Names

Various names have been applied to the conflict. "Vietnam War" is the most commonly used name in English. It has also been called the "Second Indochina War" and the "Vietnam conflict". Given that there have been several conflicts in Indochina, this particular conflict is known by its primary protagonists' names to distinguish it from others. In Vietnam, the war is generally known as the "Resistance war against the United States" (). It is also sometimes called the "American War".Background

The primary military organizations involved in the war were the By the 1950s, the conflict had become entwined with the Cold War. In January 1950, China and the Soviet Union recognized the Viet Minh's

By the 1950s, the conflict had become entwined with the Cold War. In January 1950, China and the Soviet Union recognized the Viet Minh's Transition period

At the

At the  In addition to the Catholics flowing south, over 130,000 "Revolutionary Regroupees" went to the north for "regroupment", expecting to return to the south within two years. The Viet Minh left roughly 5,000 to 10,000 cadres in the south as a base for future insurgency. The last French soldiers left South Vietnam in April 1956. The PRC completed its withdrawal from North Vietnam at around the same time.

Between 1953 and 1956, the North Vietnamese government instituted various agrarian reforms, including "rent reduction" and "land reform", which resulted in significant political oppression. During the land reform, testimony from North Vietnamese witnesses suggested a ratio of one execution for every 160 village residents, which extrapolated resulted in an initial estimation of nearly 100,000 executions nationwide. Because the campaign was concentrated mainly in the Red River Delta area, a lower estimate of 50,000 executions became widely accepted by scholars at the time. However, declassified documents from the Vietnamese and Hungarian archives indicate that the number of executions was much lower than reported at the time, although likely greater than 13,500. In 1956, leaders in Hanoi admitted to "excesses" in implementing this program and restored a large amount of the land to the original owners.

The south, meanwhile, constituted the State of Vietnam, with Bảo Đại as Emperor and Ngô Đình Diệm (appointed in July 1954) as his prime minister. Neither the United States government nor Ngô Đình Diệm's State of Vietnam signed anything at the 1954 Geneva Conference. With respect to the question of reunification, the non-communist Vietnamese delegation objected strenuously to any division of Vietnam, but lost out when the French accepted the proposal of Viet Minh delegate

In addition to the Catholics flowing south, over 130,000 "Revolutionary Regroupees" went to the north for "regroupment", expecting to return to the south within two years. The Viet Minh left roughly 5,000 to 10,000 cadres in the south as a base for future insurgency. The last French soldiers left South Vietnam in April 1956. The PRC completed its withdrawal from North Vietnam at around the same time.

Between 1953 and 1956, the North Vietnamese government instituted various agrarian reforms, including "rent reduction" and "land reform", which resulted in significant political oppression. During the land reform, testimony from North Vietnamese witnesses suggested a ratio of one execution for every 160 village residents, which extrapolated resulted in an initial estimation of nearly 100,000 executions nationwide. Because the campaign was concentrated mainly in the Red River Delta area, a lower estimate of 50,000 executions became widely accepted by scholars at the time. However, declassified documents from the Vietnamese and Hungarian archives indicate that the number of executions was much lower than reported at the time, although likely greater than 13,500. In 1956, leaders in Hanoi admitted to "excesses" in implementing this program and restored a large amount of the land to the original owners.

The south, meanwhile, constituted the State of Vietnam, with Bảo Đại as Emperor and Ngô Đình Diệm (appointed in July 1954) as his prime minister. Neither the United States government nor Ngô Đình Diệm's State of Vietnam signed anything at the 1954 Geneva Conference. With respect to the question of reunification, the non-communist Vietnamese delegation objected strenuously to any division of Vietnam, but lost out when the French accepted the proposal of Viet Minh delegate  From April to June 1955, Diệm eliminated any political opposition in the south by launching military operations against two religious groups: the

From April to June 1955, Diệm eliminated any political opposition in the south by launching military operations against two religious groups: the Diệm era, 1954–1963

Rule

In October 1956, Diệm launched a Land reform in South Vietnam, land reform program limiting the size of rice farms per owner. More than 1.8m acres of farm land became available for purchase by landless people. By 1960, the land reform process had stalled because many of Diem's biggest supporters were large land owners.

In May 1957, Diệm undertook a Ngô Đình Diệm presidential visit to the United States, ten-day state visit to the United States. President Eisenhower pledged his continued support, and a parade was held in Diệm's honor in New York City. Although Diệm was publicly praised, Secretary of State John Foster Dulles privately conceded that Diệm had to be backed because they could find no better alternative.

In October 1956, Diệm launched a Land reform in South Vietnam, land reform program limiting the size of rice farms per owner. More than 1.8m acres of farm land became available for purchase by landless people. By 1960, the land reform process had stalled because many of Diem's biggest supporters were large land owners.

In May 1957, Diệm undertook a Ngô Đình Diệm presidential visit to the United States, ten-day state visit to the United States. President Eisenhower pledged his continued support, and a parade was held in Diệm's honor in New York City. Although Diệm was publicly praised, Secretary of State John Foster Dulles privately conceded that Diệm had to be backed because they could find no better alternative.

Insurgency in the South, 1954–1960

Between 1954 and 1957, the Diệm government succeeded in preventing large-scale organized unrest in the countryside. In April 1957, insurgents launched an assassination campaign, referred to as "extermination of traitors". Seventeen people were killed in Châu Đốc massacre, an attack at a bar in Châu Đốc in July, and in September a district chief was killed with his family on a highway. By early 1959, however, Diệm had come to regard the (increasingly frequent) violence as an organized campaign and implemented Law 10/59, which made political violence punishable by death and property confiscation. There had been some division among former Viet Minh whose main goal was to hold the elections promised in the Geneva Accords, leading to "wildcat strike, wildcat" activities separate from the other communists and anti-GVN activists. Douglas Pike estimated that insurgents carried out 2,000 abductions, and 1,700 assassinations of government officials, village chiefs, hospital workers and teachers from 1957 to 1960. Violence between the insurgents and government forces increased drastically from 180 clashes in January 1960 to 545 clashes in September. In September 1960, Central Office for South Vietnam, COSVN, North Vietnam's southern headquarters, gave an order for a full scale coordinated uprising in South Vietnam against the government and 1/3 of the population was soon living in areas of communist control. In December 1960, North Vietnam formally created theNorth Vietnamese involvement

In March 1956, southern communist leader Lê Duẩn presented a plan to revive the insurgency entitled "The Road to the South" to the other members of the Politburo in Hanoi; however, as both China and the Soviets opposed confrontation at this time, Lê Duẩn's plan was rejected. Despite this, the North Vietnamese leadership approved tentative measures to revive the southern insurgency in December 1956. This decision was made at the 11th Plenary Session of the Lao Dong Central Committee. Communist forces were under a single command structure set up in 1958. In May 1958, North Vietnamese forces seized the transportation hub at Tchepone in Southern Laos near the demilitarized zone between North and South Vietnam.

In March 1956, southern communist leader Lê Duẩn presented a plan to revive the insurgency entitled "The Road to the South" to the other members of the Politburo in Hanoi; however, as both China and the Soviets opposed confrontation at this time, Lê Duẩn's plan was rejected. Despite this, the North Vietnamese leadership approved tentative measures to revive the southern insurgency in December 1956. This decision was made at the 11th Plenary Session of the Lao Dong Central Committee. Communist forces were under a single command structure set up in 1958. In May 1958, North Vietnamese forces seized the transportation hub at Tchepone in Southern Laos near the demilitarized zone between North and South Vietnam.

The North Vietnamese Communist Party approved a "people's war" on the South at a session in January 1959, and, in May, Group 559 was established to maintain and upgrade the Ho Chi Minh trail, at this time a six-month mountain trek through Laos. On 28 July, North Vietnamese and Pathet Lao forces invaded Laos, fighting the Royal Lao Army all along the border. Group 559 was headquartered in Na Kai, Houaphan province in northeast Laos close to the border. About 500 of the "regroupees" of 1954 were sent south on the trail during its first year of operation. The first arms delivery via the trail was completed in August 1959. In April 1960, North Vietnam imposed universal military conscription for adult males. About 40,000 communist soldiers infiltrated the south from 1961 to 1963.

The North Vietnamese Communist Party approved a "people's war" on the South at a session in January 1959, and, in May, Group 559 was established to maintain and upgrade the Ho Chi Minh trail, at this time a six-month mountain trek through Laos. On 28 July, North Vietnamese and Pathet Lao forces invaded Laos, fighting the Royal Lao Army all along the border. Group 559 was headquartered in Na Kai, Houaphan province in northeast Laos close to the border. About 500 of the "regroupees" of 1954 were sent south on the trail during its first year of operation. The first arms delivery via the trail was completed in August 1959. In April 1960, North Vietnam imposed universal military conscription for adult males. About 40,000 communist soldiers infiltrated the south from 1961 to 1963.

