William Hazlitt (minister) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

William Hazlitt (18 April 1737 – 16 July 1820) was a Unitarian minister and author, and the father of the Romantic essayist and social commentator of the same name.Wu 2007. He was an important figure in eighteenth-century English and American Unitarianism, and had a major influence on his son's work.

Hazlitt was born to

Hazlitt was born to

Hazlitt had an important influence on James Freeman's conversion of the

Hazlitt had an important influence on James Freeman's conversion of the

Despite achieving some success as a writer, Hazlitt was unable to secure a permanent post, and in 1786 he returned to England. After failing to obtain a steady income in London, Hazlitt settled with his family at

Despite achieving some success as a writer, Hazlitt was unable to secure a permanent post, and in 1786 he returned to England. After failing to obtain a steady income in London, Hazlitt settled with his family at

accessed 25 Nov 2011

*

A Bibliography of the Writings of William Hazlitt (1737–1820)

(PDF)

Obituary in the Monthly Repository

(1820) {{DEFAULTSORT:Hazlitt, William 1737 births 1820 deaths People from County Tipperary 18th-century Unitarian clergy Irish Unitarians William Hazlitt Alumni of the University of Glasgow Irish non-subscribing Presbyterian ministers

Biography

Early life

Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

parents at Shronell

Shronell, Shrone Hill, or Shronel () is a civil parish and townland near the villages of Lattin and Emly in County Tipperary, Ireland. It is situated 3 miles southwest of Tipperary town on the R515 regional road.

Name

The word "Shronell" ...

, County Tipperary

County Tipperary ( ga, Contae Thiobraid Árann) is a county in Ireland. It is in the province of Munster and the Southern Region. The county is named after the town of Tipperary, and was established in the early 13th century, shortly after th ...

, in Ireland, and was educated at a grammar school. He matriculated

Matriculation is the formal process of entering a university, or of becoming eligible to enter by fulfilling certain academic requirements such as a matriculation examination.

Australia

In Australia, the term "matriculation" is seldom used now. ...

at the University of Glasgow

, image = UofG Coat of Arms.png

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of arms

Flag

, latin_name = Universitas Glasguensis

, motto = la, Via, Veritas, Vita

, ...

in 1756, where he was taught by Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptized 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the thinking of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as "The Father of Economics"——— ...

, Joseph Black

Joseph Black (16 April 1728 – 6 December 1799) was a Scottish physicist and chemist, known for his discoveries of magnesium, latent heat, specific heat, and carbon dioxide. He was Professor of Anatomy and Chemistry at the University of Glas ...

and James Watt

James Watt (; 30 January 1736 (19 January 1736 OS) – 25 August 1819) was a Scottish inventor, mechanical engineer, and chemist who improved on Thomas Newcomen's 1712 Newcomen steam engine with his Watt steam engine in 1776, which was fun ...

. Hazlitt was exposed to a range of controversial religious and philosophical views while at university, and it is possible that he converted to Unitarianism at this time. After graduating he became a chaplain to Sir Conyers Jocelyn at Hyde Hall, Sawbridgeworth

Sawbridgeworth is a town and civil parish in Hertfordshire, England, close to the border with Essex. It is east of Hertford and north of Epping. It is the northernmost part of the Greater London Built-up Area.

History

Prior to the Norman ...

, Hertfordshire

Hertfordshire ( or ; often abbreviated Herts) is one of the home counties in southern England. It borders Bedfordshire and Cambridgeshire to the north, Essex to the east, Greater London to the south, and Buckinghamshire to the west. For govern ...

, and then worked as a minister at Wisbech

Wisbech ( ) is a market town, inland Port of Wisbech, port and civil parish in the Fenland District, Fenland district in Cambridgeshire, England. In 2011 it had a population of 31,573. The town lies in the far north-east of Cambridgeshire, bord ...

