Valentine Lawless, 2nd Baron Cloncurry on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Valentine Brown Lawless, 2nd Baron Cloncurry (19 August 1773 – 28 October 1853), was an Irish

Lawless returned in 1804 to oversee Sir Richard Morrison's £200,000 refurbishment of Lyons House (equivalent to €15.25m today) and the reorganisation of his extensive estates. He employed the Italian painter Gaspare Gabrielli to paint the

Lawless returned in 1804 to oversee Sir Richard Morrison's £200,000 refurbishment of Lyons House (equivalent to €15.25m today) and the reorganisation of his extensive estates. He employed the Italian painter Gaspare Gabrielli to paint the

In 1807 Lawless brought a sensational action for

In 1807 Lawless brought a sensational action for

Personal recollections of the life and times, with extracts from the correspondence of Valentine Lord Cloncurry

', Dublin: J. McGlashan; London: W.S. Orr, 1849.

* Linebaugh, Peter; Rediker, Marcus,''The Many-Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners, and the Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic''. Boston: Beacon Press. (2000) . * * * ''Annals of Ardclough'' by

peer

Peer may refer to:

Sociology

* Peer, an equal in age, education or social class; see Peer group

* Peer, a member of the peerage; related to the term "peer of the realm"

Computing

* Peer, one of several functional units in the same layer of a ne ...

, politician and landowner. In the 1790s he was an emissary in radical and reform circles in London for the Society of United Irishmen

The Society of United Irishmen was a sworn association in the Kingdom of Ireland formed in the wake of the French Revolution to secure "an equal representation of all the people" in a national government. Despairing of constitutional reform, ...

, and was twice detained on suspicion of sedition. He gained notoriety for his celebrated lawsuit for adultery

Adultery (from Latin ''adulterium'') is extramarital sex that is considered objectionable on social, religious, moral, or legal grounds. Although the sexual activities that constitute adultery vary, as well as the social, religious, and legal ...

against his former friend Sir John Piers, who had seduced Cloncurry's first wife, Elizabeth Georgiana Morgan. He took up residence at Lyons Hill, Ardclough, County Kildare

County Kildare ( ga, Contae Chill Dara) is a county in Ireland. It is in the province of Leinster and is part of the Eastern and Midland Region. It is named after the town of Kildare. Kildare County Council is the local authority for the count ...

and, commensurate with his status as an Anglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish people () denotes an ethnic, social and religious grouping who are mostly the descendants and successors of the English Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. They mostly belong to the Anglican Church of Ireland, which was the establis ...

lord, appeared to reconcile to the Dublin authorities. Lawless served as a Viceregal advisor and eventually gained a British peerage

The peerages in the United Kingdom are a legal system comprising both hereditary and lifetime titles, composed of various noble ranks, and forming a constituent part of the British honours system. The term '' peerage'' can be used both c ...

, but it was not as an Ascendancy loyalist. He pressed the case for admitting Catholics to parliament and for ending the universal imposition of Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland ( ga, Eaglais na hÉireann, ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Kirk o Airlann, ) is a Christian church in Ireland and an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. It is organised on an all-Ireland basis and is the sec ...

tithe

A tithe (; from Old English: ''teogoþa'' "tenth") is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government. Today, tithes are normally voluntary and paid in cash or cheques or more ...

s.

Family and education

Lawless was born inMerrion Square

Merrion Square () is a Georgian garden square on the southside of Dublin city centre.

History

The square was laid out in 1752 by the estate of Viscount FitzWilliam and was largely complete by the beginning of the 19th century. The demand f ...

in Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 ...

. His father, Nicholas Lawless, son of the Dublin merchant Robert Lawless, who Lawless recounts was "one of the many Irish Roman Catholics" who sought, in France, the "liberty to enjoy those privileges of property and talent from which they were debarred nder the Penal Lawsin their native land". He purchased an estate near Rouen

Rouen (, ; or ) is a city on the River Seine in northern France. It is the prefecture of the region of Normandy and the department of Seine-Maritime. Formerly one of the largest and most prosperous cities of medieval Europe, the population ...

