Examples of verb second (V2)

The example sentences in (1) from German illustrate the V2 principle, which allows any constituent to occupy the first position as long as the second position is occupied by the finite verb. Sentences (1a) through to (1d) have the finite verb ''spielten'' 'played' in second position, with various constituents occupying the first position: in (1a) the subject is in first position; in (1b) the object is; in (1c) the temporal modifier is in first position; and in (1d) the locative modifier is in first position. Sentences (1e) and (1f) are ungrammatical because the finite verb no longer appears in the second position. (An asterisk (*) indicates that an example is grammatically unacceptable.) (1) (a) Die Kinder spielten vor der Schule im Park Fußball. The children played before school in the park Soccer (b) Fußball spielten die Kinder vor der Schule im Park. Soccer played the children before school in the park (c) Vor der Schule spielten die Kinder im Park Fußball. Before school played the children in the park soccer. (d) Im Park spielten die Kinder vor der Schule Fußball. In the park played the children before school soccer. (e) *Vor der Schule Fußball spielten die Kinder im Park. Before school soccer played the children in the park (f) *Fußball die Kinder spielten vor der Schule im Park. Soccer the children played before school in the park.Classical accounts of verb second (V2)

In major theoretical research on V2 properties, researchers discussed that verb-final orders found in German and Dutch embedded clauses suggest that there is an underlying SOV order with specific syntactic movements rules that changes the underlying SOV order to derive a surface form where the finite verb is in the second position of the clause. We first see a "verb preposing" rule which moves the finite verb to the left most position in sentence, then a "constituent preposing" rule which moves a constituent in front of the finite verb. Following these two rules will always result with the finite verb in second position. "I like the man" (a) Ich den Mann mag --> Underlying form in Modern German I the man like (b) mag ich den Mann --> Verb movement to left edge like I the man (c) den Mann mag ich --> Constituent moved to left edge the man like INon-finite verbs and embedded clauses

Non-finite verbs

The V2 principle regulates the position of finite verbs only; its influence on non-finite verbs (infinitives, participles, etc.) is indirect. Non-finite verbs in V2 languages appear in varying positions depending on the language. In German and Dutch, for instance, non-finite verbs appear after the object (if one is present) in clause final position in main clauses (OV order). Swedish and Icelandic, in contrast, position non-finite verbs after the finite verb but before the object (if one is present) (VO order). That is, V2 operates on only the finite verb.V2 in embedded clauses

(In the following examples, finite verb forms are in bold, non-finite verb forms are in ''italics'' and subjects are underlined.) Germanic languages vary in the application of V2 order in embedded clauses. They fall into three groups.V2 in Swedish, Danish, Norwegian, Faroese

In these languages, the word order of clauses is generally fixed in two patterns of conventionally numbered positions. Both end with positions for (5) non-finite verb forms, (6) objects, and (7), adverbials. In main clauses, the V2 constraint holds. The finite verb must be in position (2) and sentence adverbs in position (4). The latter include words with meanings such as 'not' and 'always'. The subject may be position (1), but when a topical expression occupies the position, the subject is in position (3). In embedded clauses, the V2 constraint is absent. After the conjunction, the subject must immediately follow; it cannot be replaced by a topical expression. Thus, the first four positions are in the fixed order (1) conjunction, (2) subject, (3) sentence adverb, (4) finite verb The position of the sentence adverbs is important to those theorists who see them as marking the start of a large(with multiple adverbials and multiple non-finite forms, in two varieties of the language) : Faroese

Unlike continental Scandinavian languages, the sentence adverb may either precede or follow the finite verb in embedded clauses. A (3a) slot is inserted here for the following sentence adverb alternative. :

V2 in German

In main clauses, the V2 constraint holds. As with other Germanic languages, the finite verb must be in the second position. However, any non-finite forms must be in final position. The subject may be in the first position, but when a topical expression occupies the position, the subject follows the finite verb. In embedded clauses, the V2 constraint does not hold. The finite verb form must be adjacent to any non-finite at the end of the clause. German grammarians traditionally divide sentences into fields. Subordinate clauses preceding the main clause are said to be in the first field (Vorfeld), clauses following the main clause in the final field (Nachfeld).The central field (Mittelfeld) contains most or all of a clause, and is bounded by left bracket (Linke Satzklammer) and right bracket (Rechte Satzklammer) positions. In main clauses, the initial element (subject or topical expression) is said to be located in the first field, the V2 finite verb form in the left bracket, and any non-finite verb forms in the right bracket.