. In 1766 he married Grace Loftus, before moving to Marshfield in Gloucestershire. In the same year he commenced his literary career, when Benjamin Davenport and Joseph Johnson Joseph Johnson may refer to:

Entertainment

*Joseph McMillan Johnson (1912–1990), American film art director

*Smokey Johnson (1936–2015), New Orleans jazz musician

* N.O. Joe (Joseph Johnson, born 1975), American musician, producer and songwrit ...

published Hazlitt's ''Sermon on Human Mortality''.Wu 2006, p. 222.

Preaching in England and Ireland

In 1770 William and Grace Hazlitt, along with their sonsJohn

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second ...

and Loftus, moved to Maidstone

Maidstone is the largest Town status in the United Kingdom, town in Kent, England, of which it is the county town. Maidstone is historically important and lies 32 miles (51 km) east-south-east of London. The River Medway runs through the c ...

in Kent. Soon after their arrival, their son Loftus, only two and a half years old, died. A daughter, Margaret, was born in December. During this period Hazlitt maintained ties with figures such as Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley (; 24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, natural philosopher, separatist theologian, grammarian, multi-subject educator, and liberal political theorist. He published over 150 works, and conducted exp ...

, Richard Price

Richard Price (23 February 1723 – 19 April 1791) was a British moral philosopher, Nonconformist minister and mathematician. He was also a political reformer, pamphleteer, active in radical, republican, and liberal causes such as the French ...

and Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

, and was an active writer, contributing to Priestley's ''Theological Repository

The ''Theological Repository'' was a periodical founded and edited from 1769 to 1771 by the eighteenth-century British polymath Joseph Priestley. Although ostensibly committed to the open and rational inquiry of theological questions, the journ ...

'' under the pseudonyms "Philalethes" and "Rationalis", and publishing five religious volumes. His work provoked a substantial body of writing by other authors. In 1778 his son William

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...

was born.

Hazlitt's writings at this time included pamphlets entitled ''The Methodists Vindicated'' (1771) and ''Human Authority in Matters of Faith Repugnant to Christianity'' (1774). Stephen Burley, who has investigated Hazlitt's authorship of these works, describes Hazlitt's position in ''Methodists Vindicated'' as follows:

He sets out to subvert preconceptions about social and ecclesiastical hierarchies in a sweeping attack on the legitimacy of the Established Church and its clergy. He argues for a distinctly egalitarian faith which comprehends both men and women, rich and poor.Hazlitt was, in the words of

Duncan Wu

Duncan Wu (born 3 November 1961 in Woking, Surrey) is a British academic and biographer.

Biography

Wu received his D.Phil from Oxford University. From 2000-2008, he was Professor of English Language and Literature at St Catherine's College, ...

, "essentially a Socinian

Socinianism () is a nontrinitarian belief system deemed heretical by the Catholic Church and other Christian traditions. Named after the Italian theologians Lelio Sozzini (Latin: Laelius Socinus) and Fausto Sozzini (Latin: Faustus Socinus), uncle ...

" in his religious beliefs. His writings criticise the persistence of Catholic doctrines in the Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

church which, in Hazlitt's view, have no basis in scripture. As a Unitarian, he also rejected the Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God the F ...

, and instead offered a form of religious faith "founded in reason". The rejection of the established church

A state religion (also called religious state or official religion) is a religion or creed officially endorsed by a sovereign state. A state with an official religion (also known as confessional state), while not secular, is not necessarily a t ...

, and of religious hierarchies, was also central to Hazlitt's doctrine. He even called on parliament to adopt his form of Unitarianism, revealing the extent to which his religious beliefs had a politically radical edge. The literary critic Tom Paulin

Thomas Neilson Paulin (born 25 January 1949 in Leeds, England) is a Northern Irish poet and critic of film, music and literature. He lives in England, where he was the G. M. Young Lecturer in English Literature at Hertford College, Oxford.

Earl ...

has also highlighted Hazlitt's political radicalism, associating him with the " Real Whig" political tendency that developed from the commonwealthmen

The Commonwealth men, Commonwealth's men, or Commonwealth Party were highly outspoken British Protestant religious, political, and economic reformers during the early 18th century. They were active in the movement called the Country Party. They ...

of the seventeenth century, and which was characterised by republican beliefs. A friend of Hazlitt described him as "an ultra-Dissenter

A dissenter (from the Latin ''dissentire'', "to disagree") is one who dissents (disagrees) in matters of opinion, belief, etc.

