William Golding (other) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir William Gerald Golding (19 September 1911 – 19 June 1993) was a British novelist, playwright, and poet. Best known for his debut novel '' Lord of the Flies'' (1954), he published another twelve volumes of fiction in his lifetime. In 1980, he was awarded the

. William Golding.co.uk. Retrieved 17 June 2012 He was a fellow of the

Son of Alec Golding, a science master at Marlborough Grammar School (1905 to retirement), and Mildred, née Curnoe, William Golding was born at his maternal grandmother's house, 47 Mount Wise,

Son of Alec Golding, a science master at Marlborough Grammar School (1905 to retirement), and Mildred, née Curnoe, William Golding was born at his maternal grandmother's house, 47 Mount Wise,

accessed 13 November 2007

/ref> The house was known as ''Karenza'', the Cornish word for ''love'', and he spent many childhood holidays there. The Golding family lived at 29, The Green,

In ''William Golding: A Critical Study'' (2008), George states that, “Golding experienced two things that he counts the greatest influences on his writing—first, the war and his service in the navy and second, his learning ancient Greek.” Whilst still a teacher at

In ''William Golding: A Critical Study'' (2008), George states that, “Golding experienced two things that he counts the greatest influences on his writing—first, the war and his service in the navy and second, his learning ancient Greek.” Whilst still a teacher at

accessed 16 May 2013

/ref> His publishing success made it possible for Golding to resign his teaching post at Bishop Wordsworth's School in 1961, and he spent that academic year in the United States as writer-in-residence at Hollins College (now Hollins University), near Roanoke, Virginia. Golding won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for '' Darkness Visible'' in 1979, and the

BBC television interview from 1959

*

Interview

by Mary Lynn Scott – Universal Pessimist, Cosmic Optimist

William Golding Ltd

Official Website.

by

Official Facebook page

"William Golding's crisis"

*

William Golding

at University of Exeter Special Collections {{DEFAULTSORT:Golding, William 1911 births 1993 deaths 20th-century British dramatists and playwrights 20th-century English novelists 20th-century English poets Alumni of Brasenose College, Oxford Booker Prize winners British Nobel laureates Commanders of the Order of the British Empire English dramatists and playwrights English historical novelists English Nobel laureates Fellows of the Royal Society of Literature James Tait Black Memorial Prize recipients Knights Bachelor Nobel laureates in Literature People educated at Marlborough Royal Free Grammar School People from Marlborough, Wiltshire People from Newquay Royal Navy officers Royal Navy personnel of World War II Royal Navy sailors Schoolteachers from Wiltshire Writers from Cornwall Writers of fiction set in prehistoric times Writers of historical fiction set in the Middle Ages Military personnel from Cornwall Burials in Wiltshire

Booker Prize

The Booker Prize, formerly known as the Booker Prize for Fiction (1969–2001) and the Man Booker Prize (2002–2019), is a Literary award, literary prize awarded each year for the best novel written in English and published in the United King ...

for '' Rites of Passage'', the first novel in what became his sea trilogy, ''To the Ends of the Earth

''To the Ends of the Earth'' is the title given to a trilogy of nautical, relational novels—''Rites of Passage'' (1980), ''Close Quarters'' (1987), and ''Fire Down Below'' (1989)—by British author William Golding. Set on a former British ...

''. He was awarded the 1983 Nobel Prize in Literature

The 1983 Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded to the British author William Golding "for his novels which, with the perspicuity of realistic narrative art and the diversity and universality of myth, illuminate the human condition in the world of t ...

.

As a result of his contributions to literature, Golding was knighted

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the Christian denomination, church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood ...

in 1988.William Golding: Awards. William Golding.co.uk. Retrieved 17 June 2012 He was a fellow of the

Royal Society of Literature

The Royal Society of Literature (RSL) is a learned society founded in 1820, by George IV of the United Kingdom, King George IV, to "reward literary merit and excite literary talent". A charity that represents the voice of literature in the UK, th ...

. In 2008, ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'' ranked Golding third on its list of "The 50 greatest British writers

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

since 1945".

Biography

Early life

Son of Alec Golding, a science master at Marlborough Grammar School (1905 to retirement), and Mildred, née Curnoe, William Golding was born at his maternal grandmother's house, 47 Mount Wise,

Son of Alec Golding, a science master at Marlborough Grammar School (1905 to retirement), and Mildred, née Curnoe, William Golding was born at his maternal grandmother's house, 47 Mount Wise, Newquay

Newquay ( ; kw, Tewynblustri) is a town on the north coast in Cornwall, in the south west of England. It is a civil parish, seaside resort, regional centre for aerospace industries, spaceport and a fishing port on the North Atlantic coast of ...

, Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a historic county and ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people. Cornwall is bordered to the north and west by the Atlantic ...

