Wilkes Exploring Expedition on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The United States Exploring Expedition of 1838–1842 was an exploring and surveying expedition of the

The United States Exploring Expedition of 1838–1842 was an exploring and surveying expedition of the

The Squadron did not leave Rio de Janeiro until January 6, 1839, arriving at the mouth of the Río Negro on January 25. On February 19, the squadron joined the ''Relief'', ''Flying Fish'', and ''Sea Gull'' in Orange Harbor,

The Squadron did not leave Rio de Janeiro until January 6, 1839, arriving at the mouth of the Río Negro on January 25. On February 19, the squadron joined the ''Relief'', ''Flying Fish'', and ''Sea Gull'' in Orange Harbor,  The expedition then visited

The expedition then visited

On August 9, after three months of surveying, the squadron met off

On August 9, after three months of surveying, the squadron met off

The United States Exploring Expedition of 1838–1842 was an exploring and surveying expedition of the

The United States Exploring Expedition of 1838–1842 was an exploring and surveying expedition of the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

and surrounding lands conducted by the United States. The original appointed commanding officer was Commodore

Commodore may refer to:

Ranks

* Commodore (rank), a naval rank

** Commodore (Royal Navy), in the United Kingdom

** Commodore (United States)

** Commodore (Canada)

** Commodore (Finland)

** Commodore (Germany) or ''Kommodore''

* Air commodore, a ...

Thomas ap Catesby Jones

Thomas ''ap'' Catesby Jones (24 April 1790 – 30 May 1858) was a U.S. Navy commissioned officer during the War of 1812 and the Mexican–American War.

Early life and education

Thomas ap Catesby Jones was born on 24 April 1790 in Westmor ...

. Funding for the original expedition was requested by President John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States S ...

in 1828; however, Congress would not implement funding until eight years later. In May 1836, the oceanic exploration voyage was finally authorized by Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of a ...

and created by President Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

.

The expedition is sometimes called the U.S. Ex. Ex. for short, or the Wilkes Expedition in honor of its next appointed commanding officer, United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

Lieutenant Charles Wilkes

Charles Wilkes (April 3, 1798 – February 8, 1877) was an American naval officer, ship's captain, and explorer. He led the United States Exploring Expedition (1838–1842).

During the American Civil War (1861–1865), he commanded ' during the ...

. The expedition was of major importance to the growth of science in the United States, in particular the then-young field of oceanography

Oceanography (), also known as oceanology and ocean science, is the scientific study of the oceans. It is an Earth science, which covers a wide range of topics, including ecosystem dynamics; ocean currents, waves, and geophysical fluid dynamic ...

. During the event, armed conflict between Pacific islanders and the expedition was common and dozens of natives were killed in action, as well as a few Americans.

Preparations

Through the lobbying efforts ofJeremiah N. Reynolds

Jeremiah N. Reynolds (fall 1799 – August 25, 1858), also known as J. N. Reynolds, was an American newspaper editor, lecturer, explorer and author who became an influential advocate for scientific expeditions. His lectures on the possibility of a ...

, the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the Lower house, lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the United States Senate, Senate being ...

passed a resolution on May 21, 1828, requesting President John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States S ...

to send a ship to explore the Pacific. Adams was keen on the resolution and ordered his Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the se ...

to ready a ship, the ''Peacock''. The House voted an appropriation in December but the bill stalled in the US Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and powe ...

in February 1829. Then, under President Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

, Congress passed legislation in 1836 approving the exploration mission. Again, the effort stalled under Secretary of the Navy Mahlon Dickerson

Mahlon Dickerson (April 17, 1770 – October 5, 1853) was a justice of the Supreme Court of New Jersey, the seventh governor of New Jersey, United States Senator from New Jersey, the 10th United States Secretary of the Navy and a United States ...

until President Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; nl, Maarten van Buren; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was an American lawyer and statesman who served as the eighth president of the United States from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party, he ...

assumed office and pushed the effort forward.

Originally, the expedition was under the command Commodore Jones, but he resigned in November 1837, frustrated with all of the procrastination. Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

Joel Roberts Poinsett

Joel Roberts Poinsett (March 2, 1779December 12, 1851) was an American physician, diplomat and botanist. He was the first U.S. agent in South America, a member of the South Carolina legislature and the United States House of Representatives, the ...

, in April 1838, then assigned command to Wilkes, after more senior officers refused the command. Wilkes had a reputation for hydrography

Hydrography is the branch of applied sciences which deals with the measurement and description of the physical features of oceans, seas, coastal areas, lakes and rivers, as well as with the prediction of their change over time, for the primary p ...

, geodesy

Geodesy ( ) is the Earth science of accurately measuring and understanding Earth's figure (geometric shape and size), orientation in space, and gravity. The field also incorporates studies of how these properties change over time and equivale ...

, and magnetism

Magnetism is the class of physical attributes that are mediated by a magnetic field, which refers to the capacity to induce attractive and repulsive phenomena in other entities. Electric currents and the magnetic moments of elementary particles ...

. Additionally, Wilkes had received mathematics training from Nathaniel Bowditch

Nathaniel Bowditch (March 26, 1773 – March 16, 1838) was an early American mathematician remembered for his work on ocean navigation. He is often credited as the founder of modern maritime navigation; his book '' The New American Practical Navi ...

, triangulation

In trigonometry and geometry, triangulation is the process of determining the location of a point by forming triangles to the point from known points.

Applications

In surveying

Specifically in surveying, triangulation involves only angle me ...

methods from Ferdinand Hassler

Ferdinand Rudolph Hassler (October 6, 1770 – November 20, 1843) was a Swiss-American surveyor who is considered the forefather of both the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the National Institute of Standards and Techn ...

, and geomagnetism from James Renwick.

Personnel included naturalists, botanist

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek wo ...

s, a mineralogist

Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical (including optical) properties of minerals and mineralized artifacts. Specific studies within mineralogy include the proces ...

, a taxidermist

Taxidermy is the art of preserving an animal's body via mounting (over an armature) or stuffing, for the purpose of display or study. Animals are often, but not always, portrayed in a lifelike state. The word ''taxidermy'' describes the proce ...

, and a philologist

Philology () is the study of language in oral and written historical sources; it is the intersection of textual criticism, literary criticism, history, and linguistics (with especially strong ties to etymology). Philology is also defined as th ...

. They were carried aboard the sloops-of-war

In the 18th century and most of the 19th, a sloop-of-war in the Royal Navy was a warship with a single gun deck that carried up to eighteen guns. The rating system covered all vessels with 20 guns and above; thus, the term ''sloop-of-war'' enc ...

(780 tons), and (650 tons), the brig

A brig is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: two masts which are both square rig, square-rigged. Brigs originated in the second half of the 18th century and were a common type of smaller merchant vessel or warship from then until the ...

(230 tons), the full-rigged ship

A full-rigged ship or fully rigged ship is a sailing vessel's sail plan with three or more masts, all of them square-rigged. A full-rigged ship is said to have a ship rig or be ship-rigged. Such vessels also have each mast stepped in three se ...

''Relief'', which served as a store-ship, and two schooner

A schooner () is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than the mainmast. A common variant, the topsail schoon ...

s, ''Sea Gull'' (110 tons) and (96 tons), which served as tenders.

On the afternoon of August 18, 1838, the vessels weighed anchor and set to sea under full sail. By 0730 the next morning, they had passed the lightship off Willoughby Spit

Willoughby Spit is a peninsula of land in the independent city of Norfolk, Virginia in the United States. It is bordered by water on three sides: the Chesapeake Bay to the north, Hampton Roads to the west, and Willoughby Bay to the south.

Hist ...

and discharged the pilot

An aircraft pilot or aviator is a person who controls the flight of an aircraft by operating its directional flight controls. Some other aircrew members, such as navigators or flight engineers, are also considered aviators, because they a ...

. The fleet then headed to Madeira

)

, anthem = ( en, "Anthem of the Autonomous Region of Madeira")

, song_type = Regional anthem

, image_map=EU-Portugal_with_Madeira_circled.svg

, map_alt=Location of Madeira

, map_caption=Location of Madeira

, subdivision_type=Sovereign st ...

, taking advantage of the prevailing winds.

Coincidentally, Commodore

Commodore may refer to:

Ranks

* Commodore (rank), a naval rank

** Commodore (Royal Navy), in the United Kingdom

** Commodore (United States)

** Commodore (Canada)

** Commodore (Finland)

** Commodore (Germany) or ''Kommodore''

* Air commodore, a ...

George C. Read

George Campbell Read (January 9, 1788August 22, 1862) was a United States Naval officer who served on Old Ironsides during the War of 1812 and commanded vessels in actions off the Barbary Coast and India. Read eventually rose to the rank of r ...

in command of the East India Squadron

The East India Squadron, or East Indies Squadron, was a squadron of American ships which existed in the nineteenth century, it focused on protecting American interests in the Far East while the Pacific Squadron concentrated on the western coast ...

aboard the flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the fi ...

frigate USS ''Columbia'', together with the frigate USS ''John Adams'', were at the time in the process of circumnavigating the globe when the ships paused for the second Sumatran punitive expedition, which required no detour.

