Wilberforce University on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Wilberforce University is a private historically black university in Wilberforce, Ohio. Affiliated with the

Grinnell College

Iowa, (1879, first Graduate)

New York: Oxford University Press, 1995, pp. 259–260, accessed Jan 13, 2009 Given migration patterns, this was also an area where numerous Led by Bishop

Led by Bishop

Official website

Official athletics website

1906, ''Documenting the American South'', University of North Carolina {{authority control Historically black universities and colleges in the United States Private universities and colleges in Ohio Universities and colleges affiliated with the African Methodist Episcopal Church Education in Greene County, Ohio Educational institutions established in 1856 Buildings and structures in Greene County, Ohio Universities and colleges affiliated with the Methodist Episcopal Church Antebellum educational institutions that admitted African Americans 1856 establishments in Ohio

African Methodist Episcopal Church

The African Methodist Episcopal Church, usually called the AME Church or AME, is a predominantly African American Methodist denomination. It adheres to Wesleyan-Arminian theology and has a connexional polity. The African Methodist Episcopal ...

(AME), it was the first college to be owned and operated by African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American ...

s. It participates in the United Negro College Fund

UNCF, the United Negro College Fund, also known as the United Fund, is an American philanthropic organization that funds scholarships for black students and general scholarship funds for 37 private historically black colleges and universities ...

.

Central State University

Central State University (CSU) is a public, historically black land-grant university in Wilberforce, Ohio. It is a member-school of the Thurgood Marshall College Fund.

Established by the state legislature in 1887 as a two-year program for t ...

, also in Wilberforce, Ohio, began as a department of Wilberforce University where Ohio state legislators could sponsor scholarship students.

The college was founded in 1856 by a unique collaboration between the Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state lin ...

, Ohio, Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church

The Methodist Episcopal Church (MEC) was the oldest and largest Methodist denomination in the United States from its founding in 1784 until 1939. It was also the first religious denomination in the US to organize itself on a national basis. In ...

and the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) to provide classical education and teacher training for black youth. It was named after William Wilberforce

William Wilberforce (24 August 175929 July 1833) was a British politician, philanthropist and leader of the movement to abolish the slave trade. A native of Kingston upon Hull, Yorkshire, he began his political career in 1780, eventually bec ...

. The first board members were leaders both black and white.

The outbreak of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by state ...

