Whaling In America on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Commercial whaling in the United States dates to the 17th century in

Commercial whaling in the United States dates to the 17th century in

The American whaling fleet, after steadily growing for 50 years, reached its all-time peak of 199,000 tons in 1858. Just two years later, in 1860, just before the Civil War, the fleet had dropped to 167,000 tons. The war cut into whaling temporarily, but only 105,000 whaling tons returned to sea in 1866, the first full year of peace, and that number dwindled until only 39 American ships set out to hunt whales in 1876.

During the winter, some of these same vessels would make their way to the lagoons of

The American whaling fleet, after steadily growing for 50 years, reached its all-time peak of 199,000 tons in 1858. Just two years later, in 1860, just before the Civil War, the fleet had dropped to 167,000 tons. The war cut into whaling temporarily, but only 105,000 whaling tons returned to sea in 1866, the first full year of peace, and that number dwindled until only 39 American ships set out to hunt whales in 1876.

During the winter, some of these same vessels would make their way to the lagoons of  The use of steam, the high prices for

The use of steam, the high prices for  Ships continued to overwinter at Herschel into the 20th century, but by that time they focused more on trading with the natives than on whaling. By 1909 there were only three whaleships left in the

Ships continued to overwinter at Herschel into the 20th century, but by that time they focused more on trading with the natives than on whaling. By 1909 there were only three whaleships left in the

In Alaska, bowhead whale and beluga whale hunts are regulated by the

In Alaska, bowhead whale and beluga whale hunts are regulated by the

According to Frances Diane Robotti, there were three types of whalemen: those who hoped to own their own whaleship someday, those who were seeking adventure, and those who were running from something on shore. Generally only those who hoped to make a career of whaling went out more than once.

Since a whaleman's pay was based on his "lay", or share of the catch, he sometimes returned from a long voyage to find himself paid next to nothing, or even owing money to his employers. Even a bonanza voyage paid the ordinary crewman less than if he had served in the merchant fleet. The lay system was a gamble and sailors were never ensured decent wages. Richard Boyenton of the "Bengal" only earned six and a quarter cents after five months at sea, but occasionally sailors got lucky and brought home a significant amount of money after just a couple of voyages. More commonly sailors would earn very little after years at sea. Ships that returned to port less than full of oil were called "broken voyages" while ships that came home overflowing were praised. The ''Loper'' returned to Nantucket with its deck and hold chock full of casks of oil while ships like the ''Brewster'' prioritized oil so significantly that they threw food and water overboard to make more room for oil.

Going to sea was a young man's adventure, particularly when he wound up in the South Sea paradises of the

According to Frances Diane Robotti, there were three types of whalemen: those who hoped to own their own whaleship someday, those who were seeking adventure, and those who were running from something on shore. Generally only those who hoped to make a career of whaling went out more than once.

Since a whaleman's pay was based on his "lay", or share of the catch, he sometimes returned from a long voyage to find himself paid next to nothing, or even owing money to his employers. Even a bonanza voyage paid the ordinary crewman less than if he had served in the merchant fleet. The lay system was a gamble and sailors were never ensured decent wages. Richard Boyenton of the "Bengal" only earned six and a quarter cents after five months at sea, but occasionally sailors got lucky and brought home a significant amount of money after just a couple of voyages. More commonly sailors would earn very little after years at sea. Ships that returned to port less than full of oil were called "broken voyages" while ships that came home overflowing were praised. The ''Loper'' returned to Nantucket with its deck and hold chock full of casks of oil while ships like the ''Brewster'' prioritized oil so significantly that they threw food and water overboard to make more room for oil.

Going to sea was a young man's adventure, particularly when he wound up in the South Sea paradises of the

A large number of crewmen on American, British, and other countries vessels that participated in whaling in the 19th century created

A large number of crewmen on American, British, and other countries vessels that participated in whaling in the 19th century created

''Whaling Will Never Do for Me: The American Whaleman in the Nineteenth Century''

The University Press of Kentucky. . * * George, G. D. and R. G. Bosworth (April 1988)

''Use of Fish and Wildlife by Residents of Angoon, Admiralty Island, Alaska''

* *

"Race Revive Old Whaling Days of Old" ''Popular Mechanics'', November 1930

"A Brief History of Pacific Coast Whaling"

by Nicholas J. Lee * Federal Writers' Project of the Works Progress Administration of Massachusetts (1938).

Whaling Masters: Voyages, 1731–1925

'. New Bedford, Mass.: Published by the Old Dartmouth Historical Society.

