Walter Buch on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Walter Buch (24 October 1883 – 12 September 1949) was a German

Near the end of the war in Europe, Buch was arrested by American forces on 30 April 1945. He was categorized as a “major offender” by a

Near the end of the war in Europe, Buch was arrested by American forces on 30 April 1945. He was categorized as a “major offender” by a

jurist

A jurist is a person with expert knowledge of law; someone who analyses and comments on law. This person is usually a specialist legal scholar, mostly (but not always) with a formal qualification in law and often a legal practitioner. In the Uni ...

as well as an SA and SS official during the Nazi era

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

. He was Martin Bormann

Martin Ludwig Bormann (17 June 1900 – 2 May 1945) was a German Nazi Party official and head of the Nazi Party Chancellery. He gained immense power by using his position as Adolf Hitler's private secretary to control the flow of information ...

's father-in-law. As head of the Supreme Party Court, he was an important Party official. However due to his insistence on prosecuting major Party figures on moral issues, he alienated Adolf Hitler and his power and influence gradually diminished into insignificance. After the end of the Second World War in Europe, Buch was classified as a major regime functionary or in the denazification

Denazification (german: link=yes, Entnazifizierung) was an Allied initiative to rid German and Austrian society, culture, press, economy, judiciary, and politics of the Nazi ideology following the Second World War. It was carried out by remov ...

proceedings in 1948. On 12 September of 1949, he committed suicide.

Early life and career

Born in Bruchsal, the son of a Senate President at the Baden High Court, Buch graduated from the gymnasium in Konstanz and entered military service in 1902 as an officer cadet. He became a career officer in theImperial German Army

The Imperial German Army (1871–1919), officially referred to as the German Army (german: Deutsches Heer), was the unified ground and air force of the German Empire. It was established in 1871 with the political unification of Germany under the l ...

and served in the First World War as a training officer and a company commander, earning the Iron Cross 1st and 2nd class. In 1918, he was released from the army as a Major

Major (commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicators ...

when he refused to swear allegiance to the new Weimar Republic. He was then active in the Baden Veterans' League. From 1919 to 1922 he was a member of the German National People's Party (DNVP/Deutschnationale Volkspartei). During these years he was also a member of the , the largest, most active, and most influential anti-Semitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

federation in Germany

By December 1922, he had become a member of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) attracted by its virulent anti-semitism. He became the (Local Group Leader) in Karlsruhe and joined the (SA) in January 1923. By August of that year he was leader of the SA in Franconia. In mid-1923, the (Shock Troop-Hitler) which consisted of eight SA members was formed for Hitler's personal protection. Buch was recruited as a member of this SS-forerunner organization.

Buch participated in the Beer Hall Putsch

The Beer Hall Putsch, also known as the Munich Putsch,Dan Moorhouse, ed schoolshistory.org.uk, accessed 2008-05-31.Known in German as the or was a failed coup d'état by Nazi Party ( or NSDAP) leader Adolf Hitler, Erich Ludendorff and othe ...

on 9 November 1923 and eluded capture as many other SA leaders fled the country. Buch came back to Munich as early as 13 November, sent by Hermann Göring – who had fled to Innsbruck

Innsbruck (; bar, Innschbruck, label=Bavarian language, Austro-Bavarian ) is the capital of Tyrol (state), Tyrol and the List of cities and towns in Austria, fifth-largest city in Austria. On the Inn (river), River Inn, at its junction with the ...

– to ensure that the shaken Party troops' cohesion would not weaken. He built up ties with the now outlawed SA groups, which could now only operate undercover and briefly was charged with the leadership of the outlawed SA until arrested in February 1924. Buch maintained regular contact between Hitler, who was incarcerated in Landsberg prison, and the illegal Party leadership in Austria. In the time that followed, when the NSDAP was banned, Göring's fears began to come true as the party broke up. After Hitler was released from Landsberg in December 1924, he reestablished the Party on 27 February 1925. Buch soon rejoined, becoming the SA leader in Munich and serving in that capacity until November 1927.