Kennedy's escalation, 1961–1963

In the 1960 U.S. presidential election, Senator

In the 1960 U.S. presidential election, Senator  Kennedy's policy toward South Vietnam assumed that Diệm and his forces had to ultimately defeat the guerrillas on their own. He was against the deployment of American combat troops and observed that "to introduce U.S. forces in large numbers there today, while it might have an initially favorable military impact, would almost certainly lead to adverse political and, in the long run, adverse military consequences." The quality of the South Vietnamese military, however, remained poor. Poor leadership, corruption, and political promotions all played a part in weakening the ARVN. The frequency of guerrilla attacks rose as the insurgency gathered steam. While Hanoi's support for the Viet Cong played a role, South Vietnamese governmental incompetence was at the core of the crisis.

One major issue Kennedy raised was whether the Soviet space and missile programs had surpassed those of the United States. Although Kennedy stressed long-range missile parity with the Soviets, he was also interested in using special forces for counterinsurgency warfare in Third World countries threatened by communist insurgencies. Although they were originally intended for use behind front lines after a conventional Soviet invasion of Europe, Kennedy believed that the guerrilla tactics employed by special forces such as the Special Forces (United States Army), Green Berets would be effective in a "brush fire" war in Vietnam.

Kennedy advisors Maxwell D. Taylor, Maxwell Taylor and Walt Rostow Taylor-Rostow Report, recommended that U.S. troops be sent to South Vietnam disguised as flood relief workers. Kennedy rejected the idea but increased military assistance yet again. In April 1962, John Kenneth Galbraith warned Kennedy of the "danger we shall replace the French as a colonial force in the area and bleed as the French did." Eisenhower's put 900 advisors in Vietnam, and by November 1963, Kennedy had put 16,000 American military personnel in Vietnam.

The Strategic Hamlet Program was initiated in late 1961. This joint U.S.–South Vietnamese program attempted to resettle the rural population into fortified villages. It was implemented in early 1962 and involved some forced relocation and segregation of rural South Vietnamese into new communities where the peasantry would be isolated from the Viet Cong. It was hoped these new communities would provide security for the peasants and strengthen the tie between them and the central government. However, by November 1963 the program had waned, and it officially ended in 1964.

On 23 July 1962, fourteen nations, including China, South Vietnam, the Soviet Union, North Vietnam and the United States, signed an International Agreement on the Neutrality of Laos, agreement promising to respect the neutrality of Laos.

Kennedy's policy toward South Vietnam assumed that Diệm and his forces had to ultimately defeat the guerrillas on their own. He was against the deployment of American combat troops and observed that "to introduce U.S. forces in large numbers there today, while it might have an initially favorable military impact, would almost certainly lead to adverse political and, in the long run, adverse military consequences." The quality of the South Vietnamese military, however, remained poor. Poor leadership, corruption, and political promotions all played a part in weakening the ARVN. The frequency of guerrilla attacks rose as the insurgency gathered steam. While Hanoi's support for the Viet Cong played a role, South Vietnamese governmental incompetence was at the core of the crisis.

One major issue Kennedy raised was whether the Soviet space and missile programs had surpassed those of the United States. Although Kennedy stressed long-range missile parity with the Soviets, he was also interested in using special forces for counterinsurgency warfare in Third World countries threatened by communist insurgencies. Although they were originally intended for use behind front lines after a conventional Soviet invasion of Europe, Kennedy believed that the guerrilla tactics employed by special forces such as the Special Forces (United States Army), Green Berets would be effective in a "brush fire" war in Vietnam.

Kennedy advisors Maxwell D. Taylor, Maxwell Taylor and Walt Rostow Taylor-Rostow Report, recommended that U.S. troops be sent to South Vietnam disguised as flood relief workers. Kennedy rejected the idea but increased military assistance yet again. In April 1962, John Kenneth Galbraith warned Kennedy of the "danger we shall replace the French as a colonial force in the area and bleed as the French did." Eisenhower's put 900 advisors in Vietnam, and by November 1963, Kennedy had put 16,000 American military personnel in Vietnam.

The Strategic Hamlet Program was initiated in late 1961. This joint U.S.–South Vietnamese program attempted to resettle the rural population into fortified villages. It was implemented in early 1962 and involved some forced relocation and segregation of rural South Vietnamese into new communities where the peasantry would be isolated from the Viet Cong. It was hoped these new communities would provide security for the peasants and strengthen the tie between them and the central government. However, by November 1963 the program had waned, and it officially ended in 1964.

On 23 July 1962, fourteen nations, including China, South Vietnam, the Soviet Union, North Vietnam and the United States, signed an International Agreement on the Neutrality of Laos, agreement promising to respect the neutrality of Laos.

Ousting and assassination of Ngô Đình Diệm

The inept performance of the ARVN was exemplified by failed actions such as the Battle of Ap Bac, Battle of Ấp Bắc on 2 January 1963, in which a small band of Viet Cong won a battle against a much larger and better-equipped South Vietnamese force, many of whose officers seemed reluctant even to engage in combat. During the battle the South Vietnamese had lost 83 soldiers and 5 US war helicopters serving to ferry ARVN troops that had been shot down by Vietcong forces, while the Vietcong forces had lost only 18 soldiers. The ARVN forces were led by Diệm's most trusted general, Huỳnh Văn Cao, commander of the IV Corps (South Vietnam), IV Corps. Cao was a Catholic who had been promoted due to religion and fidelity rather than skill, and his main job was to preserve his forces to stave off coup attempts; he had earlier vomited during a communist attack. Some policymakers in Washington began to conclude that Diệm was incapable of defeating the communists and might even make a deal with Ho Chi Minh. He seemed concerned only with fending off coups and had become more paranoid after attempts in 1960 and 1962, which he partly attributed to U.S. encouragement. As Robert F. Kennedy noted, "Diệm wouldn't make even the slightest concessions. He was difficult to reason with..." Historian James Gibson summed up the situation: Discontent with Diệm's policies exploded in May 1963 following the Huế Phật Đản shootings of nine unarmed Buddhists protesting against the ban on displaying the Buddhist flag on Vesak, the Buddha's birthday. This resulted in mass protests against discriminatory policies that gave privileges to the Catholic Church and its adherents over the Buddhist majority. Diệm's elder brother Pierre Martin Ngô Đình Thục, Ngô Đình Thục was the Archbishop of Huế and aggressively blurred the separation between church and state. Thuc's anniversary celebrations occurred shortly before Vesak had been bankrolled by the government, and Vatican flags were displayed prominently. There had also been reports of Catholic paramilitaries demolishing Buddhist pagodas throughout Diệm's rule. Diệm refused to make concessions to the Buddhist majority or take responsibility for the deaths. On 21 August 1963, the Army of the Republic of Vietnam Special Forces, ARVN Special Forces of Colonel Lê Quang Tung, loyal to Diệm's younger brother Ngô Đình Nhu, Xá Lợi Pagoda raids, raided pagodas across Vietnam, causing widespread damage and destruction and leaving a death toll estimated to range into the hundreds. U.S. officials began discussing the possibility of a regime change during the middle of 1963. The United States Department of State wanted to encourage a coup, while the Defense Department favored Diệm. Chief among the proposed changes was the removal of Diệm's younger brother Nhu, who controlled the secret police and special forces, and was seen as the man behind the Buddhist repression and more generally the architect of the Ngô family's rule. This proposal was conveyed to the U.S. embassy in Saigon in Cable 243.

U.S. officials began discussing the possibility of a regime change during the middle of 1963. The United States Department of State wanted to encourage a coup, while the Defense Department favored Diệm. Chief among the proposed changes was the removal of Diệm's younger brother Nhu, who controlled the secret police and special forces, and was seen as the man behind the Buddhist repression and more generally the architect of the Ngô family's rule. This proposal was conveyed to the U.S. embassy in Saigon in Cable 243.

The CIA contacted generals planning to remove Diệm and told them that the United States would not oppose such a move nor punish the generals by cutting off aid. President Diệm was overthrown and executed, along with his brother, on 2 November 1963. When Kennedy was informed, Maxwell Taylor remembered that he "rushed from the room with a look of shock and dismay on his face." Kennedy had not anticipated Diệm's murder. The U.S. ambassador to South Vietnam, Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., Henry Cabot Lodge, invited the coup leaders to the embassy and congratulated them. Ambassador Lodge informed Kennedy that "the prospects now are for a shorter war". Kennedy wrote Lodge a letter congratulating him for "a fine job".

Following the coup, chaos ensued. Hanoi took advantage of the situation and increased its support for the guerrillas. South Vietnam entered a period of extreme political instability, as one military government toppled another in quick succession. Increasingly, each new regime was viewed by the communists as a puppet of the Americans; whatever the failings of Diệm, his credentials as a nationalist (as Robert McNamara later reflected) had been impeccable.