Ships and personnel

The expedition consisted of nearly 350 men, many of whom were not assigned to any specific vessel. Others served on more than one vessel.Ships

* –sloop-of-war

In the 18th century and most of the 19th, a sloop-of-war in the Royal Navy was a warship with a single gun deck that carried up to eighteen guns. The rating system covered all vessels with 20 guns and above; thus, the term ''sloop-of-war'' enc ...

, 780 tons, 18 guns, flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the fi ...

* – sloop-of-war, 650 tons, 22 guns

* – full-rigged ship

A full-rigged ship or fully rigged ship is a sailing vessel's sail plan with three or more masts, all of them square-rigged. A full-rigged ship is said to have a ship rig or be ship-rigged. Such vessels also have each mast stepped in three se ...

, 468 tons, 7 guns

* – brig

A brig is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: two masts which are both square rig, square-rigged. Brigs originated in the second half of the 18th century and were a common type of smaller merchant vessel or warship from then until the ...

, 230 tons, 10 guns

* – schooner

A schooner () is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than the mainmast. A common variant, the topsail schoon ...

, 110 tons, 2 guns

* – schooner, 96 tons, 2 guns

* – brig, 250 tons, 2 guns

Command

*Charles Wilkes

Charles Wilkes (April 3, 1798 – February 8, 1877) was an American naval officer, ship's captain, and explorer. He led the United States Exploring Expedition (1838–1842).

During the American Civil War (1861–1865), he commanded ' during the ...

– Expedition commander and commandant of ''Vincennes''

* Cadwalader Ringgold

Cadwalader Ringgold (August 20, 1802 – April 29, 1867) was an officer in the United States Navy who served in the United States Exploring Expedition, later headed an expedition to the Northwest and, after initially retiring, returned to service ...

– Lieutenant commandant of ''Porpoise''

* Andrew K. Long – Lieutenant commandant of ''Relief''

* William L. Hudson

Captain William Levereth Hudson, USN (11 May 1794 – 15 October 1862) was a United States Navy officer in the first half of the 19th century.

Career

Hudson was born 11 May 1794 in Brooklyn. His first service afloat was in the Mediterranean Squa ...

– Commandant

Commandant ( or ) is a title often given to the officer in charge of a military (or other uniformed service) training establishment or academy. This usage is common in English-speaking nations. In some countries it may be a military or police ran ...

of ''Peacock''

* Samuel R. Knox – Commandant of ''Flying Fish''

* James W. E. Reid – Commandant of ''Sea Gull''

Naval officers

*James Alden

James Alden Jr. (March 31, 1810 – February 6, 1877) was a rear admiral in the United States Navy. In the Mexican–American War he participated in the captures of Veracruz, Tuxpan, and Tabasco. Fighting on the Union side in the Civil War, he took ...

– Lieutenant

* Daniel Ammen

Daniel Ammen (May 15, 1820 – July 11, 1898) was a United States Navy, U.S. naval officer during the American Civil War and the Reconstruction era of the United States, postbellum period, as well as a prolific author. His last assignment in t ...

- Passed midshipman

* Thomas A. Budd

Thomas A. Budd (April 28, 1818 – March 22, 1862) was a United States Naval officer.

Budd entered the navy as a midshipman in 1829, was promoted to passed midshipman in 1835, and earned the rank of lieutenant in 1841.Delgado, James P. To Cal ...

– Lieutenant and cartographer

Cartography (; from grc, χάρτης , "papyrus, sheet of paper, map"; and , "write") is the study and practice of making and using maps. Combining science, aesthetics and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality (or an im ...

* Simon F. Blunt

Simon Fraser Blunt (August 1, 1818 – April 27, 1854) was a member of the Wilkes Expedition, Cartographer of San Francisco Bay and was Captain of the SS Winfield Scott when it shipwrecked off Anacapa Island in 1853. Two geographic features, Bl ...

– Passed midshipman

A passed midshipman, sometimes called as "midshipman, passed", is a term used historically in the 19th century to describe a midshipman who had passed the lieutenant's exam and was eligible for promotion to lieutenant as soon as there was a vacan ...

* Augustus Case

Augustus Ludlow Case (February 3, 1812 – February 16, 1893) was a rear admiral in the United States Navy who served during the American Civil War.

Biography

Born in Newburgh, New York, Case was appointed midshipman in 1828.

He participated ...

– Lieutenant

* George Colvocoresses

George Musalas "Colvos" Colvocoresses (October 22, 1816 – June 3, 1872) was a Greek-American United States Navy, Navy officer who commanded the during the American Civil War. From 1838 up until 1842, he took part in the United States Exploring ...

– Midshipman

A midshipman is an officer of the lowest rank, in the Royal Navy, United States Navy, and many Commonwealth navies. Commonwealth countries which use the rank include Canada (Naval Cadet), Australia, Bangladesh, Namibia, New Zealand, South Afr ...

* Edwin De Haven

Edwin Jesse DeHaven (May 7, 1816May 1, 1865) was a United States Navy officer and explorer of the first half of the 19th century who was best known for his command of the First Grinnell expedition in 1850, which was directed to ascertain what had ...

– Acting Master

* Henry Eld

Henry Eld (June 2, 1814—March 12, 1850) was a United States Navy officer, geographer, and Antarctic explorer.

Biography

Eld was born in Cedar Hill, New Haven, Connecticut, on June 2, 1814, and lived in the area now known as View Street, but whe ...

– Midshipman

* George F. Emmons

George Foster Emmons (August 23, 1811 – July 23, 1884) was a rear admiral of the United States Navy, who served in the early to mid 19th century.

Biography

He was born in Clarendon, Vermont on August 23, 1811. Emmons began his distinguishe ...

– Lieutenant

* Charles Guillou

Charles Fleury Bien-aimé Guilloû (July 14, 1813 – January 2, 1899) was an American military physician. He served on a major exploring expedition that included both scientific discoveries and controversy, and two historic diplomatic missions. ...

– Assistant surgeon

* William L. Maury – Lieutenant

* William Reynolds – Passed midshipman

* Richard R. Waldron – Purser

A purser is the person on a ship principally responsible for the handling of money on board. On modern merchant ships, the purser is the officer responsible for all administration (including the ship's cargo and passenger manifests) and supply. ...

* Thomas W. Waldron – Captain's clerk

A captain's clerk was a rating, now obsolete, in the Royal Navy and the United States Navy for a person employed by the captain to keep his records, correspondence, and accounts. The regulations of the Royal Navy demanded that a purser serve at ...