Chairman of the Supreme Party Court

The Inquiry and Mediation Committee (''Untersuchungs- und Schlichtungs-Ausschuss'' or USCHLA), had been established in December 1925 by Hitler to settle intra-party problems and disputes. On 27 November 1927, Hitler named Buch Acting Chairman of this body (permanent Chairman as of 1 January 1928). The USCHLA's headquarters were at the Brown House, Munich. In addition to the national organization, there were lower level USCHLA components at the Local and Gau levels. Their decisions could be appealed to the national USCHLA which specifically had the right to cite “higher Party reasons” as the sole justification for refusing to accept a lower level decision. Hitler used this to wield almost total control over intra-Party disputes. Buch did not have any formal legal training and tried to avoid choosing professional lawyers as Party judges, preferring to rely on old Party stalwarts (''Alter Kämpfer

''Alter Kämpfer'' ( German for "Old Fighter"; plural: ''Alte Kämpfer'') is a term referring to the earliest members of the Nazi Party, i.e. those who joined it before the ''Reichstag'' 1930 German federal election, with many belonging to the p ...

'') because he trusted them to share his outlook for the Party. The two other USCHLA members at the time of Buch's becoming chairman were Hans Frank and Ulrich Graf.

Following the Nazi seizure of power

Adolf Hitler's rise to power began in the newly established Weimar Republic in September 1919 when Hitler joined the '' Deutsche Arbeiterpartei'' (DAP; German Workers' Party). He rose to a place of prominence in the early years of the party. Be ...

, the USCHLA was renamed the Supreme Party Court (''Oberste Parteigericht'') on 1 January 1934. Buch was retained as its Chairman and also given the title of ''Oberster Parteirichter'' (Supreme Party Judge). The Court was empowered to conduct investigations, render judgments and take disciplinary actions against Party members. It could only impose sanctions that affected the accused’s relationship with the Party. The punishments could range from reprimand, to dismissal from Party offices and to the most extreme punishment, expulsion from the Party. If a case involved any criminal activity, the Court would refer the case to the criminal courts for action. However, any pronouncements of the Court were not binding on the criminal courts. The Court needed the concurrence of Hitler to effectuate its decisions, which at times he refused to grant.

In 1934, Buch described the importance of Party tribunals thus:

The Party tribunals always have themselves to consider as the iron fasteners that hold together the proud building of the Nazi Party, which political leaders and SA leaders have built up. Saving it from cracks and shocks is the Party tribunals' grandest task. The Party magistrates are bound only to their National Socialist conscience, and are no political leader's subordinates, and they are subject only to the Führer.Buch acted in accordance with this belief in the purge of the SA leadership following the Night of the Long Knives in June 1934. Having amassed evidence against SA-'' Stabschef''

Ernst Röhm

Ernst Julius Günther Röhm (; 28 November 1887 – 1 July 1934) was a German military officer and an early member of the Nazi Party. As one of the members of its predecessor, the German Workers' Party, he was a close friend and early ally ...

and his colleagues by gathering complaints about homosexual activities among SA members, Buch traveled at Hitler's behest to Bad Wiessee

Bad Wiessee (Central Bavarian: ''Bad Wiessä'') is a municipality in the district of Miesbach in Upper Bavaria in Germany. Since 1922, it has been a spa town and located on the western shore of the Tegernsee Lake. It had a population of around ...

and was present at Röhm's arrest. Buch felt that Röhm and his fellow SA leaders should have faced the Supreme Party Court and was not informed of their summary execution

A summary execution is an execution in which a person is accused of a crime and immediately killed without the benefit of a full and fair trial. Executions as the result of summary justice (such as a drumhead court-martial) are sometimes include ...

s until after the fact. However, Buch’s courts at all levels were very active in the subsequent extensive purge of SA personnel throughout the Reich. Buch reminded the tribunals that it was their duty to serve the Party, not “objective truth.” There are no accurate figures on the numbers of those expelled from the Party in the widespread purge, but they included members of the political organization as well as the SA.