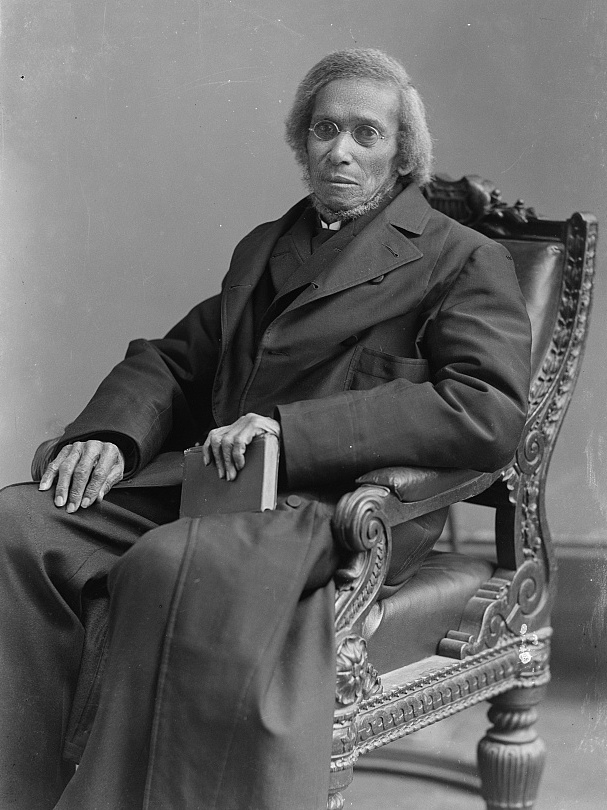

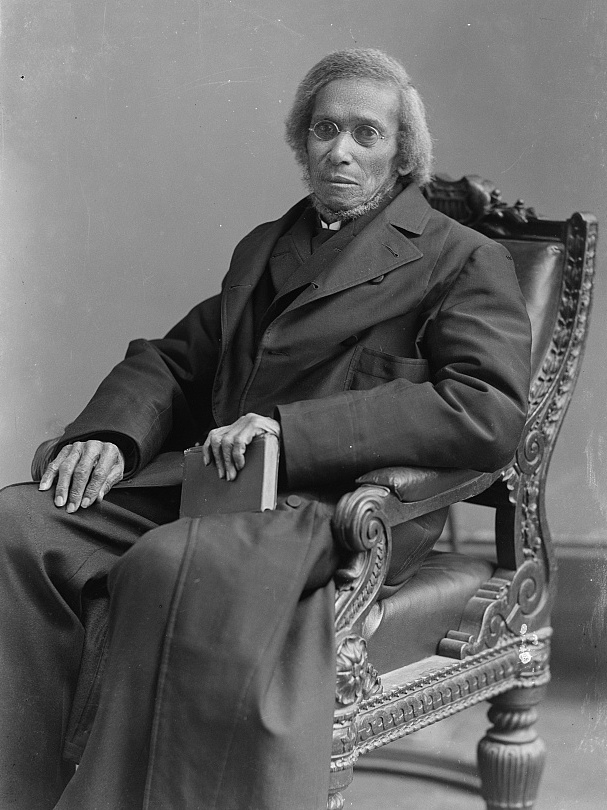

(1861–65) resulted in a decline in students from the South, who were the majority, and the college closed in 1862 because of financial losses. The AME Church purchased the institution in 1863 to ensure its survival, making it the first black-owned and operated college in the nation. AME Bishop Daniel Payne was one of the university's original founders and became its first president after re-opening; he was the first African American to become a college president in the United States. After an arson fire in 1865, the college was aided by donations from prominent white supporters and a grant from the US Congress to support rebuilding. Later it received support from the state legislature.

During the 1890s, scholar W. E. B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois ( ; February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American-Ghanaian sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist. Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up in ...

taught at the university. In the late 19th century, it enlarged its mission to include black students from South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring count ...

.

History

Wilberforce College was founded to educate African-American students. Twenty years earlier, a similar plan inNew Haven, Connecticut

New Haven is a city in the U.S. state of Connecticut. It is located on New Haven Harbor on the northern shore of Long Island Sound in New Haven County, Connecticut and is part of the New York City metropolitan area. With a population of 134,023 ...

, was met with a near-riot ( New Haven Excitement), and was quickly abandoned. (See Simeon Jocelyn.) Discrimination against Blacks was legal, and the white colleges that would accept Black students could be counted on one handGrinnell College

Iowa, (1879, first Graduate)

Hillsdale College

, mottoeng = Strength Rejoices in the Challenge

, established =

, type = Liberal arts college

, religious_affiliation = Not affiliatedBaptist (historical)

, endowment = $900 million ( ...

Michigan, the Oneida Institute, the Oberlin Collegiate Institute (later Oberlin College), and New-York Central College).

Located three miles (5 km) from the county seat of Xenia, Ohio

Xenia ( ) is a city in southwestern Ohio and the county seat of Greene County, Ohio, United States. It is east of Dayton and is part of the Dayton Metropolitan Statistical Area, as well as the Miami Valley region. The name comes from the Greek ...

in the southwestern part of the state, what developed as Wilberforce University was founded as a collaboration among leaders of the Cincinnati Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church

The Methodist Episcopal Church (MEC) was the oldest and largest Methodist denomination in the United States from its founding in 1784 until 1939. It was also the first religious denomination in the US to organize itself on a national basis. In ...

and the African Methodist Episcopal Church

The African Methodist Episcopal Church, usually called the AME Church or AME, is a predominantly African American Methodist denomination. It adheres to Wesleyan-Arminian theology and has a connexional polity. The African Methodist Episcopal ...

(AME Church). They planned to promote classical education and teacher training for black youth. Among the first 24 members of the tri-racial board of trustees in 1855 were Bishop Daniel A. Payne

Daniel Alexander Payne (February 24, 1811 – November 2, 1893) was an American bishop, educator, college administrator and author. A major shaper of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (A.M.E.), Payne stressed education and preparation of mi ...

, Rev. Lewis Woodson, and Messrs. Ishmael Keith and Alfred Anderson Alfred Anderson may refer to:

* Alfred Anderson (American football) (born 1961), former American football running back

*Alfred Anderson (entrepreneur) (1888–1956), Australian butcher and entrepreneur

* Alfred Anderson (pianist) (1848–1876), Aus ...

