Walter Breisky on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Walter Breisky (8 July 1871 – 25 September 1944) was an

Breisky was no ideologue and felt no instinctive allegiance to any of the republic's three dominant political camps. A scion of the upper class and socially conservative by temperament, Breisky was certainly no

Breisky was no ideologue and felt no instinctive allegiance to any of the republic's three dominant political camps. A scion of the upper class and socially conservative by temperament, Breisky was certainly no

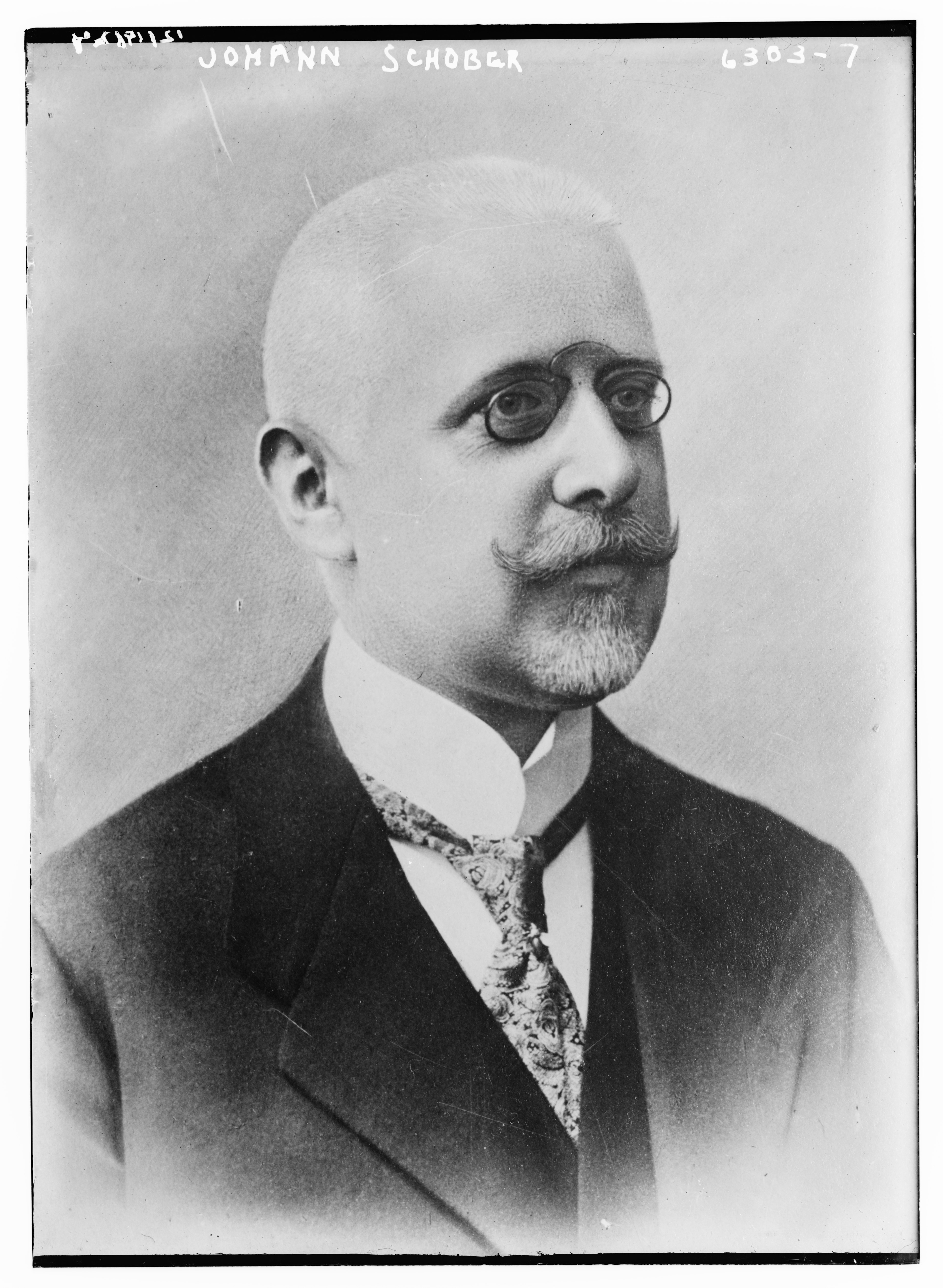

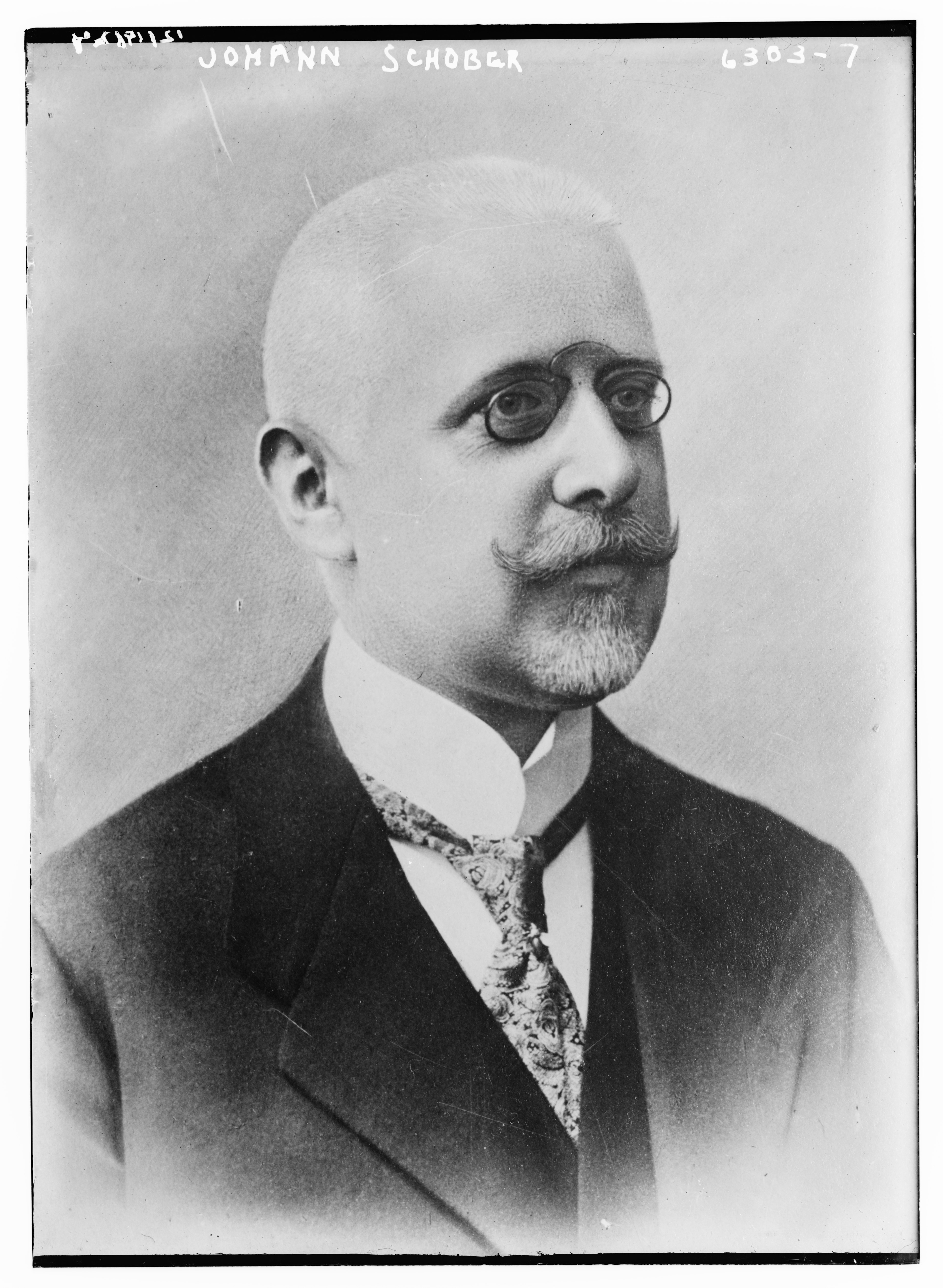

On 16 December 1921 Chancellor Schober and

On 16 December 1921 Chancellor Schober and

Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

n jurist

A jurist is a person with expert knowledge of law; someone who analyses and comments on law. This person is usually a specialist legal scholar, mostly (but not always) with a formal qualification in law and often a legal practitioner. In the Un ...

