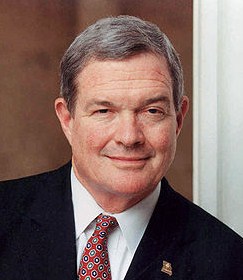

Wendell H. Ford on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Wendell Hampton Ford (September 8, 1924 – January 22, 2015) was an American politician from the

Ford went on to win the governorship in a four-way general election that included another former Democratic governor, A. B. "Happy" Chandler, who ran as an

Ford went on to win the governorship in a four-way general election that included another former Democratic governor, A. B. "Happy" Chandler, who ran as an  Ford united the state's Democratic Party, allowing them to capture a seat in the U.S. Senate in 1972 for the first time since 1956. The seat was vacated by the retirement of Republican

Ford united the state's Democratic Party, allowing them to capture a seat in the U.S. Senate in 1972 for the first time since 1956. The seat was vacated by the retirement of Republican

During the Ninety-eighth Congress (1983–1985), Ford served on the Select Committee to Study the Committee System, and he was a member of the Committee on Rules and Administration in the One Hundredth through One Hundred Third Congresses (1987–1995). In 1989, he joined with Missouri senator

During the Ninety-eighth Congress (1983–1985), Ford served on the Select Committee to Study the Committee System, and he was a member of the Committee on Rules and Administration in the One Hundredth through One Hundred Third Congresses (1987–1995). In 1989, he joined with Missouri senator

Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

of Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

. He served for twenty-four years in the U.S. Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and powe ...

and was the 53rd Governor of Kentucky

The governor of the Commonwealth of Kentucky is the head of government of Kentucky. Sixty-two men and one woman have served as governor of Kentucky. The governor's term is four years in length; since 1992, incumbents have been able to seek re-el ...

. He was the first person to be successively elected lieutenant governor

A lieutenant governor, lieutenant-governor, or vice governor is a high officer of state, whose precise role and rank vary by jurisdiction. Often a lieutenant governor is the deputy, or lieutenant, to or ranked under a governor — a "second-in-comm ...

, governor and United States senator in Kentucky history.Jones, p. 211 The Senate Democratic whip from 1991 to 1999, he was considered the leader of the state's Democratic Party from his election to governor in 1971 until he retired from the Senate in 1999.Cross, 1A At the time of his retirement, he was the longest-serving senator in Kentucky's history, a mark which was then surpassed by Mitch McConnell

Addison Mitchell McConnell III (born February 20, 1942) is an American politician and retired attorney serving as the senior United States senator from Kentucky and the Senate minority leader since 2021. Currently in his seventh term, McConne ...

in 2009. He is the most recent Democrat to have served as a Senator from the state of Kentucky.

Born in Daviess County, Kentucky

Daviess County ( "Davis"), is a county in Kentucky. As of the 2020 census, the population was 103,312. Its county seat is Owensboro. The county was formed from part of Ohio County on January 14, 1815.

Daviess County is included in the Owensbo ...

, Ford attended the University of Kentucky

The University of Kentucky (UK, UKY, or U of K) is a Public University, public Land-grant University, land-grant research university in Lexington, Kentucky. Founded in 1865 by John Bryan Bowman as the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Kentu ...

, but his studies were interrupted by his service in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. After the war, he graduated from the Maryland School of Insurance and returned to Kentucky to help his father with the family insurance business. He also continued his military service in the Kentucky Army National Guard

The Kentucky Army National Guard is a component of the United States Army and the United States National Guard. Nationwide, the Army National Guard comprises approximately one half of the US Army's available combat forces and approximately one t ...

. He worked on the gubernatorial campaign of Bert T. Combs

Bertram Thomas Combs (August 13, 1911 – December 4, 1991) was an American judge, jurist and politician from the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Kentucky. After serving on the Kentucky Court of Appeals, he was elected the List of Gov ...

in 1959 and became Combs' executive assistant when Combs was elected governor. Encouraged to run for the Kentucky Senate

The Kentucky Senate is the upper house of the Kentucky General Assembly. The Kentucky Senate is composed of 38 members elected from single-member districts throughout the Commonwealth. There are no term limits for Kentucky Senators. The Kentu ...

by Combs' ally and successor, Ned Breathitt

Edward Thompson Breathitt Jr. (November 26, 1924October 14, 2003) was an American politician from the Commonwealth of Kentucky. A member of one of the state's political families, he was the 51st Governor of Kentucky, serving from 1963 to 1967. A ...

, Ford won the seat and served one four-year term before running for lieutenant governor in 1967. He was elected on a split ticket

Split-ticket voting is when a voter in an election votes for candidates from different political parties when multiple offices are being decided by a single election, as opposed to straight-ticket voting, where a voter chooses candidates from the ...

with Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

Louie B. Nunn

Louie Broady Nunn (March 8, 1924 – January 29, 2004) was an American politician who served as the 52nd governor of Kentucky. Elected in 1967, he was the only Republican to hold the office between the end of Simeon Willis's term in 1947 and ...

. Four years later, Ford defeated Combs in an upset in the Democratic primary

Primary or primaries may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Music Groups and labels

* Primary (band), from Australia

* Primary (musician), hip hop musician and record producer from South Korea

* Primary Music, Israeli record label

Works

* ...

en route to the governorship.

As governor, Ford made the government more efficient by reorganizing and consolidating some departments in the executive branch. He raised revenue for the state through a severance tax

Severance taxes are taxes imposed on the removal of natural resources within a taxing jurisdiction. Severance taxes are most commonly imposed in oil producing states within the United States. Resources that typically incur severance taxes when e ...

on coal and enacted reforms to the educational system. He purged most of the Republicans from statewide office, including helping Walter "Dee" Huddleston win the Senate seat vacated by the retirement of Republican stalwart John Sherman Cooper

John Sherman Cooper (August 23, 1901 – February 21, 1991) was an American politician, jurist, and diplomat from the Commonwealth of Kentucky. He served three non-consecutive, partial terms in the United States Senate before being elect ...

. In 1974, Ford himself ousted the other incumbent senator, Republican Marlow Cook

Marlow Webster Cook (July 27, 1926 – February 4, 2016) was an American politician who served Kentucky in the United States Senate from his appointment in December 1968 to his resignation in December 1974. He was a moderate Republican.

