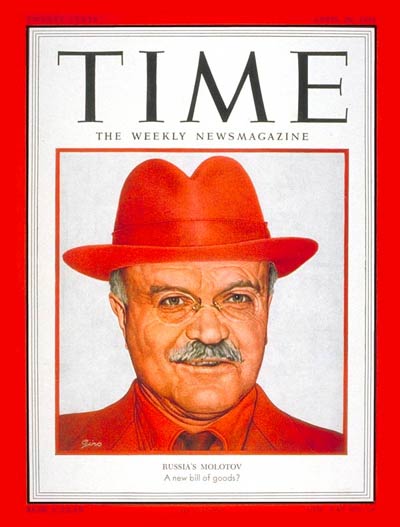

Vyacheslav Molotov on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

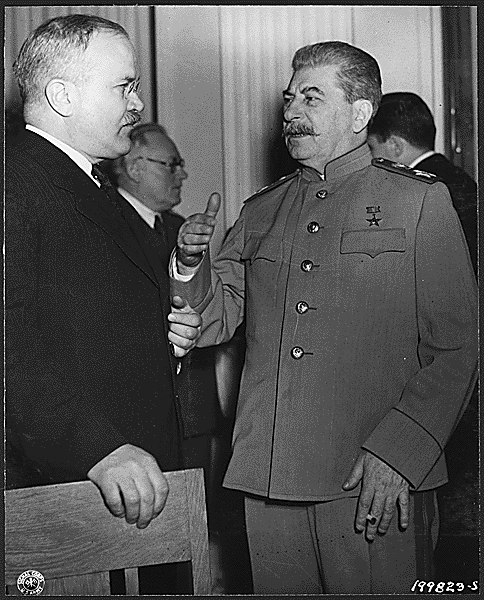

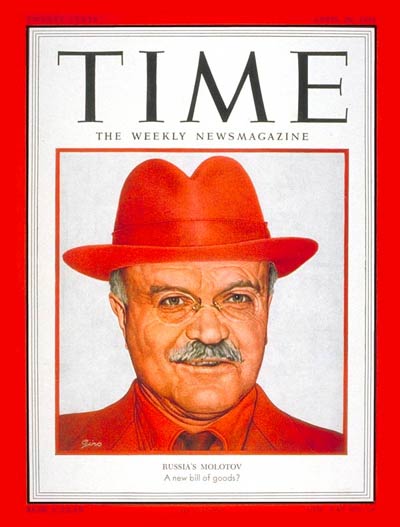

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov. ; (;. 9 March O._S._25_February.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O. S. 25 February">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O. S. 25 February1890 – 8 November 1986) was a Russian politician and diplomat, an Old Bolshevik, and a leading figure in the Soviet government from the 1920s onward. He served as Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars from 1930 to 1941 and as Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Soviet Union), Minister of Foreign Affairs from 1939 to 1949 and from 1953 to 1956.

During the 1930s, he ranked second in the Soviet leadership, after

Molotov was born Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Skryabin in the village of

Molotov was born Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Skryabin in the village of  Molotov worked as a so-called "professional revolutionary" for the next several years, wrote for the party press, and attempted to improve the organisation of the underground party. He moved from St. Petersburg to Moscow in 1914 at the outbreak of the

Molotov worked as a so-called "professional revolutionary" for the next several years, wrote for the party press, and attempted to improve the organisation of the underground party. He moved from St. Petersburg to Moscow in 1914 at the outbreak of the  In 1918, Molotov was sent to Ukraine to take part in the

In 1918, Molotov was sent to Ukraine to take part in the  During the power struggles after

During the power struggles after

Addressing a Moscow communist party conference on 23 February 1929, Molotov emphasised the need to undertake "the most rapid possible growth of industry" both for economic reasons and because, he claimed, the Soviet Union was in permanent, imminent danger of attack. The argument over how fast to expand industry was behind the rift between Stalin and the right, led by Bukharin and Rykov, who feared that too rapid a pace would cause economic dislocation. With their defeat, Molotov emerged as the second most powerful figure in the Soviet Union. During the Central Committee plenum of 19 December 1930, Molotov succeeded

Addressing a Moscow communist party conference on 23 February 1929, Molotov emphasised the need to undertake "the most rapid possible growth of industry" both for economic reasons and because, he claimed, the Soviet Union was in permanent, imminent danger of attack. The argument over how fast to expand industry was behind the rift between Stalin and the right, led by Bukharin and Rykov, who feared that too rapid a pace would cause economic dislocation. With their defeat, Molotov emerged as the second most powerful figure in the Soviet Union. During the Central Committee plenum of 19 December 1930, Molotov succeeded

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

, whom he supported loyally for over 30 years, and whose reputation he continued to defend after Stalin's death, having himself been deeply implicated in the worst atrocities of the Stalin years – the forced collectivisation of agriculture in the early 1930s, and the Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Nikolay Yezhov, Yezhov'), was General ...

, during which he signed 373 lists of people condemned to execution.

As People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs

The Ministry of External Relations (MER) of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) (russian: Министерство иностранных дел СССР) was founded on 6 July 1923. It had three names during its existence: People's Co ...

in August 1939, Molotov became the principal Soviet signatory of the German–Soviet non-aggression pact

A non-aggression pact or neutrality pact is a treaty between two or more states/countries that includes a promise by the signatories not to engage in military action against each other. Such treaties may be described by other names, such as a tr ...

, also known as the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was a non-aggression pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union that enabled those powers to partition Poland between them. The pact was signed in Moscow on 23 August 1939 by German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ri ...

. He retained his place as a leading Soviet diplomat and politician until March 1949, when he fell out of Stalin's favour and lost the foreign affairs ministry leadership to Andrei Vyshinsky

Andrey Yanuaryevich Vyshinsky (russian: Андре́й Януа́рьевич Выши́нский; pl, Andrzej Wyszyński) ( – 22 November 1954) was a Soviet politician, jurist and diplomat.

He is known as a state prosecutor of Joseph S ...

. Molotov's relationship with Stalin deteriorated further, and Stalin criticised Molotov in a speech to the 19th Party Congress.

Molotov was reappointed Minister of Foreign Affairs after Stalin's death in 1953 but staunchly opposed Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

's de-Stalinization

De-Stalinization (russian: десталинизация, translit=destalinizatsiya) comprised a series of political reforms in the Soviet Union after the death of long-time leader Joseph Stalin in 1953, and the thaw brought about by ascension ...

policy, which resulted in his eventual dismissal from all positions and expulsion from the party in 1961 (after numerous unsuccessful petitions, Molotov was readmitted in 1984). Molotov defended Stalin's policies and legacy until his death in 1986 and harshly criticised Stalin's successors, especially Khrushchev.

The improvised incendiary weapon known as the Molotov cocktail

A Molotov cocktail (among several other names – ''see other names'') is a hand thrown incendiary weapon constructed from a frangible container filled with flammable substances equipped with a fuse (typically a glass bottle filled with flamma ...

is named after him.

Early life and career

Kukarka

Sovetsk (russian: Сове́тск), formerly Kukarka (russian: Кука́рка; chm, Кукарка), is a town and the administrative center of Sovetsky District in Kirov Oblast, Russia. Population:

Etymology

The origins of the name "Kuk ...

, Yaransk

Yaransk (russian: Яра́нск; chm, Яраҥ, ''Yaraň'') is a town and the administrative center of Yaransky District in Kirov Oblast, Russia, located on the Yaran River ( Vyatka's basin), southwest of Kirov, the administrative center ...

Uyezd

An uezd (also spelled uyezd; rus, уе́зд, p=ʊˈjest), or povit in a Ukrainian context ( uk, повіт), or Kreis in Baltic-German context, was a type of administrative subdivision of the Grand Duchy of Moscow, the Russian Empire, and the ea ...

, Vyatka Governorate

Vyatka Governorate (russian: Вятская губерния, udm, Ватка губерний, mhr, Виче губерний, tt-Cyrl, Вәтке губернасы) was a governorate of the Russian Empire and Russian Soviet Federative Socia ...

