W. Sterling Cary on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Cary worked in a factory after graduating from Union Theological Seminary because he had been unable to find a position in a Baptist church. He moved to

Cary worked in a factory after graduating from Union Theological Seminary because he had been unable to find a position in a Baptist church. He moved to

Cary was elected committee chairman of a permanent "National Committee for Racial Justice Now" authorized by the United Church of Christ in 1965. At the annual UCC assembly in 1966, he condemned the

Cary was elected committee chairman of a permanent "National Committee for Racial Justice Now" authorized by the United Church of Christ in 1965. At the annual UCC assembly in 1966, he condemned the

At his first NCC governing board meeting, the board voted to direct its member churches to evaluate a study paper on abortion in a move toward advancing Cary's goal of establishing a formal relationship with the

At his first NCC governing board meeting, the board voted to direct its member churches to evaluate a study paper on abortion in a move toward advancing Cary's goal of establishing a formal relationship with the

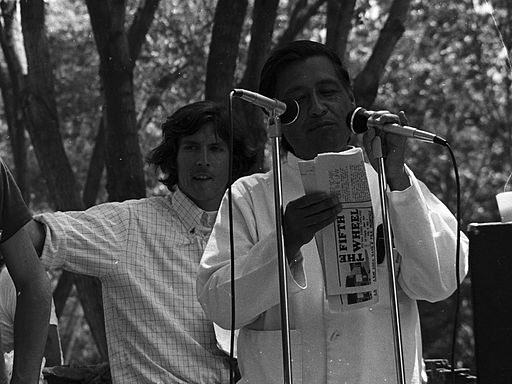

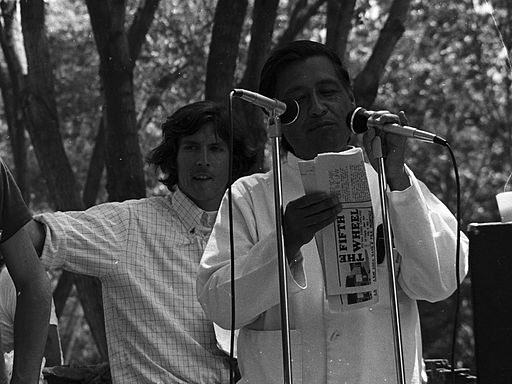

William Sterling Cary (August 10, 1927 – November 14, 2021) was an American Christian minister. From 1972 to 1975, he was the first Black president of the

church.

He graduated from Plainfield High School in 1945. After the dean of the mostly white high school told him that he had lost an election for student body president—an election he believed he had resoundingly won—he decided to enroll in the all-black National Council of Churches

The National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA, usually identified as the National Council of Churches (NCC), is the largest ecumenical body in the United States. NCC is an ecumenical partnership of 38 Christian faith groups in the Uni ...

(NCC) in its history.

Born and raised in Plainfield, New Jersey

Plainfield is a city in Union County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey, known by its nickname as "The Queen City."

, Cary earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1949 from Morehouse College

, mottoeng = And there was light (literal translation of Latin itself translated from Hebrew: "And light was made")

, type = Private historically black men's liberal arts college

, academic_affiliations ...

, where he served as student body president. He was ordained a Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only (believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul compete ...

minister and studied at Union Theological Seminary, receiving a Bachelor of Divinity

In Western universities, a Bachelor of Divinity or Baccalaureate in Divinity (BD or BDiv; la, Baccalaureus Divinitatis) is a postgraduate academic degree awarded for a course taken in the study of divinity or related disciplines, such as theology ...

degree in 1952. Unable to find a position in a Baptist church, he became a pastor at a Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

church from 1952 to 1955 in Youngstown, Ohio

Youngstown is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio, and the largest city and county seat of Mahoning County, Ohio, Mahoning County. At the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, Youngstown had a city population of 60,068. It is a principal city of ...

, and then at an experimental interdenominational church in Brooklyn

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

. Cary changed his denominational affiliation to the United Church of Christ

The United Church of Christ (UCC) is a mainline Protestant Christian denomination based in the United States, with historical and confessional roots in the Congregational, Calvinist, Lutheran, and Anabaptist traditions, and with approximately 4 ...

(UCC) in 1958. He became increasingly active in the Black liberation theology movement in the 1960s, advocating for racial justice and equality within the UCC and on a broader scale.

