William Adams (pilot) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

(24 September 1564 – 16 May 1620), better known in Japanese as , was an English

Chapter Five

/ref>

Attracted by the

Attracted by the  After leaving

After leaving

When finally the Pacific Ocean was reached on 3 September 1599, the ships were caught in a storm and lost sight of each other. The "Loyalty" and the "Believe" were driven back in the strait. After more than a year each ship went its own way.

The ''Geloof'' returned to Rotterdam in July 1600 with 36 men surviving of the original 109 crew.

De Cordes ordered his small fleet to wait four weeks for each other on

When finally the Pacific Ocean was reached on 3 September 1599, the ships were caught in a storm and lost sight of each other. The "Loyalty" and the "Believe" were driven back in the strait. After more than a year each ship went its own way.

The ''Geloof'' returned to Rotterdam in July 1600 with 36 men surviving of the original 109 crew.

De Cordes ordered his small fleet to wait four weeks for each other on  During the voyage, before December 1598, Adams changed ships to the ''Liefde'' (originally named ''Erasmus'' and adorned by a wooden carving of

During the voyage, before December 1598, Adams changed ships to the ''Liefde'' (originally named ''Erasmus'' and adorned by a wooden carving of

In April 1600, after more than 19 months at sea, a crew of 23 sick and dying men (out of the 100 who started the voyage) brought the ''Liefde'' to anchor off the island of

In April 1600, after more than 19 months at sea, a crew of 23 sick and dying men (out of the 100 who started the voyage) brought the ''Liefde'' to anchor off the island of

Adams had a wife Mary Hyn and two children back in England, but Ieyasu forbade the Englishman to leave Japan. He was presented with two swords representing the authority of a

Adams had a wife Mary Hyn and two children back in England, but Ieyasu forbade the Englishman to leave Japan. He was presented with two swords representing the authority of a

In 1604 Ieyasu sent the ''Liefdes captain,

In 1604 Ieyasu sent the ''Liefdes captain,  Hampered by conflicts with the Portuguese and limited resources in Asia, the Dutch were not able to send ships to Japan until 1609. Two Dutch ships, commanded by

Hampered by conflicts with the Portuguese and limited resources in Asia, the Dutch were not able to send ships to Japan until 1609. Two Dutch ships, commanded by  After obtaining this trading right through an edict of Tokugawa Ieyasu on 24 August 1609, the Dutch inaugurated a trading factory in

After obtaining this trading right through an edict of Tokugawa Ieyasu on 24 August 1609, the Dutch inaugurated a trading factory in

In 1613, the English captain

In 1613, the English captain  Adams traveled with Saris to Suruga, where they met with Ieyasu at his principal residence in September. The Englishmen continued to

Adams traveled with Saris to Suruga, where they met with Ieyasu at his principal residence in September. The Englishmen continued to  Adams accepted employment with the newly founded Hirado trading factory, signing a contract on 24November 1613, with the East India Company for the yearly salary of 100 English Pounds. This was more than double the regular salary of 40 Pounds earned by the other factors at Hirado. Adams had a lead role, under

Adams accepted employment with the newly founded Hirado trading factory, signing a contract on 24November 1613, with the East India Company for the yearly salary of 100 English Pounds. This was more than double the regular salary of 40 Pounds earned by the other factors at Hirado. Adams had a lead role, under

Adams later engaged in various exploratory and commercial ventures. He tried to organise an expedition to the legendary

Adams later engaged in various exploratory and commercial ventures. He tried to organise an expedition to the legendary

* A town in Edo (modern Tokyo), Anjin-chō (in modern-day

* A town in Edo (modern Tokyo), Anjin-chō (in modern-day

William Adams was buried in 1620, in Hirado, Nagasaki Prefecture. However, a few years later foreign cemeteries were destroyed and there was prosecution of Christians by the

William Adams was buried in 1620, in Hirado, Nagasaki Prefecture. However, a few years later foreign cemeteries were destroyed and there was prosecution of Christians by the

Sir Ernest M. Satow

(Hakluyt Society, 1900) * ''Asiatic Society of Japan Transactions'', xxvi. (sec. 1898) pp. I and 194, where four formerly unpublished letters of Adams are printed; * ''Collection of State Papers; East Indies, China and Japan.'' The MS. of his logs written during his voyages to Siam and China is in the Bodleian Library at Oxford. * ''Samurai William: The Adventurer Who Unlocked Japan'', by

* ''Adams the Pilot: The Life and Times of Captain William Adams: 1564–1620'', by William Corr, Curzon Press, 1995 * ''The English Factory in Japan 1613–1623'', ed. by Anthony Farrington, British Library, 1991. (Includes all of William Adams' extant letters, as well as his will.) * ''A World Elsewhere. Europe’s Encounter with Japan in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries'', by Derek Massarella, Yale University Press, 1990. * ''Recollections of Japan'', Hendrik Doeff,

Williams Adams- Blue Eyed Samurai, Meeting Anjin

"Learning from Shogun. Japanese history and Western fantasy"

William Adams and Early English enterprise in Japan

William Adams – The First Englishman In Japan

full text online, Internet Archive

Will Adams Memorial

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Adams, William Samurai Foreign samurai in Japan 1564 births 1620 deaths 16th-century English people 17th-century English people 16th-century Japanese people 17th-century Japanese people Advisors to Tokugawa shoguns English emigrants to Japan English Anglicans English sailors Hatamoto Japan–United Kingdom relations People from Gillingham, Kent Royal Navy officers Sailors on ships of the Dutch East India Company Foreign relations of the Tokugawa shogunate

navigator

A navigator is the person on board a ship or aircraft responsible for its navigation.Grierson, MikeAviation History—Demise of the Flight Navigator FrancoFlyers.org website, October 14, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2014. The navigator's primar ...

who, in 1600, was the first Englishman to reach Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

in a ship called 'de Liefde' under the leadership of Jacob Quaeckernaeck, the only surviving ship of a five-ship expedition launched by a Rotterdam East India company(which would later be amalgamated into the United East India Company, the VOC). Of the few survivors of the only ship that reached Japan, Adams and his second mate Jan Joosten

Jan Joosten van Lodensteyn (or Lodensteijn; 1556–1623), known in Japanese as Yayōsu (耶楊子), was a native of Delft and one of the first Dutchmen in Japan, and the second mate on the Dutch ship ''De Liefde'', which was stranded in Japan i ...

were not allowed to leave the country while Jacob Quaeckernaeck

Jacob Jansz. Quaeckernaeck (or ''Quackernaeck'' or ''Kwakernaak'') (ca. 1543 – 21 September 1606) was a native of Rotterdam and one of the first Dutchmen in Japan, and he was a navigator and later the captain (after the death of the previous ...

and Melchior van Santvoort were permitted to go back to the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands (Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiography ...

to invite them to trade.

Adams, along with former second mate Joosten, then settled in Japan, and the two became some of the first (of very few) Western samurai.

Soon after Adams' arrival in Japan, he became a key advisor to the ''shōgun

, officially , was the title of the military dictators of Japan during most of the period spanning from 1185 to 1868. Nominally appointed by the Emperor, shoguns were usually the de facto rulers of the country, though during part of the Kamakur ...

'' Tokugawa Ieyasu

was the founder and first ''shōgun'' of the Tokugawa Shogunate of Japan, which ruled Japan from 1603 until the Meiji Restoration in 1868. He was one of the three "Great Unifiers" of Japan, along with his former lord Oda Nobunaga and fellow ...

. Adams directed construction for the shōgun of the first Western-style ships in the country. He was later part of Japan's approving the establishment of trading factories by the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

. He was also highly involved in Japan's Red Seal Asian trade, chartering and serving as captain of four expeditions to Southeast Asia. He died in Japan at age 55. He has been recognised as one of the most influential foreigners in Japan during this period.

Early life

Adams was born inGillingham, Kent

Gillingham ( ) is a large town in the unitary authority area of Medway in the ceremonial county of Kent, England. The town forms a conurbation with neighbouring towns Chatham, Rochester, Strood and Rainham. It is also the largest town in the ...

, England. When Adams was twelve his father died, and he was apprenticed to shipyard owner Master Nicholas Diggins at Limehouse

Limehouse is a district in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets in East London. It is east of Charing Cross, on the northern bank of the River Thames. Its proximity to the river has given it a strong maritime character, which it retains throug ...

for the seafaring life. He spent the next twelve years learning shipbuilding

Shipbuilding is the construction of ships and other floating vessels. It normally takes place in a specialized facility known as a shipyard. Shipbuilders, also called shipwrights, follow a specialized occupation that traces its roots to befor ...

,Giles Milton, ''Samurai William: The Adventurer Who Unlocked Japan'', 2011, Hachette UK, , Chapter Five

/ref>

astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

, and navigation

Navigation is a field of study that focuses on the process of monitoring and controlling the movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another.Bowditch, 2003:799. The field of navigation includes four general categories: land navigation, ...

before entering the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

.