(now Sovetsk, Kirov Oblast

Kirov Oblast (russian: Ки́ровская о́бласть, ''Kirovskaya oblast'') is a federal subject of Russia (an oblast) in Eastern Europe. Its administrative center is the city of Kirov. Population: 1,341,312 ( 2010 Census).

Geography

Na ...

), the son of a merchant. Contrary to a commonly-repeated error, he was not related to the composer Alexander Scriabin

Alexander Nikolayevich Scriabin (; russian: Александр Николаевич Скрябин ; – ) was a Russian composer and virtuoso pianist. Before 1903, Scriabin was greatly influenced by the music of Frédéric Chopin and composed ...

.

Throughout his teenager years, he was described as "shy" and "quiet" and always assisted his father with his business. He was educated at a secondary school in Kazan

Kazan ( ; rus, Казань, p=kɐˈzanʲ; tt-Cyrl, Казан, ''Qazan'', IPA: ɑzan is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Tatarstan in Russia. The city lies at the confluence of the Volga and the Kazanka rivers, covering a ...

, where he became friends with fellow revolutionary Aleksandr Arosev

Aleksander Yakovlevich Arosev (Russian: Алекса́ндр Я́ковлевич Аро́сев; 25 May (6 June) 1890, Kazan – 10 February 1938, Moscow) was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet diplomat and writer.

Biography

Arosev was born in to ...

. Molotov joined the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP; in , ''Rossiyskaya sotsial-demokraticheskaya rabochaya partiya (RSDRP)''), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party or the Russian Social Democratic Party, was a socialist pol ...

(RSDLP) in 1906, and soon gravitated toward the organisation's radical Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

faction, which was led by Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 19 ...

.Roberts, Geoffrey (2012). ''Molotov: Stalin's Cold Warrior''. Washington, DC: Potomac Books. p. 5.

Skryabin took the pseudonym "Molotov", derived from the Russian word ''molot'' (sledge hammer) since he believed that the name had an "industrial" and "proletarian" ring to it. He was arrested in 1909 and spent two years in exile in Vologda

Vologda ( rus, Вологда, p=ˈvoləɡdə) is a city and the administrative center of Vologda Oblast, Russia, located on the river Vologda within the watershed of the Northern Dvina. Population:

The city serves as a major transport hu ...

.

In 1911, he enrolled at St. Petersburg Polytechnic Institute. Molotov joined the editorial staff of a new underground Bolshevik newspaper, ''Pravda

''Pravda'' ( rus, Правда, p=ˈpravdə, a=Ru-правда.ogg, "Truth") is a Russian broadsheet newspaper, and was the official newspaper of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, when it was one of the most influential papers in the co ...

'', and met Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

for the first time in association with the project.Roberts, Geoffrey (2012). ''Molotov: Stalin's Cold Warrior''. Washington, DC: Potomac Books. p. 6. That first association between the two future Soviet leaders proved to be brief, however, and failed to lead to an immediate close political association.

Molotov worked as a so-called "professional revolutionary" for the next several years, wrote for the party press, and attempted to improve the organisation of the underground party. He moved from St. Petersburg to Moscow in 1914 at the outbreak of the

Molotov worked as a so-called "professional revolutionary" for the next several years, wrote for the party press, and attempted to improve the organisation of the underground party. He moved from St. Petersburg to Moscow in 1914 at the outbreak of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. It was in Moscow the following year that Molotov was again arrested for his party activity and was this time deported to Irkutsk

Irkutsk ( ; rus, Иркутск, p=ɪrˈkutsk; Buryat language, Buryat and mn, Эрхүү, ''Erhüü'', ) is the largest city and administrative center of Irkutsk Oblast, Russia. With a population of 617,473 as of the 2010 Census, Irkutsk is ...

, in eastern Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part of ...

. In 1916, he escaped from his Siberian exile and returned to the capital city, which had been renamed Petrograd by the Tsarist regime since it thought that the old name sounded too German.

Molotov became a member of the Bolshevik Party's committee in Petrograd

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

in 1916. When the February Revolution

The February Revolution ( rus, Февра́льская револю́ция, r=Fevral'skaya revolyutsiya, p=fʲɪvˈralʲskəjə rʲɪvɐˈlʲutsɨjə), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and somet ...

occurred in 1917, he was one of the few Bolsheviks of any standing in the capital. Under his direction ''Pravda

''Pravda'' ( rus, Правда, p=ˈpravdə, a=Ru-правда.ogg, "Truth") is a Russian broadsheet newspaper, and was the official newspaper of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, when it was one of the most influential papers in the co ...

'' took to the "left" to oppose the Provisional Government formed after the revolution. When Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

returned to the capital, he reversed Molotov's line, but when Lenin arrived, he overruled Stalin. However, Molotov became a protégé of and a close adherent to Stalin, an alliance to which he owed his later prominence. Molotov became a member of the Military Revolutionary Committee

The Military Revolutionary Committee (russian: Военно-революционный комитет, ) was the name for military organs created by the Bolsheviks under the soviets in preparation for the October Revolution (October 1917 – Marc ...

, which planned the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key moment ...

and effectively brought the Bolsheviks to power.

In 1918, Molotov was sent to Ukraine to take part in the

In 1918, Molotov was sent to Ukraine to take part in the Russian Civil War

, date = October Revolution, 7 November 1917 – Yakut revolt, 16 June 1923{{Efn, The main phase ended on 25 October 1922. Revolt against the Bolsheviks continued Basmachi movement, in Central Asia and Tungus Republic, the Far East th ...

, which had broken out. Since he was not a military man, he took no part in the fighting. In summer 1919, he was sent on a tour by steamboat of the Volga

The Volga (; russian: Во́лга, a=Ru-Волга.ogg, p=ˈvoɫɡə) is the List of rivers of Europe#Rivers of Europe by length, longest river in Europe. Situated in Russia, it flows through Central Russia to Southern Russia and into the Cas ...

and Kama

''Kama'' (Sanskrit ) means "desire, wish, longing" in Hindu, Buddhist, Jain, and Sikh literature.Monier Williamsकाम, kāmaMonier-Williams Sanskrit English Dictionary, pp 271, see 3rd column Kama often connotes sensual pleasure, sexual ...

rivers, with Lenin's wife, Nadezhda Krupskaya to spread Bolshevik propaganda. On his return, he was appointed chairman of the Nizhny Novgorod

Nizhny Novgorod ( ; rus, links=no, Нижний Новгород, a=Ru-Nizhny Novgorod.ogg, p=ˈnʲiʐnʲɪj ˈnovɡərət ), colloquially shortened to Nizhny, from the 13th to the 17th century Novgorod of the Lower Land, formerly known as Gork ...

provincial executive, where the local party passed a vote of censure against him, for his alleged fondness for intrigue. He was transferred to Donetsk

Donetsk ( , ; uk, Донецьк, translit=Donets'k ; russian: Донецк ), formerly known as Aleksandrovka, Yuzivka (or Hughesovka), Stalin and Stalino (see also: Names of European cities in different languages (C–D), cities' alternat ...

, and in November 1920, he became secretary to the Central Committee of the Ukrainian Bolshevik Party and married the Soviet politician Polina Zhemchuzhina

Polina Semyonovna Zhemchuzhina (born Perl Solomonovna Karpovskaya; 27 February 1897 – 1 April 1970) was a Soviet politician and the wife of the Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov. Zhemchuzhina was the director of the Soviet national ...

.

Lenin recalled Molotov to Moscow in 1921, elevated him to full membership of the Central Committee and Orgburo

The Orgburo (russian: Оргбюро́), also known as the Organisational Bureau (russian: организационное бюро), of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union existed from 1919 to 1952, when it was a ...

, and put him in charge of the party secretariat. Molotov was voted in as a non-voting member of the Politburo in 1921 and held the office of Responsible Secretary. Alexander Barmine

Alexander Grigoryevich Barmin (russian: Александр Григорьевич Бармин, ''Aleksandr Grigoryevich Barmin''; August 16, 1899 – December 25, 1987), most commonly Alexander Barmine, was an officer in the Soviet Army and dipl ...

