Vivien Thomas on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Vivien Theodore Thomas (August 29, 1910 – November 26, 1985) was an American laboratory supervisor who developed a procedure used to treat blue baby syndrome (now known as cyanotic heart disease) in the 1940s. He was the assistant to surgeon

In 1943, while pursuing his shock research, Blalock was approached by

In 1943, while pursuing his shock research, Blalock was approached by

News of this groundbreaking story was circulated around the world by the

News of this groundbreaking story was circulated around the world by the

Partners of the Heart.

''

Blue Baby Operation Exhibit

{{DEFAULTSORT:Thomas, Vivien American cardiac surgeons Johns Hopkins University faculty Johns Hopkins Hospital physicians 1910 births 1985 deaths People from New Iberia, Louisiana Deaths from pancreatic cancer African-American inventors African-American physicians African-American scientists American scientists Janitors 20th-century surgeons 20th-century African-American people

Alfred Blalock

Alfred Blalock (April 5, 1899 – September 15, 1964) was an American surgeon most noted for his work on the medical condition of shock as well as Tetralogy of Fallot— commonly known as Blue baby syndrome. He created, with assistance from h ...

in Blalock's experimental animal laboratory at Vanderbilt University

Vanderbilt University (informally Vandy or VU) is a private research university in Nashville, Tennessee. Founded in 1873, it was named in honor of shipping and rail magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt, who provided the school its initial $1-million ...

in Nashville, Tennessee

Nashville is the capital city of the U.S. state of Tennessee and the seat of Davidson County. With a population of 689,447 at the 2020 U.S. census, Nashville is the most populous city in the state, 21st most-populous city in the U.S., and ...

, and later at the Johns Hopkins University

Johns Hopkins University (Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private research university in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1876, Johns Hopkins is the oldest research university in the United States and in the western hemisphere. It consi ...

in Baltimore, Maryland

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore wa ...

. Thomas was unique in that he did not have any professional education or experience in a research laboratory; however, he served as supervisor of the surgical laboratories at Johns Hopkins for 35 years. In 1976, Hopkins awarded him an honorary doctorate and named him an instructor of surgery for the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine

The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine (JHUSOM) is the medical school of Johns Hopkins University, a private research university in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1893, the School of Medicine shares a campus with the Johns Hopkins Hospi ...

. Without any education past high school, Thomas rose above poverty and racism to become a cardiac surgery

Cardiac surgery, or cardiovascular surgery, is surgery on the heart or great vessels performed by cardiac surgeons. It is often used to treat complications of ischemic heart disease (for example, with coronary artery bypass grafting); to co ...

pioneer and a teacher of operative techniques to many of the country's most prominent surgeons.

A PBS documentary, ''Partners of the Heart'', was broadcast in 2003 on PBS's ''American Experience

''American Experience'' is a television program airing on the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) in the United States. The program airs documentaries, many of which have won awards, about important or interesting events and people in American his ...

''. In the 2004 HBO movie ''Something the Lord Made

''Something the Lord Made'' is a 2004 American made-for-television biographical drama film about the black cardiac pioneer Vivien Thomas (1910–1985) and his complex and volatile partnership with white surgeon Alfred Blalock (1899–1964), th ...

'', based on Katie McCabe's National Magazine Award

The National Magazine Awards, also known as the Ellie Awards, honor print and digital publications that consistently demonstrate superior execution of editorial objectives, innovative techniques, noteworthy enterprise and imaginative design. Or ...

–winning '' Washingtonian'' article of the same title, Vivien Thomas was portrayed by Mos Def

Yasiin Bey (; born Dante Terrell Smith, December 11, 1973), previously and more commonly known by his stage name Mos Def (), is an American rapper, singer, songwriter, and actor. His hip hop career began in 1994, alongside his siblings in the s ...

.

