W. G. Hardy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

William George Hardy (February 3, 1895 – August 28, 1979) was a Canadian

Hardy obtained

Hardy obtained

Hardy received his professorship in 1922, then served as head of the Department of Classics at the University of Alberta from 1938 to 1964. He used the airwaves to educate about the Classics and world events, and gave 250 radio talks on

Hardy received his professorship in 1922, then served as head of the Department of Classics at the University of Alberta from 1938 to 1964. He used the airwaves to educate about the Classics and world events, and gave 250 radio talks on

Hardy was elected second vice-president of the

Hardy was elected second vice-president of the

Hardy was elected first vice-president of the CAHA on May 6, 1936.''Canadian Amateur Hockey Association (1990)''. p. 127 He was delegated to assist Fry in conducting a mail-in vote on the CAHA proposals, and to draft a letter to send to AAU of C delegates. Fry published a letter to the CAHA in his ''

Hardy was elected first vice-president of the CAHA on May 6, 1936.''Canadian Amateur Hockey Association (1990)''. p. 127 He was delegated to assist Fry in conducting a mail-in vote on the CAHA proposals, and to draft a letter to send to AAU of C delegates. Fry published a letter to the CAHA in his ''

Hardy was re-elected president of the CAHA on April 12, 1939. He continued the affiliation with AHAUS, in objection to the protest by the Amateur Athletic Union of the United States. He received a letter from LIHG president

Hardy was re-elected president of the CAHA on April 12, 1939. He continued the affiliation with AHAUS, in objection to the protest by the Amateur Athletic Union of the United States. He received a letter from LIHG president

In April 1943,

In April 1943,

Hardy felt the CAHA had a tough decision ahead as to whether it could form strong enough teams for international competition that held true to the

Hardy felt the CAHA had a tough decision ahead as to whether it could form strong enough teams for international competition that held true to the

The LIHG was renamed the

The LIHG was renamed the

Hardy remained involved with the AAHA, being elected to its board of directors as a representatives from the northern zone Alberta. He also represented the AAHA at the national CAHA meetings until 1953. He served as a convenor on the Western Canada intermediate hockey committee, and awarded the

Hardy remained involved with the AAHA, being elected to its board of directors as a representatives from the northern zone Alberta. He also represented the AAHA at the national CAHA meetings until 1953. He served as a convenor on the Western Canada intermediate hockey committee, and awarded the

Hardy stated that writing was his hobby, but he would not depend on it for income. He was inspired to write due to his love of the classics, and said stories are everywhere, "all you have to do is look for them". He later said, he said he was a fast writer and committed to producing 70 pages each week. He felt

Hardy stated that writing was his hobby, but he would not depend on it for income. He was inspired to write due to his love of the classics, and said stories are everywhere, "all you have to do is look for them". He later said, he said he was a fast writer and committed to producing 70 pages each week. He felt

Hardy's first novel ''Son of Eli'' was purchased by ''Maclean's'' for $2,500, and published as a series from 1928 to 1929. The novel tells the story of Ontario farm and city life. His second novel, ''Father Abraham'' (1935), was published simultaneously in London, New York and Toronto by

Hardy's first novel ''Son of Eli'' was purchased by ''Maclean's'' for $2,500, and published as a series from 1928 to 1929. The novel tells the story of Ontario farm and city life. His second novel, ''Father Abraham'' (1935), was published simultaneously in London, New York and Toronto by

Hardy played baseball and basketball for seven years after he joined the faculty of University of Alberta, but most of his spare time was consumed by writing. He financed trips around the world from sales of his books, and travelled regularly to the Mediterranean region with his wife. He spoke fluent French in addition to Greek and Latin, and was president of the Edmonton Little Theatre in 1935.

His wife Llewella died on December 15, 1958, due to a stroke at age 61. They had been married for 39 years, and had three children. He dedicated his book ''From Sea Unto Sea'', to the memory of his wife in 1959.

Hardy was the guest speaker at the opening banquet for the Edmonton Sports Hall of Fame in March 1961. He remarked that the nominees "conformed to the Greek ideal of the all-round man, both in education and in sport".

Hardy stated in a 1965 interview that Canada had earned the right to host the 1967 Ice Hockey World Championships during the Canadian Centennial, and the IIHF "made a serious mistake" in awarding hosting duties to Austria instead. He felt that Canada "must completely reassess the terms of its participating in a world event which it did the most to make". In 1970, he supported the decision by CAHA president

Hardy played baseball and basketball for seven years after he joined the faculty of University of Alberta, but most of his spare time was consumed by writing. He financed trips around the world from sales of his books, and travelled regularly to the Mediterranean region with his wife. He spoke fluent French in addition to Greek and Latin, and was president of the Edmonton Little Theatre in 1935.

His wife Llewella died on December 15, 1958, due to a stroke at age 61. They had been married for 39 years, and had three children. He dedicated his book ''From Sea Unto Sea'', to the memory of his wife in 1959.

Hardy was the guest speaker at the opening banquet for the Edmonton Sports Hall of Fame in March 1961. He remarked that the nominees "conformed to the Greek ideal of the all-round man, both in education and in sport".

Hardy stated in a 1965 interview that Canada had earned the right to host the 1967 Ice Hockey World Championships during the Canadian Centennial, and the IIHF "made a serious mistake" in awarding hosting duties to Austria instead. He felt that Canada "must completely reassess the terms of its participating in a world event which it did the most to make". In 1970, he supported the decision by CAHA president

Hardy received several merit awards from hockey associations. He was made a life member of the CAHA on April 14, 1941, and was made a life member of the AAHA on November 10, 1941. He was given the AHAUS citation award in 1950, the Ontario Hockey Association Gold Stick award in 1953, and the CAHA order of merit in 1969. The CAHA presented Hardy with a service medallion at its general meeting in 1969.

For his literary career, he was named a lifetime fellow in the International Association of

Hardy received several merit awards from hockey associations. He was made a life member of the CAHA on April 14, 1941, and was made a life member of the AAHA on November 10, 1941. He was given the AHAUS citation award in 1950, the Ontario Hockey Association Gold Stick award in 1953, and the CAHA order of merit in 1969. The CAHA presented Hardy with a service medallion at its general meeting in 1969.

For his literary career, he was named a lifetime fellow in the International Association of

professor

Professor (commonly abbreviated as Prof.) is an Academy, academic rank at university, universities and other post-secondary education and research institutions in most countries. Literally, ''professor'' derives from Latin as a "person who pr ...

, writer, and ice hockey

Ice hockey (or simply hockey) is a team sport played on ice skates, usually on an ice skating rink with lines and markings specific to the sport. It belongs to a family of sports called hockey. In ice hockey, two opposing teams use ice hock ...

administrator. He lectured on the Classics

Classics or classical studies is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, classics traditionally refers to the study of Classical Greek and Roman literature and their related original languages, Ancient Greek and Latin. Classics ...

at the University of Alberta

The University of Alberta, also known as U of A or UAlberta, is a public research university located in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. It was founded in 1908 by Alexander Cameron Rutherford,"A Gentleman of Strathcona – Alexander Cameron Rutherfor ...

from 1922 to 1964, and served as president of the Canadian Authors Association

The Canadian Authors Association is Canada's oldest association for writers and authors. The organization has published several periodicals, organized local chapters and events for Canadian writers, and sponsors writing awards, including the Gover ...

. He was an administrator of Canadian and international ice hockey, and served as president of the Alberta Amateur Hockey Association

Alberta ( ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is part of Western Canada and is one of the three prairie provinces. Alberta is bordered by British Columbia to the west, Saskatchewan to the east, the Northwest Territ ...

, the Canadian Amateur Hockey Association

The Canadian Amateur Hockey Association (CAHA; french: Association canadienne de hockey amateur) was the national governing body of amateur ice hockey in Canada from 1914 until 1994, when it merged with Hockey Canada. Its jurisdiction include ...

