Western University (Kansas) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Western University (Kansas) (18651943) was a

The first classes of what became Western University were started by Eben Blachley in his home in 1862, who taught the children of

The first classes of what became Western University were started by Eben Blachley in his home in 1862, who taught the children of  In about 1911, students, faculty, and churches raised $2,000 to erect a statue of abolitionist

In about 1911, students, faculty, and churches raised $2,000 to erect a statue of abolitionist

''Kansas City Star'', February 23, 2008, accessed January 12, 2009 The late historian and Western alumnus Orrin McKinley Murray Sr. wrote about the Jackson Jubilee Singers in his 1960 book ''The Rise and Fall of Western University'':

The Great Depression reduced available financial support, and the university faced increasing competition to attract students. Finally Western University closed in 1943.

Nothing but cornerstones of the earliest two halls still exist at the townsite. Some buildings were lost to fire, others to demolition as the sites were redeveloped. The last historic structures remaining were three faculty houses, which were demolished near the end of the 20th century.

The Great Depression reduced available financial support, and the university faced increasing competition to attract students. Finally Western University closed in 1943.

Nothing but cornerstones of the earliest two halls still exist at the townsite. Some buildings were lost to fire, others to demolition as the sites were redeveloped. The last historic structures remaining were three faculty houses, which were demolished near the end of the 20th century."Virtual Tour: Western University", ''Quindaro, Kansas on the Underground Railroad''

, Online exhibit, Kansas City, Kansas Library, 2000, accessed December 20, 2008 The statue of John Brown survives, and has had a little memorial plaza built around it.

''Western University Online Collection''

State Library of Kansas KGI Online Library

Online exhibit, Kansas City, Kansas Library, 2000

{{authority control Historically black schools Historically black universities and colleges in the United States Music schools in Kansas History of Kansas Abolitionism in the United States Defunct universities and colleges in Kansas 1943 disestablishments in Kansas 1865 establishments in Kansas Educational institutions established in 1865 Educational institutions disestablished in 1943

historically black college

Historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) are institutions of higher education in the United States that were established before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 with the intention of primarily serving the African-American community. Mo ...

(HBCU) established in 1865 (after the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

) as the Quindaro Freedman's School at Quindaro, Kansas

Quindaro Townsite is a former settlement, then ghost town, and now an archaeological district. It is around North 27th Street and the Missouri Pacific Railroad tracks in Kansas City, Kansas. It was placed on the National Register of Historic Pla ...

, United States. The earliest school for African Americans

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

west of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

, it was the only one to operate in the state of Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the ...

.

In the first three decades of the 20th century, its music school was recognized nationally as one of the best. The Jackson Jubilee Singers toured from 1907 to 1940, and appeared on the Chautauqua

Chautauqua ( ) was an adult education and social movement in the United States, highly popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Chautauqua assemblies expanded and spread throughout rural America until the mid-1920s. The Chautauqua bro ...

circuit. Among the university's most notable alumni were several women who were influential music pioneers in the early 20th century, including Eva Jessye

Eva Jessye (January 20, 1895 – February 21, 1992) was an American conductor who was the first black woman to receive international distinction as a professional choral conductor. She is notable as a choral conductor during the Harlem Renaissa ...

, who created her own choir and collaborated with major artists such as Virgil Thomson

Virgil Thomson (November 25, 1896 – September 30, 1989) was an American composer and critic. He was instrumental in the development of the "American Sound" in classical music. He has been described as a modernist, a neoromantic, a neoclassic ...

and George Gershwin

George Gershwin (; born Jacob Gershwine; September 26, 1898 – July 11, 1937) was an American composer and pianist whose compositions spanned popular, jazz and classical genres. Among his best-known works are the orchestral compositions ' ...

in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

. Nora Douglas Holt was a composer, music critic and performer who toured in Europe as well as the United States. Etta Moten Barnett

Etta Moten Barnett (November 5, 1901 – January 2, 2004) was an American actress and contralto vocalist, who was identified with her signature role of "Bess" in ''Porgy and Bess''. She created new roles for African-American women on stage ...

became known for singing the lead in ''Porgy and Bess

''Porgy and Bess'' () is an English-language opera by American composer George Gershwin, with a libretto written by author DuBose Heyward and lyricist Ira Gershwin. It was adapted from Dorothy Heyward and DuBose Heyward's play '' Porgy'', itse ...