''Into the Deep: America, Whaling & The World''

a 2010 documentary film by

The Papers of Leander Owens, Whaling Captain

at Dartmouth College Library

Frederick W. Maurer "Belvedere" Narrative (1911-1912) Manuscript

at Dartmouth College Library

Francis Brown Collection on the Whaler 'Canada'

at Dartmouth College Library {{Whaling, state=collapsed Economic history of the United States Maritime history of the United States Natural history of the United States Cape Verdean American history

Commercial whaling in the United States dates to the 17th century in

Commercial whaling in the United States dates to the 17th century in New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

. The industry peaked in 1846–1852, and New Bedford, Massachusetts

New Bedford (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ) is a city in Bristol County, Massachusetts, Bristol County, Massachusetts. It is located on the Acushnet River in what is known as the South Coast (Massachusetts), South Coast region. Up throug ...

, sent out its last whaler

A whaler or whaling ship is a specialized vessel, designed or adapted for whaling: the catching or processing of whales.

Terminology

The term ''whaler'' is mostly historic. A handful of nations continue with industrial whaling, and one, Japa ...

, the ''John R. Mantra'', in 1927. The Whaling industry was engaged with the production of three different raw materials: whale oil

Whale oil is oil obtained from the blubber of whales. Whale oil from the bowhead whale was sometimes known as train oil, which comes from the Dutch word ''traan'' ("tears, tear" or "drop").

Sperm oil, a special kind of oil obtained from the ...

, spermaceti oil, and whalebone

Baleen is a filter-feeding system inside the mouths of baleen whales. To use baleen, the whale first opens its mouth underwater to take in water. The whale then pushes the water out, and animals such as krill are filtered by the baleen and re ...

. Whale oil was the result of "trying-out" whale blubber by heating in water. It was a primary lubricant for machinery, whose expansion through the Industrial Revolution depended upon before the development of petroleum-based lubricants in the second half of the 19th century. Once the prized blubber and spermaceti had been extracted from the whale, the remaining majority of the carcass was discarded.

Spermaceti oil came solely from the head-case of sperm whales. It was processed by pressing the material rather than "trying-out". It was more expensive than whale oil, and highly regarded for its use in illumination, by burning the oil on cloth wicks or by processing the material into spermaceti candles, which were expensive and prized for their clean-burning properties. Chemically, spermaceti is more accurately classified as a wax rather than an oil.

Whalebone was baleen plates from the mouths of the baleen whales. Whalebone was commercially used to manufacture materials that required light but strong and thin supports. Women's corsets, umbrella and parasol ribs, crinoline petticoats, buggy whips and collar-stiffeners were commonly made of whalebone. Public records of exports of these three raw materials from the United States date back to 1791, and products of New England whaling represented a major portion of the American GDP for nearly 100 years.

Historic Aboriginal whaling

Indigenous whaling is the hunting of whales by indigenous peoples recognised by either IWC (International Whaling Commission) or the hunting is considered as part of indigenous activity by the country. It is permitted under international regu ...

within the boundaries of today's United States predated the arrival of European explorers, and is still practiced using the exception granted by the International Whaling Commission

The International Whaling Commission (IWC) is a specialised regional fishery management organisation, established under the terms of the 1946 International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling (ICRW) to "provide for the proper conservation of ...

, which allows some subsistence hunting by Native Americans for cultural reasons. Catches have increased from 18 whales in 1985 to over 70 in 2010. The latest IWC quota regarding the subsistence hunting of the bowhead whale

Subsistence hunting of the bowhead whale is permitted by the International Whaling Commission, under limited conditions. While whaling is banned in most parts of the world, some of the Native peoples of North America, including the Eskimo and ...

allowed for up to 336 to be killed in the period 2013–2018. Residents of the United States are also subject to U.S. Federal government bans against whaling as well.

History

New England

The commercial whaling fishery in the United States is thought to have begun in the 1650s with a series of contracts between Southampton, Long Island resident English settlers John Ogden, John Cooper and theShinnecock Indians

The Shinnecock Indian Nation is a federally recognized tribe of historically Algonquian peoples, Algonquian-speaking Native Americans in the United States, Native Americans based at the eastern end of Long Island, New York. This tribe is headqua ...

. Prior to this, they chased pilot whale

Pilot whales are cetaceans belonging to the genus ''Globicephala''. The two extant species are the long-finned pilot whale (''G. melas'') and the short-finned pilot whale (''G. macrorhynchus''). The two are not readily distinguishable at sea, a ...

s ("blackfish") onto the shelving beaches for slaughter, a sort of dolphin drive hunting

Dolphin drive hunting, also called dolphin drive fishing, is a method of hunting dolphins and occasionally other small cetaceans by driving them together with boats and then usually into a bay or onto a beach. Their escape is prevented by closing ...

. Nantucket

Nantucket () is an island about south from Cape Cod. Together with the small islands of Tuckernuck and Muskeget, it constitutes the Town and County of Nantucket, a combined county/town government that is part of the U.S. state of Massachuse ...

joined in on the trade in 1690 when they sent for one Ichabod Padduck to instruct them in the methods of whaling.

