( or ; abbreviated Bart or Bt) or the female equivalent, a baronetess (, , or ; abbreviation Btss), is the holder of a baronetcy, a hereditary title awarded by the British Crown. The title of baronet is mentioned as early as the 14th ...

age in 1882, the first Victorian to be granted a hereditary honour.

Clarke was born in Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the colonial name of the island of Tasmania used by the British during the European exploration of Australia in the 19th century. A British settlement was established in Van Diemen's Land in 1803 before it became a sepa ...

, the son of the pastoralist William John Turner Clarke

William John Turner Clarke, M.L.C. (20 April 1805 – 13 January 1874), was an Australian politician, member of the Victorian Legislative Council November 1856 to January 1861 and January 1863 to November 1870.

Clarke was born in Somersetshir ...

. He arrived in the Port Phillip District

The Port Phillip District was an administrative division of the Colony of New South Wales from 9 September 1836 until 1 July 1851, when it was separated from New South Wales and became the Colony of Victoria.

In September 1836, NSW Colonial Sec ...

(the future Victoria) in 1850, where he managed many of his father's properties and acquired some of his own. Upon his father's death in 1874, he became the largest landowner in the colony. Clarke was made a baronet for his work as the head of the Melbourne International Exhibition

The Melbourne International Exhibition is the eighth World's fair officially recognised by the Bureau International des Expositions (BIE) and the first official World's Fair in the Southern Hemisphere.

Preparations

After being granted self-go ...

, which brought Australia to international attention. He also served terms as president of the Australian Club

The Australian Club is a private club founded in 1838 and located in Sydney at 165 Macquarie Street. Its membership is men-only and it is the oldest gentlemen's club in the southern hemisphere.

"The Club provides excellent dining facilities, ...

, president of the Victorian Football Association

The Victorian Football League (VFL) is an Australian rules football league in Australia serving as one of the second-tier regional semi-professional competitions which sit underneath the fully professional Australian Football League (AFL). It ...

, and president of the Melbourne Cricket Club

The Melbourne Cricket Club (MCC) is a sports club based in Melbourne, Australia. It was founded in 1838 and is one of the oldest sports clubs in Australia.

The MCC is responsible for management and development of the Melbourne Cricket Ground ...

, and was prominent in yachting and horse racing circles. Clarke gave generously to charitable organisations, and also made significant financial contributions to the Anglican Diocese of Melbourne

The Anglican Diocese of Melbourne is the metropolitan diocese of the Province of Victoria in the Anglican Church of Australia. The diocese was founded from the Diocese of Australia by letters patent of 25 June 1847University of Melbourne

The University of Melbourne is a public research university located in Melbourne, Australia. Founded in 1853, it is Australia's second oldest university and the oldest in Victoria. Its main campus is located in Parkville, an inner suburb nor ...

. He was a member of the Victorian Legislative Council

The Victorian Legislative Council (VLC) is the upper house of the bicameral Parliament of Victoria, Australia, the lower house being the Legislative Assembly. Both houses sit at Parliament House in Spring Street, Melbourne. The Legislative Co ...

from 1878 until 1897, although he was not particularly active in politics.

Early life

Clarke was born at Lovely Banks (one of his father's properties, nearJericho

Jericho ( ; ar, أريحا ; he, יְרִיחוֹ ) is a Palestinian city in the West Bank. It is located in the Jordan Valley, with the Jordan River to the east and Jerusalem to the west. It is the administrative seat of the Jericho Gove ...

) in Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the colonial name of the island of Tasmania used by the British during the European exploration of Australia in the 19th century. A British settlement was established in Van Diemen's Land in 1803 before it became a sepa ...

(later renamed Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

), the eldest of three sons of William John Turner Clarke

William John Turner Clarke, M.L.C. (20 April 1805 – 13 January 1874), was an Australian politician, member of the Victorian Legislative Council November 1856 to January 1861 and January 1863 to November 1870.

Clarke was born in Somersetshir ...

and his wife Eliza (''née'' Dowling). Clarke senior was an early Tasmanian colonist, who acquired large pastoral properties in Tasmania, Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Victoria (Australia), a state of the Commonwealth of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, provincial capital of British Columbia, Canada

* Victoria (mythology), Roman goddess of Victory

* Victoria, Seychelle ...