, civil servant, and politician

A politician is a person active in party politics, or a person holding or seeking an elected office in government. Politicians propose, support, reject and create laws that govern the land and by an extension of its people. Broadly speaking, a ...

.

Nominated by the Christian Social Party, Breisky served as minister of education and the interior from July to November 1920, as the vice chancellor

A chancellor is a leader of a college or university, usually either the executive or ceremonial head of the university or of a university campus within a university system.

In most Commonwealth and former Commonwealth nations, the chancellor i ...

and state secretary of education from November 1920 to May 1922.

Together with his Social Democratic

Social democracy is a Political philosophy, political, Social philosophy, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports Democracy, political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocati ...

deputy, Otto Glöckel, Breisky initiated sweeping reforms of Austria's education system.

In January 1922, Breisky became the caretaker chancellor of Austria

The chancellor of the Republic of Austria () is the head of government of the Republic of Austria. The position corresponds to that of Prime Minister in several other parliamentary democracies.

Current officeholder is Karl Nehammer of the A ...

for a single day.

Early life

Walter Breisky was born on 8 July 1871 in Bern, Switzerland. He was the second son of August Breisky and Pauline Breisky, née von Less. Both parents were of Bohemian descent. The family was living in Switzerland at the time of Breisky's birth because his father, a noted physician, had accepted a professorship ofgynecology

Gynaecology or gynecology (see spelling differences) is the area of medicine that involves the treatment of women's diseases, especially those of the reproductive organs. It is often paired with the field of obstetrics, forming the combined ar ...

at the University of Bern

The University of Bern (german: Universität Bern, french: Université de Berne, la, Universitas Bernensis) is a university in the Swiss capital of Bern and was founded in 1834. It is regulated and financed by the Canton of Bern. It is a compreh ...

in 1867. When August Breisky was invited to assume a chair at the University of Prague in 1874, the family moved back home.

In Prague, Breisky attended elementary school and received the first four years of his gymnasium education. In 1886, his father was offered a position with the Second Gynecological Clinic of the University of Vienna

The University of Vienna (german: Universität Wien) is a public research university located in Vienna, Austria. It was founded by Duke Rudolph IV in 1365 and is the oldest university in the German-speaking world. With its long and rich h ...

. Breisky thus completed his secondary education in the imperial capital, graduating from the high-profile Gymnasium Wasagasse

The Gymnasium Wasagasse (''Bundesgymnasium Wien IX'', in short ''BG9'') is a secondary school in Alsergrund, the 9th district of Vienna. Alumni of the school include two Nobel laureates, an Academy Award winner and many notable politicians, artis ...

in 1890. Shortly before Breisky could finish school, his father died, a loss that appears to have hit teenaged Breisky hard. Since Breisky was not yet of age, his uncle, Rudolf Baron Breisky, became his legal guardian and eventually adopted him. Baron Breisky was a senior official in the Ministry of the Interior

An interior ministry (sometimes called a ministry of internal affairs or ministry of home affairs) is a government department that is responsible for internal affairs.

Lists of current ministries of internal affairs

Named "ministry"

* Ministr ...

; he had served as the head of the ministry's presidium for 25 years and was one of the closest collaborators of Interior Minister Eduard Taaffe

Eduard Franz Joseph Graf von Taaffe, 11th Viscount Taaffe (24 February 183329 November 1895) was an Austrian statesman, who served for two terms as Minister-President of Cisleithania, leading cabinets from 1868 to 1870 and 1879 to 1893. He was a ...