, a minor communist official, visited Molotov in his office near the Kremlin while he was running the secretariat, and remembered him as having "a large and placid face, the face of an ordinary, uninspired, but rather soft and kindly bureaucrat, attentive and unassuming."

Molotov was criticised by Lenin and Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian ...

, with Lenin noting his "shameful bureaucratism" and stupid behaviour. On the advice of Molotov and Nikolai Bukharin

Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin (russian: Никола́й Ива́нович Буха́рин) ( – 15 March 1938) was a Bolshevik revolutionary, Soviet politician, Marxist philosopher and economist and prolific author on revolutionary theory. ...

, the Central Committee decided to reduce Lenin's work hours. In 1922, Stalin became General Secretary of the Bolshevik Party with Molotov as the ''de facto'' Second Secretary

Diplomatic rank is a system of professional and social rank used in the world of diplomacy and international relations. A diplomat's rank determines many ceremonial details, such as the order of precedence at official processions, table seating ...

. As a young follower, Molotov admired Stalin but did not refrain from criticising him. Under Stalin's patronage, Molotov became a full member of the Politburo in January 1926.

During the power struggles after

During the power struggles after Lenin's death

On 21 January 1924, at 18:50 EET, Vladimir Lenin, leader of the October Revolution and the first leader and founder of the Soviet Union, died in Gorki aged 53 after falling into a coma. The official cause of death was recorded as an incurable d ...

in 1924, Molotov remained a loyal supporter of Stalin against his various rivals: first Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian ...

, later Lev Kamenev

Lev Borisovich Kamenev. (''né'' Rozenfeld; – 25 August 1936) was a Bolshevik revolutionary and a prominent Soviet politician.

Born in Moscow to parents who were both involved in revolutionary politics, Kamenev attended Imperial Moscow Uni ...

and Grigory Zinoviev, and finally Nikolai Bukharin

Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin (russian: Никола́й Ива́нович Буха́рин) ( – 15 March 1938) was a Bolshevik revolutionary, Soviet politician, Marxist philosopher and economist and prolific author on revolutionary theory. ...

. In January 1926, he led a special commission sent to Leningrad

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

(St Petersburg) to end Zinoviev's control over the party machine in the province. In 1928, Molotov replaced Nikolai Uglanov

Nikolai Aleksandrovich Uglanov (russian: Никола́й Алекса́ндрович Угла́нов; December 5, 1886 – May 31, 1937) was a Russian Bolshevik politician and Soviet statesman who played an important role in the government of t ...

as First Secretary of the Moscow Communist Party

The First Secretary of the Moscow City Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, was the position of highest authority in the city of Moscow roughly equating to that of mayor. The position was created on November 10, 1917, following t ...

and held that position until 15 August 1929.

Personality

Trotsky and his supporters underestimated Molotov, and the same went for many others. Trotsky called him "mediocrity personified," and Molotov himself pedantically corrected comrades referring to him as "Stone Arse" by saying that Lenin had actually dubbed him "Iron Arse." However, that outward dullness concealed a sharp mind and great administrative talent. He operated mainly behind the scenes and cultivated an image of a colourless bureaucrat. Molotov was reported to be a vegetarian andteetotaler

Teetotalism is the practice or promotion of total personal abstinence from the psychoactive drug alcohol, specifically in alcoholic drinks. A person who practices (and possibly advocates) teetotalism is called a teetotaler or teetotaller, or i ...

by the American journalist John Gunther

John Gunther (August 30, 1901 – May 29, 1970) was an American journalist and writer.

His success came primarily by a series of popular sociopolitical works, known as the "Inside" books (1936–1972), including the best-selling ''Insid ...

in 1938. However, Milovan Djilas

Milovan Djilas (; , ; 12 June 1911 – 30 April 1995) was a Yugoslav communist politician, theorist and author. He was a key figure in the Partisan movement during World War II, as well as in the post-war government. A self-identified democrat ...

claimed that Molotov "drank more than Stalin"Djilas, Milovan (1962) ''Conversations with Stalin

''Conversations with Stalin'' ( sh, Razgovori sa Staljinom) is a historical memoir by Yugoslav communist and intellectual Milovan Đilas. The book is an account of Đilas's experience of several diplomatic trips to Soviet Russia as a representati ...

''. Translated by Michael B. Petrovich. Rupert Hart-Davis, Soho Square London 1962, pp. 59. and did not note his vegetarianism although they had attended several banquets.

Molotov and his wife had two daughters: Sonia, adopted in 1929, and Svetlana, born in 1930.

Soviet Premier

Addressing a Moscow communist party conference on 23 February 1929, Molotov emphasised the need to undertake "the most rapid possible growth of industry" both for economic reasons and because, he claimed, the Soviet Union was in permanent, imminent danger of attack. The argument over how fast to expand industry was behind the rift between Stalin and the right, led by Bukharin and Rykov, who feared that too rapid a pace would cause economic dislocation. With their defeat, Molotov emerged as the second most powerful figure in the Soviet Union. During the Central Committee plenum of 19 December 1930, Molotov succeeded

Addressing a Moscow communist party conference on 23 February 1929, Molotov emphasised the need to undertake "the most rapid possible growth of industry" both for economic reasons and because, he claimed, the Soviet Union was in permanent, imminent danger of attack. The argument over how fast to expand industry was behind the rift between Stalin and the right, led by Bukharin and Rykov, who feared that too rapid a pace would cause economic dislocation. With their defeat, Molotov emerged as the second most powerful figure in the Soviet Union. During the Central Committee plenum of 19 December 1930, Molotov succeeded Alexey Rykov

Alexei Ivanovich Rykov (25 February 188115 March 1938) was a Russian Bolshevik revolutionary and a Soviet politician and statesman, most prominent as premier of Russia and the Soviet Union from 1924 to 1929 and 1924 to 1930 respectively. He was ...

as the Chairman

The chairperson, also chairman, chairwoman or chair, is the presiding officer of an organized group such as a board, committee, or deliberative assembly. The person holding the office, who is typically elected or appointed by members of the grou ...

of the Council of People's Commissars

The Councils of People's Commissars (SNK; russian: Совет народных комиссаров (СНК), ''Sovet narodnykh kommissarov''), commonly known as the ''Sovnarkom'' (Совнарком), were the highest executive authorities of ...

, the equivalent of a Western head of government

The head of government is the highest or the second-highest official in the executive branch of a sovereign state, a federated state, or a self-governing colony, autonomous region, or other government who often presides over a cabinet, a gro ...

.

In that post, Molotov oversaw the implementation of the First Five-Year Plan

The first five-year plan (russian: I пятилетний план, ) of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) was a list of economic goals, created by Communist Party General Secretary Joseph Stalin, based on his policy of socialism in ...

for rapid industrialisation. Despite the great human cost, the Soviet Union under Molotov's nominal premiership made large strides in the adoption and the widespread implementation of agrarian and industrial technology. Germany secretly purchased munitions that spurred a modern armaments industry in the USSR. Ultimately, that arms industry, along with American and British aid, helped the Soviet Union prevail in the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

.

Role in collectivisation

Molotov also oversaw agricultural collectivisation under Stalin's regime. He was the main speaker at the Central Committee plenum in 10–17 November 1929, at which the decision was made to introduce collective farming in place of the thousands of small farms owned by peasants, a process that was bound to meet resistance. Molotov insisted that it must begin the following year, and warned officials to "treat thekulak

Kulak (; russian: кула́к, r=kulák, p=kʊˈlak, a=Ru-кулак.ogg; plural: кулаки́, ''kulakí'', 'fist' or 'tight-fisted'), also kurkul () or golchomag (, plural: ), was the term which was used to describe peasants who owned ove ...

as the most cunning and still undefeated enemy." In the four years that followed, millions of 'kulaks' (land-owning peasants) were forcibly moved onto special settlements to be used as slave labour. In 1931 alone almost two million were deported. In that year, Molotov told the Congress of Soviets "We have never refuted the fact that healthy prisoners capable of normal labour are used for road building and other public works. This is good for society; it is also good for the peasants themselves." The famine caused by the disruption of agricultural output and the emphasis on exporting grain to pay for industrialisation, and the harsh conditions of forced labour killed an estimated 11 million people.