, South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories ...

and New Zealand and settled afterwards in Victoria at Rupertswood

Rupertswood is a mansion and country estate located in Sunbury, 50km north-northwest of Melbourne in Victoria, Australia. It is well known as the birthplace of The Ashes urn which was humorously presented to English cricket captain Ivo Bligh to ...

, Sunbury.

Clarke first arrived in Victoria in 1850, when he spent a couple of years in the study of sheep farming on his father's Dowling Forest station, and afterwards in the management of the Woodlands station on the Wimmera. For the next ten years he resided in Tasmania, working the Norton-Mandeville estate in conjunction with his brother, Joseph Clarke.

Career

Trinity College Trinity College may refer to:

Australia

* Trinity Anglican College, an Anglican coeducational primary and secondary school in , New South Wales

* Trinity Catholic College, Auburn, a coeducational school in the inner-western suburbs of Sydney, New ...

, Melbourne University

The University of Melbourne is a public research university located in Melbourne, Australia. Founded in 1853, it is Australia's second oldest university and the oldest in Victoria. Its main campus is located in Parkville, an inner suburb nor ...

. In 1862 Clarke stood against George Higinbotham

George Higinbotham (19 April 1826 – 31 December 1892) was a politician and was a Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Victoria, which is the highest ranking court in the Australian colony (and later, State) of Victoria.

Early life

George H ...

in the Brighton

Brighton () is a seaside resort and one of the two main areas of the City of Brighton and Hove in the county of East Sussex, England. It is located south of London.

Archaeological evidence of settlement in the area dates back to the Bronze A ...

by-election for the Victorian Legislative Assembly

The Victorian Legislative Assembly is the lower house of the bicameral Parliament of Victoria in Australia; the upper house being the Victorian Legislative Council. Both houses sit at Parliament House in Spring Street, Melbourne.

The presiding ...

, but was not elected. He was elected a member of the Victorian Legislative Council

The Victorian Legislative Council (VLC) is the upper house of the bicameral Parliament of Victoria, Australia, the lower house being the Legislative Assembly. Both houses sit at Parliament House in Spring Street, Melbourne. The Legislative Co ...

for the Southern Province in September 1878, but never took a prominent part in politics.

In 1862 Clarke assumed the management of his father's concerns in Victoria, and on the latter's death in 1874 succeeded to his estates in that colony. In the same year he was appointed president of the commissioners of the Melbourne international exhibition

The Melbourne International Exhibition is the eighth World's fair officially recognised by the Bureau International des Expositions (BIE) and the first official World's Fair in the Southern Hemisphere.

Preparations

After being granted self-go ...

which was opened on 1 October 1880. In 1882 he gave £3,000 to found a scholarship in the Royal College of Music

The Royal College of Music is a music school, conservatoire established by royal charter in 1882, located in South Kensington, London, UK. It offers training from the Undergraduate education, undergraduate to the Doctorate, doctoral level in a ...

.

For many years Clarke bore the full expense of the Rupertswood battery of horse artillery at Sunbury, Victoria

Sunbury () is a suburb in Melbourne, Victoria (Australia), Victoria, Australia, north-west of Melbourne's Melbourne central business district, Central Business District, located within the City of Hume Local government areas of Victoria, local ...

.

Amongst Sir William Clarke's other public donations are the gift of £2000 to the Indian Famine Relief Fund, of £10,000 towards building the Anglican Cathedral at Melbourne, and of £7000 to Trinity College, Melbourne University.

Clarke also took interest in various forms of sport, his yacht, the ''Janet'', won several races, but he was not very successful on the turf; the most important race he won being the V.R.C. Oaks. He was the inaugural president of the Victorian Football Association

The Victorian Football League (VFL) is an Australian rules football league in Australia serving as one of the second-tier regional semi-professional competitions which sit underneath the fully professional Australian Football League (AFL). It ...

, presiding from 1877 until 1882. He was the patron of many agricultural societies and did much to improve the breed of cattle in Victoria. Before the Victorian department of agriculture was established he provided a laboratory for Ralph Waldo Emerson MacIvor,

and paid him to lecture on agricultural chemistry in farming centres. In 1886, he was a member of the Victorian commission to the Colonial and Indian exhibition, and in the same year Cambridge gave him the honorary degree of LL.D.

