William Armstrong (corn Merchant) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

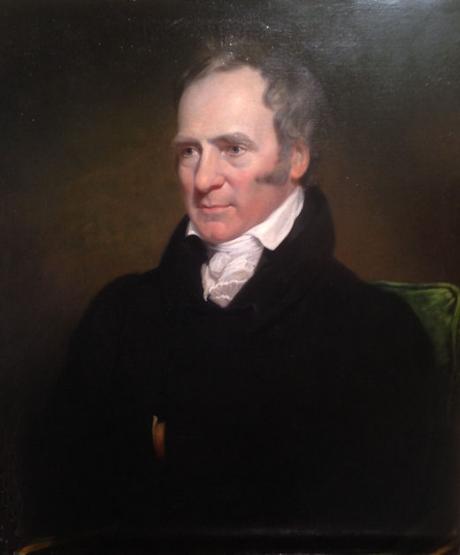

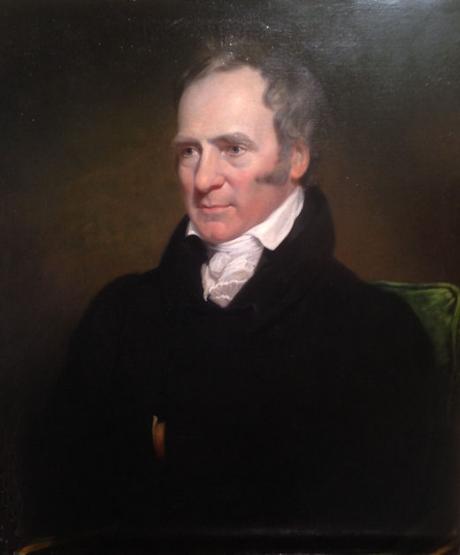

William Armstrong (1778–1857) was an English

Very little is known of Armstrong's early life. He was born in 1778, in the small village of

Very little is known of Armstrong's early life. He was born in 1778, in the small village of

In August 1824, Armstrong and Armorer Donkin, a close friend of Armstrong's, both with a passion for reform in their city, were appointed by the Moot Hall to a committee to recommend the construction of either a

In August 1824, Armstrong and Armorer Donkin, a close friend of Armstrong's, both with a passion for reform in their city, were appointed by the Moot Hall to a committee to recommend the construction of either a

Family tree of William Armstrong

{{DEFAULTSORT:Armstrong, William 1778 births 1857 deaths People from Cumberland Councillors in Newcastle upon Tyne Mayors of Newcastle upon Tyne

corn

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 10,000 years ago. Th ...

merchant

A merchant is a person who trades in commodities produced by other people, especially one who trades with foreign countries. Historically, a merchant is anyone who is involved in business or trade. Merchants have operated for as long as indust ...

and local politician of Newcastle-upon-Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne ( RP: , ), or simply Newcastle, is a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England. The city is located on the River Tyne's northern bank and forms the largest part of the Tyneside built-up area. Newcastle is als ...

. He was also the father of prominent industrialist William Armstrong, 1st Baron Armstrong

William George Armstrong, 1st Baron Armstrong, (26 November 1810 – 27 December 1900) was an English engineer and industrialist who founded the Armstrong Whitworth manufacturing concern on Tyneside. He was also an eminent scientist, inventor ...

.

Armstrong was born in a small Cumberland

Cumberland ( ) is a historic county in the far North West England. It covers part of the Lake District as well as the north Pennines and Solway Firth coast. Cumberland had an administrative function from the 12th century until 1974. From 19 ...

village, where he came in contact with the wealthy Losh family. This contact helped him gain a commercial foothold when he moved to Newcastle-upon-Tyne, joining a Losh-owned corn firm. Upon the proprietors' bankruptcy, Armstrong collected together the funds to establish his own corn firm: Armstrong, & Co.

Financially established, Armstrong was able to pursue his own interests. Armstrong took part local reformist politics, where he and his friends, James Losh

James Losh (1763–1833) was an English lawyer, reformer and Unitarian in Newcastle upon Tyne. In politics, he was a significant contact in the North East for the national Whig leadership. William Wordsworth the poet called Losh in a letter of 182 ...

and Armorer Donkin

Historically, an armourer is a person who makes personal armour, especially plate armour. In modern terms, an armourer is a member of a military or police force who works in an armoury and maintains and repairs small arms and weapons systems, w ...

