Virginia Hall on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Virginia Hall Goillot

Hall was a pioneer as a World War II secret agent and had to learn on her own the "exacting tasks of being available, arranging contacts, recommending who to bribe and where to hide, soothing the jagged nerves of agents on the run and supervising the distribution of wireless sets." The network (or circuit) of SOE agents she founded was named Heckler. Among her recruits were gynecologist Jean Rousset and Germaine Guérin, the owner of a prominent brothel in Lyon. Guérin made several

Hall was a pioneer as a World War II secret agent and had to learn on her own the "exacting tasks of being available, arranging contacts, recommending who to bribe and where to hide, soothing the jagged nerves of agents on the run and supervising the distribution of wireless sets." The network (or circuit) of SOE agents she founded was named Heckler. Among her recruits were gynecologist Jean Rousset and Germaine Guérin, the owner of a prominent brothel in Lyon. Guérin made several

On her return to London, SOE leaders declined to send Hall back to France as an agent despite her requests. She was compromised, they said, and too much at risk. However, she took a wireless course and contacted the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS) about a job. She was hired by the Special Operations Branch at the low rank and pay of a second lieutenant and on March 21, 1944, returned to France, arriving by motor gunboat at Beg-an-Fry east of

On her return to London, SOE leaders declined to send Hall back to France as an agent despite her requests. She was compromised, they said, and too much at risk. However, she took a wireless course and contacted the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS) about a job. She was hired by the Special Operations Branch at the low rank and pay of a second lieutenant and on March 21, 1944, returned to France, arriving by motor gunboat at Beg-an-Fry east of  Hall was next given the job of helping the Maquis in southern France harass the Germans in support of the Allied invasion of the south, Operation Dragoon, which would take place on August 15, 1944. In July, Hall was ordered to go to

Hall was next given the job of helping the Maquis in southern France harass the Germans in support of the Allied invasion of the south, Operation Dragoon, which would take place on August 15, 1944. In July, Hall was ordered to go to

DSC DSC may refer to:

Academia

* Doctor of Science (D.Sc.)

* District Selection Committee, an entrance exam in India

* Doctor of Surgical Chiropody, superseded in the 1960s by Doctor of Podiatric Medicine

Educational institutions

* Dalton State Col ...

, Croix de Guerre, (April 6, 1906 – July 8, 1982), code named Marie and Diane, was an American who worked with the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

's clandestine Special Operations Executive

The Special Operations Executive (SOE) was a secret British World War II organisation. It was officially formed on 22 July 1940 under Minister of Economic Warfare Hugh Dalton, from the amalgamation of three existing secret organisations. Its pu ...

(SOE) and the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS) in France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

. The objective of SOE and OSS was to conduct espionage

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information (intelligence) from non-disclosed sources or divulging of the same without the permission of the holder of the information for a tangib ...

, sabotage

Sabotage is a deliberate action aimed at weakening a polity, effort, or organization through subversion, obstruction, disruption, or destruction. One who engages in sabotage is a ''saboteur''. Saboteurs typically try to conceal their identitie ...

and reconnaissance

In military operations, reconnaissance or scouting is the exploration of an area by military forces to obtain information about enemy forces, terrain, and other activities.

Examples of reconnaissance include patrolling by troops (skirmisher ...

in occupied Europe against the Axis powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

, especially Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

. SOE and OSS agents in France allied themselves with resistance groups and supplied them with weapons and equipment parachuted in from England. After World War II Hall worked for the Special Activities Division

The Special Activities Center (SAC) is a division of the United States Central Intelligence Agency responsible for covert and paramilitary operations. The unit was named Special Activities Division (SAD) prior to 2015. Within SAC there are two ...

of the Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

(CIA).

Hall was a pioneering agent for the SOE, arriving in Vichy France

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its te ...

on 23 August 1941, the first female agent to take up residence in France. She created the Heckler network in Lyon

Lyon,, ; Occitan language, Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lionés'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, third-largest city and Urban area (France), second-largest metropolitan area of F ...

. Over the next 15 months, she "became an expert at support operations – organizing resistance movements; supplying agents with money, weapons, and supplies; helping downed airmen to escape; offering safe houses and medical assistance to wounded agents and pilots." She fled France in November 1942 to avoid capture by the Germans.