Despite the famine, in September 1931, Molotov sent a secret telegram to communist leaders in the North Caucasus telling them the collection of grain for export was going "disgustingly slowly." In December, he travelled to Kharkiv

Kharkiv ( uk, wikt:Харків, Ха́рків, ), also known as Kharkov (russian: Харькoв, ), is the second-largest List of cities in Ukraine, city and List of hromadas of Ukraine, municipality in Ukraine.Lazar Kaganovich, to tell the local communists that there would be no "concessions or vacillations" in the drive to meet targets for exporting grain. This was the first of several actions that led a Kyiv Court of Appeal in 2010 to find Molotov, and Kaganovich, guilty of genocide against the Ukrainian people. On 25 July, the same two men followed up the meeting with a secret telegram ordering the Ukrainian leadership to intensify grain collection.

Molotov was succeeded in his post as premier by Stalin.

At first, Hitler rebuffed Soviet diplomatic hints that Stalin desired a treaty; but in early August 1939, Hitler allowed Foreign Minister

Molotov was succeeded in his post as premier by Stalin.

At first, Hitler rebuffed Soviet diplomatic hints that Stalin desired a treaty; but in early August 1939, Hitler allowed Foreign Minister  The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact governed Soviet–German relations until June 1941, when Hitler turned east and invaded the Soviet Union. Molotov was responsible for telling the Soviet people of the attack when he, instead of Stalin, announced the war. His speech, broadcast by radio on 22 June, characterised the Soviet Union in a role similar to that articulated by Winston Churchill in his early wartime speeches. The State Defence Committee was established soon after Molotov's speech. Stalin was elected chairman and Molotov was elected deputy chairman.

After the German invasion, Molotov conducted urgent negotiations with the British and then the Americans for wartime alliances. He took a secret flight to Scotland, where he was greeted by Eden. The risky flight in a high-altitude Tupolev TB-7 bomber flew over German-occupied Denmark and the

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact governed Soviet–German relations until June 1941, when Hitler turned east and invaded the Soviet Union. Molotov was responsible for telling the Soviet people of the attack when he, instead of Stalin, announced the war. His speech, broadcast by radio on 22 June, characterised the Soviet Union in a role similar to that articulated by Winston Churchill in his early wartime speeches. The State Defence Committee was established soon after Molotov's speech. Stalin was elected chairman and Molotov was elected deputy chairman.

After the German invasion, Molotov conducted urgent negotiations with the British and then the Americans for wartime alliances. He took a secret flight to Scotland, where he was greeted by Eden. The risky flight in a high-altitude Tupolev TB-7 bomber flew over German-occupied Denmark and the  When Beria told Stalin about the

When Beria told Stalin about the

Molotov never stopped loving his wife, and it is said he ordered his maids to make dinner for two every evening to remind him that, in his own words, "she suffered because of me." According to Erofeev, Molotov said of her: "She's not only beautiful and intelligent, the only woman minister in the Soviet Union; she's also a real

Molotov never stopped loving his wife, and it is said he ordered his maids to make dinner for two every evening to remind him that, in his own words, "she suffered because of me." According to Erofeev, Molotov said of her: "She's not only beautiful and intelligent, the only woman minister in the Soviet Union; she's also a real

Following Stalin's death, a realignment of the leadership strengthened Molotov's position.

Following Stalin's death, a realignment of the leadership strengthened Molotov's position.  In June 1956, Molotov was removed as Foreign Minister; on 29 June 1957, he was expelled from the Presidium (Politburo) after a failed attempt to remove Khrushchev as First Secretary. Although Molotov's faction initially won a vote in the Presidium 7–4 to remove Khrushchev, the latter refused to resign unless a Central Committee plenum decided so. In the plenum, which met from 22 to 29 June, Molotov and his faction were defeated. Eventually he was banished, being made ambassador to the

In June 1956, Molotov was removed as Foreign Minister; on 29 June 1957, he was expelled from the Presidium (Politburo) after a failed attempt to remove Khrushchev as First Secretary. Although Molotov's faction initially won a vote in the Presidium 7–4 to remove Khrushchev, the latter refused to resign unless a Central Committee plenum decided so. In the plenum, which met from 22 to 29 June, Molotov and his faction were defeated. Eventually he was banished, being made ambassador to the

In 1968, United Press International reported that Molotov had completed his memoirs but that they would likely never be published. The first signs of Molotov's

In 1968, United Press International reported that Molotov had completed his memoirs but that they would likely never be published. The first signs of Molotov's

''

online

* * Stephen Kotkin, Kotkin, Stephen. 2017. ''Stalin: Waiting for Hitler, 1929-1941''. New York: Random House. * * McCauley, Martin (1997). ''Who's Who in Russia since 1900''. pp. 146–147 * Miner, Steven M. "His Master's Voice: Viacheslav Mikhailovich Molotov as Stalin's Foreign Commissar." in ''The Diplomats, 1939–1979'' (Princeton University Press, 2019) pp. 65–100

online

* Roberts, Geoffrey. ''Molotov: Stalin's Cold Warrior'' (2011), 254 pp. scholarly biography. * * * * Watson, Derek. ''Molotov and Soviet Government: Sovnarkom, 1930–41'' (Palgrave Macmillan UK, 1996) * Watson, Derek. "Molotov's apprenticeship in foreign policy: The triple alliance negotiations in 1939." ''Europe-Asia Studies'' 52.4 (2000): 695–722. * Watson, Derek. "The Politburo and Foreign Policy in the 1930s." in ''The Nature of Stalin's Dictatorship'' (Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2004). 134–167

online

online

External links to books and articles

at Google Scholar

Annotated bibliography for Vyacheslav Molotov from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

''The Meaning of the Soviet-German Non-Aggression Pact'' Molotov speech to the Supreme Soviet on 31 August 1939

Reaction to German Invasion of 22 June 1941

{{DEFAULTSORT:Molotov, Vyacheslav Soviet people of World War II 1890 births 1986 deaths People from Sovetsky District, Kirov Oblast People from Yaransky Uyezd Russian Social Democratic Labour Party members Old Bolsheviks Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union members Heads of government of the Soviet Union Soviet Ministers of Foreign Affairs Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary (Soviet Union) All-Russian Central Executive Committee members Central Executive Committee of the Soviet Union members First convocation members of the Soviet of the Union Second convocation members of the Soviet of the Union Third convocation members of the Soviet of the Union Fourth convocation members of the Soviet of the Union First Secretaries of the Communist Party of Ukraine (Soviet Union) Ambassadors of the Soviet Union to Mongolia Russian atheists Russian Marxists Russian communists Anti-revisionists Joseph Stalin Great Purge perpetrators Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact Germany–Soviet Union relations Russian people of World War II World War II political leaders Honorary Members of the USSR Academy of Sciences Heroes of Socialist Labour Pravda people Recipients of the Order of Lenin Expelled members of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Soviet rehabilitations Deaths from dementia in the Soviet Union Deaths from Alzheimer's disease Burials at Novodevichy Cemetery

Temporary rift with Stalin

Between the assassination ofSergei Kirov

Sergei Mironovich Kirov (né Kostrikov; 27 March 1886 – 1 December 1934) was a Soviet politician and Bolshevik revolutionary whose assassination led to the first Great Purge.

Kirov was an early revolutionary in the Russian Empire and membe ...

, the head of the Party organisation in Leningrad

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, in December 1934, and the start of the Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Nikolay Yezhov, Yezhov'), was General ...

, there was a significant but unpublicised event rift between Stalin and Molotov. In 1936, Trotsky, in exile, noted that when lists of party leaders appeared in Soviet press reports, Molotov's name sometimes appeared as low as fourth in the list "and he was often deprived of his initials", and that when he was photographed receiving a delegation, he was never alone, but always flanked by his deputies, Janis Rudzutaks and Vlas Chubar

Vlas Yakovlevich Chubar ( uk, Влас Якович Чубар; russian: Вла́с Я́ковлевич Чуба́рь) ( – 26 February 1939) was a Ukrainian Bolshevik revolutionary and a Soviet politician. Chubar was arrested during the Great ...