, all of the AME Church.Campbell (1995), ''Songs of Zion'', pp. 263 Also on the Board were Salmon P. Chase

Salmon Portland Chase (January 13, 1808May 7, 1873) was an American politician and jurist who served as the sixth chief justice of the United States. He also served as the 23rd governor of Ohio, represented Ohio in the United States Senate, a ...

, then Governor of Ohio

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

and a strong supporter of abolition

Abolition refers to the act of putting an end to something by law, and may refer to:

* Abolitionism, abolition of slavery

* Abolition of the death penalty, also called capital punishment

* Abolition of monarchy

*Abolition of nuclear weapons

*Abol ...

; a member of the Ohio State Legislature, and other Methodist leaders from the white community. They named the college after the British abolitionist and statesman William Wilberforce

William Wilberforce (24 August 175929 July 1833) was a British politician, philanthropist and leader of the movement to abolish the slave trade. A native of Kingston upon Hull, Yorkshire, he began his political career in 1780, eventually bec ...

. Rev Campbell Maxwell later became a trustee in 1896.

As a base for the college, the Cincinnati Conference bought a hotel, cottages and of a former resort property near Xenia. It was named Tawawa House after the springs in the area, a word derived from a Shawnee

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands. In the 17th century they lived in Pennsylvania, and in the 18th century they were in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, with some bands in Kentucky a ...

term for "clear or golden water". This color was associated with the natural springs nearby because of its high iron content. White people had founded the health resort in 1851 because of the springs, which they also called Yellow Springs. The waters had long been reputed to have health benefits.

Because of its location, this resort area had attracted summer people from both Cincinnati and the South, particularly after completion of the Little Miami Railroad in 1846. Some people in this area of abolitionist sentiment were shocked when wealthy white Southern planters patronized the resort with their entourages of enslaved African-American mistresses and mixed-race

Mixed race people are people of more than one race or ethnicity. A variety of terms have been used both historically and presently for mixed race people in a variety of contexts, including ''multiethnic'', ''polyethnic'', occasionally ''bi-eth ...

"natural" children.James T. Campbell, ''Songs of Zion''New York: Oxford University Press, 1995, pp. 259–260, accessed Jan 13, 2009 Given migration patterns, this was also an area where numerous

free people of color

In the context of the history of slavery in the Americas, free people of color (French: ''gens de couleur libres''; Spanish: ''gente de color libre'') were primarily people of mixed African, European, and Native American descent who were not ...

settled, many having moved across the Ohio River from the South to find better work and living conditions. Some were pushed from Southern states, which often required newly manumitted individuals to leave within a certain time period. Xenia had quite a large free black population, as did other towns in southern Ohio, such as Chillicothe, Yellow Springs and Zanesville. Free blacks and anti-slavery white supporters used houses in Xenia as stations on the Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was a network of clandestine routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early- to mid-19th century. It was used by enslaved African Americans primarily to escape into free states and Canada. ...

in the years before the Civil War. Wilberforce College also supported freedom-seeking slaves. Many of these free people of color were also had Native ancestry, Daniel Payne himself being of Catawba descent.

The college opened for classes in 1856, and by 1858 its trustees selected Rev. Richard S. Rust as the first president. Overriding some protest by men, in the 1850s the college hired Frances E. W. Harper

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (September 24, 1825 – February 22, 1911) was an American abolitionist, suffragist, poet, temperance activist, teacher, public speaker, and writer. Beginning in 1845, she was one of the first African-American women ...

, an abolitionist poet, as the first woman to teach at the school.

By 1860 the private university had more than 200 students.Talbert (1906), ''Sons of Allen'', p. 267 It is notable that most were from the South, the "natural" mixed-race

Mixed race people are people of more than one race or ethnicity. A variety of terms have been used both historically and presently for mixed race people in a variety of contexts, including ''multiethnic'', ''polyethnic'', occasionally ''bi-eth ...

sons and daughters of wealthy white planters and their enslaved African-American mistresses. The fathers paid for the educations that were denied their children in the South. They were among the fathers who did not abandon their mixed-race children but provided them with the social capital

Social capital is "the networks of relationships among people who live and work in a particular society, enabling that society to function effectively". It involves the effective functioning of social groups through interpersonal relationship ...

of education and sometimes property.

The outbreak of the Civil War threatened the college's finances. The Southern planters withdrew their children, and no more paying students came from the South. The Methodist church said it had to divert its resources to support the war. The college closed temporarily in 1862 when the Cincinnati Methodist Church was unable to fund it fully.