She returned to France as a wireless operator for the OSS in March 1944 as a member of the Saint network. Working in territory still occupied by the German army and mostly without the assistance of other OSS agents, she supplied arms, training, and direction to French resistance groups, called Maquisards, especially in Haute-Loire

Haute-Loire (; oc, Naut Léger or ''Naut Leir''; English: Upper Loire) is a landlocked department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region of south-central France. Named after the Loire River, it is surrounded by the departments of Loire, Ardèche, ...

where the Maquis cleared the department of German soldiers prior to the arrival of the American army in September 1944.

The Germans gave her the nickname ''Artemis,'' and the Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one orga ...

reportedly considered her "the most dangerous of all Allied spies." Having lost part of her leg in a hunting accident, Hall used a prosthesis she named "Cuthbert." She was also known as "The Limping Lady" by the Germans and as "Marie of Lyon" by many of the SOE agents she assisted.

Early life

Virginia Hall was born inBaltimore, Maryland

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

on April 6, 1906 to Barbara Virginia Hammel and Edwin Lee Hall. She attended Roland Park Country School

Roland Park Country School (RPCS) is an independent all-girls college preparatory school in Baltimore, Maryland, United States. It serves girls from kindergarten through grade 12. It is located on Roland Avenue in the northern area of Baltimore ...

and then Radcliffe College of Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of high ...

and Barnard College

Barnard College of Columbia University is a private women's liberal arts college in the borough of Manhattan in New York City. It was founded in 1889 by a group of women led by young student activist Annie Nathan Meyer, who petitioned Columbia ...

of Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

, where she studied French, Italian, and German. She also attended George Washington University

The George Washington University (GW or GWU) is a Private university, private University charter#Federal, federally chartered research university in Washington, D.C. Chartered in 1821 by the United States Congress, GWU is the largest Higher educat ...

, where she studied French and Economics. She wanted to finish her studies in Europe, so she traveled the Continent and studied in France, Germany, and Austria, finally landing an appointment as a Consular Service clerk at the American Embassy in Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officia ...

, Poland in 1931.

A few months later she transferred to Smyrna, known later as Izmir, Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula in ...

. In 1933, she tripped and accidentally shot herself in the right foot while hunting birds. Her leg was amputated below the knee and replaced with a wooden appendage which she named "Cuthbert". After losing her leg, she worked again as a consular clerk in Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 bridges. The isla ...

and in Tallinn

Tallinn () is the most populous and capital city of Estonia. Situated on a bay in north Estonia, on the shore of the Gulf of Finland of the Baltic Sea, Tallinn has a population of 437,811 (as of 2022) and administratively lies in the Harju '' ...

, Estonia

Estonia, formally the Republic of Estonia, is a country by the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, a ...

.

Hall made several attempts to become a diplomat with the United States Foreign Service

The United States Foreign Service is the primary personnel system used by the diplomatic service of the United States federal government, under the aegis of the United States Department of State. It consists of over 13,000 professionals carry ...

, but women were rarely hired. In 1937, she was turned down by the Department of State because of an obscure rule against hiring people with disabilities as diplomats. Even an appeal for her to be hired to President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

was unheeded. She resigned from the Department of State in March 1939, still a consular clerk.

World War II

Early in World War II in February 1940, Hall became an ambulance driver for the army of France. After the defeat of France in June 1940, she made her way toSpain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

where, by chance, she met a British intelligence officer named George Bellows. Bellows was impressed with her and gave her the telephone number of a "friend" who might be able to help her find employment in England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

. The friend was Nicolas Bodington

During the Second World War, Nicolas Redner Bodington OBE (6 June 1904 – 3 July 1974) served in the F section of the Special Operations Executive. He took part in four missions to France.

Life

Pre-war

Nicolas Bodington was the son of Oli ...

, who worked for the newly-created Special Operations Executive (SOE).

Special Operations Executive

Hall joined the SOE in April 1941 and after training arrived inVichy France

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its te ...

, unoccupied by Germany and nominally independent at that time, on August 23, 1941. She was the second female agent to be sent to France by SOE's F (France) Section, and the first to remain there for a lengthy period of time. (SOE F section would send 41 female agents to France during World War II, of whom 26 would survive the war.) Hall's cover was as a reporter for the ''New York Post

The ''New York Post'' (''NY Post'') is a conservative daily tabloid newspaper published in New York City. The ''Post'' also operates NYPost.com, the celebrity gossip site PageSix.com, and the entertainment site Decider.com.

