Wang Jingwei on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

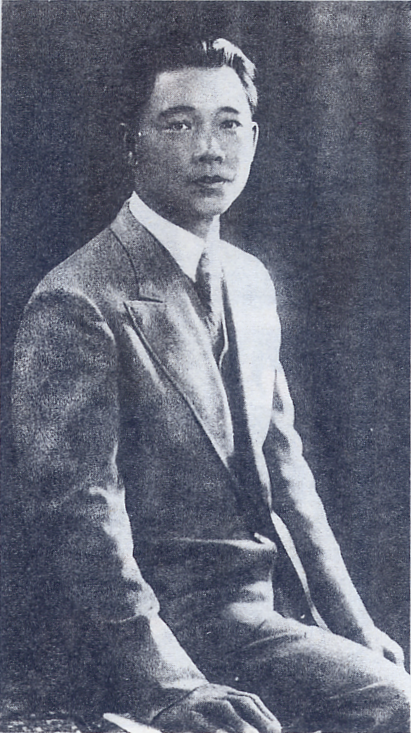

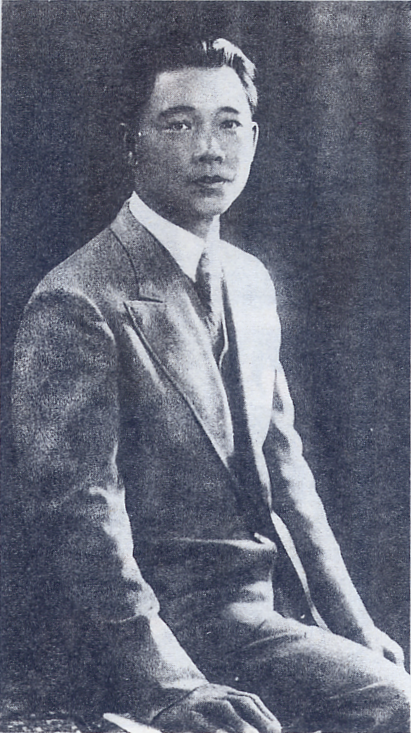

Wang Jingwei (4 May 1883 – 10 November 1944), born as Wang Zhaoming and widely known by his pen name Jingwei, was a Chinese politician. He was initially a member of the

Born in

Born in

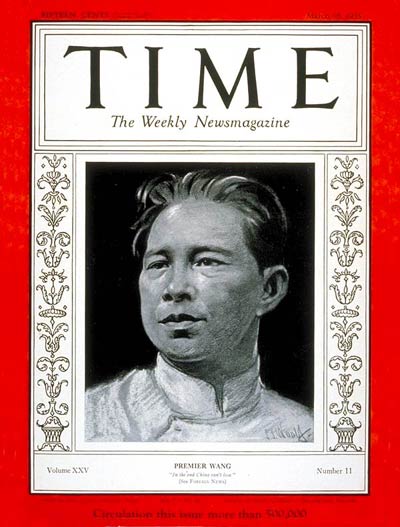

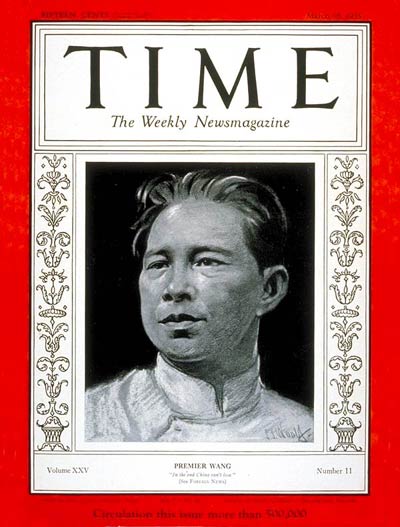

In 1931, Wang joined another anti-Chiang government in Guangzhou. After Chiang defeated this regime, Wang reconciled with Chiang's Nanjing government and held prominent posts for most of the decade. Wang was appointed

In 1931, Wang joined another anti-Chiang government in Guangzhou. After Chiang defeated this regime, Wang reconciled with Chiang's Nanjing government and held prominent posts for most of the decade. Wang was appointed  While being opposed to any effort at this time to subordinate China to Japan, Wang also saw the "white powers" like the Soviet Union, Britain and the United States as equal if not greater dangers to China, insisting that China had to defeat Japan solely by its own efforts if the Chinese were to hope to maintain their independence. But at the same time, Wang's belief that China was too economically backward at present to win a war against a Japan which had been aggressively modernizing since the Meiji Restoration of 1867 made him the advocate of avoiding war with Japan at almost any cost and trying to negotiate some sort of an agreement with Japan which would preserve China's independence. Chiang by contrast believed that if his modernization program was given enough time, China would win the coming war and that if the war came before his modernization plans were complete, he was willing to ally with any foreign power to defeat Japan, even including the Soviet Union, which was supporting the Chinese Communists in the civil war. Chiang was much more of a hardline anti-Communist than was Wang, but Chiang was also a self-proclaimed "realist" who was willing if necessary to have an alliance with the Soviet Union. Though in the short-run, Wang and Chiang agreed on the policy of "first internal pacification, then external resistance", in the long-run they differed as Wang was more of an appeaser while Chiang just wanted to buy time to modernize China for the coming war. The effectiveness of the KMT was constantly hindered by leadership and personal struggles, such as that between Wang and Chiang. In December 1935, Wang permanently left the premiership after being seriously wounded during an assassination attempt engineered a month earlier by

