William Henry Sheppard (mayor) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

William Henry Sheppard (March 8, 1865 – November 25, 1927) was one of the earliest

Sheppard and Lapsley's activities in Africa were enabled by the very man whose atrocities Sheppard would later attempt to expose. The pair traveled to

Sheppard and Lapsley's activities in Africa were enabled by the very man whose atrocities Sheppard would later attempt to expose. The pair traveled to

In the late 19th century,

In the late 19th century,

Sheppard's efforts contributed to the contemporary debate on European colonialism and imperialism in the region, particularly among the African-American community. However, historians have noted that he has traditionally received little recognition for his contributions.

Over the course of his journeys, Sheppard amassed a sizable collection of Kuba art, much of which he donated to his alma mater,

Sheppard's efforts contributed to the contemporary debate on European colonialism and imperialism in the region, particularly among the African-American community. However, historians have noted that he has traditionally received little recognition for his contributions.

Over the course of his journeys, Sheppard amassed a sizable collection of Kuba art, much of which he donated to his alma mater,

"Black Livingstone"

'' National Geographic News'', March 1, 2002 * Marilyn Lewis

"Jewel of the Kingdom: William Sheppard"

''Mission Frontiers'' magazine, unknown date (hosted by urbana.org)

Papers of William H. Sheppard

from the

A review of two biographies

of Sheppard, from the ''North Star'', a journal of African-American religious history. {{DEFAULTSORT:Sheppard, William Henry 1865 births 1927 deaths 19th-century African-American people Activists against atrocities in the Congo Free State African-American missionaries American ethnologists American expatriates in the Congo Free State American Presbyterian missionaries Congo Free State people Hampton University alumni People from Waynesboro, Virginia Presbyterian ministers Presbyterian missionaries Presbyterian missionaries in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Stillman College alumni

African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

s to become a missionary

A missionary is a member of a Religious denomination, religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Tho ...

for the Presbyterian Church

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

. He spent 20 years in Africa, primarily in and around the Congo Free State

''(Work and Progress)

, national_anthem = Vers l'avenir

, capital = Vivi Boma

, currency = Congo Free State franc

, religion = Catholicism (''de facto'')

, leader1 = Leopo ...

, and is best known for his efforts to publicize the atrocities committed against the Kuba and other Congolese peoples by King Leopold II

* german: link=no, Leopold Ludwig Philipp Maria Viktor

, house = Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

, father = Leopold I of Belgium

, mother = Louise of Orléans

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Brussels, Belgium

, death_date = ...

's ''Force Publique

The ''Force Publique'' (, "Public Force"; nl, Openbare Weermacht) was a gendarmerie and military force in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 1885 (when the territory was known as the Congo Free State), through the period of ...

''.

Sheppard's efforts contributed to the contemporary debate on European colonialism

The historical phenomenon of colonization is one that stretches around the globe and across time. Ancient and medieval colonialism was practiced by the Phoenicians, the Greeks, the Turkish people, Turks, and the Arabs.

Colonialism in the mode ...

and imperialism in the region, particularly among those of the African-American community.Füllberg-Stolberg (1999), p. 215. However, it has been noted that he traditionally received little attention in literature on the subject.Füllberg-Stolberg (1992), pp. 225–226.

Early life and education

Sheppard was born in Waynesboro, Virginia, on March 8, 1865, to William Henry Sheppard, Sr. and Fannie Frances Sheppard (née Martin), a free " dark mulatto", a month before the end of theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

. No records exist to confirm William Sr.'s status as a slave or freedman, but it has been speculated that he may have been among the slaves forced to serve the Confederacy as Union troops marched upon the South. William Sr. was a barber, and the family has been described as the closest to middle class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. Commo ...

that blacks could have achieved given the time and place.Kennedy (2002), pp. 7–10.