The south side of the island was divided into three and a half mile sections, each one with a mast erected to look for the spouts of right whale

Right whales are three species of large baleen whales of the genus ''Eubalaena'': the North Atlantic right whale (''E. glacialis''), the North Pacific right whale (''E. japonica'') and the Southern right whale (''E. australis''). They are clas ...

s. Each section had a temporary hut for the five men assigned to that area, with a sixth man standing watch at the mast. Once a whale was sighted, whale boat

A whaleboat is a type of open boat that was used for catching whales, or a boat of similar design that retained the name when used for a different purpose. Some whaleboats were used from whaling ships. Other whaleboats would operate from the sh ...

s were rowed from the shore, and if the whale was successfully harpoon

A harpoon is a long spear-like instrument and tool used in fishing, whaling, seal hunting, sealing, and other marine hunting to catch and injure large fish or marine mammals such as seals and whales. It accomplishes this task by impaling the t ...

ed and lanced to death, it was towed ashore, flensed (i.e., its blubber was cut off), and the blubber rendered into whale oil

Whale oil is oil obtained from the blubber of whales. Whale oil from the bowhead whale was sometimes known as train oil, which comes from the Dutch word ''traan'' ("tears, tear" or "drop").

Sperm oil, a special kind of oil obtained from the ...

in cauldrons known as "try pot

A try pot is a large pot used to remove and render the oil from blubber obtained from cetaceans (whales and dolphins) and pinnipeds (seals), and also to extract oil from penguins. Once a suitable animal such as a whale had been caught and killed ...

s." Well into the 18th century, even when Nantucket sent out sailing vessels to fish for whales offshore, the whalers would still come to the shore to boil the blubber.

In 1715, Nantucket had six sloops engaged in whale fishery, and by 1730 it had 25 vessels of 38 to 50 tons involved in the trade. Each vessel employed 12 to 13 men, half of them being Native Americans. At times the entire crew, with the exception of the captain, might be natives. They had two whaleboats, one held in reserve should the other be damaged by a whale. By 1732, the first New England whalers had reached the Davis Strait

Davis Strait is a northern arm of the Atlantic Ocean that lies north of the Labrador Sea. It lies between mid-western Greenland and Baffin Island in Nunavut, Canada. To the north is Baffin Bay. The strait was named for the English explorer Jo ...

fishery, between Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland is t ...

and Baffin Island

Baffin Island (formerly Baffin Land), in the Canadian territory of Nunavut, is the largest island in Canada and the fifth-largest island in the world. Its area is , slightly larger than Spain; its population was 13,039 as of the 2021 Canadia ...

. The fishery slowly began to expand, with whalers visiting the coast of West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, Maurit ...

in 1763, the Azores

)

, motto =( en, "Rather die free than subjected in peace")

, anthem= ( en, "Anthem of the Azores")

, image_map=Locator_map_of_Azores_in_EU.svg

, map_alt=Location of the Azores within the European Union

, map_caption=Location of the Azores wi ...

in 1765, the coast of Brazil in 1773, and the Falklands

The Falkland Islands (; es, Islas Malvinas, link=no ) is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and about from Cape Dubouzet ...

in 1774. It wasn't until the 19th century that whaling really became an industry.

Expansion

In 1768, the fishery began a huge expansion that was to culminate just prior to theAmerican Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

. Between 1771 and 1775 the Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

ports alone employed an average of 183 vessels in the northern fishery, and 121 in the southern. During the American Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars there was a complete shutdown of the industry, its peak growth came after the American Revolution.

The first New England whalers rounded Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramírez ...

in 1791, entering the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

to hunt the cachalot or sperm whale

The sperm whale or cachalot (''Physeter macrocephalus'') is the largest of the toothed whales and the largest toothed predator. It is the only living member of the genus ''Physeter'' and one of three extant species in the sperm whale famil ...

. At first they only fished off the coast of Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

, but by 1792, the sperm whalers had reached the coast of Peru, and George W. Gardner extended the fishery even further in 1818 when he discovered the "offshore grounds," or the seas between 105–125° W and 5–10° S. In 1820, the first New England whaleship, the , under Captain Joseph Allen, hunted sperm whales on the Japanese ground, midway between Japan and Hawaii. The previous year the first New England whalers visited the Sandwich (Hawaiian) Islands, and subsequently these islands were used to obtain fresh fruits, vegetables, and more crew, as well as to repair any damages sustained to the ship.

In 1829 the New England fleet numbered 203 sail; in five years time it more than doubled to 421 vessels, and by 1840 it stood at 552 ships, barks, brigs, and schooners. The peak was reached in 1846, when 736 vessels were registered under the American flag. From 1846 to 1851, the trade averaged some 638 vessels, with the majority coming from such ports as New Bedford

New Bedford (Massachusett: ) is a city in Bristol County, Massachusetts. It is located on the Acushnet River in what is known as the South Coast region. Up through the 17th century, the area was the territory of the Wampanoag Native American pe ...

and Nantucket, Massachusetts

Nantucket () is an island about south from Cape Cod. Together with the small islands of Tuckernuck and Muskeget, it constitutes the Town and County of Nantucket, a combined county/town government that is part of the U.S. state of Massachuse ...