. It is likely that Baron Breisky encouraged his ward to pursue a career in the imperial bureaucracy. Austrian diplomat Michael Breisky

Michael Breisky (born 29 December 1940 in Lisbon) is a former Austrian diplomat and, as a Anti-globalization movement, globalization critic, is the author of numerous publications on Leopold Kohr and his teaching.

Breisky family

The Breisky fami ...

is his grandnephew.

Breisky's grades appeared to suggest that his talents lay more in the humanities than in any technical fields. Breisky enrolled at the University of Vienna

The University of Vienna (german: Universität Wien) is a public research university located in Vienna, Austria. It was founded by Duke Rudolph IV in 1365 and is the oldest university in the German-speaking world. With its long and rich h ...

to study law and political science. He graduated with distinction in 1895.

Career

Civil servant

Within ten days of graduating from university, Breisky secured employment as an apprentice clerk () in the governor's office () of the Archduchy of Lower Austria. It is unlikely that Breisky owed his swift admission into the civil service to his uncle's patronage. Walter Breisky was chosen for the position by Minister-President Erich Graf von Kielmannsegg, who intensely disliked Rudolf Baron Breisky for the latter's personality; in Kielmannsegg's autobiography, Baron Breisky would be described as a "supercilious fossil". In spite of the enmity between guardian and superior, Breisky rose through the ranks with ease and remarkable speed. In 1895, he was assigned to theKorneuburg

Korneuburg () is a town in Austria. It is located in the state Lower Austria and is the administrative center of the district of Korneuburg. Korneuburg is situated on the left bank of the Danube, opposite the city of Klosterneuburg, and is 12&n ...

precinct administration. Three years later, he was promoted from apprentice clerk to regular clerk () and appointed to the executive committee of the state bureaucracy. His performance reviews were consistently glowing.

On 1 January 1900, Breisky was reassigned to the Ministry of Education

An education ministry is a national or subnational government agency politically responsible for education. Various other names are commonly used to identify such agencies, such as Ministry of Education, Department of Education, and Ministry of Pub ...

. Employment in the ministerial bureaucracy was significantly more prestigious than employment in a state administration, and Breisky was still only 28 years old, unusually young for advancement to the ministry.

The step up in rank was all the more remarkable as Breisky was a Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

, a serious handicap in the Habsburg bureaucracy in general and in the Ministry of Education in particular. In 1905, the Ministry tried to get rid of the religious outsider by offering him to fill a vacancy on the Evangelical Church Council. The move would have advanced Breisky by an additional two steps in rank. Breisky declined.

Breisky's refusal to accept the sinecure did no permanent damage to his career. In April 1907, Breisky was appointed to the ministry's presidium. In February 1908, he was promoted to ministerial secretary (); he subsequently became a noted collaborator of Minister-President Baron Max Wladimir von Beck. The two men grew very close, to the point of spending extended holidays together. In 1909, Breisky received the job title of departmental advisor (). In 1913, he was made a ministerial advisor ().

The collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with t ...

at the end of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

was a serious personal blow to Breisky, who was 47 years old now and had spent his entire working life as a loyal servant of the Habsburg Monarchy. In spite of his despondency, Breisky remained at his post. The emerging Republic of German-Austria

The Republic of German-Austria (german: Republik Deutschösterreich or ) was an unrecognised state that was created following World War I as an initial rump state for areas with a predominantly German-speaking and ethnic German population wit ...

knew to appreciate his experience. In May 1919, Breisky was made a department director () in the Chancellery (), personal bureau of Chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

Karl Renner

Karl Renner (14 December 1870 – 31 December 1950) was an Austrian politician and jurist of the Social Democratic Workers' Party of Austria. He is often referred to as the "Father of the Republic" because he led the first government of German- ...

and heart of the rump state's executive apparatus. Once again, Breisky became a close confidant and trusted lieutenant of the chief executive. Renner instructed his staff that every document addressed to Renner should also be made available to Breisky, preferably before Renner himself had seen it.