In embedded clauses, the conjunction is said to be located in the left bracket, and the verb forms in the right bracket. In German embedded clauses, a finite verb form follows any non-finite forms. German :

V2 in Dutch and Afrikaans

V2 word order is used in main clauses, the finite verb must be in the second position. However, in subordinate clauses two word orders are possible for the verb clusters. Main clauses: Dutch : This analysis suggests a close parallel between the V2 finite form in main clauses and the conjunctions in embedded clauses. Each is seen as an introduction to its clause-type, a function which some modern scholars have equated with the notion of specifier. The analysis is supported in spoken Dutch by the placement ofV2 in Icelandic and Yiddish

These languages freely allow V2 order in embedded clauses. IcelandicTwo word-order patterns are largely similar to continental Scandinavian. However, in main clauses an extra slot is needed for when the front position is occupied by Það. In these clauses the subject follows any sentence adverbs. In embedded clauses, sentence adverbs follow the finite verb (an optional order in Faroese). : In more radical contrast with other Germanic languages, a third pattern exists for embedded clauses with the conjunction followed by the V2 order: front-finite verb-subject. : Yiddish

Unlike Standard German, Yiddish normally has verb forms before Objects (SVO order), and in embedded clauses has conjunction followed by V2 order. :

V2 in root clauses

One type of embedded clause with V2 following the conjunction is found throughout the Germanic languages, although it is more common in some than it is others. These are termed root clauses. They areItems other than the subject are allowed to appear in front position. : Swedish

Items other than the subject are occasionally allowed to appear in front position. Generally, the statement must be one with which the speaker agrees. : This order is not possible with a statement with which the speaker does not agree. : Norwegian

: German

Root clause V2 order is possible only when the conjunction dass is omitted. In such cases, formal usage also places the finite verb form into the present subjunctive (German ''Konjunktiv I'') if the verb form is clearly distinguishable from the indicative; if not, the past subjunctive (German ''Konjunktiv II'') is used. : By contrast, a form with an embedded first-person subject would usually use the past subjunctive here, since the present indicative and subjunctive appear identical: ''Er behauptet, ich hätte'' (instead of ''habe'') ''es zur Post gebracht.'' Compare the normal embed-clause order after dass :

Perspective effects on embedded V2

There are a limited number of V2 languages that can allow for embedded verb movement for a specific pragmatic effect similar to that of English. This is due to the perspective of the speaker. Languages such as German and Swedish have embedded verb second. The embedded verb second in these kinds of languages usually occur after 'bridge verbs'. (Bridge verbs are common verbs of speech and thoughts such as "say", "think", and "know", and the word "that" is not needed after these verbs. For example: I think he is coming.) Based on an assertion theory, the perspective of a speaker is reaffirmed in embedded V2 clauses. A speaker's sense of commitment to or responsibility for V2 in embedded clauses is greater than a non-V2 in embedded clause. This is the result of V2 characteristics. As shown in the examples below, there is a greater commitment to the truth in the embedded clause when V2 is in place.Variations of V2

Variations of V2 order such as V1 (verb-initial word order), V3 and V4 orders are widely attested in many Early Germanic and Medieval Romance languages. These variations are possible in the languages however it is severely restricted to specific contexts.V1 word order