Usage in Christianity

Dissent from the Anglican church

In the social and religious history of England and Wales, and ...

, and in politics a republican".

In 1780 Hazlitt returned to Ireland,Wardle 1971, p. 6. ministering to a congregation at Bandon in County Cork

County Cork ( ga, Contae Chorcaí) is the largest and the southernmost county of Ireland, named after the city of Cork, the state's second-largest city. It is in the province of Munster and the Southern Region. Its largest market towns are ...

for three years. Another son, Thomas, was born soon after the Hazlitts' arrival in 1780; he survived only a few weeks. A daughter, Harriet, was born in late 1781 or early 1782. During this time Hazlitt exposed in the press the abuse of American prisoners of war at Kinsale

Kinsale ( ; ) is a historic port and fishing town in County Cork, Ireland. Located approximately south of Cork City on the southeast coast near the Old Head of Kinsale, it sits at the mouth of the River Bandon, and has a population of 5,281 (a ...

prison, which led to the replacement of the regiment accused of perpetrating the abuses. He also defended Roman Catholics

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

from violent abuse by British soldiers. However, the consequence of this was that Hazlitt himself became the target of abuse, it being reported that people cried out "beware of the black rebel" when he walked down the street.

America, 1783–6

Hazlitt's sympathy with the American cause, and the threats of physical harm which he received in Ireland, led him to emigrate to America in April 1783, sailing on the first ship which departed following the conclusion of theAmerican Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

. The Hazlitt family first lived in Philadelphia, where they were doubly stricken with loss. Harriet died in June at about eighteen months old. Another daughter, Esther, the last of the seven Hazlitt children, was born a few weeks later, only to die in September. Their loss was noted to have deeply affected their father. Hazlitt failed to find a post as a minister in Philadelphia, and Duncan Wu has argued that this influenced the condemnatory tone of Hazlitt's preface to his edited collection of three pamphlets by Joseph Priestley. The collection was issued by Robert Bell, the publisher of Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In th ...

's ''Common Sense

''Common Sense'' is a 47-page pamphlet written by Thomas Paine in 1775–1776 advocating independence from Great Britain to people in the Thirteen Colonies. Writing in clear and persuasive prose, Paine collected various moral and political argu ...

''. Indeed, the publication of Hazlitt's edition of Priestley's writings was motivated by the need to publish a profitable work, which would make up for the losses that ''Common Sense'' incurred. Hazlitt used Bell to distribute unsold copies of a pamphlet that he had published in 1773, which provided him with much-needed income.

When Dickinson College

, mottoeng = Freedom is made safe through character and learning

, established =

, type = Private liberal arts college

, endowment = $645.5 million (2022)

, president = J ...

was founded in 1783, Hazlitt had the opportunity to become its first principal, in addition to being appointed to a living at Carlisle

Carlisle ( , ; from xcb, Caer Luel) is a city that lies within the Northern England, Northern English county of Cumbria, south of the Anglo-Scottish border, Scottish border at the confluence of the rivers River Eden, Cumbria, Eden, River C ...

which brought 400 guineas

The guinea (; commonly abbreviated gn., or gns. in plural) was a coin, minted in United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, Great Britain between 1663 and 1814, that contained approximately one-quarter of an ounce of gold. The name came from t ...

a year.Grayling 2000, pp. 351–2. However, the congregation of Carlisle demanded that Hazlitt sign a confession of faith as a condition of his appointment – Hazlitt refused, thereby rejecting the greatest opportunity for personal enrichment that he would have in his entire life, stating (according to his daughter, Margaret) that "he would sooner die in a ditch than submit to human authority in matters of faith". During this time Hazlitt delivered lectures on the evidences of Christianity at the University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (also known as Penn or UPenn) is a private research university in Philadelphia. It is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and is ranked among the highest-regarded universitie ...