At age twelve, William Jr. became a stable boy

A groom or stable boy (stable hand, stable lad) is a person who is responsible for some or all aspects of the management of horses and/or the care of the stables themselves. The term most often refers to a person who is the employee of a stable ...

for a white family several miles away while continuing to attend school; he remembered his two-year stay fondly and maintained written correspondence with the family for many years. Sheppard next worked as a waiter to put himself through the newly created Hampton Institute, where Booker T. Washington

Booker Taliaferro Washington (April 5, 1856November 14, 1915) was an American educator, author, orator, and adviser to several presidents of the United States. Between 1890 and 1915, Washington was the dominant leader in the African-American c ...

was among his instructors in a program that allowed students to work during the day and attend classes at night. A significant influence on his appreciation for native cultures was the "Curiosity Room", in which the school's founder maintained a collection of Native Hawaiian and Native American works of art. Later in life he would collect artifacts from the Congo, specifically those of the Kuba, and bring them back for this room, as evidenced by his letters home, such as " was on the first of September, 1890 that William H. Sheppard addressed a letter to General Samuel Armstrong, Hampton, From Stanley Pool, Africa, that he had many artifacts, spears, idols, etc., and he was '...saving them for the Curiosity Room at Hampton'".Taken from "The Report of the College Museum of Hampton Institute for 1966", reprinted by Cureau (1982), p. 341.

After graduation, Sheppard was recommended for admittance to Tuscaloosa Theological Institute, present-day Stillman College in Tuscaloosa, Alabama

Tuscaloosa ( ) is a city in and the seat of Tuscaloosa County in west-central Alabama, United States, on the Black Warrior River where the Gulf Coastal and Piedmont plains meet. Alabama's fifth-largest city, it had an estimated population of 1 ...

, which in 1959 dedicated its library in Sheppard's honor.) He met Lucy Gantt near the end of his time at Tuscaloosa Theological Institute, and the two became engaged but did not marry until ten years later. Sheppard developed an interest in preaching in Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

, and was supported in this endeavor by Charles Stillman

Charles Stillman (November 4, 1810 – December 18, 1875) was the founder of Brownsville, Texas, and was part owner of a successful river boat company on the Rio Grande.

Early life

He was born in Wethersfield, Connecticut, United States, ...

, the institute's founder. The Southern Presbyterian Church, however, had yet to establish its mission in the Congo

Congo or The Congo may refer to either of two countries that border the Congo River in central Africa:

* Democratic Republic of the Congo, the larger country to the southeast, capital Kinshasa, formerly known as Zaire, sometimes referred to a ...

.

Career

Sheppard was ordained in 1888 and served as pastor at a church inAtlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,715 ...

, but did not adapt well to the life of an urban black in a heavily segregated area of the Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

. After two years of writing to the Presbyterian Foreign Missionary Board in Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

, inquiring about starting a mission in Africa. Frustrated by the vague rationale in the rejection letters he received, Sheppard took a train to Baltimore, where he asked the chairman in person and was politely told that the board would not send a black man to Africa without a white supervisor.

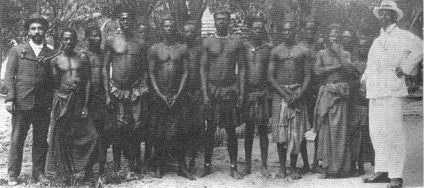

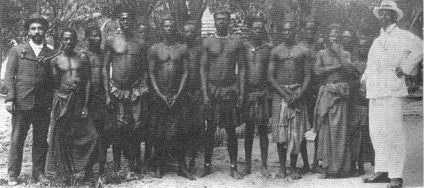

Samuel Lapsley, an eager but inexperienced white man from a wealthy family, intervened to offer his support, enabling Sheppard's journey to Africa. They "inaugurated the unique principle of sending out together, with equal ecclesiastical rights and, as far as possible, in equal numbers, white and colored workers".