Led by Bishop

Led by Bishop Daniel A. Payne

Daniel Alexander Payne (February 24, 1811 – November 2, 1893) was an American bishop, educator, college administrator and author. A major shaper of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (A.M.E.), Payne stressed education and preparation of mi ...

, in 1863 the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) decided to buy the college to ensure its survival; they paid the cost of its debt. They sold another property to raise the money. Founders were Bishop Payne, who was selected as its president; James A. Shorter

James A. Shorter, Jr. was a farmer, teacher, and state legislator in Mississippi. He served in the Mississippi House of Representatives

The Mississippi House of Representatives is the lower house of the Mississippi Legislature, the lawmaki ...

, pastor of the AME Church in Zanesville, Ohio

Zanesville is a city in and the county seat of Muskingum County, Ohio, United States. It is located east of Columbus and had a population of 24,765 as of the 2020 census, down from 25,487 as of the 2010 census. Historically the state capital ...

and a future bishop; and Dr. John G. Mitchell, principal of the Eastern District Public School of Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state lin ...

. Payne was the first African American to become a college president in the United States.

When an arson

Arson is the crime of willfully and deliberately setting fire to or charring property. Although the act of arson typically involves buildings, the term can also refer to the intentional burning of other things, such as motor vehicles, wat ...

fire damaged some of the buildings in 1865, Payne went to his network to appeal for aid in rebuilding the college. Salmon P. Chase

Salmon Portland Chase (January 13, 1808May 7, 1873) was an American politician and jurist who served as the sixth chief justice of the United States. He also served as the 23rd governor of Ohio, represented Ohio in the United States Senate, a ...

, then Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point ...

, and Dr. Charles Avery from Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Wester ...

each contributed $10,000 to rebuild the college. Mary E. Monroe, another white supporter, contributed $4200. In addition, the US Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washi ...

approved a $25,000 grant for the college, which raised additional monies privately from a wide range of donors.

In 1888 the AME Church came to an agreement with the Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

*Republican Party (Liberia)

* Republican Part ...

-dominated state legislature that brought considerable financial support and political patronage to the college. It negotiated contemporary pressures to emphasize industrial education for many black youth by accommodating both that and the classical education.

As an act of political patronage, the state legislature established a commercial, normal and industrial (CNI) department at Wilberforce College. While this created complications for administration and questions about the mission of the college, in the near term it brought tens of thousands of dollars annually in state aid to the campus. Each state legislator could award an annual scholarship to the CNI department at Wilberforce, enabling hundreds of African-American students to attend classes. The state-funded students could complete liberal arts at the college, and students at Wilberforce could also take "industrial" classes.

By the mid-1890s, the college also admitted students from South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring count ...

, as part of the AME Church's mission to Africa. The church helped support such students with scholarships, as well as arranging board with local families. An 1898 report published by the AME Church listed the university as having 20 faculty, 334 students, and 246 graduates.

The college became a center of black cultural and intellectual life in southwestern Ohio. Because the area did not receive many European immigrants, blacks had more opportunities at diverse work. Xenia and nearby towns developed a professional black elite.

Generations of leaders: teachers, ministers, doctors, politicians and college administrators, and later men and women of all occupations, have been educated at the university. In the 19th century, Bishop Payne established his dream, a theological seminary

A seminary, school of theology, theological seminary, or divinity school is an educational institution for educating students (sometimes called ''seminarians'') in scripture, theology, generally to prepare them for ordination to serve as clergy, ...

, which was named in his honor. Top-ranking scholars taught at the college, including W.E.B. Du Bois, the philologist

Philology () is the study of language in oral and written historical sources; it is the intersection of textual criticism, literary criticism, history, and linguistics (with especially strong ties to etymology). Philology is also defined as ...

William S. Scarborough

William Sanders Scarborough (February 16, 1852 – September 9, 1926) is generally thought to be the first African American classical scholar. Born into slavery, Scarborough served as president of Wilberforce University between 1908 and 1920. He ...

, Edward Clarke, and John G. Mitchell, dean of the seminary. In 1894 Lieutenant Charles Young, the third black graduate of West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

and at the time the only African-American commissioned officer in the US Army, led the newly established military science department.

Additional leading scholars taught at the college in the early 20th century, such as Theophilus Gould Steward, a politician, theologian and missionary

A missionary is a member of a Religious denomination, religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Tho ...

; and the sociologist Richard R. Wright, Jr., the first African American to earn a PhD from the University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (also known as Penn or UPenn) is a private research university in Philadelphia. It is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and is ranked among the highest-regarded universit ...