; but finding that in France the Catholic Church "made invidious distinctions in the distribution of her honours among the faithful", not only returned to Ireland but conformed to the established Anglican communion

The Anglican Communion is the third largest Christian communion after the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches. Founded in 1867 in London, the communion has more than 85 million members within the Church of England and other ...

. A successful wool merchant and banker, Nicholas Lawless was created a baronet

A baronet ( or ; abbreviated Bart or Bt) or the female equivalent, a baronetess (, , or ; abbreviation Btss), is the holder of a baronetcy, a hereditary title awarded by the British Crown. The title of baronet is mentioned as early as the 14t ...

in 1776 and elevated to the peerage as Baron Cloncurry in 1789. Valentine's mother was Margaret Browne, only daughter and heiress of Valentine Browne of Mount Browne, County Limerick

"Remember Limerick"

, image_map = Island_of_Ireland_location_map_Limerick.svg

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Republic of Ireland, Ireland

, subdivision_type1 = Provinces of Ireland, Province

, subd ...

; she died in 1795. The family lived mainly at Maretimo House, Blackrock, County Dublin

Blackrock () is a suburb of Dublin, Ireland, northwest of Dún Laoghaire.

Location and access

Blackrock covers a large but not precisely defined area, rising from sea level on the coast to at White's Cross on the N11 national primary ro ...

, which Nicholas had built around 1770.

At the age of 12 years he was placed at the school of the Rev. Dr. Burrowes, at Prospect, Blackrock: "not then sent", he remarked, like many of his class "to learn absenteeism and contempt, too often hatred, for our country, in the schools and colleges of England." With a view to preparing him for Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, he was briefly enrolled King's School, Chester, but prevailed on his father to let him study in his "native city". In 1792, Lawless graduated with a bachelor in arts from Trinity College, Dublin

, name_Latin = Collegium Sanctae et Individuae Trinitatis Reginae Elizabethae juxta Dublin

, motto = ''Perpetuis futuris temporibus duraturam'' (Latin)

, motto_lang = la

, motto_English = It will last i ...

. While at Trinity he was active in the Historical Society

A historical society (sometimes also preservation society) is an organization dedicated to preserving, collecting, researching, and interpreting historical information or items. Originally, these societies were created as a way to help future g ...

, the club formed by Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS">New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS/nowiki>_1729_–_9_July_1797)_was_an_NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">N ...

, in which, preceding Lawless, the future United Irishmen Wolfe Tone

Theobald Wolfe Tone, posthumously known as Wolfe Tone ( ga, Bhulbh Teón; 20 June 176319 November 1798), was a leading Irish revolutionary figure and one of the founding members in Belfast and Dublin of the United Irishmen, a republican socie ...

and Thomas Addis Emmet had engaged in their first debates. He then spent two years in Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

.

Lawless was to write that while he "left Ireland with a mind freely sown with the seeds of love of country and nationality, and hatred of the oppressions imposed upon the Irish masses by the oligarchy into whose hands the legislative power had fallen", he returned "more Irish than ever". Among the French emigres he encountered in Switzerland, were officers of the Irish Brigade. While he little sympathises with "the cause of royalty" for which they had suffered, he was moved by the tales of the betrayal and dispossession that, following the Williamite War in Ireland

The Williamite War in Ireland (1688–1691; ga, Cogadh an Dá Rí, "war of the two kings"), was a conflict between Jacobite supporters of deposed monarch James II and Williamite supporters of his successor, William III. It is also called th ...

, had forced their fathers to seek fortune abroad.

Revolutionary career

Lawless returned to Ireland in the spring of 1795 after hopes of reform had been dashed by the recall of William Fitzwilliam who,Lord Lieutenant

A lord-lieutenant ( ) is the British monarch's personal representative in each lieutenancy area of the United Kingdom. Historically, each lieutenant was responsible for organising the county's militia. In 1871, the lieutenant's responsibilit ...