Minister of education

Breisky was no ideologue and felt no instinctive allegiance to any of the republic's three dominant political camps. A scion of the upper class and socially conservative by temperament, Breisky was certainly no

Breisky was no ideologue and felt no instinctive allegiance to any of the republic's three dominant political camps. A scion of the upper class and socially conservative by temperament, Breisky was certainly no Social Democrat

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote soc ...

, his harmonious working relationship with Renner nonwithstanding. The Christian Social camp shared his traditionalism but was also explicitly Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

. His Evangelical

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide interdenominational movement within Protestant Christianity that affirms the centrality of being " born again", in which an individual exp ...

faith would have pointed him to the German Nationalists, also socially conservative. A descendant of a family of Habsburg civil servants and a lifelong Habsburg civil servant himself, however, would not have felt drawn to a camp that defined itself as pan-German and as Antisemitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Ant ...

besides.

Even so, Breisky eventually entered formal politics.

In July 1920, the Social Democratic Party

The name Social Democratic Party or Social Democrats has been used by many political parties in various countries around the world. Such parties are most commonly aligned to social democracy as their political ideology.

Active parties

Fo ...

, Christian Social Party, and Greater German People's Party

The Greater German People's Party (German language, German ''Großdeutsche Volkspartei'', abbreviated GDVP) was a German nationalism in Austria, German nationalist and National liberalism, national liberal List of political parties in Austria, po ...

agreed to form a national unity government

A national unity government, government of national unity (GNU), or national union government is a broad coalition government consisting of all parties (or all major parties) in the legislature, usually formed during a time of war or other na ...

to manage the transition from provisional to permanent constitution that was in progress at the time. The Christian Socials offered to make Breisky head of the Ministry of Education

An education ministry is a national or subnational government agency politically responsible for education. Various other names are commonly used to identify such agencies, such as Ministry of Education, Department of Education, and Ministry of Pub ...

. Breisky accepted.

On 7 July Breisky was sworn in as a state secretary – the term for "minister" in the provisional constitution – of education in the first Mayr government.

The deputy state secretary of education under both Renner and Mayr was Otto Glöckel, a Social Democrat

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote soc ...

and committed progressive. Glöckel was driving an ambitious program of education reform that included both structural reorganization and a drastic changes to the system's pedagogical approach. Traditionally, children were sorted into different educational tracks after graduating from elementary school at age ten. In theory, the sorting criteria were scholastic aptitude and talent profile; in practice, students were sorted by socioeconomic background. Glöckel meant to help break down class barriers through merging the different types of middle schools, thus delaying the sorting for another four years. In terms of style, education was to focus on inspiring self-reliance and independent thought as opposed to rote learning.

Glöckel's new superior, no revolutionary but open to new ideas, halted some of Glöckel's reforms but happily embraced others, then added reform ideas of his own.

He promoted access to education for girls

Female education is a catch-all term of a complex set of issues and debates surrounding education (primary education, secondary education, tertiary education, and health education in particular) for girls and women. It is frequently called girl ...

, worked to improve teacher training, professionalized the textbook approbation process, overhauled the school physicians' service, and modernized curricula.

He also worked to improve access to education, and to the arts

The arts are a very wide range of human practices of creative expression, storytelling and cultural participation. They encompass multiple diverse and plural modes of thinking, doing and being, in an extremely broad range of media. Both h ...

and humanities

Humanities are academic disciplines that study aspects of human society and culture. In the Renaissance, the term contrasted with divinity and referred to what is now called classics, the main area of secular study in universities at th ...

in particular, for children in rural regions. While Vienna was a vibrant metropolis and a global cultural center for music and theater, large parts of the rest of Austria were a backwater. Breisky took the initiative in organizing concerts and theatrical performances for the sons and daughters of the hinterland.

When the Social Democrats left the unity government on 22 October, the post of minister of defense – now actually called "minister" because the new constitution had entered into force – became vacant. Breisky was appointed acting minister. When the second Mayr government took office on 20 November, Breisky became vice chancellor

A chancellor is a leader of a college or university, usually either the executive or ceremonial head of the university or of a university campus within a university system.