.Kevin McCarron, 'Golding, Sir William Gerald (1911–1993)'accessed 13 November 2007

/ref> The house was known as ''Karenza'', the Cornish word for ''love'', and he spent many childhood holidays there. The Golding family lived at 29, The Green,

Marlborough, Wiltshire

Marlborough ( , ) is a market town and Civil parishes in England, civil parish in the England, English Counties of England, county of Wiltshire on the A4 road (England), Old Bath Road, the old main road from London to Bath, Somerset, Bath. Th ...

, Golding and his elder brother Joseph attending the school at which their father taught. Golding's mother was a campaigner for female suffrage; she was Cornish and was considered by her son "a superstitious Celt

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient ...

", who used to tell him old Cornish ghost stories from her own childhood. In 1930, Golding went to Brasenose College, Oxford

Brasenose College (BNC) is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. It began as Brasenose Hall in the 13th century, before being founded as a college in 1509. The library and chapel were added in the mi ...

, where he read Natural Sciences

Natural science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer review and repeatab ...

for two years before transferring to English for his final two years. His original tutor

TUTOR, also known as PLATO Author Language, is a programming language developed for use on the PLATO system at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign beginning in roughly 1965. TUTOR was initially designed by Paul Tenczar for use in co ...

was the chemist Thomas Taylor Thomas Taylor may refer to:

Military

*Thomas H. Taylor (1825–1901), Confederate States Army colonel

*Thomas Happer Taylor (1934–2017), U.S. Army officer; military historian and author; triathlete

*Thomas Taylor (Medal of Honor) (born 1834), Am ...

. In a private journal and in a memoir for his wife he admitted having tried to rape a teenage girl (with whom he had previously taken piano lessons) during a vacation, having apparently misinterpreted what he had perceived as her having "wanted heavy sex".

Golding took his B.A. degree with Second Class Honours in the summer of 1934, and later that year a book of his ''Poems

Poetry (derived from the Greek ''poiesis'', "making"), also called verse, is a form of literature that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language − such as phonaesthetics, sound symbolism, and metre − to evoke meanings in a ...

'' was published by Macmillan & Co

Macmillan Publishers (occasionally known as the Macmillan Group; formally Macmillan Publishers Ltd and Macmillan Publishing Group, LLC) is a British publishing company traditionally considered to be one of the 'Big Five' English language publi ...

, with the help of his Oxford friend, the anthroposophist Adam Bittleston.

In 1935, he took a job teaching English at Michael Hall School

Michael Hall is an independent Steiner Waldorf school in Kidbrooke Park on the edge of Ashdown Forest in East Sussex. Founded in 1925, it is the oldest Steiner school in Britain, it has an enrolment of 400 students aged between three (Kindergar ...

, a Steiner-Waldorf

Waldorf education, also known as Steiner education, is based on the educational philosophy of Rudolf Steiner, the founder of anthroposophy. Its educational style is holistic, intended to develop pupils' intellectual, artistic, and practical skil ...

school then in

Streatham, South London, staying there for two years. After a year in Oxford studying for a Diploma of Education, he was a schoolmaster teaching English and music at Maidstone Grammar School

Maidstone Grammar School (MGS) is a grammar school in Maidstone, England. The school was founded in 1549 after Protector Somerset sold Corpus Christi Hall on behalf of King Edward VI to the people of Maidstone for £200. The Royal Charter for ...