'' in revival and on tour.

Expanded around the start of the 20th century with an industrial department modeled after Booker T. Washington

Booker Taliaferro Washington (April 5, 1856November 14, 1915) was an American educator, author, orator, and adviser to several presidents of the United States. Between 1890 and 1915, Washington was the dominant leader in the African-American c ...

's Tuskegee Institute

Tuskegee University (Tuskegee or TU), formerly known as the Tuskegee Institute, is a private, historically black land-grant university in Tuskegee, Alabama. It was founded on Independence Day in 1881 by the state legislature.

The campus was de ...

, the university served African Americans for several generations. It struggled financially during the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

, as did many colleges, and finally closed in 1943. None of its buildings are still standing.

History

The first classes of what became Western University were started by Eben Blachley in his home in 1862, who taught the children of

The first classes of what became Western University were started by Eben Blachley in his home in 1862, who taught the children of freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), abolitionism, emancipation (gra ...

. Most of the homesites of Quindaro were on the bluff; the port's commercial district was in the bottomland near the level of the Missouri River below the bluffs. The area of the Quindaro settlement was annexed by Kansas City in the early 20th century.

The town had been started in 1856 by abolitionists

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

, Wyandot

Wyandot may refer to:

Native American ethnography

* Wyandot people, also known as the Huron

* Wyandot language

* Wyandot religion

Places

* Wyandot, Ohio, an unincorporated community

* Wyandot County, Ohio

* Camp Wyandot, a Camp Fire Boys and ...

, free blacks, and settlers from the New England Emigrant Aid Company

The New England Emigrant Aid Company (originally the Massachusetts Emigrant Aid Company) was a transportation company founded in Boston, Massachusetts by activist Eli Thayer in the wake of the Kansas–Nebraska Act, which allowed the population of ...

. The latter had come from Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

and other northeast states to help Kansas become a free rather than slave state — a question to be settled by its voters. They started construction of buildings in January 1857 and a hundred were built in the first year. As a stop on the Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was a network of clandestine routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early- to mid-19th century. It was used by enslaved African Americans primarily to escape into free states and Canada. T ...

, Quindaro absorbed or assisted fugitive slaves

In the United States, fugitive slaves or runaway slaves were terms used in the 18th and 19th century to describe people who fled slavery. The term also refers to the federal Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850. Such people are also called free ...

before the Civil War and many contraband

Contraband (from Medieval French ''contrebande'' "smuggling") refers to any item that, relating to its nature, is illegal to be possessed or sold. It is used for goods that by their nature are considered too dangerous or offensive in the eyes o ...

s (fugitive slaves behind Union lines), especially from Missouri, during the war.

After the war, a committee of white men in the community, former abolitionists, organized a school to educate freedmen who had resettled in Quindaro and the Kansas City area. In 1865 the committee registered their county charter for what they called Quindaro Freedman's School. In 1867 the state legislature approved funds for the school.

In 1872 the state increased funding to establish a four-year normal school curriculum for the training of teachers. Charles Henry Langston

Charles Henry Langston (1817–1892) was an American abolitionist and political activist who was active in Ohio and later in Kansas, during and after the American Civil War, where he worked for black suffrage and other civil rights. He was a spoke ...

, a prominent activist and politician (and the future grandfather of poet Langston Hughes

James Mercer Langston Hughes (February 1, 1901 – May 22, 1967) was an American poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, and columnist from Joplin, Missouri. One of the earliest innovators of the literary art form called jazz poetry, Hug ...