; New London, Connecticut

New London is a seaport city and a port of entry on the northeast coast of the United States, located at the mouth of the Thames River in New London County, Connecticut. It was one of the world's three busiest whaling ports for several decades ...

; and Sag Harbor, Long Island. By far the largest number sailed from New Bedford, but Nantucket continued to host a fleet, even when they needed to use "camels," or floating drydocks, to get over the sandbar that formed at the mouth of the harbor.

Thomas Welcome Roys

Thomas Welcome Roys (c. 1816 - d. 1877) was an American whaleman. He was significant in the history of whaling in that he discovered the Western Arctic bowhead whale population and developed and patented whaling rockets in order to hunt the faste ...

, in the Sag Harbor bark

Bark may refer to:

* Bark (botany), an outer layer of a woody plant such as a tree or stick

* Bark (sound), a vocalization of some animals (which is commonly the dog)

Places

* Bark, Germany

* Bark, Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship, Poland

Arts, ...

''Superior'', sailed through the Bering Strait on 23 July 1848, and discovered an abundance of "new fangled monsters," or later to be known as bowhead whale

The bowhead whale (''Balaena mysticetus'') is a species of baleen whale belonging to the family Balaenidae and the only living representative of the genus ''Balaena''. They are the only baleen whale endemic to the Arctic and subarctic waters, ...

s. The following season fifty whalers—46 from New England, two from Germany, and two from France—sailed to the Bering Strait region on the report from this single ship. In terms of number of vessels and whales killed, the peak was reached in 1852, when 220 ships killed 2,682 bowheads. Catches declined, and the fleet shifted to the Sea of Okhotsk

The Sea of Okhotsk ( rus, Охо́тское мо́ре, Ohótskoye móre ; ja, オホーツク海, Ohōtsuku-kai) is a marginal sea of the western Pacific Ocean. It is located between Russia's Kamchatka Peninsula on the east, the Kuril Islands ...

in 1853–1854. Whaling there peaked in 1855–1857, and once that area began to decline in 1858–1860, they returned to the Bering Strait region.

Peak

The American whaling fleet, after steadily growing for 50 years, reached its all-time peak of 199,000 tons in 1858. Just two years later, in 1860, just before the Civil War, the fleet had dropped to 167,000 tons. The war cut into whaling temporarily, but only 105,000 whaling tons returned to sea in 1866, the first full year of peace, and that number dwindled until only 39 American ships set out to hunt whales in 1876.

During the winter, some of these same vessels would make their way to the lagoons of

The American whaling fleet, after steadily growing for 50 years, reached its all-time peak of 199,000 tons in 1858. Just two years later, in 1860, just before the Civil War, the fleet had dropped to 167,000 tons. The war cut into whaling temporarily, but only 105,000 whaling tons returned to sea in 1866, the first full year of peace, and that number dwindled until only 39 American ships set out to hunt whales in 1876.

During the winter, some of these same vessels would make their way to the lagoons of Baja California

Baja California (; 'Lower California'), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Baja California ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Baja California), is a state in Mexico. It is the northernmost and westernmost of the 32 federal entities of Mex ...

. The peak began in 1855, commencing the period of lagoon whaling known as the "bonanza period", when whaleboats were crisscrossing through the lagoons, being pulled by enraged whales, passing by calves that had lost their mothers and other ships' crews hunting whales. Less than twenty years later, in 1874, the lagoon fishery was abandoned entirely, due to several years of poor catches.

Several New England ships were lost during the 1860s and 1870s. During the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, Confederate raiders such as the , , and captured or burned 46 ships, while the United States purchased forty of the fleet's oldest hulls. Known as the Stone Fleet

The Stone Fleet consisted of a fleet of aging ships (mostly whaleships) purchased in New Bedford and other New England ports, loaded with stone, and sailed south during the American Civil War by the Union Navy for use as blockships. They were to ...

, these ships were purchased to sink in Charleston

Charleston most commonly refers to:

* Charleston, South Carolina

* Charleston, West Virginia, the state capital

* Charleston (dance)

Charleston may also refer to:

Places Australia

* Charleston, South Australia

Canada

* Charleston, Newfoundlan ...

and Savannah

A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland-grassland (i.e. grassy woodland) ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the Canopy (forest), canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to rea ...

harbors in a failed attempt to blockade those ports. Thirty-three of the 40 whalers that comprised the Arctic

The Arctic ( or ) is a polar regions of Earth, polar region located at the northernmost part of Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean, adjacent seas, and parts of Canada (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut), Danish Realm (Greenla ...

fleet were lost near Point Belcher and Wainwright Inlet in the Whaling Disaster of 1871

The Whaling Disaster of 1871 was an incident off the northern Alaskan coast in which a fleet of 33 American whaling ships were trapped in the Arctic ice in late 1871 and subsequently abandoned. It dealt a serious blow to the American whaling indu ...