While being opposed to any effort at this time to subordinate China to Japan, Wang also saw the "white powers" like the Soviet Union, Britain and the United States as equal if not greater dangers to China, insisting that China had to defeat Japan solely by its own efforts if the Chinese were to hope to maintain their independence. But at the same time, Wang's belief that China was too economically backward at present to win a war against a Japan which had been aggressively modernizing since the Meiji Restoration of 1867 made him the advocate of avoiding war with Japan at almost any cost and trying to negotiate some sort of an agreement with Japan which would preserve China's independence. Chiang by contrast believed that if his modernization program was given enough time, China would win the coming war and that if the war came before his modernization plans were complete, he was willing to ally with any foreign power to defeat Japan, even including the Soviet Union, which was supporting the Chinese Communists in the civil war. Chiang was much more of a hardline anti-Communist than was Wang, but Chiang was also a self-proclaimed "realist" who was willing if necessary to have an alliance with the Soviet Union. Though in the short-run, Wang and Chiang agreed on the policy of "first internal pacification, then external resistance", in the long-run they differed as Wang was more of an appeaser while Chiang just wanted to buy time to modernize China for the coming war. The effectiveness of the KMT was constantly hindered by leadership and personal struggles, such as that between Wang and Chiang. In December 1935, Wang permanently left the premiership after being seriously wounded during an assassination attempt engineered a month earlier by

In late 1938, Wang left Chongqing for Hanoi, French Indochina, where he stayed for three months and announced his support for a negotiated settlement with the Japanese. During this time, he was wounded in an assassination attempt by KMT agents. Wang then flew to Shanghai, where he entered negotiations with Japanese authorities. The Japanese invasion had given him the opportunity he had long sought to establish a new government outside of Chiang Kai-shek's control.

On 30 March 1940, Wang became the head of state of what came to be known as the

In late 1938, Wang left Chongqing for Hanoi, French Indochina, where he stayed for three months and announced his support for a negotiated settlement with the Japanese. During this time, he was wounded in an assassination attempt by KMT agents. Wang then flew to Shanghai, where he entered negotiations with Japanese authorities. The Japanese invasion had given him the opportunity he had long sought to establish a new government outside of Chiang Kai-shek's control.

On 30 March 1940, Wang became the head of state of what came to be known as the

Chinese National Government of Nanking

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Wang, Jingwei 1883 births 1944 deaths People from Sanshui District Chinese collaborators with Imperial Japan Kuomintang collaborators with Imperial Japan Chinese fascists Chinese people of World War II Chinese revolutionaries Failed assassins Foreign Ministers of the Republic of China Expelled members of the Kuomintang Traitors in history People of the Chinese Civil War Premiers of the Republic of China Presidents of the Republic of China World War II political leaders Republic of China politicians from Guangdong Chinese anti-communists Chinese nationalists Tongmenghui members Chinese expatriates in France People of the Northern Expedition Fascist rulers Politicians from Foshan

left wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

of the Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Tai ...

, leading a government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is a ...

in Wuhan

Wuhan (, ; ; ) is the capital of Hubei, Hubei Province in the China, People's Republic of China. It is the largest city in Hubei and the most populous city in Central China, with a population of over eleven million, the List of cities in China ...

in opposition to the right-wing

Right-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that view certain social orders and hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this position on the basis of natural law, economics, authorit ...

government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is a ...

in Nanjing

Nanjing (; , Mandarin pronunciation: ), alternately romanized as Nanking, is the capital of Jiangsu province of the People's Republic of China. It is a sub-provincial city, a megacity, and the second largest city in the East China region. T ...

, but later became increasingly anti-communist

Anti-communism is Political movement, political and Ideology, ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, w ...

after his efforts to collaborate with the Chinese Communist Party

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), officially the Communist Party of China (CPC), is the founding and One-party state, sole ruling party of the China, People's Republic of China (PRC). Under the leadership of Mao Zedong, the CCP emerged victoriou ...

ended in political failure. His political orientation veered sharply to the right later in his career after he collaborated with the Japanese.

Wang was a close associate of Sun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-sen (; also known by several other names; 12 November 1866 – 12 March 1925)Singtao daily. Saturday edition. 23 October 2010. section A18. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition . was a Chinese politician who serve ...

for the last twenty years of Sun's life. After Sun's death in 1925 Wang engaged in a political struggle with Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

for control over the Kuomintang, but lost. Wang remained inside the Kuomintang, but continued to have disagreements with Chiang until the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific Th ...

in 1937, after which he accepted an invitation from the Japanese Empire

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent forma ...

to form a Japanese-supported collaborationist government in Nanking

Nanjing (; , Mandarin pronunciation: ), alternately romanized as Nanking, is the capital of Jiangsu province of the People's Republic of China. It is a sub-provincial city, a megacity, and the second largest city in the East China region. T ...