It was established ...

'' which gave her license to interview people, gather information and file stories filled with details useful to military planners. She based herself in Lyon

Lyon,, ; Occitan language, Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lionés'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, third-largest city and Urban area (France), second-largest metropolitan area of F ...

. She turned away from her "chic Parisian wardrobe" to become inconspicuous and often quickly changed her appearance through make-up and disguise.

Hall was a pioneer as a World War II secret agent and had to learn on her own the "exacting tasks of being available, arranging contacts, recommending who to bribe and where to hide, soothing the jagged nerves of agents on the run and supervising the distribution of wireless sets." The network (or circuit) of SOE agents she founded was named Heckler. Among her recruits were gynecologist Jean Rousset and Germaine Guérin, the owner of a prominent brothel in Lyon. Guérin made several

Hall was a pioneer as a World War II secret agent and had to learn on her own the "exacting tasks of being available, arranging contacts, recommending who to bribe and where to hide, soothing the jagged nerves of agents on the run and supervising the distribution of wireless sets." The network (or circuit) of SOE agents she founded was named Heckler. Among her recruits were gynecologist Jean Rousset and Germaine Guérin, the owner of a prominent brothel in Lyon. Guérin made several safehouse

A safe house (also spelled safehouse) is, in a generic sense, a secret place for sanctuary or suitable to hide people from the law, hostile actors or actions, or from retribution, threats or perceived danger. It may also be a metaphor.

Histori ...

s available to Hall and passed along tidbits of information she and her female employees heard from German officers visiting the brothel.

The official historian of the SOE, M. R. D. Foot, said that the motto of every successful secret agent was "''dubito, ergo sum''" ("I doubt, therefore I survive."). Hall's lengthy tenure in France without being captured illustrates her caution. In October 1941, she sensed danger and declined to attend a meeting of SOE agents in Marseille

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Fra ...

which the French police raided, capturing a dozen agents. After that debacle, Hall was one of the few SOE agents still at large in France and the only one with a means of transmitting information to London. George Whittinghill, an American diplomat in Lyon, allowed her to smuggle reports and letters to London in the diplomatic pouch.

The winter of 1941–42 was miserable for Hall. In a letter she said that if SOE would send her a piece of soap she would be "both very happy and much cleaner." In the absence of an SOE wireless operator her access to the American diplomatic pouch was the only means the few agents left at large in France had of communicating with London. She continued building contacts in southern France and she assisted in the brief missions of SOE agents Peter Churchill

Peter Morland Churchill, (14 January 1909 – 1 May 1972) was a British Special Operations Executive (SOE) officer in France during the Second World War. His wartime operations, which resulted in his capture and imprisonment in German concentra ...

and Benjamin Cowburn

Benjamin Hodkinson Cowburn , Croix de Guerre, Chevalier of the Legion of Honour (1909–1994), code named ''Benoit'' and ''Germain,'' was an agent of the United Kingdom's clandestine Special Operations Executive (SOE) organization during World W ...

and earned high compliments from both. She avoided contact with an SOE agent sent to Lyon named Georges Duboudin and refused to introduce him to her contacts. She regarded him as amateurish and lax in security. When SOE headquarters directed that Duboudin should supervise her, she told SOE to "lay off." She worked as little as possible with Philippe de Vomécourt

Philippe Albert de Crevoisier, Baron de Vomécourt (16 January 1902 – 20 December 1964), code names Gauthier and Antoine, was an agent of the United Kingdom's clandestine Special Operations Executive (SOE) organization in World War II. He ...

, who, although an authentic French Resistance leader, was lax in security and grandiose in his ambitions. In August 1942, SOE agent Richard Heslop met with her and described her as a "girl" (she was 36) who lived in a gloomy apartment, but he relied on her to facilitate communications with other agents. When a suspicious Heslop demanded to know who "Cuthbert" was she showed him by banging her wooden foot against a table leg producing a hollow sound.

Another task Hall took on was helping British airmen, shot down or crashed over Europe, escape and return to England. Downed airmen who found their way to Lyon were told to go to the American Consulate and say they were a "friend of Olivier." "Olivier" was Hall and she, with the help of brothel-owner Guerrin and other friends, hid, fed, and helped dozens of airmen escape France to neutral Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

and hence back to England.

The French nicknamed her "la dame qui boite" and the Germans put "the limping lady" on their most wanted list.