, and published popular sermons and tracts, in addition to writing for several local periodicals.Burley 2009, p. 260.

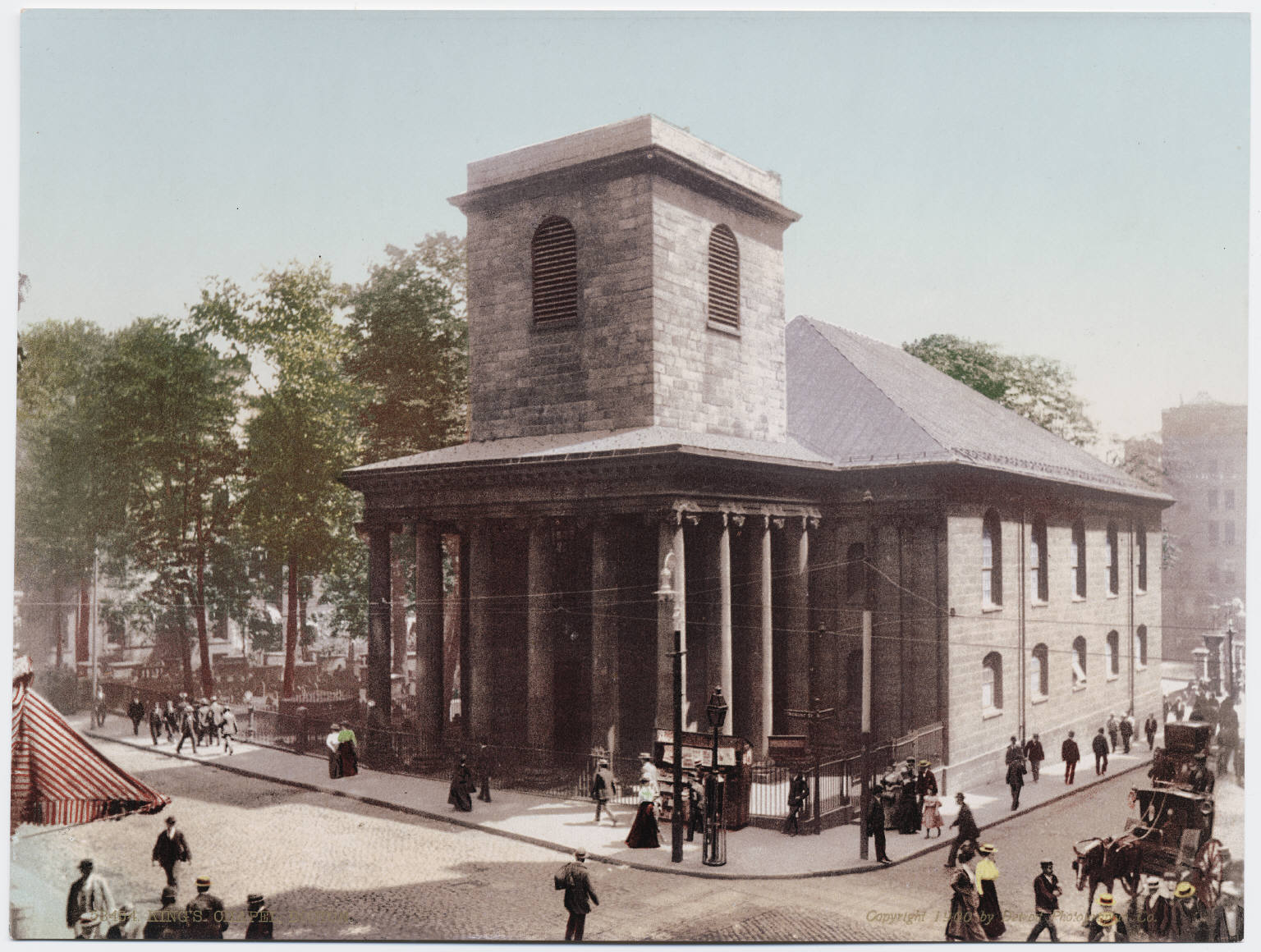