. Wang served as the head of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and l ...

for this Japanese puppet government until he died, shortly before the end

End, END, Ending, or variation, may refer to:

End

*In mathematics:

** End (category theory)

** End (topology)

**End (graph theory)

** End (group theory) (a subcase of the previous)

**End (endomorphism)

*In sports and games

**End (gridiron footbal ...

of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. His legacy remains highly controversial among historians. Although he is still regarded as an important contributor in the Xinhai Revolution

The 1911 Revolution, also known as the Xinhai Revolution or Hsinhai Revolution, ended China's last imperial dynasty, the Manchu-led Qing dynasty, and led to the establishment of the Republic of China. The revolution was the culmination of a d ...

, his collaboration with Imperial Japan is a subject of academic debate, and the typical narratives often regard him as a traitor in the War of Resistance with his name becoming synonymous with treason.

Early life and education

Sanshui

Sanshui District, formerly romanized as Samshui, is an urban district of the prefecture-level city of Foshan in Guangdong province, China. It had a population of 622,645 as of the 2010 census. It is known for the " Samsui women", emigrants who la ...

, Guangdong, but of Zhejiang

Zhejiang ( or , ; , also romanized as Chekiang) is an eastern, coastal province of the People's Republic of China. Its capital and largest city is Hangzhou, and other notable cities include Ningbo and Wenzhou. Zhejiang is bordered by Jiang ...

origin, Wang went to Japan as an international student sponsored by the Qing Dynasty government in 1903, and joined the Tongmenghui

The Tongmenghui of China (or T'ung-meng Hui, variously translated as Chinese United League, United League, Chinese Revolutionary Alliance, Chinese Alliance, United Allegiance Society, ) was a secret society and underground resistance movement ...

in 1905. As a young man, Wang came to blame the Qing dynasty for holding China back, and making it too weak to fight off exploitation by Western imperialist powers. While in Japan, Wang became a close confidant of Sun Yat-sen, and would later go on to become one of the most important members of the early Kuomintang. He was among the Chinese nationalists in Japan who were influenced by Russian anarchism

Anarchism in Russia has its roots in the early mutual aid (organization theory), mutual aid systems of the Novgorod Republic, medieval republics and later in the List of peasant revolts, popular resistance to the Tsarist autocracy and Serfdom in R ...

, and published a number of articles in journals edited by Zhang Renjie

Zhang Renjie (Chang Jen-chieh 19 September 1877 − 3 September 1950), born Zhang Jingjiang, was a political figure and financial entrepreneur in the Republic of China. He studied and worked in France in the early 1900s, where he became an early ...

, Wu Zhihui

Wu Jingheng (), commonly known by his courtesy name Wu Zhihui (Woo Chih-hui, ; 1865–1953), also known as Wu Shi-Fee, was a Chinese linguist and philosopher who was the chairman of the 1912–13 Commission on the Unification of Pronunciatio ...

, and the group of Chinese anarchists

Anarchism in China was a strong intellectual force in the reform and revolutionary movements in the early 20th century. In the years before and just after the overthrow of the Qing dynasty Chinese anarchists insisted that a true revolution could ...

in Paris.

Early career

In the years leading up to the Xinhai Revolution in 1911, Wang was active in opposing the Qing government. Wang gained prominence during this period as an excellent public speaker and a staunch advocate ofChinese nationalism

Chinese nationalism () is a form of nationalism in the People's Republic of China (Mainland China) and the Republic of China on Taiwan which asserts that the Chinese people are a nation and promotes the cultural and national unity of all Chi ...

. He was jailed for plotting an assassination of the regent, Prince Chun, and readily admitted his guilt at trial. He remained in jail from 1910 until the Wuchang Uprising

The Wuchang Uprising was an armed rebellion against the ruling Qing dynasty that took place in Wuchang (now Wuchang District of Wuhan), Hubei, China on 10 October 1911, beginning the Xinhai Revolution that successfully overthrew China's last i ...

the next year, and became something of a national hero upon his release.

During and after the Xinhai Revolution, Wang's political life was defined by his opposition to Western imperialism. In the early 1920s, he held several posts in Sun Yat-sen's Revolutionary Government in Guangzhou

Guangzhou (, ; ; or ; ), also known as Canton () and alternatively romanized as Kwongchow or Kwangchow, is the capital and largest city of Guangdong province in southern China. Located on the Pearl River about north-northwest of Hong Kon ...

, and was the only member of Sun's inner circle to accompany him on trips outside of Kuomintang (KMT)-held territory in the months immediately preceding Sun's death. He is believed by many to have drafted Sun's will during the short period before Sun's death, in the winter of 1925. He was considered one of the main contenders to replace Sun as leader of the KMT, but eventually lost control of the party and army to Chiang Kai-shek. Wang had clearly lost control of the KMT by 1926, when, following the Zhongshan Warship Incident

The Canton Coup of 20 March 1926, also known as the or the was a purge of Communist elements of the Nationalist army in Guangzhou (then romanized as "Canton") undertaken by Chiang Kai-shek. The incident solidified Chiang's power immediate ...

, Chiang successfully sent Wang and his family to vacation in Europe. It was important for Chiang to have Wang away from Guangdong while Chiang was in the process of expelling communists from the KMT because Wang was then the leader of the left wing of the KMT, notably sympathetic to communists and communism, and may have opposed Chiang if he had remained in China.