Clarke was a very prominent Victorian Freemason and was elected provincial grand master of the Irish Constitution in 1881 and then district grand master of both the Scottish and English Constitutions in 1884. In 1889 he became the very first Most Worshipful Grand Master of the United Grand Lodge of Victoria, an amalgamation of the three bodies that had operated at that time under their own constitutions. In 1885 he had largely financed the building of the Freemasons' Hall at 25 Collins Street.

Later life

In Clarke's later years, although his interests lay principally in the country, he lived at his town house Cliveden in East Melbourne. He died suddenly at Melbourne on 15 May 1897. He was created abaronet

A baronet ( or ; abbreviated Bart or Bt) or the female equivalent, a baronetess (, , or ; abbreviation Btss), is the holder of a baronetcy, a hereditary title awarded by the British Crown. The title of baronet is mentioned as early as the 14th ...

in 1882, by Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 21 ...

in recognition for his many donations and for his presiding over the Melbourne International Exhibition

The Melbourne International Exhibition is the eighth World's fair officially recognised by the Bureau International des Expositions (BIE) and the first official World's Fair in the Southern Hemisphere.

Preparations

After being granted self-go ...

in 1880.

He married twice, firstly in 1860 to Mary Walker, daughter of the Tasmanian businessman and politician John Walker. He was widowed in April 1871, and in January 1873 remarried to Janet Marian Snodgrass, the daughter of the Victorian pastoralist and politician Peter Snodgrass

Peter Snodgrass (29 September 1817 – 25 November 1867) was a pastoralist and politician in colonial Victoria, a member of the Victorian Legislative Council, and later, of the Victorian Legislative Assembly.

Snodgrass was born in Portugal an ...

. He had two sons and two daughters by his first wife, and another four sons and four daughters by his second; he was survived by Janet and nine of his children.

Clarke was a household name in Victoria. He made a few large donations but his help could constantly be relied on by hospitals, charitable institutions, and agricultural and other societies. He divided one of his estates into small holdings and was a model landlord, and he showed much foresight in allying science with agriculture by employing MacIvor as a lecturer. His second wife, Janet, who had been associated with him in philanthropic movements, kept up her interest in them, especially in all matters relating to women, until her death on 28 April 1909. One of their sons, Sir Francis Grenville Clarke

Sir Francis Grenville Clarke (14 March 1879 – 13 February 1955) was an Australian politician.

He was born in Sunbury to grazier William John Clarke (later Sir William Clarke, 1st Baronet) and Janet Marion Snodgrass. His grandfather Wi ...

, went into politics and was a member of several Victorian ministries. He became president of the Legislative Council in 1923 and held that position for almost 20 years and was created K.B.E. in 1926.

His son Rupert succeeded him as the 2nd Baronet. The baronetcy of Clarke of Rupertswood is one of only two active hereditary titles in an Australian family.

His second son, Ernest Edward Dowling Clarke (1869–1941), was a noted racehorse owner, closely associated with trainer James Scobie

James Scobie (29 November 1826 – 7 October 1854) was a Scottish gold digger murdered at Ballarat, Victoria, Australia. His death was associated with a sequence of events which led to the Eureka Rebellion.

At the later Supreme Court trial in ...

.

Footnotes

References

* *Sylvia Morrissey,Clarke, Sir William John (1831 - 1897)

,

Australian Dictionary of Biography

The ''Australian Dictionary of Biography'' (ADB or AuDB) is a national co-operative enterprise founded and maintained by the Australian National University (ANU) to produce authoritative biographical articles on eminent people in Australia's ...

, Volume 3, MUP, 1969, pp 422–424.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Clarke, William, Sir, 1st Baronet

1831 births

1897 deaths

Australian philanthropists

Australian recipients of a British baronetcy

Members of the Victorian Legislative Council

VFA/VFL administrators

Australian Freemasons

Masonic Grand Masters

Baronets in the Baronetage of the United Kingdom

19th-century Australian politicians

People from Tasmania

Australian pastoralists

19th-century philanthropists

19th-century Australian businesspeople

Clarke baronets

Australian people of English descent