Buch believed that National Socialism should foster a revolution in morality as well as in politics, and he sought to use his position to spearhead a crusade against vice and corruption. Buch did not confine himself merely to ruling in internal Party disputes, but also had Party members investigated or sanctioned for personal moral failings. Buch felt that marital fidelity and family stability were cornerstones of National Socialism. He often demanded punishment for moral offenses by senior Party leaders. These moral crusades earned him many enemies among his Party colleagues, including powerful '' Gauleiters'' such as Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazi politician who was the ''Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief propagandist for the Nazi Party, and then Reich Minister of Propaganda from 1933 to 19 ...

, Julius Streicher and Wilhelm Kube. In addition, Hitler had no strong reservations about leaders’ private lives so long as they remained personally loyal and avoided open scandal. As a consequence, Buch’s influence in the Party began to ebb, as can be demonstrated by several high profile cases against leading Party figures:

• In late 1935, the ''Gauleiter'' of Kurmark

The German term ''Kurmark'' (archaic ''Churmark'', "Electoral March") referred to the Imperial State held by the margraves of Brandenburg, who had been awarded the electoral (''Kur'') dignity by the Golden Bull of 1356. In early modern times, ''K ...

, Wilhelm Kube, began an affair with his secretary, impregnated her and began divorce proceedings against his wife. Buch was outraged by these actions and scolded the ''Gauleiter'' in writing for his adulterous affair and for tolerating similar behavior by his subordinates. The Party Court began an investigation into allegations of corruption, favoritism and nepotism

Nepotism is an advantage, privilege, or position that is granted to relatives and friends in an occupation or field. These fields may include but are not limited to, business, politics, academia, entertainment, sports, fitness, religion, an ...

in his management of the Gau and issued a stern reprimand. However, Hitler was reluctant to remove one of his old comrades and summoned Buch to the Reich Chancellery for a personal rebuke on 14 November. Then in April 1936, an anonymous letter charged that Buch's wife was half-Jewish

"Who is a Jew?" ( he, מיהו יהודי ) is a basic question about Jewish identity and considerations of Jewish self-identification. The question pertains to ideas about Jewish personhood, which have cultural, ethnic, religious, political, ...

. In the course of a Gestapo investigation, it came to light that the letter had been written by Kube, in an attempt to get revenge on Buch. The Supreme Party Court issued an official reprimand in August 1936 and removed Kube from all his posts. Only on Hitler's orders was Kube allowed to retain the rank and uniform of an “honorary” ''Gauleiter''. This whole sordid affair did nothing to restore Buch to Hitler’s good graces.

• Buch was also responsible for the whitewashing of Party members' excesses during the nationwide '' Kristallnacht'' pogrom of 9 November 1938. Only 30 Party members were charged and most all had their cases dismissed or were given mild punishments. Buch’s report, issued in February 1939, declared that the killings that had taken place were “committed on the basis of a vague or presumed order … but motivated by hatred against Jews … rmotivated by a resolution suddenly formed in the excitement of the moment.” He refused to hold the defendants responsible for following orders. However, his naming of Reichsminister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazi politician who was the ''Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief propagandist for the Nazi Party, and then Reich Minister of Propaganda from 1933 to 19 ...

as the instigator of the “vague order” further alienated Buch from the Nazi leadership.

• In early 1940, Buch began proceedings against Julius Streicher, the ''Gauleiter'' of Gau Franconia

Gau Franconia (German: ''Gau Franken'') was an administrative division of Nazi Germany in Middle Franconia, Bavaria, from 1933 to 1945. Before that, from 1929 to 1933, it was the regional subdivision of the Nazi Party in that area. Originally fo ...

for behavior viewed as so irresponsible that he was embarrassing the party leadership. He was accused of keeping Jewish property seized after ''Kristallnacht''; of spreading untrue stories about Hermann Göring – alleging that he was impotent and that his daughter Edda was conceived by artificial insemination; and of immoral personal behavior, including open adultery. He was brought before the Supreme Party Court and on 16 February 1940 was judged to be "unsuitable for leadership" and stripped of his party offices. However, Hitler considered Streicher one of his oldest and most loyal comrades. He considered overturning the verdict and removing “the old fool” Buch but, in the end, he settled for permitting Streicher to retain the title of ''Gauleiter'' and to continue as the publisher of '' Der Stürmer''. This episode further strained Buch’s relationship with Hitler.