He ...

. Following the rapid rise of Ford and many of his political allies, he and his lieutenant governor, Julian Carroll

Julian Morton Carroll (born April 16, 1931) is an American lawyer and politician from the state of Kentucky. A Democrat, he served as the 54th Governor of Kentucky from 1974 to 1979, succeeding Wendell H. Ford, who resigned to accept a seat ...

, were investigated on charges of political corruption

Political corruption is the use of powers by government officials or their network contacts for illegitimate private gain.

Forms of corruption vary, but can include bribery, lobbying, extortion, cronyism, nepotism, parochialism, patronage, in ...

, but a grand jury

A grand jury is a jury—a group of citizens—empowered by law to conduct legal proceedings, investigate potential criminal conduct, and determine whether criminal charges should be brought. A grand jury may subpoena physical evidence or a pe ...

refused to indict them. As a senator, Ford was a staunch defender of Kentucky's tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ...

industry. He also formed the Senate National Guard Caucus with Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ...

senator Kit Bond

Christopher Samuel "Kit" Bond (born March 6, 1939) is an American attorney, politician and former United States Senator from Missouri and a member of the Republican Party. First elected to the U.S. Senate in 1986, he defeated Democrat Harriett W ...

. Chosen as Democratic party whip in 1991, Ford considered running for floor leader

In politics, floor leaders, also known as a caucus leader, are leaders of their respective political party in a body of a legislature.

Philippines

In the Philippines each body of the bicameral Congress has a majority floor leader and a minor ...

in 1994 before throwing his support to Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its cap ...

's Christopher Dodd

Christopher John Dodd (born May 27, 1944) is an American lobbyist, lawyer, and Democratic Party politician who served as a United States senator from Connecticut from 1981 to 2011. Dodd is the longest-serving senator in Connecticut's history. ...

. He retired from the Senate in 1999 and returned to Owensboro, where he taught politics to youth at the Owensboro Museum of Science and History.

Early life

Wendell Ford was born nearOwensboro

Owensboro is a home rule-class city in and the county seat of Daviess County, Kentucky, United States. It is the fourth-largest city in the state by population. Owensboro is located on U.S. Route 60 and Interstate 165 about southwest of Lou ...

, in Daviess County, Kentucky

Daviess County ( "Davis"), is a county in Kentucky. As of the 2020 census, the population was 103,312. Its county seat is Owensboro. The county was formed from part of Ohio County on January 14, 1815.

Daviess County is included in the Owensbo ...

, on September 8, 1924."Ford, Wendell Hampton". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress He was the son of Ernest M. and Irene Woolfork (Schenk) Ford.Powell, p. 110 His father was a state senator

A state senator is a member of a state's senate in the bicameral legislature of 49 U.S. states, or a member of the unicameral Nebraska Legislature.

Description

A state senator is a member of an upper house in the bicameral legislatures of 49 U ...

and ally of Kentucky Governor Earle C. Clements

Earle Chester Clements (October 22, 1896 – March 12, 1985) was an American farmer and politician. He represented the Commonwealth of Kentucky in both the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate and was its 47th Governor, serving f ...

. Ford obtained his early education in the public schools of Daviess County and graduated from Daviess County High School.Harrison in ''The Kentucky Encyclopedia'', p. 342 From 1942 to 1943, he attended the University of Kentucky

The University of Kentucky (UK, UKY, or U of K) is a Public University, public Land-grant University, land-grant research university in Lexington, Kentucky. Founded in 1865 by John Bryan Bowman as the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Kentu ...

.

On September 18, 1943, Ford married Jean Neel (1924 - living) of Owensboro at the home of the bride's parents."Anniversary Mr. and Mrs. Ford". ''Owensboro Messenger-Inquirer'' The couple had two children. Daughter Shirley (Ford) Dexter was born in 1950 and son Steven Ford was born in 1954. The family attended First Baptist Church in Owensboro.

In 1944, Ford left the University of Kentucky to join the army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

, enlisting for service in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

on July 22, 1944."Senator Wendell Hampton Ford". National Guard History E-Museum He was trained as an administrative non-commissioned officer

A non-commissioned officer (NCO) is a military officer who has not pursued a commission. Non-commissioned officers usually earn their position of authority by promotion through the enlisted ranks. (Non-officers, which includes most or all enli ...

and promoted to the rank of technical sergeant

Technical sergeant is the name of two current and two former enlisted ranks in the United States Armed Forces, as well as in the U.S. Civil Air Patrol. Outside the United States, it is used only by the Philippine Army, Philippine Air Force and th ...

on November 17, 1945. Over the course of his service, he received the American Campaign Medal

The American Campaign Medal is a military award of the United States Armed Forces which was first created on November 6, 1942, by issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The medal was intended to recognize those military members who had perfo ...

and the World War II Victory Medal

The World War II Victory Medal is a service medal of the United States military which was established by an Act of Congress on 6 July 1945 (Public Law 135, 79th Congress) and promulgated by Section V, War Department Bulletin 12, 1945.

The Wor ...

and earned the Expert Infantryman Badge

The Expert Infantryman Badge, or EIB, is a special skills badge of the United States Army.

The EIB was created with the CIB by executive order in November 1943 during World War II. Currently, it is awarded to U.S. Army personnel who hold infan ...

and Good Conduct Medal. He was honorably discharged on June 18, 1946.

Following the war, Ford returned home to work with his father in the family insurance business, and graduated from the Maryland School of Insurance in 1947. On June 7, 1949, he enlisted in the Kentucky Army National Guard

The Kentucky Army National Guard is a component of the United States Army and the United States National Guard. Nationwide, the Army National Guard comprises approximately one half of the US Army's available combat forces and approximately one t ...

and was assigned to Company I of the 149th Infantry Regimental Combat Team in Owensboro. On August 7, 1949, he was promoted to Second Lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army until ...

of Infantry. In 1949, Ford's company

A company, abbreviated as co., is a Legal personality, legal entity representing an association of people, whether Natural person, natural, Legal person, legal or a mixture of both, with a specific objective. Company members share a common p ...

was converted from infantry to tank

A tank is an armoured fighting vehicle intended as a primary offensive weapon in front-line ground combat. Tank designs are a balance of heavy firepower, strong armour, and good battlefield mobility provided by tracks and a powerful engin ...

s, and Ford served as a Company Commander

A company commander is the commanding officer of a company, a military unit which typically consists of 100 to 250 soldiers, often organized into three or four smaller units called platoons. The exact organization of a company varies by country, ...

in the 240th Tank Battalion. Promoted to First Lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a s ...

of Armor, he transferred to the inactive Guard in 1956, before being discharged in 1962.