, while another 12 ships were lost in 1876.

The use of steam, the high prices for

The use of steam, the high prices for whalebone

Baleen is a filter-feeding system inside the mouths of baleen whales. To use baleen, the whale first opens its mouth underwater to take in water. The whale then pushes the water out, and animals such as krill are filtered by the baleen and re ...

, and the proximity of the whaling grounds brought the rise of San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

as a dominant whaling port in the 1880s. By 1893, it had 33 whaleships, of which 22 were steamers. At first, the steamers only cruised during the summer months, but with the discovery of bowheads near the Mackenzie River Delta in 1888–1889 by Joe Tuckfield, ships begin to overwinter at Herschel Island

Herschel Island (french: Île d'Herschel; Inuit languages: ''Qikiqtaruk'') is an island in the Beaufort Sea (part of the Arctic Ocean), which lies off the coast of Yukon in Canada, of which it is administratively a part. It is Yukon's only o ...

, off the Yukon coast.

The first to go to Herschel was in 1890–1891, and by 1894–1895 there were fifteen such ships overwintering in Pauline Cove. During the peak of the settlement, 1894–1896, about 1,000 persons went to the island, comprising a polyglot community of Nunatarmiuts, Inuit caribou hunters, originating from the Brooks Range; Kogmullicks, Inuit who inhabited the coastal regions of the Mackenzie River delta; Itkillicks, Rat Indians, from the forested regions south; Alaskan and Siberian ships' natives, whaling crews and their families; and beachcombers

''The Beachcombers'' is a Canadian comedy-drama television series that ran on CBC Television from October 1, 1972, to December 12, 1990. With over 350 episodes, it is one of the longest-running dramatic series ever made for English-language Canad ...

, the few whalemen whose tour of duty had ended, but chose to stay at the island.

Ships continued to overwinter at Herschel into the 20th century, but by that time they focused more on trading with the natives than on whaling. By 1909 there were only three whaleships left in the

Ships continued to overwinter at Herschel into the 20th century, but by that time they focused more on trading with the natives than on whaling. By 1909 there were only three whaleships left in the Arctic

The Arctic ( or ) is a polar regions of Earth, polar region located at the northernmost part of Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean, adjacent seas, and parts of Canada (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut), Danish Realm (Greenla ...

fleet, with the last bowhead being killed commercially in 1921.

Decline

New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

whaling declined due to the mid-nineteenth century industrial revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

and the increased use of alternative fluids like coal oil

Coal oil is a shale oil obtained from the destructive distillation of cannel coal, mineral wax, or bituminous shale, once used widely for illumination.

Chemically similar to the more refined, petroleum-derived kerosene, it consists mainly of se ...

and turpentine

Turpentine (which is also called spirit of turpentine, oil of turpentine, terebenthene, terebinthine and (colloquially) turps) is a fluid obtained by the distillation of resin harvested from living trees, mainly pines. Mainly used as a special ...

. By 1895, the New England whaling fleet had dwindled to 51 vessels, with only four ports regularly sending out ships. They were New Bedford

New Bedford (Massachusett: ) is a city in Bristol County, Massachusetts. It is located on the Acushnet River in what is known as the South Coast region. Up through the 17th century, the area was the territory of the Wampanoag Native American pe ...

, Provincetown

Provincetown is a New England town located at the extreme tip of Cape Cod in Barnstable County, Massachusetts, in the United States. A small coastal resort town with a year-round population of 3,664 as of the 2020 United States Census, Provincet ...

, San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

, and Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

. Boston left the trade in 1903, with San Francisco leaving in 1921. Only New Bedford continued on into the trade, sending out its last whaler, the ''John R. Mantra'', in 1927.

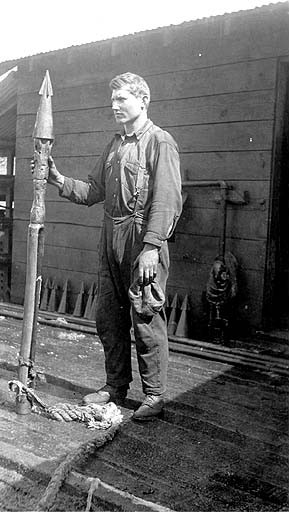

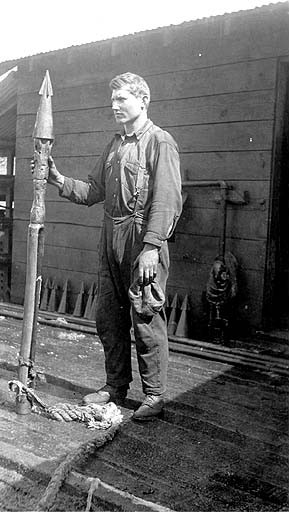

Modern whaling

Whaling stations operated in Alaska and on the Canadian west coast. American Pacific Whaling Company, with headquarters inVictoria, British Columbia

Victoria is the capital city of the Canadian province of British Columbia, on the southern tip of Vancouver Island off Canada's Pacific coast. The city has a population of 91,867, and the Greater Victoria area has a population of 397,237. Th ...