Background

Thomas was born in small-townLouisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is bord ...

during the Jim Crow

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sou ...

era, but sources disagree in which small town. Most sources say he was born to Willard Maceo Thomas and the former Mary Alice Eaton in New Iberia, Louisiana

New Iberia (french: La Nouvelle-Ibérie; es, Nueva Iberia) is the largest city in and parish seat of Iberia Parish in the U.S. state of Louisiana. The city of New Iberia is located approximately southeast of Lafayette, and forms part of the L ...

in 1910. He listed New Iberia as his birthplace on his World War II draft card, and when he died in 1985, his obituary in ''The Baltimore Sun'' also listed New Iberia. But in his autobiography, published shortly after his death, Thomas writes that he was born in Lake Providence, Louisiana

Lake Providence is a town in, and the parish seat of, East Carroll Parish in northeastern Louisiana. The population was 5,104 at the 2000 census and declined by 21.8 percent to 3,991 in 2010. The town's poverty rate is approximately 55 percent; ...

. New Iberia was his mother's hometown, Lake Providence his father's. Either way, the family did not stay in Louisiana for long, moving to Nashville, Tennessee

Nashville is the capital city of the U.S. state of Tennessee and the seat of Davidson County. With a population of 689,447 at the 2020 U.S. census, Nashville is the most populous city in the state, 21st most-populous city in the U.S., and ...

when Thomas was about two years old.

Thomas attended Pearl High School in Nashville in the 1920s, and graduated in 1929. Thomas' father was a carpenter, and took pleasure in passing down his expertise to his sons. Thomas worked with his father and brothers every day after school and on Saturdays, doing jobs such as measuring, sawing, and nailing. This experience proved beneficial to Thomas, as he was able to secure a carpentry job at Fisk University

Fisk University is a private historically black liberal arts college in Nashville, Tennessee. It was founded in 1866 and its campus is a historic district listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

In 1930, Fisk was the first Africa ...

repairing facility damages after graduating from high school. Thomas had hoped to attend college and become a doctor, but the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

derailed his plans. Thomas intended to work hard, save money, and gain a higher education as soon as he could afford it. Determined to broaden his skill set, in 1930 he reached out to childhood friend Charles Manlove (who was working at Vanderbilt University at the time) to ask if there were any jobs available.

Career

In the wake of the stock market crash in October 1929, Thomas put his educational plans on hold and, through a friend, in February 1930 secured a job as surgical research assistant with Dr.Alfred Blalock

Alfred Blalock (April 5, 1899 – September 15, 1964) was an American surgeon most noted for his work on the medical condition of shock as well as Tetralogy of Fallot— commonly known as Blue baby syndrome. He created, with assistance from h ...

at Vanderbilt University

Vanderbilt University (informally Vandy or VU) is a private research university in Nashville, Tennessee. Founded in 1873, it was named in honor of shipping and rail magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt, who provided the school its initial $1-million ...

. On his first day of work, Thomas assisted Blalock with a surgical experiment on a dog. At the end of Thomas's first day, Blalock told Thomas they would do another experiment the next morning. Blalock told Thomas to "come in and put the animal to sleep and get it set up." Within a few weeks, Thomas was starting surgery on his own. Thomas was classified and paid as a janitor

A janitor (American English, Scottish English), also known as a custodian, porter, cleanser, cleaner or caretaker, is a person who cleans and maintains buildings. In some cases, they will also carry out maintenance and security duties. A simil ...

, despite the fact that by the mid-1930s, he was doing the work of a postdoctoral researcher

A postdoctoral fellow, postdoctoral researcher, or simply postdoc, is a person professionally conducting research after the completion of their doctoral studies (typically a PhD). The ultimate goal of a postdoctoral research position is to pu ...

in the lab.

Thomas struggled with finances despite saving most of what he earned. The salaries that he received did not provide enough comfort to quit his laboratory research job and go back to school. Nashville's banks failed nine months after Thomas started his job with Blalock, and his savings were wiped out. He abandoned his plans for college and medical school, relieved to have even a low-paying job as the Great Depression deepened. Vivien Thomas continued his work with Dr. Blalock, and saving his earnings, so that he could provide for his daughters and wife the best he could.

Working with Blalock

Vanderbilt

Thomas and Blalock did groundbreaking research into the causes of hemorrhagic and traumaticshock

Shock may refer to:

Common uses Collective noun

*Shock, a historic commercial term for a group of 60, see English numerals#Special names

* Stook, or shock of grain, stacked sheaves

Healthcare

* Shock (circulatory), circulatory medical emerge ...