. "In Soviet ritual all these are signs of paramount importance," Trotsky noted. Another startling piece of evidence was that the published transcript of the first Moscow Show Trial

The Moscow trials were a series of show trials held by the Soviet Union between 1936 and 1938 at the instigation of Joseph Stalin. They were nominally directed against "Trotskyists" and members of "Right Opposition" of the Communist Party of the ...

in August 1936, the defendants - who had been forced to confess to crimes of which they were innocent - said that they had conspired to kill Stalin and seven other leading Bolsheviks, but not Molotov. According to Alexander Orlov, an NKVD officer who defected to the west, Stalin personally crossed Molotov's name out of the original script.

In May 1936, Molotov went to the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Roma ...

on an extended holiday under careful NKVD supervision until the end of August, when Stalin apparently changed his mind and ordered Molotov's return.

Two explanations have been put forward for Molotov's temporary eclipse. On 19 March 1936 Molotov gave an interview with the editor of ''Le Temps'' concerning improved relations with Nazi Germany. Although Litvinov had made similar statements in 1934 and even visited Berlin that year, Germany had not then reoccupied the Rhineland

The Rhineland (german: Rheinland; french: Rhénanie; nl, Rijnland; ksh, Rhingland; Latinised name: ''Rhenania'') is a loosely defined area of Western Germany along the Rhine, chiefly its middle section.

Term

Historically, the Rhinelands ...

. Derek Watson believed that it was Molotov's statement on foreign policy that offended Stalin. Molotov had made it clear that improved relations with Germany could develop only if its policy changed and stated that one of the best ways for Germany to improve relations was to rejoin the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

. However, even that was not sufficient since Germany still had to give proof "of its respect for international obligations in keeping with the real interests of peace in Europe and peace generally." Robert Conquest and others believe that Molotov "dragged his feet" over Stalin's plans to purge the party and put Old Bolsheviks like Zinoviev and Kamenev on trial.

Role in the Great Purge

After his return to favour, in August, Molotov uncritically supported Stalin throughout the purge, during which, in 1938 alone, 20 out of 28 People's Commissars in Molotov's Government were executed. There is no record of Molotov attempting to moderate the course of the purges or even to save individuals, unlike some of the other Soviet officials. After his deputy, Rudzutak had been arrested, Molotov visited him in prison, and recalled years later that... "Rudzutak said he had been badly beaten and tortured. Nevertheless he held firm. Indeed, he seemed to have been cruelly tortured" ...but he did not intervene. During the Great Purge, he approved 372 documented execution lists, more than any other Soviet official, including Stalin. Molotov was one of the few with whom Stalin openly discussed the purges. When Stalin received a note denouncing the deputy chairman ofGosplan

The State Planning Committee, commonly known as Gosplan ( rus, Госплан, , ɡosˈpɫan),

was the agency responsible for central economic planning in the Soviet Union. Established in 1921 and remaining in existence until the dissolution of ...

, G.I.Lomov, he passed it to Molotov, who wrote on it: "For immediate arrest of that bastard Lomov."

Before the Bolshevik revolution, Molotov had been a "very close friend" of a Socialist Revolutionary

The Socialist Revolutionary Party, or the Party of Socialist-Revolutionaries (the SRs, , or Esers, russian: эсеры, translit=esery, label=none; russian: Партия социалистов-революционеров, ), was a major politi ...

, Alexander Arosev, who shared his exile in Vologda. In 1937, fearing arrest, Arosev tried three times to ring Molotov, who refused to speak to him. He was arrested and shot. In the 1950s, Molotov gave Arosev's daughter his signed copies of her father's books, but later wished he had kept them. "It appears that it was not so much the loss of his 'very close friend' but the loss of part of his own book collection ... that Molotov continued to regret."

Late in life, Molotov described his role in purges of the 1930s, arguing that despite the overbreadth of the purges, they were necessary to avoid Soviet defeat in World War II:

"Socialism demands immense effort. And that includes sacrifices. Mistakes were made in the process. But we could have suffered greater losses in the war -- perhaps even defeat -- if the leadership had flinched and had allowed internal disagreements, like cracks in a rock. Had leadership broken down in the 1930s we would have been in a most critical situation, many times more critical than actually turned out. I bear responsibility for this policy of repression and consider it correct. Admittedly, I have always said grave mistakes and excesses were committed, but the policy on the whole was correct."

Minister of Foreign Affairs

In 1939,Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

's invasion of the rest of Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

, in violation of the 1938 Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Nazi Germany, Germany, the United Kingdom, French Third Republic, France, and Fa ...

, made Stalin believe that Britain and France, which had signed the agreement, would not be reliable allies against German expansion. That made him decide instead to seek to conciliate Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

. In May 1939, Maxim Litvinov

Maxim Maximovich Litvinov (; born Meir Henoch Wallach; 17 July 1876 – 31 December 1951) was a Russian revolutionary and prominent Soviet statesman and diplomat.

A strong advocate of diplomatic agreements leading towards disarmament, Litvinov wa ...

, the Jewish Commissar for Foreign Affairs, was dismissed; Molotov was appointed to succeed him.

Relations between Molotov and Litvinov had been bad. Maurice Hindus in 1954 stated in his book ''Crisis in the Kremlin'':

It is well known in Moscow that Molotov always detested Litvinov. Molotov's detestation for Litvinov was purely of a personal nature. No Moscovite I have ever known, whether a friend of Molotov or of Litvinov, has ever taken exception to this view. Molotov was always resentful of Litvinov's fluency in French, German and English, as he was distrustful of Litvinov's easy manner with foreigners. Never having lived abroad, Molotov always suspected that there was something impure and sinful in Litvinov's broad-mindedness and appreciation of Western civilisation.Litvinov had no respect for Molotov, regarding him as a small-minded intriguer and accomplice in terror.

Molotov was succeeded in his post as premier by Stalin.

At first, Hitler rebuffed Soviet diplomatic hints that Stalin desired a treaty; but in early August 1939, Hitler allowed Foreign Minister

Molotov was succeeded in his post as premier by Stalin.

At first, Hitler rebuffed Soviet diplomatic hints that Stalin desired a treaty; but in early August 1939, Hitler allowed Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop

Ulrich Friedrich Wilhelm Joachim von Ribbentrop (; 30 April 1893 – 16 October 1946) was a German politician and diplomat who served as Minister of Foreign Affairs of Nazi Germany from 1938 to 1945.

Ribbentrop first came to Adolf Hitler's not ...

to begin serious negotiations. A trade agreement was concluded on 18 August, and on 22 August Ribbentrop flew to Moscow to conclude a formal non-aggression treaty. Although the treaty is known as the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was a non-aggression pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union that enabled those powers to partition Poland between them. The pact was signed in Moscow on 23 August 1939 by German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ri ...

, it was Stalin and Hitler, not Molotov and Ribbentrop, who decided the content of the treaty.

The most important part of the agreement was the secret protocol, which provided for the partition of Poland, Finland and the Baltic States

The Baltic states, et, Balti riigid or the Baltic countries is a geopolitical term, which currently is used to group three countries: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. All three countries are members of NATO, the European Union, the Eurozone, ...

between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union and for the Soviet annexation of Bessarabia

Bessarabia (; Gagauz: ''Besarabiya''; Romanian: ''Basarabia''; Ukrainian: ''Бессара́бія'') is a historical region in Eastern Europe, bounded by the Dniester river on the east and the Prut river on the west. About two thirds of Be ...

(then part of Romania, now Moldova

Moldova ( , ; ), officially the Republic of Moldova ( ro, Republica Moldova), is a Landlocked country, landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by Romania to the west and Ukraine to the north, east, and south. The List of states ...

). The protocol gave Hitler the green light for his invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week aft ...

, which began on 1 September.

The pact's terms gave Hitler authorisation to occupy two thirds of Western Poland

Poland ( pl, Polska) is a country that extends across the North European Plain from the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south to the sandy beaches of the Baltic Sea in the north. Poland is the fifth-most populous country of the Europe ...

and the whole of Lithuania

Lithuania (; lt, Lietuva ), officially the Republic of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos Respublika, links=no ), is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. Lithuania ...