, operated ships and a plant in 1912 at Gray's Harbor, Washington with catcher ships ranging from the Canada–United States border south to Cape Blanco in Oregon. The economic success and profits were so high that the company decided to build new ships in 1913. At least one of the company's ships, is shown as active 1930 through 1945 with American Pacific Whaling Company in Lloyd's Register. Another company, West Coast Whaling Company, was organized in 1912 to operate out of Trinidad, California

Trinidad (Spanish for "Trinity"; Yurok: ''Chuerey'') is a seaside city in Humboldt County, located on the Pacific Ocean north of the Arcata-Eureka Airport and north of the college town of Arcata. Trinidad is noted for its coastline with ten ...

.

While whaling came to an end on the east coast in the early 20th-century, it lingered and even rebounded briefly on the west coast. A small shore-based whaling operation existed in San Francisco through the early 1970s. During the early 1960s, a small whaling fishery was developed near Astoria, Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

as a collaboration between a local fishing family and the processing firm BioProducts. A single-ship operation was successful during the early 1960s, making a profit through sales of meat to local mink farms and whale oil to NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research.

NASA was established in 1958, succeeding t ...

. As synthetic oils came onto the markets, the demand for scientific grade whale oil was diminished and the operation came to a close about 1965. The whale processor has since refocused their operations on processing of other seafood oils and continues to operate today as BioOregon Protein.

Federal ban

In 1971, U.S. Congress passed the Pelly Amendment to ensure that residents of the United States would comply with regulations issued by an international fishery conservation program, including the International Whaling Commission. In 1972, Congress passed the Marine Mammal Protection Act, which makes it illegal for any person residing in the United States to kill, hunt, injure or harass all species of marine mammals, regardless of their population status. Whales who are considered to be endangered are also protected by the 1973 Endangered Species Act. The 1979 Packwood-Magnuson Amendment to the Fishery Conservation and Management Act of 1976 extended the federal whaling ban to foreigners who chose to come within 200 miles of the U.S. coastline.Native whaling in modern times

In Alaska, bowhead whale and beluga whale hunts are regulated by the

In Alaska, bowhead whale and beluga whale hunts are regulated by the NMFS

The National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), informally known as NOAA Fisheries, is a United States federal agency within the U.S. Department of Commerce's National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) that is responsible for the stew ...

. In 2016 Alaskans caught 59 bowhead, two minke and one sperm whale; the latter two species were not authorized, though no one was prosecuted. IWC does not count belugas; Alaskans caught 326 belugas in 2015, monitored by the Alaska Beluga Whale Committee. The annual catch of beluga ranges between 300 and 500 per year and bowheads between 40 and 70 per year.

The 1855 Treaty of Neah Bay

The Makah (; Klallam: ''màq̓áʔa'')Renker, Ann M., and Gunther, Erna (1990). "Makah". In "Northwest Coast", ed. Wayne Suttles. Vol. 7 of ''Handbook of North American Indians'', ed. William C. Sturtevant. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institu ...

let Makah

The Makah (; Klallam: ''màq̓áʔa'')Renker, Ann M., and Gunther, Erna (1990). "Makah". In "Northwest Coast", ed. Wayne Suttles. Vol. 7 of ''Handbook of North American Indians'', ed. William C. Sturtevant. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institut ...

in Washington State hunt whales. Low stocks stopped them in the 1920s but recovered by the 1980s. In 1996 they sought an International Whaling Commission

The International Whaling Commission (IWC) is a specialised regional fishery management organisation, established under the terms of the 1946 International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling (ICRW) to "provide for the proper conservation of ...

quota for nutritional subsistence, also known as aboriginal whaling

Indigenous whaling is the hunting of whales by indigenous peoples recognised by either IWC (International Whaling Commission) or the hunting is considered as part of indigenous activity by the country. It is permitted under international regu ...

. The industrial whaling countries of Japan and Norway supported them, but most countries did not, since Makah had lived without hunting for 70 years. In 1997 they argued whaling was "cultural 'glue' that holds the Tribe together" and received a quota, though countries worried about the precedent for other old whaling societies. In 2001, the United States government once again overturned its previous ruling and declared it illegal for the Makah to hunt whales. Makah, the United States, and environmental groups are still fighting legal battles.