Scientific corps

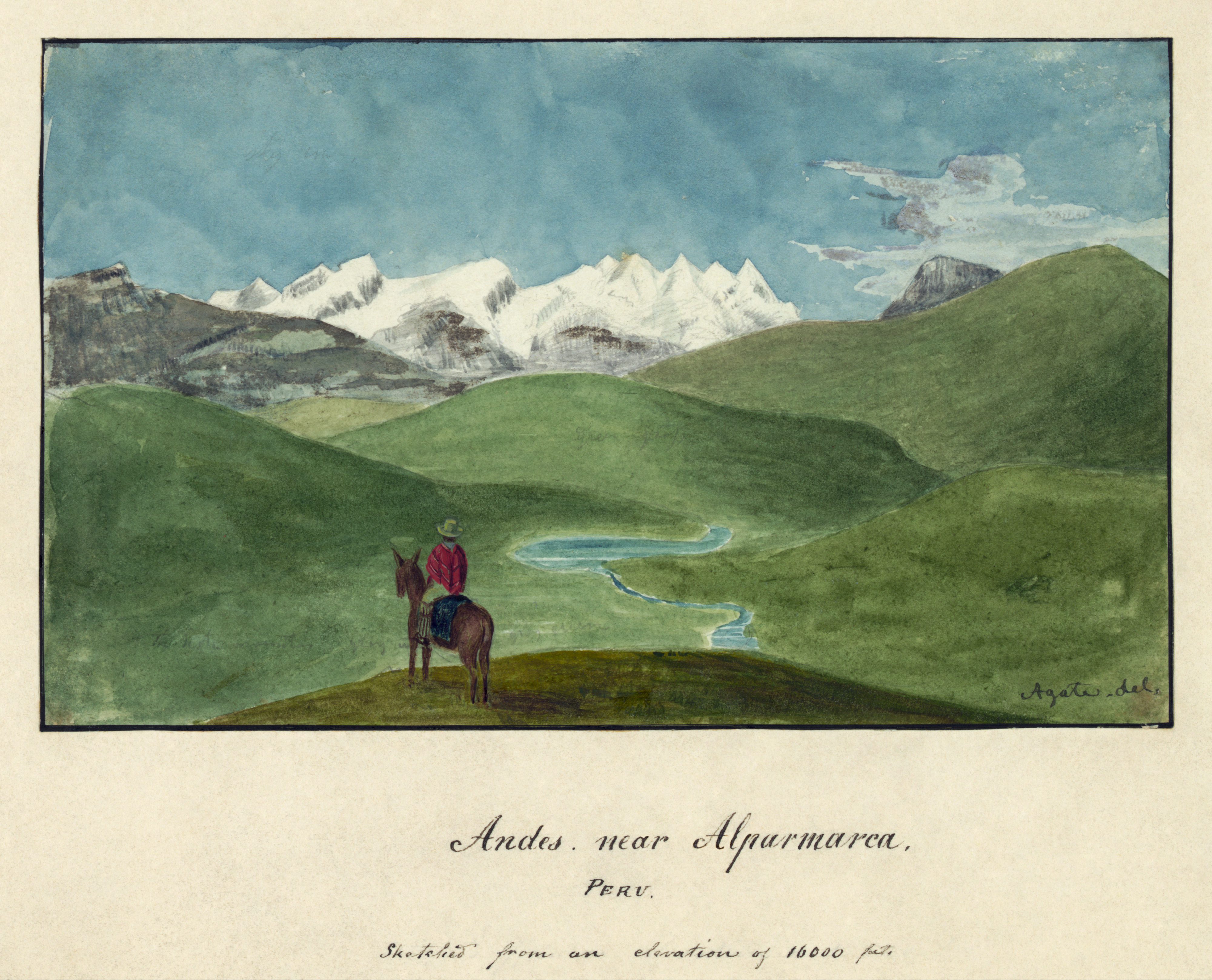

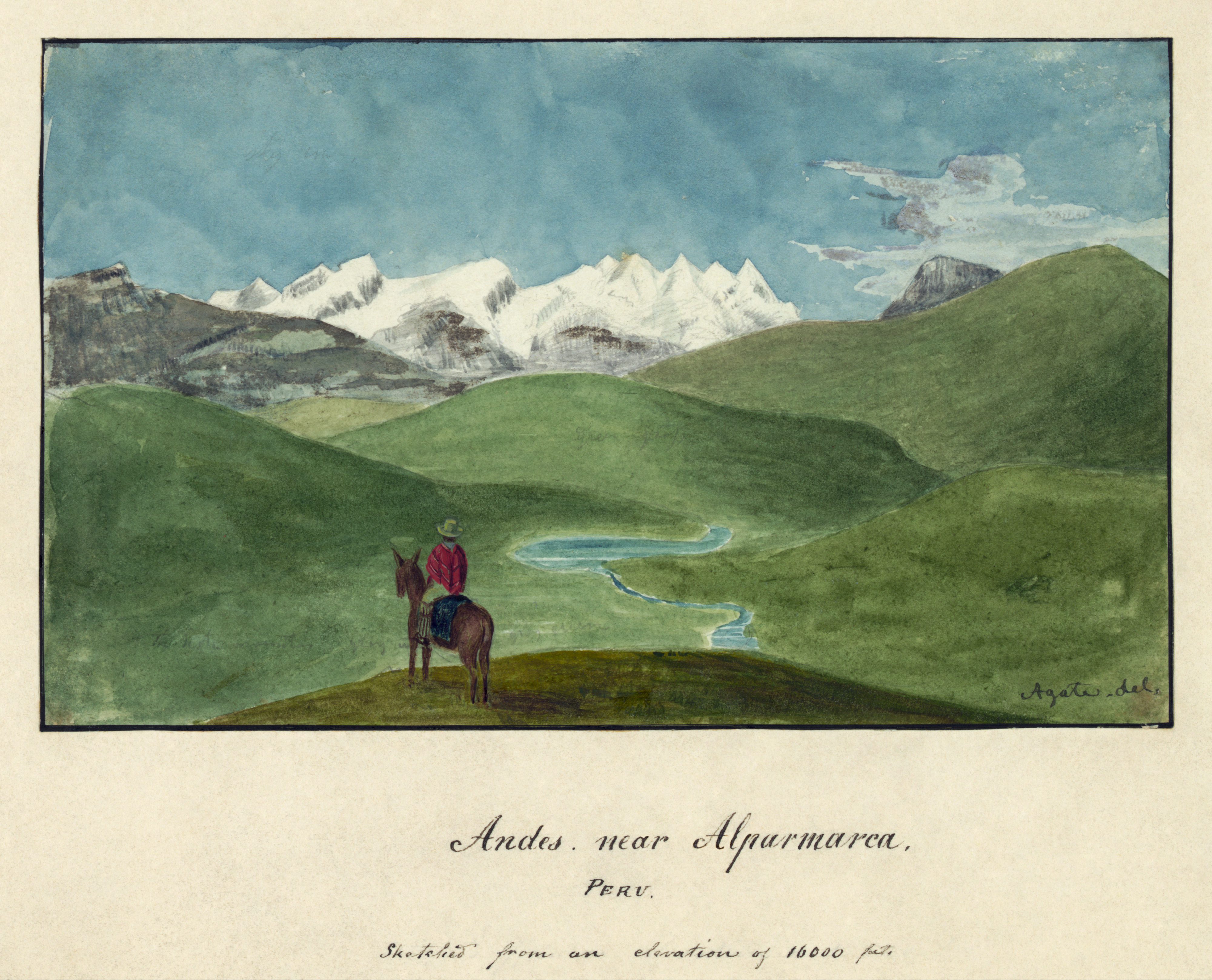

* Alfred T. Agate – Artist * James Drayton – Artist *William Brackenridge

William Dunlop Brackenridge (1810–1893) was a British-American nurseryman and botanist.

Brackenridge emigrated to Philadelphia in 1837, where he was employed by Robert Buist, nurseryman. He was appointed horticulturalist, then assistant botan ...

– Assistant botanist

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek wo ...

* Joseph P. Couthouy – Conchologist

Conchology () is the study of mollusc shells. Conchology is one aspect of malacology, the study of molluscs; however, malacology is the study of molluscs as whole organisms, whereas conchology is confined to the study of their shells. It includ ...

* James D. Dana

James Dwight Dana Royal Society of London, FRS FRSE (February 12, 1813 – April 14, 1895) was an American geologist, mineralogist, volcanologist, and zoologist. He made pioneering studies of mountain-building, volcano, volcanic activity, and the ...

– Mineralogist

Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical (including optical) properties of minerals and mineralized artifacts. Specific studies within mineralogy include the proces ...

and geologist

A geologist is a scientist who studies the solid, liquid, and gaseous matter that constitutes Earth and other terrestrial planets, as well as the processes that shape them. Geologists usually study geology, earth science, or geophysics, althou ...

* Horatio Hale

Horatio Emmons Hale (May 3, 1817 – December 28, 1896) was an American-Canadian ethnologist, philologist and businessman. He is known for his study of languages as a key for classifying ancient peoples and being able to trace their migrations. ...

– Philologist

Philology () is the study of language in oral and written historical sources; it is the intersection of textual criticism, literary criticism, history, and linguistics (with especially strong ties to etymology). Philology is also defined as th ...

* Titian Peale

Titian Ramsay Peale (November 2, 1799 – March 13, 1885) was an American artist, naturalist, and explorer from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He was a scientific illustrator whose paintings and drawings of wildlife are known for their beauty and ...

– Naturalist

* Charles Pickering – Naturalist

* William Rich – Botanist

History

Expedition

First part

Wilkes was to search forvigia

Vigia or Vigía may refer to:

Places

* Vigia (mountain), a mountain on the island of Boa Vista, Cape Verde

* Vigia, Pará, a municipality in the State of Pará, Brazil

* Vigía del Fuerte, a town in Colombia

* Finca Vigía, the house of Ernest He ...

s, or shoals, as reported by John Purdy, but failed to corroborate those claims for the locations given. The squadron arrived in the Madeira Islands

)

, anthem = ( en, "Anthem of the Autonomous Region of Madeira")

, song_type = Regional anthem

, image_map=EU-Portugal_with_Madeira_circled.svg

, map_alt=Location of Madeira

, map_caption=Location of Madeira

, subdivision_type=Sovereign st ...

on September 16, 1838, and Porto Praya

Praia (, Portuguese for "beach") is the capital and largest city of Cape Verde.Guanabara Bay

Guanabara Bay ( pt, Baía de Guanabara, ) is an oceanic bay located in Southeast Brazil in the state of Rio de Janeiro. On its western shore lie the cities of Rio de Janeiro and Duque de Caxias, and on its eastern shore the cities of Niterói and ...

for an observatory and naval yard for repair and refitting.

