William A. F. Browne on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Dr William Alexander Francis Browne (1805–1885) was one of the most significant British asylum doctors of the nineteenth century. At Montrose Asylum (1834–1838) in

Dr William Alexander Francis Browne (1805–1885) was one of the most significant British asylum doctors of the nineteenth century. At Montrose Asylum (1834–1838) in

Dr William Alexander Francis Browne (1805–1885) was one of the most significant British asylum doctors of the nineteenth century. At Montrose Asylum (1834–1838) in

Dr William Alexander Francis Browne (1805–1885) was one of the most significant British asylum doctors of the nineteenth century. At Montrose Asylum (1834–1838) in Angus

Angus may refer to:

Media

* ''Angus'' (film), a 1995 film

* ''Angus Og'' (comics), in the ''Daily Record''

Places Australia

* Angus, New South Wales

Canada

* Angus, Ontario, a community in Essa, Ontario

* East Angus, Quebec

Scotland

* An ...

and at the Crichton Royal in Dumfries (1838–1857), Browne introduced activities for patients including writing, group activity and drama, pioneered early forms of occupational therapy and art therapy, and initiated one of the earliest collections of artistic work by patients in a psychiatric hospital

Psychiatric hospitals, also known as mental health hospitals, behavioral health hospitals, are hospitals or wards specializing in the treatment of severe mental disorders, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, eating disorders, dissociat ...

. In an age which rewarded self-control, Browne encouraged self-expression and may therefore be counted alongside William Tuke

William Tuke (24 March 1732 – 6 December 1822), an English tradesman, philanthropist and Quaker, earned fame for promoting more humane custody and care for people with mental disorders, using what he called gentler methods that came to be ...

, Vincenzo Chiarugi and John Conolly

John Conolly (27 May 1794 – 5 March 1866) was an English psychiatrist. He published the volume ''Indications of Insanity'' in 1830. In 1839, he was appointed resident physician to the Middlesex County Asylum where he introduced the princip ...

as one of the pioneers of the moral treatment

Moral treatment was an approach to mental disorder based on humane psychosocial care or moral discipline that emerged in the 18th century and came to the fore for much of the 19th century, deriving partly from psychiatry or psychology and partly fr ...

of mental illness. Sociologist Andrew Scull

Andrew T. Scull (born 1947) is a British-born sociologist who researches the social history of medicine and the history of psychiatry. He is a distinguished professor of sociology and science studies at University of California, San Diego, and ...

has identified Browne's career with the institutional climax of nineteenth century psychiatry.

In 1857, Browne was appointed Commissioner in Lunacy

The Commissioners in Lunacy or Lunacy Commission were a public body established by the Lunacy Act 1845 to oversee asylums and the welfare of mentally ill people in England and Wales. It succeeded the Metropolitan Commissioners in Lunacy.

Previo ...

for Scotland and, in 1866, he was elected President of the Medico-Psychological Association, now the Royal College of Psychiatrists. He was the father of the eminent psychiatrist James Crichton-Browne

Sir James Crichton-Browne MD FRS FRSE (29 November 1840 – 31 January 1938) was a leading Scottish psychiatrist, neurologist and eugenicist. He is known for studies on the relationship of mental illness to brain injury and for the developmen ...

.

Early life

Browne was the son of an army officer – Lieutenant William Browne of the Cameronian Regiment – who drowned in atroopship

A troopship (also troop ship or troop transport or trooper) is a ship used to carry soldiers, either in peacetime or wartime. Troopships were often drafted from commercial shipping fleets, and were unable land troops directly on shore, typicall ...

disaster (the ''Aurora'' on the Goodwin Sands

Goodwin Sands is a sandbank at the southern end of the North Sea lying off the Deal coast in Kent, England. The area consists of a layer of approximately depth of fine sand resting on an Upper Chalk platform belonging to the same geologi ...

) in December 1805. After this upheaval, Browne was brought up on his maternal grandparents' farm at Polmaise, near Stirling, attending Stirling High School

Stirling High School is a state high school for 11- to 18-year-olds run by Stirling Council in Stirling, Scotland. It is one of seven high schools in the Stirling district, and has approximately 972 pupils. It is located on Torbrex Farm Road, ...

and Edinburgh University

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a Public university, public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted ...