(CAHA), the International Ice Hockey Association

The International Ice Hockey Association was a governing body for international ice hockey. It was established in 1940 when the Canadian Amateur Hockey Association wanted more control over international hockey, and was in disagreement with the ...

, and the International Ice Hockey Federation

The International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF; french: Fédération internationale de hockey sur glace; german: Internationale Eishockey-Föderation) is a worldwide governing body for ice hockey. It is based in Zurich, Switzerland, and has 83 m ...

.

Hardy was self-taught in Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

and Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

. He paid his way through university by earning scholarships, and won the Governor General's Academic Medal

The Governor General's Academic Medal is awarded to the student graduating with the highest grade point average from a Canadian high school, college or university program. They are presented by the educational institution on behalf of the Governor ...

in Classics and English. He earned a Master of Arts

A Master of Arts ( la, Magister Artium or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA, M.A., AM, or A.M.) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Tho ...

at the University of Toronto

The University of Toronto (UToronto or U of T) is a public research university in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, located on the grounds that surround Queen's Park. It was founded by royal charter in 1827 as King's College, the first institution ...

, and then a Ph.D.

A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD, Ph.D., or DPhil; Latin: or ') is the most common degree at the highest academic level awarded following a course of study. PhDs are awarded for programs across the whole breadth of academic fields. Because it is ...

at the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chicago is consistently ranked among the b ...

. He educated about the Classics and world events by radio, and gave 250 talks on CBC Radio

CBC Radio is the English-language radio operations of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. The CBC operates a number of radio networks serving different audiences and programming niches, all of which (regardless of language) are outlined below ...

. He was critical of progressive education

Progressive education, or protractivism, is a pedagogical movement that began in the late 19th century and has persisted in various forms to the present. In Europe, progressive education took the form of the New Education Movement. The term ''pro ...

in Alberta, arguing it did not prepare students for university and lacked emphasis on the three Rs

The three Rs (as in the letter ''R'') are three basic skills taught in schools: reading, writing and arithmetic (usually said as "reading, 'riting, and 'rithmetic"). The phrase appears to have been coined at the beginning of the 19th century.

Th ...

. He authored eight novels, six other books, and over 200 short stories published in ''Maclean's

''Maclean's'', founded in 1905, is a Canadian news magazine reporting on Canadian issues such as politics, pop culture, and current events. Its founder, publisher John Bayne Maclean, established the magazine to provide a uniquely Canadian perspe ...

'' and ''The Saturday Evening Post

''The Saturday Evening Post'' is an American magazine, currently published six times a year. It was issued weekly under this title from 1897 until 1963, then every two weeks until 1969. From the 1920s to the 1960s, it was one of the most widely c ...

''. His books told the history of Canada and the Greco-Roman world

The Greco-Roman civilization (; also Greco-Roman culture; spelled Graeco-Roman in the Commonwealth), as understood by modern scholars and writers, includes the geographical regions and countries that culturally—and so historically—were di ...

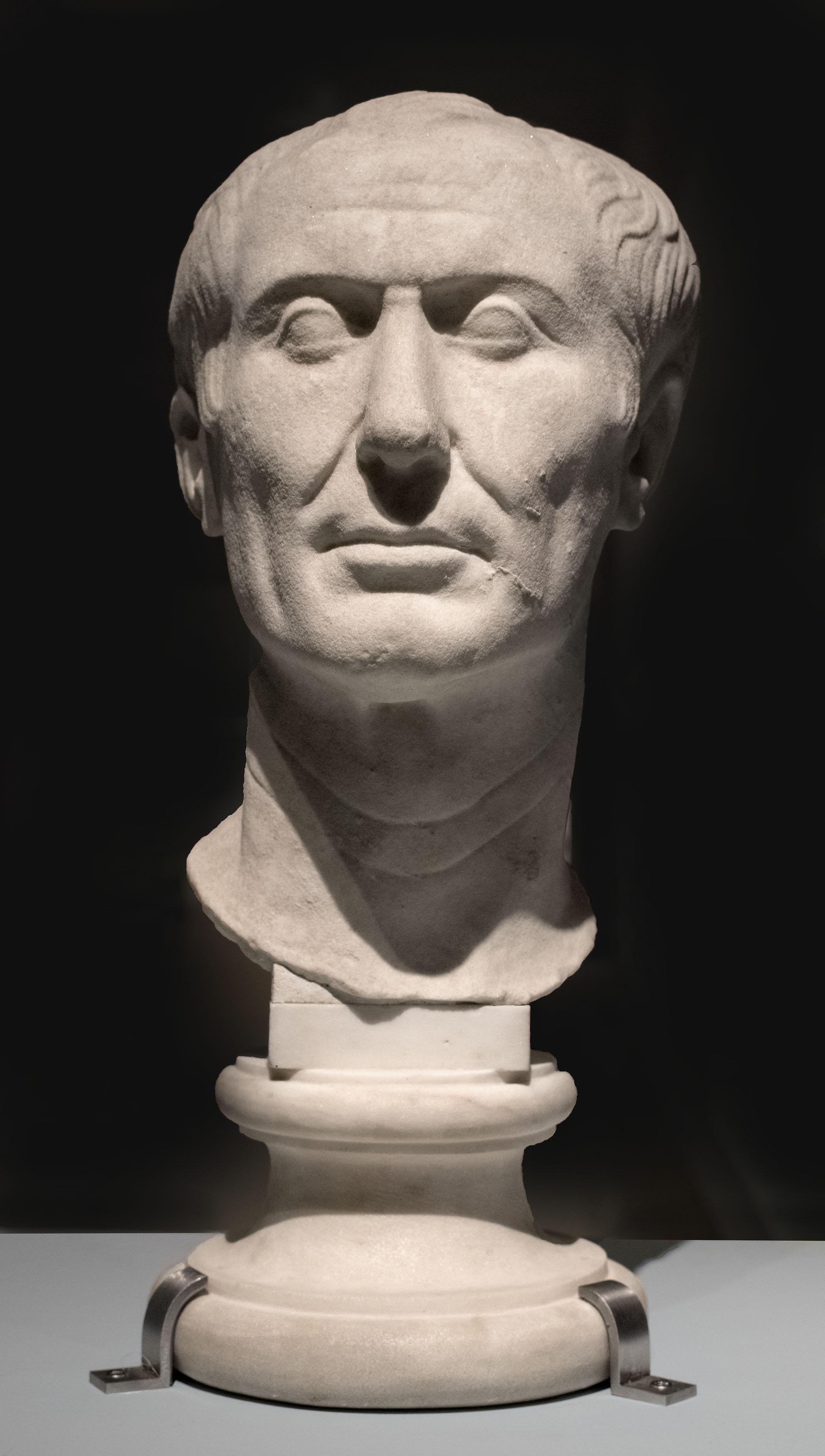

, and his novels included the fictionalized life and times of Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and ...

and Ancient Rome

In modern historiography, ancient Rome refers to Roman civilisation from the founding of the city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. It encompasses the Roman Kingdom (753–509 B ...

. He wrote four plays produced by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation

The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (french: Société Radio-Canada), branded as CBC/Radio-Canada, is a Canadian public broadcaster for both radio and television. It is a federal Crown corporation that receives funding from the government. ...

, was a judge in literary contests, and taught at creative writing workshops.

Hardy coached the Alberta Golden Bears

The Alberta Golden Bears and Pandas are the sports teams that represent the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. Alberta athletics teams have won a total of 93 national championships, including 79 U Sports sanctioned sports, making ...

men's ice hockey team, then became president of the Alberta Amateur Hockey Association and established a new playoffs system for senior ice hockey

Senior hockey refers to amateur or semi-professional ice hockey competition. There are no age restrictions for Senior players, who typically consist of those whose Junior eligibility has expired.