The Squadron did not leave Rio de Janeiro until January 6, 1839, arriving at the mouth of the Río Negro on January 25. On February 19, the squadron joined the ''Relief'', ''Flying Fish'', and ''Sea Gull'' in Orange Harbor,

The Squadron did not leave Rio de Janeiro until January 6, 1839, arriving at the mouth of the Río Negro on January 25. On February 19, the squadron joined the ''Relief'', ''Flying Fish'', and ''Sea Gull'' in Orange Harbor, Hoste Island

Hoste Island () is one of the southernmost islands in Chile, lying south, across the Beagle Channel, from Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego and west of Navarino Island, from which it is separated by the Murray Channel. Hoste Island has the souther ...

, after passing through Le Maire Strait

The Le Maire Strait (''Estrecho de le Maire'') (also the Straits Lemaire) is a sea passage between Isla de los Estados and the eastern extremity of the Argentine portion of Tierra del Fuego.

History

Jacob Le Maire and Willem Schouten discov ...

. While there, the expedition came in contact with the Fuegians

Fuegians are the indigenous inhabitants of Tierra del Fuego, at the southern tip of South America. In English, the term originally referred to the Yaghan people of Tierra del Fuego. In Spanish, the term ''fueguino'' can refer to any person from ...

. Wilkes sent an expedition south in an attempt to exceed Captain Cook

James Cook (7 November 1728 Old Style date: 27 October – 14 February 1779) was a British explorer, navigator, cartographer, and captain in the British Royal Navy, famous for his three voyages between 1768 and 1779 in the Pacific Ocean an ...

's farthest point south, 71°10'.

The ''Flying Fish'' reached 70° on March 22, in the area about north of Thurston Island

Thurston Island is an ice-covered, glacially dissected island, long, wide and in area, lying a short way off the northwest end of Ellsworth Land, Antarctica. It is the third-largest island of Antarctica, after Alexander Island and Berkner Isl ...

, and what is now called Cape Flying Fish

Cape Flying Fish (, also known as Cape Dart) is an ice-covered cape which forms the western extremity of Thurston Island. It was discovered by Richard E. Byrd and members of the US Antarctic Program in a flight from the USS ''Bear'' in Februar ...

, and the Walker Mountains

Walker Mountains () is a range of peaks and nunataks which are fairly well separated but trend east–west to form the axis, or spine, of Thurston Island in Antarctica. They were discovered by Rear Admiral Byrd and members of the US Antarctic Se ...

. The squadron joined the ''Peacock'' in Valparaiso on May 10, but the ''Sea Gull'' was reported missing. On June 6, the squadron arrived at San Lorenzo

San Lorenzo is the Italian and Spanish name for Lawrence of Rome, Saint Lawrence, the 3rd-century Christian martyr, and may refer to:

Places Argentina

* San Lorenzo, Santa Fe

* San Lorenzo Department, Chaco

* Monte San Lorenzo, a mountain on t ...

, off Callao

Callao () is a Peruvian seaside city and Regions of Peru, region on the Pacific Ocean in the Lima metropolitan area. Callao is Peru's chief seaport and home to its main airport, Jorge Chávez International Airport. Callao municipality consists o ...

for repair and provisioning, while Wilkes dispatched the ''Relief'' homewards on June 21. Leaving South America on July 12, the expedition reached Reao

Reao or Natūpe is an atoll in the eastern expanses of the Tuamotu group in French Polynesia. The closest land is Pukarua Atoll, located 48 km to the WNW.

Reao is 24.5 km long and its maximum width is 5 km. The whole length o ...

of the Tuamotu

The Tuamotu Archipelago or the Tuamotu Islands (french: Îles Tuamotu, officially ) are a French Polynesian chain of just under 80 islands and atolls in the southern Pacific Ocean. They constitute the largest chain of atolls in the world, extendin ...

Group on August 13, and Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian ; ; previously also known as Otaheite) is the largest island of the Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia. It is located in the central part of the Pacific Ocean and the nearest major landmass is Austr ...

on September 11. They departed Tahiti on October 10.

The expedition then visited

The expedition then visited Samoa

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa; sm, Sāmoa, and until 1997 known as Western Samoa, is a Polynesian island country consisting of two main islands (Savai'i and Upolu); two smaller, inhabited islands (Manono Island, Manono an ...

and New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

, Australia. In December 1839, the expedition sailed from Sydney into the Antarctic Ocean

The Southern Ocean, also known as the Antarctic Ocean, comprises the southernmost waters of the World Ocean, generally taken to be south of 60° S latitude and encircling Antarctica. With a size of , it is regarded as the second-small ...

and reported the discovery of the Antarctic continent

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest contine ...

on January 16, 1840, when Henry Eld

Henry Eld (June 2, 1814—March 12, 1850) was a United States Navy officer, geographer, and Antarctic explorer.

Biography

Eld was born in Cedar Hill, New Haven, Connecticut, on June 2, 1814, and lived in the area now known as View Street, but whe ...

and William Reynolds aboard the ''Peacock'' sighted Eld Peak

Eld Peak () is a prominent peak, high, rising southeast of Reynolds Peak on the west side of Matusevich Glacier in Antarctica. Two conical peaks were sighted in the area from the ''Peacock'' on 16 January 1840, by Passed Midshipmen Henry Eld and ...

and Reynolds Peak

Reynolds Peak () is a prominent peak (785 m) rising 6 nautical miles (11 km) northwest of Eld Peak on the west side of Matusevich Glacier. Two conical peaks were sighted in the area from the Peacock on January 16, 1840, by Passed Midshipmen ...

along the George V Coast

George V Coast () is that portion of the coast of Antarctica lying between Point Alden, at 148°2′E, and Cape Hudson, at 153°45′E.

Portions of this coast were sighted by the US Exploring Expedition in 1840. It was explored by members of t ...

. On the January 19, Reynolds spotted Cape Hudson Mawson Peninsula () is a high (), narrow, ice-covered peninsula on the George V Coast, on the west side of the Slava Ice Shelf, Antarctica, terminating in Cape Hudson. It extends for over in a northwesterly direction. The peninsula was photographed ...

. On January 25, the ''Vincennes'' sighted the mountains behind the Cook Ice Shelf

Cook Ice Shelf is an ice shelf about wide, occupying a deep recession of the coastline between Cape Freshfield and Cape Hudson, to the east of Deakin Bay.

This bay was discovered by the US Exploring Expedition in 1840, and referred to by Wil ...

, similar peaks at Piner Bay

Piner Bay is an open bay long and wide between Cape Bienvenue and the east side of Astrolabe Glacier Tongue.

Discovered on January 30, 1840, by the United States Exploring Expedition under Wilkes, who named it for Thomas Piner, signal quarterma ...

on January 30, and had covered of coastline by February 12, from 140° 30' E. to 112° 16' 12"E., when Wilkes acknowledged they had "discovered the Antarctic Continent." Named Wilkes Land

Wilkes Land is a large district of land in eastern Antarctica, formally claimed by Australia as part of the Australian Antarctic Territory, though the validity of this claim has been placed for the period of the operation of the Antarctic Treaty, ...

, it includes Claire Land

Clarie Coast, called Wilkes Coast by Australia, () is that portion of the coast of Wilkes Land lying between Cape Morse, at 130°10′E, and Pourquoi Pas Point, at 136°11′E. It was discovered in January 1840 by Captain Jules Dumont d'Urville, wh ...

, Banzare Land

Banzare Coast (), part of Wilkes Land, is that portion of the coast of Antarctica lying between Cape Southard, at 122°05′E, and Cape Morse, at 130°10′E.

This coast was spotted by the US Exploring Expedition in Feb. 1840.

It was seen from t ...

, Sabrina Land

Sabrina Coast () is that portion of the coast of Wilkes Land, Antarctica, lying between Cape Waldron, at 115° 33' E, and Cape Southard, at 122° 05' E. John Balleny has long been credited with having seen land in March 1839 at about 117° E.

The ...

, Budd Land

Budd Coast (), part of Wilkes Land, is that portion of the coast of Antarctica lying between the Hatch Islands, at 109°16'E, and Cape Waldron, at 115°33'E. It was discovered in February 1840 by the U.S. Exploring Expedition (1838–42) under th ...

, and Knox Land

Knox Coast, part of Wilkes Land, is that portion of the coast of Antarctica lying between Cape Hordern, at 100°31′E, and the Hatch Islands, at 109°16′E.

History

The coast was discovered in February 1840 by the U.S. Exploring Expedition (18 ...

. They charted of Antarctic coastline to a westward goal of 105° E., the edge of Queen Mary Land

Queen Mary Land or the Queen Mary Coast () is the portion of the coast of Antarctica lying between Cape Filchner, in 91° 54' E, and Cape Hordern, at 100° 30' E. It is claimed by Australia as part of the Australian Antarctic Territory.

It w ...

, before departing to the north again on February 21.