Rivalry with Chiang Kai-shek

Leader of the Wuhan Government

During theNorthern Expedition

The Northern Expedition was a military campaign launched by the National Revolutionary Army (NRA) of the Kuomintang (KMT), also known as the "Chinese Nationalist Party", against the Beiyang government and other regional warlords in 1926. The ...

, Wang was the leading figure in the left-leaning faction of the KMT that called for continued cooperation with the Chinese Communist Party

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), officially the Communist Party of China (CPC), is the founding and One-party state, sole ruling party of the China, People's Republic of China (PRC). Under the leadership of Mao Zedong, the CCP emerged victoriou ...

. Although Wang collaborated closely with Chinese communists in Wuhan, he was philosophically opposed to communism and regarded the KMT's Comintern advisors with suspicion. He did not believe that Communists could be true patriots or true Chinese nationalists.

In early 1927, shortly before Chiang captured Shanghai and moved the capital to Nanjing, Wang's faction declared the capital of the Republic to be Wuhan

Wuhan (, ; ; ) is the capital of Hubei, Hubei Province in the China, People's Republic of China. It is the largest city in Hubei and the most populous city in Central China, with a population of over eleven million, the List of cities in China ...

. While attempting to direct the government from Wuhan, Wang was notable for his close collaboration with leading communist figures, including Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the founder of the People's Republic of China (PRC) ...

, Chen Duxiu

Chen Duxiu ( zh, t=陳獨秀, w=Ch'en Tu-hsiu; 8 October 187927 May 1942) was a Chinese revolutionary socialist, educator, philosopher and author, who co-founded the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) with Li Dazhao in 1921. From 1921 to 1927, he ser ...

, and Borodin

Alexander Porfiryevich Borodin ( rus, link=no, Александр Порфирьевич Бородин, Aleksandr Porfir’yevich Borodin , p=ɐlʲɪkˈsandr pɐrˈfʲi rʲjɪvʲɪtɕ bərɐˈdʲin, a=RU-Alexander Porfiryevich Borodin.ogg, ...

, and for his faction's provocative land reform policies. Wang later blamed the failure of his Wuhan government on its excessive adoption of communist agendas. Wang's regime was opposed by Chiang Kai-shek, who was in the midst of a bloody purge of communists in Shanghai and was calling for a push farther north. The separation between the governments of Wang and Chiang are known as the " Ninghan Separation" ().

Chiang Kai-shek occupied Shanghai in April 1927, and began a bloody suppression of suspected communists known as the "Shanghai Massacre

The Shanghai massacre of 12 April 1927, the April 12 Purge or the April 12 Incident as it is commonly known in China, was the violent suppression of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) organizations and leftist elements in Shanghai by forces supportin ...

". Within several weeks of Chiang's suppression of communists in Shanghai, Wang's leftist government was attacked by a KMT-aligned warlord and promptly disintegrated, leaving Chiang as the sole legitimate leader of the Republic. KMT troops occupying territories formerly controlled by Wang conducted massacres of suspected Communists in many areas: around Changsha

Changsha (; ; ; Changshanese pronunciation: (), Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is the capital and the largest city of Hunan Province of China. Changsha is the 17th most populous city in China with a population of over 10 million, an ...

alone, over ten thousand people were killed in a single twenty-day period. Fearing retribution as a communist sympathizer, Wang publicly claimed allegiance to Chiang before fleeing to Europe.Barnouin, Barbara and Yu Changgen. ''Zhou Enlai: A Political Life.'' Hong Kong: Chinese University of Hong Kong, 2006. p. 38. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

Political activities in Chiang's government

Between 1929 and 1930, Wang collaborated withFeng Yuxiang

Feng Yuxiang (; ; 6 November 1882 – 1 September 1948), courtesy name Huanzhang (焕章), was a warlord and a leader of the Republic of China from Chaohu, Anhui. He served as Vice Premier of the Republic of China from 1928 to 1930. He was ...

and Yan Xishan

Yan Xishan (; 8 October 1883 – 22 July 1960, ) was a Chinese warlord who served in the government of the Republic of China. He effectively controlled the province of Shanxi from the 1911 Xinhai Revolution to the 1949 Communist victory in ...

to form a central government in opposition to the one headed by Chiang. Wang took part in a conference hosted by Yan to draft a new constitution, and was to serve as the Prime Minister under Yan, who would be president. Wang's attempts to aid Yan's government ended when Chiang defeated the alliance in the Central Plains War

The Central Plains War () was a series of military campaigns in 1929 and 1930 that constituted a Chinese civil war between the Nationalist Kuomintang government in Nanjing led by Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek and several regional military command ...

.

In 1931, Wang joined another anti-Chiang government in Guangzhou. After Chiang defeated this regime, Wang reconciled with Chiang's Nanjing government and held prominent posts for most of the decade. Wang was appointed

In 1931, Wang joined another anti-Chiang government in Guangzhou. After Chiang defeated this regime, Wang reconciled with Chiang's Nanjing government and held prominent posts for most of the decade. Wang was appointed premier

Premier is a title for the head of government in central governments, state governments and local governments of some countries. A second in command to a premier is designated as a deputy premier.