Political career

Ford was very active in civic affairs, becoming the first Kentuckian to serve as president of theJaycees

The United States Junior Chamber, also known as the Jaycees, JCs or JCI USA, is a leadership training, service organization and civic organization for people between the ages of 18 and 40. It is a branch of Junior Chamber International (JCI) ...

in 1954. He was a youth chairman of Bert T. Combs

Bertram Thomas Combs (August 13, 1911 – December 4, 1991) was an American judge, jurist and politician from the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Kentucky. After serving on the Kentucky Court of Appeals, he was elected the List of Gov ...

' 1959 gubernatorial campaign. After Combs' election, Ford served as Combs' executive assistant from 1959 to 1963. When his mother died in 1963, Ford returned to Owensboro to help his father with the family insurance agency. Although it was speculated he would run for lieutenant governor that year, Ford later insisted he had decided not to re-enter politics until Governor Ned Breathitt

Edward Thompson Breathitt Jr. (November 26, 1924October 14, 2003) was an American politician from the Commonwealth of Kentucky. A member of one of the state's political families, he was the 51st Governor of Kentucky, serving from 1963 to 1967. A ...

asked him to run against Casper "Cap" Gardner, the state senate's majority leader

In U.S. politics (as well as in some other countries utilizing the presidential system), the majority floor leader is a partisan position in a legislative body.

and a major obstacle to Breathitt's progressive

Progressive may refer to:

Politics

* Progressivism, a political philosophy in support of social reform

** Progressivism in the United States, the political philosophy in the American context

* Progressive realism, an American foreign policy par ...

legislative agenda. Ford won the 1965 election by only 305 votes but quickly became a key player in the state senate. Representing the Eighth District, including Daviess and Hancock Hancock may refer to:

Places in the United States

* Hancock, Iowa

* Hancock, Maine

* Hancock, Maryland

* Hancock, Massachusetts

* Hancock, Michigan

* Hancock, Minnesota

* Hancock, Missouri

* Hancock, New Hampshire

** Hancock (CDP), New Hampshire

* ...

counties, Ford introduced 22 major pieces of legislation that became law during his single term in the senate.

In 1967, Ford ran for lieutenant governor

A lieutenant governor, lieutenant-governor, or vice governor is a high officer of state, whose precise role and rank vary by jurisdiction. Often a lieutenant governor is the deputy, or lieutenant, to or ranked under a governor — a "second-in-comm ...

, this time against the wishes of Breathitt and Combs, whose pick was state attorney general

The state attorney general in each of the 50 U.S. states, of the federal district, or of any of the territories is the chief legal advisor to the state government and the state's chief law enforcement officer. In some states, the attorney genera ...

Robert Matthews. Ford defeated Matthews by 631 votes, 0.2% of the total vote count in the primary

Primary or primaries may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Music Groups and labels

* Primary (band), from Australia

* Primary (musician), hip hop musician and record producer from South Korea

* Primary Music, Israeli record label

Works

* ...

. He ran an independent campaign and won in the general election even as Combs-Breathitt pick Henry Ward lost the race for governor to Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

Louie B. Nunn

Louie Broady Nunn (March 8, 1924 – January 29, 2004) was an American politician who served as the 52nd governor of Kentucky. Elected in 1967, he was the only Republican to hold the office between the end of Simeon Willis's term in 1947 and ...

. Republicans and Democrats split the state offices, with five going to Republicans and four going to Democrats.

During his time as lieutenant governor, Ford rebuilt the state's Democratic machine

A machine is a physical system using Power (physics), power to apply Force, forces and control Motion, movement to perform an action. The term is commonly applied to artificial devices, such as those employing engines or motors, but also to na ...

, which would help elect him and others, including Senator Walter Huddleston

Walter Darlington "Dee" Huddleston (April 15, 1926 – October 16, 2018) was an American politician. He was a Democrat from Kentucky who represented the state in the United States Senate from 1973 until 1985. Huddleston lost his 1984 Senate re- ...

and Governor Martha Layne Collins

Martha Layne Collins (née Hall; born December 7, 1936) is an American former businesswoman and politician from the Commonwealth of Kentucky; she was elected as the state's 56th governor from 1983 to 1987, the first woman to hold the office and ...

. When Governor Nunn asked the legislature to increase the state sales tax

A sales tax is a tax paid to a governing body for the sales of certain goods and services. Usually laws allow the seller to collect funds for the tax from the consumer at the point of purchase. When a tax on goods or services is paid to a govern ...

in 1968 from 3 percent to 5 percent, Ford opposed the measure, saying it should only pass if food and medicine were exempted. Ford lost this battle; the increase passed without exemptions. From 1970 to 1971, Ford was a member of the Executive Committee of the National Conference of Lieutenant Governors."Kentucky Governor Wendell Hampton Ford". National Governors Association While lieutenant governor, he became an honorary member of Lambda Chi Alpha Fraternity in 1969.

Governor of Kentucky

At the expiration of his term as lieutenant governor, Ford was one of eight candidates to enter the 1971 Democratic gubernatorial primary. The favorite of the field was Ford's mentor, Combs. During the campaign, Ford attacked Combs' age and the sales tax enacted during Combs' administration.Harrison in ''A New History of Kentucky'', p. 415 He also questioned why Combs would leave his better-paying federal judgeship to run for a second term as governor. Ford garnered more votes than Combs and the other six candidates combined, and attributed his unlikely win over Combs in the primary to superior strategy and Combs' underestimation of his candidacy. Following the election, Combs correctly predicted "This is the end of the road for me politically." Ford went on to win the governorship in a four-way general election that included another former Democratic governor, A. B. "Happy" Chandler, who ran as an

Ford went on to win the governorship in a four-way general election that included another former Democratic governor, A. B. "Happy" Chandler, who ran as an independent

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in the New Hope, Pennsylvania, area of the United States during the early 1930s

* Independ ...