Mission with Lapsley

Sheppard and Lapsley's activities in Africa were enabled by the very man whose atrocities Sheppard would later attempt to expose. The pair traveled to

Sheppard and Lapsley's activities in Africa were enabled by the very man whose atrocities Sheppard would later attempt to expose. The pair traveled to London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

in 1890 en route to the Congo; while there, Lapsley met General Henry Shelton Sanford, an American ally of King Leopold II

* german: link=no, Leopold Ludwig Philipp Maria Viktor

, house = Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

, father = Leopold I of Belgium

, mother = Louise of Orléans

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Brussels, Belgium

, death_date = ...

and friend of a friend of Lapsley's father. Sanford promised to do "everything in his power" to help the pair, even arranging an audience with King Leopold when Lapsley visited him in Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

. Neither the secular Sanford nor the Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

Leopold were interested in the Presbyterians

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

' work. Leopold was eager to make inroads into his newly acquired territory, both to begin the process of "civilizing" the natives and to legitimize his rule. The missionaries were, however, oblivious of Leopold's motives.

The pair made their way to Leopoldville, and Sheppard's own writings as well as Lapsley's letters home suggest Sheppard viewed the natives in a markedly different manner from other foreigners. Sheppard was considered as foreign as Lapsley and even acquired the nickname "Mundele N'dom", or "black white man". Despite being of African descent, Sheppard believed in many of the stereotypes of the time regarding Africa and its inhabitants, such as the idea that African natives were uncivilized or savage.Cureau (1982), p. 344. Very quickly though his views changed, as exemplified by a journal entry:

The natives' resistance to conversion bothered Lapsley more than Sheppard, as Sheppard viewed himself more as an explorer than a missionary. While Lapsley was on a trip to visit fellow missionary–explorer George Grenfell

George Grenfell (21 August 1849, in Sancreed, Cornwall – 1 July 1906, in Basoko, Congo Free State (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) was a Cornish missionary and explorer.

Early years

Grenfell was born at Sancreed, near Penzan ...

, Sheppard became familiar with the natives' hunting techniques and language. He even helped to avert a famine

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food, caused by several factors including war, natural disasters, crop failure, Demographic trap, population imbalance, widespread poverty, an Financial crisis, economic catastrophe or government policies. Th ...

by slaying 36 hippos. Sheppard contracted malaria 22 times in his first two years in Africa.

Contact with the Kuba

Sheppard became versed in theKuba language

Kuba (Likuba, Kyba) is a Bantu language of Kasai, Democratic Republic of Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (french: République démocratique du Congo (RDC), colloquially "La RDC" ), informally Congo-Kinshasa, DR Congo, the DRC ...

and culture. In 1892, he took a team of men to the edge of the Kuba Kingdom. He originally planned to ask for directions to the next village under the guise of purchasing supplies, but the chief of the village only allowed one of his men to go. Sheppard used a variety of tricks to make his way further into the kingdom, including having a scout follow a group of traders and, most famously, eating so many eggs that the townspeople could no longer supply him and his scout was able to gain access to the next village to find more eggs. Eventually, however, he encountered villagers that would allow him to go no further. While Sheppard was formulating a plan, the king's son, Prince N'toinzide, arrived and arrested Sheppard and his men for trespassing.

King Kot aMweeky, rather than executing Sheppard, told the village that Sheppard was his deceased son. King aMweeky declared Sheppard "Bope Mekabe", which spared the lives of Sheppard and his men.Kennedy (2002), p. 89. This was a political move on the part of the king; in danger of being overthrown, he encouraged interest in the strangers to direct attention away from himself. During his stay in the village, Sheppard collected artifacts from the people and he eventually secured permission for a Presbyterian mission. The king allowed him to leave on the condition that he return in one year. He would be unable to do so for several years, however, by which time Kot aMweeky had been overthrown by Mishaape, the leader of a rival clan.

Documentation of Congo Free State atrocities

In the late 19th century,

In the late 19th century, King Leopold II

* german: link=no, Leopold Ludwig Philipp Maria Viktor

, house = Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

, father = Leopold I of Belgium

, mother = Louise of Orléans

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Brussels, Belgium

, death_date = ...

started to receive criticism for his treatment of the natives in Congo Free State. In the United States, the main outlet of this criticism was the Presbyterian church. In 1891, Sheppard became involved with William Morrison after Lapsley's death. They would report the crimes they saw, and later, with the help of Roger Casement

Roger David Casement ( ga, Ruairí Dáithí Mac Easmainn; 1 September 1864 – 3 August 1916), known as Sir Roger Casement, CMG, between 1911 and 1916, was a diplomat and Irish nationalist executed by the United Kingdom for treason during Worl ...