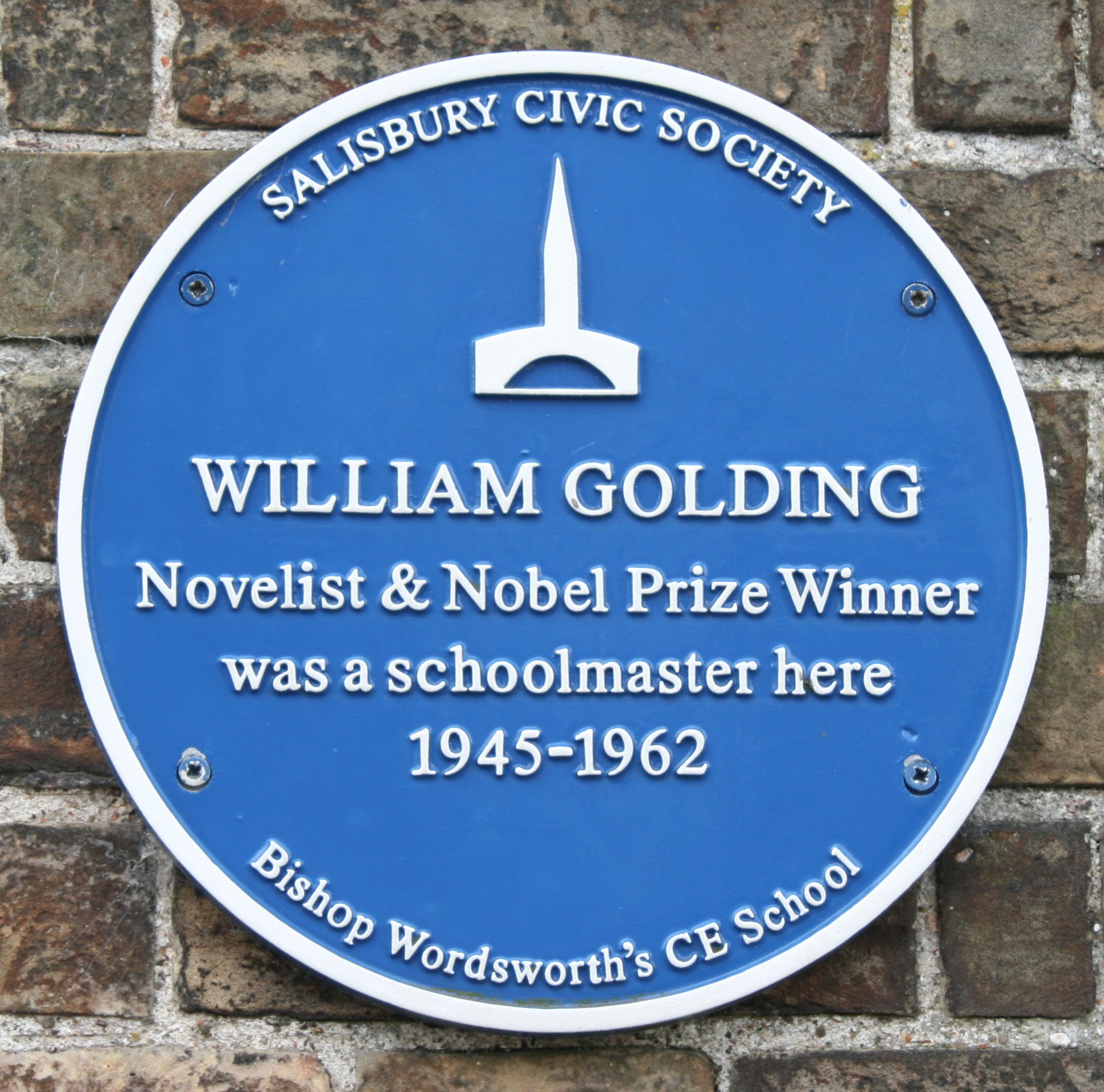

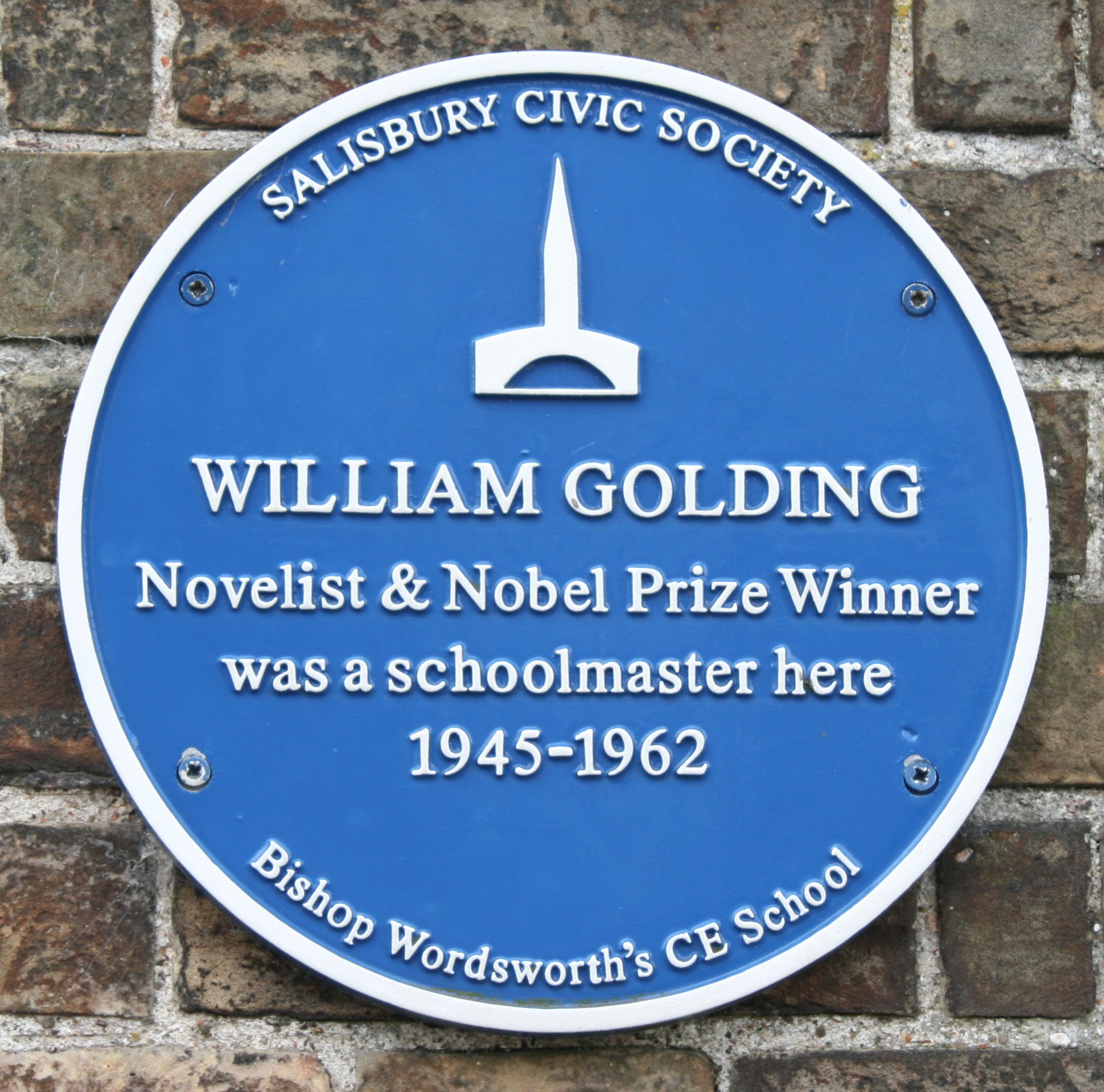

1938 – 1940, before moving to Bishop Wordsworth's School

Bishop Wordsworth's School is a Church of England boys' grammar school in Salisbury, Wiltshire for boys aged 11 to 18. The school is regularly amongst the top-performing schools in England, and in 2010 was the school with the best results in the ...

, Salisbury

Salisbury ( ) is a cathedral city in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers Avon, Nadder and Bourne. The city is approximately from Southampton and from Bath.

Salisbury is in the southeast of Wil ...

, in April 1940. There he taught English, Philosophy, Greek, and drama until joining the navy on 18 December 1940, reporting for duty at HMS Raleigh

Six ships and one shore establishment of the Royal Navy have borne the name HMS ''Raleigh'', after Sir Walter Raleigh:

* HMS ''Raleigh'' was a 32-gun fifth rate, previously the American . She was captured in 1778 by and and was commissioned int ...

. He returned in 1945 and taught the same subjects until 1961.

Golding kept a personal journal for over 22 years William Golding Website, https://william-golding.co.uk/timeline, Accessed 28 November 2020. from 1971 until the night before his death, it contained approximately 2.4 million words in total. The journal was initially used by Golding in order to record his dreams, but over time it began to function as a record of his life. The journals contained insights including retrospective thoughts about his novels and memories from his past. At one point Golding described setting his students up into two groups to fight each other – an experience he drew on when writing ''Lord of the Flies''. John Carey, the emeritus professor of English literature at Oxford University, was eventually given 'unprecedented access to Golding's unpublished papers and journals by the Golding estate'. Though Golding had not written the journals specifically so that a biography could be written about him, Carey published ''William Golding: The Man Who Wrote Lord of the Flies'' in 2009.

Marriage and family

Golding was engaged to Molly Evans, a woman from Marlborough, who was well liked by both of his parents. However, he broke off the engagement and married Ann Brookfield, an analytical chemist, on 30 September 1939. They had two children, David (born September 1940) and Judith (born July 1945).War service

DuringWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, Golding joined the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

in 1940. He served on a destroyer which was briefly involved in the pursuit and sinking of the German battleship ''Bismarck''. Golding participated in the invasion of Normandy on D-Day, commanding a landing craft

Landing craft are small and medium seagoing watercraft, such as boats and barges, used to convey a landing force (infantry and vehicles) from the sea to the shore during an amphibious assault. The term excludes landing ships, which are larger. Pr ...

that fired salvoes of rockets onto the beaches. He was also in action at Walcheren in October and November 1944, during which time 10 out of 27 assault craft that went into the attack were sunk. Golding rose to the rank of lieutenant.

"Crisis"

Golding had a troubled relationship with alcohol; Judy Carver notes that her father was "always very open, if rueful, about problems with drink". Golding suggested that his self-described "crisis", of which alcoholism played a major part, had plagued him his entire life.Kendall p. 466 John Carey mentions several instances ofbinge drinking

Binge drinking, or heavy episodic drinking, is drinking alcoholic beverages with an intention of becoming intoxicated by heavy consumption of alcohol over a short period of time, but definitions ( see below) vary considerably.

Binge drinking ...

in his biography, including Golding's experiences in 1963; whilst on holiday in Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

(when he was meant to have been finishing his novel ''The Spire

''The Spire'' is a 1964 novel by English author William Golding. "A dark and powerful portrait of one man's will", it deals with the construction of a 404-foot-high spire loosely based on Salisbury Cathedral,Paul, Leslie. "The Spire That Stay ...

''), after working on his writing in the morning, he would go to his preferred " Kapheneion" to drink at midday.Carey p. 277 By the evening he would move onto ouzo and brandy

Brandy is a liquor produced by distilling wine. Brandy generally contains 35–60% alcohol by volume (70–120 US proof) and is typically consumed as an after-dinner digestif. Some brandies are aged in wooden casks. Others are coloured with ...