The ''Porpoise'' came across the French expedition of Jules Dumont d'Urville

Jules Sébastien César Dumont d'Urville (; 23 May 1790 – 8 May 1842) was a French explorer and naval officer who explored the south and western Pacific, Australia, New Zealand, and Antarctica. As a botanist and cartographer, he gave his nam ...

on January 30. However, due to a misunderstanding of each other's intentions, the Porpoise and Astrolabe

An astrolabe ( grc, ἀστρολάβος ; ar, ٱلأَسْطُرلاب ; persian, ستارهیاب ) is an ancient astronomical instrument that was a handheld model of the universe. Its various functions also make it an elaborate inclin ...

were unable to communicate. In February 1840, some of the expedition were present at the initial signing of the Treaty of Waitangi

The Treaty of Waitangi ( mi, Te Tiriti o Waitangi) is a document of central importance to the history, to the political constitution of the state, and to the national mythos of New Zealand. It has played a major role in the treatment of the M ...

in New Zealand. Some of the squadron then proceeded back to Sydney for repairs, while the rest visited the Bay of Islands

The Bay of Islands is an area on the east coast of the Far North District of the North Island of New Zealand. It is one of the most popular fishing, sailing and tourist destinations in the country, and has been renowned internationally for its ...

, before arriving in Tonga

Tonga (, ; ), officially the Kingdom of Tonga ( to, Puleʻanga Fakatuʻi ʻo Tonga), is a Polynesian country and archipelago. The country has 171 islands – of which 45 are inhabited. Its total surface area is about , scattered over in ...

in April. At Nuku'alofa they met King Josiah (Aleamotu'a), and the George (Taufa'ahau), chief of Ha'apai, before proceeding onwards to Fiji

Fiji ( , ,; fj, Viti, ; Fiji Hindi: फ़िजी, ''Fijī''), officially the Republic of Fiji, is an island country in Melanesia, part of Oceania in the South Pacific Ocean. It lies about north-northeast of New Zealand. Fiji consists ...

on May 4. The ''Porpoise'' surveyed the Low Archipelago, while the ''Vincennes'' and ''Peacock'' proceeded onwards to Ovalau, where they signed a commercial treaty with Tanoa Visawaqa

Ratu Tanoa Visawaqa (pronounced ) (died on 8 December 1852) was a Fijian Chieftain who held the title 5th Vunivalu of Bau. With Adi Savusavu, one of his nine wives, he was the father of Ratu Seru Epenisa Cakobau, who succeeded in unifying Fiji w ...

in Levuka

Levuka () is a Local government in Fiji, town on the eastern coast of the Fijian island of Ovalau (Fiji), Ovalau, in Lomaiviti Province, in the Eastern Division, Fiji, Eastern Division of Fiji. Prior to 1877, it was the capital of Fiji. At the c ...

. Edward Belcher

Admiral Sir Edward Belcher (27 February 1799 – 18 March 1877) was a British naval officer, hydrographer, and explorer. Born in Nova Scotia, he was the great-grandson of Jonathan Belcher, who served as a colonial governor of Massachuse ...

's visited Ovalau at the same time. Hudson was able to capture Vendovi, after holding his brothers Cocanauto, Qaraniqio, and Tui Dreketi (Roko Tui Dreketi

The Roko Tui Dreketi is the Paramount Chief of Fiji's Rewa Province and of the Burebasaga Confederacy, to which Rewa belongs.

Details on the title

This title is considered the second most senior in Fiji's House of Chiefs. The dynasty holding th ...

or King of Rewa Province

Rewa is a province of Fiji. With a land area of 272 square kilometers (the smallest of Fiji's provinces), it includes the capital city of Suva (but not most of Suva's suburbs) and is in two parts — one including part of Suva's hinterland to the ...

) hostage. Vendovi was deemed responsible for the attack against US sailors on Ono Island in 1836. Vendovi was taken back to the US, but died shortly after his arrival in New York. His skull was then added to the expedition collections and put on display in the Patent Office building in Washington, D.C.

In July 1840, two members of the party, Lieutenant Underwood and Wilkes' nephew, Midshipman

A midshipman is an officer of the lowest rank, in the Royal Navy, United States Navy, and many Commonwealth navies. Commonwealth countries which use the rank include Canada (Naval Cadet), Australia, Bangladesh, Namibia, New Zealand, South Afr ...

Wilkes Henry, were killed while bartering for food in western Fiji

Fiji ( , ,; fj, Viti, ; Fiji Hindi: फ़िजी, ''Fijī''), officially the Republic of Fiji, is an island country in Melanesia, part of Oceania in the South Pacific Ocean. It lies about north-northeast of New Zealand. Fiji consists ...

's Malolo

Malolo is an inhabited volcanic island in the Pacific Ocean, near Fiji. Malolo was used as a tribe name in Survivor: Ghost Island. Malolo Island is the largest of the Mamanuca Islands and is home to two villages.

History

Malolo was one of the ...

Island. The cause of this event remains equivocal. Immediately prior to their deaths, the son of the local chief, who was being held as a hostage by the Americans, escaped by jumping out of the boat and running through the shallow water for shore. The Americans fired over his head. According to members of the expedition party on the boat, his escape was intended as a prearranged signal by the Fijians to attack. According to those on shore, the shooting actually precipitated the attack on the ground. The Americans landed sixty sailors to attack the hostile natives. Close to eighty Fijians were killed in the resulting American reprisal and two villages were burned to the ground.

Return route

On August 9, after three months of surveying, the squadron met off

On August 9, after three months of surveying, the squadron met off Macuata

Macuata is one of Fiji's fourteen Provinces, and one of three based principally on the northern island of Vanua Levu, occupying the north-eastern 40 percent of the island. It has a land area of 2004 square kilometers.

The Province has 114 villa ...

. The ''Vincennes'' and ''Peacock'' proceeded onwards to the Sandwich Islands, with the ''Flying Fish'' and ''Porpoise'' to meet them in Oahu

Oahu () (Hawaiian language, Hawaiian: ''Oʻahu'' ()), also known as "The Gathering place#Island of Oʻahu as The Gathering Place, Gathering Place", is the third-largest of the Hawaiian Islands. It is home to roughly one million people—over t ...

by October. Along the way, Wilkes named the Phoenix Group

Phoenix Group Holdings plc (formerly Pearl Group plc) is a provider of insurance services based in London, England. It is listed on the London Stock Exchange and is a constituent of the FTSE 100 Index.

History

The company was founded in 1857 as ...

and made a stop at the Palmyra Atoll

Palmyra Atoll (), also referred to as Palmyra Island, is one of the Line Islands, Northern Line Islands (southeast of Kingman Reef and north of Kiribati). It is located almost due south of the Hawaiian Islands, roughly one-third of the way bet ...

, making their group the first scientific expedition in history to visit Palmyra. While in Hawaii, the officers were welcomed by Governor Kekuanaoa, King Kamehameha III

Kamehameha III (born Kauikeaouli) (March 17, 1814 – December 15, 1854) was the third king of the Kingdom of Hawaii from 1825 to 1854. His full Hawaiian name is Keaweaweula Kīwalaō Kauikeaouli Kaleiopapa and then lengthened to Keaweaweula K� ...

, his aide William Richards William, Bill, or Billy Richards may refer to:

Sportspeople

* Dicky Richards (William Henry Matthews Richards, 1862–1903), South African cricketer

* Billy Richards (footballer, born 1874) (1874–1926), West Bromwich Albion football player

* B ...

, and the journalist James Jackson Jarves

James Jackson Jarves (1818–1888) was an American newspaper editor, and art critic who is remembered above all as the first American art collector to buy Italian primitives and Old Masters.

Life and career

Jarves was the editor of an early we ...

. The expedition surveyed Kauai

Kauai, () anglicized as Kauai ( ), is geologically the second-oldest of the main Hawaiian Islands (after Niʻihau). With an area of 562.3 square miles (1,456.4 km2), it is the fourth-largest of these islands and the 21st largest island ...

, Oahu, Hawaii, and the peak of Mauna Loa

Mauna Loa ( or ; Hawaiian: ; en, Long Mountain) is one of five volcanoes that form the Island of Hawaii in the U.S. state of Hawaii in the Pacific Ocean. The largest subaerial volcano (as opposed to subaqueous volcanoes) in both mass and ...

. The ''Porpoise'' was dispatched in November to survey several of the Tuamotu

The Tuamotu Archipelago or the Tuamotu Islands (french: Îles Tuamotu, officially ) are a French Polynesian chain of just under 80 islands and atolls in the southern Pacific Ocean. They constitute the largest chain of atolls in the world, extendin ...

s, including Aratika

Aratika is an atoll in the Tuamotu group in French Polynesia. The nearest land is Kauehi Atoll, located 35 km to the south east.

Aratika has an unusual butterfly shape. Its length is and its maximum width . It has a land area of appro ...