Senior hockey leagues operate under the jurisdict ...

in Western Canada. He was elected to the CAHA executive in 1934, then became its president in 1938. Hardy and George Dudley

George Samuel Dudley (April 19, 1894 – May 8, 1960) was a Canadian ice hockey administrator. He joined the Ontario Hockey Association (OHA) executive in 1928, served as its president from 1934 to 1936, and as its treasurer from 1936 to 1960 ...

recommended updates to the definition of an amateur ice hockey player in 1936, to reflect the financial challenges during the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

to have national playoffs and send the Canada men's national ice hockey team

The Canada men's national ice hockey team (popularly known as Team Canada; french: Équipe Canada) is the ice hockey team representing Canada inter ...

to the Ice Hockey World Championships

The Ice Hockey World Championships are an annual international men's ice hockey tournament organized by the International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF). First officially held at the 1920 Summer Olympics, it is the sport's highest profile annua ...

or ice hockey at the Olympic Games

Ice hockey tournaments have been staged at the Olympic Games since 1920. The men's tournament was introduced at the 1920 Summer Olympics and was transferred permanently to the Winter Olympic Games program in 1924, in France. The women's tournam ...

. Hardy campaigned to the Canadian public who accepted the changes, despite opposition by the Amateur Athletic Union of Canada The history of Canadian sports falls into five stages of development: early recreational activities before 1840; the start of organized competition, 1840–1880; the emergence of national organizations, 1882–1914; the rapid growth of both amateur ...

. As president of the CAHA, he revised playoffs formats for the Allan Cup

The Allan Cup is the trophy awarded annually to the national senior amateur men's ice hockey champions of Canada. It was donated by Sir Montagu Allan of Ravenscrag, Montreal, and has been competed for since 1909. The current champions are the ...

and Memorial Cup

The Memorial Cup () is the national championship of the Canadian Hockey League, a consortium of three major junior ice hockey leagues operating in Canada and parts of the United States. It is a four-team round-robin tournament played between t ...

to become more profitable, and reinvested the money into minor ice hockey

Minor hockey is an umbrella term for amateur ice hockey which is played below the junior age level. Players are classified by age, with each age group playing in its own league. The rules, especially as it relates to body contact, vary from cla ...

in Canada. He negotiated an affiliation agreement with the Amateur Hockey Association of the United States

USA Hockey is the national ice hockey organization in the United States. It is recognized by the International Olympic Committee and the United States Olympic & Paralympic Committee as the governing body for organized ice hockey in the United S ...

in 1938, which led to the formation of the International Ice Hockey Association in 1940, to oversee hockey in North America and Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

. He improved professional–amateur relations with the National Hockey League

The National Hockey League (NHL; french: Ligue nationale de hockey—LNH, ) is a professional ice hockey league in North America comprising 32 teams—25 in the United States and 7 in Canada. It is considered to be the top ranked professional ...

, and negotiated to reimburse the amateur associations for developing professional players. Hardy founded the Western Canada Senior Hockey League The Western Canada Senior Hockey League was a senior ice hockey league that played six seasons in Alberta and Saskatchewan, from 1945 to 1951. The league produced the 1946 Allan Cup and the 1948 Allan Cup champions, and merged into the Pacific Coas ...

in 1945, which later merged with the Pacific Coast Hockey League

The Pacific Coast Hockey League was an ice hockey minor league with teams in the western United States and western Canada that existed in several incarnations: from 1928 to 1931, from 1936 to 1941, and from 1944 to 1952.

PCHL 1928–1931

The firs ...

. He agreed to a merger of the International Ice Hockey Association with the Ligue Internationale de Hockey sur Glace in 1947, which was renamed to the International Ice Hockey Federation

The International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF; french: Fédération internationale de hockey sur glace; german: Internationale Eishockey-Föderation) is a worldwide governing body for ice hockey. It is based in Zurich, Switzerland, and has 83 m ...

in 1948. He was the first North American to be elected its president, and sought for the International Olympic Committee

The International Olympic Committee (IOC; french: link=no, Comité international olympique, ''CIO'') is a non-governmental sports organisation based in Lausanne, Switzerland. It is constituted in the form of an association under the Swiss ...

to recognize the Canadian definition of amateur, and for inclusion of the Soviet Union national ice hockey team

The Soviet national ice hockey team was the national men's ice hockey team of the Soviet Union. From 1954, the team won at least one medal each year at either the Ice Hockey World Championships ...

at the Winter Olympic Games

The Winter Olympic Games (french: link=no, Jeux olympiques d'hiver) is a major international multi-sport event held once every four years for sports practiced on snow and ice. The first Winter Olympic Games, the 1924 Winter Olympics, were he ...

.

Hardy was invested as a Member of the Order of Canada

The Order of Canada (french: Ordre du Canada; abbreviated as OC) is a Canadian state order and the second-highest honour for merit in the system of orders, decorations, and medals of Canada, after the Order of Merit.

To coincide with the ...

in 1974 for contributions to education, literature and amateur sports in Canada. He was posthumously inducted into the Alberta Sports Hall of Fame

The Alberta Sports Hall of Fame is a hall of fame and museum in Red Deer, Alberta, Canada, dedicated to the preservation and history of sports within the province. It was created in 1957 by the Alberta Amateur Athletic Union (AAAU). The museum ...

in 1989, and is the namesake of the Dr. W. G. Hardy Trophy for university hockey, and the Hardy Cup for senior hockey.

Early life and family

William George Hardy was born on February 3, 1895, on the family farm in Peniel, Ontario, to parents George William Hardy and Anne Hardy (née White).''William H. New, ed. (2002),'' p. 474 His parents were ofEnglish

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

ancestry, and owned a plot in Mariposa Township at intersection of Ontario Highway 46

King's Highway 46, commonly referred to as Highway 46, was a provincially maintained highway in the Canadian province of Ontario that connected Highway 7 with Highway 48 in Victoria County. The route existed between 1937 and 1997, a ...

and Peniel Road. He grew up as one of seven children, and completed public school

Public school may refer to:

* State school (known as a public school in many countries), a no-fee school, publicly funded and operated by the government

* Public school (United Kingdom), certain elite fee-charging independent schools in England an ...

at age 10. Hardy stated, "they just let me go at my own speed". He wrote epic poetry by age 12, and taught himself Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

after he had learned Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

. He later attended continuation school in Cannington, Ontario

Cannington is a community in Brock Township, Durham Region, Ontario, Canada. The town is on the Beaver River.

History

Originally part of the original Brock Township, (historic map) Cannington was first settled in 1833. It was first known as Mc ...

, and then Lindsay Collegiate and Vocational Institute

Lindsay Collegiate and Vocational Institute, commonly referred to as LCVI or LC is a secondary school in Lindsay, Ontario.

It is a part of the Trillium Lakelands District School Board. It was previously in the Victoria County Board of Educatio ...

until 1913.

Education and military service

Hardy obtained

Hardy obtained normal school

A normal school or normal college is an institution created to Teacher education, train teachers by educating them in the norms of pedagogy and curriculum. In the 19th century in the United States, instruction in normal schools was at the high s ...

entrance for teaching, then enrolled in Victoria College at the University of Toronto

The University of Toronto (UToronto or U of T) is a public research university in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, located on the grounds that surround Queen's Park. It was founded by royal charter in 1827 as King's College, the first institution ...

to study mathematics. He switched his studies to the Classics

Classics or classical studies is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, classics traditionally refers to the study of Classical Greek and Roman literature and their related original languages, Ancient Greek and Latin. Classics ...

to get a scholarship. In June 1914, he was given a scholarship for passing first year examinations in Classics with honours. He paid his way through university by earning scholarships, and won the Governor General's Academic Medal

The Governor General's Academic Medal is awarded to the student graduating with the highest grade point average from a Canadian high school, college or university program. They are presented by the educational institution on behalf of the Governor ...

in Classics and English. He graduated from the University of Toronto with a Bachelor of Arts

Bachelor of arts (BA or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts degree course is generally completed in three or four years ...

in 1917. He resided at Burwash Hall

Burwash Hall refers to both Burwash Dining Hall and Burwash Hall proper, the second oldest of the residence buildings at Victoria University in Toronto, Canada. Construction began in 1911 and was completed in 1913. It was named after Nathanael Bu ...

during his undergraduate years, and described himself as an excellent athlete who won college medals in hockey, soccer and tennis.