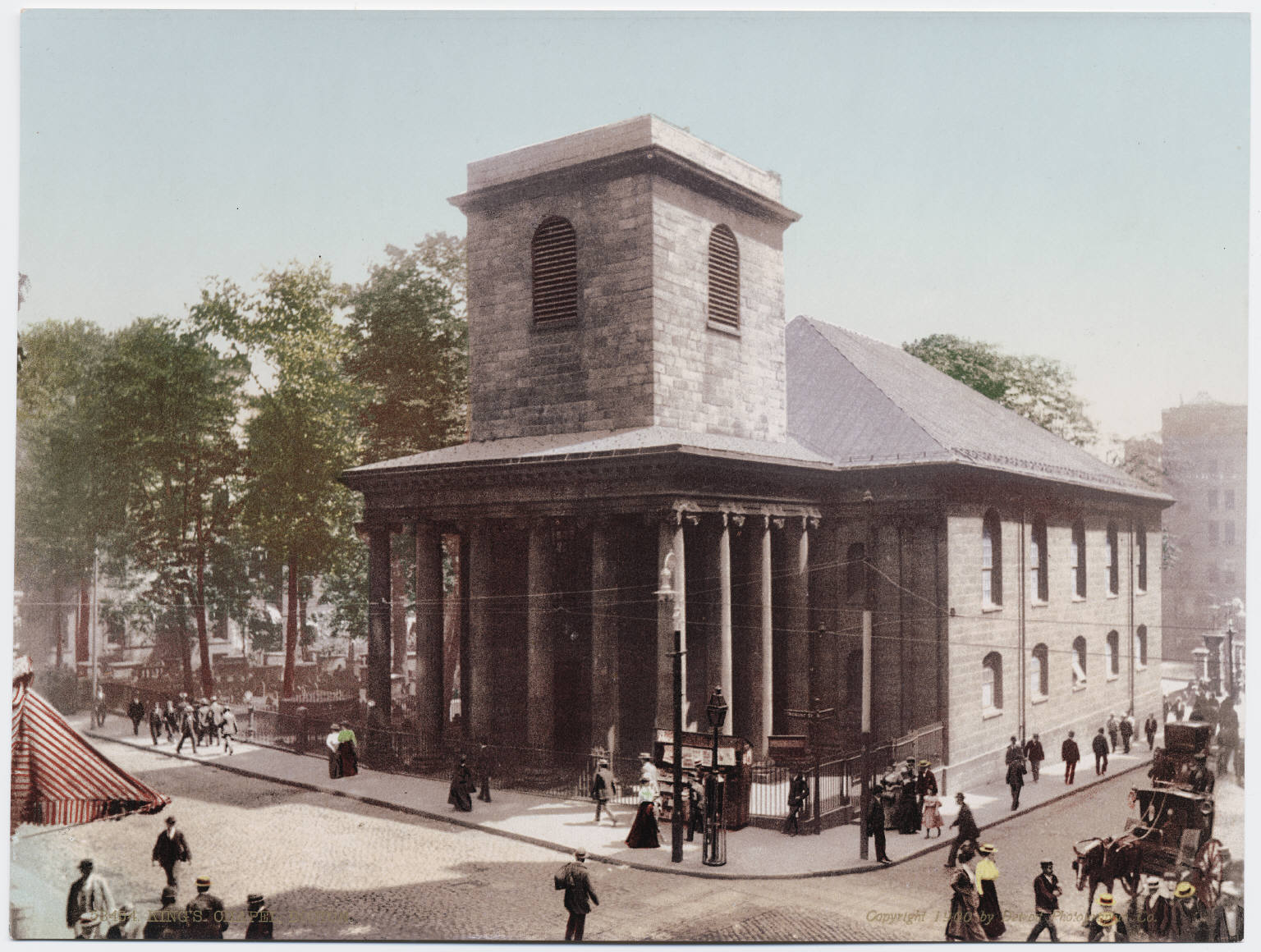

Hazlitt had an important influence on James Freeman's conversion of the

Hazlitt had an important influence on James Freeman's conversion of the King's Chapel