, had spoken in favour of Catholic Emancipation

Catholic emancipation or Catholic relief was a process in the kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland, and later the combined United Kingdom in the late 18th century and early 19th century, that involved reducing and removing many of the restricti ...

. In June 1795, Lawless was sworn into the Dublin Society of United Irishman. According to his own account, he took the Society's original—as he saw it, pre-republican— membership test. Composed by William Drennan

William Drennan (23 May 1754 – 5 February 1820) was an Irish physician and writer who moved the formation in Belfast and Dublin of the Society of United Irishmen. He was the author of the Society's original "test" which, in the cause of ...

, this committed Lawless to forward a "union of power among Irishmen of every religious" so as to attain "an impartial and adequate representation of the Irish nation in parliament". Reflecting the growing impatience and insurrectionary tenor of the movement, a convention in Belfast had, the previous month, adopted amendments dropping the reference to the Irish Parliament and swearing members to secrecy.

Lawless played an open, constitutionalist, role, publicly protesting what he knew to be Prime Minister William Pitt's undeclared Irish policy: the abolition of the Dublin parliament and the incorporation of Ireland into a united kingdom with Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It ...

. In the spring of 1797, he wrote and published his ''Thoughts on the Projected Union between Great Britain and Ireland'', the first of a long succession of pamphlets on the subject. He was also a regular contributor to the paper of the Dublin Society of United Irishmen, ''The Press.'' On the dissolution of parliament in 1797, he tried to persuade Lord Edward Fitzgerald

Lord Edward FitzGerald (15 October 1763 – 4 June 1798) was an Irish aristocrat who abandoned his prospects as a distinguished veteran of British service in the American War of Independence, and as an Irish Parliamentarian, to embrace the caus ...

to stand, as he had in 1790, for Kildare

Kildare () is a town in County Kildare, Ireland. , its population was 8,634 making it the 7th largest town in County Kildare. The town lies on the R445, some west of Dublin – near enough for it to have become, despite being a regional ce ...

as Patriot and to oppose a union. He also presided over a large anti-union protest meeting at the Royal Exchange. But then, with Fitzgerald, Lawless began attending the United Irish executive in Dublin which increasingly turned to preparations for a French-assisted insurrection.

Lawless personally administered the society's new test to Father James Coigly, who was to be the executive principal agent in attempts to coordinate an insurrection with radical circles in England and with the French directory

The Directory (also called Directorate, ) was the governing five-member committee in the French First Republic from 2 November 1795 until 9 November 1799, when it was overthrown by Napoleon Bonaparte in the Coup of 18 Brumaire and replaced b ...

. Valentine, himself, seconded Cogly efforts in London where he is known to have been in contact with Edward Despard

Edward Marcus Despard (175121 February 1803), an Kingdom of Ireland, Irish officer in the service of the The Crown, British Crown, gained notoriety as a colonial administrator for refusing to recognise racial distinctions in law and, following his ...

who, in 1803, was to hang as the alleged ringleader in a plot to assassinate the king.

At the end of February 1798 Coigly was arrested with Arthur O'Connor and three others seeking a Channel

Channel, channels, channeling, etc., may refer to:

Geography

* Channel (geography), in physical geography, a landform consisting of the outline (banks) of the path of a narrow body of water.

Australia

* Channel Country, region of outback Austral ...

crossing in Margate

Margate is a seaside resort, seaside town on the north coast of Kent in south-east England. The town is estimated to be 1.5 miles long, north-east of Canterbury and includes Cliftonville, Garlinge, Palm Bay, UK, Palm Bay and Westbrook, Kent, ...

. Coigly, carrying an address from the "United Britons" to the Directory in Paris, was convicted of treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

and hanged. In furnishing funds for Coigly's defence, Lawless heightened the suspicion with which he was regarded by the authorities. On 31 May 1798, he was arrested at his London lodgings and was committed to the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is separa ...

where he was held, without charge, until March 1801. It was widely believed that his long imprisonment hastened his father's death in August 1799.