; he developed a reputation locally for "provoking explosions".

Unfortunately, the eventual publication of ''The Spire'' the following year did not help Golding's developing struggle with alcohol; it had precisely the opposite effect, with the novel's scathingly negative reviews in a BBC radio broadcast affecting him severely. Following the publication of '' The Pyramid'' in 1967, Golding experienced a severe writer's block

Writer's block is a condition, primarily associated with writing, in which an author is either unable to produce new work or experiences a creative slowdown. Mike Rose found that this creative stall is not a result of commitment problems or th ...

: the result of myriad crises (family anxieties, insomnia

Insomnia, also known as sleeplessness, is a sleep disorder in which people have trouble sleeping. They may have difficulty falling asleep, or staying asleep as long as desired. Insomnia is typically followed by daytime sleepiness, low energy, ...

, and a general sense of dejection). Golding eventually became unable to deal with what he perceived to be the intense reality of his life without first drinking copious amounts of alcohol. Tim Kendall

Tim Kendall (born 1970) is an English poet, editor and critic. He was born in Plymouth. In 1994 he co-founded the magazine ''Thumbscrew'', which published work by poets including Ted Hughes, Seamus Heaney and Miroslav Holub, and which ran under h ...

suggests that these experiences manifest in Golding's writing as the character Wilf in ''The Paper Men

''The Paper Men'' is a 1984 novel by British writer William Golding.

Plot Summary

The protagonist in the novel is Wilfred Barclay, a curmudgeonly writer who has a drinking problem, a dead marriage, and the incurable itches of middle-aged lust ...

''; "an ageing novelist whose alcohol-sodden journeys across Europe are bankrolled by the continuing success of his first book".

By the late 1960s, Golding was relying on alcohol – which he referred to as "the old, old anodyne". His first steps towards recovery came from his study of Carl Jung

Carl Gustav Jung ( ; ; 26 July 1875 – 6 June 1961) was a Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst who founded analytical psychology. Jung's work has been influential in the fields of psychiatry, anthropology, archaeology, literature, philo ...

's writings, and in what he called "an admission of discipleship". He travelled to Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

in 1971 to see Jung's landscapes for himself.Kendall, Tim. ''Update.'' Email, ''University of Exeter'', 4 June 2021. That same year, he started keeping a journal in which he recorded and interpreted his dreams; the last entry is from the day before he died, in 1993, and the volumes-long work came to be thousands of pages long by this time.

The crisis did inevitably affect Golding's output, and his next novel, '' Darkness Visible'', would be published twelve years after ''The Pyramid''; a far cry from the prolific author who had produced six novels in thirteen years since the start of his career. Despite this, the extent of Golding's recovery is evident from the fact that this was only the first of six further novels that Golding completed before his death.

Death

In 1985, Golding and his wife moved to a house called Tullimaar inPerranarworthal

Perranarworthal ( kw, Peran ar Wodhel) is a civil parish and village in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. The village is about four miles (6.5 km) northwest of Falmouth and five miles (8 km) southwest of Truro. Perranarworthal p ...

, near Truro, Cornwall. He died of heart failure eight years later on 19 June 1993. His body was buried in the parish churchyard of Bowerchalke

Bowerchalke is a village and civil parish in Wiltshire, England, about southwest of Salisbury. It is in the south of the county, about from the boundary with Dorset and from that with Hampshire. The parish includes the hamlets of Mead End, Mi ...

near his former home and the Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershire ...

county border with Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial county, ceremonial and non-metropolitan county, non-metropolitan counties of England, county in western South East England on the coast of the English Channel. Home to two major English citi ...

and Dorset

Dorset ( ; archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a county in South West England on the English Channel coast. The ceremonial county comprises the unitary authority areas of Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole and Dorset (unitary authority), Dors ...

.

On his death he left the draft of a novel, '' The Double Tongue'', set in ancient Delphi, which was published posthumously in 1995.

Career

Writing success

In ''William Golding: A Critical Study'' (2008), George states that, “Golding experienced two things that he counts the greatest influences on his writing—first, the war and his service in the navy and second, his learning ancient Greek.” Whilst still a teacher at

In ''William Golding: A Critical Study'' (2008), George states that, “Golding experienced two things that he counts the greatest influences on his writing—first, the war and his service in the navy and second, his learning ancient Greek.” Whilst still a teacher at Bishop Wordsworth's School

Bishop Wordsworth's School is a Church of England boys' grammar school in Salisbury, Wiltshire for boys aged 11 to 18. The school is regularly amongst the top-performing schools in England, and in 2010 was the school with the best results in the ...

, in 1951 Golding began writing a manuscript of the novel initially titled ''Strangers from Within''.