. Ford finished more than 58,000 votes ahead of his closest rival, Republican Tom Emberton

Thomas Dale Emberton Sr. (July 14, 1932 — October 20, 2022) was an American politician and judge in the state of Kentucky. He was the Republican nominee for his state's governorship in the 1971 election. Of note, Mitch McConnell worked on his ...

. With Combs and Chandler both out of politics, factionalism in the Kentucky Democratic Party began to wane.

As governor, Ford raised revenue from a severance tax

Severance taxes are taxes imposed on the removal of natural resources within a taxing jurisdiction. Severance taxes are most commonly imposed in oil producing states within the United States. Resources that typically incur severance taxes when e ...

on coal, a two-cent-per-gallon tax on gasoline, and an increased corporate tax. He balanced these increases by exempting food from the state sales tax. The resulting large budget surplus allowed him to propose several construction projects. His victory in the primary had been largely due to Jefferson County, and he returned the favor by approving funds to build the Commonwealth Convention Center

The Kentucky International Convention Center (KICC), formerly called the Commonwealth Convention Center, is a large multi-use facility in Louisville, Kentucky, United States. The KICC, along with the Kentucky Exposition Center, hosts conventions f ...

and expand the Kentucky Fair and Exposition Center

The Kentucky Exposition Center (KEC), is a large multi-use facility in Louisville, Kentucky, United States. Originally built in 1956. It is overseen by the Kentucky Venues and is the sixth largest facility of its type in the U.S., with of indoor ...

. He also shepherded a package of reforms to the state's criminal justice system through the first legislative session of his term.

Ford oversaw the transition of the University of Louisville

The University of Louisville (UofL) is a public research university in Louisville, Kentucky. It is part of the Kentucky state university system. When founded in 1798, it was the first city-owned public university in the United States and one of ...

from municipal to state funding. He pushed for reforms to the state's education system, giving up his own chairmanship of the University of Kentucky board of trustees and extending voting rights to student and faculty members of university boards. These changes generally shifted administration positions in the state's colleges from political rewards to professional appointments. He increased funding to the state's education budget and gave expanded powers to the Council on Higher Education. He veto

A veto is a legal power to unilaterally stop an official action. In the most typical case, a president or monarch vetoes a bill to stop it from becoming law. In many countries, veto powers are established in the country's constitution. Veto ...

ed a measure that would have allowed collective bargaining

Collective bargaining is a process of negotiation between employers and a group of employees aimed at agreements to regulate working salaries, working conditions, benefits, and other aspects of workers' compensation and rights for workers. The i ...

for teachers.

Ford drew praise for his attention to the mundane task of improving the efficiency and organization of executive departments, creating several "super cabinets" under which many departments were consolidated.Jones, p. 214 During the 1972 legislative session, he created the Department of Finance and Administration, combining the functions of the Kentucky Program Development Office and the Department of Finance. Constitutional limits sometimes prevented him from combining like functions, but Ford made the reorganization a top priority and realized some savings to the state.

On March 21, 1972, the U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

handed down its ruling in the case of ''Dunn v. Blumstein Dunn may refer to:

Places in the United States

* Dunn, Indiana, a ghost town

* Dunn, Missouri, an unincorporated community

* Dunn, North Carolina, a city

* Dunn County, North Dakota, county

* Dunn, Texas, an unincorporated community

* Dunn County ...

'' that found that a citizen who had lived in a state for 30 days was resident in that state and thus eligible to vote there."Dunn v. Blumstein". The Oyez Project Kentucky's Constitution required residency of one year in the state, six months in the county and sixty days in the precinct to establish voting eligibility.Van Curon, p. 27 This issue had to be resolved before the 1972 presidential election in November, so Ford called a special legislative session to enact the necessary corrections. In addition, Ford added to the General Assembly's agenda the creation of a state environmental protection agency, a refinement of congressional districts in line with the latest census figures and ratification of the recently passed Equal Rights Amendment

The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) is a proposed amendment to the United States Constitution designed to guarantee equal legal rights for all American citizens regardless of sex. Proponents assert it would end legal distinctions between men and ...

. All of these measures passed.Jones, p. 213

Despite surgery for a brain aneurysm

An aneurysm is an outward bulging, likened to a bubble or balloon, caused by a localized, abnormal, weak spot on a blood vessel wall. Aneurysms may be a result of a hereditary condition or an acquired disease. Aneurysms can also be a nidus (s ...

in June 1972, Ford attended the 1972 Democratic National Convention

The 1972 Democratic National Convention was the presidential nominating convention of the Democratic Party for the 1972 presidential election. It was held at Miami Beach Convention Center in Miami Beach, Florida, also the host city of the Rep ...

in Miami Beach, Florida

Miami Beach is a coastal resort city in Miami-Dade County, Florida. It was incorporated on March 26, 1915. The municipality is located on natural and artificial island, man-made barrier islands between the Atlantic Ocean and Biscayne Bay, the ...

. He supported Edmund Muskie

Edmund Sixtus Muskie (March 28, 1914March 26, 1996) was an American statesman and political leader who served as the 58th United States Secretary of State under President Jimmy Carter, a United States Senator from Maine from 1959 to 1980, the 6 ...

for president, but later greeted nominee George McGovern

George Stanley McGovern (July 19, 1922 – October 21, 2012) was an American historian and South Dakota politician who was a U.S. representative and three-term U.S. senator, and the Democratic Party presidential nominee in the 1972 pres ...

when he visited Kentucky. The convention was the beginning of Ford's role in national politics. Offended by the McGovern campaign's treatment of Democratic finance chairman Robert Schwarz Strauss

Robert Schwarz Strauss (October 19, 1918 – March 19, 2014) was an influential figure in American politics, diplomacy, and law whose service dated back to future President Lyndon Johnson's first congressional campaign in 1937. By the 1950s, he ...