With England at war with Spain, Adams served in the Royal Navy under Sir Francis Drake

Sir Francis Drake ( – 28 January 1596) was an English explorer, sea captain, privateer, slave trader, naval officer, and politician. Drake is best known for his circumnavigation of the world in a single expedition, from 1577 to 1580 (t ...

. He saw naval service against the Spanish Armada

The Spanish Armada (a.k.a. the Enterprise of England, es, Grande y Felicísima Armada, links=no, lit=Great and Most Fortunate Navy) was a Spanish fleet that sailed from Lisbon in late May 1588, commanded by the Duke of Medina Sidonia, an aris ...

in 1588 as master of the ''Richarde Dyffylde'', a resupply ship. Adams was recorded to have married Mary Hyn in the parish church of St Dunstan's, Stepney

St Dunstan's, Stepney, is an Anglican Church which stands on a site that has been used for Christian worship for over a thousand years. It is located in Stepney High Street, in Stepney, London Borough of Tower Hamlets.

History

In about AD 952, D ...

on 20 August 1589 and they had two children: a son John and a daughter named Deliverance. Soon after, Adams became a pilot for the Barbary Company

The Marocco Company or Barbary Company was a trading company established by Queen Elizabeth I of England in 1585 through a patent granted to the Earls of Warwick and Leicester, as well as forty others. When she wrote the patents, Elizabeth emphasi ...

. During this service, Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

sources claim he took part in an expedition to the Arctic

The Arctic ( or ) is a polar regions of Earth, polar region located at the northernmost part of Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean, adjacent seas, and parts of Canada (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut), Danish Realm (Greenla ...

that lasted about two years, in search of a Northeast Passage

The Northeast Passage (abbreviated as NEP) is the shipping route between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, along the Arctic coasts of Norway and Russia. The western route through the islands of Canada is accordingly called the Northwest Passage (N ...

along the coast of Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part of ...

to the Far East. The veracity of this claim is somewhat suspect, because he never referred to such an expedition in his autobiographical letter written from Japan; its wording implies that the 1598 voyage was his first involvement with the Dutch. The Jesuit source may have misattributed to Adams a claim by one of the Dutch members of Mahu's crew who had been on Rijp's ship during the voyage that discovered Spitsbergen

Spitsbergen (; formerly known as West Spitsbergen; Norwegian: ''Vest Spitsbergen'' or ''Vestspitsbergen'' , also sometimes spelled Spitzbergen) is the largest and the only permanently populated island of the Svalbard archipelago in northern Norw ...

.

Expedition to the Far East

Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

trade with India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, Adams, then 34 years old, shipped as pilot major with a five-ship fleet dispatched from the isle of Texel

Texel (; Texels dialect: ) is a municipality and an island with a population of 13,643 in North Holland, Netherlands. It is the largest and most populated island of the West Frisian Islands in the Wadden Sea. The island is situated north of De ...

to the Far East in 1598 by a company of Rotterdam

Rotterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Rotte'') is the second largest city and municipality in the Netherlands. It is in the province of South Holland, part of the North Sea mouth of the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta, via the ''"N ...

merchants (a ''voorcompagnie

A voorcompagnie (pre-company) is the naming given to the trading companies from the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands that traded in Asia between 1594 and 1602, before they all merged to form the Dutch East India Company (VOC). The pre-compa ...

,'' predecessor of the Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( nl, Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the VOC) was a chartered company established on the 20th March 1602 by the States General of the Netherlands amalgamating existing companies into the first joint-stock ...

). His brother Thomas accompanied him. The Dutch were allied with England at that time; both were Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

nations, and were fighting against Spain for Dutch independence.

The Adams brothers set sail from Texel on the ''Hoope'' and joined with the rest of the fleet on 24 June. The fleet consisted of:

* the ''Hoope'' ("Hope"), under Admiral Jacques Mahu

Jacob (Jacques) Mahu (1564 – 23 September 1598) was a Dutch merchant and explorer.

In 1598, he led an expedition with five vessels organised by Pieter van der Hagen and Johan van der Veeken intended to find a trade route to the Spice Islands a ...

(d. 1598), he was succeeded by Simon de Cordes

Simon de Cordes (born around 1559 – died 11 November 1599) was a Dutch merchant and explorer who after the death of Admiral Jacques Mahu, became leader of an expedition with the goal to achieve the Indies,DE REIS VAN MAHU EN DE CORDES DOOR DE ...

(d. 1599) and Simon de Cordes Jr. This ship was lost near the Hawaiian Islands

The Hawaiian Islands ( haw, Nā Mokupuni o Hawai‘i) are an archipelago of eight major islands, several atolls, and numerous smaller islets in the North Pacific Ocean, extending some from the island of Hawaii in the south to northernmost Kur ...

;

* the ''Liefde'' ("Love" or "Charity"), under Simon de Cordes, 2nd in command, succeeded by Gerrit van Beuningen

Gerrit is a Dutch male name meaning "''brave with the spear''", the Dutch and Frisian form of Gerard. People with this name include:

* Gerrit Achterberg (1905–1962), Dutch poet

* Gerrit van Arkel (1858–1918), Dutch architect

* Gerrit Baden ...

and finally under Jacob Kwakernaak; this was the only ship which reached Japan

* the ''Geloof'' ("Faith"), under Gerrit van Beuningen, and in the end, Sebald de Weert

Sebald or Sebalt de Weert (May 2, 1567 – May 30 or June 1603) was a Flemish captain and vice-admiral of the Dutch East India Company (known in Dutch as ''Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie'', VOC). He is most widely remembered for accurately p ...

; the only ship which came back in Rotterdam.

* the ''Trouw'' ("Loyalty"), under Jurriaan van Boekhout (d. 1599) and finally, Baltazar de Cordes

Baltazar de Cordes (16th century–17th century), the brother of Simon de Cordes, was a Dutch corsair who fought against the Spanish during the early 17th century.

Born in the Netherlands in the mid-16th century, Cordes began sailing for the ...

; was captured in Tidore

Tidore ( id, Kota Tidore Kepulauan, lit. "City of Tidore Islands") is a city, island, and archipelago in the Maluku Islands of eastern Indonesia, west of the larger island of Halmahera. Part of North Maluku Province, the city includes the island ...

.

* the ''Blijde Boodschap'' ("Good Tiding" or "The Gospel"), under Sebald de Weert, and later, Dirck Gerritz was seized in Valparaiso.

Jacques Mahu

Jacob (Jacques) Mahu (1564 – 23 September 1598) was a Dutch merchant and explorer.

In 1598, he led an expedition with five vessels organised by Pieter van der Hagen and Johan van der Veeken intended to find a trade route to the Spice Islands a ...

and Simon de Cordes

Simon de Cordes (born around 1559 – died 11 November 1599) was a Dutch merchant and explorer who after the death of Admiral Jacques Mahu, became leader of an expedition with the goal to achieve the Indies,DE REIS VAN MAHU EN DE CORDES DOOR DE ...

were the leaders of an expedition with the goal to achieve the Chile, Peru and other kingdoms (in New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( es, Virreinato de Nueva España, ), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the Am ...

like Nueva Galicia

Nuevo Reino de Galicia (''New Kingdom of Galicia'', gl, Reino de Nova Galicia) or simply Nueva Galicia (''New Galicia'', ''Nova Galicia'') was an autonomous kingdom of the Viceroyalty of New Spain. It was named after Galicia in Spain. Nueva ...

; Captaincy General of Guatemala

The Captaincy General of Guatemala ( es, Capitanía General de Guatemala), also known as the Kingdom of Guatemala ( es, Reino de Guatemala), was an administrative division of the Spanish Empire, under the viceroyalty of New Spain in Central A ...

; Nueva Vizcaya

Nueva Vizcaya, officially the Province of Nueva Vizcaya ( ilo, Probinsia ti Nueva Vizcaya; gad, Probinsia na Nueva Vizcaya; Pangasinan: ''Luyag/Probinsia na Nueva Vizcaya''; tl, Lalawigan ng Nueva Vizcaya ), is a landlocked province in the ...

; New Kingdom of León

The New Kingdom of León ( es, Nuevo Reino de León), was an administrative territory of the Spanish Empire, politically ruled by the Viceroyalty of New Spain. It was located in an area corresponding generally to the present-day northeastern Mexica ...

and Santa Fe de Nuevo México

Santa Fe de Nuevo México ( en, Holy Faith of New Mexico; shortened as Nuevo México or Nuevo Méjico, and translated as New Mexico in English) was a Kingdom of the Spanish Empire and New Spain, and later a territory of independent Mexico. The ...

). The fleet's original mission was to sail for the west coast of South America, where they would sell their cargo for silver, and to head for Japan only if the first mission failed. In that case, they were supposed to obtain silver in Japan and to buy spices in the Moluccas

The Maluku Islands (; Indonesian: ''Kepulauan Maluku'') or the Moluccas () are an archipelago in the east of Indonesia. Tectonically they are located on the Halmahera Plate within the Molucca Sea Collision Zone. Geographically they are located eas ...