King's Chapel is an American independent christianity, Christian unitarianism, unitarian congregation affiliated with the Unitarian Universalist Association that is "unitarian Christian in theology, anglicanism, Anglican in worship, and congrega ...

in Boston into America's first Unitarian congregation. When Hazlitt arrived in Boston, Freeman was embroiled in a controversy arising from his Arian

Arianism ( grc-x-koine, Ἀρειανισμός, ) is a Christological doctrine first attributed to Arius (), a Christian presbyter from Alexandria, Egypt. Arian theology holds that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, who was begotten by God t ...

beliefs, which—like Hazlitt's own Unitarian doctrines—meant that he held unorthodox views about the Holy Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God the F ...

.Wu 2006, p. 227. This meant that he was denied ordination

Ordination is the process by which individuals are Consecration, consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorization, authorized (usually by the religious denomination, denominational ...

by Samuel Seabury

Samuel Seabury (November 30, 1729February 25, 1796) was the first American Episcopal bishop, the second Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church in the United States of America, and the first Bishop of Connecticut. He was a leading Loyalist ...

, bishop of the Episcopal Church. However, the congregation of the King's Chapel was supportive of Freeman, and Hazlitt encouraged them—both in print, and from the King's Street pulpit—to ignore the bishop and accept Freeman as their pastor. This was a controversial view, since the notion of "lay ordination" was inimical to episcopalianism. On 19 June 1785, the King's Chapel changed its liturgy, removing references to the Trinity and adopting a new prayer book; in November 1787 it ended its affiliation with the Episcopal Church altogether.

Hazlitt also criticised Roman Catholic, Anglican and Episcopalian practices in his writings. He questioned the Biblical basis for praising the Holy Spirit

In Judaism, the Holy Spirit is the divine force, quality, and influence of God over the Universe or over his creatures. In Nicene Christianity, the Holy Spirit or Holy Ghost is the third person of the Trinity. In Islam, the Holy Spirit acts as ...

, and disputed the value of the Thirty-Nine Articles

The Thirty-nine Articles of Religion (commonly abbreviated as the Thirty-nine Articles or the XXXIX Articles) are the historically defining statements of doctrines and practices of the Church of England with respect to the controversies of the ...

of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

, as he had done in his writings from the previous decade.

Minister at Wem

Despite achieving some success as a writer, Hazlitt was unable to secure a permanent post, and in 1786 he returned to England. After failing to obtain a steady income in London, Hazlitt settled with his family at

Despite achieving some success as a writer, Hazlitt was unable to secure a permanent post, and in 1786 he returned to England. After failing to obtain a steady income in London, Hazlitt settled with his family at Wem

Wem may refer to:

* HMS ''Wem'' (1919), a minesweeper of the Royal Navy during World War I

*Weem, a village in Perthshire, Scotland

* Wem, a small town in Shropshire, England

*Wem (musician), hip hop musician

WEM may stand for:

* County Westmeath, ...

in Shropshire. Hazlitt ministered at a dissenting meeting house

A meeting house (meetinghouse, meeting-house) is a building where religious and sometimes public meetings take place.

Terminology

Nonconformist Protestant denominations distinguish between a

* church, which is a body of people who believe in Chr ...

in the town, for which he received a meagre annual stipend

A stipend is a regular fixed sum of money paid for services or to defray expenses, such as for scholarship, internship, or apprenticeship. It is often distinct from an income or a salary because it does not necessarily represent payment for work pe ...

of £30, and ran the local school. He devoted much attention to the education of his son, William, with the intention that he would also become a Unitarian minister. While the Reverend William Hazlitt's intensive tutoring of his son may explain in part the brilliance of the latter's subsequent writings, it was also responsible for his physical and mental breakdown under the strain of his father's expectations. When the younger Hazlitt left the New College at Hackney

The New College at Hackney (more ambiguously known as Hackney College) was a dissenting academy set up in Hackney in April 1786 by the social and political reformer Richard Price and others; Hackney at that time was a village on the outskirts of ...