He was elected administrator of the New York Metropolitan Association of the UCC in 1968, and four years later he was unanimously elected to a three-year term as president of the National Council of Churches. Cary was a harsh critic of U.S. President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

's budget cuts to affordable housing

Affordable housing is housing which is deemed affordable to those with a household income at or below the median as rated by the national government or a local government by a recognized housing affordability index. Most of the literature on affo ...

and anti-poverty measures. Though he disagreed with Nixon's successor, Gerald Ford

Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr. ( ; born Leslie Lynch King Jr.; July 14, 1913December 26, 2006) was an American politician who served as the 38th president of the United States from 1974 to 1977. He was the only president never to have been elected ...

, on issues related to the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

, they rekindled a long-neglected relationship between the NCC and the White House, and Ford later appointed Cary to an advisory committee that oversaw the resettlement of South Asian refugees in the United States. After Cary's presidency ended, he continued in his role as the executive minister of the Illinois conference of the UCC until his retirement in 1994.

Early life and education

Cary was born inPlainfield, New Jersey

Plainfield is a city in Union County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey, known by its nickname as "The Queen City."

, on August 10, 1927. His father, Andrew Jackson Cary, was a real estate broker, and his mother, Sadie Walker, was a homemaker. He had seven siblings. Growing up in Plainfield, he was active in the Boy Scouts of America

The Boy Scouts of America (BSA, colloquially the Boy Scouts) is one of the largest scouting organizations and one of the largest youth organizations in the United States, with about 1.2 million youth participants. The BSA was founded i ...

, and attended Washington School where he was the founding president of the junior high YMCA

YMCA, sometimes regionally called the Y, is a worldwide youth organization based in Geneva, Switzerland, with more than 64 million beneficiaries in 120 countries. It was founded on 6 June 1844 by George Williams in London, originally ...

club and the eighth-grade class president. In 1944, the ''Courier News

The ''Courier News'' is a daily newspaper headquartered in Somerville, New Jersey, that serves Somerset County and other areas of Central Jersey. The paper has been owned by Gannett since 1927.

Notable employees

* John Curley, former pre ...

'' called Cary "the boy preacher" in an announcement of his sermon for Young People's Day at a local AME #REDIRECT AME #REDIRECT AME

{{redirect category shell, {{R from other capitalisation{{R from ambiguous page ...

{{redirect category shell, {{R from other capitalisation{{R from ambiguous page ...Morehouse College

, mottoeng = And there was light (literal translation of Latin itself translated from Hebrew: "And light was made")

, type = Private historically black men's liberal arts college

, academic_affiliations ...

in Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,715 ...

, Georgia. At Morehouse, Cary majored in sociology and occasionally returned to Plainfield to preach at Calvary Baptist Church; by 1947, he was an assistant pastor there. He was a member of the Kappa Alpha Psi

Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity, Inc. () is a historically African American fraternity. Since the fraternity's founding on January 5, 1911 at Indiana University Bloomington, the fraternity has never restricted membership on the basis of color, creed ...

fraternity and was elected student body president in 1948. The same year, he was ordained a Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only (believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul compete ...

minister then graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1949.

Cary continued his studies at Union Theological Seminary in New York City while also serving as a student assistant to the minister of Grace Congregational Church. In 1950, at the end of his first year, he was elected class president for the upcoming year becoming the first Black class president in the seminary's history. He was elected student body president the following year and graduated with a Master of Divinity

For graduate-level theological institutions, the Master of Divinity (MDiv, ''magister divinitatis'' in Latin) is the first professional degree of the pastoral profession in North America. It is the most common academic degree in seminaries and divi ...

degree in 1952.

Career

Early ministry (1952–1964)

Cary worked in a factory after graduating from Union Theological Seminary because he had been unable to find a position in a Baptist church. He moved to

Cary worked in a factory after graduating from Union Theological Seminary because he had been unable to find a position in a Baptist church. He moved to Youngstown, Ohio

Youngstown is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio, and the largest city and county seat of Mahoning County, Ohio, Mahoning County. At the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, Youngstown had a city population of 60,068. It is a principal city of ...

, to become the pastor of Butler Memorial Presbyterian Church from 1952 to 1955. During that time, he co-chaired the United Negro College Fund

UNCF, the United Negro College Fund, also known as the United Fund, is an American philanthropic organization that funds scholarships for black students and general scholarship funds for 37 private historically black colleges and universities. ...

in Youngstown and was active in other local organizations and committees including the YMCA and the Mahoning County

Mahoning County is a county in the U.S. state of Ohio. As of the 2020 census, the population was 228,614. Its county seat and largest city is Youngstown. The county is named for a Lenape word meaning "at the licks" or "there is a lick", refer ...

Mental Health Council. He married Marie Belle Phillips, a teacher in the SoHo

Soho is an area of the City of Westminster, part of the West End of London. Originally a fashionable district for the aristocracy, it has been one of the main entertainment districts in the capital since the 19th century.