V1 (V3 word order

V3 (verb-third word order) is a variation of V2 in which the finite verb is in third position with two constituents preceding it. In V3, like in V2 word order, the constituents preceding the finite verb are not categorically restricted, as the constituents can be a DP, a PP, a CP and so on.V2 and left edge filling trigger (LEFT)

V2 is fundamentally derived from a morphological obligatory exponence effect at sentence level. The left edge filling trigger (LEFT) effects are usually seen in classical V2 languages such as Germanic languages and Old Romance languages. The left edge filling trigger is independently active in morphology as EPP effects are found in word-internal levels. The obligatory exponence derives from absolute displacement, ergative displacement and ergative doubling in inflectional morphology. In addition, second position rules in clitic second languages demonstrate post-syntactic rules of LEFT movement. Using the language Breton as an example, absence of a pre-tense expletive will allow for the LEFT to occur to avoid tense-first. The LEFT movement is free from syntactic rules which is evidence for a post-syntactic phenomenon. With the LEFT movement, V2 word order can be obtained as seen in the example below. In this Breton example, the finite head is phonetically realized and agrees with the category of the preceding element. The pre-tense "Bez" is used in front of the finite verb to obtain the V2 word order. (finite verb "nevo" is bolded).Syntactic verb second

It is said that V2 patterns are a syntactic phenomenon and therefore have certain environments where it can and cannot be tolerated. Syntactically, V2 requires a left-peripheral head (usually C) with an occupied specifier and paired with raising the highest verb-auxiliary to that head. V2 is usually analyzed as the co-occurrence of these requirements, which can also be referred to as "triggers". The left-peripheral head, which is a requirement that causes the effect of V2, sets further requirements on a phrase XP that occupies the initial position, so that this phrase XP may always have specific featural characteristics.V2 in English

Modern English differs greatly in word order from other modern Germanic languages, but earlier English shared many similarities. For this reason, some scholars propose a description of Old English with V2 constraint as the norm. The history of English syntax is thus seen as a process of losing the constraint.Old English

In these examples, finite verb forms are in , non-finite verb forms are in and subjects are .Main clauses

Position of object

In examples ''b'', ''c'' and ''d'', theEffect of subject pronouns

When the subject of a clause was a personal pronoun, V2 did not always operate. However, V2 verb-subject inversion occurred without exception after a question word or the negative ne, and with few exceptions after þa even with pronominal subjects. Inversion of a subject pronoun also occurred regularly after a direct quotation.Embedded clauses

Embedded clauses with pronoun subjects were not subject to V2. Even with noun subjects, V2 inversion did not occur.Yes-no questions

In a similar clause pattern, the finite verb form of a yes-no question occupied the first positionMiddle English

Continuity

Early Middle English generally preserved V2 structure in clauses with nominal subjects. As in Old English, V2 inversion did not apply to clauses with pronoun subjects.Change

Late Middle English texts of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries show increasing incidence of clauses without the inversion associated with V2. Negative clauses were no longer formed with ne (or na) as the first element. Inversion in negative clauses was attributable to other causes.Vestiges in Modern English

As in earlier periods, Modern English normally has subject-verb order in declarative clauses and inverted verb-subject order in interrogative clauses. However these norms are observed irrespective of the number of clause elements preceding the verb.Classes of verbs in Modern English: auxiliary and lexical

Inversion in Old English sentences with a combination of two verbs could be described in terms of their finite and non-finite forms. The word which participated in inversion was the finite verb; the verb which retained its position relative to the object was the non-finite verb. In most types of Modern English clause, there are two verb forms, but the verbs are considered to belong to different syntactic classes. The verbs which participated in inversion have evolved to form a class ofQuestions

Like Yes/No questions, interrogative Wh- questions are regularly formed with inversion of subject and auxiliary. Present Simple and Past Simple questions are formed with the auxiliary do, a process known asWith topic adverbs and adverbial phrases