U.S. military advisors were embedded at every level of the South Vietnamese armed forces. They were however criticized for ignoring the political nature of the insurgency. The Kennedy administration sought to refocus U.S. efforts on pacification- which in this case was defined as countering the growing threat of insurgency- and winning hearts and minds, "winning over the hearts and minds" of the population. The military leadership in Washington, however, was hostile to any role for U.S. advisors other than conventional troop training. General Paul D. Harkins, Paul Harkins, the COMUSMACV, commander of U.S. forces in South Vietnam, confidently predicted victory by Christmas 1963. The CIA was less optimistic, however, warning that "the Viet Cong by and large retain de facto control of much of the countryside and have steadily increased the overall intensity of the effort".

Paramilitary officers from the CIA's Special Activities Division trained and led Hmong people, Hmong tribesmen in Laos and into Vietnam. The indigenous forces numbered in the tens of thousands and they conducted direct action missions, led by paramilitary officers, against the Communist Pathet Lao forces and their North Vietnamese supporters. The CIA also ran the Phoenix Program and participated in Military Assistance Command, Vietnam – Studies and Observations Group (MAC-V SOG), which was originally named the Special Operations Group, but was changed for cover purposes.

The CIA contacted generals planning to remove Diệm and told them that the United States would not oppose such a move nor punish the generals by cutting off aid. President Diệm was overthrown and executed, along with his brother, on 2 November 1963. When Kennedy was informed, Maxwell Taylor remembered that he "rushed from the room with a look of shock and dismay on his face." Kennedy had not anticipated Diệm's murder. The U.S. ambassador to South Vietnam, Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., Henry Cabot Lodge, invited the coup leaders to the embassy and congratulated them. Ambassador Lodge informed Kennedy that "the prospects now are for a shorter war". Kennedy wrote Lodge a letter congratulating him for "a fine job".

Following the coup, chaos ensued. Hanoi took advantage of the situation and increased its support for the guerrillas. South Vietnam entered a period of extreme political instability, as one military government toppled another in quick succession. Increasingly, each new regime was viewed by the communists as a puppet of the Americans; whatever the failings of Diệm, his credentials as a nationalist (as Robert McNamara later reflected) had been impeccable.

U.S. military advisors were embedded at every level of the South Vietnamese armed forces. They were however criticized for ignoring the political nature of the insurgency. The Kennedy administration sought to refocus U.S. efforts on pacification- which in this case was defined as countering the growing threat of insurgency- and winning hearts and minds, "winning over the hearts and minds" of the population. The military leadership in Washington, however, was hostile to any role for U.S. advisors other than conventional troop training. General Paul D. Harkins, Paul Harkins, the COMUSMACV, commander of U.S. forces in South Vietnam, confidently predicted victory by Christmas 1963. The CIA was less optimistic, however, warning that "the Viet Cong by and large retain de facto control of much of the countryside and have steadily increased the overall intensity of the effort".

Paramilitary officers from the CIA's Special Activities Division trained and led Hmong people, Hmong tribesmen in Laos and into Vietnam. The indigenous forces numbered in the tens of thousands and they conducted direct action missions, led by paramilitary officers, against the Communist Pathet Lao forces and their North Vietnamese supporters. The CIA also ran the Phoenix Program and participated in Military Assistance Command, Vietnam – Studies and Observations Group (MAC-V SOG), which was originally named the Special Operations Group, but was changed for cover purposes.

Gulf of Tonkin and Johnson's escalation, 1963–1969

President Kennedy Assassination of John F. Kennedy, was assassinated on 22 November 1963. Vice PresidentGulf of Tonkin incident

On 2 August 1964, , on an intelligence mission along North Vietnam's coast, allegedly fired upon and damaged several torpedo boats that had been stalking it in the Gulf of Tonkin. A second attack was reported two days later on and ''Maddox'' in the same area. The circumstances of the attacks were murky. Lyndon Johnson commented to Undersecretary of State George Ball that "those sailors out there may have been shooting at flying fish." An undated National Security Agency, NSA publication declassified in 2005 revealed that there was no attack on 4 August. The second "attack" led to Operation Pierce Arrow, retaliatory airstrikes, and prompted Congress to approve the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution on 7 August 1964. The resolution granted the president power "to take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression" and Johnson would rely on this as giving him authority to expand the war. In the same month, Johnson pledged that he was not "committing American boys to fighting a war that I think ought to be fought by the boys of Asia to help protect their own land". The United States National Security Council, National Security Council recommended a three-stage escalation of the bombing of North Vietnam. Following an Attack on Camp Holloway, attack on a U.S. Army base in Pleiku on 7 February 1965, a series of airstrikes was initiated, Operation Flaming Dart, while Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin was on a state visit to North Vietnam. Operation Rolling Thunder and Operation Arc Light expanded aerial bombardment and ground support operations. The bombing campaign, which ultimately lasted three years, was intended to force North Vietnam to cease its support for the Viet Cong by threatening to destroy North Vietnamese air defenses and industrial infrastructure. It was additionally aimed at bolstering the morale of the South Vietnamese. Between March 1965 and November 1968, ''Rolling Thunder'' deluged the north with a million tons of missiles, rockets and bombs.

The United States National Security Council, National Security Council recommended a three-stage escalation of the bombing of North Vietnam. Following an Attack on Camp Holloway, attack on a U.S. Army base in Pleiku on 7 February 1965, a series of airstrikes was initiated, Operation Flaming Dart, while Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin was on a state visit to North Vietnam. Operation Rolling Thunder and Operation Arc Light expanded aerial bombardment and ground support operations. The bombing campaign, which ultimately lasted three years, was intended to force North Vietnam to cease its support for the Viet Cong by threatening to destroy North Vietnamese air defenses and industrial infrastructure. It was additionally aimed at bolstering the morale of the South Vietnamese. Between March 1965 and November 1968, ''Rolling Thunder'' deluged the north with a million tons of missiles, rockets and bombs.

Bombing of Laos

Bombing was not restricted to North Vietnam. Other aerial campaigns, such as Operation Barrel Roll, targeted different parts of the Viet Cong and PAVN infrastructure. These included the Ho Chi Minh trail supply route, which ran through Laos and Cambodia. The ostensibly neutral Laos had become Laotian Civil War, the scene of a civil war, pitting the Kingdom of Laos, Laotian government backed by the US against the Pathet Lao and its North Vietnamese allies. Massive aerial bombardment against the Pathet Lao and PAVN forces were carried out by the US to prevent the collapse of the Royal central government, and to deny the use of the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Between 1964 and 1973, the U.S. dropped two million tons of bombs on Laos, nearly equal to the 2.1 million tons of bombs the U.S. dropped on Europe and Asia during all of World War II, making Laos the most heavily bombed country in history relative to the size of its population. The objective of stopping North Vietnam and the Viet Cong was never reached. The Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force Curtis LeMay, however, had long advocated saturation bombing in Vietnam and wrote of the communists that "we're going to bomb them back into the Stone Age".The 1964 offensive

American ground war

On 8 March 1965, 3,500 United States Marine Corps, U.S. Marines were landed near Da Nang, South Vietnam. This marked the beginning of the American ground war. U.S. public opinion overwhelmingly supported the deployment. The Marines' initial assignment was the defense of Da Nang Air Base. The first deployment of 3,500 in March 1965 was increased to nearly 200,000 by December. The U.S. military had long been schooled in offensive warfare. Regardless of political policies, U.S. commanders were institutionally and psychologically unsuited to a defensive mission.

General William Westmoreland informed Admiral U. S. Grant Sharp Jr., commander of U.S. Pacific forces, that the situation was critical. He said, "I am convinced that U.S. troops with their energy, mobility, and firepower can successfully take the fight to the NLF (Viet Cong)". With this recommendation, Westmoreland was advocating an aggressive departure from America's defensive posture and the sidelining of the South Vietnamese. By ignoring ARVN units, the U.S. commitment became open-ended. Westmoreland outlined a three-point plan to win the war:

* Phase 1. Commitment of U.S. (and other free world) forces necessary to halt the losing trend by the end of 1965.

* Phase 2. U.S. and allied forces mount major offensive actions to seize the initiative to destroy guerrilla and organized enemy forces. This phase would end when the enemy had been worn down, thrown on the defensive, and driven back from major populated areas.

* Phase 3. If the enemy persisted, a period of twelve to eighteen months following Phase 2 would be required for the final destruction of enemy forces remaining in remote base areas.

On 8 March 1965, 3,500 United States Marine Corps, U.S. Marines were landed near Da Nang, South Vietnam. This marked the beginning of the American ground war. U.S. public opinion overwhelmingly supported the deployment. The Marines' initial assignment was the defense of Da Nang Air Base. The first deployment of 3,500 in March 1965 was increased to nearly 200,000 by December. The U.S. military had long been schooled in offensive warfare. Regardless of political policies, U.S. commanders were institutionally and psychologically unsuited to a defensive mission.