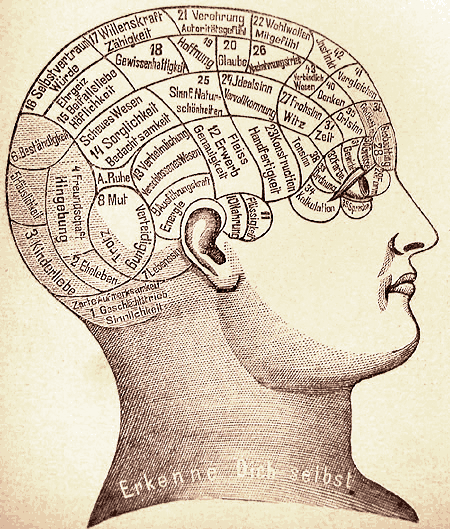

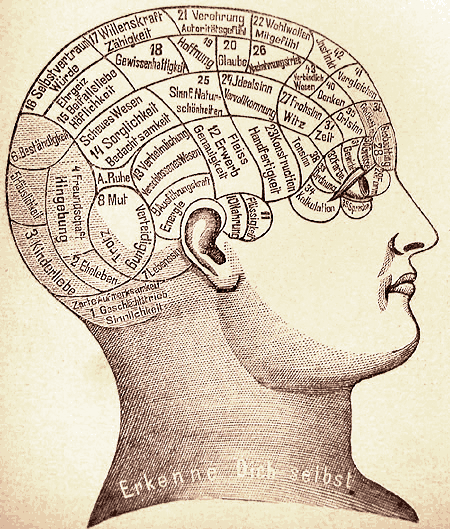

. As a medical student, Browne was fascinated by phrenology and Lamarckian evolution

Lamarckism, also known as Lamarckian inheritance or neo-Lamarckism, is the notion that an organism can pass on to its offspring physical characteristics that the parent organism acquired through use or disuse during its lifetime. It is also calle ...

, joining the Edinburgh Phrenological Society

The Edinburgh Phrenological Society was founded in 1820 by George Combe, an Edinburgh lawyer, with his physician brother Andrew Combe. The Edinburgh Society was the first and foremost phrenology grouping in Great Britain; more than forty ph ...

on 1 April 1824, and taking an active part in the Plinian Society

The Plinian Society was a club at the University of Edinburgh for students interested in natural history. It was founded in 1823. Several of its members went on to have prominent careers, most notably Charles Darwin who announced his first scient ...

with Robert Edmond Grant

Robert Edmond Grant MD FRCPEd FRS FRSE FZS FGS (11 November 1793 – 23 August 1874) was a British anatomist and zoologist.

Life

Grant was born at Argyll Square in Edinburgh (demolished to create Chambers Street), the son of Alexander Gra ...

and Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

in 1826 and the Spring of 1827. Here, Browne presented materialist concepts of the mind as a process of the brain. Browne's amalgamation of phrenology with Lamarckian concepts of evolution anticipated – by some years – the approach of Robert Chambers in his ''Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation

''Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation'' is an 1844 work of speculative natural history and philosophy by Robert Chambers. Published anonymously in England, it brought together various ideas of stellar evolution with the progressive tr ...

'' (1844). The furious arguments which Browne provoked at the Plinian Society

The Plinian Society was a club at the University of Edinburgh for students interested in natural history. It was founded in 1823. Several of its members went on to have prominent careers, most notably Charles Darwin who announced his first scient ...

in 1826/1827 gave ample warning to Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

, then aged 17/18, of the growing tensions between science and religious beliefs.

Student atheism and radicalism

As a medical student, Browne was a Radical and an atheist, welcoming the changes in revolutionary France, and supporting democratic reform to overturn the Church, monarchy, and aristocracy. In addition, Browne was an outspoken advocate of phrenology which George and Andrew Combe had developed into a form of philosophical materialism, asserting that the mind was an outcome of material properties of the brain. Through phrenological meetings, Browne became acquainted with a remarkable group of secular and interdisciplinary thinkers, includingHewett Cottrell Watson

Hewett Cottrell Watson (9 May 1804 – 27 July 1881) was a phrenologist, botanist and evolutionary theorist. He was born in Firbeck, near Rotherham, Yorkshire, and died at Thames Ditton, Surrey.

Biography

Watson was the eldest son of Hollan ...

(an evolutionary thinker and friend of Charles Darwin), William Ballantyne Hodgson

William Ballantyne Hodgson (6 October 1815 – 24 August 1880) was a Scottish educational reformer and political economist.

Life

The son of William Hodgson, a printer, he was born in Edinburgh on 6 October 1815. In 1820 the family were living ...

and Robert Chambers, author of ''Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation

''Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation'' is an 1844 work of speculative natural history and philosophy by Robert Chambers. Published anonymously in England, it brought together various ideas of stellar evolution with the progressive tr ...

''. His interest in natural history led to his membership of the Plinian Society

The Plinian Society was a club at the University of Edinburgh for students interested in natural history. It was founded in 1823. Several of its members went on to have prominent careers, most notably Charles Darwin who announced his first scient ...