, he helped Strauss get elected chairman of the Democratic National Committee

The Democratic National Committee (DNC) is the governing body of the United States Democratic Party. The committee coordinates strategy to support Democratic Party candidates throughout the country for local, state, and national office, as well a ...

following McGovern's defeat. As a result of his involvement in Strauss' election, Ford was elected chair of the Democratic Governors' Conference from 1973 to 1974. He also served as vice-chair of the Conference's Natural Resources and Environmental Management Committee.

During the 1974 legislative session, Ford proposed a six-year study of coal liquefaction

Coal liquefaction is a process of converting coal into liquid hydrocarbons: liquid fuels and petrochemicals. This process is often known as "Coal to X" or "Carbon to X", where X can be many different hydrocarbon-based products. However, the most c ...

and gasification

Gasification is a process that converts biomass- or fossil fuel-based carbonaceous materials into gases, including as the largest fractions: nitrogen (N2), carbon monoxide (CO), hydrogen (H2), and carbon dioxide (). This is achieved by reacting ...

in response to the 1973 oil crisis

The 1973 oil crisis or first oil crisis began in October 1973 when the members of the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC), led by Saudi Arabia, proclaimed an oil embargo. The embargo was targeted at nations that had supp ...

. He also increased funding to human resources and continued his reorganization of the executive branch, creating cabinets for transportation, development, education and the arts, human resources, consumer protection and regulation, safety and justice. He was considered less ruthless than previous governors in firing state officials hired by the previous administration, and expanded the state merit system The merit system is the process of promoting and hiring government employees based on their ability to perform a job, rather than on their political connections. It is the opposite of the spoils system.

History

The earliest known example of a me ...

to cover some previously exempt state workers. Despite the expansion, he was criticized for the replacements he made, particularly that of the state personnel commissioner appointed during the Nunn administration. Critics also cited the fact that employees found qualified by the merit examination were still required to obtain political clearance before they were hired.

Ford united the state's Democratic Party, allowing them to capture a seat in the U.S. Senate in 1972 for the first time since 1956. The seat was vacated by the retirement of Republican

Ford united the state's Democratic Party, allowing them to capture a seat in the U.S. Senate in 1972 for the first time since 1956. The seat was vacated by the retirement of Republican John Sherman Cooper

John Sherman Cooper (August 23, 1901 – February 21, 1991) was an American politician, jurist, and diplomat from the Commonwealth of Kentucky. He served three non-consecutive, partial terms in the United States Senate before being elect ...

and won by Ford's campaign manager, Walter Dee Huddleston

Walter Darlington "Dee" Huddleston (April 15, 1926 – October 16, 2018) was an American politician. He was a Democrat from Kentucky who represented the state in the United States Senate from 1973 until 1985. Huddleston lost his 1984 Senate re ...

. Ford's friends then began lobbying him to try and unseat Kentucky's other Republican senator, one-term legislator Marlow Cook

Marlow Webster Cook (July 27, 1926 – February 4, 2016) was an American politician who served Kentucky in the United States Senate from his appointment in December 1968 to his resignation in December 1974. He was a moderate Republican.

He ...

. Ford wanted lieutenant governor Julian Carroll

Julian Morton Carroll (born April 16, 1931) is an American lawyer and politician from the state of Kentucky. A Democrat, he served as the 54th Governor of Kentucky from 1974 to 1979, succeeding Wendell H. Ford, who resigned to accept a seat ...

, who had run on an informal slate with Combs in the 1971 primary, to run for Cook's seat, but Carroll already had his eye on the governor's chair. Ford's allies did not have a gubernatorial candidate stronger than Carroll, and when a poll showed that Ford was the only Democrat who could defeat Cook, he agreed to run, announcing his candidacy immediately following the 1974 legislative session.

A primary issue during the election was the construction of a dam on the Red River.Jones, p. 215 Cook opposed the dam, but Ford supported it and allocated some of the state's budget surplus to its construction. In the election

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has opera ...

, Ford defeated Cook by a vote of 399,406 to 328,982, completing his revitalization of the state's Democratic party by personally ousting the last Republican from major office. Cook resigned his seat in December so that Ford would have a higher standing in seniority in the Senate. Ford resigned as governor to accept the seat, leaving the governorship to Carroll, who dropped state support for the project, killing it.

In the wake of the rapid ascent of Ford and members of his faction to the state's major political offices, he and Carroll were investigated in a corruption probe. The four-year investigation began in 1977 and focused on a state insurance kickback scheme alleged to have operated during Ford's tenure. In June 1972, Ford had purchased insurance policies for state workers from some of his political backers without competitive bidding

Procurement is the method of discovering and agreeing to terms and purchasing goods, services, or other works from an external source, often with the use of a tendering or competitive bidding process. When a government agency buys goods or serv ...

. State law did not require competitive bidding, and earlier governors had engaged in similar practices. Investigators believed there was an arrangement in which insurance companies getting government contracts split commissions with party officials, although Ford was suspected of allowing the practice for political benefit rather than personal financial gain.Babcock, A4 In 1981, prosecutors asked for indictments against Ford and Carroll on racketeering

Racketeering is a type of organized crime in which the perpetrators set up a coercive, fraudulent, extortionary, or otherwise illegal coordinated scheme or operation (a "racket") to repeatedly or consistently collect a profit.

Originally and of ...

charges but a grand jury

A grand jury is a jury—a group of citizens—empowered by law to conduct legal proceedings, investigate potential criminal conduct, and determine whether criminal charges should be brought. A grand jury may subpoena physical evidence or a pe ...

refused. Because grand jury proceedings are secret, what exactly occurred has never been publicly revealed. However, state Republicans maintained that Ford took the Fifth Amendment while on the stand, invoking his right against self-incrimination. Ford refused to confirm or deny this report. A federal grand jury recommended that Ford be indicted in connection with the insurance scheme, but the U.S. Department of Justice did not act on this recommendation.