General William Westmoreland informed Admiral U. S. Grant Sharp Jr., commander of U.S. Pacific forces, that the situation was critical. He said, "I am convinced that U.S. troops with their energy, mobility, and firepower can successfully take the fight to the NLF (Viet Cong)". With this recommendation, Westmoreland was advocating an aggressive departure from America's defensive posture and the sidelining of the South Vietnamese. By ignoring ARVN units, the U.S. commitment became open-ended. Westmoreland outlined a three-point plan to win the war:

* Phase 1. Commitment of U.S. (and other free world) forces necessary to halt the losing trend by the end of 1965.

* Phase 2. U.S. and allied forces mount major offensive actions to seize the initiative to destroy guerrilla and organized enemy forces. This phase would end when the enemy had been worn down, thrown on the defensive, and driven back from major populated areas.

* Phase 3. If the enemy persisted, a period of twelve to eighteen months following Phase 2 would be required for the final destruction of enemy forces remaining in remote base areas.

The plan was approved by Johnson and marked a profound departure from the previous administration's insistence that the government of South Vietnam was responsible for defeating the guerrillas. Westmoreland predicted victory by the end of 1967. Johnson did not, however, communicate this change in strategy to the media. Instead he emphasized continuity. The change in U.S. policy depended on matching the North Vietnamese and the Viet Cong in a contest of attrition warfare, attrition and morale. The opponents were locked in a cycle of Conflict escalation, escalation. The idea that the government of South Vietnam could manage its own affairs was shelved. Westmoreland and McNamara furthermore touted the Body count#Vietnam War, body count system for gauging victory, a metric that would later prove to be flawed.

The American buildup transformed the South Vietnamese economy and had a profound effect on society. South Vietnam was inundated with manufactured goods. Stanley Karnow noted that "the main PX [Post Exchange], located in the Saigon suburb of Cholon, Ho Chi Minh City, Cholon, was only slightly smaller than the New York Bloomingdale's..."

The plan was approved by Johnson and marked a profound departure from the previous administration's insistence that the government of South Vietnam was responsible for defeating the guerrillas. Westmoreland predicted victory by the end of 1967. Johnson did not, however, communicate this change in strategy to the media. Instead he emphasized continuity. The change in U.S. policy depended on matching the North Vietnamese and the Viet Cong in a contest of attrition warfare, attrition and morale. The opponents were locked in a cycle of Conflict escalation, escalation. The idea that the government of South Vietnam could manage its own affairs was shelved. Westmoreland and McNamara furthermore touted the Body count#Vietnam War, body count system for gauging victory, a metric that would later prove to be flawed.

The American buildup transformed the South Vietnamese economy and had a profound effect on society. South Vietnam was inundated with manufactured goods. Stanley Karnow noted that "the main PX [Post Exchange], located in the Saigon suburb of Cholon, Ho Chi Minh City, Cholon, was only slightly smaller than the New York Bloomingdale's..."

Washington encouraged its Southeast Asia Treaty Organization, SEATO allies to contribute troops. Australia, New Zealand, Thailand and the Philippines all agreed to send troops. South Korea would later ask to join the Many Flags program in return for economic compensation. Major allies, however, notably NATO nations Canada and the United Kingdom, declined Washington's troop requests.

The U.S. and its allies mounted complex

Washington encouraged its Southeast Asia Treaty Organization, SEATO allies to contribute troops. Australia, New Zealand, Thailand and the Philippines all agreed to send troops. South Korea would later ask to join the Many Flags program in return for economic compensation. Major allies, however, notably NATO nations Canada and the United Kingdom, declined Washington's troop requests.

The U.S. and its allies mounted complex

The Johnson administration employed a "policy of minimum candor" in its dealings with the media. Military information officers sought to manage media coverage by emphasizing stories that portrayed progress in the war. Over time, this policy damaged the public trust in official pronouncements. As the media's coverage of the war and that of the Pentagon diverged, a so-called credibility gap developed. Despite Johnson and Westmoreland publicly proclaiming victory and Westmoreland stating that the "end is coming into view", internal reports in the ''Pentagon Papers'' indicate that Viet Cong forces retained strategic initiative and controlled their losses. Viet Cong attacks against static US positions accounted for 30% of all engagements, VC/PAVN ambushes and encirclements for 23%, American ambushes against Viet Cong/PAVN forces for 9%, and American forces attacking Viet Cong emplacements for only 5% of all engagements.

The Johnson administration employed a "policy of minimum candor" in its dealings with the media. Military information officers sought to manage media coverage by emphasizing stories that portrayed progress in the war. Over time, this policy damaged the public trust in official pronouncements. As the media's coverage of the war and that of the Pentagon diverged, a so-called credibility gap developed. Despite Johnson and Westmoreland publicly proclaiming victory and Westmoreland stating that the "end is coming into view", internal reports in the ''Pentagon Papers'' indicate that Viet Cong forces retained strategic initiative and controlled their losses. Viet Cong attacks against static US positions accounted for 30% of all engagements, VC/PAVN ambushes and encirclements for 23%, American ambushes against Viet Cong/PAVN forces for 9%, and American forces attacking Viet Cong emplacements for only 5% of all engagements.

Tet Offensive

In late 1967, the PAVN lured American forces into the hinterlands at Battle of Dak To, Đắk Tô and at the Marine Battle of Khe Sanh, Khe Sanh combat base in Quảng Trị Province, where the U.S. fought a series of battles known as The Hill Fights. These actions were part of a diversionary strategy meant to draw U.S. forces towards the Central Highlands. Preparations were underway for the ''General Offensive, General Uprising'', known as Tet Mau Than, or the

In late 1967, the PAVN lured American forces into the hinterlands at Battle of Dak To, Đắk Tô and at the Marine Battle of Khe Sanh, Khe Sanh combat base in Quảng Trị Province, where the U.S. fought a series of battles known as The Hill Fights. These actions were part of a diversionary strategy meant to draw U.S. forces towards the Central Highlands. Preparations were underway for the ''General Offensive, General Uprising'', known as Tet Mau Than, or the

During the first month of the offensive, 1,100 Americans and other allied troops, 2,100 ARVN and 14,000 civilians were killed. By the end of the first offensive, after two months, nearly 5,000 ARVN and over 4,000 U.S. forces had been killed and 45,820 wounded. The U.S. claimed 17,000 of the PAVN and Viet Cong had been killed and 15,000 wounded. A month later a second offensive known as the May Offensive was launched; although less widespread, it demonstrated the Viet Cong were still capable of carrying out orchestrated nationwide offensives. Two months later a third offensive was launched, the Phase III Offensive. The PAVN's own official records of their losses across all three offensives was 45,267 killed and 111,179 total casualties. By then it had become the bloodiest year of the war up to that point. The failure to spark a general uprising and the lack of defections among the ARVN units meant both war goals of Hanoi had fallen flat at enormous costs. By the end of 1968, the VC insurgents held almost no territory in South Vietnam, and their recruitment dropped by over 80%, signifying a drastic reduction in guerrilla operations, necessitating increased use of PAVN regular soldiers from the north.

Prior to Tet, in November 1967, Westmoreland had spearheaded a public relations drive for the Johnson administration to bolster flagging public support. In a speech before the National Press Club (USA), National Press Club he said a point in the war had been reached "where the end comes into view." Thus, the public was shocked and confused when Westmoreland's predictions were trumped by the Tet Offensive. Public approval of his overall performance dropped from 48 percent to 36 percent, and endorsement for the war effort fell from 40 percent to 26 percent." The American public and media began to turn against Johnson as the three offensives contradicted claims of progress made by the Johnson administration and the military.

At one point in 1968, Westmoreland considered the use of nuclear weapons in Vietnam in a contingency plan codenamed Fracture Jaw, which was abandoned when it became known to the White House. Westmoreland requested 200,000 additional troops, which was leaked to the media, and the subsequent fallout combined with intelligence failures caused him to be removed from command in March 1968, succeeded by his deputy Creighton Abrams.

During the first month of the offensive, 1,100 Americans and other allied troops, 2,100 ARVN and 14,000 civilians were killed. By the end of the first offensive, after two months, nearly 5,000 ARVN and over 4,000 U.S. forces had been killed and 45,820 wounded. The U.S. claimed 17,000 of the PAVN and Viet Cong had been killed and 15,000 wounded. A month later a second offensive known as the May Offensive was launched; although less widespread, it demonstrated the Viet Cong were still capable of carrying out orchestrated nationwide offensives. Two months later a third offensive was launched, the Phase III Offensive. The PAVN's own official records of their losses across all three offensives was 45,267 killed and 111,179 total casualties. By then it had become the bloodiest year of the war up to that point. The failure to spark a general uprising and the lack of defections among the ARVN units meant both war goals of Hanoi had fallen flat at enormous costs. By the end of 1968, the VC insurgents held almost no territory in South Vietnam, and their recruitment dropped by over 80%, signifying a drastic reduction in guerrilla operations, necessitating increased use of PAVN regular soldiers from the north.