, before heading back to Europe. Their goal was to sail through the Strait of Magellan

The Strait of Magellan (), also called the Straits of Magellan, is a navigable sea route in southern Chile separating mainland South America to the north and Tierra del Fuego to the south. The strait is considered the most important natural pass ...

to get to their destiny, which scared many sailors because of the harsh weather conditions. The first major expedition around South America was organized by a voorcompagnie

A voorcompagnie (pre-company) is the naming given to the trading companies from the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands that traded in Asia between 1594 and 1602, before they all merged to form the Dutch East India Company (VOC). The pre-compa ...

, the Rotterdam or Magelhaen Company. It organized two fleets of five and four ships with 750 sailors and soldiers, including 30 English musicians.

After leaving

After leaving Goeree

Goeree-Overflakkee () is the southernmost delta

Delta commonly refers to:

* Delta (letter) (Δ or δ), a letter of the Greek alphabet

* River delta, at a river mouth

* D ( NATO phonetic alphabet: "Delta")

* Delta Air Lines, US

* Delta variant ...

on 27 June 1598 the ships sailed to the Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

, but anchored in the Downs till mid July. When the ships approached the shores of North Africa Simon de Cordes realized he had been far too generous in the early weeks of the voyage and instituted a 'bread policy'. At the end of August they landed on Santiago, Cape Verde

Santiago (Portuguese for “ Saint James”) is the largest island of Cape Verde, its most important agricultural centre and home to half the nation's population. Part of the Sotavento Islands, it lies between the islands of Maio ( to the east) ...

and Mayo Mayo often refers to:

* Mayonnaise, often shortened to "mayo"

* Mayo Clinic, a medical center in Rochester, Minnesota, United States

Mayo may also refer to:

Places

Antarctica

* Mayo Peak, Marie Byrd Land

Australia

* Division of Mayo, an Aust ...

off the coast of Africa because of a lack of water and need for fresh fruit. They stayed around three weeks in the hope to buy some goats. Near Praia

Praia (, Portuguese language, Portuguese for "beach") is the capital and largest city of Cape Verde.

they succeeded to occupy a Portuguese castle on the top of a hill, but came back without anything substantial. At Brava, Cape Verde

Brava (Portuguese for "wild" or "brave") is an island in Cape Verde, in the Sotavento group. At , it is the smallest inhabited island of the Cape Verde archipelago, but at the same time the greenest. First settled in the early 16th century, it ...

half of the crew of the "Hope" caught fever there, with most of the men sick, among them Admiral Jacques Mahu. After his death the leadership of the expedition was taken over by Simon de Cordes, with Van Beuningen as vice admiral. Because of contrary wind the fleet was blown off course

To be blown off course in the sailing ship era meant be to diverted by unexpected winds, getting lost possibly to shipwreck or to a new destination. In the ancient world, this was especially a great danger before the maturation of the Maritime S ...

(NE in the opposite direction) and arrived at Cape Lopez

Cape Lopez () is a headland on the coast of Gabon, west central Africa. The westernmost point of Gabon, it separates the Gulf of Guinea from the South Atlantic Ocean. Cape Lopez is the northernmost point of a low, wooded island between two mouths ...

, Gabon

Gabon (; ; snq, Ngabu), officially the Gabonese Republic (french: République gabonaise), is a country on the west coast of Central Africa. Located on the equator, it is bordered by Equatorial Guinea to the northwest, Cameroon to the north ...

, Central Africa.Samurai William: The Adventurer Who Unlocked Japan by Giles Milton An outbreak of scurvy forced a landing on Annobón

Annobón ( es, Provincia de Annobón; pt, Ano-Bom), and formerly as ''Anno Bom'' and ''Annabona'', is a province (smallest province in both area and population) of Equatorial Guinea consisting of the island of Annobón, formerly also Pigalu a ...

, on 9 December. Several men became sick because of dysentery. They stormed the island only to find that the Portuguese and their native allies had set fire to their own houses and fled into the hills. They put all the sick ashore to recover and left early January. Because of starvation the men fell into great weakness; some tried to eat leather. On 10 March 1599 they reached the Rio de la Plata

Rio or Río is the Portuguese, Spanish, Italian, and Maltese word for "river". When spoken on its own, the word often means Rio de Janeiro, a major city in Brazil.

Rio or Río may also refer to:

Geography Brazil

* Rio de Janeiro

* Rio do Sul, a ...

, in Argentina. Early April they arrived at the Strait, 570 km long, 2 km wide at its narrowest point, with an inaccurate chart of the seabed. The wind turned out to be unfavorable and this remained so for the next four months. Under freezing temperatures and poor visibility they caught penguins, seals, mussels, duck and fish. About two hundred crew members died. On 23 August the weather improved.

On the Pacific

When finally the Pacific Ocean was reached on 3 September 1599, the ships were caught in a storm and lost sight of each other. The "Loyalty" and the "Believe" were driven back in the strait. After more than a year each ship went its own way.

The ''Geloof'' returned to Rotterdam in July 1600 with 36 men surviving of the original 109 crew.

De Cordes ordered his small fleet to wait four weeks for each other on

When finally the Pacific Ocean was reached on 3 September 1599, the ships were caught in a storm and lost sight of each other. The "Loyalty" and the "Believe" were driven back in the strait. After more than a year each ship went its own way.

The ''Geloof'' returned to Rotterdam in July 1600 with 36 men surviving of the original 109 crew.

De Cordes ordered his small fleet to wait four weeks for each other on Santa María Island, Chile

Santa María Island is a sparsely inhabited Chilean island located off the coast of Coronel. Santa María Island has been witness to important events in the history of Chile and the world.

History

Santa María Island was called ''Tralca'' or '' ...

, but some ships missed the island. Adams wrote "they brought us sheep and potatoes". From here the story becomes less reliable because of a lack of sources and changes in command. In early November, the "Hope" landed on Mocha Island

Mocha Island ( es, link=no, Isla Mocha ) is a small Chilean island located west of the coast of Arauco Province in the Pacific Ocean. The island is approximately in area, with a small chain of mountains running roughly in north-south direction. ...

where 27 people were killed by the people from Araucania, including Simon de Cordes. (In the account given to Olivier van Noort

Olivier van Noort (1558 – 22 February 1627) was a Dutch merchant captain and pirate and the first Dutchman to circumnavigate the world.Quanchi, ''Historical Dictionary of the Discovery and Exploration of the Pacific Islands'', page 246

Olivier ...

it was said that Simon der Cordes was slain at the Punta de Lavapie, but Adams gives Mocha Island as the scene of his death.) The "Love" hit the island, but went on to Punta de Lavapié near Concepción, Chile

Concepción (; originally: ''Concepción de la Madre Santísima de la Luz'', "Conception of the Blessed Mother of Light") is a city and commune in central Chile, and the geographical and demographic core of the Greater Concepción metropolitan a ...

. A Spanish captain supplied the "Loyalty" and "Hope" with food; the Dutch helped him against the Araucans, who had killed 23 Dutch, including Thomas Adams (according to his brother in his second letter) and Gerrit van Beuningen, who was replaced by Jacob Quaeckernaeck

Jacob Jansz. Quaeckernaeck (or ''Quackernaeck'' or ''Kwakernaak'') (ca. 1543 – 21 September 1606) was a native of Rotterdam and one of the first Dutchmen in Japan, and he was a navigator and later the captain (after the death of the previous ...

.

Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus (; ; English: Erasmus of Rotterdam or Erasmus;''Erasmus'' was his baptismal name, given after St. Erasmus of Formiae. ''Desiderius'' was an adopted additional name, which he used from 1496. The ''Roterodamus'' wa ...

on her stern). The statue was preserved in the Ryuko-in Buddhist

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

temple in Sano City, Tochigi-ken

is a prefecture of Japan located in the Kantō region of Honshu. Tochigi Prefecture has a population of 1,943,886 (1 June 2019) and has a geographic area of 6,408 km2 (2,474 sq mi). Tochigi Prefecture borders Fukushima Prefecture to the nort ...

and moved to the Tokyo National Museum

The or TNM is an art museum in Ueno Park in the Taitō ward of Tokyo, Japan. It is one of the four museums operated by the National Institutes for Cultural Heritage ( :ja:国立文化財機構), is considered the oldest national museum in Japan, ...

in the 1920s. The ''Trouw'' reached Tidore

Tidore ( id, Kota Tidore Kepulauan, lit. "City of Tidore Islands") is a city, island, and archipelago in the Maluku Islands of eastern Indonesia, west of the larger island of Halmahera. Part of North Maluku Province, the city includes the island ...

(Eastern Indonesia

This is a list of some of the regions of Indonesia. Many regions are defined in law or regulations by the central government. At different times of Indonesia's history, the nation has been designated as having regions that do not necessarily corr ...

). The crew were killed by the Portuguese in January 1601.