, where he took part in vigorous debates concerning phrenology and early evolutionary theories and became one of the five joint presidents of this student club. The leader of the phrenologists, George Combe, toasted Browne for his success in popularising phrenology with other medical students.

Browne presented Plinian papers on various subjects, including plants he had collected, the habits of the cuckoo

Cuckoos are birds in the Cuculidae family, the sole taxon in the order Cuculiformes . The cuckoo family includes the common or European cuckoo, roadrunners, koels, malkohas, couas, coucals and anis. The coucals and anis are sometimes separ ...

, the aurora borealis

An aurora (plural: auroras or aurorae), also commonly known as the polar lights, is a natural light display in Earth's sky, predominantly seen in high-latitude regions (around the Arctic and Antarctic). Auroras display dynamic patterns of bri ...

, and ghosts. On 21 November 1826, he proposed Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

for membership of the Plinian Society. On the same evening, Browne announced a paper which he presented in December 1826, contesting Charles Bell's ''Anatomy and Philosophy of Expression''. Bell, the son of a clergyman and an enormously influential neurologist, claimed, in line with the principles of natural theology, that the Creator had endowed human beings with a unique facial musculature which enabled them to express their higher moral nature in a way which was impossible in animals. Bell's aphorism on the subject was:

Browne argued that these anatomical differences were lacking and that such essential differences between human beings and animals did not exist. Forty-five years later, Darwin pursued an identical argument in his ''The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals

''The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals'' is Charles Darwin's third major work of evolutionary theory, following ''On the Origin of Species'' (1859) and '' The Descent of Man'' (1871). Initially intended as a chapter in ''The Desce ...

'' (1872), confiding in Alfred Russel Wallace that one of his main purposes was to discredit the slippery rhetoric of Sir Charles Bell.

Later, at a Plinian meeting on 27 March 1827, Browne followed Darwin's paper on marine invertebrate

Marine invertebrates are the invertebrates that live in marine habitats. Invertebrate is a blanket term that includes all animals apart from the vertebrate members of the chordate phylum. Invertebrates lack a vertebral column, and some hav ...

s and Dr Robert Edmund Grant

Robert Edmond Grant MD FRCPEd FRS FRSE FZS FGS (11 November 1793 – 23 August 1874) was a British anatomist and zoologist.

Life

Grant was born at Argyll Square in Edinburgh (demolished to create Chambers Street), the son of Alexander Gra ...

's exposition on sea-mats with a presentation that mind and consciousness were simply aspects of brain activity. This programme of three papers presented an ascending view of life's complexities from the marine invertebrates beloved of Grant to the ultimate mysteries of human consciousness, all on a scientific platform of evolutionary development. In addition, Browne appeared to present a view of the world which was politically and morally at odds with the opinions of the educational establishment. A furious debate ensued, and subsequently someone (probably the crypto-Lamarckian Robert Jameson

Robert Jameson

Robert Jameson FRS FRSE (11 July 1774 – 19 April 1854) was a Scottish naturalist and mineralogist.

As Regius Professor of Natural History at the University of Edinburgh for fifty years, developing his predecessor John ...

, Regius Professor of Natural History) took the extraordinary step of deleting the minutes of this heretical part of the discussion. The deletion, however, was incomplete and has allowed a final restoration of the discussion. The extreme impact of these events is indicated by the fact that a friend of Browne's – John Coldstream – developed an emotional disturbance which his doctor attributed to his being

After graduating at Edinburgh, Browne travelled to Paris and studied psychiatry

Psychiatry is the specialty (medicine), medical specialty devoted to the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of mental disorders. These include various maladaptations related to mood, behaviour, cognition, and perceptions. See glossary of psych ...

with Jean-Étienne Dominique Esquirol

Jean-Étienne Dominique Esquirol (3 February 1772 – 12 December 1840) was a French psychiatrist.

Early life and education

Born and raised in Toulouse, Esquirol completed his education at Montpellier. He came to Paris in 1799 where he worked ...

at the Salpêtrière.