Prior to Tet, in November 1967, Westmoreland had spearheaded a public relations drive for the Johnson administration to bolster flagging public support. In a speech before the National Press Club (USA), National Press Club he said a point in the war had been reached "where the end comes into view." Thus, the public was shocked and confused when Westmoreland's predictions were trumped by the Tet Offensive. Public approval of his overall performance dropped from 48 percent to 36 percent, and endorsement for the war effort fell from 40 percent to 26 percent." The American public and media began to turn against Johnson as the three offensives contradicted claims of progress made by the Johnson administration and the military.

At one point in 1968, Westmoreland considered the use of nuclear weapons in Vietnam in a contingency plan codenamed Fracture Jaw, which was abandoned when it became known to the White House. Westmoreland requested 200,000 additional troops, which was leaked to the media, and the subsequent fallout combined with intelligence failures caused him to be removed from command in March 1968, succeeded by his deputy Creighton Abrams.

On 10 May 1968, Paris Peace Accords, peace talks began between the United States and North Vietnam in Paris. Negotiations stagnated for five months, until Johnson gave orders to halt the bombing of North Vietnam. At the same time, Hanoi realized it could not achieve a "total victory" and employed a strategy known as "talking while fighting, fighting while talking", in which military offensives would occur concurrently with negotiations.

Johnson declined to run for re-election as his approval rating slumped from 48 to 36 percent. His escalation of the war in Vietnam divided Americans into warring camps, cost 30,000 American lives by that point and was regarded to have destroyed his presidency. Refusal to send more U.S. troops to Vietnam was also seen as Johnson's admission that the war was lost.''Command Magazine'' Issue 18, p. 15. As Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara noted, "the dangerous illusion of victory by the United States was therefore dead."

Vietnam was a major political issue during the 1968 United States presidential election, United States presidential election in 1968. The election was won by Republican party candidate Richard Nixon who claimed to have a secret plan to end the war.

On 10 May 1968, Paris Peace Accords, peace talks began between the United States and North Vietnam in Paris. Negotiations stagnated for five months, until Johnson gave orders to halt the bombing of North Vietnam. At the same time, Hanoi realized it could not achieve a "total victory" and employed a strategy known as "talking while fighting, fighting while talking", in which military offensives would occur concurrently with negotiations.

Johnson declined to run for re-election as his approval rating slumped from 48 to 36 percent. His escalation of the war in Vietnam divided Americans into warring camps, cost 30,000 American lives by that point and was regarded to have destroyed his presidency. Refusal to send more U.S. troops to Vietnam was also seen as Johnson's admission that the war was lost.''Command Magazine'' Issue 18, p. 15. As Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara noted, "the dangerous illusion of victory by the United States was therefore dead."

Vietnam was a major political issue during the 1968 United States presidential election, United States presidential election in 1968. The election was won by Republican party candidate Richard Nixon who claimed to have a secret plan to end the war.

Vietnamization, 1969–1972

Nuclear threats and diplomacy

U.S. president Richard Nixon began troop withdrawals in 1969. His plan to build up the ARVN so that it could take over the defense of South Vietnam became known as "Hanoi's war strategy

In September 1969, Ho Chi Minh died, aged seventy-nine. The failure of Tet in sparking a popular uprising caused a shift in Hanoi's war strategy, and the Võ Nguyên Giáp, Giáp-Trường Chinh, Chinh "Northern-First" faction regained control over military affairs from the Lê Duẩn-Hoàng Văn Thái "Southern-First" faction. An unconventional victory was sidelined in favor of a strategy built on conventional victory through conquest. Large-scale offensives were rolled back in favour of Low intensity conflict, small-unit and Sapper#PAVN and Viet Cong, sapper attacks as well as targeting the Hearts and Minds (Vietnam War), pacification and Vietnamization strategy. In the two-year period following Tet, the PAVN had begun its transformation from a fine Light infantry, light-infantry, limited mobility force into a Maneuver warfare, high-mobile and mechanised combined arms force. By 1970, over 70% of communist troops in the south were northerners, and southern-dominated VC units no longer existed.

In September 1969, Ho Chi Minh died, aged seventy-nine. The failure of Tet in sparking a popular uprising caused a shift in Hanoi's war strategy, and the Võ Nguyên Giáp, Giáp-Trường Chinh, Chinh "Northern-First" faction regained control over military affairs from the Lê Duẩn-Hoàng Văn Thái "Southern-First" faction. An unconventional victory was sidelined in favor of a strategy built on conventional victory through conquest. Large-scale offensives were rolled back in favour of Low intensity conflict, small-unit and Sapper#PAVN and Viet Cong, sapper attacks as well as targeting the Hearts and Minds (Vietnam War), pacification and Vietnamization strategy. In the two-year period following Tet, the PAVN had begun its transformation from a fine Light infantry, light-infantry, limited mobility force into a Maneuver warfare, high-mobile and mechanised combined arms force. By 1970, over 70% of communist troops in the south were northerners, and southern-dominated VC units no longer existed.

U.S. domestic controversies

The anti-war movement was gaining strength in the United States. Nixon appealed to the "silent majority" of Americans who he said supported the war without showing it in public. But revelations of the 1968 My Lai Massacre, in which a U.S. Army unit raped and killed civilians, and the 1969 "Green Beret Affair", where eight United States Army Special Forces, Special Forces soldiers, including the 5th Special Forces Group Commander, were arrested for the murder of a suspected double agent, provoked national and international outrage. In 1971, the ''Pentagon Papers'' were leaked to ''The New York Times''. The top-secret history of U.S. involvement in Vietnam, commissioned by the United States Department of Defense, Department of Defense, detailed a long series of public deceptions on the part of the U.S. government. The Supreme Court of the United States, Supreme Court ruled that its publication was legal.Collapsing U.S. morale

Following the Tet Offensive and the decreasing support among the U.S. public for the war, U.S. forces began a period of morale collapse, disillusionment and disobedience. At home, desertion rates quadrupled from 1966 levels. Among the enlisted, only 2.5% chose infantry combat positions in 1969–1970. Reserve Officers' Training Corps, ROTC enrollment decreased from 191,749 in 1966 to 72,459 by 1971, and reached an all-time low of 33,220 in 1974, depriving U.S. forces of much-needed military leadership. Open refusal to engage in patrols or carry out orders and disobedience began to emerge during this period, with one notable case of an entire company refusing orders to engage or carry out operations. Unit cohesion began to dissipate and focused on minimising contact with Viet Cong and PAVN. A practice known as "sand-bagging" started occurring, where units ordered to go on patrol would go into the country-side, find a site out of view from superiors and rest while radioing in false coordinates and unit reports. Drug usage increased rapidly among U.S. forces during this period, as 30% of U.S. troops regularly used marijuana, while a House subcommittee found 10–15% of U.S. troops in Vietnam regularly used high-grade heroin. From 1969 on, search-and-destroy operations became referred to as "search and evade" or "search and avoid" operations, falsifying battle reports while avoiding guerrilla fighters. A total of 900 fragging and suspected fragging incidents were investigated, most occurring between 1969 and 1971. In 1969, field-performance of the U.S. Forces was characterised by lowered morale, lack of motivation, and poor leadership. The significant decline in U.S. morale was demonstrated by the Battle of FSB Mary Ann in March 1971, in which a sapper attack inflicted serious losses on the U.S. defenders. William Westmoreland, no longer in command but tasked with investigation of the failure, cited a clear dereliction of duty, lax defensive postures and lack of officers in charge as its cause. On the collapse of U.S. morale, historian Shelby Stanton wrote:ARVN taking the lead and U.S. ground-force withdrawal

Beginning in 1970, American troops were withdrawn from border areas where most of the fighting took place and instead redeployed along the coast and interior. US casualties in 1970 were less than half of 1969 casualties after being relegated to less active combat. While U.S. forces were redeployed, the ARVN took over combat operations throughout the country, with casualties double US casualties in 1969, and more than triple US ones in 1970. In the post-Tet environment, membership in the South Vietnamese Regional Force and South Vietnamese Popular Force, Popular Force militias grew, and they were now more capable of providing village security, which the Americans had not accomplished under Westmoreland.

In 1970, Nixon announced the withdrawal of an additional 150,000 American troops, reducing the number of Americans to 265,500. By 1970, Viet Cong forces were no longer southern-majority, as nearly 70% of units were northerners. Between 1969 and 1971 the Viet Cong and some PAVN units had reverted to small unit tactics typical of 1967 and prior instead of nationwide grand offensives. In 1971, Australia and New Zealand withdrew their soldiers and U.S. troop count was further reduced to 196,700, with a deadline to remove another 45,000 troops by February 1972. The United States also reduced support troops, and in March 1971 the 5th Special Forces Group (United States), 5th Special Forces Group, the first American unit deployed to South Vietnam, withdrew to Fort Bragg, North Carolina.