The area was develop ...

school system, on July 11, 1953. They were married in Carron Street Baptist Church in Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Wester ...

, Pennsylvania, and later had four children: Yvonne, Denise, Patricia, and W. Sterling Jr. In December 1955, Cary was assigned to be the pastor at an interdenominational and interracial church in Brooklyn

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

that included the Baptist, Congregational Christian, Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's b ...

, Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

, and Reformed

Reform is beneficial change

Reform may also refer to:

Media

* ''Reform'' (album), a 2011 album by Jane Zhang

* Reform (band), a Swedish jazz fusion group

* ''Reform'' (magazine), a Christian magazine

*''Reforme'' ("Reforms"), initial name of the ...

denominations. It was the first interdenominational church built in a public housing project in the United States. He began his position at the church, named the Church of the Open Door, on January 1, 1956.

In July 1958, Cary was named the pastor at Grace Congregational Church where he was previously a student assistant to the minister during his seminary studies. He changed his denominational affiliation from Baptist to the United Church of Christ

The United Church of Christ (UCC) is a mainline Protestant Christian denomination based in the United States, with historical and confessional roots in the Congregational, Calvinist, Lutheran, and Anabaptist traditions, and with approximately 4 ...

(UCC) and began his new position on September 1, 1958, succeeding Herbert King who had resigned to become a professor at McCormick Theological Seminary

McCormick Theological Seminary is a private Presbyterian seminary in Chicago, Illinois. It shares a campus with the Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago, bordering the campus of the University of Chicago. A letter of intent was signed on May 5 ...

. Cary participated in several discussions on juvenile delinquency

Juvenile delinquency, also known as juvenile offending, is the act of participating in unlawful behavior as a minor or individual younger than the statutory age of majority. In the United States of America, a juvenile delinquent is a person ...

including a televised panel discussion on NBC

The National Broadcasting Company (NBC) is an Television in the United States, American English-language Commercial broadcasting, commercial television network, broadcast television and radio network. The flagship property of the NBC Enterta ...

's "Frontiers of Faith" series in 1961. He was a speaker at a 1963 rally between the New York NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E.&nb ...

and Governor Nelson Rockefeller

Nelson Aldrich Rockefeller (July 8, 1908 – January 26, 1979), sometimes referred to by his nickname Rocky, was an American businessman and politician who served as the 41st vice president of the United States from 1974 to 1977. A member of t ...

and frequently spoke on racial issues in the 1960s. After the Harlem riot of 1964

The Harlem riot of 1964 occurred between July 16 and 22, 1964. It began after James Powell, a 15-year-old African American, was shot and killed by police Lieutenant Thomas Gilligan in front of Powell's friends and about a dozen other witnesses. ...

, while not condoning the rioting, he called for the suspension of the shooter, Lieutenant Thomas Gilligan, and the establishment of a civilian board to examine allegations of police brutality.

Towards Black liberation theology (1965–1971)

Cary was elected committee chairman of a permanent "National Committee for Racial Justice Now" authorized by the United Church of Christ in 1965. At the annual UCC assembly in 1966, he condemned the

Cary was elected committee chairman of a permanent "National Committee for Racial Justice Now" authorized by the United Church of Christ in 1965. At the annual UCC assembly in 1966, he condemned the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

and other "insane bigoted mobs", and forcefully called for high-quality integrated schools and fairer employment laws. He was named executive coordinator of the committee in March 1966; at that time, he was also the vice president of the Manhattan division of the Protestant Council of the City of New York and a member of the Mayor of New York's youth task force. Cary advocated for racial justice both within the UCC, calling for increased funding to build new churches in Black communities, and on a broader scale by helping to establish the "National Committee of Negro Churchmen" which promoted the Black Power movement. The organization purchased a full-page ad in ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' demanding changes to segregated schools and discriminatory laws.

At the Vermont Conference of the UCC in September 1966, Cary continued to advocate for the Black Power movement and Black liberation theology stating that "equality will come not by goodwill or love, but by the Negro's achieving independence, strength and some measure of wealth." After his lectures, the conference ministers voted to adopt several race-related resolutions, including lobbying the state government for open housing

Housing discrimination in the United States refers to the historical and current barriers, policies, and biases that prevent equitable access to housing. Housing discrimination became more pronounced after the abolition of slavery in 1865, typical ...

and encouraging churches to appoint more Black pastors. In his role as chairman of the National Committee for Racial Justice Now, Cary also called on the UCC to protect ministers who spoke out on racial issues and other controversial topics such as the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

while also criticizing the firing of some outspoken ministers.