In September 1953, after rejections from seven other publishers, Golding sent a manuscript to Faber and Faber

Faber and Faber Limited, usually abbreviated to Faber, is an independent publishing house in London. Published authors and poets include T. S. Eliot (an early Faber editor and director), W. H. Auden, Margaret Storey, William Golding, Samuel B ...

and was initially rejected by their reader, Jan Perkins, who labelled it as "Rubbish & dull. Pointless". His book, however, was championed by Charles Monteith, a new editor at the firm. Monteith asked for some changes to the text and the novel was published in September 1954 as '' Lord of the Flies''.

After moving in 1958 from Salisbury

Salisbury ( ) is a cathedral city in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers Avon, Nadder and Bourne. The city is approximately from Southampton and from Bath.

Salisbury is in the southeast of Wil ...

to nearby Bowerchalke

Bowerchalke is a village and civil parish in Wiltshire, England, about southwest of Salisbury. It is in the south of the county, about from the boundary with Dorset and from that with Hampshire. The parish includes the hamlets of Mead End, Mi ...

, he met his fellow villager and walking companion James Lovelock

James Ephraim Lovelock (26 July 1919 – 26 July 2022) was an English independent scientist, environmentalist and futurist. He is best known for proposing the Gaia hypothesis, which postulates that the Earth functions as a self-regulating sys ...

. The two discussed Lovelock's hypothesis

A hypothesis (plural hypotheses) is a proposed explanation for a phenomenon. For a hypothesis to be a scientific hypothesis, the scientific method requires that one can test it. Scientists generally base scientific hypotheses on previous obse ...

, that the living matter of the planet Earth functions like a single organism, and Golding suggested naming this hypothesis after Gaia

In Greek mythology, Gaia (; from Ancient Greek , a poetical form of , 'land' or 'earth'),, , . also spelled Gaea , is the personification of the Earth and one of the Greek primordial deities. Gaia is the ancestral mother—sometimes parthenog ...

, the personification of the Earth in Greek mythology, and mother of the Titans.James Lovelock, 'What is Gaia?'accessed 16 May 2013

/ref> His publishing success made it possible for Golding to resign his teaching post at Bishop Wordsworth's School in 1961, and he spent that academic year in the United States as writer-in-residence at Hollins College (now Hollins University), near Roanoke, Virginia. Golding won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for '' Darkness Visible'' in 1979, and the

Booker Prize

The Booker Prize, formerly known as the Booker Prize for Fiction (1969–2001) and the Man Booker Prize (2002–2019), is a Literary award, literary prize awarded each year for the best novel written in English and published in the United King ...

for '' Rites of Passage'' in 1980. In 1983, he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, caption =

, awarded_for = Outstanding contributions in literature

, presenter = Swedish Academy

, holder = Annie Ernaux (2022)

, location = Stockholm, Sweden

, year = 1901

, ...

, and was according to the ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

'' "an unexpected and even contentious choice".

Having been appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established o ...

(CBE) in the 1966 New Year Honours

The New Year Honours 1966 were appointments in many of the Commonwealth realms of Queen Elizabeth II to various orders and honours to reward and highlight good works by citizens of those countries. They were announced in supplements to the ''Lond ...

, Golding was appointed a Knight Bachelor

The title of Knight Bachelor is the basic rank granted to a man who has been knighted by the monarch but not inducted as a member of one of the organised orders of chivalry; it is a part of the British honours system. Knights Bachelor are the ...

in the 1988 Birthday Honours

Queen's Birthday Honours are announced on or around the date of the Queen's Official Birthday in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United Kingdom. The dates vary, both from year to year and from country to country. All are published in supple ...

. In September 1993, only a few months after his unexpected death, the First International William Golding Conference was held in France.

Fiction

His first novel, '' Lord of the Flies'' (1954; film, 1963 and 1990; play, adapted by Nigel Williams, 1995), describes a group of boys stranded on a tropical island descending into a lawless and increasingly wild existence before being rescued. '' The Inheritors'' (1955) depicts a tribe of gentle Neanderthals encountering modern humans, who by comparison are deceitful and violent. His 1956 novel ''Pincher Martin

''Pincher Martin'' (published in America as ''Pincher Martin: The Two Deaths of Christopher Martin'') is a novel by British people, British writer William Golding, first published in 1956. It is Golding's third novel, following ''The Inheritors ( ...

'' records the thoughts of a drowning sailor. '' Free Fall'' (1959) explores the question of freedom of choice. The novel's narrator, a World War Two soldier in a German POW Camp, endures interrogation and solitary confinement. After these events and while recollecting the experiences, he looks back over the choices he has made, trying to trace precisely where he lost the freedom to make his own decisions. ''The Spire

''The Spire'' is a 1964 novel by English author William Golding. "A dark and powerful portrait of one man's will", it deals with the construction of a 404-foot-high spire loosely based on Salisbury Cathedral,Paul, Leslie. "The Spire That Stay ...

'' (1964) follows the construction (and near collapse) of an impossibly large spire on the top of a medieval cathedral (generally assumed to be Salisbury Cathedral

Salisbury Cathedral, formally the Cathedral Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary, is an Anglican cathedral in Salisbury, England. The cathedral is the mother church of the Diocese of Salisbury and is the seat of the Bishop of Salisbury.