In fear of the Spaniards, the remaining crews determined to leave the island and sail across the Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

. It was 27 November 1599 when the two ships sailed westward for Japan. On their way, the two ships made landfall in "certain islands" where eight sailors deserted the ships. Later during the voyage, a typhoon

A typhoon is a mature tropical cyclone that develops between 180° and 100°E in the Northern Hemisphere. This region is referred to as the Northwestern Pacific Basin, and is the most active tropical cyclone basin on Earth, accounting for a ...

claimed the ''Hope'' with all hands, in late February 1600.

Arrival in Japan

In April 1600, after more than 19 months at sea, a crew of 23 sick and dying men (out of the 100 who started the voyage) brought the ''Liefde'' to anchor off the island of

In April 1600, after more than 19 months at sea, a crew of 23 sick and dying men (out of the 100 who started the voyage) brought the ''Liefde'' to anchor off the island of Kyūshū

is the third-largest island of Japan's five main islands and the most southerly of the four largest islands ( i.e. excluding Okinawa). In the past, it has been known as , and . The historical regional name referred to Kyushu and its surround ...

, Japan. Its cargo consisted of eleven chests of trade goods: coarse woolen cloth, glass beads, mirrors, and spectacles; and metal tools and weapons: nails, iron, hammers, nineteen bronze cannon; 5,000 cannonballs; 500 muskets, 300 chain-shot

In artillery, chain shot is a type of cannon projectile formed of two sub-calibre balls, or half-balls, chained together. Bar shot is similar, but joined by a solid bar. They were used in the age of sailing ships and black powder cannon to sho ...

, and three chests filled with coats of mail.

When the nine surviving crew members were strong enough to stand, they made landfall on 19 April off Bungo (present-day Usuki, Ōita Prefecture

is a prefecture of Japan located on the island of Kyūshū. Ōita Prefecture has a population of 1,136,245 (1 June 2019) and has a geographic area of 6,340 km2 (2,448 sq mi). Ōita Prefecture borders Fukuoka Prefecture to the northwest, Kumam ...

). They were met by Japanese locals and Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

missionary priests claiming that Adams' ship was a pirate

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

vessel and that the crew should be executed as pirates. The ship was seized and the sickly crew were imprisoned at Osaka Castle

is a Japanese castle in Chūō-ku, Osaka, Japan. The castle is one of Japan's most famous landmarks and it played a major role in the unification of Japan during the sixteenth century of the Azuchi-Momoyama period.

Layout

The main tower ...

on orders by Tokugawa Ieyasu

was the founder and first ''shōgun'' of the Tokugawa Shogunate of Japan, which ruled Japan from 1603 until the Meiji Restoration in 1868. He was one of the three "Great Unifiers" of Japan, along with his former lord Oda Nobunaga and fellow ...

, the ''daimyō

were powerful Japanese magnates, feudal lords who, from the 10th century to the early Meiji era, Meiji period in the middle 19th century, ruled most of Japan from their vast, hereditary land holdings. They were subordinate to the shogun and n ...

'' of Edo and future ''shōgun

, officially , was the title of the military dictators of Japan during most of the period spanning from 1185 to 1868. Nominally appointed by the Emperor, shoguns were usually the de facto rulers of the country, though during part of the Kamakur ...

.'' The nineteen bronze cannon of the ''Liefde'' were unloaded and, according to Spanish accounts, later used at the decisive Battle of Sekigahara

The Battle of Sekigahara (Shinjitai: ; Kyūjitai: , Hepburn romanization: ''Sekigahara no Tatakai'') was a decisive battle on October 21, 1600 (Keichō 5, 15th day of the 9th month) in what is now Gifu prefecture, Japan, at the end of ...

on 21 October 1600.

Adams met Ieyasu in Osaka three times between May and June 1600. He was questioned by Ieyasu, then a guardian of the young son of the '' Taikō'' Toyotomi Hideyoshi

, otherwise known as and , was a Japanese samurai and ''daimyō'' (feudal lord) of the late Sengoku period regarded as the second "Great Unifier" of Japan.Richard Holmes, The World Atlas of Warfare: Military Innovations that Changed the Cour ...

, the ruler who had just died. Adams' knowledge of ships, shipbuilding and nautical smattering of mathematics appealed to Ieyasu.

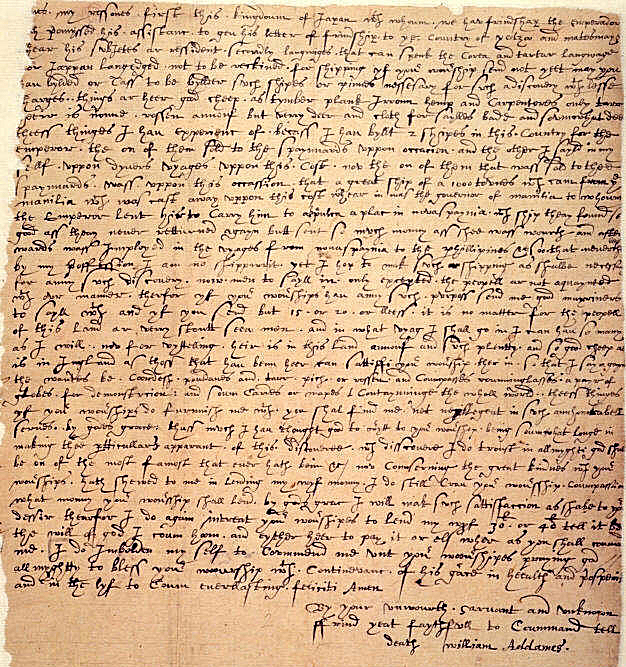

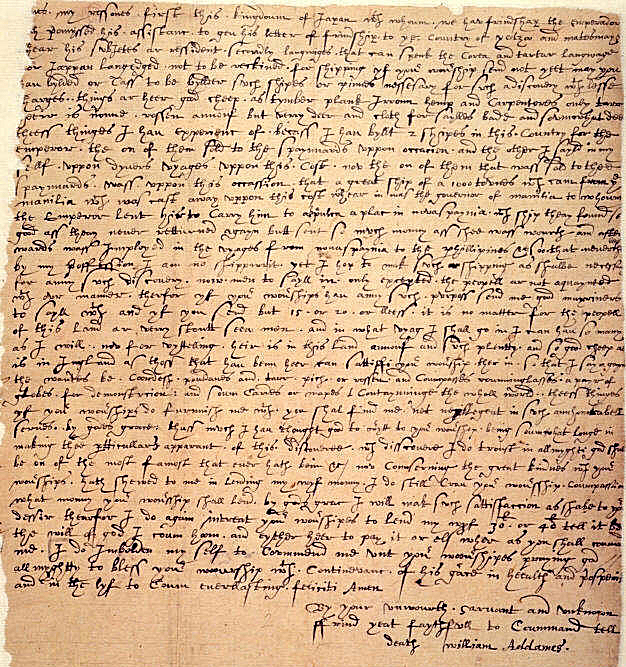

Coming before the king, he viewed me well, and seemed to be wonderfully favourable. He made many signs unto me, some of which I understood, and some I did not. In the end, there came one that could speak Portuguese. By him, the king demanded of me of what land I was, and what moved us to come to his land, being so far off. I showed unto him the name of our country, and that our land had long sought out theAdams wrote that Ieyasu denied the Jesuits' request for execution on the ground that:East Indies The East Indies (or simply the Indies), is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The Indies refers to various lands in the East or the Eastern hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainlands found in and around t ..., and desired friendship with all kings and potentates in way of merchandise, having in our land diverse commodities, which these lands had not… Then he asked whether our country had wars? I answered him yea, with the Spaniards and Portugals, being in peace with all other nations. Further, he asked me, in what I did believe? I said, in God, that made heaven and earth. He asked me diverse other questions of things of religions, and many other things: As what way we came to the country. Having a chart of the whole world, I showed him, through theStrait of Magellan The Strait of Magellan (), also called the Straits of Magellan, is a navigable sea route in southern Chile separating mainland South America to the north and Tierra del Fuego to the south. The strait is considered the most important natural pass .... At which he wondered, and thought me to lie. Thus, from one thing to another, I abode with him till mid-night. (from William Adams' letter to his wife)''Letters Written by the English Residents in Japan, 1611-1623, with Other Documents on the English Trading Settlement in Japan in the Seventeenth Century''

N. Murakami and K. Murakawa, eds., Tokyo: The Sankosha, 1900, pp. 23-24. Spelling has been modernized.

we as yet had not done to him nor to none of his land any harm or damage; therefore against Reason or Justice to put us to death. If our country had wars the one with the other, that was no cause that he should put us to death; with which they were out of heart that their cruel pretence failed them. For which God be forever praised. (William Adams' letter to his wife)Ieyasu ordered the crew to sail the ''Liefde'' from Bungo to Edo where, rotten and beyond repair, she sank.