. Molotov was given a free hand in relation to Finland. In the Winter War

The Winter War,, sv, Vinterkriget, rus, Зи́мняя война́, r=Zimnyaya voyna. The names Soviet–Finnish War 1939–1940 (russian: link=no, Сове́тско-финская война́ 1939–1940) and Soviet–Finland War 1 ...

, a combination of fierce Finnish resistance and Soviet mismanagement resulted in Finland losing much of its territory but not its independence. The pact was later amended to allocate Lithuania to the Soviets in exchange for a more favourable border in Poland for Germany. The annexations led to horrific suffering and loss of life in the countries occupied and partitioned by both dictatorships. On 5 March 1940, Lavrentiy Beria

Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria (; rus, Лавре́нтий Па́влович Бе́рия, Lavréntiy Pávlovich Bériya, p=ˈbʲerʲiə; ka, ლავრენტი ბერია, tr, ; – 23 December 1953) was a Georgian Bolsheviks ...

gave Molotov, along with Anastas Mikoyan, Kliment Voroshilov

Kliment Yefremovich Voroshilov (, uk, Климент Охрімович Ворошилов, ''Klyment Okhrimovyč Vorošylov''), popularly known as Klim Voroshilov (russian: link=no, Клим Вороши́лов, ''Klim Vorošilov''; 4 Februa ...

and Stalin, a note proposing the execution of 25,700 Polish anti-Soviet

Anti-Sovietism, anti-Soviet sentiment, called by Soviet authorities ''antisovetchina'' (russian: антисоветчина), refers to persons and activities actually or allegedly aimed against the Soviet Union or government power within the ...

officers in what has become known as the Katyn massacre

The Katyn massacre, "Katyń crime"; russian: link=yes, Катынская резня ''Katynskaya reznya'', "Katyn massacre", or russian: link=no, Катынский расстрел, ''Katynsky rasstrel'', "Katyn execution" was a series of m ...

.

In November 1940, Stalin sent Molotov to Berlin to meet Ribbentrop and Hitler. In January 1941, British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden

Robert Anthony Eden, 1st Earl of Avon, (12 June 1897 – 14 January 1977) was a British Conservative Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1955 until his resignation in 1957.

Achieving rapid promo ...

visited Turkey in an attempt to get the Turks to enter the war on the Allies' side. The purpose of Eden's visit was anti-German, rather than anti-Soviet, but Molotov assumed otherwise. In a series of conversations with Italian Ambassador Augusto Rosso, Molotov claimed that the Soviets would soon be faced with an Anglo–Turkish invasion of the Crimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a pop ...

. The British historian D.C. Watt argued that on the basis of Molotov's statements to Rosso, it would appear that, in early 1941, Stalin and Molotov viewed Britain, rather than Germany, as the principal threat.

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact governed Soviet–German relations until June 1941, when Hitler turned east and invaded the Soviet Union. Molotov was responsible for telling the Soviet people of the attack when he, instead of Stalin, announced the war. His speech, broadcast by radio on 22 June, characterised the Soviet Union in a role similar to that articulated by Winston Churchill in his early wartime speeches. The State Defence Committee was established soon after Molotov's speech. Stalin was elected chairman and Molotov was elected deputy chairman.

After the German invasion, Molotov conducted urgent negotiations with the British and then the Americans for wartime alliances. He took a secret flight to Scotland, where he was greeted by Eden. The risky flight in a high-altitude Tupolev TB-7 bomber flew over German-occupied Denmark and the

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact governed Soviet–German relations until June 1941, when Hitler turned east and invaded the Soviet Union. Molotov was responsible for telling the Soviet people of the attack when he, instead of Stalin, announced the war. His speech, broadcast by radio on 22 June, characterised the Soviet Union in a role similar to that articulated by Winston Churchill in his early wartime speeches. The State Defence Committee was established soon after Molotov's speech. Stalin was elected chairman and Molotov was elected deputy chairman.

After the German invasion, Molotov conducted urgent negotiations with the British and then the Americans for wartime alliances. He took a secret flight to Scotland, where he was greeted by Eden. The risky flight in a high-altitude Tupolev TB-7 bomber flew over German-occupied Denmark and the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian S ...

. From there, he took a train to London to discuss the possibility of opening a second front against Germany.

After signing the Anglo–Soviet Treaty of 1942

The Anglo-Soviet Treaty, formally the Twenty-Year Mutual Assistance Agreement Between the United Kingdom and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, established a military and political alliance between the Soviet Union and the British Empire.

...

on 26 May, Molotov left for Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

. Molotov met US President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

and agreed on a lend-lease

Lend-Lease, formally the Lend-Lease Act and introduced as An Act to Promote the Defense of the United States (), was a policy under which the United States supplied the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union and other Allied nations with food, oil, ...

plan. Both the British and the Americans only vaguely promised to open a second front against Germany. On his flight back to the Soviet Union, his plane was attacked by German fighters and later mistakenly by Soviet fighters.

There is no evidence that Molotov ever persuaded Stalin to pursue a different policy from that on which he had already decided. Volkogonov could not find one case where any of the elite in government openly disagreed with Stalin.

There is some evidence that, although Stalin realised he needed Molotov, Stalin did not like him. Stalin's one-time bodyguard, Amba,stated: "More general dislike for this statesman robot and for his position in the Kremlin could scarcely be wished and it was apparent that Stalin himself joined in this feeling". Amba asked the question: "What then has made Stalin collaborate so closely with him? There are many more talented people in the Soviet Union and Stalin no doubt had the means to find them. Is he afraid of close collaboration with a more human and sympathetic assistant?"At a jolly party, Amba recalled an incident whereby Poskryobyshev approached Stalin and whispered in his ear. Stalin replied, "Does it have to be right away?" Everybody realised at once that the conversation was regarding Molotov. In half an hour, Stalin was informed of Molotov's arrival. Although the whispered conversation between Molotov and Stalin only lasted five minutes, the merriment of the gathering evaporated as everybody talked in hushed tones. Amba stated, "Then the blanket left. Instantly the gaiety returned". Vareykis said that "a gentle angel has flown past": a Russian expression for when a sudden silence descends. Breaking the tension, Laurentyev quipped in a harsh Georgian accent, "Go, friendly soul". Out of those in attendance, Stalin laughed the loudest at Laurentyev's joke. Stalin could be rude to Molotov. In 1942, Stalin took Molotov to task for his handling of the negotiations with the Allies. He cabled Molotov on 3 June:

" amdissatisfied with the terseness and reticence of all your communications. You convey to us from your talks with Roosevelt and Churchill only what you yourself consider is important, and omit all the rest. Meanwhile, the instancetalin Talin may refer to: Places * Talin, Armenia, a city * Tálín, a municipality and village in the Czech Republic *Tallinn, capital of Estonia * Talin, Iran, a village in West Azerbaijan Province *Talin, Syria, a village in Tartus Governorate Other ...would like to know everything. What you consider important and what you think unimportant. This refers to the draft of the communiqué as well. You have not informed us whose draft it is, whether it has been agreed with the British in full and why, after all, there could not be two communiqués, one concerning the talks in Britain and one concerning the talks in the USA. We are having to guess because of your reticence. We further consider it expedient that both communiqués should mention among other things the creation of a second front in Europe and that full understanding has been reached in this matter. We also consider that it is absolutely necessary both communiqués should mention the supply of war materials to the Soviet Union from Britain and the USA. In all the rest we agree with the contents of the draft communiqué you sent us".

When Beria told Stalin about the

When Beria told Stalin about the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

and its importance, Stalin handpicked Molotov to be the man in charge of the Soviet atomic bomb project

The Soviet atomic bomb project was the classified research and development program that was authorized by Joseph Stalin in the Soviet Union to develop nuclear weapons during and after World War II.

Although the Soviet scientific community disc ...

. However, under Molotov's leadership, the bomb and the project itself developed very slowly, and he was replaced by Beria in 1944 on the advice of Igor Kurchatov

Igor Vasil'evich Kurchatov (russian: Игорь Васильевич Курчатов; 12 January 1903 – 7 February 1960), was a Soviet physicist who played a central role in organizing and directing the former Soviet program of nuclear weapo ...