, Kauehi

Kauehi, or Putake, is an atoll in the Tuamotu group in French Polynesia. The nearest land is Raraka Atoll, located 17 km to the Southeast. Kauehi has a wide lagoon measuring 24 km by 18 km. The atoll has a lagoon area of , and a l ...

, Raraka

Raraka, or Te Marie, is an atoll in the west of the Tuamotu group in French Polynesia. It lies 17 km to the southeast of Kauehi Atoll.

The shape of Raraka Atoll is an oval 27 km long and 19 km wide. Its fringing reef has many san ...

, and Katiu

Katiu, or Taungataki, is an atoll of the central Tuamotu Archipelago in French Polynesia. It is located west of Makemo Atoll's westernmost point. It measures in length with a maximum width of . Its total area, including the lagoon is and a la ...

, before proceeding onwards to Penrhyn Penryn is a Cornish word meaning 'headland' that may refer to:

*Penryn, Cornwall, United Kingdom, a town of about 7,000 on the Penryn River

**Penryn railway station, a station on the Maritime Line between Truro and Falmouth Docks, and serves the to ...

and returning to Oahu on 24 March.

On April 5, 1841, the squadron departed Honolulu, the ''Porpoise'' and ''Vincennes'' for the Pacific Northwest, the ''Peacock'' and ''Flying Fish'' to resurvey Samoa, before rejoining the squadron. Along the way, the ''Peacock'' and ''Flying Fish'' surveyed Jarvis Island

Jarvis Island (; formerly known as Bunker Island or Bunker's Shoal) is an uninhabited coral island located in the South Pacific Ocean, about halfway between Hawaii and the Cook Islands. It is an unincorporated, unorganized territory of the Uni ...

, Enderbury Island

Enderbury Island, also known as Ederbury Island or Guano Island, is a small, uninhabited atoll 63 km ESE of Kanton Island in the Pacific Ocean at . It is about 1 mile (1.6 km) wide and 3 miles (4.8 km) long, with a reef stretchin ...

, the Tokelau

Tokelau (; ; known previously as the Union Islands, and, until 1976, known officially as the Tokelau Islands) is a dependent territory of New Zealand in the southern Pacific Ocean. It consists of three tropical coral atolls: Atafu, Nukunonu, a ...

Islands, and Fakaofo

Fakaofo, formerly known as Bowditch Island, is a South Pacific Ocean atoll located in the Tokelau Group. The actual land area is only about 3 km2 (1.1 sq mi), consisting of islets on a coral reef surrounding a central lagoon of some 45 k ...

. The ''Peacock'' followed this with surveys of the Tuvalu

Tuvalu ( or ; formerly known as the Ellice Islands) is an island country and microstate in the Polynesian subregion of Oceania in the Pacific Ocean. Its islands are situated about midway between Hawaii and Australia. They lie east-northeast ...

islands of Nukufetau

Nukufetau is an atoll that is part of the nation of Tuvalu. The atoll was claimed by the US under the Guano Islands Act some time in the 19th century and was ceded in a treaty of friendship concluded in 1979 and coming into force in 1983. It has a ...

, Vaitupu

Vaitupu is the largest atoll of the nation of Tuvalu. It is located at 7.48 degrees south and 178.83 degrees east. There are 1,061 people (2017 Census) living on with the main village being Asau.

Geography

The island, which covers approxima ...

, and Nanumanga

Nanumanga or Nanumaga is a reef island and a district of the Oceanian island nation of Tuvalu. It has a surface area of about 3 km² with a population of 491 (2017 Census).

History

On 9 May 1824 a French government expedition under Captain ...

in March, followed by Tabiteuea

Tabiteuea (formerly Drummond's Island) is an atoll in the Gilbert Islands, Kiribati, farther south of Tarawa. This atoll is the bigger and the most populated of the Gilbert Islands but Tarawa. The atoll consists of one main island, in the nor ...

in April. Also in April, the ''Peacock'' surveyed the Gilbert Islands

The Gilbert Islands ( gil, Tungaru;Reilly Ridgell. ''Pacific Nations and Territories: The Islands of Micronesia, Melanesia, and Polynesia.'' 3rd. Ed. Honolulu: Bess Press, 1995. p. 95. formerly Kingsmill or King's-Mill IslandsVery often, this n ...

of Nonouti

Nonouti is an atoll and district of Kiribati. The atoll is located in the Southern Gilbert Islands, 38 km north of Tabiteuea, and 250 km south of Tarawa. The atoll is the third largest in the Gilbert Islands and is the island where the ...

, Aranuka

Aranuka is an atoll of Kiribati, located just north of the equator, in the Gilbert Islands. It has an area of and a population of 1,057 in 2010. By local tradition, Aranuka is the central island of the Gilbert group.

Geography

Aranuka is an a ...

, Maiana

Maiana is an atoll in Kiribati and is one of the Central Gilbert Islands. Maiana is south of the capital island of South Tarawa and has a population of 1,982 . The northern and eastern sides of the atoll are a single island, whilst the western ...

, Abemama

Abemama (Apamama) is an atoll, one of the Gilberts group in Kiribati, and is located southeast of Tarawa and just north of the Equator. Abemama has an area of and a population of 3,299 . The islets surround a deep lagoon. The eastern part of ...

, Kuria, Tarawa

Tarawa is an atoll and the capital of the Republic of Kiribati,Kiribati

'' After making another search, the man was not found and the natives began arming themselves. Lieutenant Walker returned his force to the ship, to converse with Hudson, who ordered Walker to return to shore and demand the return of the sailor. Walker then reboarded his boats with his landing party and headed to shore. Walker shouted his demand and the natives charged for him, forcing the boats to turn back to the ships. It was decided on the next day that the Americans would

After making another search, the man was not found and the natives began arming themselves. Lieutenant Walker returned his force to the ship, to converse with Hudson, who ordered Walker to return to shore and demand the return of the sailor. Walker then reboarded his boats with his landing party and headed to shore. Walker shouted his demand and the natives charged for him, forcing the boats to turn back to the ships. It was decided on the next day that the Americans would  The ''Peacock'' and ''Flying Fish'' arrived off Cape Disappointment on July 17. However, the ''Peacock'' went

The ''Peacock'' and ''Flying Fish'' arrived off Cape Disappointment on July 17. However, the ''Peacock'' went

Alfred Agate Collection

at Naval History and Heritage Command

US Exploring Expedition

– at

Video of Dr. Adrienne Kaeppler

discussing the Smithsonian Institution]

Anthropology

collections from the expedition

Charles L. Erskine's Panorama Lecture

at Dartmouth College Library {{Authority control United States Exploring Expedition, 1838 in the United States 1839 in Antarctica Artifacts in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution Circumnavigations Exploration of North America Explorers of the United States Global expeditions History of science and technology in the United States Military expeditions of the United States Oceanography Pacific expeditions Pacific Ocean United States Navy in the 19th century

''

Marakei

Marakei is a small atoll in the North Gilbert Islands. It consists of a central lagoon with numerous deep basins, surrounded by two large islands separated by two narrow channels. The atoll covers approximately .

Geography

Marakei's total land ...

, Butaritari

Butaritari is an atoll in the Pacific Ocean island nation of Kiribati. The atoll is roughly four-sided. The south and southeast portion of the atoll comprises a nearly continuous islet. The atoll reef is continuous but almost without islets al ...

, and Makin, before returning to Ohau on June 13. The ''Peacock'' and ''Flying Fish'' then left for the Columbia River

The Columbia River (Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin: ''Nch’i-Wàna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river rises in the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia, C ...

on June 21.

In April 1841, USS ''Peacock'', under Lieutenant William L. Hudson

Captain William Levereth Hudson, USN (11 May 1794 – 15 October 1862) was a United States Navy officer in the first half of the 19th century.

Career

Hudson was born 11 May 1794 in Brooklyn. His first service afloat was in the Mediterranean Squa ...

, and USS ''Flying Fish'', surveyed Drummond's Island, which was named for an American of the expedition. Lieutenant Hudson heard from a member of his crew that a ship had wrecked off the island and her crew massacred by the Gilbertese

Gilbertese or taetae ni Kiribati, also Kiribati (sometimes ''Kiribatese''), is an Austronesian language spoken mainly in Kiribati. It belongs to the Micronesian branch of the Oceanic languages.

The word ''Kiribati'', the current name of the i ...

. A woman and her child were said to be the only survivors, so Hudson decided to land a small force of marines and sailors, under William M. Walker

William is a male given name of Germanic languages, Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norm ...

, to search the island. Initially, the natives were peaceful and the Americans were able to explore the island, without results. It was when the party was returning to their ship that Hudson noticed a member of his crew was missing.