Japan's first western-style sailing ships

In 1604, Tokugawa ordered Adams and his companions to help Mukai Shōgen, who was commander-in-chief of the navy of Uraga, to build Japan's first Western-style ship. The sailing ship was built at the harbour of Itō on the east coast of theIzu Peninsula

The is a large mountainous peninsula with a deeply indented coastline to the west of Tokyo on the Pacific coast of the island of Honshu, Japan. Formerly known as Izu Province, Izu peninsula is now a part of Shizuoka Prefecture. The peninsul ...

, with carpenters from the harbour supplying the manpower for the construction of an 80-ton vessel. It was used to survey the Japanese coast. The shōgun ordered a larger ship of 120 tons to be built the following year; it was slightly smaller than the ''Liefde'', which was 150 tons. According to Adams, Tokugawa "came aboard to see it, and the sight whereof gave him great content". In 1610, the 120-ton ship (later named ''San Buena Ventura

''San Buena Ventura'' was a 120-ton ship built in Japan under the direction of the English navigator and adventurer William Adams for the ''shōgun'' Tokugawa Ieyasu. The ship was built in 1607, and followed the construction of a smaller 80-to ...

'') was lent to shipwrecked Spanish sailors. They sailed it to New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( es, Virreinato de Nueva España, ), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the Am ...

, accompanied by a mission of twenty-two Japanese led by Tanaka Shōsuke

Tanaka Shōsuke (田中 勝助, also 田中 勝介) was an important Japanese technician and trader in metals from Kyoto during the beginning of the 17th century.

According to Japanese archives (駿府記) he was a representative of the great Osa ...

.

Following the construction, Tokugawa invited Adams to visit his palace whenever he liked and "that always I must come in his presence."

Other survivors of the ''Liefde'' were also rewarded with favours, and were allowed to pursue foreign trade. Most of the survivors left Japan in 1605 with the help of the ''daimyō

were powerful Japanese magnates, feudal lords who, from the 10th century to the early Meiji era, Meiji period in the middle 19th century, ruled most of Japan from their vast, hereditary land holdings. They were subordinate to the shogun and n ...

'' of Hirado

is a city located in Nagasaki Prefecture, Japan. The part historically named Hirado is located on Hirado Island. With recent mergers, the city's boundaries have expanded, and Hirado now occupies parts of the main island of Kyushu. The component ...

. Although Adams did not receive permission to leave Japan until 1613, Melchior van Santvoort and Jan Joosten van Lodensteijn

Jan Joosten van Lodensteyn (or Lodensteijn; 1556–1623), known in Japanese as Yayōsu (耶楊子), was a native of Delft and one of the first Dutchmen in Japan, and the second mate on the Dutch ship ''De Liefde'', which was stranded in Japan in ...

engaged in trade between Japan and Southeast Asia and reportedly made a fortune. Both of them were reported by Dutch traders as being in Ayutthaya Ayutthaya, Ayudhya, or Ayuthia may refer to:

* Ayutthaya Kingdom, a Thai kingdom that existed from 1350 to 1767

** Ayutthaya Historical Park, the ruins of the old capital city of the Ayutthaya Kingdom

* Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya province (locally ...

in early 1613, sailing richly cargoed ''junks

A junk (Chinese: 船, ''chuán'') is a type of Chinese sailing ship with fully battened sails. There are two types of junk in China: northern junk, which developed from Chinese river boats, and southern junk, which developed from Austronesian ...

.''

In 1609 Adams contacted the interim governor of the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, Rodrigo de Vivero y Aberrucia

Rodrigo de Vivero y Aberrucia, 1st Count of Valle de Orizaba ( es, Rodrigo de Vivero y Aberrucia, primer conde del valle de Orizaba) ( Tecamachalco?, New Spain, 1564–1636) was a Spanish noble who served as the 13th governor and captain-gener ...

on behalf of Tokugawa Ieyasu

was the founder and first ''shōgun'' of the Tokugawa Shogunate of Japan, which ruled Japan from 1603 until the Meiji Restoration in 1868. He was one of the three "Great Unifiers" of Japan, along with his former lord Oda Nobunaga and fellow ...

, who wished to establish direct trade contacts with New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( es, Virreinato de Nueva España, ), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the Am ...

. Friendly letters were exchanged, officially starting relations between Japan and New Spain. Adams is also recorded as having chartered Red Seal Ships

were Japanese armed merchant sailing ships bound for Southeast Asia, Southeast Asian ports with red-sealed letters patent issued by the early Tokugawa shogunate in the first half of the 17th century. Between 1600 and 1635, more than 350 Japa ...

during his later travels to Southeast Asia. (The ''Ikoku Tokai Goshuinjō'' has a reference to Miura Anjin receiving a ''shuinjō'', a document bearing a red Shogunal seal authorising the holder to engage in foreign trade, in 1614.)

Samurai status

Taking a liking to Adams, the shōgun appointed him as a diplomatic and trade advisor, bestowing great privileges upon him. Ultimately, Adams became his personal advisor on all things related to Western powers and civilization. After a few years, Adams replaced the Jesuit Padre João Rodrigues as the Shogun's official interpreter. Padre Valentim Carvalho wrote: "After he had learned the language, he had access toIeyasu

was the founder and first '' shōgun'' of the Tokugawa Shogunate of Japan, which ruled Japan from 1603 until the Meiji Restoration in 1868. He was one of the three "Great Unifiers" of Japan, along with his former lord Oda Nobunaga and f ...

and entered the palace at any time"; he also described him as "a great engineer and mathematician".

Adams had a wife Mary Hyn and two children back in England, but Ieyasu forbade the Englishman to leave Japan. He was presented with two swords representing the authority of a

Adams had a wife Mary Hyn and two children back in England, but Ieyasu forbade the Englishman to leave Japan. He was presented with two swords representing the authority of a Samurai

were the hereditary military nobility and officer caste of medieval and early-modern Japan from the late 12th century until their abolition in 1876. They were the well-paid retainers of the '' daimyo'' (the great feudal landholders). They h ...

. The Shogun decreed that William Adams the pilot was dead and that Miura Anjin (三浦按針), a samurai, was born. According to the shōgun, this action "freed" Adams to serve the Shogunate permanently, effectively making Adams' wife in England a widow. (Adams managed to send regular support payments to her after 1613 via the English and Dutch companies.) Adams also was given the title of ''hatamoto

A was a high ranking samurai in the direct service of the Tokugawa shogunate of feudal Japan. While all three of the shogunates in Japanese history had official retainers, in the two preceding ones, they were referred to as ''gokenin.'' However ...

'' (bannerman), a high-prestige position as a direct retainer in the shōgun's court.

Adams was given generous revenues: "For the services that I have done and do daily, being employed in the Emperor's service, the emperor has given me a living" (''Letters''). He was granted a fief in Hemi

Hemi may refer to:

People Surname

* Jack Hemi (1914–1996), New Zealand freezing worker, rugby union and league player, shearer

* Ronald Hemi (1933–2000), New Zealand rugby union player

Given name

* Hemi Bawa, Indian painter and sculptor

* H ...

(Jpn: 逸見) within the boundaries of present-day Yokosuka City

is a city in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan.

, the city has a population of 409,478, and a population density of . The total area is . Yokosuka is the 11th most populous city in the Greater Tokyo Area, and the 12th in the Kantō region.

The city ...

, "with eighty or ninety husbandmen, that be my slaves or servants" (''Letters''). His estate was valued at 250 ''koku

The is a Chinese-based Japanese unit of volume. 1 koku is equivalent to 10 or approximately , or about . It converts, in turn, to 100 shō and 1000 gō. One ''gō'' is the volume of the "rice cup", the plastic measuring cup that is supplied ...

'' (a measure of the yearly income of the land in rice, with one koku defined as the quantity of rice sufficient to feed one person for one year). He finally wrote "God hath provided for me after my great misery" (''Letters''), by which he meant the disaster-ridden voyage that had initially brought him to Japan.

Adams' estate was located next to the harbour of Uraga, the traditional point of entrance to Edo Bay

is a bay located in the southern Kantō region of Japan, and spans the coasts of Tokyo, Kanagawa Prefecture, and Chiba Prefecture. Tokyo Bay is connected to the Pacific Ocean by the Uraga Channel. The Tokyo Bay region is both the most populous ...

. There he was recorded as dealing with the cargoes of foreign ships. John Saris

John Saris () was chief merchant on the first English voyage to Japan, which left London in 1611. He stopped at Yemen, missing India (which he had originally intended to visit) and going on to Java, which had the sole permanent English trading sta ...

related that when he visited Edo in 1613, Adams had resale rights for the cargo of a Spanish ship at anchor in Uraga Bay.

It is rumored that William had a child born in Hirado with another Japanese woman.