after only two years, thereby signalling that he would never follow his father into the Unitarian ministry, the latter was bitterly disappointed. In 1798, Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (; 21 October 177225 July 1834) was an English poet, literary critic, philosopher, and theologian who, with his friend William Wordsworth, was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lake Poe ...

visited Hazlitt at Wem – an encounter which was later described by Hazlitt's son in the essay "My First Acquaintance with Poets". In the essay, Hazlitt's life at Wem is described as follows:

While Hazlitt's failure to secure a powerful position in the Unitarian ministry may have been a source of disappointment for him, he continued to participate in Unitarian debate on a national level. In addition to producing three volumes of sermons while living at Wem, he was a regular contributor to periodicals such as the ''Protestant Dissenter's Magazine'' and the ''Universal Theological Magazine''.

In 1801 (possibly early 1802), Hazlitt's son William returned to Wem to paint his portrait. Sitting in the chapel at Wem, with the winter sun raking across the subject's face, the painter described his 64-year-old father as "then in a green old age, with strong-marked features, and scarred with the smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

", who read an old copy of Shaftesbury

Shaftesbury () is a town and civil parish in Dorset, England. It is situated on the A30 road, west of Salisbury, near the border with Wiltshire. It is the only significant hilltop settlement in Dorset, being built about above sea level on a ...

's '' Characteristics'' as he sat. The painting – now in Maidstone Museum and Art Gallery – was shown at the prestigious Royal Academy summer exhibition

The Summer Exhibition is an open art exhibition held annually by the Royal Academy in Burlington House, Piccadilly in central London, England, during the months of June, July, and August. The exhibition includes paintings, prints, drawings, sc ...

in 1802. Paulin has argued that the younger Hazlitt's reference to Shaftesbury is significant, because it establishes "a deliberate connection between advanced Whig culture and his father in the tiny Unitarian meeting-house in Wem".Paulin 1998, p. 5.

In his retirement, Hazlitt lived at Addlestone

Addlestone ( or ) is a town in Surrey, England. It is located approximately southwest of London. The town is the administrative centre of the Borough of Runnymede, of which it is the largest settlement.

History

The town is recorded as ''Attels ...

in Surrey, at Bath

Bath may refer to:

* Bathing, immersion in a fluid

** Bathtub, a large open container for water, in which a person may wash their body

** Public bathing, a public place where people bathe

* Thermae, ancient Roman public bathing facilities

Plac ...

in Somerset, and at Crediton

Crediton is a town and civil parish in the Mid Devon district of Devon in England. It stands on the A377 Exeter to Barnstaple road at the junction with the A3072 road to Tiverton, about north west of Exeter and around from the M5 motorway ...

in Devon, where he died in 1820.

Notes

References

* * Burley, Stephen (2010). "'In this Intolerance I Glory': William Hazlitt (1737–1820) and the Dissenting Periodical", ''The Hazlitt Review'' (3), 9–24. * * * * * * Wu, Duncan (2000). "'Polemical divinity': William Hazlitt at the University of Glasgow", ''Romanticism'' (6), 163–77. * * * Wu, Duncan (2007). "Hazlitt, William (1737–1820)", ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Presaccessed 25 Nov 2011

*

Further reading

* Burley, Stephen (2011). "Hazlitt the Dissenter: Religion, Philosophy, and Politics, 1766–1816", Ph.D. thesis (Queen Mary, University of London

, mottoeng = With united powers

, established = 1785 – The London Hospital Medical College1843 – St Bartholomew's Hospital Medical College1882 – Westfield College1887 – East London College/Queen Mary College

, type = Public researc ...

).

External links

* Burley, StephenA Bibliography of the Writings of William Hazlitt (1737–1820)

(PDF)

Obituary in the Monthly Repository

(1820) {{DEFAULTSORT:Hazlitt, William 1737 births 1820 deaths People from County Tipperary 18th-century Unitarian clergy Irish Unitarians William Hazlitt Alumni of the University of Glasgow Irish non-subscribing Presbyterian ministers