, campaigned for parliamentary acts in Newcastle, and Armstrong attempted to reform the administration of the River Tyne

The River Tyne is a river in North East England. Its length (excluding tributaries) is . It is formed by the North Tyne and the South Tyne, which converge at Warden Rock near Hexham in Northumberland at a place dubbed 'The Meeting of the Wate ...

, to limited success. He entertained the local high society at the Newcastle Literary and Philosophical Society

The Literary and Philosophical Society of Newcastle upon Tyne (or the ''Lit & Phil'' as it is popularly known) is a historical library in Newcastle upon Tyne, England, and the largest independent library outside London. The library is still avai ...

, warmly supporting its growth. Armstrong also pursued a recreational mathematical interest, contributing to some minor journals, and leaving a large collection of mathematical volumes to the Society.

Early life and education

Very little is known of Armstrong's early life. He was born in 1778, in the small village of

Very little is known of Armstrong's early life. He was born in 1778, in the small village of Wreay

Wreay ( ) is a small English village that lies on the River Petteril in today's Cumbria. The M6 motorway, A6 trunk road and West Coast Main Line railway all skirt the village.

Governance

Wreay was once a civil parish, In 1931 it had a populat ...

, Cumbria

Cumbria ( ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in North West England, bordering Scotland. The county and Cumbria County Council, its local government, came into existence in 1974 after the passage of the Local Government Act 1972. Cumb ...

, the son of a local shoemaker, and descended from a long line of yeomen

Yeoman is a noun originally referring either to one who owns and cultivates land or to the middle ranks of servants in an English royal or noble household. The term was first documented in mid-14th-century England. The 14th century also witn ...

. Armstrong attended the local village school, developing an early interest in mathematics, and attending alongside the children of John Losh, from the local Losh family: James (1763–1833), George (1766–1846) and William. The Losh family were powerful in this area. They were descended from the Arloshes, who had occupied the area for over two centuries, and resided in the large local mansion known as Woodside. Though the family were never honoured with titles, John Losh was known locally as "the big black squire" of Woodside. At this school, Armstrong was tutored by the local priest, William Gaskin, an eccentric man whom James Losh recalled as "uncouth in his manners and abrupt and confused in his manner of speaking", if also "a man of considerable powers of mind". Armstrong was also likely introduced to the celebrated mathematics teacher, John Dawson, by John and James Losh, who both later studied under him at Sedbergh School

Sedbergh School is a public school (English independent day and boarding school) in the town of Sedbergh in Cumbria, in North West England. It comprises a junior school for children aged 4 to 13 and the main school for 13 to 18 year olds. It w ...

.

Career as a corn merchant

In the mid-1790s, Armstrong arrived inNewcastle upon Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne ( RP: , ), or simply Newcastle, is a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England. The city is located on the River Tyne's northern bank and forms the largest part of the Tyneside built-up area. Newcastle is ...

, promptly joining Losh, Lubbren & Co, a Quayside

The Quayside is an area along the banks (quay) of the River Tyne in Newcastle upon Tyne (the north bank) and Gateshead (south bank) in Tyne and Wear, North East England, United Kingdom.

History

The area was once an industrial area and busy com ...

firm of corn merchants, as a clerk

A clerk is a white-collar worker who conducts general office tasks, or a worker who performs similar sales-related tasks in a retail environment. The responsibilities of clerical workers commonly include record keeping, filing, staffing service ...

in the firm's counting house. George Losh was here, a senior partner in the firm, alongside the naturalised

Naturalization (or naturalisation) is the legal act or process by which a non-citizen of a country may acquire citizenship or nationality of that country. It may be done automatically by a statute, i.e., without any effort on the part of the i ...

German merchant, John Diedrich Lubbren. The Losh family had grown powerful in Newcastle, with George also owning the local Newcastle Fire Office and Water Company, and his brothers - William and James - later becoming influential members of Tyneside

Tyneside is a built-up area across the banks of the River Tyne in northern England. Residents of the area are commonly referred to as Geordies. The whole area is surrounded by the North East Green Belt.