United States Senate

Ford entered the Senate in 1974 and was reelected in 1980, 1986 and 1992. In the 1980 primary, Ford received only token opposition from attorney Flora Stuart.Ramsey, p. 5 He was unopposed in the 1986 and 1992 Democratic primaries. Republicans failed to put forward a viable challenger during any of Ford's re-election bids. In 1980, he defeated septuagenarian former state auditorMary Louise Foust

Mary Louise Foust (October 15, 1909 – December 17, 1999) served three terms as the State auditor, Kentucky Auditor of Public Accounts and was the first woman to run for Governor of Kentucky. She was also the first woman in the state to be a ...

by 334,862 votes.Miller, p. A1 Ford's 720,891 votes represented 65 percent of the total votes cast in the election, a record for a statewide race in Kentucky. Against Republican Jackson Andrews IV in 1986, Ford shattered that record, securing 74 percent of the votes cast and carrying all 120 Kentucky counties. State senator David L. Williams fared little better in 1992

File:1992 Events Collage V1.png, From left, clockwise: 1992 Los Angeles riots, Riots break out across Los Angeles, California after the Police brutality, police beating of Rodney King; El Al Flight 1862 crashes into a residential apartment buildi ...

, surrendering 477,002 votes to Ford (63 percent).Gibson, p. 9K

Ford seriously considered leaving the Senate and running for governor again in 1983 and 1991, but decided against it both times. In the 1983 contest, he would have faced sitting lieutenant governor Martha Layne Collins

Martha Layne Collins (née Hall; born December 7, 1936) is an American former businesswoman and politician from the Commonwealth of Kentucky; she was elected as the state's 56th governor from 1983 to 1987, the first woman to hold the office and ...

in the primary. Collins was a factional ally of Ford's, which influenced his decision. In 1991, Ford cited his seniority in the Senate and desire to become Democratic Senate whip as factors in his decision not to run for governor.Heckel, p. 1A

Early in his career, Ford supported a constitutional amendment

A constitutional amendment is a modification of the constitution of a polity, organization or other type of entity. Amendments are often interwoven into the relevant sections of an existing constitution, directly altering the text. Conversely, t ...

against desegregation busing

Race-integration busing in the United States (also known simply as busing, Integrated busing or by its critics as forced busing) was the practice of assigning and student transport, transporting students to schools within or outside their local s ...

. He also floated a proposal to put the federal budget on a two-year cycle, believing too much time was spent annually on budget wrangling. This idea, based on the model used in the Kentucky state budget, was never implemented. During the Ninety-fifth Congress (1977–1979), he was chairman of the Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences.

From 1977 to 1983, Ford was a member of the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee

The Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee (DSCC) is the United States Democratic Party, Democratic Hill committee for the United States Senate. It is the only organization solely dedicated to electing Democrats to the United States Senate. ...

. He first sought the post of Democratic whip in 1988, but lost to California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

's Alan Cranston

Alan MacGregor Cranston (June 19, 1914 – December 31, 2000) was an American politician and journalist who served as a United States Senator from California from 1969 to 1993, and as a President of the World Federalist Association from 1949 to 1 ...

, who had held the post since 1977.Nash, p. A20 Ford got a late start in the race, and a ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'' writer opined that he overestimated his chances of unseating Cranston. Immediately after conceding his loss, he announced he would be a candidate for the position in the next election in 1990. He again faced Cranston in the election, but Cranston withdrew from the race due to a battle with prostate cancer

Prostate cancer is cancer of the prostate. Prostate cancer is the second most common cancerous tumor worldwide and is the fifth leading cause of cancer-related mortality among men. The prostate is a gland in the male reproductive system that sur ...

. Ford maintained that he had enough commitments of support in the Democratic caucus to have won without Cranston's withdrawal. When majority leader George J. Mitchell

George John Mitchell Jr. (born August 20, 1933) is an American politician, diplomat, and lawyer. A leading member of the Democratic Party, he served as a United States senator from Maine from 1980 to 1995, and as Senate Majority Leader from 198 ...

retired from the Senate in 1994, Ford showed some interest in the Democratic floor leader post. Ultimately, he decided against it, choosing to focus instead on Kentucky issues. He supported Christopher Dodd

Christopher John Dodd (born May 27, 1944) is an American lobbyist, lawyer, and Democratic Party politician who served as a United States senator from Connecticut from 1981 to 2011. Dodd is the longest-serving senator in Connecticut's history. ...

for majority leader.

During the Ninety-eighth Congress (1983–1985), Ford served on the Select Committee to Study the Committee System, and he was a member of the Committee on Rules and Administration in the One Hundredth through One Hundred Third Congresses (1987–1995). In 1989, he joined with Missouri senator

During the Ninety-eighth Congress (1983–1985), Ford served on the Select Committee to Study the Committee System, and he was a member of the Committee on Rules and Administration in the One Hundredth through One Hundred Third Congresses (1987–1995). In 1989, he joined with Missouri senator Kit Bond

Christopher Samuel "Kit" Bond (born March 6, 1939) is an American attorney, politician and former United States Senator from Missouri and a member of the Republican Party. First elected to the U.S. Senate in 1986, he defeated Democrat Harriett W ...

to form the Senate National Guard Caucus, a coalition of senators committed to advancing National Guard capabilities and readiness."Four-term Senator, lifetime citizen soldier". ''National Guard'' Ford said he was motivated to form the caucus after seeing the work done by Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

Representative

Representative may refer to:

Politics

*Representative democracy, type of democracy in which elected officials represent a group of people

*House of Representatives, legislative body in various countries or sub-national entities

*Legislator, someon ...

Sonny Montgomery

Gillespie V. "Sonny" Montgomery (August 5, 1920 – May 12, 2006) was an American soldier and politician from Mississippi who served in the Mississippi Senate and U.S. House of Representatives from 1967 to 1997. He was also a retired major genera ...

with the National Guard Association and the National Guard Bureau

The National Guard Bureau is the federal instrument responsible for the administration of the National Guard established by the United States Congress as a joint bureau of the Department of the Army and the Department of the Air Force. It was cre ...

. Ford co-chaired the caucus with Bond until Ford's retirement from the Senate in 1999. The Kentucky Army Guard dedicated the Wendell H. Ford Training Center in Muhlenberg County, Kentucky

Muhlenberg County () is a county in the U.S. Commonwealth of Kentucky. As of the 2020 census, the population was 30,928. Its county seat is Greenville.