Paris and Rome

On his release, Lawless went toParis

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

and then Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

, where he met and married his first wife, Elizabeth Gergiana Morgan, daughter of General Charles Morgan. It was an impulsive love marriage to a "woman he adored", but which he later came to regret as "hasty and imprudent". He was in Rome during Robert Emmet

Robert Emmet (4 March 177820 September 1803) was an Irish Republican, orator and rebel leader. Following the suppression of the United Irish uprising in 1798, he sought to organise a renewed attempt to overthrow the British Crown and Protes ...

's rebellion and is believed by Emmet's biographer Ruan O’Donnell to have been a member of the new Republican Government in waiting. Lawless used his time in Rome to purchase works of art being sold off by Italian nobles under pressure from Napoleon's

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

oppressive taxation, and sent four shiploads to Ireland for the refurbishment of Lyons House. They included a statue of Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is sometimes called Earth's "sister" or "twin" planet as it is almost as large and has a similar composition. As an interior planet to Earth, Venus (like Mercury) appears in Earth's sky never fa ...

excavated at Ostia and three pillars from the palace of Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68), was the fifth Roman emperor and final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 un ...

originally looted from Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

, but other artefacts were lost when the third shipment sank off Wicklow Head

Wicklow Head () is a headland near the southeast edge of the town of Wicklow in County Wicklow, approximately from the centre of the town.

Geographically, it is the easternmost point on the mainland of the Republic of Ireland.

Lighthouses

The ...

.

Lyons House

Lawless returned in 1804 to oversee Sir Richard Morrison's £200,000 refurbishment of Lyons House (equivalent to €15.25m today) and the reorganisation of his extensive estates. He employed the Italian painter Gaspare Gabrielli to paint the

Lawless returned in 1804 to oversee Sir Richard Morrison's £200,000 refurbishment of Lyons House (equivalent to €15.25m today) and the reorganisation of his extensive estates. He employed the Italian painter Gaspare Gabrielli to paint the frescoes

Fresco (plural ''frescos'' or ''frescoes'') is a technique of mural painting executed upon freshly laid ("wet") lime plaster. Water is used as the vehicle for the dry-powder pigment to merge with the plaster, and with the setting of the plaste ...

, a fact which assumed great significance during his subsequent action against Sir John Piers for adultery.Malcolmson p.151

At Lyons, Lawless hosted Catherine Despard

Catherine Despard (died 1815), from Jamaica, publicised political detentions and prison conditions in London where her Irish husband, Colonel Edward Despard, was repeatedly incarcerated for their shared democratic convictions. Her extensive lobbyi ...

, possibly at the request of Sir Francis Burdett

Sir Francis Burdett, 5th Baronet (25 January 1770 – 23 January 1844) was a British politician and Member of Parliament who gained notoriety as a proponent (in advance of the Chartists) of universal male suffrage, equal electoral districts, vo ...

who had helped secure her a pension following the execution of her husband, Captain Edward Despard, for treason (the Despard Plot

The Despard Plot was a failed 1802 conspiracy by British revolutionaries led by Colonel Edward Marcus Despard, a former army officer and colonial official. Evidence presented in court suggested that Despard planned to assassinate the monarch Ge ...

) in 1803.