The jailbreak

Hall learned that the 12 agents arrested by the French police in October 1941 were incarcerated at the Mauzac prison near Bergerac. Wireless operatorGeorges Bégué

Georges Pierre André Bégué (22 November 1911 – 18 December 1993), Social Security Death Index code named Bombproof, was a French engineer and agent of the United Kingdom's clandestine organization, the Special Operations Executive (S ...

smuggled out letters to Hall from the prison and she recruited Gaby Bloch, wife of the prisoner Jean-Pierre Bloch, as an ally to plan an escape. Bloch visited the prison frequently to bring food and other items to her husband, including tins of sardine

"Sardine" and "pilchard" are common names for various species of small, oily forage fish in the herring family Clupeidae. The term "sardine" was first used in English during the early 15th century, a folk etymology says it comes from the It ...

s. The tools she smuggled in and the sardine tins enabled Bégué to make a key to the door of the barracks where the prisoners were kept. Hall, too well known to visit the prison, assembled safe houses, vehicles, and helpers. A priest smuggled in a radio to Bégué, and from within the prison, he began transmitting to London.

On July 15, 1942, the prisoners escaped and, after hiding in the woods while an intense manhunt took place, all of them met up with Hall in Lyon by August 11. From there, they were smuggled to Spain and thence back to England. The official historian of SOE, M. R. D. Foot, called the escape "one of the war's most useful operations of its kind." Several of the escapees returned later to France and became leaders of SOE networks.

Germans retaliate

The Germans were furious about the escape from Mauzac prison and the laxity of the French police in allowing the escape. The Gestapo flooded Vichy France with 500 agents and the Abwehr also stepped up operations to infiltrate and destroy the fledgling French Resistance and the SOE networks. The Germans focused on Lyon, the center of the resistance. Hall had counted on contacts she had with the French police to protect her, but, under pressure from the Germans, her police contacts were no longer reliable. In May 1942, Hall had agreed to have messages from the Gloria Network, a French-run resistance movement based in Paris, transmitted to SOE in London. In August Gloria was infiltrated by aRoman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

priest and Abwehr agent named Robert Alesch and its leadership was captured by the Abwehr. Alesch also made contact with Hall in August, claiming to be an agent of Gloria and offering intelligence of apparently high value. She had doubts about Alesch, especially when she learned that Gloria had been destroyed, but was persuaded of his bona fides, as was the London headquarters of SOE. Alesch was able to penetrate Hall's network of contacts, including the capture of wireless operators and the sending of false messages to London in her name.

Escape

On November 7, 1942, the American Consulate in Lyon told Hall that an allied invasion ofNorth Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

was imminent. In response to the invasion, on November 8, the Germans moved to occupy Vichy France. Hall anticipated correctly that the suppression by the Gestapo and Abwehr would become even more severe and she fled Lyon without telling anyone, including her closest contacts. She escaped by train from Lyon to Perpignan, then, with a guide, walked over a 7,500 foot pass in the Pyrenees

The Pyrenees (; es, Pirineos ; french: Pyrénées ; ca, Pirineu ; eu, Pirinioak ; oc, Pirenèus ; an, Pirineus) is a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. It extends nearly from its union with the Cantabrian Mountains to ...

to Spain, covering up to 50 miles over two days in considerable discomfort.

Hall had named her artificial foot "Cuthbert", and she signaled to SOE before her escape that she hoped that "Cuthbert" would not trouble her on the way. The SOE did not understand the reference and replied, "If Cuthbert troublesome, eliminate him." After arriving in Spain, she was arrested by the Spanish authorities for illegally crossing the border, but the American Embassy eventually secured her release. She worked for SOE for a time in Madrid, then returned to London in July 1943 where she was quietly made an honorary Member of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established o ...

(MBE).

Office of Strategic Services

On her return to London, SOE leaders declined to send Hall back to France as an agent despite her requests. She was compromised, they said, and too much at risk. However, she took a wireless course and contacted the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS) about a job. She was hired by the Special Operations Branch at the low rank and pay of a second lieutenant and on March 21, 1944, returned to France, arriving by motor gunboat at Beg-an-Fry east of

On her return to London, SOE leaders declined to send Hall back to France as an agent despite her requests. She was compromised, they said, and too much at risk. However, she took a wireless course and contacted the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS) about a job. She was hired by the Special Operations Branch at the low rank and pay of a second lieutenant and on March 21, 1944, returned to France, arriving by motor gunboat at Beg-an-Fry east of Roscoff

Roscoff (; br, Rosko) is a commune in the Finistère département of Brittany in northwestern France.