. This work later evolved into research on crush syndrome

Crush syndrome (also traumatic rhabdomyolysis or Bywaters' syndrome) is a medical condition characterized by major shock and kidney failure after a crushing injury to skeletal muscle. Crush ''injury'' is compression of the arms, legs, or other p ...

and saved the lives of thousands of soldiers on the battlefields of World War II. In hundreds of experiments, the two disproved traditional theories which held that shock was caused by toxins

A toxin is a naturally occurring organic poison produced by metabolic activities of living cells or organisms. Toxins occur especially as a protein or conjugated protein. The term toxin was first used by organic chemist Ludwig Brieger (1849� ...

in the blood. Blalock, a highly original scientific thinker and something of an iconoclast, had theorized that shock resulted from fluid loss outside the vascular bed and that the condition could be effectively treated by fluid replacement. Assisted by Thomas, he was able to provide incontrovertible proof of this theory, and in so doing, he gained wide recognition in the medical community by the mid-1930s. At this same time, Blalock and Thomas began experimental work in vascular and cardiac surgery

Cardiac surgery, or cardiovascular surgery, is surgery on the heart or great vessels performed by cardiac surgeons. It is often used to treat complications of ischemic heart disease (for example, with coronary artery bypass grafting); to co ...

, defying medical taboos against operating upon the heart. It was this work that laid the foundation for the revolutionary life saving surgery they were to perform at Johns Hopkins

Johns Hopkins (May 19, 1795 – December 24, 1873) was an American merchant, investor, and philanthropist. Born on a plantation, he left his home to start a career at the age of 17, and settled in Baltimore, Maryland where he remained for most ...

a decade later. Vivien Thomas spent 11 years at Vanderbilt with Blalock before moving to Johns Hopkins.

Johns Hopkins

By 1940, the work Blalock had done with Thomas placed Blalock at the forefront of American surgery, and when he was offered the position of Chief of Surgery at his alma mater Johns Hopkins in 1941, he requested that Thomas accompany him. Thomas arrived inBaltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore was ...

with his family in June of that year, confronting a severe housing shortage and a level of racism worse than they had endured in Nashville

Nashville is the capital city of the U.S. state of Tennessee and the seat of Davidson County. With a population of 689,447 at the 2020 U.S. census, Nashville is the most populous city in the state, 21st most-populous city in the U.S., and th ...

. Hopkins, like the rest of Baltimore, was rigidly segregated, and the only Black employees at the institution were janitors. When Thomas walked the halls in his white lab coat, many heads turned. He began changing into his city clothes when he walked from the laboratory to Blalock's office because he received so much attention. During this time, he lived in the 1200 block of Caroline Street in the community now known as Oliver, Baltimore

Oliver is a neighborhood in the Eastern district of Baltimore, Maryland. Its boundaries are the south side of North Avenue, the east side of Ensor Street, the west side of Broadway, and the north side of Biddle Street. This neighborhood, adjacent t ...

.

Blue baby syndrome

pediatric

Pediatrics ( also spelled ''paediatrics'' or ''pædiatrics'') is the branch of medicine that involves the medical care of infants, children, adolescents, and young adults. In the United Kingdom, paediatrics covers many of their youth until the ...

cardiologist Helen Taussig

Helen Brooke Taussig (May 24, 1898 – May 20, 1986) was an American cardiologist, working in Baltimore and Boston, who founded the field of pediatric cardiology. She is credited with developing the concept for a procedure that would extend the l ...

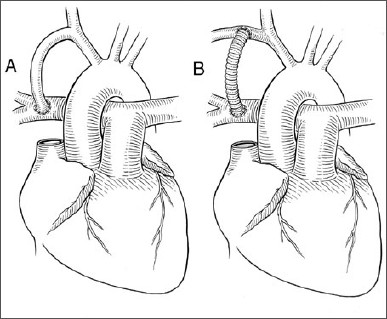

, who was seeking a surgical solution to a complex and fatal four-part heart anomaly called tetralogy of Fallot

Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF), formerly known as Steno-Fallot tetralogy, is a congenital heart defect characterized by four specific cardiac defects. Classically, the four defects are:

*pulmonary stenosis, which is narrowing of the exit from the r ...