Adams' position gave him the means to marry Oyuki (お雪), the adopted daughter of Magome Kageyu. He was a highway official who was in charge of a packhorse exchange on one of the grand imperial roads that led out of Edo (roughly present-day Tokyo). Although Magome was important, Oyuki was not of noble birth, nor high social standing. Adams may have married from affection rather than for social reasons. Adams and Oyuki had a son Joseph and a daughter Susanna. Adams was constantly traveling for work. Initially, he tried to organise an expedition in search of the Arctic

The Arctic ( or ) is a polar regions of Earth, polar region located at the northernmost part of Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean, adjacent seas, and parts of Canada (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut), Danish Realm (Greenla ...

passage that had eluded him previously.

Adams had a high regard for Japan, its people, and its civilisation:

The people of this Land of Japan are good of nature, courteous above measure, and valiant in war: their justice is severely executed without any partiality upon transgressors of the law. They are governed in great civility. I mean, not a land better governed in the world by civil policy. The people be very superstitious in their religion, and are of diverse opinions.William Adams' letter to Bantam, 1612

Establishment of the Dutch East India Company in Japan

In 1604 Ieyasu sent the ''Liefdes captain,

In 1604 Ieyasu sent the ''Liefdes captain, Jacob Quaeckernaeck

Jacob Jansz. Quaeckernaeck (or ''Quackernaeck'' or ''Kwakernaak'') (ca. 1543 – 21 September 1606) was a native of Rotterdam and one of the first Dutchmen in Japan, and he was a navigator and later the captain (after the death of the previous ...

, and the treasurer, Melchior van Santvoort, on a shōgun-licensed Red Seal Ship

were Japanese armed merchant sailing ships bound for Southeast Asian ports with red-sealed letters patent issued by the early Tokugawa shogunate in the first half of the 17th century. Between 1600 and 1635, more than 350 Japanese ships wen ...

to Patani

Patani Darussalam ( Bahasa Malayu Arabic : , also sometimes Patani Raya or Patani Besar, "Greater Patani"; th, ปาตานี) is a historical region in the Malay peninsula. It includes the southern Thai provinces of Pattani, Yala (Ja ...

in Southeast Asia. He ordered them to contact the Dutch East India Company trading factory

A factory, manufacturing plant or a production plant is an industrial facility, often a complex consisting of several buildings filled with machinery, where workers manufacture items or operate machines which process each item into another. T ...

, which had just been established in 1602, in order to bring more western trade to Japan and break the Portuguese monopoly. In 1605, Adams obtained a letter of authorization from Ieyasu formally inviting the Dutch to trade with Japan.

Hampered by conflicts with the Portuguese and limited resources in Asia, the Dutch were not able to send ships to Japan until 1609. Two Dutch ships, commanded by

Hampered by conflicts with the Portuguese and limited resources in Asia, the Dutch were not able to send ships to Japan until 1609. Two Dutch ships, commanded by Jacques Specx

Jacques Specx (; 1585 – 22 July 1652) was a Dutch merchant, who founded the trade on Japan and Korea in 1609. Jacques Specx received the support of William Adams to obtain extensive trading rights from Tokugawa Ieyasu, the ''shōgun'' emeritu ...

, ''De Griffioen'' (the "Griffin", 19 cannons) and ''Roode Leeuw met Pijlen'' (the "Red lion with arrows", 400 tons, 26 cannons), were sent from Holland and reached Japan on 2 July 1609. The men of this Dutch expeditionary fleet established a trading base or "factory" on Hirado Island. Two Dutch envoys, Puyck and van den Broek, were the official bearers of a letter from Prince Maurice of Nassau

Maurice of Orange ( nl, Maurits van Oranje; 14 November 1567 – 23 April 1625) was '' stadtholder'' of all the provinces of the Dutch Republic except for Friesland from 1585 at the earliest until his death in 1625. Before he became Prince ...

to the court of Edo. Adams negotiated on behalf of these emissaries. The Dutch obtained free trading rights throughout Japan and to establish a trading factory there. (By contrast, the Portuguese were allowed to sell their goods only in Nagasaki at fixed, negotiated prices.)

The Hollandes be now settled (in Japan) and I have got them that privilege as the Spaniards and Portingals could never get in this 50 or 60 years in Japan.

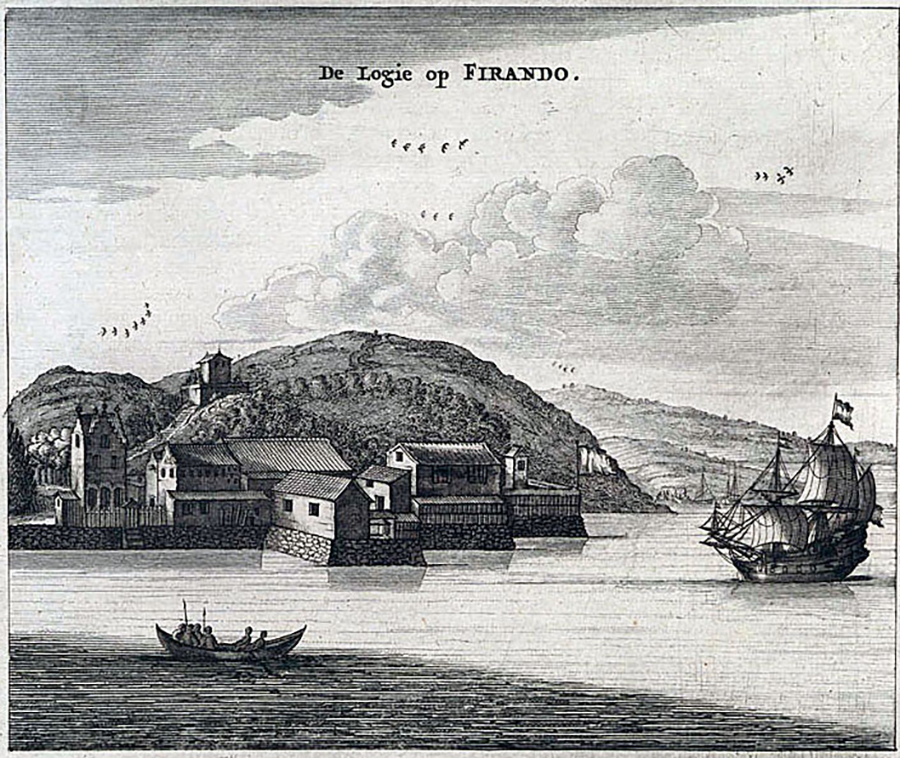

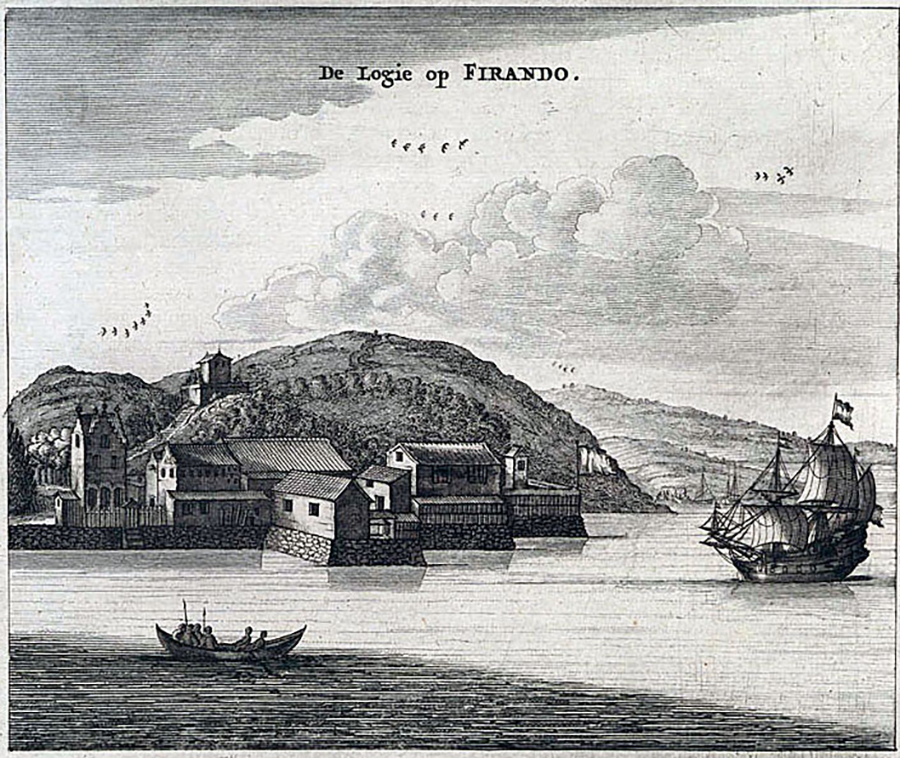

After obtaining this trading right through an edict of Tokugawa Ieyasu on 24 August 1609, the Dutch inaugurated a trading factory in

After obtaining this trading right through an edict of Tokugawa Ieyasu on 24 August 1609, the Dutch inaugurated a trading factory in Hirado

is a city located in Nagasaki Prefecture, Japan. The part historically named Hirado is located on Hirado Island. With recent mergers, the city's boundaries have expanded, and Hirado now occupies parts of the main island of Kyushu. The component ...

on 20 September 1609. The Dutch preserved their "trade pass" (Dutch: ''Handelspas'') in Hirado and then Dejima

, in the 17th century also called Tsukishima ( 築島, "built island"), was an artificial island off Nagasaki, Japan that served as a trading post for the Portuguese (1570–1639) and subsequently the Dutch (1641–1854). For 220 years, it ...

as a guarantee of their trading rights during the following two centuries that they operated in Japan.