, would form the Congo Reform Association (CRA), one of the world's first humanitarian organizations.Nzongola-Ntalaja (2002), p. 24.

In January 1900, ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' published a report that said 14 villages had been burned and 90 or more of the local people killed in the Bena Kamba

Bena Kamba is a community on the Lomami River in Maniema province of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The Limami, which flows northward parallel to the Lualaba or Upper Congo River, is navigable as far south as Bena Kamba. From there, it is ...

country by Zappo Zap

The Zappo Zap were a group of Songye people from the eastern Kasaï region in what today is the Democratic Republic of the Congo. They acted as allies of the Congo Free State authorities, while trading in ivory, rubber and slaves.

In 1899 they were ...

warriors sent to collect taxes by the Congo Free State

''(Work and Progress)

, national_anthem = Vers l'avenir

, capital = Vivi Boma

, currency = Congo Free State franc

, religion = Catholicism (''de facto'')

, leader1 = Leopo ...

administration. The report was based on letters from Southern Presbyterian missionaries Rev. L. C. Vass and Rev. H. P. Hawkins stationed at Luebo

Luebo or Lwebo is a town (officially a commune) of Kasai Province in south-central Democratic Republic of the Congo. It is also the seat of the territory

A territory is an area of land, sea, or space, particularly belonging or connected to ...

and the subsequent investigation by Sheppard who visited the Zappo Zaps' camp.

Apparently taken for a government official, he was openly shown the bodies of many of the victims.

Sheppard saw evidence of cannibalism

Cannibalism is the act of consuming another individual of the same species as food. Cannibalism is a common ecological interaction in the animal kingdom and has been recorded in more than 1,500 species. Human cannibalism is well documented, b ...

.

He counted 81 right hands that had been cut off and were being dried before being taken to show the State officers what the Zappo Zaps had achieved. He also found 60 women confined in a pen. Sheppard documented his findings using a Kodak camera

The Eastman Kodak Company (referred to simply as Kodak ) is an American public company that produces various products related to its historic basis in analogue photography. The company is headquartered in Rochester, New York, and is incorpor ...

, taking a picture of three mutilated men and one of the captive women. The massacre caused an uproar against Dufour and the Congo Free State itself.

When Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, entrepreneur, publisher, and lecturer. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has p ...

published his ''King Leopold's Soliloquy

''King Leopold's Soliloquy'' is a 1905 pamphlet by American author Mark Twain. Its subject is King Leopold's rule over the Congo Free State. A work of political satire harshly condemnatory of his actions, it ostensibly recounts a fictional monol ...

'' five years later, he mentioned Sheppard by name and referred to his account of the massacre.

In January 1908, Sheppard published a report on colonial abuses in the American Presbyterian Congo Mission (APCM) newsletter, and both he and Morrison were sued for libel against the Kasai Rubber Company (Compagnie de Kasai), a Belgian rubber contractor in the area. The case went to court in September 1909, and the two missionaries were supported by the CRA, American Progressives

Progressivism in the United States is a political philosophy and reform movement in the United States advocating for policies that are generally considered left-wing, left-wing populist, libertarian socialist, social democratic, and environmentalis ...

, and their lawyer, Emile Vandervelde

Emile Vandervelde (25 January 1866 – 27 December 1938) was a Belgian socialist politician. Nicknamed "the boss" (''le patron''), Vandervelde was a leading figure in the Belgian Labour Party (POB–BWP) and in international socialism.

Career

Emi ...

, who was a Belgian socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

. The judge acquitted Sheppard on the premise that his editorial had not named the major company, but smaller charter companies instead. However, it is likely that the case was decided in favor of Sheppard as a result of international politics; the U.S., socially supportive of missionaries, had questioned the validity of King Leopold II's rule in the Congo. Morrison had been acquitted earlier on a technicality.