Roscoff is renowned for its picturesque architecture, labelled (small town of character) since 2009. Roscoff is also a traditional departure ...

in Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica during the period ...

. Her artificial leg prevented her from parachuting.

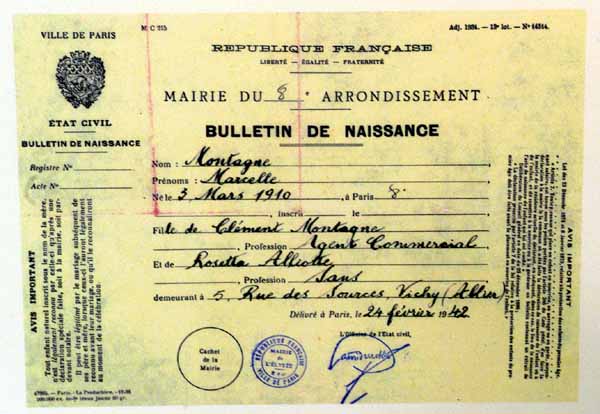

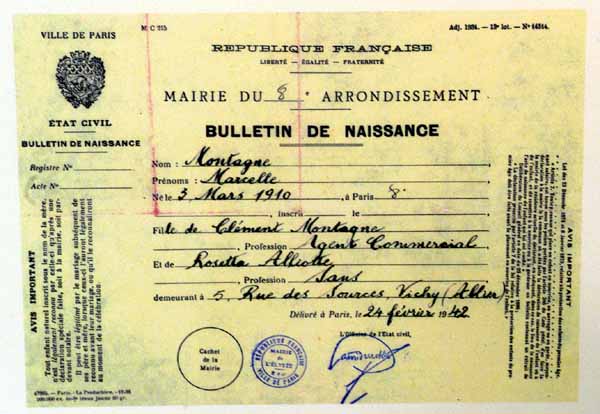

OSS provided her with a forged French identification card in the name of Marcelle Montagne. Her codename was Diane. The objective of the OSS teams was to arm and train the resistance groups, called Maquis, so they could support the Allied invasion of Normandy, which would take place on June 6, 1944, with sabotage and guerrilla activities.

Hall was disguised as an older woman, with gray hair and her teeth filed down to resemble that of a peasant woman. She disguised her limp with the shuffle of an old woman. Landing with her was Henri Lassot, 62 years old. Lassot was the organiser and leader of the new Saint network, it being too radical a thought that a woman could lead an SOE or OSS network of agents. She was Lassot's wireless operator. They were the fourth and fifth OSS agents to arrive in France. Lassot carried with him one million francs, equivalent to 5,000 British pounds; Hall had 500,000 francs with her. Hall quickly separated herself from Lassot whom she characterized as too talkative and a security risk, instructing her contacts not to tell him where she was. Aware that her accent would reveal that she was not French, she engaged a French woman, Madame Rabut, to accompany and speak for her.

From March to July 1944, Hall roamed around France south of Paris, posing sometimes as an elderly milkmaid (and on one occasion selling cheese she had made to a group of German soldiers). She found and organized drop zones, established several safe houses, and made and renewed contacts, notably with Philippe de Vomecourt, in the Resistance. She organized and supplied with arms several resistance groups of a hundred men each in the Cher and Cosne. She unsuccessfully attempted to organize a jailbreak to gain freedom for three men she called her nephews, captives of the Germans in Paris. Her resistance groups undertook many successful small-scale attacks on infrastructure and German soldiers.

Haute-Loire

Haute-Loire (; oc, Naut Léger or ''Naut Leir''; English: Upper Loire) is a landlocked department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region of south-central France. Named after the Loire River, it is surrounded by the departments of Loire, Ardèche, ...

department, arriving July 14, quitting her disguise, and establishing her headquarters in a barn near Le Chambon-sur-Lignon

Le Chambon-sur-Lignon (, literally "Le Chambon on Lignon"; oc, Lo Chambon, label=Auvergnat) is a commune in the Haute-Loire department in south-central France.

Residents have been primarily Huguenot or Protestant since the 17th century. Durin ...