Early psychiatric career

Browne became a physician atStirling

Stirling (; sco, Stirlin; gd, Sruighlea ) is a city in central Scotland, northeast of Glasgow and north-west of Edinburgh. The market town, surrounded by rich farmland, grew up connecting the royal citadel, the medieval old town with its me ...

in 1830, and gave lectures on physiology

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a sub-discipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out the chemical ...

and zoology

Zoology ()The pronunciation of zoology as is usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon. is the branch of biology that studies the animal kingdom, including the structure, embryology, evolution, classification, habits, and ...

at the Edinburgh Association which was formed in 1832 by the town's tradesmen. He also travelled in continental Europe. In 1832–1834, Browne published a lengthy paper in the ''Phrenological Journal'' concerning the relationship of language to mental disorder and in 1834 he was appointed superintendent of Montrose Lunatic Asylum. On 24 June 1834, Browne married Magdalene Balfour, from one of Scotland's foremost scientific families and sister of John Hutton Balfour

John Hutton Balfour (15 September 1808 – 11 February 1884) was a Scottish botanist. Balfour became a Professor of Botany, first at the University of Glasgow in 1841, moving to the University of Edinburgh and also becoming the 7th Regius Kee ...

(1808–1884), and they were to have eight children, the second of whom was James Crichton-Browne

Sir James Crichton-Browne MD FRS FRSE (29 November 1840 – 31 January 1938) was a leading Scottish psychiatrist, neurologist and eugenicist. He is known for studies on the relationship of mental illness to brain injury and for the developmen ...

(1840–1938), an eminent psychiatrist of the later Victorian period. Browne gave frequent lectures on the reform of mental institutions, often expressing himself in surprisingly political/reformist terms – like a sociological visionary. In 1837, five lectures he had delivered before the Managers of Montrose Lunatic Asylum were published under the title ''What Asylums Were, Are, and Ought To Be'', setting out his ideas of the ideal asylum of the future and, in many ways, Browne sought to arrest – or even to reverse – the social consequences of the widespread industrialisation which had disrupted the Scottish culture

The culture of Scotland refers to the patterns of human activity and symbolism associated with Scotland and the Scottish people. The Scottish flag is blue with a white saltire, and represents the cross of Saint Andrew.

Scots law

Scotland retain ...

of his childhood.

In this enormously influential book, Browne agreed with the contemporary perception that insanity was associated with the social upheavals consequent upon the industrial revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

– and claimed that insanity was increasing because

In some ways, Browne anticipated the French psychiatrist Bénédict Morel whose clinical theories of degeneration were published in his 1857 masterpiece ''Treatise on Degeneration''. Browne – rather surprisingly – supported the idea that insanity was most prevalent amongst the highest rank of society and he concluded that "the agricultural population..... is to a great degree exempt from insanity". He speculated that insanity was common in America because

He also suggested that the higher incidence of mental illness amongst women was the result of inequalities and poorer education. On the basis of his studies of inmates of his hospital, he asserted that those canonised in the past as saints for their hyperactive organ of veneration would now be categorised as insane.

Crichton Royal: Moral Treatment and Therapeutic Approaches

Browne was a passionate advocate of themoral treatment

Moral treatment was an approach to mental disorder based on humane psychosocial care or moral discipline that emerged in the 18th century and came to the fore for much of the 19th century, deriving partly from psychiatry or psychology and partly fr ...

of the insane and he hated any suggestion of prejudice against the mentally ill.

In 1838 the wealthy philanthropist Elizabeth Crichton persuaded Browne to accept the position of physician superintendent of her newly constructed Crichton Royal Hospital in Dumfries. Here he encouraged his patients with writing, art and drama and a host of other activities, long anticipating the clinical approaches of occupational therapy and art therapy. He made regular records of his patients' dreams, and of their social activities and groupings. Elizabeth Crichton would have monthly meetings with him. In 1855, the Crichton was visited by the celebrated American reformer Dorothea Dix

Dorothea Lynde Dix (April 4, 1802July 17, 1887) was an American advocate on behalf of the indigent mentally ill who, through a vigorous and sustained program of lobbying state legislatures and the United States Congress, created the first gen ...

and she seems to have struck up a positive relationship with Magdalene Browne, taking an interest in her traditional Scottish cuisine, before moving on to her Edinburgh friends, Mr and Mrs Robert Chambers. Browne remained at the Crichton until 1857 when his outstanding reputation resulted in his appointment as the first Medical Commissioner to the Scottish asylums. In 1866, he was elected President of the Medico-Psychological Association

The Royal College of Psychiatrists is the main professional organisation of psychiatrists in the United Kingdom, and is responsible for representing psychiatrists, for psychiatric research and for providing public information about mental health ...

, and he used his Presidential Address as an opportunity to spell out (at considerable length) his concepts of medical psychology.

In 1870, while visiting asylums in East Lothian, Browne was involved in a road accident which resulted in his resignation as Commissioner in Lunacy, and, later, in increasing problems with his eyesight. He may have been suffering some ophthalmic problems, probably glaucoma

Glaucoma is a group of eye diseases that result in damage to the optic nerve (or retina) and cause vision loss. The most common type is open-angle (wide angle, chronic simple) glaucoma, in which the drainage angle for fluid within the eye rem ...