(also known as blue baby syndrome, although other cardiac anomalies produce blueness, or cyanosis

Cyanosis is the change of body tissue color to a bluish-purple hue as a result of having decreased amounts of oxygen bound to the hemoglobin in the red blood cells of the capillary bed. Body tissues that show cyanosis are usually in locations ...

). In infants born with this defect, blood is shunted past the lungs, thus creating oxygen deprivation and a blue pallor. Having treated many such patients in her work in Hopkins's Harriet Lane Home, Taussig was desperate to find a surgical cure. According to the accounts in Thomas' 1985 autobiography and in a 1967 interview with medical historian Peter Olch, Taussig suggested only that it might be possible to "reconnect the pipes" in some way to increase the level of blood flow to the lungs, but did not suggest how this could be accomplished. Blalock and Thomas realized immediately that the answer lay in a procedure they had perfected for a different purpose in their Vanderbilt work, involving the anastomosis

An anastomosis (, plural anastomoses) is a connection or opening between two things (especially cavities or passages) that are normally diverging or branching, such as between blood vessels, leaf veins, or streams. Such a connection may be norm ...

(joining) of the subclavian artery

In human anatomy, the subclavian arteries are paired major arteries of the upper thorax, below the clavicle. They receive blood from the aortic arch. The left subclavian artery supplies blood to the left arm and the right subclavian artery suppl ...

to the pulmonary artery

A pulmonary artery is an artery in the pulmonary circulation that carries deoxygenated blood from the right side of the heart to the lungs. The largest pulmonary artery is the ''main pulmonary artery'' or ''pulmonary trunk'' from the heart, and ...

, which had the effect of increasing blood flow to the lungs. Thomas was charged with the task of first creating a blue baby-like condition in a dog, and then correcting the condition by means of the pulmonary-to-subclavian anastomosis. Among the dogs on whom Thomas operated was one named Anna, who became the first long-term survivor of the operation and the only animal to have her portrait hung on the walls of Johns Hopkins. In nearly two years of laboratory work involving 200 dogs, Thomas was able to replicate two of the four cardiac anomalies involved in tetralogy of Fallot

Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF), formerly known as Steno-Fallot tetralogy, is a congenital heart defect characterized by four specific cardiac defects. Classically, the four defects are:

*pulmonary stenosis, which is narrowing of the exit from the r ...

. He did demonstrate that the corrective procedure was not lethal, thus persuading Blalock that the operation could be safely attempted on a human patient. Blalock was impressed with Thomas' work; when he inspected the procedure performed on Anna, he reportedly said, "This looks like something the Lord made." Even though Thomas knew he was not allowed to operate on patients at that time, he still followed Blalock's rules and assisted him during surgery.

Decisive surgery

On November 29, 1944, the procedure was first tried on an eighteen-month-old infant namedEileen Saxon Eileen Saxon, sometimes referred to as "The Blue Baby", was the patient in an operation that ushered in the modern era of cardiac surgery.

She had a condition called Tetralogy of Fallot, one of the primary congenital defects that lead to blue baby ...

. The blue baby syndrome had made her lips and fingers turn blue, with the rest of her skin having a very faint blue tinge. She could only take a few steps before beginning to breathe heavily. Because no instruments for cardiac surgery then existed, Thomas adapted the needles and clamps for the procedure from those in use in the animal lab. During the surgery itself, at Blalock's request, Thomas stood on a step stool at Blalock's shoulder and coached him step by step through the procedure. Thomas performed the operation hundreds of times on a dog, whereas Blalock did so only once as Thomas' assistant. The surgery was not completely successful, though it did prolong the infant's life for several months. Blalock and his team operated again on an 11-year-old girl, this time with complete success, and the patient was able to leave the hospital three weeks after the surgery. Next, they operated upon a six-year-old boy, who dramatically regained his color at the end of the surgery. The three cases formed the basis for the article that was published in the May 1945 issue of the ''Journal of the American Medical Association

''The Journal of the American Medical Association'' (''JAMA'') is a peer-reviewed medical journal published 48 times a year by the American Medical Association. It publishes original research, reviews, and editorials covering all aspects of b ...