In certain patterns similar to Old and Middle English, inversion is possible. However, this is a matter of stylistic choice, unlike the constraint on interrogative clauses. negative or restrictive adverbial first : :::(see negative inversion) comparative adverb or adjective first : After the preceding classes of adverbial, only auxiliary verbs, not lexical verbs, participate in inversion locative or temporal adverb first : prepositional phrase first : :::(see locative inversion, directive inversion) After the two latter types of adverbial, only one-word lexical verb forms (Present Simple or Past Simple), not auxiliary verbs, participate in inversion, and only with noun-phrase subjects, not pronominal subjects.Direct quotations

When the object of a verb is a verbatim quotation, it may precede the verb, with a result similar to Old English V2. Such clauses are found in storytelling and in news reports. : :::(see quotative inversion)Declarative clauses without inversion

Corresponding to the above examples, the following clauses show the normal Modern English subject-verb order. Declarative equivalents : Equivalents without topic fronting :French

Modern French is a subject-verb-object (SVO) language like otherOld French

Similarly to Modern French,Old Occitan

A language that is compared to Old French isOther languages

Kotgarhi and Kochi

In his 1976 three-volume study of two languages ofIngush

In Ingush, "for main clauses, other than episode-initial and other all-new ones, verb-second order is most common. The verb, or the finite part of a compound verb or analytic tense form (i.e. the light verb or the auxiliary), follows the first word or phrase in the clause."O'odham

O'odham has relatively free V2 word order within clauses; for example, all of the following sentences mean "the boy brands the pig": ceoj ʼo g ko:jĭ ''ceposid'' ko:jĭ ʼo g ceoj ''ceposid'' ceoj ʼo ''ceposid'' g ko:jĭ ko:jĭ ʼo ''ceposid'' g ceoj ''ceposid'' ʼo g ceoj g ko:jĭ ''ceposid'' ʼo g ko:jĭ g ceoj The finite verb is "Sursilvan

Among dialects of the Romansh, V2 word order is limited to Sursilvan, the insertion of entire phrases between auxiliary verbs and participles occurs, as in 'Cun Mariano Tschuor ha Augustin Beeli ''discurriu'' ' ('Mariano Tschuor has spoken with Augustin Beeli'), as compared to Engadinese 'Cun Rudolf Gasser ha ''discurrü'' Gion Peider Mischol' ('Rudolf Gasser has spoken with Gion Peider Mischol'.) The constituent that is bounded by the auxiliary, ''ha'', and the participle, ''discurriu'', is known as a Satzklammer or 'verbal bracket'.Estonian

InWelsh

In Welsh, V2 word order is found in Middle Welsh, but not in Old and Modern Welsh which only has verb-initial order. Middle Welsh displays three characteristics of V2 grammar: (1) A finite verb in the C-domain (2) The constituent preceding the verb can be any constituent (often driven by pragmatic features). (3) Only one constituent preceding the verb in subject position As we can see in the examples of V2 in Welsh below, there is only one constituent preceding the finite verb, but any kind of constituent (such as a noun phrase NP, adverb phrase AP and preposition phrase PP) can occur in this position. Middle Welsh can also exhibit variations of V2 such as cases of V1 (verb-initial word order) and V3 orders. However, these variations are restricted to specific contexts such as in sentences that has impersonal verbs, imperatives, answers or direct responses to questions or commands and idiomatic sayings. It is also possible to have a preverbal particle preceding the verb in V2, however these kind of sentences are limited as well.Wymysorys

Wymysory is classified as a West-Germanic language, however it can exhibit various Slavonic characteristics. It is argued that Wymysorys enables its speaker to operate between two word order system that represent two forces driving the grammar of this language Germanic and Slavonic. The Germanic system is not as flexible and allows for V2 order to exist in it form while the Slavonic system is relatively free. Due to the rigid word order in the Germanic system, the placement of the verb is determines by syntactic rules in which V2 word order is commonly respected. Wymysory, like with other languages that exhibit V2 word order, the finite verb is in second position with a constituent of any category preceding the verb such as DP, PP, AP and so on.Classical Portuguese