A premier will normally be a head of governm ...

just as the Battle of Shanghai (1932) began. He had frequent disputes with Chiang and would resign in protest several times only to have his resignation rescinded. As a result of these power struggles within the KMT, Wang was forced to spend much of his time in exile. He traveled to Germany, and maintained some contact with Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

. As the leader of the Kuomintang's left-wing faction and a man who had been closely associated with Dr. Sun, Chiang wanted Wang as premier both to protect the "progressive" reputation of his government which was waging a civil war with the Communists and a shield for protecting his government from widespread public criticism of Chiang's policy of "first internal pacification, then external resistance" (i.e. first defeat the Communists, then confront Japan). Despite the fact that Wang and Chiang disliked and distrusted each other, Chiang was prepared to make compromises to keep Wang on as premier. In regards to Japan, Wang and Chiang differed in that Wang was extremely pessimistic about China's ability to win the coming war with Japan (which almost everyone in 1930s China regarded as inevitable) and was opposed to alliances with any foreign powers should the war come.

While being opposed to any effort at this time to subordinate China to Japan, Wang also saw the "white powers" like the Soviet Union, Britain and the United States as equal if not greater dangers to China, insisting that China had to defeat Japan solely by its own efforts if the Chinese were to hope to maintain their independence. But at the same time, Wang's belief that China was too economically backward at present to win a war against a Japan which had been aggressively modernizing since the Meiji Restoration of 1867 made him the advocate of avoiding war with Japan at almost any cost and trying to negotiate some sort of an agreement with Japan which would preserve China's independence. Chiang by contrast believed that if his modernization program was given enough time, China would win the coming war and that if the war came before his modernization plans were complete, he was willing to ally with any foreign power to defeat Japan, even including the Soviet Union, which was supporting the Chinese Communists in the civil war. Chiang was much more of a hardline anti-Communist than was Wang, but Chiang was also a self-proclaimed "realist" who was willing if necessary to have an alliance with the Soviet Union. Though in the short-run, Wang and Chiang agreed on the policy of "first internal pacification, then external resistance", in the long-run they differed as Wang was more of an appeaser while Chiang just wanted to buy time to modernize China for the coming war. The effectiveness of the KMT was constantly hindered by leadership and personal struggles, such as that between Wang and Chiang. In December 1935, Wang permanently left the premiership after being seriously wounded during an assassination attempt engineered a month earlier by

While being opposed to any effort at this time to subordinate China to Japan, Wang also saw the "white powers" like the Soviet Union, Britain and the United States as equal if not greater dangers to China, insisting that China had to defeat Japan solely by its own efforts if the Chinese were to hope to maintain their independence. But at the same time, Wang's belief that China was too economically backward at present to win a war against a Japan which had been aggressively modernizing since the Meiji Restoration of 1867 made him the advocate of avoiding war with Japan at almost any cost and trying to negotiate some sort of an agreement with Japan which would preserve China's independence. Chiang by contrast believed that if his modernization program was given enough time, China would win the coming war and that if the war came before his modernization plans were complete, he was willing to ally with any foreign power to defeat Japan, even including the Soviet Union, which was supporting the Chinese Communists in the civil war. Chiang was much more of a hardline anti-Communist than was Wang, but Chiang was also a self-proclaimed "realist" who was willing if necessary to have an alliance with the Soviet Union. Though in the short-run, Wang and Chiang agreed on the policy of "first internal pacification, then external resistance", in the long-run they differed as Wang was more of an appeaser while Chiang just wanted to buy time to modernize China for the coming war. The effectiveness of the KMT was constantly hindered by leadership and personal struggles, such as that between Wang and Chiang. In December 1935, Wang permanently left the premiership after being seriously wounded during an assassination attempt engineered a month earlier by Wang Yaqiao

Wang Yaqiao (; 2 September 1887 – 20 September 1936) was a Chinese gangster and assassin leader.

Biography

Wang was born Hefei, Anhui Province, to a country doctor. He was involved in socialist activism in his youth, which eventually brought ...

.

In 1936, Wang clashed with Chiang over foreign policy. In an ironic role reversal, the left-wing "progressive" Wang argued for accepting the German-Japanese offer of having China sign the Anti-Comintern Pact

The Anti-Comintern Pact, officially the Agreement against the Communist International was an anti-Communist pact concluded between Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan on 25 November 1936 and was directed against the Communist International (Com ...

while the right-wing "reactionary" Chiang wanted a rapprochement with the Soviet Union. During the 1936 Xi'an Incident

The Xi'an Incident, previously romanized as the Sian Incident, was a political crisis that took place in Xi'an, Shaanxi in 1936. Chiang Kai-shek, leader of the Nationalist government of China, was detained by his subordinate generals Chang Hs ...

, in which Chiang was taken prisoner by his own general, Zhang Xueliang

Chang Hsüeh-liang (, June 3, 1901 – October 15, 2001), also romanized as Zhang Xueliang, nicknamed the "Young Marshal" (少帥), known in his later life as Peter H. L. Chang, was the effective ruler of Northeast China and much of northern ...