Hardy enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force

The Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) was the expeditionary field force of Canada during the First World War. It was formed following Britain’s declaration of war on Germany on 15 August 1914, with an initial strength of one infantry division ...

on April 30, 1917, during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. He had previously served two years as a Private

Private or privates may refer to:

Music

* " In Private", by Dusty Springfield from the 1990 album ''Reputation''

* Private (band), a Denmark-based band

* "Private" (Ryōko Hirosue song), from the 1999 album ''Private'', written and also recorde ...

in the Canadian Officers' Training Corps The Canadian Officers' Training Corps (COTC) was, from 1912 to 1968, Canada's university officer training programme, fashioned after the University Officers' Training Corps (UOTC) in the United Kingdom. In World War Two the Canadian Army was able ...

, but was rejected to serve in the 109th Battalion due to a heart condition. He subsequently became a Sergeant

Sergeant (abbreviated to Sgt. and capitalized when used as a named person's title) is a rank in many uniformed organizations, principally military and policing forces. The alternative spelling, ''serjeant'', is used in The Rifles and other uni ...

in the University of Toronto Officer's Company. He was given a medical discharge prior to active service. In a 1979 interview, Hardy stated the preexisting heart condition arose from a college track and field meet.

Hardy was a class lecturer at the University of Toronto from 1918 to 1920. He became the business manager in 1918, of a publication known as ''The Rebel''. He married Llewella May Sonley on September 9, 1919. In 1920, he earned his Master of Arts

A Master of Arts ( la, Magister Artium or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA, M.A., AM, or A.M.) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Tho ...

degree from the University of Toronto, then joined the Classics department at the University of Alberta

The University of Alberta, also known as U of A or UAlberta, is a public research university located in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. It was founded in 1908 by Alexander Cameron Rutherford,"A Gentleman of Strathcona – Alexander Cameron Rutherfor ...

as a lecturer. He completed a Doctor of Philosophy

A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD, Ph.D., or DPhil; Latin: or ') is the most common Academic degree, degree at the highest academic level awarded following a course of study. PhDs are awarded for programs across the whole breadth of academic fields ...

degree at the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chicago is consistently ranked among the b ...

in 1922, studying Latin and Greek literature and archeology

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscap ...

. Hardy completed his dissertation in 1922 entitled ''Greek Epigrammatists at Rome in the First Century B.C.'', which was printed in the ''Journal of the Graduate School of Arts and Literature'' in 1923.

University professor career

Hardy received his professorship in 1922, then served as head of the Department of Classics at the University of Alberta from 1938 to 1964. He used the airwaves to educate about the Classics and world events, and gave 250 radio talks on

Hardy received his professorship in 1922, then served as head of the Department of Classics at the University of Alberta from 1938 to 1964. He used the airwaves to educate about the Classics and world events, and gave 250 radio talks on CBC Radio

CBC Radio is the English-language radio operations of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. The CBC operates a number of radio networks serving different audiences and programming niches, all of which (regardless of language) are outlined below ...

. He lectured on the Second Italo-Ethiopian War

The Second Italo-Ethiopian War, also referred to as the Second Italo-Abyssinian War, was a war of aggression which was fought between Italy and Ethiopia from October 1935 to February 1937. In Ethiopia it is often referred to simply as the Itali ...

and its background in 1935, and followed up later with a lecture on the challenges of fascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy an ...

. Other topics included the Greco-Roman world

The Greco-Roman civilization (; also Greco-Roman culture; spelled Graeco-Roman in the Commonwealth), as understood by modern scholars and writers, includes the geographical regions and countries that culturally—and so historically—were di ...

, and a series of talks about the world's first democracy.

Education system criticism

In April 1950, Hardy stated thatcompulsory education

Compulsory education refers to a period of education that is required of all people and is imposed by the government. This education may take place at a registered school or at other places.

Compulsory school attendance or compulsory schooling ...

in North America has resulted in "a sort of lowest common denominator of dull mediocrity", and "an under-educated and over-opinionated mass of people". He felt university students had weak English language skills, and had not been allowed to study what interested them. He stressed that educated needs to build an understanding of human relationships, instead of being technically trained persons.

In February 1954, Hardy wrote a series of six articles on education in Alberta

Education in Alberta is provided mainly through funding from the provincial government. The earliest form of formal education in Alberta is usually preschool which is not mandatory and is then followed by the partially-mandatory kindergarten t ...

, where he critiqued the value of education in the current Government of Alberta

The government of Alberta (french: gouvernement de l'Alberta) is the body responsible for the administration of the Canadian province of Alberta. As a constitutional monarchy, the Crown—represented in the province by the lieutenant governor—i ...

system. He questioned whether progressive education

Progressive education, or protractivism, is a pedagogical movement that began in the late 19th century and has persisted in various forms to the present. In Europe, progressive education took the form of the New Education Movement. The term ''pro ...

prepared young people for life, and argued it did not provide the basics such as mathematics, spelling, grammar, writing skills, general knowledge of history and geography. He specifically noted the lack of emphasis on the three Rs

The three Rs (as in the letter ''R'') are three basic skills taught in schools: reading, writing and arithmetic (usually said as "reading, 'riting, and 'rithmetic"). The phrase appears to have been coined at the beginning of the 19th century.

Th ...

.

Hardy felt that the increase in class sizes and the "watered-down lessons" led to students being less interested in their studies. He criticized the system for being designed to make it easier to pass, as a result of parents not wanting to see their child fail when others succeeded. He was critical of group projects geared towards the lowest common denominator, students developing poor thinking and working habits, and teachers being overwhelmed by the number of students. He felt that learning how to get along with other people was best achieved interacting with peers on the playground rather than in the classroom. He stated that children needed to learn facts and history about the world, to be able to interpret those facts as they grow in mental capacity. He stressed that proper learning was hard work, and the need for memorization skills in children when the ability for memory power was greatest. He noted that the progressive system admitted to not providing for the child with intellectual giftedness

Intellectual giftedness is an intellectual ability significantly higher than average. It is a characteristic of children, variously defined, that motivates differences in school programming. It is thought to persist as a trait into adult life, wi ...

, and was critical of the reduced requirements for entry into teacher's college

Teachers College, Columbia University (TC), is the graduate school of education, health, and psychology of Columbia University, a private research university in New York City. Founded in 1887, it has served as one of the official faculties ...

in Alberta.

The series of articles titled ''Education in Alberta'', were later printed in a booklet and made available by newspaper publishers in Alberta.

Hockey career

Early hockey career in Alberta

Hardy coached theAlberta Golden Bears

The Alberta Golden Bears and Pandas are the sports teams that represent the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. Alberta athletics teams have won a total of 93 national championships, including 79 U Sports sanctioned sports, making ...

men's ice hockey team from 1922 to 1926. He played a leading role in getting the first ice hockey rink

An ice hockey rink is an ice rink that is specifically designed for ice hockey, a competitive team sport. Alternatively it is used for other sports such as broomball, ringette, rinkball, and rink bandy. It is a rectangle with rounded corners and s ...

built at the University of Alberta campus in 1927. He served as president of the Alberta Amateur Hockey Association

Alberta ( ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is part of Western Canada and is one of the three prairie provinces. Alberta is bordered by British Columbia to the west, Saskatchewan to the east, the Northwest Territ ...