. He was a future AME bishop and became president of Wilberforce. These men were also prominent in the American Negro Academy, founded in 1897 to support the work of scholars, writers and other intellectuals. In 1969 the organization was revived as the Black Academy of Arts and Letters The Black Academy of Arts and Letters was an organization founded on March 27, 1969 in Boston. The organization was "dedicated to the defining and promoting cultural achievement of black people." According to its founder, Dr. C. Eric Lincoln, "A Bla ...

.

In 1941, the normal/industrial department was expanded by development of a four-year curriculum. In 1947, this section was split from the university and given independent status. It was renamed as Central State College in 1951. With further development of programs and departments, in 1965 it achieved university status as Central State University

Central State University (CSU) is a public, historically black land-grant university in Wilberforce, Ohio. It is a member-school of the Thurgood Marshall College Fund.

Established by the state legislature in 1887 as a two-year program for t ...

.

Growth of Wilberforce University after the mid-20th century led to construction of a new campus in 1967, located one mile (1.6 km) away. In 1974, the area was devastated by an F5 tornado that was part of the 1974 Super Outbreak

The 1974 Super Outbreak was the second-largest tornado outbreak on record for a single 24-hour period, just behind the 2011 Super Outbreak. It was also the most violent tornado outbreak ever recorded, with 30 F4/F5 tornadoes confirmed. From Apr ...

, which destroyed much of the city of Xenia and the old campus of Wilberforce.

Older campus buildings still in use include the Carnegie Library, built in 1909 with matching funds from the Carnegie Foundation, and listed on the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artist ...

; Shorter Hall, built in 1922; and the Charles Leander Hill Gymnasium, built in 1958. The former residence of Charles Young near Wilberforce was designated as a National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the United States government for its outstanding historical significance. Only some 2,500 (~3%) of over 90,000 places listed ...

by the US Department of Interior, in recognition of his significant and groundbreaking career in the US Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, c ...

.

In the 1970s, the university established the National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center, to provide exhibits and outreach to the region. It is now operated by the Ohio Historical Society

Ohio History Connection, formerly The Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society and Ohio Historical Society, is a nonprofit organization incorporated in 1885. Headquartered at the Ohio History Center in Columbus, Ohio, Ohio History Connec ...

. The university also supports the national Association of African American Museums, to provide support and professional guidance especially to smaller museums across the country.

In 2021 the university announced it was cutting tuition by 15% for Ohio residents.

2008 Financial aid audit

In 2008 the US Department of Education, Office of the Inspector General (OIG) completed an audit of financial management, specifically the university's management of Title IV funds, which related to its work-study program. For the two-year audit period (2004–2005, 2005–2006) the audit found numerous faults. In summary, the OIG found that the university did not comply with Title IV, HEA requirements because of administrative problems, including staff turnover, insufficient financial aid staff, failure to have written procedures, and lack of communication with other offices. The university worked with auditors to set up appropriate staff and procedures.Presidents

* Richard Rust, 1858–1862 (under the joint board of trustees representing the Methodist Episcopal and African Methodist Episcopal churches) *Daniel A. Payne

Daniel Alexander Payne (February 24, 1811 – November 2, 1893) was an American bishop, educator, college administrator and author. A major shaper of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (A.M.E.), Payne stressed education and preparation of mi ...

, 1863–1876, first president of the college under AME operation

* Benjamin F. Lee

Benjamin Franklin Lee (September 18, 1841 – March 12, 1926) was a religious leader and educator in the United States. He was the president of Wilberforce University from 1876 to 1884. He was editor of the ''Christian Recorder'' from 1884 to 189 ...

, 1876–1884

* Samuel T. Mitchell, 1884–1900

* Joshua H. Jones, 1900–1908

* William S. Scarborough

William Sanders Scarborough (February 16, 1852 – September 9, 1926) is generally thought to be the first African American classical scholar. Born into slavery, Scarborough served as president of Wilberforce University between 1908 and 1920. He ...

, 1908–1920

* John A. Gregg, 1920–1924

* Gilbert H. Jones, 1924–1932

* Richard R. Wright, Jr., 1932–1936, 1941–1942

* D. Ormonde Walker, 1936–1941

* Charles H. Wesley

Charles Harris Wesley (December 2, 1891 – August 16, 1987) was an American historian, educator, minister, and author. He published more than 15 books on African-American history, taught for decades at Howard University, and served as president ...