), was named principal of the normal school. Freedmen and blacks free before the war believed that education was key for advancement of their race.

State financial difficulties caused it to reduce support following the Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the "Lon ...

, and the school had to reduce its enrollment. Blachley continued to support it, bequeathing of land in the 1870s to help support the college that had developed from his first classes. In the 1880s, Exodusters

Exodusters was a name given to African Americans who Human migration, migrated from U.S. state, states along the Mississippi River to Kansas in the late nineteenth century, as part of the Exoduster Movement or Exodus of 1879. It was the first Hum ...

and other migrants added significantly to the African-American population in Kansas. The college began to be active again.

In the late 19th century, the African Methodist Episcopal

The African Methodist Episcopal Church, usually called the AME Church or AME, is a predominantly African American Methodist denomination. It adheres to Wesleyan-Arminian theology and has a connexional polity. The African Methodist Episcopal ...

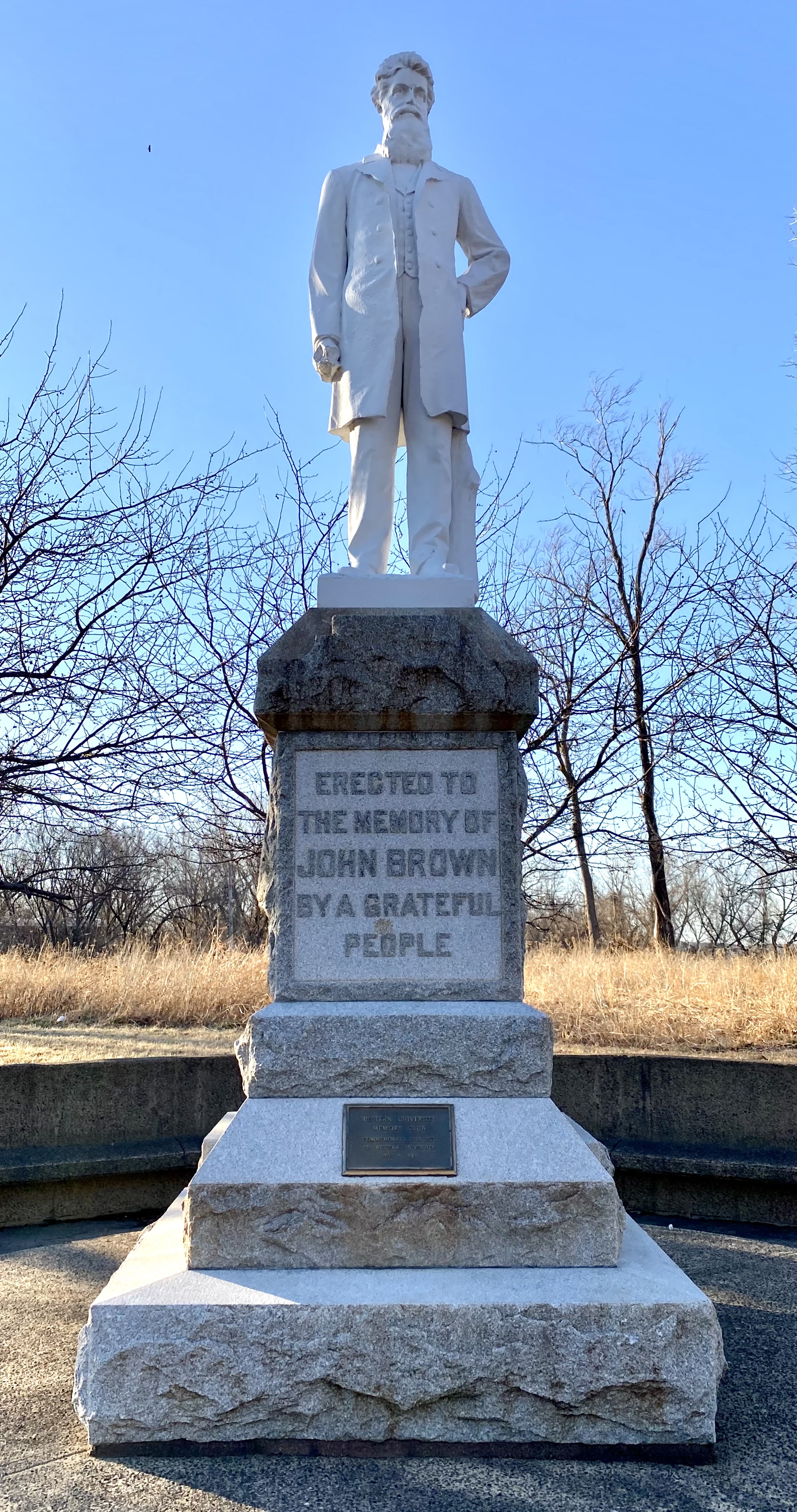

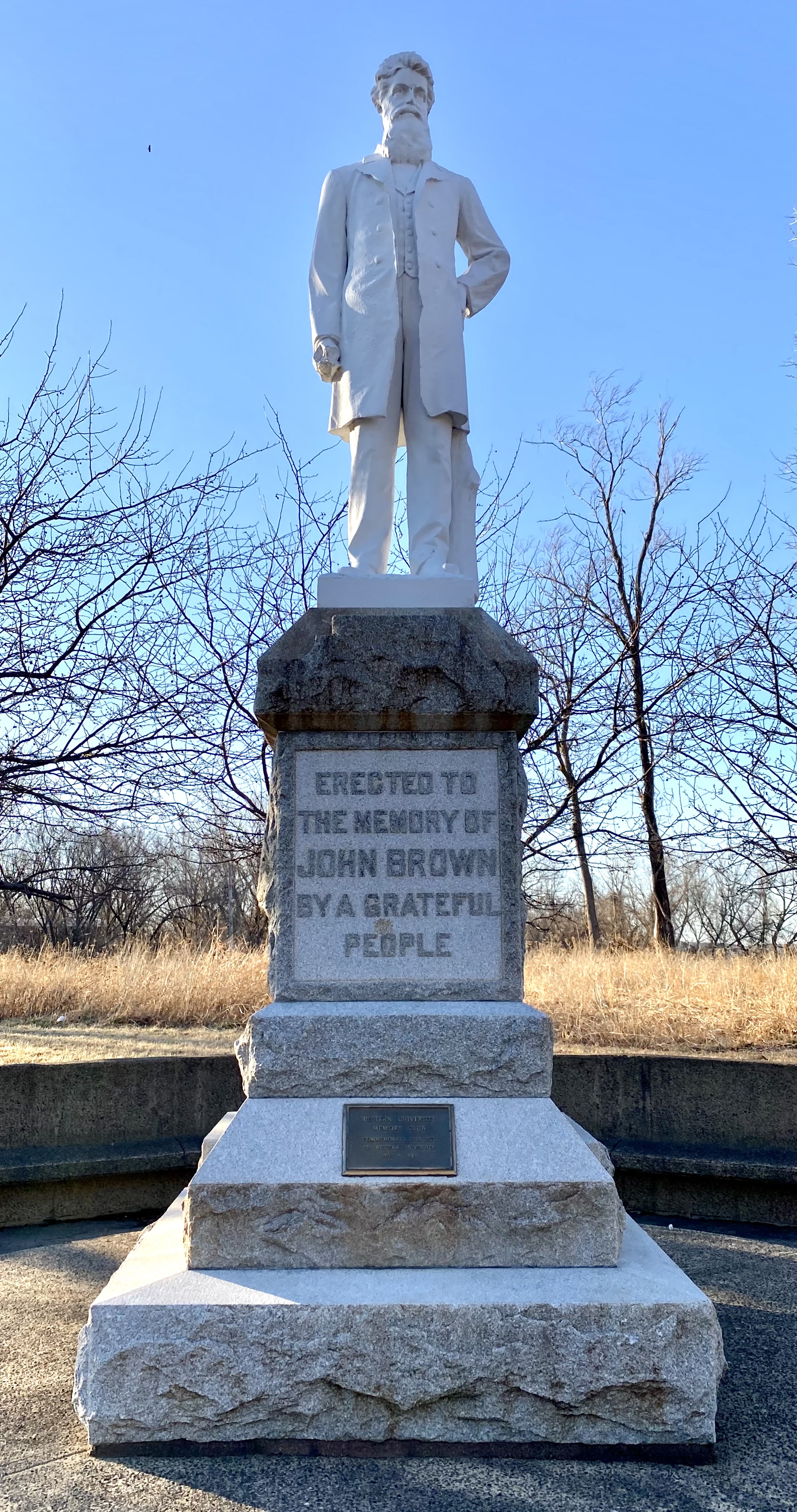

(AME) Conference began to help provide financial support for the school. Quindaro added a theological course and constructed Ward Hall in 1891 to accommodate it; the hall was named after a bishop of the AME Church. In 1890 the expanded college's first African-American president was appointed. In about 1911, students, faculty, and churches raised $2,000 to erect a statue of abolitionist

In about 1911, students, faculty, and churches raised $2,000 to erect a statue of abolitionist John Brown John Brown most often refers to:

*John Brown (abolitionist) (1800–1859), American who led an anti-slavery raid in Harpers Ferry, Virginia in 1859

John Brown or Johnny Brown may also refer to:

Academia

* John Brown (educator) (1763–1842), Ir ...

. That statue, although missing its nose and having other damage, still stands at the location of the campus.

Programs

In 1896William Tecumseh Vernon

William Tecumseh Vernon (July 11, 1871 – July 25, 1944) was an American educator, minister and bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal Church who served as president of Western University beginning in 1896 and Register of the Treasury from 190 ...

, a young AME minister, was appointed as president. He worked to increase state funding. In 1899 he gained legislative approval and financial support to add industrial education to the college, which prompted building numerous structures for the new classes, as well as dormitories. Industrial courses were on the model of Booker T. Washington

Booker Taliaferro Washington (April 5, 1856November 14, 1915) was an American educator, author, orator, and adviser to several presidents of the United States. Between 1890 and 1915, Washington was the dominant leader in the African-American c ...

's Tuskegee Institute

Tuskegee University (Tuskegee or TU), formerly known as the Tuskegee Institute, is a private, historically black land-grant university in Tuskegee, Alabama. It was founded on Independence Day in 1881 by the state legislature.

The campus was de ...

: commercial business courses, drafting, printing, carpentry, and tailoring; later, blacksmithing and wheelwrighting were added to prepare students with desired skills for making a living. The campus was expanded with training buildings to house livestock, and another for a laundry. Later a building was added for teaching auto mechanics and repair. A central steam plant was added, as were additional dormitories. From 1916 to 1918, Inman E. Page