(AAHA) from 1931 to 1933, and was appointed to the board of governors for the Alberta branch of the Amateur Athletic Union of Canada The history of Canadian sports falls into five stages of development: early recreational activities before 1840; the start of organized competition, 1840–1880; the emergence of national organizations, 1882–1914; the rapid growth of both amateur ...

(AAU of C). During his tenure as president, the AAHA began hockey schools for its coaches and referees

A referee is an official, in a variety of sports and competition, responsible for enforcing the rules of the sport, including sportsmanship decisions such as ejection. The official tasked with this job may be known by a variety of other titl ...

. He supported expanding the playoffs for the intermediate division in senior ice hockey

Senior hockey refers to amateur or semi-professional ice hockey competition. There are no age restrictions for Senior players, who typically consist of those whose Junior eligibility has expired.

Senior hockey leagues operate under the jurisdict ...

, even though Canada did not yet have national playoffs for that division. At the AAU of C meeting in April 1933, he submitted a motion to allow the reinstatement of former professionals as amateurs, after a period of not playing professionally. The AAHA meeting in November 1933, reported the largest bank balance at end of year since the founding of the AAHA 26 years prior. Hardy submitted a resolution to have the AAU of C request to the 1936 Summer Olympics

The 1936 Summer Olympics (German: ''Olympische Sommerspiele 1936''), officially known as the Games of the XI Olympiad (German: ''Spiele der XI. Olympiade'') and commonly known as Berlin 1936 or the Nazi Olympics, were an international multi-sp ...

be taken away from Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

, due to Germany banning Jewish athletes. He was succeeded as president by Lance Morgan, and remained on the AAHA executive as past-president, representing the provincial body at national meetings.

Canadian Amateur Hockey Association

Second vice-president

Hardy was elected second vice-president of the

Hardy was elected second vice-president of the Canadian Amateur Hockey Association

The Canadian Amateur Hockey Association (CAHA; french: Association canadienne de hockey amateur) was the national governing body of amateur ice hockey in Canada from 1914 until 1994, when it merged with Hockey Canada. Its jurisdiction include ...

(CAHA) on April 4, 1934. He was re-elected by acclamation on April 13, 1935, and served as chairman of the resolutions committee. He also continued to serve on the AAHA executive, being re-elected in 1934, and 1935.

The CAHA decided in 1935 to appoint a special committee to study the definition of amateur and look into updating its wording to suit hockey in Canada. The special committee included Hardy, Cecil Duncan

Cecil Charles Duncan (February 1, 1893December 25, 1979) was a Canadian ice hockey administrator. He served as president of the Canadian Amateur Hockey Association (CAHA) from 1936 to 1938 and led reforms towards semi-professionalism in ice hoc ...

, George Dudley

George Samuel Dudley (April 19, 1894 – May 8, 1960) was a Canadian ice hockey administrator. He joined the Ontario Hockey Association (OHA) executive in 1928, served as its president from 1934 to 1936, and as its treasurer from 1936 to 1960 ...

and Clarence Campbell

Clarence Sutherland Campbell, (July 9, 1905 – June 24, 1984) was a Canadian ice hockey executive, referee, and soldier. He refereed in the National Hockey League (NHL) during the 1930s, served in the Canadian Army during World War II, then s ...

. The committee studied the issues encountered when the Halifax Wolverines

The Halifax Wolverines (sometimes; Halifax Wolves) were an amateur men's senior ice hockey team based in Halifax, Nova Scotia. The team won the 1935 Allan Cup, and were nominated to represent Canada in ice hockey at the 1936 Winter Olympics but ...

team which won the 1935 Allan Cup, was unable to represent the Canada men's national ice hockey team

The Canada men's national ice hockey team (popularly known as Team Canada; french: Équipe Canada) is the ice hockey team representing Canada inter ...

in ice hockey at the 1936 Winter Olympics

The men's ice hockey tournament at the 1936 Winter Olympics in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany, was the fifth Olympic Championship, also serving as the tenth World Championships and the 21st European Championships.

The British national ice h ...

due to financial issues related to amateur eligibility for the games.''Young, Scott (1989),'' p. 190

Hardy was in charge of CAHA playoffs for Western Canada

Western Canada, also referred to as the Western provinces, Canadian West or the Western provinces of Canada, and commonly known within Canada as the West, is a Canadian region that includes the four western provinces just north of the Canada� ...

, which included the Allan Cup

The Allan Cup is the trophy awarded annually to the national senior amateur men's ice hockey champions of Canada. It was donated by Sir Montagu Allan of Ravenscrag, Montreal, and has been competed for since 1909. The current champions are the ...

for the senior ice hockey divisions, and the Memorial Cup

The Memorial Cup () is the national championship of the Canadian Hockey League, a consortium of three major junior ice hockey leagues operating in Canada and parts of the United States. It is a four-team round-robin tournament played between t ...

for the junior ice hockey

Junior hockey is a level of competitive ice hockey generally for players between 16 and 21 years of age. Junior hockey leagues in the United States and Canada are considered amateur (with some exceptions) and operate within regions of each cou ...

divisions. In the 1936 Allan Cup playoffs, he ruled against including the Port Arthur Bearcats

The Port Arthur Bearcats (Bear Cats) were a senior amateur ice hockey team based in Port Arthur, Ontario, Canada – now part of the city of Thunder Bay – from the early 1900s until 1970. Before settling on the nickname of Bearca ...

. He stated it was too late to redraft the schedules, since the team had been overseas representing the Canada at the 1936 Winter Olympics instead of the Halifax Wolverines.

Hardy and Dudley presented the special committee's report on amateur status at the CAHA general meeting in April 1936, which came in the wake of Canada being beaten by the Great Britain men's national ice hockey team

The Great Britain men's national ice hockey team (also known as Team GB) is the national ice hockey team that represents the United Kingdom. A founding member of the International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF) in 1908, the team is control ...

for the gold medal at the 1936 Winter Olympics. They proposed four points to change the existing AAU of C definition.

The "four points" were:

# Hockey players may capitalize on their ability as hockey players for the purpose of obtaining legitimate employment.

# Hockey players may accept from their clubs or employers payment for time lost, from work while competing on behalf of their clubs. They will not however, be allowed to hold "shadow" jobs under the clause.

# Amateur hockey teams may play exhibition games against professional teams under such conditions as may be laid down by the individual branches of the CAHA.

# Professionals in another sport will be allowed to play under the CAHA jurisdiction as amateurs.

In presenting the reforms, Hardy stated, "it is time that we face present day realities as they exist in hockey across the country". The proposals stood to sever relations with the AAU of C as its governing body, and the CAHA's participation in international events. The ''Winnipeg Tribune

''The Winnipeg Tribune'' was a metropolitan daily newspaper serving Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada from January 28, 1890 to August 27, 1980. The paper was founded by R.L. Richardson and D.L. McIntyre who acquired the press and premises of the old '' ...

'' reported that when a vote came, the "old guard" would lose against updating the definition of an amateur. The four points were discussed at a special meeting with W. A. Fry

William Alexander Fry (September 7, 1872 – April 21, 1944) was a Canadian sports administrator and newspaper publisher. Fry founded the ''Dunnville Chronicle'' in 1896, managed local hockey and baseball teams in the 1910s, then served as pres ...

, the president of the AAU of C. Fry stated that the decision was "the most important matter ever to come before an amateur body in Canada". He sympathized with the situation since was a former CAHA president, but he did not support the changes. The CAHA voted to pass the resolution to adopt the new definition of amateur, and awaited a vote by the AAU of C on whether it would be accepted.