, from years earlier. Browne retired to his home in Dumfries and worked on a series of medico-literary projects, including the ''Religio Psycho-Medici'' (1877) in which he re-explored the territories of psychopathology and the spiritual outlook.

Towards the end of his career, Browne returned to the relationships of language, psychosis and brain injury in his 1872 paper ''Impairment of Language, the Result of Cerebral Disease'' published in the ''West Riding Lunatic Asylum Medical Reports'', edited by his son James Crichton-Browne

Sir James Crichton-Browne MD FRS FRSE (29 November 1840 – 31 January 1938) was a leading Scottish psychiatrist, neurologist and eugenicist. He is known for studies on the relationship of mental illness to brain injury and for the developmen ...

. At this time, Crichton-Browne was concluding a lengthy correspondence with Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

during the preparation and publication of ''The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals

''The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals'' is Charles Darwin's third major work of evolutionary theory, following ''On the Origin of Species'' (1859) and '' The Descent of Man'' (1871). Initially intended as a chapter in ''The Desce ...

''.

In 1839, Browne had initiated one of the first collections of art by mental patients in institutions, gathering a large amount of work which he had bound into three volumes, in many ways a forerunner to Hans Prinzhorn

Hans Prinzhorn (6 June 1886 – 14 June 1933) was a German psychiatrist and art historian.

Born in Hemer, Westphalia, he studied art history and philosophy at the University of Vienna, receiving his doctorate in 1908. He then went to England t ...

's '' Artistry of the Mentally Ill'' and the academic study of outsider art

Outsider art is art made by self-taught or supposedly naïve artists with typically little or no contact with the conventions of the art worlds. In many cases, their work is discovered only after their deaths. Often, outsider art illustrate ...

( art brut).Park, Maureen (2010) ''Art in Madness: Dr W A F Browne's Collection of Patient Art at Crichton Royal Institution, Dumfries'' Dumfries and Galloway Health Board. A paper by Browne on ''Mad Artists'' was published in 1880 in the ''Journal of Psychological Medicine and Mental Pathology'', setting out his views on mental illness and the effect it had on established artists. Browne's last years were clouded by the death of his wife in January 1882 and by his increasing blindness; but he lived to hear of his son's achievements in medical psychology rewarded by his election – in 1883 – as a Fellow of the Royal Society.

W.A.F. Browne's legacy

Universally regarded as a superb asylum superintendent and as a distinguished President of theMedico-Psychological Association

The Royal College of Psychiatrists is the main professional organisation of psychiatrists in the United Kingdom, and is responsible for representing psychiatrists, for psychiatric research and for providing public information about mental health ...

(1866), Browne's reputation rested substantially on his achievements as an asylum reformer – with acute responsiveness to the psychological lives of his patients. Browne's early writings on asylum management – including his celebrated ''What Asylums Were, Are and Ought To Be'' – brought him international recognition, with honorary doctorates from Heidelberg and Wisconsin. He was also elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

Browne is now considered as an important influence – along with Robert Grant – on the youthful Charles Darwin as a medical student in Edinburgh in 1826/1827. In December 1826, Browne delivered an inflammatory harangue to the Plinian Society

The Plinian Society was a club at the University of Edinburgh for students interested in natural history. It was founded in 1823. Several of its members went on to have prominent careers, most notably Charles Darwin who announced his first scient ...

concerning emotional expression – contesting the doctrines of Charles Bell. On 27 March 1827, Browne spelled out the full implications of a materialistic theory of the mind at the Plinian Society – and the 18-year-old Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

was there to hear on both occasions. In this way, Browne was a pivotal figure in the mutual engagement of psychiatry and evolutionary theory. Browne's son, James Crichton Browne, greatly extended his work in psychiatry and medical psychology. In his correspondence with Crichton-Browne, Charles Darwin remarked – during the preparation of ''The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals

''The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals'' is Charles Darwin's third major work of evolutionary theory, following ''On the Origin of Species'' (1859) and '' The Descent of Man'' (1871). Initially intended as a chapter in ''The Desce ...

'' (1872) – that it should be regarded as authored "by Darwin ''and'' Browne".

Notes

References

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Browne, William A. F. 1805 births 1885 deaths Scottish psychiatrists People educated at Stirling High School Alumni of the University of Edinburgh Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Heads of psychiatric hospitals History of mental health in the United Kingdom Art therapists Lamarckism Phrenologists Charles Darwin British psychiatrists Mental health activists People associated with Angus, Scotland People associated with Dumfries and Galloway