. When Roosevelt's successor as U.S. President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

told Stalin that the Americans had created a bomb never seen before, Stalin relayed the conversation to Molotov and told him to speed up development. On Stalin's orders, the Soviet government substantially increased investment in the project. In a collaboration with Kliment Voroshilov

Kliment Yefremovich Voroshilov (, uk, Климент Охрімович Ворошилов, ''Klyment Okhrimovyč Vorošylov''), popularly known as Klim Voroshilov (russian: link=no, Клим Вороши́лов, ''Klim Vorošilov''; 4 Februa ...

, Molotov contributed both musically and lyrically to the 1944 version of the Soviet national anthem

The "State Anthem of the Soviet Union" was the national anthem of the Soviet Union and the regional anthem of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic from 1944 to 1991, replacing "The Internationale". Its original lyrics were written b ...

. Molotov asked the writers to include a line or two about peace. The role of Molotov and Voroshilov in the making of the new Soviet anthem was, in the words of the historian Simon Sebag-Montefiore

Simon Jonathan Sebag Montefiore (; born 27 June 1965) is a British historian, television presenter and author of popular history books and novels,

including ''Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar' (2003), Monsters: History's Most Evil Men and ...

, acting as music judges for Stalin.

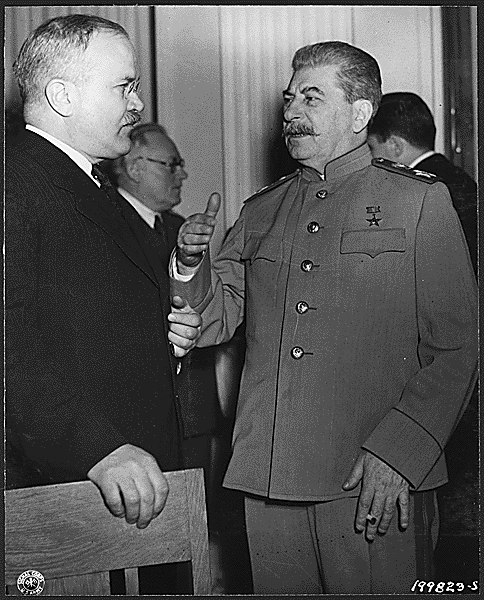

Molotov accompanied Stalin to the Teheran Conference

The Tehran Conference ( codenamed Eureka) was a strategy meeting of Joseph Stalin, Franklin Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill from 28 November to 1 December 1943, after the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran. It was held in the Soviet Union's embassy ...

in 1943, the Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference (codenamed Argonaut), also known as the Crimea Conference, held 4–11 February 1945, was the World War II meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union to discuss the post ...

in 1945, and, after the defeat of Germany, the Potsdam Conference

The Potsdam Conference (german: Potsdamer Konferenz) was held at Potsdam in the Soviet occupation zone from July 17 to August 2, 1945, to allow the three leading Allies to plan the postwar peace, while avoiding the mistakes of the Paris Pe ...

. He represented the Soviet Union at the San Francisco Conference

The United Nations Conference on International Organization (UNCIO), commonly known as the San Francisco Conference, was a convention of delegates from 50 Allied nations that took place from 25 April 1945 to 26 June 1945 in San Francisco, Calif ...

, which created the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

. Even during the wartime alliance, Molotov was known as a tough negotiator and a determined defender of Soviet interests. Molotov lost his position of First Deputy chairman on 19 March 1946, after the Council of People's Commissars had been reformed as the Council of Ministers.

From 1945 to 1947, Molotov took part in all four conferences of foreign ministers

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between co ...

of the victorious states in the Second World War. In general, he was distinguished by an unco-operative attitude towards the Western powers. Molotov, at the direction of the Soviet government, condemned the Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred over $13 billion (equivalent of about $ in ) in economic re ...

as imperialistic and claimed it was dividing Europe into two camps: one capitalist and the other communist. In response, the Soviet Union, along with the other Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

nations, initiated what is known as the Molotov Plan

The Molotov Plan was the system created by the Soviet Union in 1947 in order to provide aid to rebuild the countries in Eastern Europe that were politically and economically aligned to the Soviet Union (aka satellite state). It was originally calle ...

. The plan created several bilateral relations

Bilateralism is the conduct of political, economic, or cultural relations between two sovereign states. It is in contrast to unilateralism or multilateralism, which is activity by a single state or jointly by multiple states, respectively. When ...

between the states of Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union and later evolved into the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance

The Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (, ; English abbreviation COMECON, CMEA, CEMA, or CAME) was an economic organization from 1949 to 1991 under the leadership of the Soviet Union that comprised the countries of the Eastern Bloc along wit ...

(CMEA).

In the postwar period, Molotov's power began to decline. A clear sign of his precarious position was his inability to prevent the arrest for "treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

" in December 1948 of his Jewish wife, Polina Zhemchuzhina

Polina Semyonovna Zhemchuzhina (born Perl Solomonovna Karpovskaya; 27 February 1897 – 1 April 1970) was a Soviet politician and the wife of the Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov. Zhemchuzhina was the director of the Soviet national ...

, whom Stalin had long distrusted. Molotov initially protested the persecution against her by abstaining from the vote to condemn her, but later recanted, stating: "I acknowledge my heavy sense of remorse for not having prevented Zhemchuzhina, a person very dear to me, from making her mistakes and from forming ties with anti-Soviet Jewish nationalists .. and divorced Zhemchuzhina.

Polina Zhemchuzhina befriended Golda Meir

Golda Meir, ; ar, جولدا مائير, Jūldā Māʾīr., group=nb (born Golda Mabovitch; 3 May 1898 – 8 December 1978) was an Israeli politician, teacher, and ''kibbutznikit'' who served as the fourth prime minister of Israel from 1969 to 1 ...

, who arrived in Moscow in November 1948 as the first Israeli envoy to the Soviet Union. There are unsubstantiated claims that, being fluent in Yiddish

Yiddish (, or , ''yidish'' or ''idish'', , ; , ''Yidish-Taytsh'', ) is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated during the 9th century in Central Europe, providing the nascent Ashkenazi community with a ver ...

, Zhemchuzhina acted as a translator for a diplomatic meeting between Meir and her husband, the Soviet foreign minister. However, this claim (of being an interpreter) is not supported by Meir's memoir ''My Life My Life may refer to:

Autobiographies

* ''Mein Leben'' (Wagner) (''My Life''), by Richard Wagner, 1870

* ''My Life'' (Clinton autobiography), by Bill Clinton, 2004

* ''My Life'' (Meir autobiography), by Golda Meir, 1973

* ''My Life'' (Mosley a ...

''. Presentation of her ambassadorial credentials was done in Hebrew, not in Yiddish. According to Meir's own account of the reception given by Molotov on 7 November, "Mrs. Zhemchuzhina has spent significant time during this reception not only talking to Golda Meir herself but also in conversation with Mrs. Meir's daughter Sarah and her friend Yael Namir about their life as kibbutzniks. They have discussed the complete collectivization of property and related issues. At the end Mrs. Zhemchuzhina gave Golda Meir's daughter Sarah a hug and said: 'Be well. If everything goes well with you, it will go well for all Jews everywhere.' "

Zhemchuzhina was imprisoned for a year in the Lubyanka and was then exiled for three years in an obscure Russian city. She was sentenced to hard labour, spending five years in exile in Kazakhstan. Molotov had no communication with her except for the scant news that he received from Beria, whom he loathed. Zhemchuzhina was freed immediately after the death of Stalin.

In 1949, Molotov was replaced as Foreign Minister by Andrey Vyshinsky

Andrey Yanuaryevich Vyshinsky (russian: Андре́й Януа́рьевич Выши́нский; pl, Andrzej Wyszyński) ( – 22 November 1954) was a Soviet politician, jurist and diplomat.