The buildi ...

).

Golding's 1967 novel, '' The Pyramid'', consists of three linked stories with a shared setting in a small English town based partly on Marlborough where Golding grew up. ''The Scorpion God

''The Scorpion God'' is a collection of three novellas by William Golding published in 1971. They are all set in the distant past: "The Scorpion God" in Ancient Egypt, "Clonk Clonk" in pre-historic Africa, and "Envoy Extraordinary" in Ancient Rom ...

'' (1971) contains three novellas, the first set in an ancient Egyptian court ("The Scorpion God"); the second describing a prehistoric African hunter-gatherer group ("Clonk, Clonk"); and the third in the court of a Roman emperor ("Envoy Extraordinary"). The last of these, originally published in 1956, was reworked by Golding into a play, ''The Brass Butterfly'', in 1958. From 1971 to 1979, Golding published no novels. After this period he published '' Darkness Visible'' (1979): a story involving terrorism, paedophilia, and a mysterious figure who survives a fire in the Blitz

The Blitz was a German bombing campaign against the United Kingdom in 1940 and 1941, during the Second World War. The term was first used by the British press and originated from the term , the German word meaning 'lightning war'.

The Germa ...

and appears to have supernatural powers. In 1980, Golding published '' Rites of Passage'', the first of his novels about a voyage to Australia in the early nineteenth century. The novel won the Booker Prize

The Booker Prize, formerly known as the Booker Prize for Fiction (1969–2001) and the Man Booker Prize (2002–2019), is a Literary award, literary prize awarded each year for the best novel written in English and published in the United King ...

in 1980 and Golding followed this success with ''Close Quarters

Overcrowding or crowding is the condition where more people are located within a given space than is considered tolerable from a safety and health perspective. Safety and health perspectives depend on current environments and on Norm (social), lo ...

'' (1987) and '' Fire Down Below'' (1989) to complete his 'sea trilogy', later published as one volume entitled ''To the Ends of the Earth

''To the Ends of the Earth'' is the title given to a trilogy of nautical, relational novels—''Rites of Passage'' (1980), ''Close Quarters'' (1987), and ''Fire Down Below'' (1989)—by British author William Golding. Set on a former British ...

''. In 1984, he published ''The Paper Men

''The Paper Men'' is a 1984 novel by British writer William Golding.

Plot Summary

The protagonist in the novel is Wilfred Barclay, a curmudgeonly writer who has a drinking problem, a dead marriage, and the incurable itches of middle-aged lust ...

'': an account of the struggles between a novelist and his would-be biographer.

List of works

Poetry

*''Poems

Poetry (derived from the Greek ''poiesis'', "making"), also called verse, is a form of literature that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language − such as phonaesthetics, sound symbolism, and metre − to evoke meanings in a ...

'' (1934)

Drama

*''The Brass Butterfly

"Envoy Extraordinary" is a 1956 novella by British writer William Golding, first published by Eyre & Spottiswoode as one third of the collection '', Never'', alongside "Consider Her Ways" by John Wyndham and "Boy in Darkness" by Mervyn Peake. It w ...

'' (1958)

Novels

*'' Lord of the Flies'' (1954) *'' The Inheritors'' (1955) *''Pincher Martin

''Pincher Martin'' (published in America as ''Pincher Martin: The Two Deaths of Christopher Martin'') is a novel by British people, British writer William Golding, first published in 1956. It is Golding's third novel, following ''The Inheritors ( ...

'' (1956)

*'' Free Fall'' (1959)

*''The Spire

''The Spire'' is a 1964 novel by English author William Golding. "A dark and powerful portrait of one man's will", it deals with the construction of a 404-foot-high spire loosely based on Salisbury Cathedral,Paul, Leslie. "The Spire That Stay ...

'' (1964)

*'' The Pyramid'' (1967)

*'' Darkness Visible'' (1979) ( James Tait Black Memorial Prize)

*''To the Ends of the Earth

''To the Ends of the Earth'' is the title given to a trilogy of nautical, relational novels—''Rites of Passage'' (1980), ''Close Quarters'' (1987), and ''Fire Down Below'' (1989)—by British author William Golding. Set on a former British ...

'' (trilogy)

**'' Rites of Passage'' (1980) (Booker Prize

The Booker Prize, formerly known as the Booker Prize for Fiction (1969–2001) and the Man Booker Prize (2002–2019), is a Literary award, literary prize awarded each year for the best novel written in English and published in the United King ...

)

**''Close Quarters

Overcrowding or crowding is the condition where more people are located within a given space than is considered tolerable from a safety and health perspective. Safety and health perspectives depend on current environments and on Norm (social), lo ...

'' (1987)

**'' Fire Down Below'' (1989)

*''The Paper Men

''The Paper Men'' is a 1984 novel by British writer William Golding.