, Wang favored sending a "punitive expedition" to attack Zhang. He was apparently ready to march on Zhang, but Chiang's wife, Soong Mei-ling

Soong Mei-ling (also spelled Soong May-ling, ; March 5, 1898 – October 23, 2003), also known as Madame Chiang Kai-shek or Madame Chiang, was a Chinese political figure who was First Lady of the Republic of China, the wife of Generalissimo and ...

, and brother-in-law, T. V. Soong

Soong Tse-vung, more commonly romanized as Soong Tse-ven or Soong Tzu-wen (; 4 December 1894 – 25 April 1971), was a prominent businessman and politician in the early 20th-century Republic of China, who served as Premier. His father was Char ...

, feared that such an action would lead to Chiang's death and his replacement by Wang, so they successfully opposed this action.

Wang accompanied the government on its retreat to Chongqing

Chongqing ( or ; ; Sichuanese dialects, Sichuanese pronunciation: , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ), Postal Romanization, alternately romanized as Chungking (), is a Direct-administered municipalities of China, municipality in Southwes ...

during the Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific Th ...

(1937–1945). During this time, he organized some right-wing groups along European fascist lines inside the KMT. Wang was originally part of the pro-war group; but, after the Japanese were successful in occupying large areas of coastal China, Wang became known for his pessimistic view on China's chances in the war against Japan.Cheng, Pei-Kai, Michael Lestz, and Jonathan D. Spence (Eds.) ''The Search for Modern China: A Documentary Collection'', W.W. Norton and Company. (1999) pp. 330–331. . He often voiced defeatist opinions in KMT staff meetings, and continued to express his view that Western imperialism was the greater danger to China, much to the chagrin of his associates. Wang believed that China needed to reach a negotiated settlement with Japan so that Asia could resist Western Powers.

Alliance with the Axis Powers

In late 1938, Wang left Chongqing for Hanoi, French Indochina, where he stayed for three months and announced his support for a negotiated settlement with the Japanese. During this time, he was wounded in an assassination attempt by KMT agents. Wang then flew to Shanghai, where he entered negotiations with Japanese authorities. The Japanese invasion had given him the opportunity he had long sought to establish a new government outside of Chiang Kai-shek's control.

On 30 March 1940, Wang became the head of state of what came to be known as the

In late 1938, Wang left Chongqing for Hanoi, French Indochina, where he stayed for three months and announced his support for a negotiated settlement with the Japanese. During this time, he was wounded in an assassination attempt by KMT agents. Wang then flew to Shanghai, where he entered negotiations with Japanese authorities. The Japanese invasion had given him the opportunity he had long sought to establish a new government outside of Chiang Kai-shek's control.

On 30 March 1940, Wang became the head of state of what came to be known as the Wang Jingwei regime

The Wang Jingwei regime or the Wang Ching-wei regime is the common name of the Reorganized National Government of the Republic of China ( zh , t = 中華民國國民政府 , p = Zhōnghuá Mínguó Guómín Zhèngfǔ ), the government of the pu ...

(formally "the Reorganized National Government of the Republic of China") based in Nanjing, serving as the President of the Executive Yuan and Chairman of the National Government (). In November 1940, Wang's government signed the "Sino-Japanese Treaty" with the Japanese, a document that has been compared with Japan's Twenty-one Demands

The Twenty-One Demands ( ja, 対華21ヶ条要求, Taika Nijūikkajō Yōkyū; ) was a set of demands made during the First World War by the Empire of Japan under Prime Minister Ōkuma Shigenobu to the government of the Republic of China on 18 ...

for its broad political, military, and economic concessions. In June 1941, Wang gave a public radio address from Tokyo in which he praised Japan and affirmed China's submission to it while criticizing the Kuomintang government, and pledged to work with the Empire of Japan to resist Communism and Western imperialism. Wang continued to orchestrate politics within his regime in concert with Chiang's international relationship with foreign powers, seizing the French Concession

The Shanghai French Concession; ; Shanghainese pronunciation: ''Zånhae Fah Tsuka'', group=lower-alpha was a foreign concession in Shanghai, China from 1849 until 1943, which progressively expanded in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Th ...

and the International Settlement of Shanghai

The Shanghai International Settlement () originated from the merger in the year 1863 of the British and American enclaves in Shanghai, in which British subjects and American citizens would enjoy extraterritoriality and consular jurisdiction ...

in 1943, after Western nations agreed by consensus to abolish extraterritoriality

In international law, extraterritoriality is the state of being exempted from the jurisdiction of local law, usually as the result of diplomatic negotiations.

Historically, this primarily applied to individuals, as jurisdiction was usually cla ...

.

The Government of National Salvation of the collaborationist "''Republic of China''", which Wang headed, was established on the Three Principles of Pan-Asianism

file:Asia satellite orthographic.jpg , Satellite photograph of Asia in orthographic projection.

Pan-Asianism (''also known as Asianism or Greater Asianism'') is an ideology aimed at creating a political and economic unity among Asian people, Asian ...

, anti-communism

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when the United States and the ...

