William F. Barrett on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

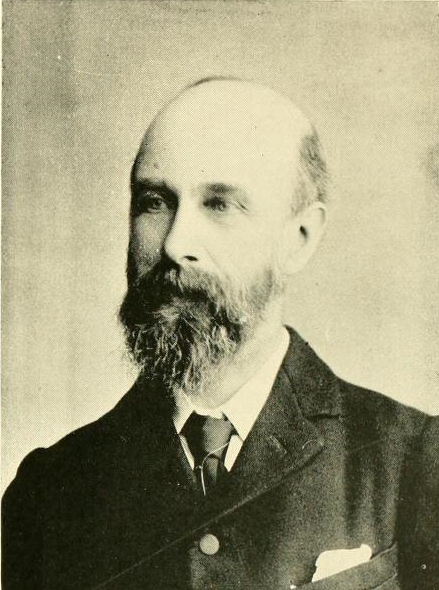

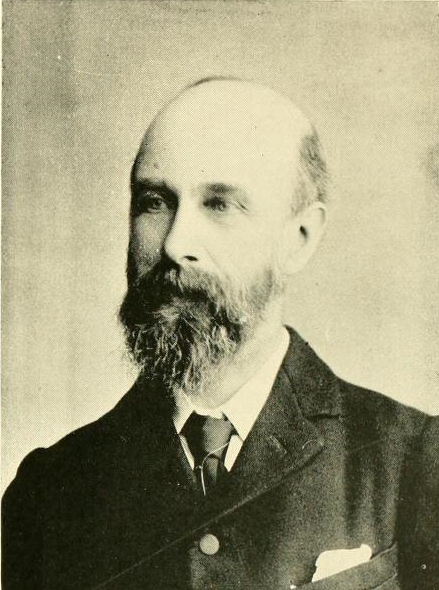

Sir William Fletcher Barrett (10 February 1844 in Kingston, Jamaica – 26 May 1925) was an English

retrieved 2 Feb 2011

Barrett then took chemistry and physics at the

Barrett became interested in the

Barrett became interested in the

''Practical Physics: An Introductory Handbook for the Physical Laboratory.''

(1892) London: Percival & Co.

''On the Threshold of a New World of Thought: An Examination of the Phenomena of Spiritualism''

(1908) London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co.

''Psychical Research.

' (1911) New York: Henry Holt & Co. * ''Swedenborg: The Savant and the Seer.'' (1912) London: Watkins.

''On the Threshold of the Unseen: An Examination of the Phenomena of Spiritualism and of the Evidence for Survival After Death''

(1917) London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co.

Volltext

''The Divining Rod: An Experimental and Psychological Investigation.''

[with

physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate caus ...

and parapsychologist.

Life

He was born in Jamaica where his father,William Garland Barrett

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Eng ...

, who was an amateur naturalist, Congregationalist minister and a member of the London Missionary Society

The London Missionary Society was an interdenominational evangelical missionary society formed in England in 1795 at the instigation of Welsh Congregationalist minister Edward Williams. It was largely Reformed in outlook, with Congregational miss ...

, ran a station for saving African slaves. There he lived with his mother, Martha Barrett, née Fletcher, and a brother and sister. The family returned to their native England in Royston, Hertfordshire in 1848 where another sister, the social reformer Rosa Mary Barrett was born. In 1855 they moved to Manchester and Barrett was then educated at Old Trafford Grammar School. Gauld, Alan. (2004). ''Barrett, Sir William Fletcher (1844–1925)''. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Pressretrieved 2 Feb 2011

Barrett then took chemistry and physics at the

Royal College of Chemistry

The Royal College of Chemistry: the laboratories. Lithograph

The Royal College of Chemistry (RCC) was a college originally based on Oxford Street in central London, England. It operated between 1845 and 1872.

The original building was designed ...

and then became the science master at the London International College (1867–9) before becoming assistant to John Tyndall at the Royal Institution (1863–1866). He then taught at the Royal School of Naval Architecture.

In 1873 he became Professor of Experimental Physics at the Royal College of Science for Ireland

The Royal College of Science for Ireland (RCScI) was an institute for higher education in Dublin which existed from 1867 to 1926, specialising in physical sciences and applied science. It was originally based on St. Stephen's Green, moving in 1 ...