, 1942–1947

* Charles Leander Hill

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English language, English and French language, French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic, Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*k ...

, 1947–1956

* Rembert E. Stokes, 1956–1976

* Charles E. Taylor, 1976–1984

* Yvonne Walker Taylor, 1984–1988

* John L. Henderson, 1988–2002

* Floyd Flake, 2002–2008

* Patricia Hardaway, 2009–2013,

* Wilma Mishoe, interim

* Algeania Marie Warren Freeman, 2014–2016, former president of Livingstone College and Martin University

* Herman J. Felton, Jr., 2016–2018

* Elfred Anthony Pinkard, 2018–present

Academics

Cooperative education

Wilberforce requires all students to participate incooperative education

Cooperative education (or co-operative education) is a structured method of combining classroom-based education with practical work experience. A cooperative education experience, commonly known as a "co-op", provides academic credit for struct ...

to meet graduation requirements. The cooperative program places students in internships that provide practical work experience in addition to academic training. It has been a required part of the curriculum at Wilberforce since 1966.

NASA SEMAA project

In October 2006, Wilberforce held the grand opening and dedication for theNASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research.

NASA was established in 1958, succeedi ...

Science, Engineering, Mathematics and Aerospace Academy (SEMAA) and the associated Aerospace Education Laboratory (AEL). It was attended by Dr. Bernice G. Alston, deputy assistant administrator of NASA's office of Education, and the Dave Hobson, U.S. Representative from Ohio's 7th congressional district.

NASA's program was designed to provide training in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics to underprivileged students to support NASA's future needs. There were 17 NASA SEMAA project sites through the United States. Through this partnership, Wilberforce offered training sessions for students in grades K-12 during the academic year and during the summer. The AEL is computerized classroom that provided technology to students in grades 7–12 that supported the SEMAA training sessions.

Student activities

NPHC organizations

All nine of theNational Pan-Hellenic Council

The National Pan-Hellenic Council (NPHC) is a collaborative umbrella council composed of historically African American fraternities and sororities also referred to as Black Greek Letter Organizations (BGLOs). The NPHC was formed as a permanent ...

organizations currently have chapters at Wilberforce University. These organizations are:

Athletics

The Wilberforce athletic teams are called the Bulldogs. The university is a member of theNational Association of Intercollegiate Athletics

The National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA) established in 1940, is a college athletics association for colleges and universities in North America. Most colleges and universities in the NAIA offer athletic scholarships to its stud ...

(NAIA), primarily competing in the Mid-South Conference

The Mid-South Conference (MSC) is a college athletic conference affiliated with the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA). Member institutions are located in Kentucky, Ohio, and Tennessee. The league is headquartered in Lo ...

(MSC) since the 2022–23 academic year. The Bulldogs previously competed as an NAIA Independent within the Continental Athletic Conference from 2012–13 to 2021–22, and in the defunct American Mideast Conference from 1999–2000 to 2011–12.

Wilberforce competes in 11 intercollegiate varsity sports: Men's sports include basketball, cross country, golf and track & field (indoor and outdoor); while women's sports include basketball, cross country, golf, spirit teams and track & field (indoor and outdoor).

Intramurals

Students also participate in the following intramural sports: basketball, softball, volleyball, flag football, and tennis.Notable alumni

See also

*Historically black colleges and universities

Historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) are institutions of higher education in the United States that were established before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 with the intention of primarily serving the African-American community. M ...

Representation in other media

*Dolen Perkins-Valdez

Dolen Perkins-Valdez is an American writer, best known for her debut novel '' Wench: A Novel'' (2010), which became a bestseller.

She is Chair of the Board of the PEN/Faulkner Foundation Board of Directors.

Early life and education

She attended ...

's novel ''Wench'' (2010) explores the lives of several enslaved women of color brought to the Tawawa House resort during the summers by their Southern white masters. They were among the visitors in the years before the property was bought for use as the college.

References

External links

Official website

Official athletics website

1906, ''Documenting the American South'', University of North Carolina {{authority control Historically black universities and colleges in the United States Private universities and colleges in Ohio Universities and colleges affiliated with the African Methodist Episcopal Church Education in Greene County, Ohio Educational institutions established in 1856 Buildings and structures in Greene County, Ohio Universities and colleges affiliated with the Methodist Episcopal Church Antebellum educational institutions that admitted African Americans 1856 establishments in Ohio