'', giving credit to Blalock and Taussig for the procedure. Thomas received no mention.

News of this groundbreaking story was circulated around the world by the

News of this groundbreaking story was circulated around the world by the Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American non-profit news agency headquartered in New York City. Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association. It produces news reports that are distributed to its members, U.S. new ...

. Newsreels

A newsreel is a form of short documentary film, containing news stories and items of topical interest, that was prevalent between the 1910s and the mid 1970s. Typically presented in a cinema, newsreels were a source of current affairs, inform ...

touted the event, greatly enhancing the status of Johns Hopkins and solidifying the reputation of Blalock, who had been regarded as a maverick up until that point by some in the Hopkins old guard. Thomas' contribution remained unacknowledged, both by Blalock and by Hopkins. Within a year, the operation known as the Blalock-Thomas-Taussig shunt had been performed on more than 200 patients at Hopkins, with parents bringing their suffering children from thousands of miles away.

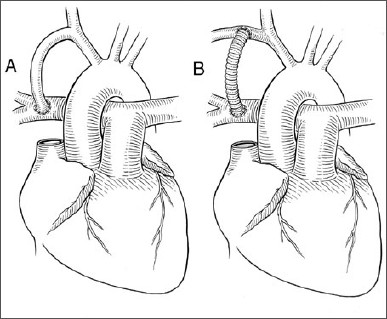

Skills

Thomas' surgical techniques included one he developed in 1946 for improving circulation in patients whosegreat vessels

Great vessels are the large vessels that bring blood to and from the heart. These are:

*Superior vena cava

*Inferior vena cava

*Pulmonary arteries

* Pulmonary veins

*Aorta

Transposition of the great vessels is a group of congenital heart defec ...

(the aorta

The aorta ( ) is the main and largest artery in the human body, originating from the left ventricle of the heart and extending down to the abdomen, where it splits into two smaller arteries (the common iliac arteries). The aorta distributes o ...

and the pulmonary artery) were transposed. A complex operation called an atrial septectomy, the procedure was executed so flawlessly by Thomas that Blalock, upon examining the nearly undetectable suture line, was prompted to remark, "Vivien, this looks like something the Lord made." To the host of young surgeons Thomas trained during the 1940s, he became a figure of legend, the model of a dexterous and efficient cutting surgeon. "Even if you'd never seen surgery before, you could do it because Vivien made it look so simple," the renowned surgeon Denton Cooley told '' Washingtonian'' magazine in 1989. "There wasn't a false move, not a wasted motion, when he operated." Surgeons like Cooley, along with Alex Haller, Frank Spencer, Rowena Spencer, and others credited Thomas with teaching them the surgical technique that placed them at the forefront of medicine in the United States. Despite the deep respect Thomas was accorded by these surgeons and by the many Black lab assistants he trained at Hopkins, he was not well paid. He sometimes resorted to working as a bartender

A bartender (also known as a barkeep, barman, barmaid, or a mixologist) is a person who formulates and serves alcoholic or soft drink beverages behind the bar, usually in a licensed establishment as well as in restaurants and nightclubs, but ...

, often at Blalock's parties. This led to the peculiar circumstance of his serving drinks to people he had been teaching earlier in the day. Eventually, after negotiations on his behalf by Blalock, he became the highest paid assistant at Johns Hopkins by 1946, and by far the highest paid African-American on the institution's rolls. Although Thomas never wrote or spoke publicly about his ongoing desire to return to college and obtain a medical degree, his widow, the late Clara Flanders Thomas, revealed in a 1987 interview with '' Washingtonian'' writer Katie McCabe that her husband had clung to the possibility of further education throughout the blue baby period, and had only abandoned the idea with great reluctance. Mrs. Thomas stated that in 1947, Thomas had investigated the possibility of enrolling in college and pursuing his dream of becoming a doctor, but had been deterred by the inflexibility of Morgan State University

Morgan State University (Morgan State or MSU) is a public historically black research university in Baltimore, Maryland. It is the largest of Maryland's historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs). In 1867, the university, then known a ...