. From the early 1880s he lived with his mother, sister, and two live-in servants in a residence at Kingstown (now Dún Laoghaire

Dún Laoghaire ( , ) is a suburban coastal town in Dublin in Ireland. It is the administrative centre of Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown.

The town was built following the 1816 legislation that allowed the building of a major port to serve Dubli ...

). Barrett discovered Stalloy (see Permalloy), a silicon-iron alloy used in electrical engineering and also did a lot of work on sensitive flames and their uses in acoustic demonstrations. During his studies of metals and their properties, Barrett worked with W. Brown and R. A. Hadfield. He also discovered the shortening of nickel through magnetisation in 1882.

When Barrett developed cataract

A cataract is a cloudy area in the lens of the eye that leads to a decrease in vision. Cataracts often develop slowly and can affect one or both eyes. Symptoms may include faded colors, blurry or double vision, halos around light, trouble w ...

s in his later years, he also began to study biology with a series of experiments designed to locate and successfully analyze causative agents within the eyes. The result of these experiments was a machine called the entoptiscope. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

in June 1899 and was also a fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh

The Royal Society of Edinburgh is Scotland's national academy of science and letters. It is a registered charity that operates on a wholly independent and non-partisan basis and provides public benefit throughout Scotland. It was established i ...

and the Royal Dublin Society. He was knighted in 1912. He married Florence Willey in 1916. He died at home, 31 Devonshire Place in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

.

Barrett's last book, ''Christian Science: An Examination of the Religion of Health'' was completed and published after his death in 1926 by his sister Rosa M. Barrett.

Psychical research

Barrett became interested in the

Barrett became interested in the paranormal

Paranormal events are purported phenomena described in popular culture, folk, and other non-scientific bodies of knowledge, whose existence within these contexts is described as being beyond the scope of normal scientific understanding. Nota ...

in the 1860s after having an experience with mesmerism

Animal magnetism, also known as mesmerism, was a protoscientific theory developed by German doctor Franz Mesmer in the 18th century in relation to what he claimed to be an invisible natural force (''Lebensmagnetismus'') possessed by all liv ...

. Barrett believed that he had been witness to thought transference and by the 1870s he was investigating poltergeists. In September 1876 Barrett published a paper outlining the result of these investigations and by 1881 he had published preliminary accounts of his additional experiments with thought transference in the journal ''Nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physics, physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomenon, phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. ...

''. The publication caused controversy and in the wake of this Barrett decided to found a society of like-minded individuals to help further his research. Barrett held conference between 5–6 January 1882 in London. In February the Society for Psychical Research

The Society for Psychical Research (SPR) is a nonprofit organisation in the United Kingdom. Its stated purpose is to understand events and abilities commonly described as psychic or paranormal. It describes itself as the "first society to condu ...

(SPR) was formed. Oppenheim, Janet. (1985). ''The Other World: Spiritualism and Psychical Research in England, 1850-1914''. Cambridge University Press. pp. 137-372.

Barrett was a Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

and spiritualist

Spiritualism is the metaphysical school of thought opposing physicalism and also is the category of all spiritual beliefs/views (in monism and dualism) from ancient to modern. In the long nineteenth century

The ''long nineteenth century'' i ...

member of the SPR. Although he had founded the society, Barrett was only truly active for a year, and in 1884 founded the American Society for Psychical Research

The American Society for Psychical Research (ASPR) is the oldest psychical research organization in the United States dedicated to parapsychology. It maintains offices and a library, in New York City, which are open to both members and the gener ...

. He became president of the society in 1904 and continued to submit articles to their journal. From 1908–14 Barrett was active in the Dublin Section of the Society for Psychical Research, a group which attracted many important members including Sir John Pentland Mahaffy, T.W. Rolleston, Sir Archibald Geikie, and Lady Augusta Gregory.

In the late 19th century the Creery Sisters

Telepathy () is the purported vicariousness, vicarious transmission of information from one person's mind to another's without using any known human sensory channels or physical interaction. The term was first coined in 1882 by the classical sch ...