Recruitment of whalers

According to Frances Diane Robotti, there were three types of whalemen: those who hoped to own their own whaleship someday, those who were seeking adventure, and those who were running from something on shore. Generally only those who hoped to make a career of whaling went out more than once.

Since a whaleman's pay was based on his "lay", or share of the catch, he sometimes returned from a long voyage to find himself paid next to nothing, or even owing money to his employers. Even a bonanza voyage paid the ordinary crewman less than if he had served in the merchant fleet. The lay system was a gamble and sailors were never ensured decent wages. Richard Boyenton of the "Bengal" only earned six and a quarter cents after five months at sea, but occasionally sailors got lucky and brought home a significant amount of money after just a couple of voyages. More commonly sailors would earn very little after years at sea. Ships that returned to port less than full of oil were called "broken voyages" while ships that came home overflowing were praised. The ''Loper'' returned to Nantucket with its deck and hold chock full of casks of oil while ships like the ''Brewster'' prioritized oil so significantly that they threw food and water overboard to make more room for oil.

Going to sea was a young man's adventure, particularly when he wound up in the South Sea paradises of the

According to Frances Diane Robotti, there were three types of whalemen: those who hoped to own their own whaleship someday, those who were seeking adventure, and those who were running from something on shore. Generally only those who hoped to make a career of whaling went out more than once.

Since a whaleman's pay was based on his "lay", or share of the catch, he sometimes returned from a long voyage to find himself paid next to nothing, or even owing money to his employers. Even a bonanza voyage paid the ordinary crewman less than if he had served in the merchant fleet. The lay system was a gamble and sailors were never ensured decent wages. Richard Boyenton of the "Bengal" only earned six and a quarter cents after five months at sea, but occasionally sailors got lucky and brought home a significant amount of money after just a couple of voyages. More commonly sailors would earn very little after years at sea. Ships that returned to port less than full of oil were called "broken voyages" while ships that came home overflowing were praised. The ''Loper'' returned to Nantucket with its deck and hold chock full of casks of oil while ships like the ''Brewster'' prioritized oil so significantly that they threw food and water overboard to make more room for oil.

Going to sea was a young man's adventure, particularly when he wound up in the South Sea paradises of the Sandwich Islands

The Hawaiian Islands ( haw, Nā Mokupuni o Hawai‘i) are an archipelago of eight major islands, several atolls, and numerous smaller islets in the North Pacific Ocean, extending some from the island of Hawaii in the south to northernmost Kur ...

, Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian ; ; previously also known as Otaheite) is the largest island of the Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia. It is located in the central part of the Pacific Ocean and the nearest major landmass is Austr ...

, or the Marquesas Islands

The Marquesas Islands (; french: Îles Marquises or ' or '; Marquesan: ' ( North Marquesan) and ' ( South Marquesan), both meaning "the land of men") are a group of volcanic islands in French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of France in th ...

, where a young American man might find himself surrounded by young women ready to freely offer him their charms, something he was unlikely to experience at home. Many, including Herman Melville

Herman Melville (Name change, born Melvill; August 1, 1819 – September 28, 1891) was an American people, American novelist, short story writer, and poet of the American Renaissance (literature), American Renaissance period. Among his bes ...

, jumped ship, apparently without repercussions. After his romantic interlude among the Typees on Nuku Hiva

Nuku Hiva (sometimes spelled Nukahiva or Nukuhiva) is the largest of the Marquesas Islands in French Polynesia, an overseas country of France in the Pacific Ocean. It was formerly also known as ''Île Marchand'' and ''Madison Island''.

Herman M ...

in the Marquesas, Melville joined another whaler that took him to Hawaii, from where he sailed for home as a crewman on . Along with Robert Louis Stevenson

Robert Louis Stevenson (born Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson; 13 November 1850 – 3 December 1894) was a Scottish novelist, essayist, poet and travel writer. He is best known for works such as ''Treasure Island'', ''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll a ...

, Paul Gauguin

Eugène Henri Paul Gauguin (, ; ; 7 June 1848 – 8 May 1903) was a French Post-Impressionist artist. Unappreciated until after his death, Gauguin is now recognized for his experimental use of colour and Synthetist style that were distinct fr ...

, and others, Melville cultivated the image of the Pacific islands as romantic paradises. The California Gold Rush

The California Gold Rush (1848–1855) was a gold rush that began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The news of gold brought approximately 300,000 people to California fro ...

offered young men an adventure to California, for free if they signed on as a whaleman. Many whalemen (including captains and officers) abandoned the crew in San Francisco there, leaving abundant ships deserted in the bay.

Scrimshaw art

A large number of crewmen on American, British, and other countries vessels that participated in whaling in the 19th century created

A large number of crewmen on American, British, and other countries vessels that participated in whaling in the 19th century created scrimshaw

Scrimshaw is scrollwork, engravings, and carvings done in bone or ivory. Typically it refers to the artwork created by whalers, engraved on the byproducts of whales, such as bones or cartilage. It is most commonly made out of the bones and teeth ...