, which refused to grant him credit for life experience and insisted that he fulfill the standard freshman requirements. Realizing that he would be 50 years old by the time he completed college and medical school, Thomas decided to give up the idea of further education.

Relations with Blalock

Vivien Thomas felt nervous when he first met Dr. Alfred Blalock because his friend, Charles Manlove, made it apparent that many people had a hard time working with him. However, Thomas felt as if Dr. Blalock was pleasant, relaxed, and informal during his interview, which provided excitement and comfort. Thomas quickly learned that Blalock moved quickly and expected his technicians to also be just as efficient. As Blalock performed experiments daily, Thomas observed thoroughly so that he would be able to recreate the steps when Blalock had other responsibilities to attend to. On the contrary, there were times where Blalock would lose his temper and use obscene profanity; this often bothered Thomas, and almost threatened their stable working relationship. During Thomas' time working at Vanderbilt in the lab, he struggled with his salary because he needed to be able to provide for himself, but he also was saving up to go back to school. After many encounters with Blalock about a pay raise and no results, Thomas was going to return to his old job as a carpenter. However, Blalock saw Thomas as a valuable asset and did everything he could to keep Thomas from leaving. Blalock's approach to the issue of Thomas's race was complicated and contradictory throughout their 34-year partnership. Thomas, a hard-working laboratory technician, was only paid a janitorial salary. However, white men performing an equivalent of Thomas' job were paid an appreciable dollar more per hour. On the one hand, he defended his choice of Thomas to his superiors at Vanderbilt and to Hopkins colleagues, and he insisted that Thomas accompany him in the operating room during the first series of tetralogy operations. On the other hand, there were limits to his tolerance, especially when it came to issues of pay, academic acknowledgment, and his social interaction outside of work. Tension with Blalock continued to build when he failed to recognize the contributions that Thomas had made in the world-famous blue baby procedure, which led to a rift in their relationship. Thomas was absent in official articles about the procedure, as well as in team pictures that included all of the doctors involved in the procedure. After Blalock's death from cancer in 1964 at the age of 65, Thomas stayed at Hopkins for 15 more years. In his role as director of Surgical Research Laboratories, he mentored a number of African-American lab assistants as well as Hopkins' first Black cardiac resident, Levi Watkins, Jr., whom Thomas assisted with his groundbreaking work in the use of the automatic implantable defibrillator. Thomas' nephew, Koco Eaton, graduated from the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, trained by many of the physicians his uncle had trained. Eaton trained inorthopedics

Orthopedic surgery or orthopedics ( alternatively spelt orthopaedics), is the branch of surgery concerned with conditions involving the musculoskeletal system. Orthopedic surgeons use both surgical and nonsurgical means to treat musculoskeletal ...

and is now the team doctor for the Tampa Bay Rays

The Tampa Bay Rays are an American professional baseball team based in St. Petersburg, Florida. The Rays compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the American League (AL) East division. Since its inception, the team's home v ...

.

Institutional acknowledgment

In 1968, the surgeons Thomas trained — who had then become chiefs of surgical departments throughout America — commissioned the painting of his portrait (by Bob Gee, oil on canvas, 1969, The Johns Hopkins Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives) and arranged to have it hung next to Blalock's in the lobby of the Alfred Blalock Clinical Sciences Building. In 1976,Johns Hopkins University

Johns Hopkins University (Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private research university in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1876, Johns Hopkins is the oldest research university in the United States and in the western hemisphere. It consi ...

presented Thomas with an honorary doctorate. Due to certain restrictions, he received an honorary Doctor of Laws

A Doctor of Law is a degree in law. The application of the term varies from country to country and includes degrees such as the Doctor of Juridical Science (J.S.D. or S.J.D), Juris Doctor (J.D.), Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.), and Legum Doctor ...

, rather than a medical doctorate

Doctor of Medicine (abbreviated M.D., from the Latin ''Medicinae Doctor'') is a medical degree, the meaning of which varies between different jurisdictions. In the United States, and some other countries, the M.D. denotes a professional degre ...