, and opposition to Chiang Kai-shek. Wang continued to maintain his contacts with German Nazis

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

and Italian fascists he had established while in exile.Lifu Chen and Ramon Hawley Myers. ''The storm clouds clear over China: the memoir of Chʻen Li-fu, 1900–1993.'' p. 141. (1994)

Administration of the Wang Jingwei regime

Chinese under the regime had greater access to coveted wartime luxuries, and the Japanese enjoyed things like matches, rice, tea, coffee, cigars, foods, and alcoholic drinks, all of which were scarce in Japan proper, but consumer goods became more scarce after Japan entered World War II. In Japan-occupied Chinese territories, the prices of basic necessities rose substantially, as Japan's war effort expanded. In Shanghai in 1941, they increased elevenfold. Daily life was often difficult in the Nanjing Nationalist government-controlled Republic of China, and grew more so as the war turned against Japan (c. 1943). Local residents resorted to theblack market

A black market, underground economy, or shadow economy is a clandestine market or series of transactions that has some aspect of illegality or is characterized by noncompliance with an institutional set of rules. If the rule defines the se ...

to obtain needed items. The Japanese Kempeitai

The , also known as Kempeitai, was the military police arm of the Imperial Japanese Army from 1881 to 1945 that also served as a secret police force. In addition, in Japanese-occupied territories, the Kenpeitai arrested or killed those suspecte ...

, Tokko, collaborationist Chinese police, and Chinese citizens in the service of the Japanese all worked to censor information, monitor any opposition, and torture enemies and dissenters. A "native" secret agency, the '' Tewu'', was created with the aid of Japanese Army "advisors". The Japanese also established prisoner-of-war detention centers, concentration camps, and kamikaze

, officially , were a part of the Japanese Special Attack Units of military aviators who flew suicide attacks for the Empire of Japan against Allied naval vessels in the closing stages of the Pacific campaign of World War II, intending to d ...

training centers to indoctrinate pilots.

Since Wang's government held authority only over territories under Japanese military occupation, there was a limited amount that officials loyal to Wang could do to ease the suffering of Chinese under Japanese occupation. Wang himself became a focal point of anti-Japanese resistance. He was demonized and branded as an "arch-traitor" in both KMT and Communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

propaganda. Wang and his government were deeply unpopular with the Chinese populace, who regarded them as traitors to both the Chinese state and Han Chinese

The Han Chinese () or Han people (), are an East Asian ethnic group native to China. They constitute the world's largest ethnic group, making up about 18% of the global population and consisting of various subgroups speaking distinctive va ...

identity. Wang's rule was constantly undermined by resistance and sabotage.

The strategy of the local education system was to create a workforce suited for employment in factories and mines, and for manual labor in general. The Japanese also attempted to introduce their culture and dress to the Chinese. Complaints and agitation called for more meaningful Chinese educational development. Shinto

Shinto () is a religion from Japan. Classified as an East Asian religion by scholars of religion, its practitioners often regard it as Japan's indigenous religion and as a nature religion. Scholars sometimes call its practitioners ''Shintois ...

temples and similar cultural centers were built in order to instill Japanese culture and values. These activities came to a halt at the end of the war.

Death

In March 1944, Wang left for Japan to undergo medical treatment for the wound left by an assassination attempt in 1939. He died inNagoya

is the largest city in the Chūbu region, the fourth-most populous city and third most populous urban area in Japan, with a population of 2.3million in 2020. Located on the Pacific coast in central Honshu, it is the capital and the most pop ...

on 10 November 1944, less than a year before Japan's surrender to the Allies, thus avoiding a trial for treason. Many of his senior followers who lived to see the end of the war were executed. His death was not reported in occupied China until the afternoon of 12 November, after commemorative events for Sun Yat-sen's birth had concluded. Wang was buried in Nanjing near the Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum

Dr. Sun Yat-sen's Mausoleum () is situated at the foot of the second peak of Purple Mountain in Nanjing, China. Construction of the tomb started in January 1926, and was finished in spring of 1929. The architect was Lü Yanzhi, who died shortl ...

, in an elaborately constructed tomb. Soon after Japan's defeat, the Kuomintang government under Chiang Kai-shek moved its capital back to Nanjing, destroyed Wang's tomb, and burned the body. Today, the site is commemorated with a small pavilion that notes Wang as a traitor.

Legacy

For his role in thePacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War, was the theater of World War II that was fought in Asia, the Pacific Ocean, the Indian Ocean, and Oceania. It was geographically the largest theater of the war, including the vast ...

, Wang has been considered a traitor by most post-World War II Chinese historians in both Taiwan and mainland China. His name has become a byword for "traitor" or "treason" in mainland China and Taiwan, similarly to "Quisling

''Quisling'' (, ) is a term used in Scandinavian languages and in English meaning a citizen or politician of an occupied country who collaborates with an enemy occupying force – or more generally as a synonym for ''traitor''. The word ori ...

" in Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

, "Benedict Arnold

Benedict Arnold ( Brandt (1994), p. 4June 14, 1801) was an American military officer who served during the Revolutionary War. He fought with distinction for the American Continental Army and rose to the rank of major general before defect ...

" in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

, or "Mir Jafar

Sayyid Mīr Jaʿfar ʿAlī Khān Bahādur ( – 5 February 1765) was a military general who became the first dependent Nawab of Bengal of the British East India Company. His reign has been considered by many historians as the start of the expan ...