Divorce and remarriage

In 1807 Lawless brought a sensational action for

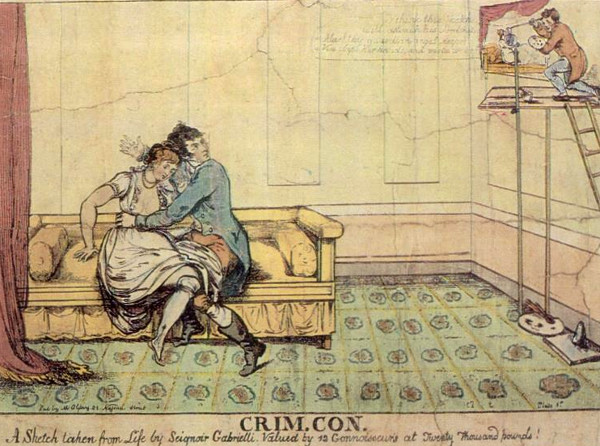

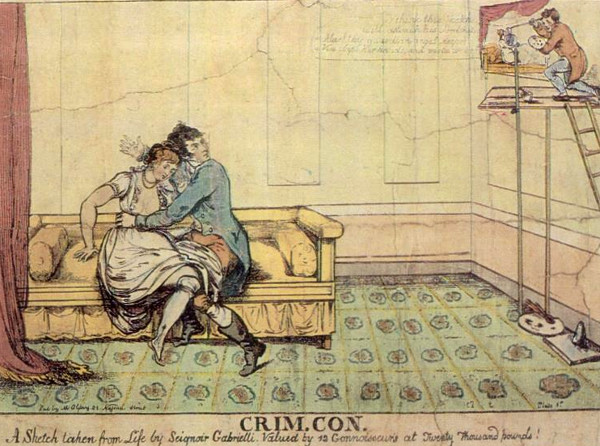

In 1807 Lawless brought a sensational action for criminal conversation

At common law, criminal conversation, often abbreviated as ''crim. con.'', is a tort arising from adultery. "Conversation" is an old euphemism for sexual intercourse that is obsolete except as part of this term.

It is similar to breach of p ...

against Sir John Bennett Piers, 6th Baronet

Sir John Bennett Piers, 6th Baronet, of Tristernagh Abbey, (1772 – 22 July 1845) was an Anglo-Irish baronet, now mainly remembered for his part in the Cloncurry case, an adultery scandal of the early 19th century, and for being the subject of ...

, a neighbour and school friend,Howlin p.87 whose dalliance with Lady Cloncurry had been witnessed by the painter Gaspare Gabrielli while he was at work painting frescoes at Lyons House. The lurid details of the case aroused huge public interest, in particular the barely credible evidence that the couple had been too preoccupied to notice that the painter was up a ladder in the same room. Lawless first became suspicious when he saw his wife and Piers walking hand in hand: he confronted his wife who broke down and confessed. Piers did not contest the action, having fled to the Isle of Man

)

, anthem = "O Land of Our Birth"

, image = Isle of Man by Sentinel-2.jpg

, image_map = Europe-Isle_of_Man.svg

, mapsize =

, map_alt = Location of the Isle of Man in Europe

, map_caption = Location of the Isle of Man (green)

in Europe ...

, where he remained for some years.

Lawless was awarded the then enormous sum of £20,000 in damages, although it was many years before he actually saw the money. As usual the action was the prelude to a divorce

Divorce (also known as dissolution of marriage) is the process of terminating a marriage or marital union. Divorce usually entails the canceling or reorganizing of the legal duties and responsibilities of marriage, thus dissolving the ...

from his wife, which he obtained by a private Act of Parliament

Proposed bills are often categorized into public bills and private bills. A public bill is a proposed law which would apply to everyone within its jurisdiction. This is unlike a private bill which is a proposal for a law affecting only a single p ...

in 1811. They had a son, Valentine, who died young, and a daughter, Mary, who married firstly Henry Fock, 3rd Baron De Robeck

Baron de Robeck is a title of the head of the Irish Fock family which has its origins in Sweden. Jakob Constantin Fock, a Swedish landowner, had bought the Räbäck estate in the parish of Medelplana, Skaraborg County in the province of Västergö ...

, by whom she had three children. Like her parents, her marriage ended in divorce by Act of Parliament. She married secondly in 1828 Lord Sussex Lennox

Lord Sussex Lennox (11 June 1802 – 12 April 1874) was an English cricketer. He was associated with Marylebone Cricket Club and was recorded in one first-class match in 1826, totalling 5 runs with a highest score of 3 and holding no catches. ...