The population of Tyneside as published i ...

's high society. In Summer 1803, the firm went bankrupt, when the abrupt collapse of the Newcastle banking house, Surtrees and Burdon, left George Losh and his partners financially embarrassed, the first of a series of failures that led Losh to migrate to France. Armstrong - then married and with one daughter - was forced to rely on financial support from his wife's family, Diedrich Lubbren, and possibly William Losh, using the funds to start his own enterprise in the corn industry: "Armstrong & Co., merchants, Cowgate

The Cowgate (Scots language, Scots: The Cougait) is a street in Edinburgh, Scotland, located about southeast of Edinburgh Castle, within the city's World Heritage Site. The street is part of the lower level of Edinburgh's Old Town, Edinburgh, ...

".

Career as a local politician

In August 1824, Armstrong and Armorer Donkin, a close friend of Armstrong's, both with a passion for reform in their city, were appointed by the Moot Hall to a committee to recommend the construction of either a

In August 1824, Armstrong and Armorer Donkin, a close friend of Armstrong's, both with a passion for reform in their city, were appointed by the Moot Hall to a committee to recommend the construction of either a horse-drawn railway

Wagonways (also spelt Waggonways), also known as horse-drawn railways and horse-drawn railroad consisted of the horses, equipment and tracks used for hauling wagons, which preceded steam-powered railways. The terms plateway, tramway, dramway, ...

or canal between Newcastle and Carlisle. Armstrong clearly saw the importance of his duty, noting: "We can bring corn from the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is t ...

to Newcastle cheaper than we can convey it between Newcastle and Carlisle". Armstrong was cautious of a railway system, as a relatively new form of transport, referring to the plan as "spiritless". This argument did not meet with agreement on the committee, and the following year, it recommended the construction of the Newcastle & Carlisle Railway

The Newcastle & Carlisle Railway (N&CR) was an English railway company formed in 1825 that built a line from Newcastle upon Tyne on Britain's east coast, to Carlisle, on the west coast. The railway began operating mineral trains in 1834 between ...

, headed by the more radical reformer, James Losh. This preference has variously been suggested as evidence of his innate fear of new technology, or his rational preference as a cautious corn merchant, wanting his stock to be carried in more safe and established modes of transport.

In 1831, Armstrong, James Losh, and Donkin attended Northumberland

Northumberland () is a county in Northern England, one of two counties in England which border with Scotland. Notable landmarks in the county include Alnwick Castle, Bamburgh Castle, Hadrian's Wall and Hexham Abbey.

It is bordered by land on ...

reform meeting in support of the Great Reform Act

The Representation of the People Act 1832 (also known as the 1832 Reform Act, Great Reform Act or First Reform Act) was an Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom (indexed as 2 & 3 Will. IV c. 45) that introduced major changes to the electo ...

- a wide-ranging democratic act of parliament, which had met with much opposition - and supporting a resolution against the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the Bicameralism, upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by Life peer, appointment, Hereditary peer, heredity or Lords Spiritual, official function. Like the ...

, who had most vigorously opposed the act. After the Municipal Corporations Act 1835

The Municipal Corporations Act 1835 (5 & 6 Will 4 c 76), sometimes known as the Municipal Reform Act, was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that reformed local government in the incorporated boroughs of England and Wales. The legisl ...

, which reformed the governance of local boroughs, Armstrong was elected as a reformist candidate in the Newcastle town council, an office he attained with a substantial majority against the reactionary, Matthew Anderson. At the council, Armstrong voted in favour of the removal of the furniture and fittings of the Mayor's residence, and the end of the tradition of the Mayor's feasts, held at the public expense. His success didn't sustain in the following, 1839 election, where he was defeated by a landslide by the "more formidable opponent", George Palmer, losing his seat 38 votes to 8. With Palmer's retirement, Armstrong returned to the office in 1842, unopposed. In January 1849, upon the vacancy of a seat, he was unanimously elected an alderman of Newcastle. The aldermen were not so harmonious when, a few months later, he was proposed to be made the mayor of Newcastle, as the queen was expected to visit the town soon. The better known watercolourist, Joseph Crawhall II

Joseph Crawhall II (1821–1896) was born at West House, Newcastle. He was a ropemaker, author, and watercolour painter.