After making another search, the man was not found and the natives began arming themselves. Lieutenant Walker returned his force to the ship, to converse with Hudson, who ordered Walker to return to shore and demand the return of the sailor. Walker then reboarded his boats with his landing party and headed to shore. Walker shouted his demand and the natives charged for him, forcing the boats to turn back to the ships. It was decided on the next day that the Americans would

After making another search, the man was not found and the natives began arming themselves. Lieutenant Walker returned his force to the ship, to converse with Hudson, who ordered Walker to return to shore and demand the return of the sailor. Walker then reboarded his boats with his landing party and headed to shore. Walker shouted his demand and the natives charged for him, forcing the boats to turn back to the ships. It was decided on the next day that the Americans would bombard __NOTOC__

Bombard may refer to the act of carrying out a bombardment. It may also refer to:

Individuals

*Alain Bombard (1924–2005), French biologist, physician and politician; known for crossing the Atlantic on a small boat with no water or food

...

the hostiles and land again. While doing this, a force of around 700 Gilbertese warriors opposed the American assault, but were defeated after a long battle. No Americans were hurt, but twelve natives were killed and others were wounded, and two villages were also destroyed. A similar episode occurred two months before in February when the ''Peacock'' and the ''Flying Fish'' briefly bombarded the island of Upolu

Upolu is an island in Samoa, formed by a massive basaltic shield volcano which rises from the seafloor of the western Pacific Ocean. The island is long and in area, making it the second largest of the Samoan Islands by area. With approximatel ...

, Samoa following the death of an American merchant sailor on the island.

The ''Vincennes'' and ''Porpoise'' reached Cape Disappointment on April 28, 1841, but then headed north to the Strait of Juan de Fuca

The Strait of Juan de Fuca (officially named Juan de Fuca Strait in Canada) is a body of water about long that is the Salish Sea's outlet to the Pacific Ocean. The international boundary between Canada and the United States runs down the centre ...

, Port Discovery, and Fort Nisqually

Fort Nisqually was an important fur trading and farming post of the Hudson's Bay Company in the Puget Sound area, part of the Hudson's Bay Company's Columbia Department. It was located in what is now DuPont, Washington. Today it is a living hist ...

, where they were welcomed by William Henry McNeill

William Henry McNeill (7 July 1803 – 4 September 1875) was best known for his 1830 expedition as the captain of the brig ''Llama'' (also spelled ''Lama''), which sailed from Boston, Massachusetts, United States, around Cape Horn, to the Pacific ...

and Alexander Caulfield Anderson

Alexander Caulfield Anderson (10 March 1814 – 8 May 1884) was a British Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) fur-trader, explorer of British Columbia and civil servant.

Anderson joined HBC in 1831 and emigrated to Canada from Europe. He was placed ...

. The ''Porpoise'' surveyed the Admiralty Inlet

Admiralty Inlet is a strait in the U.S. state of Washington connecting the eastern end of the Strait of Juan de Fuca to Puget Sound. It lies between Whidbey Island and the northeastern part of the Olympic Peninsula.

Boundaries

It is generally c ...

, while boats from the ''Vincennes'' surveyed Hood Canal

Hood Canal is a fjord forming the western lobe, and one of the four main basins,Fraser River

The Fraser River is the longest river within British Columbia, Canada, rising at Fraser Pass near Blackrock Mountain in the Rocky Mountains and flowing for , into the Strait of Georgia just south of the City of Vancouver. The river's annual d ...

. Wilkes visited Fort Clatsop

Fort Clatsop was the encampment of the Lewis and Clark Expedition in the Oregon Country near the mouth of the Columbia River during the winter of 1805–1806. Located along the Lewis and Clark River at the north end of the Clatsop Plains approxim ...

, John McLoughlin

John McLoughlin, baptized Jean-Baptiste McLoughlin, (October 19, 1784 – September 3, 1857) was a French-Canadian, later American, Chief Factor and Superintendent of the Columbia District of the Hudson's Bay Company at Fort Vancouver fro ...

at Fort Vancouver

Fort Vancouver was a 19th century fur trading post that was the headquarters of the Hudson's Bay Company's Columbia Department, located in the Pacific Northwest. Named for Captain George Vancouver, the fort was located on the northern bank of the ...

, and William Cannon

William Cannon (March 15, 1809 – March 1, 1865) was an American merchant and politician from Bridgeville, in Sussex County, Delaware. He was a member of the Democratic Party and later the Republican Party, who served in the Delaware General ...

on the Willamette River

The Willamette River ( ) is a major tributary of the Columbia River, accounting for 12 to 15 percent of the Columbia's flow. The Willamette's main stem is long, lying entirely in northwestern Oregon in the United States. Flowing northward b ...

, while he sent Lt. Johnson on an expedition to Fort Okanogan

Fort Okanogan (also spelled Fort Okanagan) was founded in 1811 on the confluence of the Okanogan and Columbia Rivers as a fur trade outpost. Originally built for John Jacob Astor’s Pacific Fur Company, it was the first American-owned settlemen ...

, Fort Colvile

The trade center Fort Colvile (also Fort Colville) was built by the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) at Kettle Falls on the Columbia River in 1825 and operated in the Columbia fur district of the company. Named for Andrew Colvile,Lewis, S. William. ' ...

and Fort Nez Perces

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

, where they met Marcus Whitman

Marcus Whitman (September 4, 1802 – November 29, 1847) was an American physician and missionary.

In 1836, Marcus Whitman led an overland party by wagon to the West. He and his wife, Narcissa, along with Reverend Henry Spalding and his wife, E ...

. Like his predecessor, British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

explorer George Vancouver

Captain George Vancouver (22 June 1757 – 10 May 1798) was a British Royal Navy officer best known for his 1791–1795 expedition, which explored and charted North America's northwestern Pacific Coast regions, including the coasts of what a ...

, Wilkes spent a good deal of time near Bainbridge Island

Bainbridge Island is a city and island in Kitsap County, Washington. It is located in Puget Sound. The population was 23,025 at the 2010 census and an estimated 25,298 in 2019, making Bainbridge Island the second largest city in Kitsap County.

...

. He noted the bird-like shape of the harbor at Winslow Winslow may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Winslow, Buckinghamshire, England, a market town and civil parish

* Winslow Rural District, Buckinghamshire, a rural district from 1894 to 1974

United States and Canada

* Rural Municipality of Winslo ...

and named it Eagle Harbor Eagle Harbor may refer to several places in the United States:

* Eagle Harbor, a development on Fleming Island, Florida

* Eagle Harbor, Maryland, a town

* Eagle Harbor, Michigan, an unincorporated community and census-designated place

** Eagle Har ...

. Continuing his fascination with bird names, he named Bill Point and Wing Point. Port Madison, Washington

The Port Madison Native Reservation is an Indigenous Reservation in the U.S. state of Washington belonging to the Suquamish Tribe, a federally recognized indigenous nation and signatory to the Treaty of Point Elliott of 1855.

Location

The reserv ...

and Points Monroe and Jefferson were named in honor of former United States presidents. Port Ludlow was assigned to honor Lieutenant Augustus Ludlow __NOTOC__

Augustus C. Ludlow (1 January 1792 – 13 June 1813) was an officer in the United States Navy during the War of 1812.

Ludlow was born in Newburgh, New York. He was appointed midshipman April 2, 1804, and commissioned lieutenant June 3, 1 ...

, who lost his life during the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

.

The ''Peacock'' and ''Flying Fish'' arrived off Cape Disappointment on July 17. However, the ''Peacock'' went

The ''Peacock'' and ''Flying Fish'' arrived off Cape Disappointment on July 17. However, the ''Peacock'' went aground

Ship grounding or ship stranding is the impact of a ship on seabed or

waterway side. It may be intentional, as in beaching to land crew or cargo, and careening, for maintenance or repair, or unintentional, as in a marine accident. In accidenta ...

while attempting to enter the Columbia River and was soon lost, though with no loss of life. The crew was able to lower six boats and get everyone into Baker's Bay, along with their journals, surveys, the chronometers, and some of Agate's sketches. A one-eyed Indian named George then guided the ''Flying Fish'' into the same bay.

There, the crew set up "Peacockville", assisted by James Birnie

James Birnie (1799–1864) was an employee of the North West Company (NWC) and the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), serving primarily within the Pacific Northwest. With the Oregon Question resolved in 1846, he became the first settler of Cathlamet.

...

of the Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC; french: Compagnie de la Baie d'Hudson) is a Canadian retail business group. A fur trading business for much of its existence, HBC now owns and operates retail stores in Canada. The company's namesake business div ...

, and the American Methodist Mission at Point Adams. They also traded with the local Clatsop

The Clatsop is a small tribe of Chinookan-speaking Native Americans in the Pacific Northwest of the United States. In the early 19th century they inhabited an area of the northwestern coast of present-day Oregon from the mouth of the Columbia R ...

and Chinookan

The Chinookan languages were a small family of languages spoken in Oregon and Washington (state), Washington along the Columbia River by Chinook peoples. Although the last known native speaker of any Chinookan language died in 2012, the 2009-2013 ...