In most Commonwealth and former Commonwealth nations, the chancellor i ...

. The Ministry of Education had been merged into the Ministry of the Interior, and the combined ministry was lead not by Breisky but by Egon Glanz. Breisky, however, was made the state secretary – the term now meant "deputy minister" – in charge of education affairs, retaining his previous portfolio and continuing his reform work. When Glanz resigned on 7 April 1921 Breisky was promoted to acting minister. On 21 June the first Schober government

In Austrian politics, the first Schober government (german: Regierung Schober I) was a short-lived coalition government led by Johannes Schober, in office from June 21, 1921 to January 26, 1922. Although the coalition, consisting of the Christia ...

was inaugurated; this cabinet too included Breisky as both vice chancellor and state secretary of education.

Chancellor for a day

On 16 December 1921 Chancellor Schober and

On 16 December 1921 Chancellor Schober and President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese f ...

Hainisch signed the Treaty of Lana, an agreement of mutual understanding and friendship between Austria and Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

. In particular, Austria reconfirmed to its neighbor to the north that it would faithfully abide by the Treaty of Saint-Germain

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal pers ...

and would neither seek unification with Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG),, is a country in Central Europe. It is the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany lies between the Baltic and North Sea to the north and the Alps to the sou ...

nor attempt to restore the Habsburg dynasty to power. In return, Czechoslovakia promised a substantial loan to the struggling, cash-strapped rump state. The treaty would also generally improve Austria's international standing and make it easier for Austria to secure additional loans from other countries.

The Christian Socials were in favor of the treaty, but their remaining coalition partner, the Greater German People's Party, was vehemently opposed. Ardently pan-German, the People's Party had been hoping that Austria would, sooner or later, defy the Treaty of Saint-Germain and would seek accession to the German Reich

German ''Reich'' (lit. German Realm, German Empire, from german: Deutsches Reich, ) was the constitutional name for the German nation state that existed from 1871 to 1945. The ''Reich'' became understood as deriving its authority and sovereignty ...

. The party had also been hoping that the unification of all Germans would extend to the Sudeten Germans, the German-speaking former Habsburg subjects living in what used to be Bohemia. Schober, whom the party had considered an ally, was renouncing both these goals.

In the final days of December 1921, the People's Party staged protest rallies against the treaty all over the country. On 16 January 1922, it also withdrew its representative from Schober's cabinet.

As long as Schober himself remained in office, however, the People's Party was still bound by the original coalition agreement. The agreement required the party to vote in support of government bills in the National Council, and one of the government bills on the table in January 1922 was the ratification of the Treaty of Lana. On 26 January, hoping to appease the People's Party by releasing it from its contractual obligation, Schober stepped down. Schober's resignation did not elevate Breisky to the chancellorship automatically, but Hainisch instantaneously appointed him caretaker head of government.

The Treaty of Lana was ratified with the votes of Christian Socials and Social Democrats, while the People's Party voted against.

Behind the scenes, Christian Social representatives, and possibly politicians of other parties as well, were lobbying Schober to return; it was widely felt that there simply was no alternative. Schober let himself be persuaded. On 27 January he was elected chancellor a second time. The People's Party did not return its representative to Schober's cabinet but was ready to recommence support for Schober in the National Council. The Breisky government

The Breisky government (german: Regierung Breisky) was a caretaker cabinet in office from midday of January 26 to midday of January 27, 1922. The government came to be when Chancellor Johannes Schober stepped down in order to put a formal end to a ...

had been in office for just about twenty-four hours.

Breisky resumed his roles as vice chancellor and state secretary of education.

Chief statistician

In May 1922, just four months later, Schober was forced to resign again.Ignaz Seipel

Ignaz Seipel (19 July 1876 – 2 August 1932) was an Austrian prelate, Catholic theologian and politician of the Christian Social Party. He was its chairman from 1921 to 1930 and served as Austria's federal chancellor twice, from 1922 to 1924 ...