. As a woman with the rank of second lieutenant she had problems asserting her authority over the Maquis groups and the self-proclaimed colonels heading them. She complained to OSS headquarters, "you send people out ostensibly to work with me and for me, but you do not give me the necessary authority."

She told the Maquis leaders that she would finance them and give them arms on condition that they would be advised by her, but the prickly Maquis leaders continued to be a problem. The three planeloads of supplies she received in late July and the money she distributed for expenses gained their grudging acquiescence.

The three battalions of Maquisards (about 1,500 men) in her area undertook a number of successful sabotage operations. Now part of the French Forces of the Interior

The French Forces of the Interior (french: Forces françaises de l'Intérieur) were French resistance fighters in the later stages of World War II. Charles de Gaulle used it as a formal name for the resistance fighters. The change in designation ...

(FFI), they forced the German occupiers to withdraw from Le Puy-en-Velay

Le Puy-en-Velay (, literally ''Le Puy in Velay''; oc, Lo Puèi de Velai ) is the prefecture of the Haute-Loire department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region of south-central France.

Located near the river Loire, the city is famous for its c ...

and head north with the rest of the retreating German forces. Belatedly, a Jedburgh

Jedburgh (; gd, Deadard; sco, Jeddart or ) is a town and former royal burgh in the Scottish Borders and the traditional county town of the historic county of Roxburghshire, the name of which was randomly chosen for Operation Jedburgh in s ...

team, called Jeremy, of three men parachuted in on August 25 to undertake the training and supply of the battalions. Hall commented wryly, "this was after the Germans had been liquidated in the department of the Haute Loire and Le Puy liberated."

Hall and several of the British and American military officers working for her left the Haute Loire and arrived in Paris on September 22. Later, she and her OSS agent Paul Golliot journeyed to Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

to foment anti-Nazi resistance. With the collapse of the Nazis, Hall and Golliot returned to Paris in April 1945. She wrote reports and identified people who had helped her and were deserving of commendations and then resigned from OSS.

Postwar and death

After the war, Hall visited Lyon to learn the fate of the people who had worked for her there. Her closest associates, brothel-owner Germaine Guérin and gynecologist Jean Rousset, had both been captured by the Germans and sent to concentration camps, but they survived. She arranged 80,000 francs (400 British pounds) compensation from theUnited Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

for Guérin, but most of her other helpers received nothing. Many of the people she knew had not survived – including the three men she called "nephews" who had been executed at Buchenwald concentration camp. The German agent and priest, Robert Alesch, who had betrayed her network in Lyon was captured after the war and executed in Paris.

Hall joined the Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

in 1947, one of the first women hired by the new agency. As a woman she was discriminated against, as the CIA later acknowledged. She was passed over for promotions, honors and work for which she was qualified despite the support and efforts from her superiors who knew her work directly. She was given a desk-bound job as an intelligence analyst to gather information about Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nation ...

penetration of European countries. She resigned in 1948 and then was rehired in 1950 for another desk job.

In the 1950s, she again headed ultra secret paramilitary operations in France as a model for setting up resistance groups in several European countries in case of a Soviet attack. She became a "sacred" presence and first woman operations officer in the entire covert action arm of the CIA and a valued member of the Special Activities Division

The Special Activities Center (SAC) is a division of the United States Central Intelligence Agency responsible for covert and paramilitary operations. The unit was named Special Activities Division (SAD) prior to 2015. Within SAC there are two ...

supporting undercover activities to prevent the spread of communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a ...

in Europe.

She received a poor performance reports from a superior who had never overseen her work. In 1966, she retired, at the mandatory retirement age of 60.

In the secret CIA report of her career, the CIA admitted that her fellow officers "felt she had been sidelined-shunted into backwater accounts because she had so much experience that she overshadowed her male colleagues, who felt threatened by her" and that "her experience and abilities were never properly utilized".

While in Haute-Loire, Hall had met and fallen in love with an OSS lieutenant, Paul Goillot, who worked with her. In 1957, the couple married after living together off-and-on for years. They retired to a farm in Barnesville, Maryland

Barnesville is a town in Montgomery County, Maryland, United States. It was incorporated in 1888. The population was 144 at the 2020 census.

History

The Maryland General Assembly chartered the town of Barnesville in 1811 and named it in honor ...