• In November 1941, Hitler dismissed the ''Gauleiter'' of Gau Westphalia-South, Josef Wagner, from his position and ordered that he face the Supreme Party Court. Wagner was charged with ideological deviation, by remaining in the Catholic Church and sending his children to convent school. In addition, his wife objected to the marriage of their daughter to an SS member. Wagner defended himself ably and, in February 1942, the Court exonerated him. Hitler angrily refused to ratify the Court’s decision and, responding to this high level rebuke, the Court was finally compelled to expel Wagner from the Party in October 1942.

After this latest episode Hitler resolved to act against Buch and, at the end of November 1942, Buch lost what powers still remained to him. Hitler decreed that the Court could no longer try cases involving ideological issues. In addition, ''Gauleiters'' were authorized to serve as courts of appeal for Party courts at the Gau level and Hitler delegated the power of confirming the Supreme Party Court’s decisions to the Chief of the Nazi Party Chancellery

The Party Chancellery (german: Parteikanzlei), was the name of the head office for the German Nazi Party (NSDAP), designated as such on 12 May 1941. The office existed previously as the Staff of the Deputy Führer (''Stab des Stellvertreters des ...

, Martin Bormann

Martin Ludwig Bormann (17 June 1900 – 2 May 1945) was a German Nazi Party official and head of the Nazi Party Chancellery. He gained immense power by using his position as Adolf Hitler's private secretary to control the flow of information ...

. Bormann incidentally was married to Buch's daughter Gerda, but was not on good terms with Buch. Bormann from then on at times nullified sentences pronounced by the Court and at other times interfered with its deliberations, indicating what decision he expected of it. Buch tried to maintain his independence of action but eventually refused to preside over Court sessions and effectively withdrew from his position. In post-war interrogations, he claimed to have offered to resign and join the army several times during the Second World War but that his offers were never accepted.

Other positions

Apart from his leadership of the Supreme Party Court, Buch held several other high level positions in the Nazi Party and government. On 20 May 1928, Buch was elected from electoral constituency 24 (Upper Bavaria-Swabia) as one of the first 12 Nazi Party deputies to the '' Reichstag''. He would subsequently be elected from constituencies 15 (East Hanover) in 1933 and 29 ( Leipzig) in 1936, and would serve continuously until the end of the Nazi regime. Buch served as the leader of the Youth Office (''Jugendamt'') in the Party’s national leadership (''Reichsleitung'') from June 1930 until 30 October 1931 when he was succeeded byBaldur von Schirach

Baldur Benedikt von Schirach (9 May 1907 – 8 August 1974) was a German politician who is best known for his role as the Nazi Party national youth leader and head of the Hitler Youth from 1931 to 1940. He later served as ''Gauleiter'' and ''Re ...

. On 18 December 1931, Buch was promoted to SA-''Gruppenführer

__NOTOC__

''Gruppenführer'' (, ) was an early paramilitary rank of the Nazi Party (NSDAP), first created in 1925 as a senior rank of the SA. Since then, the term ''Gruppenführer'' is also used for leaders of groups/teams of the police, fire de ...

''. He also served for a time up to 1933 as an editor at the Party newspaper ''Völkische Beobachter

The German noun ''Volk'' () translates to people,

both uncountable in the sense of ''people'' as in a crowd, and countable (plural ''Völker'') in the sense of '' a people'' as in an ethnic group or nation (compare the English term ''folk'') ...

''. On 2 June 1933, he was appointed by Hitler as a ''Reichsleiter

' (national leader or Reich leader) was the second-highest political rank of the Nazi Party (NSDAP), next only to the office of ''Führer''. ''Reichsleiter'' also served as a paramilitary rank within the NSDAP and was the highest position attaina ...

'', the second highest political rank in the Nazi Party. On 1 July 1933, Buch joined the '' Schutzstaffel'' (SS) and became an Honorary Leader ''(Ehrenführer)'' with the rank of SS-''Gruppenführer''; he would be promoted to SS-'' Obergruppenführer'' on 9 November 1934. On 1 April 1936 he was appointed to the staff of Heinrich Himmler, the '' Reichsführer-SS''. On 3 October 1934, he was made a member of the Academy for German Law.