First vice-president

Hardy was elected first vice-president of the CAHA on May 6, 1936.''Canadian Amateur Hockey Association (1990)''. p. 127 He was delegated to assist Fry in conducting a mail-in vote on the CAHA proposals, and to draft a letter to send to AAU of C delegates. Fry published a letter to the CAHA in his ''

Hardy was elected first vice-president of the CAHA on May 6, 1936.''Canadian Amateur Hockey Association (1990)''. p. 127 He was delegated to assist Fry in conducting a mail-in vote on the CAHA proposals, and to draft a letter to send to AAU of C delegates. Fry published a letter to the CAHA in his ''Dunnville

Dunnville is an unincorporated community located near the mouth of the Grand River in Haldimand County, Ontario, Canada near the historic Talbot Trail. It was formerly an incorporated town encompassing the surrounding area with a total populat ...

Chronicle'' newspaper that defended the old definition of amateur, and said that no mail-in vote would be held, and deferred the issue to the AAU of C general meeting in November 1936. Hardy responded by asserting that Fry broke a promise to the CAHA, and maintained that the CAHA would go ahead with its plan, regardless of any AAU of C vote.

Hardy publicized the CAHA ambitions and published the article "Should We Revise Our Amateur Laws?" in ''Maclean's

''Maclean's'', founded in 1905, is a Canadian news magazine reporting on Canadian issues such as politics, pop culture, and current events. Its founder, publisher John Bayne Maclean, established the magazine to provide a uniquely Canadian perspe ...

'' on November 1, 1936. He argued for updating the definition of amateur, when it was commonly accepted to bend the rules in hockey. He felt that the AAU of C was hypocritical for classifying cricket

Cricket is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams of eleven players on a field at the centre of which is a pitch with a wicket at each end, each comprising two bails balanced on three stumps. The batting side scores runs by striki ...

, soccer

Association football, more commonly known as football or soccer, is a team sport played between two teams of 11 players who primarily use their feet to propel the ball around a rectangular field called a pitch. The objective of the game is ...

, and tennis

Tennis is a racket sport that is played either individually against a single opponent ( singles) or between two teams of two players each ( doubles). Each player uses a tennis racket that is strung with cord to strike a hollow rubber ball ...

as pastime sports where athletes may compete with or against professionals and still be called amateurs. He sought for these inconsistencies with respect to professionals and amateurs should be "ironed out and a common-sense view be taken of the situation". He further stated that the old definition of amateur came "from the days when only gentlemen with independent means were supposed to engage in sport"; and that in the era of the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

, it was justified that a hockey player be allowed legitimate employment in sport and be compensated for work lost while away at playoffs or representing his country at international events.

The amateur issue achieved significant press coverage by November 1936. Canadian journalist Scott Young wrote that public perception was against the AAU of C definition, and that Canadians were in favour of amateurs being compensated for travel, which was perceived as a reason for Canada not winning the gold medal in ice hockey at the 1936 Winter Olympics. Hardy and Dudley presented their arguments at the AAU of C general meeting, and reiterated that the CAHA would not back down since the changes were in the best interests of hockey in Canada. Hardy felt that defending the interests of players in Canada was more important than maintaining international relations. The AAU of C voted and approved exhibition games between amateurs and professionals, but rejected the other three points.

The status of the alliance between the CAHA and the AAU of C was left in limbo and unclear. Hardy remained open to a relationship with the AAU of C, and denied a report in ''The Gazette

The Gazette (stylized as the GazettE), formerly known as , is a Japanese visual kei Rock music, rock band, formed in Kanagawa Prefecture, Kanagawa in early 2002.''Shoxx'' Vol 106 June 2007 pg 40-45 The band is currently signed to Sony Music Recor ...

'' that the CAHA had formally severed ties. In March 1937, the Amateur Athletic Union

The Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) is an amateur sports organization based in the United States. A multi-sport organization, the AAU is dedicated exclusively to the promotion and development of amateur sports and physical fitness programs. It has ...

of the United States terminated its affiliation agreement with the CAHA due to the split with the AAU of C. Hardy was not deterred since it meant fewer players going to the United States and depleting rosters in Canada.

In other business, Hardy defended the decision to reduce the expenses covered for delegates to attend the CAHA meeting, and spend the money instead on grants to the provincial branches to promote minor ice hockey

Minor hockey is an umbrella term for amateur ice hockey which is played below the junior age level. Players are classified by age, with each age group playing in its own league. The rules, especially as it relates to body contact, vary from cla ...

, junior ice hockey, and expenses for the Canadian national team at the Olympics. He anticipated that eastern Canadian teams may start an intermediate level championship, and he was re-elected to the AAHA executive.

Hardy was re-elected first vice-president of the CAHA, on April 20, 1937, and supervised playoffs schedules for Western Canada. The CAHA profited C$17,000 from the 1938 playoffs. National registrations had increased 4,500 players in three seasons, which justified giving the grants to promote minor ice hockey. By 1938, profits had improved the financial reserves of the CAHA from $5,000 to $50,000.

In February 1938, National Hockey League

The National Hockey League (NHL; french: Ligue nationale de hockey—LNH, ) is a professional ice hockey league in North America comprising 32 teams—25 in the United States and 7 in Canada. It is considered to be the top ranked professional ...

(NHL) president Frank Calder

Frank Sellick Calder (November 17, 1877 – February 4, 1943) was a British-born Canadian ice hockey executive, journalist, and athlete.

Calder was the first president of the National Hockey League (NHL), from 1917 until his death in 1943. He ...

terminated the working agreement with the CAHA, after a player suspended by the NHL was registered by a CAHA team. Hardy met with Calder and felt that issues were worked out, but Calder told NHL teams that they could approach any junior player with a contract offer. Hardy then set up a committee including himself, Dudley and W. A. Hewitt

William Abraham Hewitt (May 15, 1875September 8, 1966) was a Canadian sports executive and journalist, also widely known as Billy Hewitt. He was secretary of the Ontario Hockey Association (OHA) from 1903 to 1966, and sports editor of the ''To ...

to represent the CAHA at a meeting with the NHL to discuss the issues.

President

=First term

= Hardy was elected president of the CAHA on April 18, 1938, succeeding Cecil Duncan. Hardy reached a new working agreement with the NHL in August 1938. The CAHA agreed not to allow international transfers for players on NHL reserve lists, and the NHL agreed not to sign any junior players without permission. It also included provisions against the exodus of Canadian players to American clubs, and stipulated that both organizations use the same playing rules, and recognize each other's suspensions. Hardy then represented the CAHA at the joint rules committee to draft uniform rules with the NHL. Hardy set out to negotiate a working agreement with theAmateur Hockey Association of the United States

USA Hockey is the national ice hockey organization in the United States. It is recognized by the International Olympic Committee and the United States Olympic & Paralympic Committee as the governing body for organized ice hockey in the United S ...

(AHAUS), which had been founded in 1937 by Tommy Lockhart

Thomas Finan Lockhart (March 21, 1892 – May 18, 1979) was an American ice hockey administrator, business manager, and events promoter. He was president of the Eastern Hockey League from 1933 to 1972, and was the founding president of the Amat ...

as a new governing body for ice hockey in the United States. Hardy reached a two-year agreement with AHAUS in September 1938. It regulated games played between amateur teams in Canada and the United States, set out provisions for transfers from one organization to the other, and recognized each other's suspensions and authority. Hardy cautioned Canadians against signing contracts with the Tropical Hockey League

The Tropical Hockey League (THL) was a short-lived ice hockey minor league in Miami, Florida. The initial league had four teams, all based in Miami, and lasted for only one season, 1938–39, before folding; it was briefly resurrected in 1940 bef ...

based in Miami

Miami ( ), officially the City of Miami, known as "the 305", "The Magic City", and "Gateway to the Americas", is a East Coast of the United States, coastal metropolis and the County seat, county seat of Miami-Dade County, Florida, Miami-Dade C ...

, since the league was not affiliated with AHAUS.