, by whom she had three further children.

Elizabeth had a second son, born in 1807, who was generally believed to have been fathered by Sir John Piers. Lady Cloncurry was the youngest daughter of General Charles Morgan, Commander-in-Chief, India

During the period of the Company rule in India and the British Raj, the Commander-in-Chief, India (often "Commander-in-Chief ''in'' or ''of'' India") was the supreme commander of the British Indian Army. The Commander-in-Chief and most of his ...

, and his wife Hannah Wagstaff, daughter of William Wagstaff of Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

. After returning to live with her father for some years, she went to Italy, where she remarried the Rev John Sandford, the absentee vicar of Nynehead

Nynehead is a village and civil parish in Somerset, England, situated on the River Tone, south-west of Taunton and north-west of Wellington, in the Somerset West and Taunton district. The village has a population of 415.

History

The first d ...

, Somerset

( en, All The People of Somerset)

, locator_map =

, coordinates =

, region = South West England

, established_date = Ancient

, established_by =

, preceded_by =

, origin =

, lord_lieutenant_office =Lord Lieutenant of Somerset

, lord_ ...

, in 1819, and died in 1857. She and Sandford had one daughter Anna, who married Frederick Methuen, 2nd Baron Methuen

Frederick Henry Paul Methuen, 2nd Baron Methuen (23 February 1818 – 26 September 1891), was a British peer and Liberal politician.

Methuen was the son of Paul Methuen, 1st Baron Methuen, and his wife Jane Dorothea (née St John-Mildmay). He ...

.

Her former husband remarried in 1811 Emily Douglas, third daughter of Archibald Douglas and Mary Crosbie, and widow of the Hon. Joseph Leeson, by whom she was the mother of Joseph Leeson, 4th Earl of Milltown Joseph Leeson, 4th Earl of Milltown KP (11 February 1799 – 31 January 1866) was an Anglo-Irish peer, styled Viscount Russborough from 1801 to 1807.

He was the son of the Hon. Joseph Leeson, who died shortly after his birth, and Emily Douglas, t ...

. They had three more children, including Edward, 3rd Baron Cloncurry. Emily died in 1841: her husband in his memoir paid loving tribute to their thirty years of uninterrupted happiness.

Viceregal Advisor

From 1811 Lawless championedCatholic Emancipation

Catholic emancipation or Catholic relief was a process in the kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland, and later the combined United Kingdom in the late 18th century and early 19th century, that involved reducing and removing many of the restricti ...

and later urged O’Connell to prioritise repeal of the Act of Union. But not wishing to compromise his friendship with Henry Paget, 1st Marquess of Anglesey

Henry William Paget, 1st Marquess of Anglesey (17 May 1768 – 29 April 1854), styled Lord Paget between 1784 and 1812 and known as the Earl of Uxbridge between 1812 and 1815, was a British Army officer and politician. After serving as a member ...

, the new Lord Lieutenant

A lord-lieutenant ( ) is the British monarch's personal representative in each lieutenancy area of the United Kingdom. Historically, each lieutenant was responsible for organising the county's militia. In 1871, the lieutenant's responsibilit ...

, he was steadfast in not aligning himself publicly with O’Connell. After 1828 he became a member of the Anglesey's private cabinet and kept horses ready at Lyons for impromptu meetings with the viceroy both from 1828 to 1829 (when Anglesey was popular), and from 1830 to 1834 (when he was not). Dublin Castle

Dublin Castle ( ga, Caisleán Bhaile Átha Cliath) is a former Motte-and-bailey castle and current Irish government complex and conference centre. It was chosen for its position at the highest point of central Dublin.