Establishment of an English trading factory

In 1611, Adams learned of an English settlement inBanten Sultanate

The Banten Sultanate (كسلطانن بنتن) was a Bantenese Islamic trading kingdom founded in the 16th century and centred in Banten, a port city on the northwest coast of Java; the contemporary English name of both was Bantam. It is said ...

, present-day Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Guine ...

. He wrote asking them to convey news of him to his family and friends in England. He invited them to engage in trade with Japan which "the Hollanders have here an Indies of money."

In 1613, the English captain

In 1613, the English captain John Saris

John Saris () was chief merchant on the first English voyage to Japan, which left London in 1611. He stopped at Yemen, missing India (which he had originally intended to visit) and going on to Java, which had the sole permanent English trading sta ...

arrived at Hirado

is a city located in Nagasaki Prefecture, Japan. The part historically named Hirado is located on Hirado Island. With recent mergers, the city's boundaries have expanded, and Hirado now occupies parts of the main island of Kyushu. The component ...

in the ship ''Clove

Cloves are the aromatic flower buds of a tree in the family Myrtaceae, ''Syzygium aromaticum'' (). They are native to the Maluku Islands (or Moluccas) in Indonesia, and are commonly used as a spice, flavoring or fragrance in consumer products, ...

,'' intending to establish a trading factory for the British East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Southea ...

. The Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( nl, Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the VOC) was a chartered company established on the 20th March 1602 by the States General of the Netherlands amalgamating existing companies into the first joint-stock ...

(VOC) already had a major post at Hirado.

Saris noted Adams' praise of Japan and adoption of Japanese customs:

He persists in giving "admirable and affectionated commendations of Japan. It is generally thought amongst us that he is a naturalized Japaner." (John Saris)In Hirado, Adams refused to stay in English quarters, residing instead with a local Japanese magistrate. The English noted that he wore Japanese dress and spoke Japanese fluently. Adams estimated the cargo of the ''Clove'' was of little value, essentially

broadcloth

Broadcloth is a dense, plain woven cloth, historically made of wool. The defining characteristic of broadcloth is not its finished width but the fact that it was woven much wider (typically 50 to 75% wider than its finished width) and then hea ...

, tin

Tin is a chemical element with the symbol Sn (from la, stannum) and atomic number 50. Tin is a silvery-coloured metal.

Tin is soft enough to be cut with little force and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, t ...

and clove

Cloves are the aromatic flower buds of a tree in the family Myrtaceae, ''Syzygium aromaticum'' (). They are native to the Maluku Islands (or Moluccas) in Indonesia, and are commonly used as a spice, flavoring or fragrance in consumer products, ...

s (acquired in the Spice Islands

A spice is a seed, fruit, root, bark, or other plant substance primarily used for flavoring or coloring food. Spices are distinguished from herbs, which are the leaves, flowers, or stems of plants used for flavoring or as a garnish. Spices ar ...

), saying that "such things as he had brought were not very vendible".

Adams traveled with Saris to Suruga, where they met with Ieyasu at his principal residence in September. The Englishmen continued to

Adams traveled with Saris to Suruga, where they met with Ieyasu at his principal residence in September. The Englishmen continued to Kamakura

is a city in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan.

Kamakura has an estimated population of 172,929 (1 September 2020) and a population density of 4,359 persons per km² over the total area of . Kamakura was designated as a city on 3 November 1939.

Kamak ...

where they visited the noted Kamakura Great Buddha

is a city in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan.

Kamakura has an estimated population of 172,929 (1 September 2020) and a population density of 4,359 persons per km² over the total area of . Kamakura was designated as a city on 3 November 1939.

Kama ...

. (Sailors etched their names of the Daibutsu, made in 1252.) They continued to Edo, where they met Ieyasu's son Hidetada

was the second ''shōgun'' of the Tokugawa dynasty, who ruled from 1605 until his abdication in 1623. He was the third son of Tokugawa Ieyasu, the first ''shōgun'' of the Tokugawa shogunate.

Early life (1579–1593)

Tokugawa Hidetada was bo ...

, who was nominally shōgun, although Ieyasu retained most of the decision-making powers. During that meeting, Hidetada gave Saris two varnish

Varnish is a clear transparent hard protective coating or film. It is not a stain. It usually has a yellowish shade from the manufacturing process and materials used, but it may also be pigmented as desired, and is sold commercially in various ...

ed suits of armour for King James I

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until ...

. As of 2015, one of these suits of armour is housed in the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is separa ...

, the other is on display in the Royal Armouries Museum

The Royal Armouries Museum in Leeds, West Yorkshire, England, is a national museum which displays the National Collection of Arms and Armour. It is part of the Royal Armouries family of museums, with other sites at the Royal Armouries' traditio ...

, Leeds

Leeds () is a city and the administrative centre of the City of Leeds district in West Yorkshire, England. It is built around the River Aire and is in the eastern foothills of the Pennines. It is also the third-largest settlement (by populati ...

. The suits were signed by Iwai Yozaemon of Nanbu. They were part of a series of presentation armours of ancient 15th-century Dō-maru

''Dō-maru'' (胴丸), or "body wrap", was a type of chest armour (''dou or dō'') worn by the samurai class of feudal Japan. ''Dō-maru'' first started to appear in the 11th century as an armour for lesser samurai and retainers. Like the ''ō ...

style.

On their return, the English party visited Tokugawa again. He conferred trading privileges to the English by a Red Seal permit, giving them "free license to abide, buy, sell and barter" in Japan. The English party returned to Hirado on 9 October 1613.

At this meeting, Adams asked for and obtained Tokugawa's authorisation to return to his home country but he finally declined Saris' offer to take him back to England: "I answered him I had spent in this country many years, through which I was poor... nddesirous to get something before my return". His true reasons seem to lie rather with his profound antipathy for Saris: "The reason I would not go with him was for diverse injuries done against me, which were things to me very strange and unlooked for." (William Adams letters)

Adams accepted employment with the newly founded Hirado trading factory, signing a contract on 24November 1613, with the East India Company for the yearly salary of 100 English Pounds. This was more than double the regular salary of 40 Pounds earned by the other factors at Hirado. Adams had a lead role, under

Adams accepted employment with the newly founded Hirado trading factory, signing a contract on 24November 1613, with the East India Company for the yearly salary of 100 English Pounds. This was more than double the regular salary of 40 Pounds earned by the other factors at Hirado. Adams had a lead role, under Richard Cocks

Richard Cocks (1566–1624) was the head of the British East India Company trading post in Hirado, Japan, between 1613 and 1623, from its creation, and lasting to its closure due to bankruptcy.

He was baptised on 20 January 1565 at St Chad's, Se ...

and together with six other compatriots (Tempest Peacock, Richard Wickham, William Eaton, Walter Carwarden, Edmund Sayers and William Nealson), in organising this new English settlement.

Adams had advised Saris against the choice of Hirado, which was small and far away from the major markets in Osaka and Edo; he had recommended selection of Uraga near Edo for a post, but Saris wanted to keep an eye on the Dutch activities.

During the ten-year operations of the East India Company (1613 to 1623), only three English ships after the ''Clove'' brought cargoes directly from London to Japan. They were invariably described as having poor value on the Japanese market. The only trade which helped support the factory was that organised between Japan and South-East Asia; this was chiefly Adams selling Chinese goods for Japanese silver:

Were it not for hope of trade into China, or procuring some benefit from Siam, Pattania and Cochin China, it were no staying in Japon, yet it is certen here is silver enough & may be carried out at pleasure, but then we must bring them commodities to their liking. (Richard Cocks' diary, 1617)

Religious rivalries

The Portuguese and other Catholic religious orders in Japan considered Adams a rival as an English Protestant. After Adams' power had grown, the Jesuits tried to convert him, then offered to secretly bear him away from Japan on a Portuguese ship. The Jesuits' willingness to disobey the order by Ieyasu prohibiting Adams from leaving Japan showed that they feared his growing influence. Catholic priests asserted that he was trying to discredit them. In 1614, Carvalho complained of Adams and other merchants in his annual letter to the Pope, saying that "by false accusationdams and others

A dam is a barrier that stops or restricts the flow of surface water or underground streams. Reservoirs created by dams not only suppress floods but also provide water for activities such as irrigation, tap water, human consumption, Industri ...

have rendered our preachers such objects of suspicion that he eyasufears and readily believes that they are rather spies than sowers of the Holy Faith in his kingdom."