History

Muhlenberg County was formed in 1798 from the areas known as Logan and Christian ...

in 1998."Kentucky Army Guard Dedicates New Training Site to Senator Ford". ''National Guard'' In 1999, the National Guard Bureau presented Ford with the Sonny Montgomery Award, its highest honor.Haskell, p. 10

Missouri senator Thomas Eagleton

Thomas Francis Eagleton (September 4, 1929 – March 4, 2007) was an American lawyer serving as a United States senator from Missouri, from 1968 to 1987. He was briefly the Democratic vice presidential nominee under George McGovern in 1972. He ...

opined that Ford and Dee Huddleston made "probably the best one-two combination for any state in the Senate."King, p. 8 Both were defenders of tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ...

, Kentucky's primary cash crop

A cash crop or profit crop is an Agriculture, agricultural crop which is grown to sell for profit. It is typically purchased by parties separate from a farm. The term is used to differentiate marketed crops from staple crop (or "subsistence crop") ...

. Ford sat on the Commerce Committee, influencing legislation affecting the manufacturing end of the tobacco industry, while Huddleston sat on the Agriculture Committee and protected programs that benefited tobacco farmers. Both were instrumental in salvaging the Tobacco Price Support Program. Ford got tobacco exempted from the Consumer Product Safety Act

The Consumer Safety Act (CPSA) was enacted on October 27th, 1972 by the United States Congress. The act should not be confused with an earlier Senate Joint Resolution 33 of November 20, 1967, which merely established a temporary National Commissio ...

and was a consistent opponent of cigarette tax

A cigarette is a narrow cylinder containing a combustible material, typically tobacco, that is rolled into thin paper for smoking. The cigarette is ignited at one end, causing it to smolder; the resulting smoke is orally inhaled via the oppo ...

increases. He sponsored an amendment to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade

The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) is a legal agreement between many countries, whose overall purpose was to promote international trade by reducing or eliminating trade barriers such as tariffs or quotas. According to its pre ...

that limited the amount of foreign tobacco that could be imported by the United States.

Later in his career, Ford split with Huddleston's successor, Mitch McConnell

Addison Mitchell McConnell III (born February 20, 1942) is an American politician and retired attorney serving as the senior United States senator from Kentucky and the Senate minority leader since 2021. Currently in his seventh term, McConne ...

, over a proposed settlement of lawsuits against tobacco companies. Ford favored the package as presented to Congress, which would have protected the price support program, while McConnell favored a smaller aid package to tobacco farmers and an end to the price support program. Both proposals were ultimately defeated, and the rift between Ford and McConnell never healed.

As chairman of the Commerce Committee's aviation subcommittee, Ford secured funds to improve the airports in Louisville

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border.

...

, northern Kentucky

Northern Kentucky is the third-largest metropolitan area in the U.S. Commonwealth of Kentucky after Louisville and Lexington, and its cities and towns serve as the de facto "south side" communities of Cincinnati, Ohio. The three main counties ...

, and Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

. The Wendell H. Ford Airport in Hazard, Kentucky

Hazard is a list of Kentucky cities, home rule-class city in, and the county seat of, Perry County, Kentucky, Perry County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 5,263 at the 2020 Census.

History

Local landowner Elijah Combs, Elijah Comb ...

is named for him. A 1990 bill aimed at reducing aircraft noise

Aircraft noise pollution refers to noise produced by aircraft in flight that has been associated with several negative stress-mediated health effects, from sleep disorders to cardiovascular ones. Governments have enacted extensive controls that a ...

, improving airline safety measures, and requiring airlines to better inform consumers about their performance was dubbed the Wendell H. Ford Aviation Investment and Reform Act for the 21st Century

The Wendell H. Ford Aviation Investment and Reform Act for the 21st Century is a United States federal law, signed on 5 April 2000, seeking to improve airline safety. It is popularly called "AIR 21," and is also known as Public Law 106-181.

Bac ...

.

Of his career in the Senate, Ford said "I wasn't interested in national issues. I was interested in Kentucky issues." Nevertheless, he influenced several important pieces of federal legislation. He sponsored an amendment to the Family Medical Leave Act

The Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 (FMLA) is a United States labor law requiring covered employers to provide employees with job-protected, unpaid leave for qualified medical and family reasons. The FMLA was a major part of President Bill C ...

exempting businesses with fewer than fifty employees. He was a key player in securing passage of the motor voter law in 1993. He supported increases to the federal minimum wage

A minimum wage is the lowest remuneration that employers can legally pay their employees—the price floor below which employees may not sell their labor. Most countries had introduced minimum wage legislation by the end of the 20th century. Bec ...

and a 1996 welfare reform bill. A supporter of research into clean coal technology

Coal pollution mitigation, sometimes called clean coal, is a series of systems and technologies that seek to mitigate the health and environmental impact of coal; in particular air pollution from coal-fired power stations, and from coal burnt b ...

, he also worked with West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the Bur ...

senator Jay Rockefeller

John Davison "Jay" Rockefeller IV (born June 18, 1937) is a retired American politician who served as a United States senator from West Virginia (1985–2015). He was first elected to the Senate in 1984, while in office as governor of West Virg ...

to secure better retirement benefits for coal miners. Never known as a major player on international issues, Ford favored continued economic sanctions

Economic sanctions are commercial and financial penalties applied by one or more countries against a targeted self-governing state, group, or individual. Economic sanctions are not necessarily imposed because of economic circumstances—they may ...

against Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

as an alternative to the Gulf War

The Gulf War was a 1990–1991 armed campaign waged by a 35-country military coalition in response to the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. Spearheaded by the United States, the coalition's efforts against Iraq were carried out in two key phases: ...

. He voted against the Panama Canal Treaty

Panama ( , ; es, link=no, Panamá ), officially the Republic of Panama ( es, República de Panamá), is a transcontinental country spanning the southern part of North America and the northern part of South America. It is bordered by Cost ...

, which he perceived to be unpopular with Kentucky voters. Despite having chaired Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton ( né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and agai ...

's inaugural committee in 1993, Ford broke with the administration by voting against the North American Free Trade Agreement

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA ; es, Tratado de Libre Comercio de América del Norte, TLCAN; french: Accord de libre-échange nord-américain, ALÉNA) was an agreement signed by Canada, Mexico, and the United States that crea ...