In June 1968, he was elected administrator of the New York Metropolitan Association of the United Church of Christ, a position in which he oversaw 77 churches in the district comprising approximately 36,000 UCC members. He was the first Black minister to hold the position. He was a signer of the 1969 Black Manifesto

The Black Manifesto was a 1969 manifesto that demanded $500 million (~$ in ) in reparations from white churches and synagogues for their participation in the injustices of slavery and segregation committed against African-Americans.

History

The ...

that called for white churches and synagogues to pay hundreds of millions of dollars in reparations

Reparation(s) may refer to:

Christianity

* Restitution (theology), the Christian doctrine calling for reparation

* Acts of reparation, prayers for repairing the damages of sin

History

*War reparations

**World War I reparations, made from G ...

. Cary opposed a 1971 effort to reorganize Protestant and Orthodox denominations into a tiered system with increased separation between individual denominations.

National Council of Churches (1972–1975)

The ''Minneapolis Star

The ''Star Tribune'' is the largest newspaper in Minnesota. It originated as the ''Minneapolis Tribune'' in 1867 and the competing ''Minneapolis Daily Star'' in 1920. During the 1930s and 1940s, Minneapolis's competing newspapers were consolida ...

'' reported in September 1972 that Cary would be put forth by a nominating committee for president of the National Council of Churches

The National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA, usually identified as the National Council of Churches (NCC), is the largest ecumenical body in the United States. NCC is an ecumenical partnership of 38 Christian faith groups in the Uni ...

, the largest ecumenical body in the United States, and that he was expected to be elected. Running unopposed, he was unanimously elected to a three-year term at the NCC's general assembly in Dallas

Dallas () is the List of municipalities in Texas, third largest city in Texas and the largest city in the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, the List of metropolitan statistical areas, fourth-largest metropolitan area in the United States at 7.5 ...

, Texas, on December 7, 1972. Cary succeeded Cynthia Clark Wedel, was the first Black president of the NCC, and its youngest president at the time. Upon his election, he pledged to focus on integrating churches, uniting different denominations, and advocating for affordable housing and education. At the Dallas meeting, the NCC general assembly also voted to establish a new, more diverse governing body to be rolled out during Cary's first year in office. In February 1973, Cary joined other religious leaders, including Paul Moore Jr.

Paul Moore Jr. (November 15, 1919 – May 1, 2003) was a bishop of the Episcopal Church in the United States of America, Episcopal Church and former United States Marine Corps officer. He served as the 13th Episcopal Diocese of New York, Bishop o ...

and Balfour Brickner, in criticizing President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

's proposed budget which decreased funding for affordable housing and other anti-poverty measures. He accused Nixon of "declar ngwar on the poor people and members of this country's minorities" and called on Congress to reject the budget. After Nixon fired Archibald Cox

Archibald Cox Jr. (May 17, 1912 – May 29, 2004) was an American lawyer and law professor who served as U.S. Solicitor General under President John F. Kennedy and as a special prosecutor during the Watergate scandal. During his career, he was a p ...

during the Watergate scandal

The Watergate scandal was a major political scandal in the United States involving the administration of President Richard Nixon from 1972 to 1974 that led to Nixon's resignation. The scandal stemmed from the Nixon administration's continual ...

, Cary released a statement urging Congress to "examine the President's fitness to remain in office".

At his first NCC governing board meeting, the board voted to direct its member churches to evaluate a study paper on abortion in a move toward advancing Cary's goal of establishing a formal relationship with the

At his first NCC governing board meeting, the board voted to direct its member churches to evaluate a study paper on abortion in a move toward advancing Cary's goal of establishing a formal relationship with the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

. In May 1973, he received an honorary Doctor of Laws

A Doctor of Law is a degree in law. The application of the term varies from country to country and includes degrees such as the Doctor of Juridical Science (J.S.D. or S.J.D), Juris Doctor (J.D.), Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.), and Legum Doctor (LL. ...

degree from Bishop College

Bishop College was a historically black college, founded in Marshall, Texas, United States, in 1881 by the Baptist Home Mission Society. It was intended to serve students in east Texas, where the majority of the black population lived at the t ...

in Dallas for "unique Christian humanism predicated upon justice for all". That same month, Cary and NCC General Secretary R. H. Edwin Espy apologized for and retracted a statement they had sent to the House Committee on Ways and Means

The Committee on Ways and Means is the chief tax-writing committee of the United States House of Representatives. The committee has jurisdiction over all taxation, tariffs, and other revenue-raising measures, as well as a number of other program ...

opposing tax credit

A tax credit is a tax incentive which allows certain taxpayers to subtract the amount of the credit they have accrued from the total they owe the state. It may also be a credit granted in recognition of taxes already paid or a form of state "disc ...

s for students attending private schools, after they had received backlash from Catholic bishops. Cary was a vocal supporter of the United Farm Workers

The United Farm Workers of America, or more commonly just United Farm Workers (UFW), is a labor union for farmworkers in the United States. It originated from the merger of two workers' rights organizations, the Agricultural Workers Organizing ...