Compared to other Romance languages, the V2 word order has existed in Classical Portuguese a lot longer. Although Classical Portuguese is a V2 language, V1 occurred more frequently and as a result of this, it is argued whether or not Classical Portuguese really is a V2-like language. However, Classical Portuguese is a relaxed V2 language, meaning V2 patterns coexist with its variations, which are V1 and/or V3. In the case of Classical Portuguese, there is a strong relationship between V1 and V2 due to V2 clauses being derived from V1 clauses. In languages, such as Classical Portuguese, where both V1 and V2 exist, both patterns depend on the movement of the verb to a high position of the CP layer, with the difference being whether or not a phrase is moved to a preverbal position. Although V1 occurred more frequently in Classical Portuguese, V2 is the more frequent order found in matrix clauses. Post-verbal subjects may also occupy a high position in the clause and can precede VP adverbs. In (1) and (2), we can see that the adverb 'bem' can precede or proceed the post-verbal subject. In (2), the post-verbal subject is understood as an informational focus, but the same cannot be said for (1) because the difference of the positions determine how the subject is interpreted.Structural analysis of V2

Various structural analyses of V2 have been developed, including within the model of dependency grammar and generative grammar.Structural analysis in dependency grammar

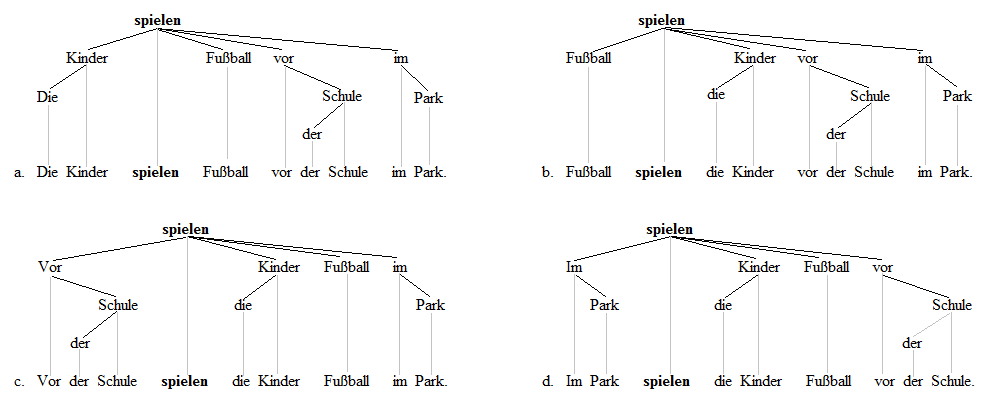

Dependency grammar (DG) can accommodate the V2 phenomenon simply by stipulating that one and only one constituent can be a predependent of the finite verb (i.e. a dependent which precedes its head) in declarative (matrix) clauses (in this, Dependency Grammar assumes only one clausal level and one position of the verb, instead of a distinction between a VP-internal and a higher clausal position of the verb as in Generative Grammar, cf. the next section). On this account, the V2 principle is violated if the finite verb has more than one predependent or no predependent at all. The following DG structures of the first four German sentences above illustrate the analysis (the sentence means 'The kids play soccer in the park before school'): :: The finite verb ''spielen'' is the root of all clause structure. The V2 principle requires that this root have a single predependent, which it does in each of the four sentences.