Plot Summary

The protagonist in the novel is Wilfred Barclay, a curmudgeonly writer who has a drinking problem, a dead marriage, and the incurable itches of middle-aged lust ...

'' (1984)

*'' The Double Tongue'' (posthumous publication 1995)

Collections

*''The Scorpion God

''The Scorpion God'' is a collection of three novellas by William Golding published in 1971. They are all set in the distant past: "The Scorpion God" in Ancient Egypt, "Clonk Clonk" in pre-historic Africa, and "Envoy Extraordinary" in Ancient Rom ...

'' (1971)

**"The Scorpion God"

**"Clonk Clonk"

** "Envoy Extraordinary"

Non-fiction

*''The Hot Gates

''The Hot Gates'' is the title of a collection of essays by William Golding, author of ''Lord of the Flies''. The collection is divided into four sections: "People and Places", "Books", "Westward Look" and "Caught in a Bush". Published in 196 ...

'' (1965)

*''A Moving Target

''A Moving Target'' is a collection of essays and lectures written by William Golding. It was first published in 1982D-Day

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on Tuesday, 6 June 1944 of the Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during World War II. Codenamed Operation Neptune and often referred to as D ...

.

*''Circle Under the Sea'' is an adventure novel about a writer who sails to discover archaeological treasures off the coast of the Scilly Isles.

*''Short Measure'' is a novel set in a British school akin to Bishop Wordsworth's.Carey, p. 142

Audiobooks

* 2005: ''Lord of the Flies'' (read by the author), Listening Library,Citations

General and cited sources

* * *Kendall, Tim. "William Golding's Great Dream." Essays in Criticism, Vol. 68, Issue. 4, October 2018, pp. 466–487. ''Oxford Academic'' (Website), https://academic.oup.com/eic/article-abstract/68/4/466/5126810?redirectedFrom=PDF. Accessed 3 June 2021.Further reading

* Crompton, Donald. ''A View from the Spire: William Golding's Later Novels.'' Basil Blackwell Publisher Ltd, Oxford, 1985. https://archive.org/details/viewfromspirew00crom/page/n5/mode/2up. . * L. L. Dickson. ''The Modern Allegories of William Golding'' (University of South Florida Press, 1990). . * R. A. Gekoski and P. A. Grogan, ''William Golding: A Bibliography'', London, André Deutsch, 1994. . * Golding, Judy. ''The Children of Lovers.'' Faber & Faber, 2012. . * Gregor, Ian and Kinkead-Weekes, Mark. ''William Golding: A critical Study''. 2nd Revised Edition, Faber & Faber, 1984. * McCarron, Kevin. (2007) 'From Psychology to Ontology: William Golding's Later Fiction.' In: MacKay M., Stonebridge L. (eds) British Fiction After Modernism. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230801394_15. * McCarron, Kevin. ''William Golding (Writers and Their Work).'' 2nd Edition, Northcote House Publishers Ltd, 2006. . * "Boys Armed with Sticks: William Golding's Lord of the Flies". Chapter in B. Schoene-Harwood. ''Writing Men''. Edinburgh University Press, 2000. * Tiger, Virginia. ''William Golding: The Dark Fields of Discovery.'' Marion Boyars Publishers Ltd, 1974. . * Tiger, Virginia. ''William Golding: The Unmoved Target.'' Marion Boyars Publishers Ltd, 2003. * Ladenthin, Volker: Golding, Herr der Fliegen; Verne, 2 Jahre Ferien; Schlüter, Level 4 – Stadt der Kinder. In: engagement (1998) H. 4 S. 271–274.External links

BBC television interview from 1959

*

Interview

by Mary Lynn Scott – Universal Pessimist, Cosmic Optimist

William Golding Ltd

Official Website.

by

D. M. Thomas

Donald Michael Thomas (born 27 January 1935), is a British poet, translator, novelist, editor, biographer and playwright. His work has been translated into 30 languages.

Working primarily as a poet throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Thomas's 1981 ...

– Guardian – Saturday 10 June 2006 (''Review'' Section)

Official Facebook page

"William Golding's crisis"

*

William Golding

at University of Exeter Special Collections {{DEFAULTSORT:Golding, William 1911 births 1993 deaths 20th-century British dramatists and playwrights 20th-century English novelists 20th-century English poets Alumni of Brasenose College, Oxford Booker Prize winners British Nobel laureates Commanders of the Order of the British Empire English dramatists and playwrights English historical novelists English Nobel laureates Fellows of the Royal Society of Literature James Tait Black Memorial Prize recipients Knights Bachelor Nobel laureates in Literature People educated at Marlborough Royal Free Grammar School People from Marlborough, Wiltshire People from Newquay Royal Navy officers Royal Navy personnel of World War II Royal Navy sailors Schoolteachers from Wiltshire Writers from Cornwall Writers of fiction set in prehistoric times Writers of historical fiction set in the Middle Ages Military personnel from Cornwall Burials in Wiltshire