He is known as a state prosecutor of Joseph ...

but retained his position as First Deputy Premier and membership in the Politburo. Being appointed Foreign Minister by Stalin to replace the Jewish predecessor Maxim Litvinov

Maxim Maximovich Litvinov (; born Meir Henoch Wallach; 17 July 1876 – 31 December 1951) was a Russian revolutionary and prominent Soviet statesman and diplomat.

A strong advocate of diplomatic agreements leading towards disarmament, Litvinov wa ...

to facilitate negotiations with Nazi Germany, Molotov was thus also dismissed from the same position at least in part because his wife was also of Jewish origin.

Molotov never stopped loving his wife, and it is said he ordered his maids to make dinner for two every evening to remind him that, in his own words, "she suffered because of me." According to Erofeev, Molotov said of her: "She's not only beautiful and intelligent, the only woman minister in the Soviet Union; she's also a real

Molotov never stopped loving his wife, and it is said he ordered his maids to make dinner for two every evening to remind him that, in his own words, "she suffered because of me." According to Erofeev, Molotov said of her: "She's not only beautiful and intelligent, the only woman minister in the Soviet Union; she's also a real Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

, a real Soviet person." According to Stalin's daughter, Molotov became very subservient to his wife. Molotov was a yes-man to his wife just as he was to Stalin.

Postwar career

At the 19th Party Congress in 1952, Molotov was elected to the replacement for the Politburo, thePresidium

A presidium or praesidium is a council of executive officers in some political assemblies that collectively administers its business, either alongside an individual president or in place of one.

Communist states

In Communist states the presidi ...

, but was not listed among the members of the newly established secret body known as the Bureau of the Presidium, which indicated that he had fallen out of Stalin's favour. At the 19th Congress, Stalin said,

"There has been criticism of comrade Molotov and Mikoyan

Russian Aircraft Corporation "MiG" (russian: Российская самолётостроительная корпорация „МиГ“, Rossiyskaya samolyotostroitel'naya korporatsiya "MiG"), commonly known as Mikoyan and MiG, was a Russi ...

by the Central Committee," mistakes including the publication of a wartime speech by Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

favourable to the Soviet Union's wartime efforts. Both Molotov and Mikoyan were falling out of favour rapidly, with Stalin telling Beria, Khrushchev, Malenkov and Nikolai Bulganin

Nikolai Alexandrovich Bulganin (russian: Никола́й Алекса́ндрович Булга́нин; – 24 February 1975) was a Soviet politician who served as Minister of Defense (1953–1955) and Premier of the Soviet Union (1955–19 ...

that he no longer wanted to see Molotov and Mikoyan around. At his 73rd birthday, Stalin treated both with disgust. In his speech to the 20th Party Congress in 1956, Khrushchev told delegates that Stalin had plans for "finishing off" Molotov and Mikoyan in the aftermath of the 19th Congress.

Following Stalin's death, a realignment of the leadership strengthened Molotov's position.

Following Stalin's death, a realignment of the leadership strengthened Molotov's position. Georgy Malenkov

Georgy Maximilianovich Malenkov ( – 14 January 1988) was a Soviet politician who briefly succeeded Joseph Stalin as the leader of the Soviet Union. However, at the insistence of the rest of the Presidium, he relinquished control over the p ...

, Stalin's successor in the post of General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, reappointed Molotov as Minister of Foreign Affairs on 5 March 1953. Although Molotov was seen as a likely successor to Stalin in the immediate aftermath of his death, he never sought to become leader of the Soviet Union. A Troika

Troika or troyka (from Russian тройка, meaning 'a set of three') may refer to:

Cultural tradition

* Troika (driving), a traditional Russian harness driving combination, a cultural icon of Russia

* Troika (dance), a Russian folk dance

Pol ...

was established immediately after Stalin's death, consisting of Malenkov, Beria, and Molotov, but ended when Malenkov and Molotov deceived Beria. Molotov supported the removal and later the execution of Beria on the orders of Khrushchev. The new Party Secretary, Khrushchev, soon emerged as the new leader of the Soviet Union

During its 69-year history, the Soviet Union usually had a ''de facto'' leader who would not necessarily be head of state but would lead while holding an office such as premier or general secretary. Under the 1977 Constitution, the chairman of ...

. He presided over a gradual domestic liberalisation and a thaw in foreign policy, as was manifest in a reconciliation with Josip Broz Tito

Josip Broz ( sh-Cyrl, Јосип Броз, ; 7 May 1892 – 4 May 1980), commonly known as Tito (; sh-Cyrl, Тито, links=no, ), was a Yugoslav communist revolutionary and statesman, serving in various positions from 1943 until his deat ...

's government in Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label=Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavija ...

, which Stalin had expelled from the communist movement. Molotov, an old-guard Stalinist, seemed increasingly out of place in the new environment, but represented the Soviet Union at the Geneva Conference of 1955.

Molotov's position became increasingly tenuous after February 1956, when Khrushchev launched an unexpected denunciation of Stalin at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party. Khrushchev attacked Stalin over the purges of the 1930s and the defeats of the early years of the Second World War, which he blamed on Stalin's overly-trusting attitude towards Hitler and the purges of the Red Army command structure. Molotov was the most senior of Stalin's collaborators still in government and had played a leading role in the purges, so it became evident that Khrushchev's examination of the past would probably result in the fall from power of Molotov, who became the leader of an old-guard faction that sought to overthrow Khrushchev.

In June 1956, Molotov was removed as Foreign Minister; on 29 June 1957, he was expelled from the Presidium (Politburo) after a failed attempt to remove Khrushchev as First Secretary. Although Molotov's faction initially won a vote in the Presidium 7–4 to remove Khrushchev, the latter refused to resign unless a Central Committee plenum decided so. In the plenum, which met from 22 to 29 June, Molotov and his faction were defeated. Eventually he was banished, being made ambassador to the

In June 1956, Molotov was removed as Foreign Minister; on 29 June 1957, he was expelled from the Presidium (Politburo) after a failed attempt to remove Khrushchev as First Secretary. Although Molotov's faction initially won a vote in the Presidium 7–4 to remove Khrushchev, the latter refused to resign unless a Central Committee plenum decided so. In the plenum, which met from 22 to 29 June, Molotov and his faction were defeated. Eventually he was banished, being made ambassador to the Mongolian People's Republic

The Mongolian People's Republic ( mn, Бүгд Найрамдах Монгол Ард Улс, БНМАУ; , ''BNMAU''; ) was a socialist state which existed from 1924 to 1992, located in the historical region of Outer Mongolia in East Asia. It w ...

. Molotov and his associates were denounced as "the Anti-Party Group

The Anti-Party Group ( rus, Антипартийная группа, r=Antipartiynaya gruppa) was a Stalinist group within the leadership of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union that unsuccessfully attempted to depose Nikita Khrushchev as Fi ...

" but notably were not subject to such unpleasant repercussions that had been customary for denounced officials in the Stalin years. In 1960, he was appointed Soviet representative to the International Atomic Energy Agency

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) is an intergovernmental organization that seeks to promote the peaceful use of nuclear energy and to inhibit its use for any military purpose, including nuclear weapons. It was established in 1957 ...

, which was seen as a partial rehabilitation. However, after the 22nd Party Congress in 1961, during which Khrushchev carried out his de-Stalinisation

De-Stalinization (russian: десталинизация, translit=destalinizatsiya) comprised a series of political reforms in the Soviet Union after the death of long-time leader Joseph Stalin in 1953, and the thaw brought about by ascension ...

campaign, including the removal of Stalin's body from Lenin's Mausoleum

Lenin's Mausoleum (from 1953 to 1961 Lenin's & Stalin's Mausoleum) ( rus, links=no, Мавзолей Ленина, r=Mavzoley Lenina, p=məvzɐˈlʲej ˈlʲenʲɪnə), also known as Lenin's Tomb, situated on Red Square in the centre of Moscow, i ...

, Molotov, along with Lazar Kaganovich, was removed from all positions and expelled from the Communist Party. In 1962, all of Molotov's party documents and files were destroyed by the authorities.

In retirement, Molotov remained unrepentant about his role under Stalin's rule. He suffered a heart attack in January 1962. After the Sino-Soviet split