Beginning in 1970, American troops were withdrawn from border areas where most of the fighting took place and instead redeployed along the coast and interior. US casualties in 1970 were less than half of 1969 casualties after being relegated to less active combat. While U.S. forces were redeployed, the ARVN took over combat operations throughout the country, with casualties double US casualties in 1969, and more than triple US ones in 1970. In the post-Tet environment, membership in the South Vietnamese Regional Force and South Vietnamese Popular Force, Popular Force militias grew, and they were now more capable of providing village security, which the Americans had not accomplished under Westmoreland.

In 1970, Nixon announced the withdrawal of an additional 150,000 American troops, reducing the number of Americans to 265,500. By 1970, Viet Cong forces were no longer southern-majority, as nearly 70% of units were northerners. Between 1969 and 1971 the Viet Cong and some PAVN units had reverted to small unit tactics typical of 1967 and prior instead of nationwide grand offensives. In 1971, Australia and New Zealand withdrew their soldiers and U.S. troop count was further reduced to 196,700, with a deadline to remove another 45,000 troops by February 1972. The United States also reduced support troops, and in March 1971 the 5th Special Forces Group (United States), 5th Special Forces Group, the first American unit deployed to South Vietnam, withdrew to Fort Bragg, North Carolina.

Cambodia

Prince

Prince Laos

Building up on the success of ARVN units in Cambodia, and further testing the Vietnamization program, the ARVN were tasked to launch Operation Lam Son 719 in February 1971, the first major ground operation aimed directly at attacking the Ho Chi Minh trail by attacking the major crossroad of Tchepone. This offensive would also be the first time the PAVN would field-test its combined arms force. The first few days were considered a success but the momentum had slowed after fierce resistance. Thiệu had halted the general advance, leaving armoured divisions able to surround them. Thieu had ordered air assault troops to capture Tchepone and withdraw, despite facing four-times larger numbers. During the withdrawal the PAVN counterattack had forced a panicked rout. Half of the ARVN troops involved were either captured or killed, half of the ARVN/US support helicopters were downed by anti-aircraft fire and the operation was considered a fiasco, demonstrating operational deficiencies still present within the ARVN. Nixon and Thieu had sought to use this event to show-case victory simply by capturing Tchepone, and it was spun off as an "operational success".

Building up on the success of ARVN units in Cambodia, and further testing the Vietnamization program, the ARVN were tasked to launch Operation Lam Son 719 in February 1971, the first major ground operation aimed directly at attacking the Ho Chi Minh trail by attacking the major crossroad of Tchepone. This offensive would also be the first time the PAVN would field-test its combined arms force. The first few days were considered a success but the momentum had slowed after fierce resistance. Thiệu had halted the general advance, leaving armoured divisions able to surround them. Thieu had ordered air assault troops to capture Tchepone and withdraw, despite facing four-times larger numbers. During the withdrawal the PAVN counterattack had forced a panicked rout. Half of the ARVN troops involved were either captured or killed, half of the ARVN/US support helicopters were downed by anti-aircraft fire and the operation was considered a fiasco, demonstrating operational deficiencies still present within the ARVN. Nixon and Thieu had sought to use this event to show-case victory simply by capturing Tchepone, and it was spun off as an "operational success".

Easter Offensive and Paris Peace Accords, 1972

Vietnamization was again tested by the Easter Offensive of 1972, a massive conventional PAVN invasion of South Vietnam. The PAVN quickly overran the northern provinces and in coordination with other forces attacked from Cambodia, threatening to cut the country in half. U.S. troop withdrawals continued, but American airpower responded, beginning Operation Linebacker, and the offensive was halted. The war was central to the 1972 United States presidential election, 1972 U.S. presidential election as Nixon's opponent, George McGovern, campaigned on immediate withdrawal. Nixon's National Security Advisor, Henry Kissinger, had continued secret negotiations with North Vietnam's Lê Đức Thọ and in October 1972 reached an agreement. President Thieu demanded changes to the peace accord upon its discovery, and when North Vietnam went public with the agreement's details, the Nixon administration claimed they were attempting to embarrass the president. The negotiations became deadlocked when Hanoi demanded new changes. To show his support for South Vietnam and force Hanoi back to the negotiating table, Nixon ordered Operation Linebacker II, a massive bombing of Hanoi and Haiphong 18–29 December 1972. Nixon pressured Thieu to accept the terms of the agreement or else face retaliatory military action from the U.S. On 15 January 1973, all U.S. combat activities were suspended. Lê Đức Thọ and Henry Kissinger, along with the PRG Foreign Minister Nguyễn Thị Bình and a reluctant President Thiệu, signed the Paris Peace Accords on 27 January 1973. This officially ended direct U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War, created a ceasefire between North Vietnam/PRG and South Vietnam, guaranteed the territorial integrity of Vietnam under the Geneva Conference of 1954, called for elections or a political settlement between the PRG and South Vietnam, allowed 200,000 communist troops to remain in the south, and agreed to a POW exchange. There was a sixty-day period for the total withdrawal of U.S. forces. "This article", noted Peter Church, "proved... to be the only one of the Paris Agreements which was fully carried out." All U.S. forces personnel were completely withdrawn by March 1973.U.S. exit and final campaigns, 1973–1975

In the lead-up to the ceasefire on 28 January, both sides attempted to maximize the land and population under their control in a campaign known as the War of the flags. Fighting continued after the ceasefire, this time without US participation, and continued throughout the year. North Vietnam was allowed to continue supplying troops in the South but only to the extent of replacing expended material. Later that year the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Kissinger and Thọ, but the North Vietnamese negotiator declined it saying that true peace did not yet exist. On 15 March 1973, Nixon implied the US would intervene again militarily if the North launched a full offensive, and Secretary of Defense James R. Schlesinger, James Schlesinger re-affirmed this position during his June 1973 confirmation hearings. Public and congressional reaction to Nixon's statement was unfavorable, prompting the U.S. Senate to pass the Case–Church Amendment to prohibit any intervention. PAVN/VC leaders expected the ceasefire terms would favor their side, but Saigon, bolstered by a surge of U.S. aid received just before the ceasefire went into effect, began to roll back the Viet Cong. The PAVN/VC responded with a new strategy hammered out in a series of meetings in Hanoi in March 1973, according to the memoirs of Trần Văn Trà. With U.S. bombings suspended, work on the Ho Chi Minh trail and other logistical structures could proceed unimpeded. Logistics would be upgraded until the North was in a position to launch a massive invasion of the South, projected for the 1975–1976 dry season. Tra calculated that this date would be Hanoi's last opportunity to strike before Saigon's army could be fully trained. The PAVN/VC resumed offensive operations when the dry season began in 1973, and by January 1974 had recaptured territory it lost during the previous dry season.

Within South Vietnam, the departure of the US military and the global recession that followed the 1973 oil crisis hurt an economy that was partly dependent on U.S. financial support and troop presence. After two clashes that left 55 ARVN soldiers dead, President Thieu announced on 4 January 1974, that the war had restarted and that the Paris Peace Accords were no longer in effect. There were over 25,000 South Vietnamese casualties during the ceasefire period. Gerald Ford took over as U.S. president on 9 August 1974 after the resignation of President Nixon, and Congress cut financial aid to South Vietnam from $1 billion a year to $700 million. Congress also voted in further restrictions on funding to be phased in through 1975 and to culminate in a total cutoff in 1976.

PAVN/VC leaders expected the ceasefire terms would favor their side, but Saigon, bolstered by a surge of U.S. aid received just before the ceasefire went into effect, began to roll back the Viet Cong. The PAVN/VC responded with a new strategy hammered out in a series of meetings in Hanoi in March 1973, according to the memoirs of Trần Văn Trà. With U.S. bombings suspended, work on the Ho Chi Minh trail and other logistical structures could proceed unimpeded. Logistics would be upgraded until the North was in a position to launch a massive invasion of the South, projected for the 1975–1976 dry season. Tra calculated that this date would be Hanoi's last opportunity to strike before Saigon's army could be fully trained. The PAVN/VC resumed offensive operations when the dry season began in 1973, and by January 1974 had recaptured territory it lost during the previous dry season.

Within South Vietnam, the departure of the US military and the global recession that followed the 1973 oil crisis hurt an economy that was partly dependent on U.S. financial support and troop presence. After two clashes that left 55 ARVN soldiers dead, President Thieu announced on 4 January 1974, that the war had restarted and that the Paris Peace Accords were no longer in effect. There were over 25,000 South Vietnamese casualties during the ceasefire period. Gerald Ford took over as U.S. president on 9 August 1974 after the resignation of President Nixon, and Congress cut financial aid to South Vietnam from $1 billion a year to $700 million. Congress also voted in further restrictions on funding to be phased in through 1975 and to culminate in a total cutoff in 1976.