, but it did allow the staff and students of Johns Hopkins Hospital

The Johns Hopkins Hospital (JHH) is the teaching hospital and biomedical research facility of the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, located in Baltimore, Maryland, U.S. It was founded in 1889 using money from a bequest of over $7 million (1873 ...

and Johns Hopkins School of Medicine

The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine (JHUSOM) is the medical school of Johns Hopkins University, a private research university in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1893, the School of Medicine shares a campus with the Johns Hopkins Hospi ...

to call him doctor. After having worked there for 37 years, Thomas was also finally appointed to the faculty of the School of Medicine as Instructor of Surgery. Due to his lack of an official medical degree, he was never allowed to operate on a living patient.

In July 2005, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine began the practice of splitting incoming first-year students into four colleges, each named for famous Hopkins faculty members who had major impacts on the history of medicine. Thomas was chosen as one of the four, along with Helen Taussig

Helen Brooke Taussig (May 24, 1898 – May 20, 1986) was an American cardiologist, working in Baltimore and Boston, who founded the field of pediatric cardiology. She is credited with developing the concept for a procedure that would extend the l ...

, Florence Sabin

Florence Rena Sabin (November 9, 1871 – October 3, 1953) was an American medical scientist. She was a pioneer for women in science; she was the first woman to hold a full professorship at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, the first woman ...

, and Daniel Nathans

Daniel Nathans (October 30, 1928 – November 16, 1999) was an American microbiologist. He shared the 1978 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for the discovery of restriction enzymes and their application in restriction mapping.

Early life a ...

.

Personal life and death

In the summer of 1933, Thomas met Clara Beatrice Flanders. Thomas was so fond of Flanders that he married her that same year on December 22, and the newly wed couple moved to Nashville, Tennessee. The couple had two daughters. Olga Fay, the oldest, was born in 1934, and Theodosia Patricia was born 4 years later in 1938. In 1941, Thomas and his family moved toBaltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore was ...

so that he could continue working with Blalock.

In 1971, Thomas was recognized for all his hard work "behind the scenes" with a ceremony, and the presentation of his portrait to the medical institution. Thomas spoke humbly to the full capacity auditorium. He stated that he lived in humble satisfaction that he was able to help solve some of the world's numerous health problems. He was overjoyed that he was finally getting recognition for his significant role in the research leading to developmental skills that many surgeons now practice.

On July 1, 1976, Thomas was appointed to the faculty as an Instructor of Surgery; Thomas served as the Instructor of Surgery for 3 years and retired in 1979. Following his retirement, Thomas began work on an autobiography. He died of pancreatic cancer

Pancreatic cancer arises when cells in the pancreas, a glandular organ behind the stomach, begin to multiply out of control and form a mass. These cancerous cells have the ability to invade other parts of the body. A number of types of pancr ...

on November 26, 1985, and the book was published just days later.

Legacy

Having learned about Thomas on the day of his death, ''Washingtonian'' writer Katie McCabe brought his story to public attention in a 1989 article entitled "Like Something the Lord Made," which won the 1990National Magazine Award

The National Magazine Awards, also known as the Ellie Awards, honor print and digital publications that consistently demonstrate superior execution of editorial objectives, innovative techniques, noteworthy enterprise and imaginative design. Or ...

for Feature Writing and inspired the PBS documentary ''Partners of the Heart'', which was broadcast in 2003 on PBS's American Experience

''American Experience'' is a television program airing on the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) in the United States. The program airs documentaries, many of which have won awards, about important or interesting events and people in American his ...

and won the Organization of American Historians's Erik Barnouw Award for Best History Documentary in 2004. McCabe's article, brought to Hollywood by Washington, D.C. dentist Irving Sorkin, formed the basis for the Emmy

The Emmy Awards, or Emmys, are an extensive range of awards for artistic and technical merit for the American and international television industry. A number of annual Emmy Award ceremonies are held throughout the calendar year, each with the ...

and Peabody Award

The George Foster Peabody Awards (or simply Peabody Awards or the Peabodys) program, named for the American businessman and philanthropist George Peabody, honor the most powerful, enlightening, and invigorating stories in television, radio, and ...