Life

Crawhall, like his father (also Joseph), a Newcastle ropemaker, was interested in writing and watercolour painting. He ...

was selected in his stead to preside over the royal visit. By November the following year, Armstrong was elected mayor; he led a mayoralty described by local historian Richard Welford as "quiet and uneventful", in which Armstrong led the "usual festivities" and "presided over the usual number of public meetings".

Armstrong was generally a progressive, but began as a more independent, and sometimes reactionary, politician, remaining a "timid reformer" even afterwards, according to Welford. In the 1832 general election he voted for both Tory

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. Th ...

and Whig Newcastle MP candidates. By the 1835 election, he was decidedly in favour of the Whigs. By 1837, he was divided between two candidates - Charles John Bigge and William Ord - after which he expressly favoured Whig (or, later, Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

) candidates. One political concern he held, despite his reformist reputation, was against the abolition of the Corn Laws

The Corn Laws were tariffs and other trade restrictions on imported food and corn enforced in the United Kingdom between 1815 and 1846. The word ''corn'' in British English denotes all cereal grains, including wheat, oats and barley. They were ...

- a set of taxes on imported food, which kept domestic grain prices high - a reform he spoke out vigorously against in 1845, perhaps out of self interest as a corn merchant.

While a local politician, Armstrong primarily concerned himself with the management of the River Tyne

The River Tyne is a river in North East England. Its length (excluding tributaries) is . It is formed by the North Tyne and the South Tyne, which converge at Warden Rock near Hexham in Northumberland at a place dubbed 'The Meeting of the Wate ...

. Before the 1835 Act, the council had been derided for its neglect of the river, and many hoped the new council would attend to its problems. In his first term as councillor, Armstrong issued a polemical pamphlet of his observations on the river's improvement, and in 1843, promptly took over the local River Committee, upon the previous chairman's death. Despite the many heated debates Armstrong held on it, "neither he nor the council's appointed engineer had the skills needed to enable a programme of improvement to be pursued with any degree of confidence", according to Stafford M. Linsley, writing for the ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

''. Armstrong's incompetence, as well as the widespread belief that the Committee's funds were being inappropriately used, led to agitation against the Committee, especially from those heavily economically invested in the river, as in North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating Direction (geometry), direction or geography.

Etymology

T ...

and South Shields

South Shields () is a coastal town in South Tyneside, Tyne and Wear, England. It is on the south bank of the mouth of the River Tyne. Historically, it was known in Roman times as Arbeia, and as Caer Urfa by Early Middle Ages. According to the 20 ...

. Armstrong held this position, continuing his demands for reformation, which invariably met with the formidable opposition of the council, until the Tyne Improvement Act of 1850 was passed. This act dismantled the council's authority over the river, instead putting it under the control of a group of commissioners. The bill was put forth to the House of Commons in June 1850, naming Armstrong as one of the life commissioners, but, after complaints from the council, Armstrong's name was substituted for that of William Rutherford Hunter before the bill was presented to the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the Bicameralism, upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by Life peer, appointment, Hereditary peer, heredity or Lords Spiritual, official function. Like the ...

.

Personal life and death

Around 1801, Armstrong married Ann Potter, the eldest daughter of William Potter of Walbottle House, and a "highly cultured woman" according to Henry Palin Gurney, writing for the ''Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

''. They had two children, a daughter and a son. The daughter, Ann, the eldest of the two, married William Henry Watson

Sir William Henry Watson QC (1 July 1796 – 13 March 1860), was a British politician and judge.

Life Early life

Watson was born at Nottingham, the son of John Watson, captain in the 76th Foot, by Elizabeth, daughter of Henry Grey of Bamburgh ...