Until 1922 it was the se ...

remained suspicious, however. In 1829 Daniel O’Connell stated that the Lord Lieutenant had been recalled to London "because he visited Lord Cloncurry".Dunlop p.247

Lawless ran for parliament but remained prominent as a magistrate (he helped introduce public petty sessions in Kildare to make the legal system more accessible to the people) and as a "tithe abolitionist". He spoke out on the "partial and oppressive" nature of forcible tithe collection for the Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland ( ga, Eaglais na hÉireann, ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Kirk o Airlann, ) is a Christian church in Ireland and an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. It is organised on an all-Ireland basis and is the sec ...

in the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the Bicameralism, upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by Life peer, appointment, Hereditary peer, heredity or Lords Spiritual, official function. Like the ...

in December 1831. By then, shortly after the death of William IV

William IV (William Henry; 21 August 1765 – 20 June 1837) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from 26 June 1830 until his death in 1837. The third son of George III, William succeeded h ...

, he had been admitted to the privy council and had been created the second Baron Cloncurry in the British peerage.

Death and reputation

His health began to fail in 1851. He died at the older family home, Maretimo House, Blackrock, on 28 October 1853, and was buried in the familyvault

Vault may refer to:

* Jumping, the act of propelling oneself upwards

Architecture

* Vault (architecture), an arched form above an enclosed space

* Bank vault, a reinforced room or compartment where valuables are stored

* Burial vault (enclosure ...

at Lyons Hill. The title passed to his eldest surviving son Edward, who committed suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders), physical disorders (such as chronic fatigue syndrome), and s ...

in 1869 by throwing himself out of a third-floor window at Lyons Hill.

Daniel O'Connell, despite their frequent and bitter political differences, praised Cloncurry warmly: "In private society, in the bosom of his family, the model of virtue, in public life worthy of the admiration and affection of the people".

He was a good landlord, and worked hard to alleviate the suffering caused by the Great Hunger

The Great Famine ( ga, an Gorta Mór ), also known within Ireland as the Great Hunger or simply the Famine and outside Ireland as the Irish Potato Famine, was a period of starvation and disease in Ireland from 1845 to 1852 that constituted a h ...

. He had a keen interest in law reform, and as a magistrate

The term magistrate is used in a variety of systems of governments and laws to refer to a civilian officer who administers the law. In ancient Rome, a '' magistratus'' was one of the highest ranking government officers, and possessed both judici ...

began the practice of holding a court of petty session

Courts of petty session, established from around the 1730s, were local courts consisting of magistrates, held for each petty sessional division (usually based on the county divisions known as hundreds) in England, Wales, and Ireland. The sessio ...

, which was later established on a nationwide basis by the Petty Sessions (Ireland) Act 1851.

Writings

His memoir, published in 1849, claimed: "The independence of Ireland is sure to come at last – as sure as that the Roman Empire fell in pieces, or the North American provinces are now free states. When misfortune shall overtake England, or the lot common to empires as to individuals, can she lay the flattering unction to her soul that she has acted with probity towards Ireland?"References

Bibliography

* * * * Valentine Lawless,Personal recollections of the life and times, with extracts from the correspondence of Valentine Lord Cloncurry

', Dublin: J. McGlashan; London: W.S. Orr, 1849.

* Linebaugh, Peter; Rediker, Marcus,''The Many-Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners, and the Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic''. Boston: Beacon Press. (2000) . * * * ''Annals of Ardclough'' by

Eoghan Corry

Eoghan Corry ( ga, Eoghan Ó Cómhraí; born 19 January 1961) is an Irish journalist and author. He is the lead commentator on travel for media in Ireland, having edited travel sections in national newspapers and travel publications since the 19 ...

and Jim Tancred (2004).

{{DEFAULTSORT:Cloncurry, Valentine Lawless, 2nd Baron

1773 births

1853 deaths

Barons in the Peerage of Ireland

Members of the Privy Council of Ireland

United Irishmen

Prisoners in the Tower of London

Irish Anglicans

Protestant Irish nationalists

Peers of the United Kingdom created by William IV