Indians over the next three weeks, while surveying the channel, before journeying to Fort George and a reunion with the rest of the squadron. This prompted Wilkes to send the ''Vincennes'' to San Francisco Bay, while he continued to survey Grays Harbor Grays Harbor is an estuary, estuarine bay located north of the mouth of the Columbia River, on the southwest Pacific coast of Washington (U.S. state), Washington state, in the United States of America. It is a ria, which formed at the end of the l ...

.

From the area of modern-day Portland

Portland most commonly refers to:

* Portland, Oregon, the largest city in the state of Oregon, in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States

* Portland, Maine, the largest city in the state of Maine, in the New England region of the northeas ...

, Wilkes sent an overland party of 39 southwards, led by Emmons, but guided by Joseph Meek

Joseph Lafayette "Joe" Meek (February 9, 1810 – June 20, 1875) was a pioneer, mountain man, law enforcement official, and politician in the Oregon Country and later Oregon Territory of the United States. A trapper involved in the fur trad ...

. The group included Agate, Eld, Colvocoresses, Brackenridge, Rich, Peale, Stearns, and Dana, and proceeded along an inland route to Fort Umpqua

Fort Umpqua was a trading post built by the Hudson's Bay Company in the company's Columbia District (or Oregon Country), in what is now the U.S. state of Oregon. It was first established in 1832 and moved and rebuilt in 1836.; online aGoogle Books/ ...

, Mount Shasta

Mount Shasta ( Shasta: ''Waka-nunee-Tuki-wuki''; Karuk: ''Úytaahkoo'') is a potentially active volcano at the southern end of the Cascade Range in Siskiyou County, California. At an elevation of , it is the second-highest peak in the Cascades ...

, the Sacramento River

The Sacramento River ( es, Río Sacramento) is the principal river of Northern California in the United States and is the largest river in California. Rising in the Klamath Mountains, the river flows south for before reaching the Sacramento–S ...

, John Sutter

John Augustus Sutter (February 23, 1803 – June 18, 1880), born Johann August Sutter and known in Spanish as Don Juan Sutter, was a Swiss immigrant of Mexican and American citizenship, known for establishing Sutter's Fort in the area th ...

's New Helvetia

New Helvetia (Spanish: Nueva Helvetia), meaning "New Switzerland", was a 19th-century Alta California settlement and Ranchos of California, rancho, centered in present-day Sacramento, California, Sacramento, California.

Colony of Nueva Helvetia

Th ...

, and then onwards to San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay is a large tidal estuary in the U.S. state of California, and gives its name to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is dominated by the big cities of San Francisco, San Jose, and Oakland.

San Francisco Bay drains water from a ...

. They departed September 7, and arrived aboard the ''Vincennes'' in Sausalito

Sausalito (Spanish for "small willow grove") is a city in Marin County, California, United States, located southeast of Marin City, south-southeast of San Rafael, and about north of San Francisco from the Golden Gate Bridge.

Sausalito's p ...

on October 23, having traveled along the Siskiyou Trail

The Siskiyou Trail stretched from California's Central Valley to Oregon's Willamette Valley; modern-day Interstate 5 follows this pioneer path. Originally based on existing Native American foot trails winding their way through river valleys, t ...

.

Wilkes arrived with the ''Porpoise'' and ''Oregon'', while the ''Flying Fish'' was to rendezvous with the squadron in Honolulu. The squadron surveyed San Francisco and its tributaries, and later produced a map of "Upper California". The expedition then headed back out on October 31, arriving Honolulu on November 17, and departing on November 28. They included a visit to Wake Island

Wake Island ( mh, Ānen Kio, translation=island of the kio flower; also known as Wake Atoll) is a coral atoll in the western Pacific Ocean in the northeastern area of the Micronesia subregion, east of Guam, west of Honolulu, southeast of To ...

, and returned by way of the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, Borneo

Borneo (; id, Kalimantan) is the third-largest island in the world and the largest in Asia. At the geographic centre of Maritime Southeast Asia, in relation to major Indonesian islands, it is located north of Java, west of Sulawesi, and eas ...

, Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, borde ...

, Polynesia

Polynesia () "many" and νῆσος () "island"), to, Polinisia; mi, Porinihia; haw, Polenekia; fj, Polinisia; sm, Polenisia; rar, Porinetia; ty, Pōrīnetia; tvl, Polenisia; tkl, Polenihia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania, made up of ...

, and the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is t ...

, reaching New York on June 10, 1842.

The expedition was plagued by poor relationships between Wilkes and his subordinate officers throughout. Wilkes' self-proclaimed status as captain and commodore, accompanied by the flying of the requisite pennant and the wearing of a captain's uniform while being commissioned only as a Lieutenant, rankled heavily with other members of the expedition of similar real rank. His apparent mistreatment of many of his subordinates, and indulgence in punishments such as " flogging round the fleet" resulted in a major controversy on his return to America. Wilkes was court-martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

led on his return, but was acquitted on all charges except that of illegally punishing men in his squadron.

Significance

The Wilkes Expedition played a major role in the development of 19th-century science, particularly in the growth of the American scientific establishment. Many of the species and other items found by the expedition helped form the basis of collections at the newSmithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

.

With the help of the expedition's scientists, derisively called "''clam digger''s" and "''bug catchers''" by navy crew members, 280 islands, mostly in the Pacific, were explored, and over of Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

were mapped. Of no less importance, over 60,000 plant and bird specimens were collected. A staggering amount of data and specimens were collected during the expedition, including the seeds of 648 species, which were later traded, planted, and sent throughout the country. Dried specimens were sent to the National Herbarium, now a part of the Smithsonian Institution. There were also 254 live plants, which mostly came from the home stretch of the journey, that were placed in a newly constructed greenhouse in 1850, which later became the United States Botanic Garden

The United States Botanic Garden (USBG) is a botanical garden on the grounds of the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C., near Garfield Circle.

The Botanic Garden is supervised by the United States Congress, Congress through the Architect ...

.

Alfred Thomas Agate

Alfred Thomas Agate (February 14, 1812 – January 5, 1846) was a noted American artist, painter and miniaturist.

Agate lived in New York from 1831 to 1838. He studied with his brother, Frederick Styles Agate, a portrait and historical painter ...

, engraver and illustrator, created an enduring record of traditional cultures such as the illustrations made of the dress and tattoo patterns of natives of the Ellice Islands

Tuvalu ( or ; formerly known as the Ellice Islands) is an island country and microstate in the Polynesian subregion of Oceania in the Pacific Ocean. Its islands are situated about midway between Hawaii and Australia. They lie east-northea ...

(now Tuvalu

Tuvalu ( or ; formerly known as the Ellice Islands) is an island country and microstate in the Polynesian subregion of Oceania in the Pacific Ocean. Its islands are situated about midway between Hawaii and Australia. They lie east-northeast ...

).

A collection of artifacts from the expedition also went to the National Institute for the Promotion of Science, a precursor of the Smithsonian Institution. These joined artifacts from American history as the first artifacts in the Smithsonian collection.

Published works

For a short time Wilkes was attached to the Office of Coast Survey, but from 1844 to 1861 he was chiefly engaged in preparing the expedition report. Twenty-eight volumes were planned, but only nineteen were published. Of these, Wilkes wrote the multi-volume ''Narrative of the United States exploring expedition, during 1838, 1839, 1840, 1841, 1842'', ''Hydrography'', and ''Meteorology''. The ''Narrative'' concerns the customs, political and economic conditions of many places then little-known. Other contributions were three reports by James Dwight Dana on ''Zoophytes'', ''Geology'', and ''Crustacea''. In addition to shorter articles and reports, Wilkes published ''Western America, including California and Oregon'', and ''Theory of the Winds''. TheSmithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

digitized the five volume narrative and the accompanying scientific volumes. The mismanagement that plagued the expedition prior to its departure continued after its completion. By June 1848, many of the specimens had been lost or damaged and many remained unidentified. In 1848 Asa Gray was hired to work on the botanical specimens, and published the first volume of the report on botany in 1854, but Wilkes was unable to secure the funding for the second volume.

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * ** * *External links

Alfred Agate Collection

at Naval History and Heritage Command

US Exploring Expedition

– at

Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

Libraries Digital Collections

Video of Dr. Adrienne Kaeppler

discussing the Smithsonian Institution]

Anthropology

collections from the expedition

Charles L. Erskine's Panorama Lecture

at Dartmouth College Library {{Authority control United States Exploring Expedition, 1838 in the United States 1839 in Antarctica Artifacts in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution Circumnavigations Exploration of North America Explorers of the United States Global expeditions History of science and technology in the United States Military expeditions of the United States Oceanography Pacific expeditions Pacific Ocean United States Navy in the 19th century