.Jones, p. 216

As he had as governor of Kentucky, Ford gave attention to improving the efficiency of government. While serving on the Joint Committee on Printing

The Joint Committee on Printing is a Joint committee (legislative), joint committee of the United States Congress devoted to overseeing the functions of the United States Government Publishing Office, Government Publishing Office and general printi ...

during the One Hundred First and One Hundred Third Congresses, he saved the government millions of dollars in printing costs by printing in volume and using recycled paper

The recycling of paper is the process by which waste paper is turned into new paper products. It has a number of important benefits: It saves waste paper from occupying homes of people and producing methane as it breaks down. Because paper fi ...

.Martin, p. 16S In 1998, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

senator John Warner

John William Warner III (February 18, 1927 – May 25, 2021) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the United States Secretary of the Navy from 1972 to 1974 and as a five-term Republican U.S. Senator from Virginia from 1979 to 200 ...

sponsored the Wendell H. Ford Government Publications Reform Act of 1998; Ford signed on as a co-sponsor.Relyea, "Public printing reform and the 105th Congress" The bill would have eliminated the Joint Committee on Printing

The Joint Committee on Printing is a Joint committee (legislative), joint committee of the United States Congress devoted to overseeing the functions of the United States Government Publishing Office, Government Publishing Office and general printi ...

, distributing its authority and functions among the Senate Rules Committee, the House Oversight Committee

The Committee on Oversight and Reform is the main investigative committee of the United States House of Representatives.

The committee's broad jurisdiction and legislative authority make it one of the most influential and powerful panels in the ...

, and the administrator of the Government Printing Office

The United States Government Publishing Office (USGPO or GPO; formerly the United States Government Printing Office) is an agency of the legislative branch of the United States Federal government. The office produces and distributes information ...

. It would also have centralized government printing services and penalized government agencies who did not make their documents available to the printing office to be printed. Opponents of the bill cited the broad powers granted to the printing office and concerns about the erosion of copyright

A copyright is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the exclusive right to copy, distribute, adapt, display, and perform a creative work, usually for a limited time. The creative work may be in a literary, artistic, education ...

protection. The bill was reported favorably out of committee, but was squeezed from the legislative calendar by issues related to the impending impeachment of Bill Clinton

Bill Clinton, the List of Presidents of the United States, 42nd president of the United States, was Federal impeachment in the United States, impeached by the United States House of Representatives of the 105th United States Congress on Decem ...

. Warner did not return to his chairmanship of the Joint Committee on Printing in the next congress, Ford retired from the Senate, and the bill was not re-introduced.

Later life

Ford chose not to seek a fifth term in 1998, and retired to Owensboro. In 1998 he was named an Honorary Member of theAmerican Library Association

The American Library Association (ALA) is a nonprofit organization based in the United States that promotes libraries and library education internationally. It is the oldest and largest library association in the world, with 49,727 members a ...

. He worked for a time as a consultant to Washington lobbying and law firm Dickstein Shapiro Morin & Oshinsky.Cross, p. 1B At the time of his retirement, Ford was the longest-serving senator in Kentucky history."Milestone: McConnell's long tenure marked with distinction" In January 2009, Mitch McConnell

Addison Mitchell McConnell III (born February 20, 1942) is an American politician and retired attorney serving as the senior United States senator from Kentucky and the Senate minority leader since 2021. Currently in his seventh term, McConne ...

surpassed Ford's mark of 24 years in the Senate.

In August 1978, the US 60

U.S. Route 60 is a major east–west United States highway, traveling from southwestern Arizona to the Atlantic Ocean coast in Virginia.

The highway's eastern terminus is in Virginia Beach, Virginia, where it is known as Pacific Avenue, in the ...

bypass around Owensboro was renamed the Wendell H. Ford Expressway.Lawrence, "Bypass at 40" The Western Kentucky Parkway was also renamed the Wendell H. Ford Western Kentucky Parkway during the administration of Governor Paul E. Patton

Paul Edward Patton (born May 26, 1937) is an American politician who served as the 59th governor of Kentucky from 1995 to 2003. Because of a 1992 amendment to the Kentucky Constitution, he was the first governor eligible to run for a second ter ...

.Kocher, p. A1 In 2009, Ford was inducted into the Kentucky Transportation Hall of Fame.Covington, "Ford inducted into Transportation Hall of Fame"

Later in life, Ford taught politics to the youth of Owensboro from the Owensboro Museum of Science and History, which houses a replica of his Senate office. On July 19, 2014, the ''Messenger-Inquirer

''The Messenger-Inquirer'' is a local newspaper in Owensboro, Kentucky. ''The Messenger-Inquirer'' serves 15,087 daily and 20,383 Sunday readers in five counties in western Kentucky.

History

The newspaper's roots trace back to 1875, when Lee Lum ...

'' reported that Ford had been diagnosed with lung cancer

Lung cancer, also known as lung carcinoma (since about 98–99% of all lung cancers are carcinomas), is a malignant lung tumor characterized by uncontrolled cell growth in tissue (biology), tissues of the lung. Lung carcinomas derive from tran ...

.

Ford died at his home on January 22, 2015, at the age of 90 from lung cancer

Lung cancer, also known as lung carcinoma (since about 98–99% of all lung cancers are carcinomas), is a malignant lung tumor characterized by uncontrolled cell growth in tissue (biology), tissues of the lung. Lung carcinomas derive from tran ...

, and was buried at Rosehill Elmwood Cemetery

Rosehill Elmwood Cemetery is located at 1300 Old Hartford Road Owensboro Daviess County Kentucky. There are about 55,000 interments. It is officially recognized as a historical landmark by the state of Kentucky. Notable people buried in the ceme ...

.

See also

*Conservative Democrat

In American politics, a conservative Democrat is a member of the Democratic Party with conservative political views, or with views that are conservative compared to the positions taken by other members of the Democratic Party. Traditionally, co ...

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* * , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Ford, Wendell H. 1924 births 2015 deaths United States Army personnel of World War II Baptists from Kentucky Deaths from lung cancer in Kentucky Democratic Party governors of Kentucky Democratic Party United States senators from Kentucky Democratic Party Kentucky state senators Lieutenant Governors of Kentucky Politicians from Owensboro, Kentucky United States Army officers 20th-century Baptists Kentucky National Guard personnel National Guard (United States) officers 20th-century American politicians