(Mary, Alice, Maud, Kathleen, and Emily) were tested by Barrett and other members of the SPR who believed them to have genuine psychic ability, however, the sisters later confessed to fraud by describing their method of signal codes that they had utilized. Barrett and the other members of the SPR such as Edmund Gurney

Edmund Gurney (23 March 184723 June 1888) was an England, English psychologist and parapsychologist. At the time the term for research of paranormal activities was "psychical research".

Early life

Gurney was born at Hersham, near Walton-on-Tham ...

and Frederic W. H. Myers

Frederic William Henry Myers (6 February 1843 – 17 January 1901) was a British poet, classicist, philologist, and a founder of the Society for Psychical Research. Myers' work on psychical research and his ideas about a "subliminal self" w ...

had been easily duped.

As a believer in telepathy

Telepathy () is the purported vicarious transmission of information from one person's mind to another's without using any known human sensory channels or physical interaction. The term was first coined in 1882 by the classical scholar Frederic W ...

, Barrett denounced the muscle reading

Muscle reading, also known as " Hellstromism", "Cumberlandism" or "contact mind reading", is a technique used by mentalists to determine the thoughts or knowledge of a subject, the effect of which tends to be perceived as a form of mind reading. ...

of Stuart Cumberland

Stuart Cumberland (1857–1922) was an English mentalist known for his demonstrations of "thought reading".

Cumberland was famous for performing blindfolded feats such as identifying a hidden object in a room that a person had picked out or ...

and other magicians as "pseudo" thought readers.

Barrett helped to publish Frederick Bligh Bond

Frederick Bligh Bond (30 June 1864 – 8 March 1945), generally known by his second given name ''Bligh'', was an English architect, illustrator, archaeologist and psychical researcher.

Early life

Bligh Bond was the son of the Rev. Frederick ...

's book ''Gate of Remembrance'' (1918) which was based on alleged psychical excavations at Glastonbury Abbey

Glastonbury Abbey was a monastery in Glastonbury, Somerset, England. Its ruins, a grade I listed building and scheduled ancient monument, are open as a visitor attraction.

The abbey was founded in the 8th century and enlarged in the 10th. It wa ...

. Barrett endorsed the claims of the book and testified to Bond's sincerity. However, professional archaeologists and skeptics

Skepticism, also spelled scepticism, is a questioning attitude or doubt toward knowledge claims that are seen as mere belief or dogma. For example, if a person is skeptical about claims made by their government about an ongoing war then the pe ...

have found Bond's claims dubious.

In 1919, Barrett wrote the introduction to medium Hester Dowden's book ''Voices from the Void''.

Dowsing

Barrett held a special interest in divining rods and in 1897 and 1900 he published two articles on the subject in Proceedings of the SPR. He co-authored the book ''The Divining-Rod'' (1926), withTheodore Besterman

Theodore Deodatus Nathaniel Besterman (22 November 1904 – 10 November 1976) was a Polish-born British psychical researcher, bibliographer, biographer, and translator. In 1945 he became the first editor of the ''Journal of Documentation''. From ...

. Mill, Hugh Robert. (1927). ''Behind the Divining Rod''. ''Nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physics, physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomenon, phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. ...

'' 119: 310-311.

Barrett rejected any physical theory for dowsing

Dowsing is a type of divination employed in attempts to locate ground water, buried metals or ores, gemstones, oil, claimed radiations (radiesthesia),As translated from one preface of the Kassel experiments, "roughly 10,000 active dowsers in Ge ...

such as radiation. He concluded that the ideomotor response

The ideomotor phenomenon is a psychological phenomenon wherein a subject makes motions unconsciously. Also called ideomotor response (or ideomotor reflex) and abbreviated to IMR, it is a concept in hypnosis and psychological research. It is der ...

was responsible for the movement of the rod but in some cases the dowser's unconscious could pick up information by clairvoyance

Clairvoyance (; ) is the magical ability to gain information about an object, person, location, or physical event through extrasensory perception. Any person who is claimed to have such ability is said to be a clairvoyant () ("one who sees cl ...

.