The success of the 1973–1974 dry season offensive inspired Trà to return to Hanoi in October 1974 and plead for a larger offensive the next dry season. This time, Trà could travel on a drivable highway with regular fueling stops, a vast change from the days when the Ho Chi Minh trail was a dangerous mountain trek. Giáp, the North Vietnamese defence minister, was reluctant to approve of Trà's plan since a larger offensive might provoke U.S. reaction and interfere with the big push planned for 1976. Trà appealed to Giáp's superior, first secretary Lê Duẩn, who approved the operation. Trà's plan called for a limited offensive from Cambodia into Phước Long Province. The strike was designed to solve local logistical problems, gauge the reaction of South Vietnamese forces, and determine whether the U.S. would return.

The success of the 1973–1974 dry season offensive inspired Trà to return to Hanoi in October 1974 and plead for a larger offensive the next dry season. This time, Trà could travel on a drivable highway with regular fueling stops, a vast change from the days when the Ho Chi Minh trail was a dangerous mountain trek. Giáp, the North Vietnamese defence minister, was reluctant to approve of Trà's plan since a larger offensive might provoke U.S. reaction and interfere with the big push planned for 1976. Trà appealed to Giáp's superior, first secretary Lê Duẩn, who approved the operation. Trà's plan called for a limited offensive from Cambodia into Phước Long Province. The strike was designed to solve local logistical problems, gauge the reaction of South Vietnamese forces, and determine whether the U.S. would return.

On 13 December 1974, North Vietnamese forces Battle of Phuoc Long, attacked Phước Long. Phuoc Binh, the provincial capital, fell on 6 January 1975. Ford desperately asked Congress for funds to assist and re-supply the South before it was overrun. Congress refused. The fall of Phuoc Binh and the lack of an American response left the South Vietnamese elite demoralized.

The speed of this success led the Politburo to reassess its strategy. It decided that operations in the Central Highlands would be turned over to General Văn Tiến Dũng and that Pleiku should be seized, if possible. Before he left for the South, Dũng was addressed by Lê Duẩn: "Never have we had military and political conditions so perfect or a strategic advantage as great as we have now."

At the start of 1975, the South Vietnamese had three times as much artillery and twice the number of tanks and armoured cars as the PAVN. They also had 1,400 aircraft and a two-to-one numerical superiority in combat troops over the PAVN/VC. However, heightened oil prices meant that many of these assets could not be adequately leveraged. Moreover, the rushed nature of Vietnamization, intended to cover the US retreat, resulted in a lack of spare parts, ground-crew, and maintenance personnel, which rendered most of the equipment inoperable.

On 13 December 1974, North Vietnamese forces Battle of Phuoc Long, attacked Phước Long. Phuoc Binh, the provincial capital, fell on 6 January 1975. Ford desperately asked Congress for funds to assist and re-supply the South before it was overrun. Congress refused. The fall of Phuoc Binh and the lack of an American response left the South Vietnamese elite demoralized.

The speed of this success led the Politburo to reassess its strategy. It decided that operations in the Central Highlands would be turned over to General Văn Tiến Dũng and that Pleiku should be seized, if possible. Before he left for the South, Dũng was addressed by Lê Duẩn: "Never have we had military and political conditions so perfect or a strategic advantage as great as we have now."

At the start of 1975, the South Vietnamese had three times as much artillery and twice the number of tanks and armoured cars as the PAVN. They also had 1,400 aircraft and a two-to-one numerical superiority in combat troops over the PAVN/VC. However, heightened oil prices meant that many of these assets could not be adequately leveraged. Moreover, the rushed nature of Vietnamization, intended to cover the US retreat, resulted in a lack of spare parts, ground-crew, and maintenance personnel, which rendered most of the equipment inoperable.

Campaign 275

On 10 March 1975, General Dung launched Campaign 275, a limited offensive into the Central Highlands, supported by tanks and heavy artillery. The target was Battle of Buon Me Thuot, Buôn Ma Thuột, in Đắk Lắk Province. If the town could be taken, the provincial capital of Pleiku and the road to the coast would be exposed for a planned campaign in 1976. The ARVN proved incapable of resisting the onslaught, and its forces collapsed on 11 March. Once again, Hanoi was surprised by the speed of their success. Dung now urged the Politburo to allow him to seize Pleiku immediately and then turn his attention to Kon Tum. He argued that with two months of good weather remaining until the onset of the monsoon, it would be irresponsible to not take advantage of the situation. President Thiệu, a former general, was fearful that his forces would be cut off in the north by the attacking communists; Thieu ordered a retreat, which soon turned into a bloody rout. While the bulk of ARVN forces attempted to flee, isolated units fought desperately. ARVN general Phu abandoned Pleiku and Kon Tum and retreated toward the coast, in what became known as the "column of tears". On 20 March, Thieu reversed himself and ordered Huế, Vietnam's third-largest city, be held at all costs, and then changed his policy several times. As the PAVN launched their attack, panic set in, and ARVN resistance withered. On 22 March, the PAVN opened the siege of Huế. Civilians flooded the airport and the docks hoping for any mode of escape. As resistance in Huế collapsed, PAVN rockets rained down on Da Nang and its airport. By 28 March 35,000 PAVN troops were poised to attack the suburbs. By 30 March 100,000 leaderless ARVN troops surrendered as the PAVN marched victoriously through Da Nang. With the fall of the city, the defense of the Central Highlands and Northern provinces came to an end.Final North Vietnamese offensive

With the northern half of the country under their control, the Politburo ordered General Dung to launch the final offensive against Saigon. The operational plan for the Ho Chi Minh Campaign called for the capture of Saigon before 1 May. Hanoi wished to avoid the coming monsoon and prevent any redeployment of ARVN forces defending the capital. Northern forces, their morale boosted by their recent victories, rolled on, taking Nha Trang, Cam Ranh and Da Lat. On 7 April, three PAVN divisions attacked Battle of Xuân Lộc, Xuân Lộc, east of Saigon. For two bloody weeks, severe fighting raged as the ARVN defenders made a last stand to try to block the PAVN advance. On 21 April, however, the exhausted garrison was ordered to withdraw towards Saigon. An embittered and tearful president Thieu resigned on the same day, declaring that the United States had betrayed South Vietnam. In a scathing attack, he suggested that Kissinger had tricked him into signing the Paris peace agreement two years earlier, promising military aid that failed to materialize. Having transferred power to Trần Văn Hương on 21 April, he left for Taiwan on 25 April. After having appealed unsuccessfully to Congress for $722 million in emergency aid for South Vietnam, President Ford had given a televised speech on 23 April, declaring an end to the Vietnam War and all U.S. aid. By the end of April, the ARVN had collapsed on all fronts except in the Mekong Delta. Thousands of refugees streamed southward, ahead of the main communist onslaught. On 27 April, 100,000 PAVN troops encircled Saigon. The city was defended by about 30,000 ARVN troops. To hasten a collapse and foment panic, the PAVN shelled Tan Son Nhut Airport and forced its closure. With the air exit closed, large numbers of civilians found that they had no way out.Fall of Saigon

Chaos, unrest, and panic broke out as hysterical South Vietnamese officials and civilians scrambled to leave Saigon. Martial law was declared. American helicopters began evacuating South Vietnamese, U.S. and foreign nationals from various parts of the city and from the U.S. embassy compound. Operation Frequent Wind had been delayed until the last possible moment, because of U.S. Ambassador Graham Martin's belief that Saigon could be held and that a political settlement could be reached. Frequent Wind was the largest helicopter evacuation in history. It began on 29 April, in an atmosphere of desperation, as hysterical crowds of Vietnamese vied for limited space. Frequent Wind continued around the clock, as PAVN tanks breached defenses near Saigon. In the early morning hours of 30 April, the last U.S. Marines evacuated the embassy by helicopter, as civilians swamped the perimeter and poured into the grounds. On 30 April 1975, PAVN troops entered the city of Saigon and quickly overcame all resistance, capturing key buildings and installations. Two tanks from the 203rd Tank Brigade of the 2nd Corps (Vietnam), 2nd Corps crashed through the gates of the Independence Palace and the Viet Cong flag was raised above it at 11:30 am local time. President Dương Văn Minh, who had succeeded Huong two days earlier, surrendered to Lieutenant colonel Bùi Văn Tùng, the political commissar of the 203rd Tank Brigade. Minh was then escorted to Radio Saigon to announce the surrender declaration (spontaneously written by Tung). The statement was on air at 2:30 pm.Opposition to U.S. involvement

During the course of the Vietnam War a large segment of the American population came to be opposed to U.S. involvement in Southeast Asia. In January 1967, only 32% of Americans thought the U.S. had made a mistake in sending troops to Vietnam. Public opinion steadily turned against the war following 1967 and by 1970 only a third of Americans believed that the U.S. had not made a mistake by sending troops to fight in Vietnam.