Sheppard's reports often portrayed actions by the state that broke laws set by the European nations. Many of the documented cases of cruelty or violence were in direct violation of the Berlin Act of 1885, which gave Leopold II control over the Congo as long as he "care for the improvements of their conditions of their moral and material well-being" and "help din suppressing slavery."

Legacy

Sheppard's efforts contributed to the contemporary debate on European colonialism and imperialism in the region, particularly among the African-American community. However, historians have noted that he has traditionally received little recognition for his contributions.

Over the course of his journeys, Sheppard amassed a sizable collection of Kuba art, much of which he donated to his alma mater,

Sheppard's efforts contributed to the contemporary debate on European colonialism and imperialism in the region, particularly among the African-American community. However, historians have noted that he has traditionally received little recognition for his contributions.

Over the course of his journeys, Sheppard amassed a sizable collection of Kuba art, much of which he donated to his alma mater, Hampton University

Hampton University is a private, historically black, research university in Hampton, Virginia. Founded in 1868 as Hampton Agricultural and Industrial School, it was established by Black and White leaders of the American Missionary Association af ...

, which has his collection on display at the Hampton University Museum

Founded in 1868 on the campus of Hampton University, the Hampton University Museum is the oldest African-American museum in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) ...

. He was possibly the first African-American collector of African art.Cureau (1982), pp. 45–48. This art collection was notable because it "acquired the art objects in Africa, from Africans at all levels in their society...in the context of their daily existence" and, as a whole, Kuba art is considered "one of the most highly developed of African visual art forms...." The collection, as a whole, is quite large; from the time of his arrival to Congo Free State in 1890 until his final departure 20 years later, in 1910, Sheppard was collecting art and artifacts from the cultures around him.

Sheppard's collection was also useful to ethnologist

Ethnology (from the grc-gre, ἔθνος, meaning 'nation') is an academic field that compares and analyzes the characteristics of different peoples and the relationships between them (compare cultural, social, or sociocultural anthropology) ...

s of the time because the Kuba culture was not well known by the outside world, even by those well-versed with African studies. For example, the collection does not feature a large number of carved human figures or any figurine that could be connected to a deity of some sort. That could be taken as evidence that the Kuba either had no religion or had one that was not outwardly expressed through art.Cureau (1982) p. 344. On the issue of the collection's scientific value, Jane E. Davis of the '' Southern Workman'' journal wrote that "it not only meets the requirements of the ethnologists, but those of the artist as well. Already it has been used by scientists to establish the origins of the culture of the Bakuba tribe."

See also

* George Washington Williams *Presbytery of Sheppards and Lapsley

The Presbytery of Sheppards and Lapsley is an administrative district of the Presbyterian Church (USA) which comprises some 94 churches in central Alabama. The Presbytery of Sheppards and Lapsley is one of three presbyteries located in Alabama, an ...

Footnotes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* * D. L. Parsell"Black Livingstone"

'' National Geographic News'', March 1, 2002 * Marilyn Lewis

"Jewel of the Kingdom: William Sheppard"

''Mission Frontiers'' magazine, unknown date (hosted by urbana.org)

Papers of William H. Sheppard

from the

Presbyterian Historical Society

The Presbyterian Historical Society (PHS) is the oldest continuous denominational historical society in the United States.Smylie, James H. 1996. ''A Brief History of the Presbyterians.'' Louisville, Kentucky: Geneva Press. Its mission is to col ...

A review of two biographies

of Sheppard, from the ''North Star'', a journal of African-American religious history. {{DEFAULTSORT:Sheppard, William Henry 1865 births 1927 deaths 19th-century African-American people Activists against atrocities in the Congo Free State African-American missionaries American ethnologists American expatriates in the Congo Free State American Presbyterian missionaries Congo Free State people Hampton University alumni People from Waynesboro, Virginia Presbyterian ministers Presbyterian missionaries Presbyterian missionaries in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Stillman College alumni