. Scrimshaw is the practice of drawing on whale teeth or other forms of ivory

Ivory is a hard, white material from the tusks (traditionally from elephants) and teeth of animals, that consists mainly of dentine, one of the physical structures of teeth and tusks. The chemical structure of the teeth and tusks of mammals is ...

with various tools, typically sailor's knives or other sharp instruments. These images were then coated with ink so that the drawing would appear more noticeable on the whale tooth. It is believed that some instruments used by sailors to perform scrimshaw included surgical tools, as with the work done by whaling surgeon William Lewis Roderick. Other forms of ivory included a whale's panbone, walrus ivory

The walrus (''Odobenus rosmarus'') is a large flippered marine mammal with a discontinuous distribution about the North Pole in the Arctic Ocean and subarctic seas of the Northern Hemisphere. The walrus is the only living species in the fami ...

, and elephant ivory. Of course, the most common scrimshaw during the whaling period of the 19th century was made from whale parts.

Other forms of scrimshaw included whalebone fids (rope splicer), bodkins (needle), swifts (yarn holding equipment) and sailors' canes. The time when most scrimshaw in the 19th century was produced coincided with the heyday of the whaling industry which occurred between 1840–1860. More than 95% of all antique scrimshaw whale teeth known were done by anonymous artists. Some of the better known antique scrimshaw artists include Frederick Myrick and Edward Burdett, who were two of the first scrimshanders to ever sign and date their work. Several museums now house outstanding collections of antique scrimshaw and one of the best being the New Bedford Whaling Museum

The New Bedford Whaling Museum is a museum in New Bedford, Massachusetts, United States that focuses on the history, science, art, and culture of the international whaling industry, and the "Old Dartmouth" region (now the city of New Bedford and ...

in Massachusetts.

See also

* ''Charles W. Morgan'' *Cold Spring Harbor Whaling Museum

The Whaling Museum & Education Center, formerly known as The Whaling Museum, is a maritime museum located in Cold Spring Harbor, New York dedicated to the local history, the maritime heritage of Long Island and its impact of the whaling indust ...

* Mystic Seaport

Mystic Seaport Museum or Mystic Seaport: The Museum of America and the Sea in Mystic, Connecticut is the largest maritime museum in the United States. It is notable for its collection of sailing ships and boats and for the re-creation of the craf ...

* New Bedford Whaling Museum

The New Bedford Whaling Museum is a museum in New Bedford, Massachusetts, United States that focuses on the history, science, art, and culture of the international whaling industry, and the "Old Dartmouth" region (now the city of New Bedford and ...

* New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park

New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park (NBWNHP) is a United States National Historical Park in New Bedford, Massachusetts, and is maintained by the National Park Service (NPS). The park commemorates the heritage of the world's preeminent w ...

* Whaling in the United Kingdom

Commercial whaling in Britain began late in the 16th century and continued after the 1801 formation of the United Kingdom and intermittently until the middle of the 20th century.

The trade was broadly divided into two branches. The northern fisher ...

Footnotes

Bibliography

* * * * * * *Further reading

* Busch, Briton Cooper (2004)''Whaling Will Never Do for Me: The American Whaleman in the Nineteenth Century''

The University Press of Kentucky. . * * George, G. D. and R. G. Bosworth (April 1988)

''Use of Fish and Wildlife by Residents of Angoon, Admiralty Island, Alaska''

* *

"Race Revive Old Whaling Days of Old" ''Popular Mechanics'', November 1930

"A Brief History of Pacific Coast Whaling"

by Nicholas J. Lee * Federal Writers' Project of the Works Progress Administration of Massachusetts (1938).

Whaling Masters: Voyages, 1731–1925

'. New Bedford, Mass.: Published by the Old Dartmouth Historical Society.

External links

''Into the Deep: America, Whaling & The World''

a 2010 documentary film by

Ric Burns

Ric Burns (Eric Burns, born 1955) is an American documentary filmmaker and writer. He has written, directed and produced historical documentaries since the 1990s, beginning with his collaboration on the celebrated PBS series '' The Civil War'' (1 ...

for ''American Experience

''American Experience'' is a television program airing on the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) in the United States. The program airs documentaries, many of which have won awards, about important or interesting events and people in American his ...

''

The Papers of Leander Owens, Whaling Captain

at Dartmouth College Library

Frederick W. Maurer "Belvedere" Narrative (1911-1912) Manuscript

at Dartmouth College Library

Francis Brown Collection on the Whaler 'Canada'

at Dartmouth College Library {{Whaling, state=collapsed Economic history of the United States Maritime history of the United States Natural history of the United States Cape Verdean American history