' grape strike led by Cesar Chavez

Cesar Chavez (born Cesario Estrada Chavez ; ; March 31, 1927 – April 23, 1993) was an American labor leader and civil rights activist. Along with Dolores Huerta, he co-founded the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA), which later merged ...

. In 1974, he advocated for amnesty for draft evaders in the Vietnam War. He later praised President Gerald Ford

Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr. ( ; born Leslie Lynch King Jr.; July 14, 1913December 26, 2006) was an American politician who served as the 38th president of the United States from 1974 to 1977. He was the only president never to have been elected ...

's call for conditional amnesty while urging the president to make it unconditional. Cary moved to Chicago, Illinois, after he was elected executive minister of the Illinois Conference of the United Church of Christ in September 1974. This made him the first Black executive minister in the conference's history. In February 1975, Cary and other religious leaders met with Ford; it was the first time in a decade that church leaders were invited to the White House. The meeting re-established the relationship between the NCC and the White House, though Ford and church leaders continued to disagree on issues like amnesty and Vietnam aid.

In the aftermath of the Vietnam War, he was appointed by President Ford to a 17-member advisory committee to oversee the resettlement of Southeast Asian refugees. In March 1975, the NCC voted for the first time to support gay rights passing a resolution that condemned discrimination on the basis of "affectional or sexual preference". At the same meeting, the governing board voted in support of the Equal Rights Amendment

The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) is a proposed amendment to the United States Constitution designed to guarantee equal legal rights for all American citizens regardless of sex. Proponents assert it would end legal distinctions between men and ...

and resolved to investigate Cary's claim that the Nixon administration had bugged NCC phones in order to conduct special tax audits of the organization. He sharply criticized Operation Babylift

Operation or Operations may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* ''Operation'' (game), a battery-operated board game that challenges dexterity

* Operation (music), a term used in musical set theory

* ''Operations'' (magazine), Multi-Ma ...

, in which children were mass-evacuated from South Vietnam

South Vietnam, officially the Republic of Vietnam ( vi, Việt Nam Cộng hòa), was a state in Southeast Asia that existed from 1955 to 1975, the period when the southern portion of Vietnam was a member of the Western Bloc during part of th ...

to the United States, accusing the U.S. government of staging the operation for political gain and saying that the Vietnamese people described it an "insensitive kidnap operation". ''Ebony

Ebony is a dense black/brown hardwood, coming from several species in the genus ''Diospyros'', which also contains the persimmons. Unlike most woods, ebony is dense enough to sink in water. It is finely textured and has a mirror finish when pol ...

'' named Cary among the 100 most influential Black Americans in both 1974 and 1975. Cary's three-year term as NCC president ended on October 11, 1975, when the governing board elected William Phelps Thompson who was the chief executive of the United Presbyterian Church at the time.

Post-presidential ministry (1976–1994)

After his presidency, Cary continued in his role as the Illinois conference minister and continued his calls for Black churches to combat racial injustice. In 1981, he was elected chair of the Council of Conference Executives of the UCC. Cary was one of six finalists considered by a nominating committee for UCC president in 1989, though he was not ultimately selected as the nominee. He retired in 1994 after two decades as the Illinois conference minister.Death

After a long illness, Cary died of heart failure in his home inFlossmoor, Illinois

Flossmoor () is a village in Cook County, Illinois, United States. The population was 9,704 at the 2020 census. Flossmoor is approximately 25 miles south of the Chicago Loop.

Geography

Flossmoor is located at (41.541684, -87.684970).

According ...

, on November 14, 2021. He was 94 years old. He was survived by his wife of 68 years, Marie Belle, four children, two grandchildren, and three great-grandchildren.

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Cary, W. Sterling 1927 births 2021 deaths 20th-century Baptist ministers from the United States Activists for African-American civil rights Activists from New Jersey African-American Baptist ministers Christian clergy from New Jersey Morehouse College alumni People from Plainfield, New Jersey Plainfield High School (New Jersey) alumni Union Theological Seminary (New York City) alumni United Church of Christ ministers