Inman E. Page (December 29, 1853 - December 21, 1935) was a Baptist leader and educator in Oklahoma and Missouri. He was president of four schools: the Lincoln Institute, Langston University, Western University, and Roger Williams University and ...

was president.

The music school was developed after 1903 by Robert G. Jackson, who created the Jackson Jubilee Singers. Fannie De Grasse Black was instructor of pipe organ. From 1907 to 1940, the group was extremely popular. It toured the United States and Canada, performing on the Chautaqua circuit, where it helped create goodwill and raise money for the college through fundraising. In addition, the group's studies and performances helped preserve the spirituals of African-American tradition.Paul Wenske, "Western University at Quindaro championed the music of freedom"''Kansas City Star'', February 23, 2008, accessed January 12, 2009 The late historian and Western alumnus Orrin McKinley Murray Sr. wrote about the Jackson Jubilee Singers in his 1960 book ''The Rise and Fall of Western University'':

So great was their success in rendering spirituals and the advertising of the music department of Western University, that all young people who had any type of musical ambition decided to go to Western University at Quindaro.The music school's most famous alumni were women who became influential pioneers of the 20th century in composition and music performance, including choral conducting. They included Nora Douglas Holt,

Eva Jessye

Eva Jessye (January 20, 1895 – February 21, 1992) was an American conductor who was the first black woman to receive international distinction as a professional choral conductor. She is notable as a choral conductor during the Harlem Renaissa ...