, where she lived until her death on July 8, 1982. Her husband survived her by five years. She is buried in the Druid Ridge Cemetery, Pikesville, Maryland.

Awards

For Virginia Hall's efforts in France, GeneralWilliam Joseph Donovan

William Joseph "Wild Bill" Donovan (January 1, 1883 – February 8, 1959) was an American soldier, lawyer, intelligence officer and diplomat, best known for serving as the head of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the precursor to the B ...

personally awarded her a Distinguished Service Cross The Distinguished Service Cross (D.S.C.) is a military decoration for courage. Different versions exist for different countries.

*Distinguished Service Cross (Australia)

The Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) is a military decoration awarded to ...

in September 1945 in recognition of her efforts in France, the only one awarded to a civilian woman in World War II. President Truman wanted a public award of the medal, but Hall demurred, stating that she was "still operational and most anxious to get busy." She was made an honorary Member of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established o ...

(MBE), and was awarded the Croix de Guerre with Palme by France.

Hall's refusal to talk and write about her World War II experiences resulted in her slipping into obscurity during her lifetime, but her death "triggered a new curiosity" which persisted into the 21st century.

In 1988 her name was added to the Military Intelligence Corps Hall of Fame. The French and British ambassadors in Washington honored her in 2006, on the 100th anniversary of her birth.

In 2016, a CIA field agent training facility was named the Virginia Hall Expeditionary Center. The CIA Museum gives five operatives individual sections in its catalog. One is Virginia Hall; the other four are men who went on to head the CIA. She was inducted into the Maryland Women's Hall of Fame

The Maryland Women's Hall of Fame (MWHF) recognizes significant achievements and statewide contributions made by women who are Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virgin ...

in 2019.

Legacy

Books

Her story has been told in several books, including: * * * a non-fiction book for ages 12–18. * a non-fiction book for ages 10 and older. * * * audience: ages 14 and up.Roger Wolcott Hall

Roger Wolcott Hall (May 20, 1919 in Baltimore, Maryland – 20 July 2008 in Windsor Hills, Delaware) was an American Army officer and spy in the Office of Strategic Services during World War II and the author of a humorous memoir of his exper ...

(no relation) also mentioned her in passing in his book (Reprinted: )

Films

IFC Films

IFC Films is an American film production and distribution company based in New York. It is an offshoot of IFC owned by AMC Networks. It distributes mainly independent films under its own name, select foreign films and documentaries under its ...

released '' A Call to Spy'' in October 2020, the first feature film about Virginia Hall. It had its world premiere at the Edinburgh International Film Festival

The Edinburgh International Film Festival (EIFF) is a film festival that runs for two weeks in June each year. Established in 1947, it is the world's oldest continually running film festival. EIFF presents both UK and international films (all ti ...

in June 2019, commemorating the 75th anniversary of D-Day. Hall is portrayed by Sarah Megan Thomas, and the film is directed by Lydia Dean Pilcher. The film went on to win the Audience Choice Award in Canada. ''A Call to Spy'' had its U.S. festival premiere at the 2020 Santa Barbara International Film Festival, where it was honored with the Anti-Defamation League's "Stand Up" Award.

The film ''A Woman of No Importance'' was announced in 2017, based on the book by Sonia Purnell and starring Daisy Ridley

Daisy Jazz Isobel Ridley (born 10 April 1992) is an English actress. She rose to prominence for her role as Rey in the ''Star Wars'' sequel trilogy: ''The Force Awakens'' (2015), ''The Last Jedi'' (2017), and ''The Rise of Skywalker'' (2019) ...

as Hall.

Notes

References

Sources

* * * **Reprinted: * * Partial preview of *Further reading

*External links

* * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Hall, Virginia 1906 births 1982 deaths 20th-century American writers American University alumni American amputees American shooting survivors American spies American women civilians in World War II Analysts of the Central Intelligence Agency Barnard College alumni Burials at Druid Ridge Cemetery Columbian College of Arts and Sciences alumni Death in Maryland Female recipients of the Croix de Guerre (France) Female resistance members of World War II Female wartime spies French Resistance members Honorary Members of the Order of the British Empire New York Post people People from Baltimore People of the Central Intelligence Agency People of the Office of Strategic Services Radcliffe College alumni Recipients of the Croix de Guerre (France) Recipients of the Distinguished Service Cross (United States) Special Operations Executive personnel World War II spies for the United States