Imprisonment and suicide

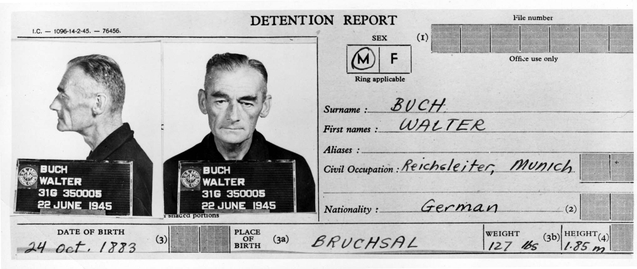

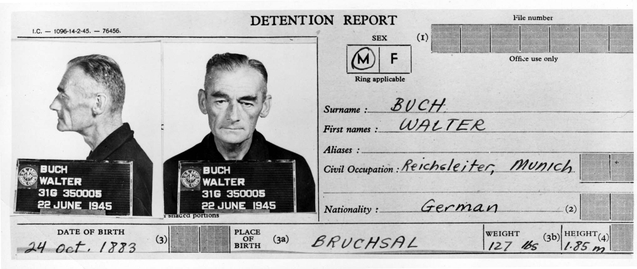

Near the end of the war in Europe, Buch was arrested by American forces on 30 April 1945. He was categorized as a “major offender” by a

Near the end of the war in Europe, Buch was arrested by American forces on 30 April 1945. He was categorized as a “major offender” by a denazification

Denazification (german: link=yes, Entnazifizierung) was an Allied initiative to rid German and Austrian society, culture, press, economy, judiciary, and politics of the Nazi ideology following the Second World War. It was carried out by remov ...

court on 3 July 1948 and sentenced to five years in a labor camp

A labor camp (or labour camp, see spelling differences) or work camp is a detention facility where inmates are forced to engage in penal labor as a form of punishment. Labor camps have many common aspects with slavery and with prisons (especi ...

. An appeal on 29 July 1949 reaffirmed his status as a major offender but reduced his sentence to three and a half years and he was released on the basis of time served. A few weeks after his release from prison, on 12 September 1949, he ended his own life by slitting his wrists and throwing himself into the Ammersee

Ammersee (English: Lake Ammer) is a Zungenbecken lake in Upper Bavaria, Germany, southwest of Munich between the towns of Herrsching and Dießen am Ammersee. With a surface area of approximately , it is the sixth largest lake in Germany. The lake ...

. (''Langener Zeitung'', 16 September 1949)

Decorations and awards

* Iron Cross 2nd Class * Iron Cross 1st Class * Nuremberg Party Day Badge, 1929 * Honour Chevron for the Old Guard, February 1934 * The Honour Cross of the World War 1914/1918 with Swords, 1934 *Coburg Badge

The Coburg Badge (''Das Coburger Abzeichen'') was the first badge recognised as a national award of the Nazi Party (NSDAP).

History

On 14 October 1922 Adolf Hitler led 800 members of the SA from Munich and other Bavarian cities by train to Cobur ...

, 1935

* Blood Order

The Blood Order (german: Blutorden), officially known as the "Decoration in Memory (of the Munich putsch) of 9 November 1923" (), was one of the most prestigious decorations in the Nazi Party (NSDAP). During March 1934, Hitler authorized the ...

(Commemorative Medal of the 9th of November 1923)

References

Bibliography

* * * *External links

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Buch, Walter 1883 births 1949 suicides Christian fascists German National People's Party politicians German nationalists German newspaper editors German Protestants Holocaust perpetrators in Germany Martin Bormann Members of the Academy for German Law Members of the Reichstag of Nazi Germany Members of the Reichstag of the Weimar Republic Nazi Party officials Nazi Party politicians Nazi propagandists Nazis who committed suicide in Germany Nazis who participated in the Beer Hall Putsch People from Bruchsal People from the Grand Duchy of Baden Recipients of the Iron Cross (1914), 1st class Recipients of the Iron Cross (1914), 2nd class Reichsleiters SS-Obergruppenführer Sturmabteilung officers German Army personnel of World War I