In February 1939, the Amateur Athletic Union of the United States responded to the CAHA affiliation with AHAUS by protesting to the Ligue Internationale de Hockey sur Glace (LIHG). The Amateur Athletic Union did not recognize the authority of AHAUS within the United States, and disagreed any fellow LIHG members entering into agreements with the new governing body. Hardy stated that the CAHA would stay true to the agreement with AHAUS, which he referred to as the most comprehensive ice hockey governing body in the United States. His decision potentially meant that the CAHA would lose its membership in the LIHG, and not be permitted to compete at the Ice Hockey World Championships

The Ice Hockey World Championships are an annual international men's ice hockey tournament organized by the International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF). First officially held at the 1920 Summer Olympics, it is the sport's highest profile annua ...

or in ice hockey at the Olympic Games

Ice hockey tournaments have been staged at the Olympic Games since 1920. The men's tournament was introduced at the 1920 Summer Olympics and was transferred permanently to the Winter Olympic Games program in 1924, in France. The women's tournam ...

.

Hardy met with officials from the AAHA and the Saskatchewan Amateur Hockey Association in February 1939, to discuss the cost of developing players lost to professional teams. They agreed to propose a draft fee when a CAHA player signed an NHL contract to offset financial losses. In the same month, Hardy negotiated to include the British Ice Hockey Association

Ice Hockey UK (IHUK) is the national governing body of ice hockey in the United Kingdom. Affiliated to the International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF), IHUK is the internationally recognised umbrella body in the United Kingdom. IHUK was created ...

(BIHA) into the existing agreement with AHAUS to regulate imported players. The announcement upheld his previous statement that anyone who had played with the BIHA would need to seek a proper transfer back to Canada, or face suspension.

In other business, Hardy announced more grants to provincial branches to promote minor ice hockey, he arranged the Western intermediate senior playoffs, and spoke on national radio about developments in the status of amateur sport in Canada.

Hardy's first term as president ended with the CAHA's silver jubilee celebrations. He appointed Claude C. Robinson to oversee the event in Winnipeg

Winnipeg () is the capital and largest city of the province of Manitoba in Canada. It is centred on the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine rivers, near the longitudinal centre of North America. , Winnipeg had a city population of 749,6 ...

, to recognize the contributions of the Manitoba Amateur Hockey Association (MAHA) in starting the CAHA. The gala was hosted at the Royal Alexandra Hotel

Royal may refer to:

People

* Royal (name), a list of people with either the surname or given name

* A member of a royal family

Places United States

* Royal, Arkansas, an unincorporated community

* Royal, Illinois, a village

* Royal, Iowa, a ci ...

on April 11, 1939. Hardy acknowledged the guidance of Robinson as a founding father of the CAHA in his opening remarks, and stated that "we must have the vision of today, also of the future, and also of the past". He felt the future goals of the CAHA should be, "the development of youths who will fight hard, but fight clean".

=Second term

= Hardy was re-elected president of the CAHA on April 12, 1939. He continued the affiliation with AHAUS, in objection to the protest by the Amateur Athletic Union of the United States. He received a letter from LIHG president

Hardy was re-elected president of the CAHA on April 12, 1939. He continued the affiliation with AHAUS, in objection to the protest by the Amateur Athletic Union of the United States. He received a letter from LIHG president Paul Loicq

Paul Loicq (11 August 1888 – 26 March 1953) was a Belgian lawyer, businessman and ice hockey player, coach, referee and administrator. He played ice hockey for Belgium men's national ice hockey team and won four bronze medals from in 1910 to 1 ...

which permitted continued negotiations with AHAUS. Hardy reported that the intermediate playoffs which he started in Western Canada were becoming profitable. He extended more grants to promote minor ice hockey within Canada, and to the Quebec Amateur Hockey Association

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirtee ...

(QAHA) to translate playing rules into the French language

French ( or ) is a Romance language of the Indo-European family. It descended from the Vulgar Latin of the Roman Empire, as did all Romance languages. French evolved from Gallo-Romance, the Latin spoken in Gaul, and more specifically in Nor ...

. The CAHA executive felt it was in a good financial situation and felt it appropriate to help the Canadian Olympic Association

The Canadian Olympic Committee (COC; french: Comité olympique canadien) is a private, non-profit organization that represents Canada at the International Olympic Committee (IOC). It is also a member of the Pan American Sports Organization ( ...

. Hardy announced a grant of $3000 towards travel expenses for teams to the 1940 Winter Olympics

The 1940 Winter Olympics, which would have been officially known as the and as Sapporo 1940 (札幌1940), were to have been celebrated from 3 to 12 February 1940 in Sapporo, Japan, but the games were eventually cancelled due to the onset of Wo ...

. He explained CAHA financial policy was to keep enough funds at hand in case of years with deficits, to take care of playoffs travel expenses for its teams, to pay administration costs, and to reinvest profits into youth hockey for the future.

The CAHA proposed having junior hockey contracts which tied a player to a team, as a means to prevent rosters being raided by professional teams, and to protect the junior teams against not being reimbursed for developing the player. The proposed contract required a $500 release fee to be paid when a player signed by any professional club. Hardy said the contracts would put the CAHA in a good legal position with respect to the relationship with its players. He also supported refusing transfers for players who had been offered a reasonable contract of $75 to $125 per month. In June 1939, the CAHA formally notified the NHL of the request for development fees after the existing deal expired in 1940.

When World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

began, the Government of Canada

The government of Canada (french: gouvernement du Canada) is the body responsible for the federal administration of Canada. A constitutional monarchy, the Crown is the corporation sole, assuming distinct roles: the executive, as the ''Crown ...

wanted sports to continue, and maintain morale of the people during war time. Hardy announced that the CAHA would operate its normal schedule and playoffs for the Allan Cup and Memorial Cup, and stated that the CAHA would provide any services needed. The residency rule was waived for those engaged in military service, and military hockey teams became eligible for the Allan Cup playoffs. The CAHA welcomed any professional players who entered military service with consent of the NHL, and drafted plans to replace players lost to military service. Hardy asked that the provincial hockey associations incorporate military teams into schedules, and assist in running leagues for garrison

A garrison (from the French ''garnison'', itself from the verb ''garnir'', "to equip") is any body of troops stationed in a particular location, originally to guard it. The term now often applies to certain facilities that constitute a mil ...

units.

At the general meeting in 1940, Hardy stated a desire to continue the existing agreement with the NHL, as long as professional teams did not sign junior-aged players. Teams in the CAHA were given the option of making player contracts for the upcoming season. The AAU of C decided in 1938 to adopt the definition of amateur as laid out by the respective world governing body of each sport as recognized by the International Olympic Committee

The International Olympic Committee (IOC; french: link=no, Comité international olympique, ''CIO'') is a non-governmental sports organisation based in Lausanne, Switzerland. It is constituted in the form of an association under the Swiss ...

(IOC). The CAHA declined the request from the AAU of C to re-affiliate. The CAHA stance on amateurs was solidified, and its constitution was updated to define an amateur player as one who, "either has not engaged or is not engaged in organized professional hockey".

Past-president

George Dudley succeeded Hardy as president of the CAHA in April 1940. Hardy served as past-president until 1942, and was re-elected to the AAHA executive. He was chairman of the CAHA's player committee, which considered whether permission could be given for the NHL to sign juniors. He remained in charge of the Western Canada playoffs for the CAHA; and he and Dudley met with QAHA officials in 1941, to approve a plan which gave control of theEastern Canada

Eastern Canada (also the Eastern provinces or the East) is generally considered to be the region of Canada south of the Hudson Bay/Strait and east of Manitoba, consisting of the following provinces (from east to west): Newfoundland and Labrador, ...

playoffs for the Allan Cup and Memorial Cup to a subcommittee of the CAHA.