, and Etta Moten Barnett

Etta Moten Barnett (November 5, 1901 – January 2, 2004) was an American actress and contralto vocalist, who was identified with her signature role of "Bess" in ''Porgy and Bess''. She created new roles for African-American women on stage ...

. Nora Holt was a composer, music critic and performer in the US and Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

. Eva Jessye went to New York and founded her own choir, which was featured in her collaboration with composer Virgil Thomson

Virgil Thomson (November 25, 1896 – September 30, 1989) was an American composer and critic. He was instrumental in the development of the "American Sound" in classical music. He has been described as a modernist, a neoromantic, a neoclassic ...

and writer Gertrude Stein

Gertrude Stein (February 3, 1874 – July 27, 1946) was an American novelist, poet, playwright, and art collector. Born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in the Allegheny West neighborhood and raised in Oakland, California, Stein moved to Paris ...

on '' Four Saints in Three Acts.'' She was selected by George Gershwin

George Gershwin (; born Jacob Gershwine; September 26, 1898 – July 11, 1937) was an American composer and pianist whose compositions spanned popular, jazz and classical genres. Among his best-known works are the orchestral compositions ' ...

as his choral director for his opera ''Porgy and Bess

''Porgy and Bess'' () is an English-language opera by American composer George Gershwin, with a libretto written by author DuBose Heyward and lyricist Ira Gershwin. It was adapted from Dorothy Heyward and DuBose Heyward's play '' Porgy'', itse ...

''. . Moten Barnett was a singer who made "Bess," of ''Porgy and Bess,'' a signature role after performing it in the Broadway revival and on tour. Other early alumni of the school included composer and music educator L. Viola Kinney.

In the early 20th century, Western University was lauded for its outstanding music program.

Western University at Quindaro, Kansas, was probably the earliest black school west of the Mississippi and the best black musical training center in the Midwest for almost thirty years during the 1900s through the 1920s.In 1915, the university's monthly newspaper ''University Pen Point'' was first published.

Closing

The Great Depression reduced available financial support, and the university faced increasing competition to attract students. Finally Western University closed in 1943.

Nothing but cornerstones of the earliest two halls still exist at the townsite. Some buildings were lost to fire, others to demolition as the sites were redeveloped. The last historic structures remaining were three faculty houses, which were demolished near the end of the 20th century.

The Great Depression reduced available financial support, and the university faced increasing competition to attract students. Finally Western University closed in 1943.

Nothing but cornerstones of the earliest two halls still exist at the townsite. Some buildings were lost to fire, others to demolition as the sites were redeveloped. The last historic structures remaining were three faculty houses, which were demolished near the end of the 20th century., Online exhibit, Kansas City, Kansas Library, 2000, accessed December 20, 2008 The statue of John Brown survives, and has had a little memorial plaza built around it.

References

*Murray, Orrin McKinley Sr. (1960) ''The Rise and Fall of Western University''. Kansas City, KS: Privately printed, 1974. *Smith, Thaddeus T. ''Western University: A Ghost College In Kansas'', Unpublished Master of Arts thesis, Pittsburg State College; Pittsburg, Kansas: 1966 *External links

''Western University Online Collection''

State Library of Kansas KGI Online Library

Online exhibit, Kansas City, Kansas Library, 2000

{{authority control Historically black schools Historically black universities and colleges in the United States Music schools in Kansas History of Kansas Abolitionism in the United States Defunct universities and colleges in Kansas 1943 disestablishments in Kansas 1865 establishments in Kansas Educational institutions established in 1865 Educational institutions disestablished in 1943