Ieyasu, influenced by Adams' counsels and disturbed by unrest caused by the numerous Catholic converts, expelled the Portuguese Jesuits from Japan in 1614. He demanded that Japanese Catholics abandon their faith. Adams apparently warned Ieyasu against Spanish approaches as well.

Character

After fifteen years spent in Japan, Adams had a difficult time establishing relations with the English arrivals. He initially shunned the company of the newly arrived English sailors in 1613 and could not get on good terms with Saris but Richard Cocks, the head of the Hirado factory, came to appreciate Adams' character and what he had acquired of Japanese self-control. In a letter to the East India Company, Cocks wrote:Participation in Asian trade

Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea route between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic Ocean, along the northern coast of North America via waterways through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The eastern route along the Arct ...

from Asia, which would have greatly reduced the sailing distance between Japan and Europe. Ieyasu asked him if "our countrimen could not find the northwest passage" and Adams contacted the East India Company to organise manpower and supplies. The expedition never got underway.

In his later years, Adams worked for the English East India Company. He made a number of trading voyages to Siam

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 mi ...

in 1616 and Cochinchina

Cochinchina or Cochin-China (, ; vi, Đàng Trong (17th century - 18th century, Việt Nam (1802-1831), Đại Nam (1831-1862), Nam Kỳ (1862-1945); km, កូសាំងស៊ីន, Kosăngsin; french: Cochinchine; ) is a historical exony ...

in 1617 and 1618, sometimes for the Company, sometimes for his own account. He is recorded in Japanese records as the owner of a Red Seal Ship

were Japanese armed merchant sailing ships bound for Southeast Asian ports with red-sealed letters patent issued by the early Tokugawa shogunate in the first half of the 17th century. Between 1600 and 1635, more than 350 Japanese ships wen ...

of 500 tons.

Given the few ships that the company sent from England and the poor trading value of their cargoes (broadcloth, knives, looking glasses, Indian cotton, etc.), Adams was influential in gaining trading certificates from the shōgun to allow the company to participate in the Red Seal system. It made a total of seven junk voyages to Southeast Asia with mixed profit results. Four were led by William Adams as captain. Adams renamed a ship he acquired in 1617 as ''Gift of God;'' he sailed it on his expedition that year to Cochinchina. The expeditions he led are described more fully below.

1614 Siam expedition

In 1614, Adams wanted to organise a trade expedition toSiam

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 mi ...

to bolster the company factory's activities and cash situation. He bought and upgraded a 200-ton Japanese junk for the company, renaming her as ''Sea Adventure''; and hired about 120 Japanese sailors and merchants, as well as several Chinese traders, an Italian and a Castilian (Spanish) trader. The heavily laden ship left in November 1614. The merchants Richard Wickham and Edmund Sayers of the English factory's staff also joined the voyage.

The expedition was to purchase raw silk, Chinese goods, sappan wood, deer skins and ray skins (the latter used for the hilts of Japanese swords). The ship carried £1,250 in silver and £175 of merchandise (Indian cottons, Japanese weapons and lacquerware). The party encountered a typhoon near the Ryukyu Islands

The , also known as the or the , are a chain of Japanese islands that stretch southwest from Kyushu to Taiwan: the Ōsumi, Tokara, Amami, Okinawa, and Sakishima Islands (further divided into the Miyako and Yaeyama Islands), with Yonaguni ...

(modern Okinawa

is a prefecture of Japan. Okinawa Prefecture is the southernmost and westernmost prefecture of Japan, has a population of 1,457,162 (as of 2 February 2020) and a geographic area of 2,281 km2 (880 sq mi).

Naha is the capital and largest city ...

) and had to stop there to repair from 27 December 1614 until May 1615. It returned to Japan in June 1615 without having completed any trade.

1615 Siam expedition

Adams left Hirado in November 1615 for Ayutthaya in Siam on the refitted ''Sea Adventure,'' intent on obtainingsappan wood

''Biancaea sappan'' is a species of flowering tree in the legume family, Fabaceae, that is native to tropical Asia. Common names in English include sappanwood and Indian redwood. Sappanwood is related to brazilwood (''Paubrasilia echinata''), and ...

for resale in Japan. His cargo was chiefly silver (£600) and the Japanese and Indian goods unsold from the previous voyage.

He bought vast quantities of the high-profit products. His partners obtained two ships in Siam in order to transport everything back to Japan. Adams sailed the ''Sea Adventure'' to Japan with 143 tonnes of sappan wood and 3,700 deer skins, returning to Hirado in 47 days. (The return trip took from 5 June and 22 July 1616). Sayers, on a hired Chinese junk, reached Hirado in October 1616 with 44 tons of sappan, wood. The third ship, a Japanese junk, brought 4,560 deer skins to Nagasaki, arriving in June 1617 after the monsoon

A monsoon () is traditionally a seasonal reversing wind accompanied by corresponding changes in precipitation but is now used to describe seasonal changes in atmospheric circulation and precipitation associated with annual latitudinal oscil ...

.

Less than a week before Adams' return, Ieyasu had died. Adams accompanied Cocks and Eaton to court to offer company presents to the new ruler, Hidetada

was the second ''shōgun'' of the Tokugawa dynasty, who ruled from 1605 until his abdication in 1623. He was the third son of Tokugawa Ieyasu, the first ''shōgun'' of the Tokugawa shogunate.

Early life (1579–1593)

Tokugawa Hidetada was bo ...

. Although Ieyasu's death seems to have weakened Adams' political influence, Hidetada agreed to maintain the English trading privileges. He also issued a new Red Seal permit (Shuinjō) to Adams, which allowed him to continue trade activities overseas under the shōgun's protection. His position as ''hatamoto

A was a high ranking samurai in the direct service of the Tokugawa shogunate of feudal Japan. While all three of the shogunates in Japanese history had official retainers, in the two preceding ones, they were referred to as ''gokenin.'' However ...

'' was also renewed.

On this occasion, Adams and Cocks also visited the Japanese Admiral Mukai Shōgen Tadakatsu

Mukai Tadakatsu (1582–1641), more generally known as Mukai Shōgen (Jp:向井将監), was the Admiral of the fleet (Jp:お船手奉行) for the Shōgun Tokugawa Ieyasu during the beginning of the Edo period, in the early 17th century.

Between ...

, who lived near Adams' estate. They discussed plans for a possible invasion of the Catholic Philippines.

1617 Cochinchina expedition

In March 1617, Adams set sail for Cochinchina, having purchased the junk Sayers had brought from Siam and renamed it the ''Gift of God''. He intended to find two English factors, Tempest Peacock and Walter Carwarden, who had departed from Hirado two years before to explore commercial opportunities on the first voyage to South East Asia by the Hirado English Factory. Adams learned in Cochinchina that Peacock had been plied with drink, and killed for his silver. Carwarden, who was waiting in a boat downstream, realised that Peacock had been killed and hastily tried to reach his ship. His boat overturned and he drowned. Adams sold a small cargo of broadcloth, Indian piece goods andivory

Ivory is a hard, white material from the tusks (traditionally from elephants) and teeth of animals, that consists mainly of dentine, one of the physical structures of teeth and tusks. The chemical structure of the teeth and tusks of mammals is ...

in Cochinchina for the modest amount of £351.

1618 Cochinchina expedition

In 1618, Adams is recorded as having organised his last Red Seal trade expedition to Cochinchina andTonkin

Tonkin, also spelled ''Tongkin'', ''Tonquin'' or ''Tongking'', is an exonym referring to the northern region of Vietnam. During the 17th and 18th centuries, this term referred to the domain ''Đàng Ngoài'' under Trịnh lords' control, includi ...

(modern Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

), the last expedition of the English Hirado Factory to Southeast Asia. The ship, a chartered Chinese junk, left Hirado on 11 March 1618 but met with bad weather that forced it to stop at Ōshima in the northern Ryukyu Islands. The ship sailed back to Hirado in May.

Those expeditions to Southeast Asia helped the English factory survive for some time, during that period, sappan wood resold in Japan with a 200% profit, until the factory fell into bankruptcy due to high expenditures.

Death and family legacy

Adams died at Hirado, north ofNagasaki

is the capital and the largest city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hidden Christian Sites in the ...

, on 16 May 1620, at the age of 55. He was buried in Nagasaki, where his grave marker may still be seen. His gravesite is next to a memorial to Saint Francis Xavier

Francis Xavier (born Francisco de Jasso y Azpilicueta; Latin: ''Franciscus Xaverius''; Basque: ''Frantzisko Xabierkoa''; French: ''François Xavier''; Spanish: ''Francisco Javier''; Portuguese: ''Francisco Xavier''; 7 April 15063 December 1 ...

. In his will, he left his townhouse in Edo, his fief in Hemi, and 500 British pounds to be divided evenly between his family in England and his family in Japan. Cocks wrote: "I cannot but be sorrowful for the loss of such a man as Capt William Adams, he having been in such favour with two Emperors of Japan as never any Christian in these part of the world." (Cocks' diary)