-winning 2004 HBO film ''Something the Lord Made

''Something the Lord Made'' is a 2004 American made-for-television biographical drama film about the black cardiac pioneer Vivien Thomas (1910–1985) and his complex and volatile partnership with white surgeon Alfred Blalock (1899–1964), th ...

''.

Thomas's legacy as an educator and scientist continued with the institution of the Vivien Thomas Young Investigator Awards, given by the Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesiology beginning in 1996. In 1993, the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation

The Congressional Black Caucus Foundation (CBCF) is an American educational foundation. It conducts research on issues affecting African Americans, publishes a yearly report on key legislation, and sponsors issue forums, leadership seminars and ...

instituted the Vivien Thomas Scholarship for Medical Science and Research sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline

GSK plc, formerly GlaxoSmithKline plc, is a British multinational pharmaceutical and biotechnology company with global headquarters in London, England. Established in 2000 by a merger of Glaxo Wellcome and SmithKline Beecham. GSK is the tent ...

. In fall 2004, the Baltimore City Public School System

Baltimore City Public Schools (BCPS), also referred to as Baltimore City Public School System (BCPSS) or City Schools, is a public school district in the city of Baltimore, state of Maryland, United States. It serves the youth of Baltimore Cit ...

opened the Vivien T. Thomas Medical Arts Academy. In the halls of the school hangs a replica of Thomas' portrait commissioned by his surgeon-trainees in 1969. The ''Journal of Surgical Case Reports'' announced in January 2010 that its annual prizes for the best case report written by a doctor and best case report written by a medical student would be named after Thomas.

Vanderbilt University Medical Center created the Vivien A. Thomas Award for Excellence in Clinical Research, recognizing excellence in conducting clinical research.

See also

* Daniel Hale WilliamsReferences

Bibliography

* ** Reprinted — ** Reprinted in ** Revised as * * (originally published as ''Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery: Vivien Thomas and His Work with Alfred Blalock'') * (2003) Timmermans Stefan, "A Black Technician and Blue Babies" in ''Social Studies of Science'' 33:2 (April 2003), 197–229. * (2006) Tsung O. Cheng, " Hamilton Naki andChristiaan Barnard

Christiaan Neethling Barnard (8 November 1922 – 2 September 2001) was a South African cardiac surgeon who performed the world's first human-to-human heart transplant operation. On 3 December 1967, Barnard transplanted the heart of accident-v ...

Versus Vivien Thomas and Alfred Blalock: Similarities and Dissimilarities" in ''American Journal of Cardiology

''The American Journal of Cardiology'' is a biweekly peer-reviewed scientific journal in the field of cardiology and general cardiovascular disease. The editor-in-chief is William C. Roberts. It supersedes the ''Transactions of the American Colleg ...

'' 97:3 (February 1, 2006), 435–436.

* (2003)Partners of the Heart.

''

American Experience

''American Experience'' is a television program airing on the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) in the United States. The program airs documentaries, many of which have won awards, about important or interesting events and people in American his ...

''

* (2004) "Something the Lord Made

''Something the Lord Made'' is a 2004 American made-for-television biographical drama film about the black cardiac pioneer Vivien Thomas (1910–1985) and his complex and volatile partnership with white surgeon Alfred Blalock (1899–1964), th ...

", HBO movie, Portrayed by Mos Def

Yasiin Bey (; born Dante Terrell Smith, December 11, 1973), previously and more commonly known by his stage name Mos Def (), is an American rapper, singer, songwriter, and actor. His hip hop career began in 1994, alongside his siblings in the s ...

External links

Blue Baby Operation Exhibit

{{DEFAULTSORT:Thomas, Vivien American cardiac surgeons Johns Hopkins University faculty Johns Hopkins Hospital physicians 1910 births 1985 deaths People from New Iberia, Louisiana Deaths from pancreatic cancer African-American inventors African-American physicians African-American scientists American scientists Janitors 20th-century surgeons 20th-century African-American people