International Ice Hockey Association

Foundation of the association

On April 15, 1940, in Montreal, the CAHA and AHAUS agreed to form a new governing body known tentatively as the International Ice Hockey League, and invited the BIHA to join. Hardy who was also the CAHA president, stated that "the purpose of the new association is to promote the game of hockey among the threeAnglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons were a Cultural identity, cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of the Anglo- ...

nations". The new body became known as the International Ice Hockey Association

The International Ice Hockey Association was a governing body for international ice hockey. It was established in 1940 when the Canadian Amateur Hockey Association wanted more control over international hockey, and was in disagreement with the ...

, and Hardy as its president from 1940 to 1947. Lockhart from AHAUS was named first vice-president, and the BIHA was asked to nominate the second vice-president position.

Hardy explained the International Ice Hockey Association as a means of shifting the control of world hockey from Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

to Canada, "where it rightfully belonged". He also noted the inactivity of the LIHG resulting from World War II. He sought for acceptance by the IOC on terms acceptable to the CAHA. A constitution for the new association was delegated to a committee including future CAHA presidents Hanson Dowell

Hanson Taylor Dowell (September 14, 1906September 23, 2000) was a Canadian ice hockey administrator and politician. He served as president of the Canadian Amateur Hockey Association from 1945 to 1947, and was the first person from the Maritime ...

and W. B. George

William Bryden George (November 28, 1899June 25, 1972), also known as Baldy George, was a Canadian sports administrator and agriculturalist. He was president of the Canadian Amateur Hockey Association from 1952 to 1955, when Canada debated whe ...

, and MAHA president Vic Johnson. The constitution stated that the associations president must be an executive officer or a past-president of the CAHA. The CAHA gave $500 to the association, and an honorarium to Hardy for expenses.

Professional–amateur relations

Amateur and junior hockey teams in Canada were upset about losing players to professional leagues without compensation, and Hardy set about to negotiate reimbursement of the Canadian teams when a player became professional. The CAHA had introduced player contracts for the 1940–41 season, with the goal to keep junior-aged and amateur players under service in Canada instead of leaving for professional leagues. In September 1940, Hardy announced a one-year agreement was reached with the NHL to reimburse the amateur associations, which included $250 for signing an amateur and another $250 if the amateur played in the NHL. The new professional-amateur agreement was signed by Calder on behalf of the NHL in October 1940, and also applied to leagues in the BIHA and the Eastern Amateur Hockey League in the United States. The distribution of the development funds from the NHL was based on the service time the amateur had with each respective club, and was overseen by Hardy and Frank Sargent. The agreement included allowing the NHL to sign a limited number of junior age players. Hardy decided on disputes of players becoming professionals, and reinstatements as amateurs. He committed to decide on all application within 15 days to expedite transfers and reinstatements due to wartime enlistments and travel restrictions. He stated, "we believe that the movement between professional and amateur ranks should be made as easy as possible", which included former professionals being welcomed back in amateur. By January 1941, both Hardy and Calder agreed that amateur and professional organizations were at a "perfect understanding" and were co-operating closely. By 1942, the agreement had brought in $17,241 in development fees to junior teams. Demand for junior-aged players during the1941–42 NHL season

The 1941–42 NHL season was the 25th season of the National Hockey League. Seven teams played 48 games each. The Toronto Maple Leafs would win the Stanley Cup defeating the Detroit Red Wings winning four straight after losing the first three in ...

was higher due to war-time travel restrictions on older players. Calder reported there was a general agreement with the amateur leagues that a junior-aged player should be able to determine his own financial future due to the war.

In 1943, Hardy recommended adjustments in amateur payments for players becoming professional, since many later enlisted shortly after signing a contract. He felt that under normal circumstances, junior-aged players should not be signed to professional contracts. He negotiated wartime measures with the NHL, without opposition being raised by presidents of the provincial associations. The Pacific Coast Hockey League

The Pacific Coast Hockey League was an ice hockey minor league with teams in the western United States and western Canada that existed in several incarnations: from 1928 to 1931, from 1936 to 1941, and from 1944 to 1952.

PCHL 1928–1931

The firs ...

began in 1944, and competed for junior-aged players. Hardy ruled that since the league operated under affiliation with AHAUS, the existing international transfer rules and professional–amateur agreement would apply to the new league.

In April 1943,

In April 1943, The Canadian Press

The Canadian Press (CP; french: La Presse canadienne, ) is a Canadian national news agency headquartered in Toronto, Ontario. Established in 1917 as a vehicle for the time's Canadian newspapers to exchange news and information, The Canadian Pre ...

reported that Hardy was rumoured to be appointed president of the NHL, to replace Red Dutton

Norman Alexander Dutton (July 23, 1897 – March 15, 1987) was a Canadian ice hockey player, coach and executive. Commonly known as Red Dutton, and earlier by the nickname "Mervyn", he played for the Calgary Tigers of the Western Canada Hockey ...

who had been acting president since the death of Calder in 1943. Hardy stated that he had not been formally approached by the NHL. In October 1944, Lester Patrick

Curtis Lester Patrick (December 31, 1883 – June 1, 1960) was a Canadian professional ice hockey player and coach associated with the Victoria Aristocrats/Cougars of the Pacific Coast Hockey Association (Western Hockey League after 1924), and t ...

sponsored Hardy to be president. "He is an ideal man for the job. He is temperamentally suited and has an excellent record as an executive of the CAHA". Patrick credited Hardy for being largely responsible for the current working agreement between the NHL and amateur associations. Hardy "warmly appreciated the nice things Lester Patrick" said, but declined further comment.

In April 1945, Hardy was re-elected president of the International Ice Hockey Association. By 1946, the professional–amateur agreement provided more than $45,000 in development fees. The association and the NHL agreed to enforce suspensions for players not fulfilling a tryout contract. Hardy then declined transfers to those under such a contract.

In May 1946, the NHL proposed a flat payment of $20,000 to cover all players being signed to professional contracts, whereas the CAHA requested $2,000 for any player remaining in the NHL for more than a year. Hardy felt the CAHA was at a disadvantage to press too hard, and wanted to maintain good relations with the NHL and AHAUS. The flat rate offer was later accepted with the stipulation that a junior-aged player could sign a contract at age 16, but not play professional until age 18.

In January 1947, the CAHA and AHAUS disagreed over a $100 transfer fee requested for players going to the United States. Lockhart refused the fee, stating the CAHA had no authority to make that request. He also threatened to resign as vice-president and withdraw AHAUS from the association. Several players had left Canada without proper documentation, but Hardy ultimately allowed the players to remain in the United States.

World hockey relations

At the 1944 CAHA general meeting inMontreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-most populous city in Canada and List of towns in Quebec, most populous city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian ...

, a motion was passed to sever relations with the LIHG. Another a motion of confidence was passed in the International Ice Hockey Association, and closer relationships between the CAHA, AHAUS and the BIHA.

In April 1945, Hardy envisioned an amateur hockey World Series after World War II, involving teams from Canada, the United States, England and Scotland. The proposed series would be an annual event between the North American and European champion to begin in 1947 or 1948.

Hardy expected hockey to grow after the war, and said proper rules had been established to limited transfers and prevent raiding of Canadian rosters. He expected a large number of Canadian soldiers stationed in Europe to remain there playing hockey. Post-war plans were discussed on how to co-ordinate classification of clubs for international competition. In May 1946, the Swedish Ice Hockey Association

The Swedish Ice Hockey Association ( sv, Svenska Ishockeyförbundet (SIF)) in Swedish, is an association of Swedish ice hockey clubs. It was established in Stockholm on 17 November 1922 by representatives from seven clubs. Before then, organized ...

and French Ice Hockey Federation

The French Ice Hockey Federation (french: Fédération française de hockey sur glace (FFHG)) is the governing body of ice hockey in France, as recognized by the International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF). It was founded in 2006 after separation w ...

expressed interest in joining the association.

Merger with the LIHG

The association met in August 1946 inNew York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...