Reception

Barrett has drawn criticism from researchers and skeptics as being overly credulous for endorsing spiritualist mediums and not detecting trickery that occurred in theséance

A séance or seance (; ) is an attempt to communicate with spirits. The word ''séance'' comes from the French word for "session", from the Old French ''seoir'', "to sit". In French, the word's meaning is quite general: one may, for example, spe ...

room. For example, author Ronald Pearsall

Ronald Joseph Pearsall (20 October 1927 – 27 September 2005) was an English writer whose scope included children's stories, pornography and fishing.

His most famous book ''The Worm in the Bud'' (1969) was about Victorian sexuality, including o ...

wrote that Barrett was duped into believing spiritualism by mediumship trickery.

Skeptic Edward Clodd

Edward Clodd (1 July 1840 – 16 March 1930) was an English banker, writer and anthropologist. He had a great variety of literary and scientific friends, who periodically met at Whitsunday (a springtime holiday) gatherings at his home at Aldeburg ...

criticized Barrett as being an incompetent researcher to detect fraud and claimed his spiritualist beliefs were based on magical thinking

Magical thinking, or superstitious thinking, is the belief that unrelated events are causally connected despite the absence of any plausible causal link between them, particularly as a result of supernatural effects. Examples include the idea that ...

and primitive superstition. Another skeptic Joseph McCabe

Joseph Martin McCabe (12 November 1867 – 10 January 1955) was an English writer and speaker on freethought, after having been a Roman Catholic priest earlier in his life. He was "one of the great mouthpieces of freethought in England". Becomi ...

wrote that Barrett "talks nonsense of which he ought to be ashamed" as he had poor understanding of conjuring

Conjuration or Conjuring may refer to:

__NOTOC__ Concepts

* Conjuration (summoning), the evocation of spirits or other supernatural entities

** Conjuration, a school of magic in ''Dungeons & Dragons''

* Conjuration (illusion), the performance of s ...

tricks and failed to detect the fraud of the medium Kathleen Goligher

Kathleen Goligher (born 1898) was an Irish spiritualist medium. Goligher was endorsed by engineer William Jackson Crawford who wrote three books about her mediumship, but was exposed as a fraud by physicist Edmund Edward Fournier d'Albe in 1921 ...

.

Psychical researcher Helen de G. Verrall gave Barrett's book ''Psychical Research'' a positive review describing it as a "clear, careful account of some of main achievements of psychical research by one who has himself taken part in these achievements and speaks to a large extent from personal knowledge and observation." However, in the ''British Medical Journal

''The BMJ'' is a weekly peer-reviewed medical trade journal, published by the trade union the British Medical Association (BMA). ''The BMJ'' has editorial freedom from the BMA. It is one of the world's oldest general medical journals. Origi ...

'' the book was criticized for ignoring critical work on the subject and being "a negative assault on scientific method generally".Anonymous (1912). ''A Study of Psychical Research''. ''British Medical Journal

''The BMJ'' is a weekly peer-reviewed medical trade journal, published by the trade union the British Medical Association (BMA). ''The BMJ'' has editorial freedom from the BMA. It is one of the world's oldest general medical journals. Origi ...

''. Vol. 1, No. 2667. pp. 308-309.

Bibliography

''Practical Physics: An Introductory Handbook for the Physical Laboratory.''

(1892) London: Percival & Co.

''On the Threshold of a New World of Thought: An Examination of the Phenomena of Spiritualism''

(1908) London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co.

''Psychical Research.

' (1911) New York: Henry Holt & Co. * ''Swedenborg: The Savant and the Seer.'' (1912) London: Watkins.

''On the Threshold of the Unseen: An Examination of the Phenomena of Spiritualism and of the Evidence for Survival After Death''

(1917) London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co.

Volltext

''The Divining Rod: An Experimental and Psychological Investigation.''

[with

Theodore Besterman

Theodore Deodatus Nathaniel Besterman (22 November 1904 – 10 November 1976) was a Polish-born British psychical researcher, bibliographer, biographer, and translator. In 1945 he became the first editor of the ''Journal of Documentation''. From ...

] (1926) London: Methuen & Co.

*''Christian Science: An Examination of the Religion of Health'' [with Rosa M. Barrett] (1926) New York: Henry Holt & Co.

* ''Deathbed Visions.'' (1926) London: Methuen & Co.

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Barrett, William F 1844 births 1925 deaths English physicists Fellows of the Royal Society Parapsychologists English spiritualists