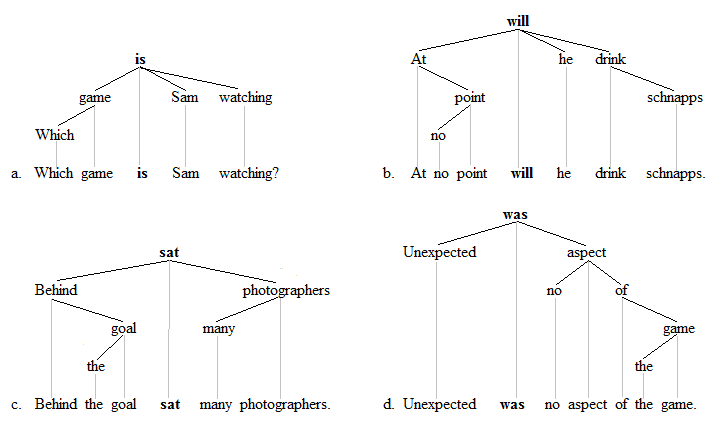

The four English sentences above involving the V2 phenomenon receive the following analyses:

::

The finite verb ''spielen'' is the root of all clause structure. The V2 principle requires that this root have a single predependent, which it does in each of the four sentences.

The four English sentences above involving the V2 phenomenon receive the following analyses:

::

Structural analysis in generative grammar

In the theory ofSee also

* Second position cliticsNotes

Literature

*Adger, D. 2003. Core syntax: A minimalist approach. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. *Ágel, V., L. Eichinger, H.-W. Eroms, P. Hellwig, H. Heringer, and H. Lobin (eds.) 2003/6. Dependency and valency: An international handbook of contemporary research. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. *Andrason, A. (2020). Verb second in Wymysorys. Oxford University Press. *Borsley, R. 1996. Modern phrase structure grammar. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers. *Carnie, A. 2007. Syntax: A generative introduction, 2nd edition. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. *Emonds, J. 1976. A transformational approach to English syntax: Root, structure-preserving, and local transformations. New York: Academic Press. *Fagan, S. M. B. 2009. German: A linguistic introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press *Fischer, O., A. van Kermenade, W. Koopman, and W. van der Wurff. 2000. The Syntax of Early English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. *Fromkin, V. et al. 2000. Linguistics: An introduction to linguistic theory. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers. *Harbert, Wayne. 2007. The Germanic Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. *Hook, P. E. 1976. Is Kashmiri an SVO Language? Indian Linguistics 37: 133–142. *Jouitteau, M. (2020). Verb second and the left edge filling trigger. Oxford University *Liver, Ricarda. 2009. Deutsche Einflüsse im Bündnerromanischen. In Elmentaler, Michael (Hrsg.) Deutsch und seine Nachbarn. Peter Lang. {{ISBN, 978-3-631-58885-7 *König, E. and J. van der Auwera (eds.). 1994. The Germanic Languages. London and New York: Routledge. *Liver, Ricarda. 2009. Deutsche Einflüsse im Bündnerromanischen. In Elmentaler, Michael (Hrsg.) Deutsch und seine Nachbarn. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. *Meelen, M. (2020). Reconstructing the rise of verb second in welsh. Oxford University Press. *Nichols, Johanna. 2011. Ingush Grammar. Berkeley: University of California Press. *Osborne T. 2005. Coherence: A dependency grammar analysis. SKY Journal of Linguistics 18, 223–286. *Ouhalla, J. 1994. Transformational grammar: From rules to principles and parameters. London: Edward Arnold. *Peters, P. 2013. The Cambridge Dictionary of English Grammar. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. *Posner, R. 1996. The Romance languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. *Rowlett, P. 2007. The Syntax of French. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. *van Riemsdijk, H. and E. Williams. 1986. Introduction to the theory of grammar. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. *Tesnière, L. 1959. Éleménts de syntaxe structurale. Paris: Klincksieck. *Thráinsson, H. 2007. The Syntax of Icelandic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. *Walkden, G. (2017). Language contact and V3 in germanic varieties new and old. ''The Journal of Comparative Germanic Linguistics, 20''(1), 49-81. *Woods, R. (2020). A different perspective on embedded verb second. Oxford University Press. *Woods, R., Wolfe, s., & UPSO eCollections. (2020). ''Rethinking verb second'' (First ed.). Oxford University Press. *Zwart, J-W. 2011. The Syntax of Dutch. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. * Linguistic typology Word order