" in Bangladesh

Bangladesh (}, ), officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the eighth-most populous country in the world, with a population exceeding 165 million people in an area of . Bangladesh is among the mos ...

and South Asia. The mainland's communist government despised Wang not only for his collaboration with the Japanese, but also for his anti-communism, while the KMT downplayed his anti-communism and emphasized his collaboration with imperial Japan and betrayal of Chiang Kai-shek. The communists also used his ties with the KMT to demonstrate what they saw as the duplicitous, treasonous nature of the KMT. Both sides downplayed his earlier association with Sun Yat-sen because of his eventual collaboration.

Despite the notoriety added to his name, academics continue to discuss whether or not he should be unequivocally condemned as a traitor because Wang also contributed greatly to the Xinhai Revolution and to the later mediation between the Communist Party and the Nationalist Party in postwar China. They argue that Wang collaborated with the Japanese because he believed that collaboration was the only hope for his desperate countrymen.

Personal life

Wang was married toChen Bijun

Chen Bijun (, 5 November 1891 – 17 June 1959) was a Chinese politician. She was the acting head of the Canton (Guangzhou) government for four months in 1944–1945.Lily Xiao Hong Lee: Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women: v. 2: Twentieth C ...

and had six children with her, five of whom survived into adulthood. Of those who survived into adulthood, Wang's eldest son, Wenjin, was born in France in 1913. Wang's eldest daughter, Wenxing, was born in France in 1915, worked as a teacher in Hong Kong after 1948, retired to the US in 1984 and died in 2015. Wang's second daughter, Wang Wenbin, was born in 1920. Wang's third daughter, Wenxun, was born in Guangzhou in 1922 and died in 2002 in Hong Kong. Wang's second son, Wenti, was born in 1928 and was sentenced in 1946 to 18 months' imprisonment for being a '' hanjian''. After serving his sentence, Wang Wenti settled in Hong Kong and has been involved in many education projects with the mainland since the 1980s.

See also

* Huang Yiguang, and his assassination attempt on Wang Jingwei *Vidkun Quisling

Vidkun Abraham Lauritz Jonssøn Quisling (, ; 18 July 1887 – 24 October 1945) was a Norwegian military officer, politician and Nazi collaborator who nominally headed the government of Norway during the country's occupation by Nazi Germ ...

*Ye Wanyong

Ye Wan-yong (; 17 July 1858 – 12 February 1926), also spelled Yi Wan-yong or Lee Wan-yong ( ko, 이완용), was a Korean politician who served as the 7th Prime Minister of Korea. He was pro-Japanese and is best remembered for signing the J ...

*Anton Mussert

Anton may refer to: People

*Anton (given name), including a list of people with the given name

*Anton (surname)

Places

*Anton Municipality, Bulgaria

**Anton, Sofia Province, a village

*Antón District, Panama

**Antón, a town and capital of th ...

Notes

References

Further reading

*David P. Barrett and Larry N. Shyu, eds.; ''Chinese Collaboration with Japan, 1932–1945: The Limits of Accommodation'' Stanford University Press 2001. *Gerald Bunker, ''The Peace Conspiracy; Wang Ching-wei and the China war, 1937–1941 '' Harvard University Press, 1972. *James C. Hsiung and Steven I. Levine, eds. ''China's Bitter Victory: The War with Japan, 1937–1945'' M. E. Sharpe, 1992. *Ch'i Hsi-sheng, ''Nationalist China at War: Military Defeats and Political Collapse, 1937–1945'' University of Michigan Press, 1982. *Wen-Hsin Yeh, "Wartime Shanghai",Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. *Rana Mitter, "Forgotten Ally: China's World War II. 1937–1945" Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013. . Complete re-examination of the Chinese wars with Japan which argues that the memory of 'betrayals' by Britain, America, and Russia continues to influence China's worldview today. *Peter Kien-hong YU, Testing the Theory, WANG Jingwei Worked Under DAI Li, the Spymaster, https://www.storm.mg/article/3945430, dated September 19, 2021. Accused of Being a Big Traitor to China, Could WANG JingWei Be Rehabilitated?"Mainland China Studies Newsletter (Department of Political Science, National Taiwan University), No.135 (September 2020),pp. 7~20 and No.136 (December 2020), pp. 4~14. See also Chapter 2 and Appendix VII. WANG JingWei: A Talk About Some Labels That He Received (or Could Receive) During the March 1940 and November 1944 Period in ibid., Debunking Social Science and Confiding the _______ Theory (San Francisco: www.Academia.edu., January 2021), pages 151~160.(PDF) Debunking Social Science and Confiding the _______ Theory: Cheat and Last Cheat , peter k. h. yu - Academia.eduExternal links

*Japan's Asian Axis AlliesChinese National Government of Nanking

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Wang, Jingwei 1883 births 1944 deaths People from Sanshui District Chinese collaborators with Imperial Japan Kuomintang collaborators with Imperial Japan Chinese fascists Chinese people of World War II Chinese revolutionaries Failed assassins Foreign Ministers of the Republic of China Expelled members of the Kuomintang Traitors in history People of the Chinese Civil War Premiers of the Republic of China Presidents of the Republic of China World War II political leaders Republic of China politicians from Guangdong Chinese anti-communists Chinese nationalists Tongmenghui members Chinese expatriates in France People of the Northern Expedition Fascist rulers Politicians from Foshan