, a minor politician and judge. The son, William, later to become first Baron Armstrong, was a prominent industrialist, scientist, and inventor. The Armstrong household allowed William to nurture an early mechanical interest, often visiting the joiner

A joiner is an artisan and tradesperson who builds things by joining pieces of wood, particularly lighter and more ornamental work than that done by a carpenter, including furniture and the "fittings" of a house, ship, etc. Joiners may work in ...

employed by William Potter for lessons in mechanics. The family initially lived in a three-storey terraced house on 9 Pleasant Row, Shieldfield, where his son, William was born, and spent his early childhood, developing a passion for water and fishing. The house no longer exists, but the remaining lintel

A lintel or lintol is a type of beam (a horizontal structural element) that spans openings such as portals, doors, windows and fireplaces. It can be a decorative architectural element, or a combined ornamented structural item. In the case of w ...

refers to the establishment as the 'Armstrong House', and a stone adjacent to Christ Church, Shieldfield, commemorates it. By the 1820s, with Armstrong's trade flourishing, the family moved to a larger, 12 acre establishment in Ouseburn Valley

The Ouseburn Valley is the name of the valley of the Ouseburn, a small tributary of the River Tyne, running southwards through the east of Newcastle upon Tyne, England. The name refers particularly to the urbanised lower valley, spanned by thr ...

, where Armstrong built a house, known as South Jesmond House.

His financial success in the corn industry allowed Armstrong to pursue several personal interests, including a passion for mathematics. He contributed to the recreational mathematics journals, ''The Ladies' Diary

''The Ladies' Diary: or, Woman's Almanack'' appeared annually in London from 1704 to 1841 after which it was succeeded by ''The Lady's and Gentleman's Diary''. It featured material relating to calendars etc. including sunrise and sunset times an ...

'' and ''Gentleman's Diary ''Gentleman's Diary or The Mathematical Repository'' was (a supplement to) an almanac published at the end of the 18th century in England, including mathematical problems.

The supplement was also known as: ''"The mathematical repository: an almana ...

'', and collected a large mathematical library. Armstrong joined the recently founded Newcastle Literary and Philosophical Society in 1798, "a warm supporter of the institution and man of scholarly acquirements" according to a contemporary, and helped found the local Natural History Society. He also provided funds for the establishment of a local chamber of commerce

A chamber of commerce, or board of trade, is a form of business network. For example, a local organization of businesses whose goal is to further the interests of businesses. Business owners in towns and cities form these local societies to ad ...

, where he served on the committee. At the Literary and Philosophical Society, Armstrong became close friends with the local solicitor, Armorer Donkin. "Their tastes were similar; their political views harmonized; their aims were practically identical, and they became as brothers" according to local historian, Alfred Cochrane. Donkin remained a family friend and, later in his life, took the younger William as an apprentice.

Armstrong died on 2 June 1857, having given up many of his offices weeks earlier. Armstrong requested that his son, William, leave his large library of mathematical and local tracts to the Literary and Philosophical Society, a wish William fulfilled the following year, with 1284 works added to the society's libraries. This allowed the society "a more complete mathematical department than any other provincial institution in the kingdom" according to Dr. Robert Spence Watson

Robert Spence Watson (8 June 1837 – 2 March 1911) was an English solicitor, reformer, politician and writer. He became famous for pioneering labour arbitrations.

Life and career

He was born in Gateshead, the second child of Sarah (Spence) an ...

, Secretary of the Society, 1862–93. Armstrong was buried in the local Jesmond Old Cemetery

Jesmond Old Cemetery is a Victorian cemetery in Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom, founded in 1834. It contains two Grade II listed buildings and seven Grade II listed monuments as well as the graves of dozens of notable people from the history ...

, in the same grave as his wife, who had predeceased him on 8 June 1848, and next to the grave of Armorer Donkin, who had died in 1851. Armstrong and Donkin's graves are, aside from their inscriptions, identical, with the twin low, cruciform

Cruciform is a term for physical manifestations resembling a common cross or Christian cross. The label can be extended to architectural shapes, biology, art, and design.

Cruciform architectural plan

Christian churches are commonly described ...

, granite structures likely designed by the younger Armstrong.

References

Sources

* * * * * * *Further reading

On Armstrong * * On Armstrong's son, containing information on Armstrong * *External links

Family tree of William Armstrong

{{DEFAULTSORT:Armstrong, William 1778 births 1857 deaths People from Cumberland Councillors in Newcastle upon Tyne Mayors of Newcastle upon Tyne