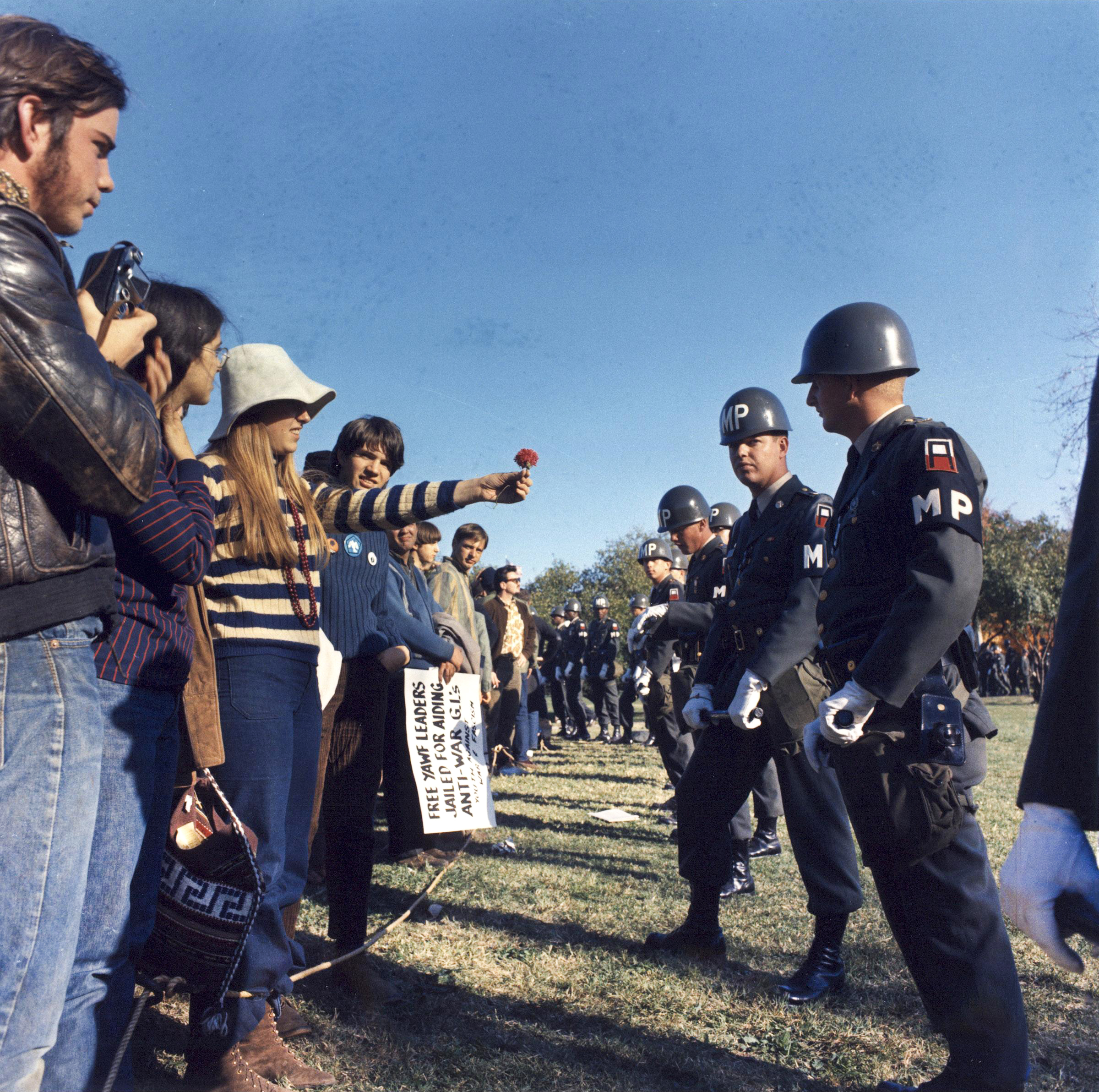

Early opposition to U.S. involvement in Vietnam drew its inspiration from the Geneva Conference of 1954. American support of Diệm in refusing elections was seen as thwarting the democracy America claimed to support. John F. Kennedy, while senator, opposed involvement in Vietnam. Nonetheless, it is possible to specify certain groups who led the anti-war movement at its peak in the late 1960s and the reasons why. Many young people protested because they were the ones being Conscription in the United States, drafted, while others were against the war because the anti-war movement grew increasingly popular among the counterculture of the 1960s, counterculture. Some advocates within the peace movement advocated a unilateral withdrawal of U.S. forces from Vietnam. Opposition to the Vietnam War tended to unite groups opposed to U.S. anti-communism and American imperialism, imperialism, and for those involved with the New Left, such as the Catholic Worker Movement. Others, such as Stephen Spiro, opposed the war based on the theory of Just War. Some wanted to show solidarity with the people of Vietnam, such as Norman Morrison emulating the self-immolation of Thích Quảng Đức.

High-profile opposition to the Vietnam War increasingly turned to mass protests in an effort to shift U.S. public opinion. Riots broke out at the 1968 Democratic National Convention during protests against the war. After news reports of American military abuses, such as the 1968 My Lai Massacre, brought new attention and support to the anti-war movement, some veterans joined Vietnam Veterans Against the War. On 15 October 1969, the Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam, Vietnam Moratorium attracted millions of Americans. The Kent State shootings, fatal shooting of four students at Kent State University in 1970 led to nationwide university protests. Anti-war protests declined after the signing of the

During the course of the Vietnam War a large segment of the American population came to be opposed to U.S. involvement in Southeast Asia. In January 1967, only 32% of Americans thought the U.S. had made a mistake in sending troops to Vietnam. Public opinion steadily turned against the war following 1967 and by 1970 only a third of Americans believed that the U.S. had not made a mistake by sending troops to fight in Vietnam.

Early opposition to U.S. involvement in Vietnam drew its inspiration from the Geneva Conference of 1954. American support of Diệm in refusing elections was seen as thwarting the democracy America claimed to support. John F. Kennedy, while senator, opposed involvement in Vietnam. Nonetheless, it is possible to specify certain groups who led the anti-war movement at its peak in the late 1960s and the reasons why. Many young people protested because they were the ones being Conscription in the United States, drafted, while others were against the war because the anti-war movement grew increasingly popular among the counterculture of the 1960s, counterculture. Some advocates within the peace movement advocated a unilateral withdrawal of U.S. forces from Vietnam. Opposition to the Vietnam War tended to unite groups opposed to U.S. anti-communism and American imperialism, imperialism, and for those involved with the New Left, such as the Catholic Worker Movement. Others, such as Stephen Spiro, opposed the war based on the theory of Just War. Some wanted to show solidarity with the people of Vietnam, such as Norman Morrison emulating the self-immolation of Thích Quảng Đức.

High-profile opposition to the Vietnam War increasingly turned to mass protests in an effort to shift U.S. public opinion. Riots broke out at the 1968 Democratic National Convention during protests against the war. After news reports of American military abuses, such as the 1968 My Lai Massacre, brought new attention and support to the anti-war movement, some veterans joined Vietnam Veterans Against the War. On 15 October 1969, the Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam, Vietnam Moratorium attracted millions of Americans. The Kent State shootings, fatal shooting of four students at Kent State University in 1970 led to nationwide university protests. Anti-war protests declined after the signing of the Involvement of other countries

Pro-Hanoi

China

The People's Republic of China provided significant support for North Vietnam when the U.S. started to intervene, included through financial aid and the deployment of hundreds of thousands of military personnel in support roles. China said that its military and economic aid to North Vietnam and the Viet Cong totaled $20 billion (approx. $160 billion adjusted for inflation in 2022) during the Vietnam War; included in that aid were donations of 5 million tons of food to North Vietnam (equivalent to North Vietnamese food production in a single year), accounting for 10–15% of the North Vietnamese food supply by the 1970s. In the summer of 1962, Mao Zedong agreed to supply Hanoi with 90,000 rifles and guns free of charge, and starting in 1965, China began sending Anti-aircraft warfare, anti-aircraft units and engineering battalions to North Vietnam to repair the damage caused by American bombing. In particular, they helped man anti-aircraft batteries, rebuild roads and railroads, transport supplies, and perform other engineering works. This freed North Vietnamese army units for combat in the South. China sent 320,000 troops and annual arms shipments worth $180 million. The Chinese military claims to have caused 38% of American air losses in the war. The PRC also began financing the Khmer Rouge as a counterweight to North Vietnam at this time. China "armed and trained" the Khmer Rouge during the civil war, and continued to aid them for years afterward.Soviet Union

The

The Pro-Saigon