, Schober's successor, had no use for Breisky in his cabinet. Breisky returned to his old position as the executive department director () in the Chancellery, where he seems to have served Seipel as diligently as he used to serve Renner. Seipel showed himself grateful. On 21 February 1923, Breisky was made the president of the Austrian Statistics Office. Austria's economic situation was still troubled and, in fact, worsening. The administrators in charge of economic policy were hampered by lack of reliable information. It was unclear how many inhabitants the country had, how many of them were employed, how many businesses there were, and how much they produced. The agency Breisky took over was massively understaffed and poorly organized. Breisky, whose appointment was originally ridiculed for his complete lack of any relevant training or experience, proved himself capable and energetic. Breisky turned the Statistics Office around, then took the initiative in creating the Austrian Institute of Economic Research

The Austrian Institute of Economic Research (german: Österreichisches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung, WIFO) is a private non-profit association located in Vienna, Austria.

The institute was founded in 1927 by Friedrich Hayek and Ludwig von ...

( at the time), thus making sure that the agency would be kept on its toes by competition from a think tank of independent scholars.

Later years

Throughout his life, Breisky had been suffering from poor eyesight. Hisfar-sightedness

Far-sightedness, also known as long-sightedness, hypermetropia, or hyperopia, is a condition of the eye where distant objects are seen clearly but near objects appear blurred. This blurred effect is due to incoming light being focused behind, in ...

and astigmatism

Astigmatism is a type of refractive error due to rotational asymmetry in the eye's refractive power. This results in distorted or blurred vision at any distance. Other symptoms can include eyestrain, headaches, and trouble driving at ni ...

had already been bad enough to get him declared permanently unfit for military service in 1894, and they had been worsening since.

On 18 February 1931, Breisky tendered his retirement. His request was granted on 1 October.

Breisky spent his final years in Klosterneuburg

Klosterneuburg (; frequently abbreviated as Kloburg by locals) is a town in Tulln District in the Austrian state of Lower Austria. It has a population of about 27,500. The Klosterneuburg Monastery, which was established in 1114 and soon after giv ...

, where he lived with his wife; he had married Rosa Kowarik, his long-time housekeeper, in 1927. Breisky does not appear to have kept in touch with former colleagues or political collaborators, but he was active in the Pan-Europe Movement and held honorary positions in a number of charities and hobbyists' clubs. He was the honorary president of the Viennese Animal Welfare Association () and an honorary member of the local numismatic

Numismatics is the study or collection of currency, including coins, tokens, paper money, medals and related objects.

Specialists, known as numismatists, are often characterized as students or collectors of coins, but the discipline also includ ...

society. Breisky spent most of his time in his sprawling library, reading with a magnifying glass. He tried to prevent his eye problem from getting worse by self-medicating by consuming massive amounts of carrots and lemon juice.

There is evidence that Breisky felt disheartened by the political developments he witnessed during his sunset days. He expressed no support either for the Austrofascist

The Federal State of Austria ( de-AT, Bundesstaat Österreich; colloquially known as the , "Corporate State") was a continuation of the First Austrian Republic between 1934 and 1938 when it was a one-party state led by the clerical fascist Fa ...

takeover in 1934 or for the Nazi takeover in 1938. He withdrew further from public life after the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

came to power in Austria, resigning even his nominal membership in the International Statistical Institute

The International Statistical Institute (ISI) is a professional association of statisticians. It was founded in 1885, although there had been international statistical congresses since 1853. The institute has about 4,000 elected members from gov ...

.

After the death of his wife on 17 November 1943, Breisky hired a nurse to take care of him.

In September 1944, apparently reported to the authorities by his nurse, he was arrested by the Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one or ...

for listening to the BBC, a so-called .

On 25 September, shortly after his release from Nazi custody, Breisky committed suicide.

Citations

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Breisky, Walter Chancellors of Austria Vice-Chancellors of Austria Christian Social Party (Austria) politicians Austrian people of German Bohemian descent People from Bern 1871 births 1944 deaths Austrian Ministers of Defence Austrian civil servants Austrian jurists Austrian Lutherans 1944 suicides